'

\\K\\

DEWEY

i! 1 'O

-> 1 M!T LIBRARIES DUPLho

,DS-XG

3

9080 03317

5891

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

Do

Temporary

Help

Jobs

Improve

Labor

Market

Outcomes

for

Low

Skilled

Workers?

Evidence from

Random

Assignments

David

Alitor

Susan

N.

Houseman

Working

Paper

05-26

October

27,

2005

Revised:

March

17,2010

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

Thispapercanbe downloaded withoutchargefrom the SocialScience

Forthcoming:

American

Economic

Journal:Applied

Economics

Do

Temporary-Help

Jobs

Improve

Labor

Market

Outcomes

for Low-SkilledWorkers?

Evidence

from

'Work

First'Upjohn

InstituteWorking

Paper

05-124David Autor

MITandNBER

'e-mail:

dautor@mit.edu

Susan N.

Houseman

W.E.

Upjohn

InstituteforEmployment

Research

e-mail: housemanfSupiohninstitute.org

December

2008

Revised

August

2009

Abstract

Temporary-help

jobsofferrapid entry into paidemployment,

but theyare typicallybriefand

it isunknown

whetherthey foster longer-termemployment.

We

utilizethe uniquestructureofDetroit's

we

1fare-to-work

program

to identifythe effectof temporary-help jobson

labormarket

advancement. Exploiting therotationalassignmentofwelfareclientsto

numerous

nonprofit contractorswith differingjob placementrates,we

find thattemporary-help job placementsdo

notimprove

andmay

diminish subsequentearnings andemployment

outcomes

among

participants.In contrast,job placements withdirect-hire employers substantially raiseearnings and

employment

overaseven quarterfollow-up period.JEL:J24, J48, J62

Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

Member

Libraries

Temporary-help

firmsemploy

a disproportionate shareoflow-skilled and minorityU.S. workers(U.S.Department

ofLabor,Bureau

ofLabor

Statistics2005). Within thelow-wage

population,

employment

intemporary help isespeciallyprevalentamong

participants inpublicemployment

andtraining programs.Although

thetemporary-help industryaccounts for lessthan3 percentof averagedaily

employment

inthe UnitedStates, stateadministrative datashow

that15 to

40

percent of formerwelfarerecipientswho

obtainedemployment

intheyearsfollowingthe 1996U.S. welfarereform took jobs inthe temporary-helpsector.

1

Comparing

theindustrydistributionof

employment

ofparticipants inwelfare,jobtraining, and laborexchangeprograms

in Missouribefore and immediatelyfollowing

program

participation, Heinrich, Mueser,and Troske (2007) find that participation ingovernment programs

isassociatedwith a 50to 100percent increase in

employment

intemporary-helpfirms andthatno

other industry displayssucha spike in

employment.

The

concentration oflow-skilled workersinthetemporary-help sectorand thehigh incidenceof temporary-help

employment

among

participants ingovernment

employment programs have

catalyzed adebate as towhether temporary-helpjobs facilitateor hinder labor market

advancement.

Lack

ofemployment

stabilityisthe principalobstacletoeconomic

self-sufficiencyamong

the low-skilled population,andthus amain

goal of welfare-to-workandotheremployment programs

targeting low-skilledworkers istohelp participants find stableemployment (Bloom

etal. 2005).Temporary-help

jobsare typicallyless stablethan regular('direct-hire')jobs (King

and

Mueser

2005). Nevertheless,by

providingan opportunitytodevelopcontactswith potentialemployersand acquire othertypesof

human

capital,temporary-helpjobs

may

allowworkerstotransition tomore

stableemployment

than theyotherwisewould

have

attained. Moreover, because temporary-help firms facerelativelylow

screening andterminationcosts,

numerous

researchershave positedthatthese firmsmay

hire individualswho

otherwise

would

have difficultyfindinganyemployment,

and thatthismay

lead directly orindirectly to

employment

indirect-hire positions(Abraham

1988; KatzandKrueger

1999;Autor

2001

and

2003;Houseman

2001;Autor

andHouseman

2002;Houseman,

Kalleberg, and Erickcek 2003; Kalleberg, Reynolds, andMarsden

2003).See Autor andHouseman(2002) on Georgia andWashingtonstate;Cancianetal.(1999) on Wisconsin;Heinrich,Mueser,and Troske (2005) on NorthCarolinaandMissouri;and Pawasarat (1997) on Wisconsin.

Some

scholars and practitionershave

countered thattemporary-help firmsprimarily offer unstable and low-skilledjobs,which

providelittle opportunity forworkersto investinhuman

capitalorengage inproductivejobsearch (Parker 1994;Pawasarat 1997; Jorgensonand

Riemer

2000; Benner, Leete

and

Pastor, 2007). This argument,however, only impliesthattemporary-helpjobsinhibit labormarket

advancement

ifthesejobs displacemore

productiveemployment

activities; temporary-helpjobs

may

nevertheless increaseemployment

and earnings iftheysubstitute for spellsof

unemployment.

Thus, acentralquestion forevaluation iswhethertemporary-helppositions

on

averageaugment

ordisplace otherjob searchandhuman

capitalacquisition activities.

Because

itis inherentlydifficultto differentiatethe effects of holding given jobtypesfrom

theskillsand motivationsthatcause workerstoholdthesejobs initially, distinguishing

among

these

competing

hypotheses isan empirical challenge.This study exploits aunique aspectof

thecity ofDetroit'swelfare-to-work

program

(Work

First)to identifythe causaleffects oftemporary-helpand direct -hirejobs

on

thesubsequent labormarketadvancement of

low-skilled workers. WelfareparticipantsinDetroit areassignedon

arotating basis toone oftwo

orthreenot-for-profit

program

providers—

termedcontractors—

operating inthe districtwhere

theyreside. Contractors operating inagiven district havesubstantially different placementrates into

temporary-help and direct-hirejobsbutofferotherwise standardized services. Contractor assignments,

which

arefunctionally equivalenttorandom

assignments, are uncorrected withparticipant characteristics but,

due

todifferences incontractorplacementpractices, arecorrelatedwiththe probabilitythatparticipants areplaced intoadirect-hirejob, atemporary-helpjob, or

no

job duringtheir

Work

Firstspells.These program

features enableustouse contractorassignmentsas instrumental variables forjob-taking.

Our

analysisdraws on

administrative records fromthe DetroitWork

Firstprogram

linkedwith

Unemployment

Insurance (UI)wage

records fortheentire State ofMichigan

forover 37,000Work

First spellscommencing

between

1999and 2003.The

administrativedataprovideperson-level

demographic

informationon

Work

Firstparticipantsand thejobs they obtainduringtheir

Work

First spells.The

UI

wage

recordstrack participants' quarterlyearnings in eachjobheldfor

two

yearsbefore and afterentering theprogram. Consistentwith welfare populations studied inother states,the incidenceof temporary-helpemployment

in Detroit ishigh: one inample

variation to simultaneouslyanalyzethecausal effectsofdirect-hire and temporary-help jobson subsequent labormarket outcomes.The

analysisyieldstwo

main

insights. Placementsinto direct-hire jobssignificantlyimprove

subsequentearnings and

employment

outcomes.Over

aseven-quarterfollow-up period, direct-hireplacements inducedby

contractorassignmentsraiseparticipants' payroll earningsby$493

per quarter

—

approximatelya 50percent increaseover baselineforthis low-skillpopulation—

and increasetheprobability of

employment

per quarterby 15 percentage points—

abouta33percent increaseover baseline.

These

effectsare highly statistically significantand areeconomically large.

Temporary-help

placements,by

contrast, do not improve, andmay

evenharm, subsequent

employment

and earnings outcomes.The

precisionof ourestimatesrules outany moderately positive effectsof temporary-helpplacements. Thus, although

we

find thatjob

placements, overall, significantly

improve

affectedworkers' long-termemployment

and earningsoutcomes—

consistentwith resultsoflarge-scalerandom

assignmentstudies (seeBloom

etal.1997

andBloom

and Michalopoulos2001

for summaries)—

the benefitsof job placementservices derive entirely

from

placementsinto direct-hirejobs. This findingplaces an importantqualification

on

theconventionalwisdom

thatplacement into any job isbetterthanno

job.We

providea varietyoftests ofthe plausibilityand robustness oftheseresults.The

useof

contractorassignmentsas instrumental variables forjob placementtypes requiresthat either

contractors onlyaffectparticipant

outcomes

through theirinfluence on the typesofjobsthattheytakeor,alternatively,thatany othereffects thatcontractors

may

have on participantoutcomes

isorthogonaltotheeffectoperatingthrough job placement.

We

arguethat,by

design, contractorshave

little scope foraffectingparticipantoutcomes

otherthanthroughjob placementsand, forthe limitedsetofother servicesprovided, there is little variation

among

contractors. Consistentwiththisview,

we

demonstratethattheeffectofcontractorassignmentson

participantoutcomes

is fullycaptured

by

contractors' placementrates intotemporary-helpanddirect-hirejobs.We

alsodemonstratethatour findingsare robustto alternative specificationsofthe instrumental

variables, that ourresults

do

notsufferfrom

weak

instrumentsbiases, and thatourfindingscannot be ascribedto differences intheoccupational distributionof temporary-help and direct-hire jobs.

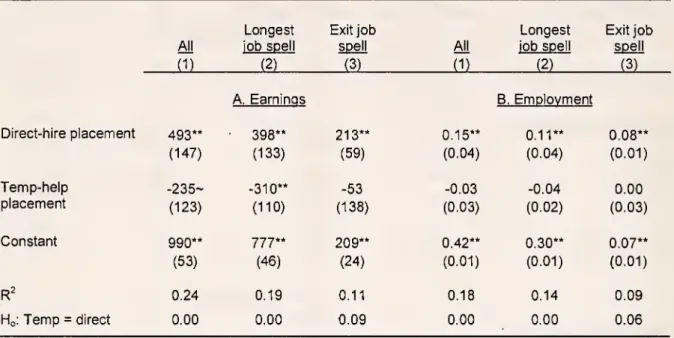

Complementary

analyses provide insights intowhy

direct-hire placements arefoundtoemployer-level datainthe

UI wage

records,we

find that thekey observabledifferencebetween

thesejob placements istheireffecton job stability.

Over

the seven-quarterfollow-upperiod, thebulk oftheearnings gain enjoyed

by

participantsplaced into direct-hirejobsderivesfrom

asingle, continuousjobspell. Direct-hire placementsgenerate durable earningseffectsinpart

becausetheplacement jobs themselveslast and inpartbecausetheplacement jobsserve as stepping stones into stablejobs. In contrast, placement jobsinthetemporary-helpsectorreduce job stability

by

allmeasures

we

areabletoexamine.Temporary-help

placementsincreasemultiplejob holdingand reducetenurein longest-heldjob, both indicators of jobchurn. Rather

than helping participants transition to direct-hirejobs, temporary-helpplacementsinitially leadto

more

employment

inthetemporary-help sector,which

servestocrowd

outdirect-hireemployment.

We

emphasizethatourfindingspertain to the marginaltemporary-help job placements inducedby

therandomization ofWork

Firstclientsacross contractors, and thereforedo

notprecludethe possibility thatinfra-marginal temporary-helpplacements generatesignificant

benefits.

However,

our findings address themost

pertinent policyissue:whether

increased (ordecreased) useof temporary-helpfirms injob placementoflow-skilledworkerswill

improve

participantoutcomes.

Our

study isthefirsttoexploita plausiblyexogenous

sourceofvariation intemporary-helpjob takingto

examine

the effectsof

temporary-helpemployment on

long-term labormarket

outcomes

among

low-wage

workers. Notably,ourconclusionsareatodds

with those ofseveralrecentU.S.and

European

studies that find thattemporary-helpemployment

provides a stepping stone into stableemployment.

2We

pointoutthatourOLS

estimatesare closelycomparable

tothoseintheliterature, implying any unique featureofour Detroit sample cannotexplain our

discrepant findings. Substantial differences

between

themarginaltreatmenteffects oftemporary-help placements recovered

by

our instrumental variables estimatesandthe averagetreatmenteffectsrecovered

by

estimatorsin other studiescould accountforthese disparatefindings.-U.S. studies includeFerberand Waldfogel(1998), Laneetal.(2003),Corcoran andChen(2004),Andersson,

HolzerandLane(2005, 2009), Heinrich,Mueser, and Troske(2005, 2007),and Benner, Leete andPastor (2007).

Studieson temporaryhelpemploymentinEuropeincludeBooth,Francesconi,and Frank(2002),Garcia-Perezand

Munoz-Bullon(2002),AnderssonandWadensjo(2004),Zijl,van denBerg, and

Hemya

(forthcoming), Ichino, Mealliand Nannicini(2005, 2008),Amuedo-Dorantes,Malo, andMunoz-Bullon(2008),BoheimandCardoso(2009),Kvasnicka(2009).Withtheexceptionof Benner, Leete andPastor (2007), these U.S.and Europeanstudies

uniformlyconcludethattemporary-help jobsbenefitworkers,eitherbyfacilitatinglonger-term labormarket

Alternatively, thestatistical techniquesused in previous studies

may

be unableto fullydifferentiatethecausal effectsofholding givenjobtypesfrom the

unmeasured

skillsandmotivationsthatcause self-selection intothesejobs.

1

Context:

Work

FirstContractor

Assignments

inDetroit

Our

study exploits theunique structureofDetroit'swelfare-to-workprogram

to identifythelong-term consequences of temporary-help and direct-hire

employment

on labormarketoutcomes

oflow-skilledworkers.Most

recipientsofTANF

benefits(Temporary

Assistance forNeedy

Families)must

fulfillmandatory

minimum

work

requirements.TANF

applicants inMichigan

who

do

not alreadymeet

thesework

requirements areassignedtoWork

Firstprograms,

which

serveto placethem

inemployment.

Foradministrative purposes, Detroit's welfare andWork

Firstprograms

are divided into fourteen geographicdistricts.TANF

participants are assignedtodistrictsaccordingto zipcode ofresidence.

The

city ofDetroitadministers the

Work

Firstprogram, buttheprovisionofservices iscontracted outto non-profit or public organizations.One

to threeWork

First contractors serviceeachdistrict,andwhen

multiple contractorsprovide

Work

First serviceswithin adistrict, thecity'sWork

Firstofficerotates theassignment ofparticipants to contractors.

The

contractortowhich

aparticipant isassigned thus

depends

on

thedatethat heor she applies forTANF.

The

Work

Firstprogram

is designedtoprovideshort-term, intensivejobplacement services.All contractors operating in Detroitoffera fairlystandardized

one-week

orientation,which

includes life-skillstraining. Following orientation,

few

resources are spenton anything butjob development, and, astheprogram

name

implies,the emphasisison

rapidplacement intojobs.Participants areexpectedtosearch for

work

on

a full-time basis. Besidesmonitoringparticipants'job searchefforts, contractors play adirect roleinjob placementby referring

participants toemployersor

by

hostingevents atwhich

employersrecruit participantsattheWork

Firstprogram

site.Although

participantsmay

findjobson theirown, most

contractors inourstudy reportedthatthey are directly involvedinhalf or

more

oftheirjob placements.Among

thosewho

are successfully placedinto ajob, three-fourthsareplaced within sixweeks of

program

entry. Virtually all participants areplaced into ajob orareterminated from theprogram

without aplacementwithin six

months

ofentry.3 Supportservices intended to aidjobretention,3

such as childcareand transportation, areequally availabletoparticipants inall contractors

and

are providedoutside theprogram

(AutorandHouseman

2006). Participantswho

do

notfindjobsduringtheir

Work

Firstassignments face possible sanctions. Consequently, unsuccessfulparticipantscontinuetohavestrong incentivesto

work

afterleavingWork

First.Figure 1 providesaschematic diagram ofDetroit's

Work

Firstprogram

andthe rotationalassignmentofparticipants to contractors.

Upon

entry,participants,who

vary interms oftheirpersonalcharacteristics and

work

histories, areassigned toacontractoroperating intheirdistrict.

4

Contractors playanintegral roleinhelpingto placeparticipants intojobs, but

systematicallyvary in theirpropensitiesto placeparticipants into direct-hire,temporary-help,or,

indeed, any jobat all.

It is logical toask

why

contractors' placementpractices vary.The

most

plausibleanswer

isthatcontractors areuncertainabout

which

type of job placement ismost

effectiveand hence pursue different policies. Contractorsdo

nothaveaccess toUI

wage

recordsdata(used inthisstudyto assessparticipants' labormarket outcomes), andtheycollect follow-updataonlyfora

shorttimeperiod andonly forindividuals placed injobs.Therefore, theycannotrigorously

assess whether job placements

improve

participantoutcomes

orwhetherspecificjob placementtypesmatter.

During

in-personandphone

interviewsconducted forthisstudy,contractorsexpressedconsiderable uncertainty,and differingopinions, aboutthe long-term consequences

of

temporary job placements (Autor and

Houseman

2006).2.

THE

RESEARCH

DESIGN

Centraltoourresearch design are

two

features oftheDetroitWork

Firstenvironment: (1)contractors operating inagiven districthave substantially differentplacementrates into

temporary-help

and

direct-hirejobsbut offerotherwise standardizedservices;and

(2)therotational assignmentofparticipants to contractors isfunctionallyequivalentto

random

assignments

—

aswe

show

immediatelybelow

—

sothatcontractorassignments areuncorrelatedwith participant characteristics.

Under

the plausibleassumption (explored indetail below) thatcontractors only systematicallyaffectparticipant

outcomes

inthepost-program periodthroughtheireffect on jobplacements,

we

canuse contractorassignmentsas instrumental variablestoParticipantsreentering thesystemforadditionalWorkFirstspellsfollow thesameassignment procedureandthusmaybe

studythecausal effectsof temporary-help anddirect-hireplacements

on

employment

andearnings of Welfarerecipients.

Our

analysisdraws

on aunique database containing administrative recordson

thejobsobtainedby participantswhile inthe

Work

Firstprogram

linkedto theirquarterly earningsfrom

the State of Michigan's

unemployment

insurancewage

records database.These

administrativedata

document

alljobsobtainedby

participants whileintheprogram

forallWork

First spellsinitiated

from

the fourth quarterof1999 throughthe firstquarter of2003

inDetroit.Work

Firstjob placements are classified as either direct-hireortemporary-help using acarefully

compiled

listofall temporary-helpagenciesinthemetropolitanarea.5The

Work

Firstdataarematched

tostatewide

Unemployment

Insurance datathatrecord totalearnings and industryofemployment

by

participant foreachemployer

foreachcalendarquarter.The UI

dataallowusto constructpre-and post-

Work

FirstUI

earnings foreach participant for the eight quartersbefore andafterthe quarterofprogram

entry.6

By

the secondquarter followingWork

Firstentry, virtuallyallparticipants have been eitherplaced intoajoborterminated from theprogram.

Thus

we

treatemployment

and earnings intheseseven quarters aspost-program outcomes, andwe

do

not includethefirstpost-entry quarter inouroutcome

data. Includingthisquarter haslittlesubstantiveeffect

on

ourresults, however, asshown

inanearlierworking

paperversionofthisstudy.7

Inthetime period studied, fourteendistricts in Detroit

were

servedby

two

ormore

Work

Firstcontractors, thus

making

thesedistrictspotentiallyusable forouranalysis. Intwo

districtswith large ethnic populations,theassignment ofparticipants to contractors

was

notdone on

arotatingbasisbutrather

was

based on languageneeds.We

drop thesetwo

districts from oursample.

We

further limit the sampleto spells initiatedwhen

participantswere between

theages of16 and 65 and dropspellswhere

reported pre- orpost-assignmentquarterlyUI

earnings5

Particularly helpfulwasacomprehensivelistof temporaryagencies operatinginourmetropolitan areaasof 2000, developed by

DavidFasenfestandHeidi Gottfried. Inasmallnumberofcaseswherethe appropriatecoding ofanemployerwasunclear,we

collected additional informationonthenatureofthe businessthrough aninternetsearch ortelephonecontact.

6

The UI wagerecordsexcludeearningsoffederalandstateemployees and oftheself-employed.

7

This paperisavailable http://web.mit.edu/dautor/www/ah-detroit-ianuary-2008.pdf.Amongthoseplacedintoajob99.6 percent

have beenplacedbythesecondquarter followingentry,andamongthoseterminatedwithoutaplacement97.6 percenthave been

officiallyterminatedbythesecondquarter,accordingtoWorkFirstadministrative records.Becausea highfractionof

participantswhounsuccessfullyexittheprograminquartertwoorsubsequentlyactuallyhaveUIearningsin firstquarter,it is

likely thatdefactotimeto exitamongparticipantsnotplacedintojobsisactuallyshorterthan indicatedintheadministrative

data.Participantswhoareplacedintojobsofficiallyremainintheprogramforuptothreemonths,andtheiremployersare

exceed $15,000 inasinglecalendarquarter.

These

restrictionsreducethe sampleby

lessthan 1percent. Finally,

we

drop all spells initiated ina calendar quarter in anydistrictwhere

one ormore

participating contractors receivedno

clientsduring the quarter, asoccasionallyoccurredwhen

contractorswere

terminatedandreplaced.Table 1

summarizes

themeans

ofvariableson

demographics,work

history, and earningsfollowing

program

entry forallWork

First participants inourprimarysampleaswell asby

placement

outcome

duringtheWork

First spell: direct-hireplacement,temporary-helpplacement, or

no

job placement.The

sample ispredominantly female (94 percent) and black (97percent). Slightlyunderhalf (48 percent) of

Work

Firstspells resulted injobplacements.Among

spells resulting injobs, 20 percenthave at leastone job with atemporary agency.Interestingly,

average

weekly

earningsaresomewhat

higherintemporaryhelpjobsthan indirect-hirejobsobtainedin

Work

First.The

bottom

panel of Table 1 reports averagequarterlyearningsandemployment

probabilityinquarters

two

througheight followingthequarter ofWork

First entry. Participants arecoded

asemployed

inaparticularquarteriftheyhaveanyUI

earnings during thatquarter.Average

employment

probabilityis definedas theaverage ofthoseemployment

dummy

variables overthe follow-upperiod.

The

averagequarterlyearnings andemployment

probabilitiesoverquarterstwo

toeight followingprogram

entryarecomparable forthose obtainingtemporaryagency

and

direct-hireplacementjobs, whileearnings and theprobabilityof

employment

forthosewho

do

not obtain

employment

during theWork

Firstspell are40

to 50 percent lower.The

averagecharacteristics ofparticipants varyconsiderably accordingtojob placement outcome.Compared

tothosewho

foundjobswhile inWork

First,thosewho

do

notfindjobs aremore

likely tohave dropped out of high school andto haveworked

fewerquartersand had lowerearnings before entering theprogram.

Among

thoseplaced injobs, thosetakingtemporary-help jobs actuallyhave

slightlyhigheraveragepriorearnings andemployment

than those takingdirect-hire jobs.

Not

surprisingly, thosewho

take temporary-help jobs while intheWork

Firstprogram

havehigherpriorearnings andmore

quartersworked

inthetemporary-helpsectorthanthose

who

take direct-hire jobs.9Thisfurtherreducedthe finalsample by3,091 spells,or 7.4 percent.

We

haveestimatedthemainmodelsincluding these observations with near-identicalresults.9

Ina small percentageofcases,employers' industrycodesaremissingintheUI wagerecords. Forthisreason, earningsand

Beforeturningto detailed testsoftheresearch design,

we

depict themain

resultsofanalysisin asetofscatter plots

comparing

averageUI

employment

andearningsoutcomes

forWork

Firstparticipants

by

contractorby

yearof assignmentagainstcontractor-year placementrates intotemporary-help and direct-hire jobs.

As

noted above, randomization ofWork

Firstparticipants tocontractors occurs within districtswithin aspecific

program

year.To

purgedistrict-yeareffectsfrom

these plots,we

first estimate person-levelOLS

regressionsof job placementtype obtainedduring

Work

First (direct-hire,temporary-help, orno

job) and post-programquarterlyUI

employment

and earningson

acomplete setofdistrictby

yearof

assignmentdummy

variables.We

calculatethecontractor-yearspecificcomponent

of eachvariable(temporary-helpplacement,direct-hire placement,

UI

earnings,UI employment)

asthemean

residual foreachregression

by

contractorand yearofassignment.By

purgingyearand districteffects, thisprocedure isolatesthe variation

on

which

ourresearch design relies:variationamong

contractors operatinginsame

district atthesame

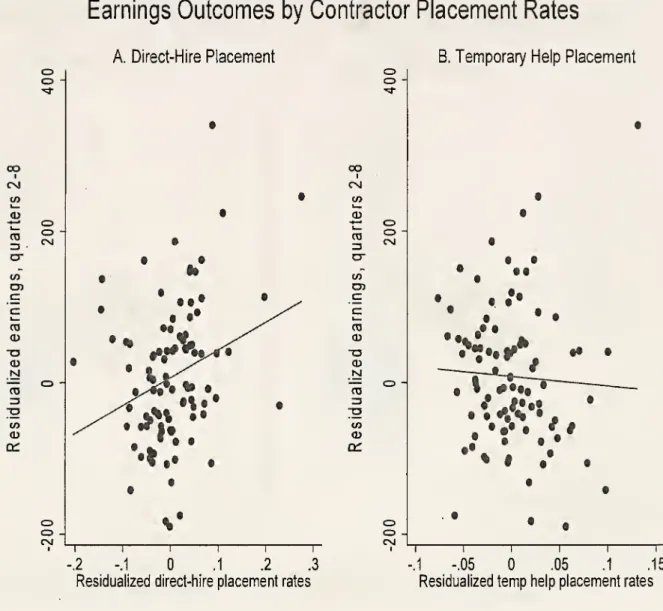

time.Figure 2aplotsparticipants' post-program quarterly

employment

probabilities—

defined asthe fraction ofquarters

two

through eightfollowing contractorassignmentinwhich

theyhave

positive earnings

—

againsttheircontractors' direct-hireplacement and temporary-help placementrates.10This figurerevealsthatparticipantsassignedto contractors withhigh direct-hire

placementrateshavesubstantiallyhigher average

employment

ratesinthepost-program period.There

isno similar relationship,however,between

contractors' temporary-help replacementratesand post-program

employment

probabilities oftheparticipants assignedtothem.An

analogousscatterplot forpost-programearnings over post-assignmentquarters

two

through eight (Figure2b) tellsasimilar story: participantsassignedto contractors with high direct-hire placementrates

have

substantially higher averagequarterly earningsin quarterstwo

through eightfollowingprogram

assignment, whilethe locusrelatingtemporary-helpplacement ratesand post-programearnings is essentially flat.

Our

subsequentanalysisteststhe validity ofthisresearch design andapplies it-—

withmany

refinements

—

to produceestimatesofthecausal effectsof job placementson

earningsandemployment

andto explorethe channelsthoughwhich

these causal effects arise.The

bottom lineof ouranalysis, however, is alreadyvisible inFigure 2.

'Inessence,Figure2

2.1

Testing

the

research

d.esignOur

research design requiresthatthe rotational assignmentofparticipants tocontractorseffectivelyrandomizesparticipants tocontractors operatingwithin each district in a given

program

year.We

testwhetherthedata areconsistentwithrandom

assignmentby

statisticallycomparing

the followingeight characteristicsofparticipants assignedtocontractors within eachdistrictand year: sex, whiterace,other (non-white)race, age and itssquare, average

employment

probability inthe eight quartersbefore

program

entry,averageemployment

probabilitywith atemporary

agency

intheseprioreightquarters,averagequarterly earnings in theseprioreightquarters,and averagequarterly earnings

from

temporaryagencies intheprioreightquarters.11In testingthe comparabilityofparticipants acrosseight characteristics,

we

are likely toobtainmany

false rejections ofthenull, andthis isexacerbatedby

the fact that participantcharacteristicsare notfullyindependent(e.g., participantswith highprior

employment

rates arealso likely to

have

high priorearnings).To

accountfortheseconfounding factors,we

estimate aSeemingly

Unrelated Regression (SUR),which

addresses both the multiplecomparisonsproblem

andthe correlationsamong

demographic

characteristicsacross participantsateachcontractor.' Thi's procedurecan bereadilydescribedwith a singleequation regression model:

XL=<*

+

r<+q>t+0

lt+*

t,+iDlat, (1)where

X

lcdlk isone

oftheeightmeasures used forthecomparison

(e.g., prioremployment,

gender, etc., all indexed

by

k) forparticipant i assignedtocontractor c serving assignmentdistrict

d

inyear t.The

vectors yand cp contain acomplete setofdummies

indicatingrandomization districtsand year-by-quarterofcontractorassignment, respectively,whilethe vector 6contains all

two-way

interactionsbetween

districtandyear.13Of

central interestin this equationisX, avectorofcontractor-by-yearof assignmentdummies,

with one contractor-by-yeardummy

dropped foreachdistrict-yearpair.The

p-valueforthe hypothesisthattheelementsof

X

are jointlyequal tozero provides anomnibus

testforBecause ofthe largenumberof missingvaluesfortheeducationmeasures,and becausesomecontractorswereapparentlymore

diligentthan othersaboutrecording participant education,weexcludeeducation variablesfromboth therandomizationtestand subsequentstatisticalanalysis.Regressionresultsthatinclude these variables(includingan "educationmissing"variable)are

nearlyidentical toourmainresults.

12

Thismethodfor testingrandomizationacrossmultipleoutcomesisproposed by Klingetal.(2004) and Kling,Liebman, and

Katz(2007).

Toconservedegreesof freedom,wedonot includedistrictbyyearbycalendar quarterinteractions. Modelsthatinclude these additionaldummyvariablesproducenear-identicalresultsandareavailablefromtheauthors.

the null hypothesisthatparticipantcovariatesdo notdiffersignificantly

among

participantsassignedto different contractorswithin adistrict-yearpair.

A

high p-value correspondstoan

acceptance ofthis null.

We

useSUR

toestimatethismodel

simultaneouslyforall eight covariatesinX

toaccountforthe correlationsamong

these variables. Ifwe

instead estimatedthis system equation-by-equation using

OLS,

we

would

obtain identical pointestimates but the standarderrorswould

be incorrect forthehypotheses ofinterest.The

resultsofthetests of randomizationare highly consistentwith a chancedistributionof

covariates.

The

top panel ofAppendix

Table 1 provides p-values forestimatesof Equation (1)appliedtothefull sample and fit separatelytoeach ofthe 41 district-by-yearcells.

The

overallp-valueforthe full sample pooled across districtsand yearsis 0.44.

Among

41 separatedistrict-by-yearcomparisons, 39 accept the nullhypothesisat the 10percentlevel orhigher, and only

one

comparisonrejectsthe null atconventional levelsofsignificance.

The

finalrow

andcolumn of

the table provide p-valuesforthe

comparison

test foreach year, poolingacrossdistricts,and

foreach district, poolingacross years. All butone ofthese sixteentestsreadily acceptsthe null at

conventionallevels ofsignificance.

These

results strongly support thehypothesisthat therotationalassignment ofparticipantsacross contractors generatesvariation thatcan betreatedas

random.

The

research design alsorequires thatrandom

assignmenttocontractors significantly affectsparticipantjob placements.

To

confirmthis,we

estimated asetofSUR

models

akinto equation(1)

where

thedependent variablesare participantWork

Firstjoboutcomes

(direct-hire,temporary-help, non-employment). Here,ourexpectation isthatjob placement

outcomes

shoulddiffersignificantly across contractors withina districtandyear. Testsofthishypothesisin the

panel

B

ofAppendix

Table 1 provide strong support fortheefficacy oftheresearch design: theomnibus

testforcross-contractor, within district-yeardifferences injobplacementoutcomes

rejects the nullat

below

the 1 percent level forthefull sample, asdo

16 of17tests for significantdifferences inplacementratesacross all districtswithin a year or within adistrictacross all

14

years.

We

alsocalculatepartialR-squaredvaluesfromasetofregressionsofjob placementtype (anyjob placement,direct-hirejob placement,temporary-help job placement) ondummyvariables indicatingcontractor-by-yearofassignmentafterfirstorthogonalizing thesejob placementtypeswithrespecttodemographic,earningshistory,and timevariables;conversely,we

computepartialR-squaredvaluesfromregressionsofjob placementtypeson demographic,earningshistory,and timevariables

afterfirstorthogonalizingthedependentvariablewithrespecttocontractorassignment.

We

find thatcontractorassignmentexplains 85to 130percentasmuchvariationinjobplacementtypeasdo demographic,earningshistory,and timevariables

3

Main

results:The

effectsof

jobplacements

on

earnings

and employment

We

usethe linked quarterly earnings records fromthestate of Michigan'sunemployment

insurancesystem to assess

how Work

Firstjob placementsaffect participants'earnings andemployment

overquarterstwo

through eightfollowingthecalendar quarterofrandom

assignmentto contractor.

Our

primaryempiricalmodel

is:Y

icdl=a

+

PA

+p

2T,+

X\k

+

yd+<p,+6

dl+

eicdl (2)where

thedependentvariableis average realquarterlyearnings or quarterlyemployment

(fromUI

records) definedoverthe follow-up period.Notationfordistrict,time, and district-by-yearvectors isthe

same

as in equation (1), withsubscripts i, c, d, and t referring,respectively,toparticipants,contractors, placement districts, andyear

by

quarterofparticipantassignment.The

binary variables £> and

T

:

indicatewhetherparticipant /obtained either a direct-hireor

temporary-helpjobplacementduring her

Work

First spell (with both equaltozero ifno

placement

was

obtained).To

accountforthegrouping ofparticipantswithin contractors,we

use Huber-White

robust standarderrors clusteredby

contractor (33 clusters).15Itbearsemphasisthatthere isnot amechanical linkage

between

job placements occurringduring the

Work

First spell and earningsandemployment outcomes

observed intheUI

datainthe follow-up period.

The

job placementvariableson

theright-hand sideofequation (2),D

and

T, refer tojobs obtained during the

Work

Firstspell andarecoded

usingwelfare case recordsfrom

the cityofDetroit.The

dependent variable,by

contrast, isobtained fromstate ofMichigan

unemployment

insurance recordsand measures labormarketoutcomes

inthe specified quartersfollowinfi

Work

Firstassignment.We

examine outcomes

beginning inthe second quarterfollowing

Work

Firstassignmentbecause, asnoted above, virtuallyallparticipants haveeitherbeenplaced intoajob or exited the

program by

thattime. It istherefore possible—

in fact,commonplace

—

foraparticipantwho

obtains ajob placement duringWork

Firsttohaveno

earnings inthe secondand subsequent quartersfollowing

program

entry and, conversely, foraparticipant

who

receivesno

placementto havepositive earnings inthe secondand subsequentpost-assignmentquarters.

' All

modelsalsoincludethevectorofeightpre-determinedcovariatesusedintherandomizationtest:sex,race (white, black,or

other),age andage-squared,andmeasures ofquartersofUIemploymentandrealUIearningsin direct-hireandin

temporary-helpemploymentinthe8quarters priortocontractor assignment.

We

suppress thesetermsheretosimplifytheexpositionoftheIn general,

we

would

notexpectequation (2)to recoverunbiased estimatesoftheeffectsof

job placements onparticipant

outcomes

when

estimated usingOrdinary LeastSquares.Only

abouthalfof

Work

Firstparticipants inoursampleobtainemployment

duringtheirWork

Firstspell (Table 1),and this setofparticipants is likely tobe

more

skilledand motivated towork

thanaverage participants. Unlesstheseattributesare fullycaptured

by

the covariatesinX,estimatesofP\ and/?2 are likely to bebiased.

We

addressthisbiasby

instrumentingD

andT

inequation(2) withcontractor-by-year-of-assignment

dummy

variables asoutlined in Section2.Our

useofcontractor-by-yeardummy

variablesas instruments isequivalenttousing contractor-by-year placementratesas instruments.To

facilitateexposition,we

can therefore rewriteequation (2) as,Y

icdl =a

+x

lD

cl+nj

c,+y

d+(p,+9dl+

va+

hcdl, (3 )where

D

cl isthe observeddirect-hire placementrateofcontractor c inyear t,T

cl isthecorrespondingplacementrate intemporary-help

employment,

andwe

omittheX

vectorfor simplicity.1

This equation underscoresthatour instruments enable the identification

of

the causal effectsof placements intodirect-hireand temporary-helpjobsthroughvariation injob placementratesamong

contractors thathavestatistically identical populations. Ingeneral, thesemodels

will yield estimatesofthe causaleffectsoftemporaryand direct-hirejob placementsforthe"marginal"placements

—

i.e.thosewhose

job placementtypewas

alteredby

contractor assignment. 7The

errorterm in equation(3) ispartitioned intotwo

additivecomponents, vcl

and

iicdl, tounderscorethe

two

keyconditionsthatouridentification strategyrequiresfor valid inference.The

first is thatunobservedparticipant-specific attributes that affectearnings (iidct)

must

beIfthevectorofparticipantcharacteristicswerealsoincluded,equation(3)woulddiffer slightlyfrom2SLSto thedegreethat

thereissamplecorrelationbetweencontractordummiesandparticipantcharacteristics(though inpractice, thiscorrelationis

insignificant, asshowninAppendixTable 1).Kling (2005) implementsan instrumental variables strategyanalogoustoequation

(3), inwhich meansoftheassignmentvariableareusedasinstruments rather than fixedeffects.

Inanextendedworking paperversionofthispaper(seelink infootnote7),weprovide a formal analysisofthe conditions

underwhichthecoefficientsfrom ourIVmodelsyieldcausaleffectsestimatesforindividualswhosejob placementwasaffected

bycontractor assignment.Iftheeffectof temporary anddirect-hireplacementsisconstantamongthesemarginalplacements

—

whatwetermlocallyconstanttreatmenteffects

—

ourIVmodelsyieldcausaleffectsestimatesfortheseindividuals.We

notethatanassumption oflocallyconstanttreatmenteffectsislessrestrictivethan thecommonassumptionofconstanttreatmenteffects fortheentiresamplepopulation. Alternatively,ifassignmenttoagiven contractoraffectstheprobabilitythatworkerstake

temporary-helpordirect-hirejobs(butnotboth),ourIVestimatesmaybe interpreted within theLocalAverageTreatment

EffectsframeworkofImbensandAngrist (1994).Intheextendedworkingpaper,weprovide empiricalevidencethatourIV

uncorrelatedwith

D

c!and

T

cl.The

evidenceabove

suggests thatthis condition ismet by

therotationalassignmentdesign.

The

second conditionisthatifthere isany

unobservedcontractor-by-yearheterogeneitythat affects participant

outcomes

butdoes not operatethrough job placementrates( vcl), itmust

bemean

independentofcontractor placementrates, i.e.,E(v

aD

cl)= E(v

clT

cl)-0.

This lattercondition highlightsthattheresearch designdoesnot requirethatcontractors only affectparticipant

outcomes

throughjobplacements.However,

it doesrequirethatany non-placementeffectsare uncorrelated with contractorjobplacementrates,

sincethis correlation

would

cause2SLS

estimatesto misattributetheeffects of unobservedcontractorpractices tojob placementrates.

As

outlined inthe Introduction, almostallWork

Firstresourcesare devotedtojobplacement, and

few

othersupport servicesareprovidedtoparticipants

beyond

the setofstandardized services offeredby

the cityofDetroittoallparticipants.Exploiting the factthat

we

havemore

instrumentsthanendogenous

right-hand sidevariables,

we

reportbelow

theresultsofoveridentificationtests,which

provide strongstatisticalevidenceofthevalidity ofthisassumption.

One

otherelementofthisspecification deserves note.Our

useofcontractor-by-yearof assignmentdummy

variables as instrumentsfortemporary-helpand direct-hirejob placements—

ratherthan simply contractorof assignmentdummies

—

allowsforan interactionbetween

contractorplacement

and

time period. This is usefulbecause even ifcontractors operating inadistrict

have

stable (but different) placementpolicies,thedifferences in temporary-helpand

direct-hireplacements

among

contractorsmay

varyover time in response tochanges inthe localeconomy

or changes intheaveragecharacteristicsofparticipants entering the program.18 InSection (4),

we

show

that estimatesofthe effectsof placementtype on earningsand

employment

outcomes

using contractor of assignmentas instruments are similar tothose obtainedusingcontractor-by-yearof assignmentas instruments.

18

For example,whentemporaryhelp positionsarescarce,observed percentagepointdifferencesamongcontractorsin

temporary-helpplacementratesarelikelytocontract.Surveyresults inAutorandHouseman(2006)also indicatethatsome

contractorshaveamendedtheirplacementpolicesinrecent years,withasignificantfractionreportinghaving reducedtheiruseof temporary-helpplacements.

3.1

Ordinary

least

squares

estimates

To

facilitatecomparison with prior studiesofthe impactof temporary-help anddirect-hirejobtaking

on

labor marketadvancement

ofwelfare participantsand otherlow-earningsworkers

(e.g.,Heinrich,

Mueser

and Troske 2005, 2007; Andersson, Holzer, andLane

2005,2007),we

begin ouranalysiswith ordinary leastsquares

(OLS)

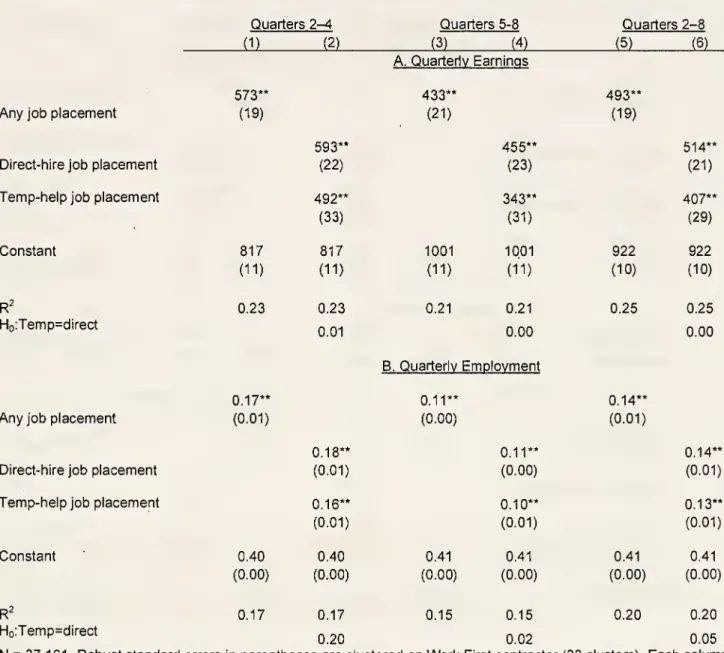

estimates ofequation(2). Table2presentsOLS

estimates foraveragereal quarterlyearnings and quarterlyemployment

forWork

Firstparticipants in quarters

two

through eight followingtheirassignmenttoWork

First contractorsusingall 37,161 spells inourdata.Forease ofinterpretation,

we

re-centerall control variablesby

subtracting the

mean

forparticipantswho

did notobtain ajob duringtheirWork

Firstspell.Thus,

by

construction,the interceptin equation (2) equalsthemean

oftheoutcome

variable forWork

First participantsnot placed into jobs.The

firstcolumn

ofTable 2shows

that, conditionalon detailedcontrols for race,ageand

prior

employment

and earnings,earnings inpost-assignmentquarterstwo

through fouramong

participants

who

obtained anyemployment

duringtheirWork

First spellwere on

average$573

more

per quarter than earnings for clientswho

did not obtainemployment

during theirWork

Firstspell.

Over

thatsame

horizon,theprobability ofemployment

was

17 percentage pointshigher per quarter

among

those placed intoajob during theirWork

Firstspellcompared

tothosewho

were

not.As

indicatedby

the interceptsofthese equations,averagequarterly earningswere

$817

andtheaverageprobability ofemployment

was

only40 percentamong

participantswho

did not obtain

employment

duringtheirWork

Firstspell.Column

(2) distinguishesoutcomes

for those takingtemporary-helpfrom

those taking direct-hirejobs during theirWork

First spells. Inquarterstwo

through fourfollowingWork

Firstassignmentparticipants

who

obtained atemporary-help positionduringtheirWork

First spellwere

slightly less likely to beemployed

and averaged $101 lessper quarterthanparticipantswho

obtained adirect-hire placement,though neitherdifference isstatisticallysignificant. Subsequent

columns

ofTable 2summarize outcomes

overlonger time horizons followingWork

Firstassignment. Participants

who

obtained ajob placement duringWork

First earnedan average of 53 percentmore

per quarter($493) and on averagewere

34 percentmore

likely to beemployed

(14percentage points) overthe entireseven-quarterfollow-up period

compared

to participantstemporary-help

and

direct-hirejobs duringWork

Firstcumulates slightlyoverthis longertimeframe,but issmall relative to the substantial gapin

employment

and

earningsbetween

thosewho

tookjobs during

Work

Firstand thosewho

did not.Over

the seven quarterperiod, earningsof

thoseplaced intotemporary-helpjobs

were

93 percentofearnings ofthoseplaced into direct-hirejobs, andthe earnings difference

between

thosewithatemporary-help versus adirect-hireplacement

was

just26

percentofthe earnings gapbetween

those with atemporary-help versusno

job placement.These

OLS

estimates are consistentwithotherpublished findings,most

notablywithHeinrich,

Mueser

and Troske (2005 and 2007).They

find thatMissouri and North Carolinawelfarerecipients

who

obtainedtemporary-help jobsin 1993 and 1997 earned almostasmuch

over thesubsequent

two

years as thosewho

obtaineddirect-hireemployment

—

and earnedmuch

more

than didnon

job-takers.Like Heinrich etal., ourprimaryempiricalmodels

forearningsand

employment

areestimatedforarelativelyhomogeneous

andgeographically concentrated populationand include detailedcontrols forobservableparticipantdemographic

characteristicsand prior earnings. Similartoourestimates, Heinrichetal.reportthatwelfareparticipants taking

temporary-help jobs earned atleast 85 percentofthat of workerstakingnon-temporary-help jobs overthesubsequent

two

years andthatthedollardecrement overthis periodto havingstarted inatemporaryhelp versus adirect-hirejob

was

lessthan onethird the positiveeffect ofatemporary job relative to

no

job.19

Though

less directly comparable, ourfindingsalsoechothoseof Andersson, Holzer and

Lane

(2005, 2007)who

report that low-skilledand low-earnings workerswho

obtaintemporary-help jobstypically fare relatively well inthe labormarket overthe subsequentthreeyears, despite startingwithlower earnings.

These

observationsprovideassurancethatoursamplefrom

the city ofDetroit iscomparable

to those usedinotherstudiesofjob-taking

among

welfarerecipients andother low-skilled workers.Moreover, the similaritybetween

ourOLS

estimates andthoseof Heinrich et al. forthe relationshipbetween

temporary-helpjob-taking and subsequentearnings suggeststhatthedifferences in causal estimatesthat

we

reportbelow

from instrumental variablemodels

aredue

tosubstantive differences inresearch designrather thantodifferences in sample frame. °

19

Henrich,Mueser and Troske (2005)pp. 165-166.

20

Tocontrolforpossible selection biasinthedecisiontotakeatemporaryagencyjob,Heinrichetal.estimate a selectionmodel

thatisidentifiedthroughtheexclusionofvarious county-specificmeasuresfromthemodelsforearnings but notfromthosefor

3.2

Instrumental

variables estimates

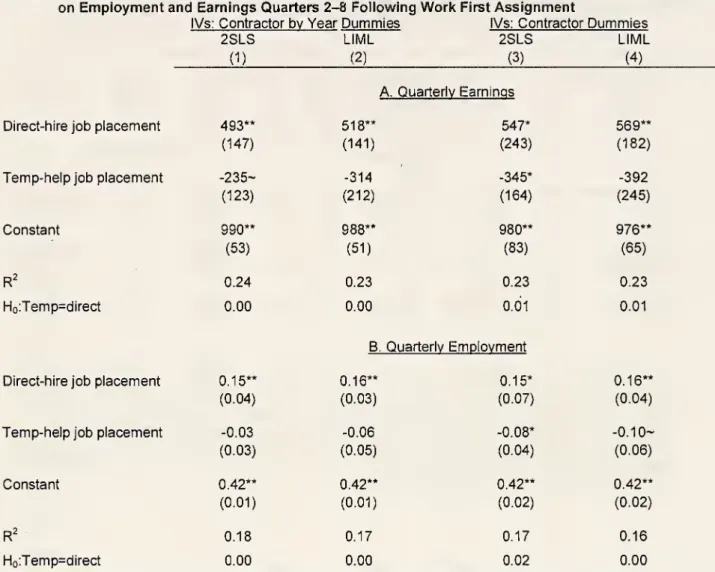

Table 3 reports instrumental variables estimatesofequation (2) forthe impactof

Work

Firstjob placements

on

subsequentemployment

and earnings,where

employment

placements duringthe

Work

First spell are instrumentedby

contractor-by-yearassignments.The

estimate incolumn

(1)confirms an economicallylarge and statisticallysignificant effectof

Work

Firstjob placementson

earningsandemployment

in quarterstwo

to fourfollowingWork

Firstassignment.Obtaining any job placement is estimatedto raisethe average

employment

probability inpost-assignmentquarters

two

tofourby

13 percentagepointsand increaseaveragequarterlyearnings

by

$301.These

effectsarehighly significant and aremore

than half thecorresponding

OLS

estimates (Table2).Column

2 distinguishesbetween

the causaleffectsof temporary-help placements andtheeffectsofdirect-hirejob placements.

These

estimates revealthatthe entirety ofthepositiveeffectof

Work

Firstjob placementsderivesfrom

placements intodirect-hirejobs. Direct-hireplacements induced

by

contractorassignmentraiseaverage quarterlyearningsby

$577 and

increasetheaveragequarterly

employment

probabilityby 20

percentagepoints inpost-assignmentquarters2through4. In

marked

contrast, thepoint estimateofthe effectof temporary-help placements onemployment

probability iscloseto zeroand insignificant, whiletheestimatedeffecton earnings isnegative (-$246 perquarter) and

weakly

significant.Subsequent

columns

of Table3show

that theemployment

andearnings effects ofdirect-hireplacementspersist into thesecond year following

Work

Firstassignment. In quarters5 through8, direct-hire placements induced

by

contractorassignmentsraise averagequarterly earningsby

$430 and

theemployment

probabilityby

11 percentagepoints.Over

the seven follow-upquarters, direct-hireplacements induced

by

contractorassignmentraisecumulative earningsby

anestimated $3,451, aneffectthatishighlysignificant and economicallylarge.

Conversely,the estimatedimpact ofatemporary-help placementon

employment

inquarterstwo

througheight is insignificantlydifferentfromzero, and the effecton quarterly earnings is earningsonlythroughtheirimpact onemploymentand jobtype,anassumptiontheyacknowledgeislikelyviolated. Thiscorrectionhaslittleeffectontheirregression estimates,suggestingeither thatthe selectionproblemisunimportantorthat their

instrumentsdonot effectively controlforselectionon unobservablevariables.

ThestandarderrorsinTable3donotaccountforpotential serialcorrelationinoutcomesamongparticipantswith multiple

spells.The37,161 WorkFirstspells inourdatacorrespondto24,903 uniqueparticipants,67percentofwhomhave onespell,22

percentofwhomhave2spells,and11percentofwhomhave3ormorespells.Toassess theimportanceofthisissue,we

re-estimatedmodelsfor totalearningsandquartersworkedovereightquartersusing onlythefirstWorkFirstspellper participant

observedinourdata.Thesefirst-spellestimates,availablefromthe authors,arecloselycomparabletoourmainestimatesfor

weakly

negative.The

95 percentconfidence intervalofthe estimatesexcludesearnings gainslargerthan $5 per quarterand increases intheprobability of

employment

ofgreaterthan 2percentagepoints. Inall cases,

we

reject the hypothesisthattheimpacts of temporary-helpand

direct-hireplacementseither on earnings oron

employment

are comparable.Figure3 providesfurther detail on theseresults

by

plotting pointestimatesand 95 confidenceintervals foranalogous

2SLS

estimatesofthe effectofdirect-hire and temporary-help jobplacements

on

earningsand

employment

probability in each oftheseven quartersin ourfollow-up period.

The

figureshows

thatdirect-hire placementssignificantly raiseboth earningsand

theprobabilityof

employment

inthefirstsixquartersand five quarters, respectively, ofthefollow-up

period.These

impacts begin todiminishafterthefifth quarter, consistentwithsome

fade-outofbenefits.22

By

contrast, estimatedimpacts of temporary-help placementson

employment

and

earnings generallyarenotsignificantly different

from

zero.While

this figuremakes

clearthatdirect-hirejob placements induced

by

Work

Firstcontractorassignments substantiallyincreaseearningsand

employment

ofWork

First clientsover thesubsequenttwo

years,we

findno

evidence, in contrast to prior research, that

comparable

benefitsaccruefrom

temporary-helpplacements.

One

noteworthypattern in theseresults isthatthedifferencebetween

theestimatedeffectsofdirect-hire and temporary-help placementson

employment

and earnings are largerinIV

than inOLS

models (compare

Tables2 and 3).Under

theassumptionthatthe effects of job placementtypeare

homogenous

acrossparticipants,this patternwould

suggestthatthose takingtemporary-help positionsare

more

positivelyselectedthan those takingdirect-hirejobs,which

iscounterintuitive and appears inconsistentwith the patternsfound in our

OLS

models

reported inTable 2. 23

Tempering

this interpretation isthe fact thattheIV models

identifythe effectof jobplacementson marginal workers, i.e., those

whose

job placementsarecausally affectedby

Theevidencesuggestingthatthebenefitsofjob placementsfade withtimeechoesthat inCard and Hyslop (2005)whofind, in

thecontextofaCanadianwelfareprogram,thatinitialjobaccessionsinducedbya time-limited earnings subsidy tendtopeak

afterapproximately 15monthsand,inthelimit,donotproducepermanentearningsgains.Nevertheless,fromapolicy perspective, ajob placementthatraisesearningsandemploymentfortwofullyearsmaystillbe viewedassuccessful.

23

TheOLSestimatesinTable2comparemeanearningsandemploymentofparticipantswhofounddirect-hireor

temporary-help jobs during theWorkFirstspellrelative toparticipantswhofound noemploymentduring thespell.Workersself-selecting

into direct-hirejobs obtain significantly higherpost-programearningsandemploymentthanworkersself-selecting into

temporary-helpjobs,and bothobtainhigher earningsandemploymentthan thosewithnoWorkFirstjob.This patternaccords

with the standardintuition thatworkers foundintemporary-help jobsare lesspositivelyselectedthanworkersfoundin direct-hirejobs.

contractorassignments. Ifthe effects of job placementtype are heterogeneous

between

marginal and inframarginalworkers,IV models

arenot necessarily informativeaboutthe directionof

biasin

OLS

estimates.24 It isplausiblethatthesemarginalworkers,on

average, differfrom thosewhose

placement job is unaffected by contractorassignment and experiencedifferenttreatmenteffects.

Why

might marginal direct-hireplacementshave

such great benefit, whiletemporary-helpplacementshave so little?

Work

First participants differinthe degreetowhich

theyrelyon

employer

contactsprovidedby

the contractorto findjobs.Many

participants findjobson theirown,

drawingupon employer

contactsfrom priorwork

experience orfrom family and friends.Those

who

aremost

reliant on contractor input, however, are likely to haverelativelyfew

personal contactsand less wherewithalto find

good

jobs ontheirown.

The

job placementsobtained

by

theseworkers aremost

likely to becausally affectedby

theircontractorassignments. Arguably, theseare alsothe workerswho

standtobenefitmost from

obtainingplacement intoastablejob.Thus, themarginalbenefit ofadirect-hireplacement

may

berelatively highandthemarginal benefit

of

atemporary-helpplacementmay

berelativelylow

fortheseparticipants.Indeed,the resultsinTable 3 implythat direct-hirejobs are scarce; marginal participantsplaced

in direct-hirejobs

on

averagewould

nothave

obtainedjobsthatwere

equallydurable orremunerative hadthey not received these placements. Conversely,the

IV

results suggestthatmarginal workers placed intemporary-help positions

would on

average havefared equally well, orsomewhat

better, withoutsuch placements. Consistentwiththisinterpretation,we

show

inSection 5 thatmarginal temporary-help placements raiseearnings in temporaryhelp positions but

crowd

out earnings in direct-hire positionsat agreaterthan one-to-onerate,thus loweringearnings in net.

24

Toseethis,consider a casewhereself-selection intobothtemporary-helpanddirect-hireemploymentisfunctionally equivalenttorandom assignment, soOLSestimates recover themeancausaleffects forbothtypesof job placementsforthose

whogainemployment. Thismeaneffectmayincludeamixtureofpositive,negativeandzeroeffects,thoughtheweighted averageoftheseeffectsisassumedtobepositive.Eveninthisscenario,thecausaleffectof temporary-helpemploymentforthe

marginal temporary-help jobtakermaybenegative.Thiswouldbe the caseifthecompilerstotheassignmentmechanism

4

Testing the

identificationframework

This section explores

two

central aspectsofthe identification framework.We

firstconsiderthe validityofusing contractor

random

assignmentsasinstrumental variables forWork

Firstparticipants' placementintotemporary-helpand direct-hirejobs.

Next

we

testthe robustnessof

the instrumental variablesresults to plausiblealternative specificationsoftheinstruments.25

4.1

Validity

of

the

instruments

Our

identification strategy restson

theassumptionthatcontractorassignments arevalidinstrumental variables for

Work

First participants'employment

intemporary-help anddirect-hirejobs. Validity requires

two

conditions: (1) contractorscausallyaffectthe probabilitythatWork

Firstparticipantsobtain direct-hireand temporary-helpjobs, acondition directlyverified in

Section 2.1; and (2)contractorsonly systematically affect

Work

Firstparticipants'employment

outcomes

in quarterstwo

througheight followingWork

Firstassignment through placementsintodirect-hire and temporary-help jobs during the

Work

Firstspell. If this latter (exclusion)condition

were

violated—

thatis, contractors affected participantoutcomes

through channelsotherthantemporary-help ordirect-hirejob placements

—

and theseother contractor impactswere

correlatedwith job placementrates—

ourinstrumental variableswould

becorrelatedwith' the errortermsof our

2SLS

models

and theestimateswould

bebiased.While

the restriction thatcontractors only systematicallyaffectparticipantoutcomes

throughjob placementsis fundamentallyuntestable,

we

can directly evaluate theimportanceofheterogeneity in contractoreffects

on

participantoutcomes by

takingadvantageofthe factthatwe

have 59 instruments (contractor-by-yeardummy

variables)and onlytwo endogenous

variables (temporary-help anddirect-hire placements).26This permits ustouse an

overidentificationtestto assesswhether asaturated

model

using59 contractor-by-yeardummies

25

In onlineAppendixTable A,wealsoexaminewhetherthelargedifferencesin theconsequences of temporary-helpand direct-hirejob placementsare attributable todifferences thetypesofpositionsobtainedintemporary-helpversusdirect-hire

employmentratherthantodifferencesintheemploymentarrangementsperse. Productionjobsareheavilyoverrepresentedin

temporary-helpplacements. Using ourIV frameworktoestimate fourendogenousvariables(temporary-help placementsin

production and nonproductionjobsanddirect-hireplacementsinproductionand nonproductionjobs)weshowthatourresultsare

notattributable tooccupational differencesintemporary-helpanddirect-hirejobs. Direct-hireplacementsintobothproduction and nonproductionjobs significantlyimprove subsequentemploymentandearnings,whiletemporary-helpplacementsintoboth productionandnonproduction jobs donotimproveand,inthecaseof productionjobs,mayharmsubsequentearningsand

employmentoutcomes.

26

Thereare 100contractor-by-yearcellsand40district-by-yeardummyvariables plusanintercept.Thisleaves59

as distinct instrumental variablesforparticipant

outcomes

is statistically equivalentto afarmore

restrictive parameterization in

which

contractoreffectson participantoutcomes

operateexclusivelythrough direct-hireand temporary-helpplacements.

The

overidentificationtest revealsacompellingresult:we

detectno statisticallysignificanteffect

of

contractorassignmenton participantoutcomes

that isnotcapturedby

temporary-helpand direct-hireplacements. In otherwords, the dataacceptthe null hypothesisthatthe59

contractor-by-year

dummy

variableshave

no

significant explanatorypower

for participantoutcomes

beyond

theireffectson

temporary-helpand direct-hirejobplacements.This resultholds forthe fullseven quarter

outcome

period and forboth sub-periods, as isvisible inthebottom

row

of each panel of Table 3. Forearnings outcomes,the p-valuesoftheoveridentification testsrange from 0.36to 0.42. Forquarterly

employment

outcomes,the p-values rangefrom

0.09 to0.21 (seethebottomrow

of eachpanel of Table3).It iswidely recognized thatoveridentification tests

may

havelow

power

against thenull (cf.Angristand Pischke, section4.2.2). Thatisnot the casehere, however. If

we

insteadcompare

theunrestricted

model

2SLS

model

(i.e., with 59dummies)

against a parameterizationthatcollapsestemporary-help and direct-hireplacements into asingle

employment

category(thus reducing 59 parameterstoone ratherthan two), the overidentificationtestrejectsthe null atthe2 percentlevel forsevenquarter

employment

and acceptsitatthe20

percent level forseven quarterearnings

(down from

36 percent). Thus, a parameterizationthatdistinguishesbetween

thecausaleffects

of

temporary-helpand

direct-hireplacements isboth necessary and sufficient tostatistically capture thefull effectofcontractorassignments

on

participantoutcomes.These

resultsdemonstratethatany setofcontractorpractices thatsystematically affectparticipant

outcomes

butdoes notoperatethrough job placementswould

haveto be collinearwith

—

and hence statisticallyindistinguishablefrom

—

contractorjobplacements.We

view

thispossibility as unlikely.

Based

on adetailed surveyofWork

Firstcontractors in theDetroit areaanalyzed bythis study(Autorand

Houseman

2006),we

document

thatprogram

funding istightand

few

resourcesare spenton

anything butjob placement.A

standardizedprogram

ofgeneral orlife skillstraining isprovided in thefirst

week

oftheprogram

by all contractors. Afterthefirstweek,

all contractors focuson

job placement. Supportservices intended toaidjob retention, suchaschildcare andtransportation, areequally availabletoparticipants from all contractors

and

areaffectparticipant

outcomes

other'thanthrough jobplacements, andwhat

other servicesdo

exist are fairlyuniformacrosscontractors;thustheirprovision shouldbe uncorrelatedwith contractorjob placements.

Adding

tothisbody

ofevidence,we

findinthe Detroitdatathatdirect-hireandtemporary-helpjob placementratesarepositively andsignificantly correlatedacross contractors, implying

thatcontractors withdirect-hireplacementratestendto

have

hightemporary-help placementrates. This factreducesthe plausibilityofascenario in

which

anothersetofcontractorpractices,collinearwithjobplacements, accountsforour

IV

estimatesshowing

divergenteffectsofdirect-hireand temporary-help job placement.27

4.2

Robustness

and power

of

the

instruments

The

2SLS

models

inTable 3 use contractor-by-yearof assignmentdummy

variables asinstrumentsfortemporary-help

and

direct-hirejobplacements.These

instrumentsallow fordifferences in placementrates

among

contractors operating in aparticulardistricttochange

over time due to,forexample, changes inthe localeconomy,

changes in averageparticipantcharacteristics, orchanges inplacementpolicies

by

individual contractors.Although

allowingfor

some

interactionbetween

contractordummy

variables and timeisefficient, asarobustnesscheck

on

our parameterizationofthe instrumental variables,we

reportin Table 4 estimatesfor themain

empiricalmodel

inwhich

we

use as instruments contractorassignmentsratherthan contractor-by-yearassignments.We

alsorepeat the baselinemodels

incolumn

(1) forreference.Point estimates

from

thesecontractor-only2SLS

models

found incolumn

(3) prove quitecomparable

tothebaselineestimates.Although

standard errorsare slightly larger, asexpected,these

models

clearly affirm thepriorconclusions: direct-hireplacements significantly raiseemployment

andearnings; direct-hire effectsare significantly largerthan thecorrespondingeffects fortemporary-help placements;theeffectsof temporary-help placements

on

employment

27

In theonlineworking paperversionofthisarticle,weshowinAppendixTable3thatifseparate2SLSmodelsfor thecausal

effectsof temporary-help anddirect-hirejob placementsareestimatedusing thefullsetofcontractor-by-year instrumentsineach model,theresultingpointestimatescontinuetoindicatethatdirect-hireplacements havelargepositiveimpactsonearningsand

employment(comparabletothemainmodelsinTable3)whiletemporary-helpplacementshavesmallandinsignificanteffects

onthesemargins.Giventhe significant positivecorrelationbetween temporary-help anddirect-hireplacementrates,theseresults

suggestthat'bad contractors' cannotberesponsibleforthelackofbeneficialimpactsof temporary-helpjob placementson

participantoutcomes;ifbadcontractorswereresponsible,theseadverseeffectsshouldloadontobothdirect-hireand

temporary-help point estimatesintheseby-placement-typemodelsgiven the positive correlationbetweendirect-hireand temporary-help placementrates.