On The Iconic Difference between Couple Characters in Boys Love Manga Febriani Sihombing

Abstract: Boys Love offers the romantic narratives between two male characters, which read by mostly women. Despite the foundation of relationship between the characters is based on that of heterosexual, the physiques of the characters do not represent those of individually man or women. This paper relates and explores the iconic difference between the two characters and relates it the capability of difference to represent BL text.

Keywords: BL / manga / bishōnen

The contemporary manga industry has grown in diversity, as can be seen by the existence of manga magazines and compilations covering specific themes targeted at specific audiences. This genre diversification was impossible to find in the time before World War I, when genre categories did not yet exist within manga1. One of the genres that now holds a share of roughly 11.9 billion yen (US$144.5 million) (Sugiura 2006, 27) in the industry covers the theme of romantic relationships between two male characters, known as Boys Love (BL)2. The storytelling and the visual narratives of this genre are similar to and often overlap with those of shōjo manga, from which BL developed as a sub-genre (Yamamoto 2005, 12). This is probably the main reason of why it is mostly read by heterosexual females (Nagakubo 2005; Kaneda 2007) instead by the gay community.

In the BL genre, the main characters fall into two categories – seme and uke – according to their roles in sexual intercourse. The terms of seme and uke are solely used in the circle of the BL franchise; in which the seme character inserts his penis and the uke character uses his anus to attain sexual pleasure. Seme and uke strictly do not switch sexual roles in the majority of BL text (Yamamoto 2005, 19) as their physical relationship is modeled on heterosexual relationships (Hori 2009; Mizoguchi 2000; Nagakubo 2005). Thus, seme and uke can be compared to both the male and female in a heterosexual relationship.

The combination of seme and uke plays an importance in the genre. This combination is termed ‘coupling’ (kappuringu) or ‘pairing’ and ‘shipping’ in the Western part

of the world, and stated by the symbol “×” in Japan or “x” and also “/” in the West. Summaries on BL commodities frequently state the sexual roles of the characters through a simple “(seme character)×(uke character)” statement on the product information. The use of this statement to represent this product relies on the universal expectations of the representation of the combination of seme and uke characters to represent BL story and as well as the taste of its readers. (Fujimoto 2007; Kaneda 2007; Hori 2009).

Visualization of the characters is similarly powerful in providing information on sexual roles for the characters. The information is encoded within the paired character images; which explains why readers can distinguish between the seme and uke from illustrations on the packages of BL products. In the case of BL manga, the majority of readers also have a general idea of the sexual roles of the characters by seeing manga covers and processing encoded information as they continue reading until the final confirmation of an explicit or non-explicit sexual intercourse scene. Determining the iconic codes of the drawn image of seme and uke will be the focus of this paper.

Discovering such codes in BL is made difficult due to the fact that even though seme and uke characters are metaphorical representations of the male and female in a heterosexual relationship, there is no binary adaptation of overtly masculine and feminine images in BL. Instead, the majority of main characters are an embodiment of both male and female features, but representing neither. This type of male character is called bishōnen.

Bishōnen characters in BL, as in shōjo manga, have unique physiques, especially when compared to the typically well-muscled male leads in American comics. The bishōnen phenomenon can be tracked back to the 1970s, when BL was known as shōnen ai. The subject of male homosexual relationships made its debut to the manga world through works from a group of female writers such as Keiko Takemiya and Moto Hagio, which depicted romances between adolescent boys with big and long eyelashes, with androgynous looks and figures as seen in Fig. 13. The term itself means ‘pretty boys’. In the recent years, bishōnen is not exclusively associated with adolescent boys, but generally male characters with good-looking, androgynous features4. The figure of pretty male characters eventually assumed more masculine features although traits such as bulging muscles remained scarce as they are

considered an extreme depiction of masculinity that is undesirable in bishōnen (Nakajima 1987, 91). This nature of bishōnen influenced the assessments of BL in the context of academic research and social criticism.

The phenomenon of BL as a male-homosexual text but written and read by mostly heterosexual females piqued the interests of researchers who largely employed it as a case study of social and gender studies. One of the most popular theories to answer the question of why girls love BL is escapism. Sociologist Chizuko Ueno argued that females can experience the freedom and ambition they are prohibited from by relating themselves to the “boy” in the BL text (Ueno 1998, 127). The identification of female readers with a boy character is made possible because of the androgynous nature of bishōnen, which Ueno calls the ‘idealized personification of self’ (females) (ibid, 131). Another notion on the subject was also made by author Azusa Nakajima, stating that girls can escape their sexual inferiority by associating themselves with the uke in BL (Nakajima 2005, 323–324). This theory sounded more reasonable to the public, especially remembering that this theory was proposed by Nakajima, who was also active as a BL novelist under the pseudonym of Kaoru Kurimoto5.

However, opinions towards this genre have changed and BL is in dire need for researchers to study it as a text instead of a superficial reflection of mentality of its authors and readers. First, there is now greater diversity in readership motivations. While BL is still regarded by some as a ‘massage space’ free from forms of oppression unique to individual readers (Fujimoto 2007, 42), BL as a sub-culture (Ueno 2007, 36), is also enjoyed as a form of entertainment as opposed to escapism from social insecurities (Kaneda 2007, 13). There are

also differences in the emotional identification of readers. Female readers cannot be generalized as identifying with the uke as the one fulfilling female sexual roles; readers can empathize with either the seme or uke (Mizoguchi 2000; Yoshinaga 2007), to both the seme and uke (Nagakubo 2005, 259), or to neither and instead enjoy the third party voyeuristic view (Mizoguchi ibid.; Yoshinaga ibid.). Hence, it is impossible to reach a general consensus on the BL reading phenomenon, given that BL works have expanded diversely and taking into account the tastes of readers.

Despite the diversity in BL readership and opinions, and the primarily bishōnen appearance of both the seme and uke, the uke is generally depicted in a more feminine manner. Uke can be associated in such way because of the presence of the seme. By presenting both characters together in any form of text, readers can recognize the more masculine or feminine of the paired characters. This is one reason why representation of the pairing is specifically important; it puts them in a state where they can be compared and contrasted to each other. This way, the comparison shows the contrasting traits of seme and uke while maintaining their character diversity but with the same gender identity. (Nagakubo 2005, 100).

Literature researcher Yōko Nagakubo in Yaoi Shōsetsuron (Discourse of Yaoi Novel) proposed the topic of comparison in the context of BL novels, which arose from emphasizing encoded male and female gender codes from respectively seme and uke. For example, a “cool and charismatic basketball club captain” can be the seme character for a “cute, short, but beautiful freshman” uke. Similarly, “beautiful voice” for seme and “normal boy” for uke can act as codes that suppress over-masculinity for seme and over-femininity for uke.

On the other hand, essayist Yumiko Watanabe states that the differentiation ensues from a hierarchical or any similar power-based relationship between seme and uke (Watanabe 2007, 71). In her opinion, a seme should be the one showing dominance over his counterpart. For example, in the summary of Akira Norikazu’s manga Heart♥ Strings (2007) written below:

A real man with a dangerous scent – yakuza top member Sakaki (Seme) vs charismatic masculine club host Yuki (Uke)! Unexpected events lead Sakaki to be Yuki’s patron in the club he’s working for. How will Yuki deal with the situation, after knowing that Sakaki’s sweet kisses are “just for fun”!? (my translation)

The sexual roles of the characters in the text above are apparent even if the intentional use of the terms seme and uke was omitted. The words to describe Sakaki – real man, dangerous, yakuza top member, a patron for the other character – proved that he is more masculine and dominant from Yuki, whom although not depicted with any feminine codes is proved uke by the circumstances of the text.

Information on sexual roles obtained through comparison can also be seen in simple pairing combinations, such as in SASRA (2007), a young adult novel series by Unit Vanilla, which advertises the premise of their stories as simply “Spain Invader × Beautiful Incan Noble” or “Strongest German Fighter × Roman General.” Despite the information of the sexual roles shown by the convention of “×”, the description of the characters contributes to forming images of seme and uke. In the first combination, The Inca noble is accompanied by the word ‘beautiful’ showing that he is more feminine than the Spain Invader; while adding the word strongest gives the impression that he is more powerful than the roman general whose rank is higher.

The three provided examples demonstrate that it is not necessary to apply excessive female codes on the uke, or over-masculine ones on seme. Simple gender codes will provide sufficient comparison needed to decide the sexual roles of the characters. Thus, both Watanabe and Nagakubo are similar in the way they of distinguish the seme and uke by comparison although the criteria – gender appearances and hierarchical relationship – they use differ.

The challenge addressed by the present paper is how to see the coded differentiation in the form of illustration instead of written text. Readers take less time to look at a picture than read a text, yet they can discover the same amount of information, if not more, on said subject.

One way of determining visual clues from a character is by adapting Inuhiko Yomota’s character codes, a methodology he proposed in Manga Genron (1994) (Principles of Manga) to define character drawings. Character codes were originally proposed by Yomota to discover how a single character can be recognized through different drawings, as there was nothing such as the same precise drawing in manga. In the chapter of Characters Codes,

Yomota stated that every recurring character in manga has three basic codes that he named character codes (kyarakutā kōdo): default persona code (tōjō jinbutsu kōdo), emotion code (kanjō kōdo), and action code (kōdō kōdo). Default persona code is the code used repeatedly in order for a character to be recognized in various drawings. This code is the initial code that is unique for every character. For example, a character’s face shape, eye shape, mouth shape, and hair vary according to the drawn scenarios, but the initial shapes are similar. Emotion code is the code that shows the emotion of the character, for example, the mouth and eyebrows, where changes in shape can signify different emotions of the characters. The last of the codes show the action of the characters, portrayed by the usage of characters’ limbs, thus the term ‘action code’.

Characters codes were initially intended to track one character throughout different drawings, but this research is adapting the same rules proposed by Yomota to find shared codes of respectively seme character and uke character and discover the visual differences between the two.

Persona codes can provide gender clues for the characters. For example, thin eyebrows, longer eyelashes, thinner lips, and a small jaw can give a feminine impression to a character, sufficient for him to be identified as an uke. However, such persona codes are not definitive if only one of the characters is present. Another character – presumably his counterpart – needs to be drawn next to him in order to unveil the gender difference. Similar to the thesis proposed by Nagakubo in the case of novels, a firmer assumption can be made by comparison of the drawings of the two characters.

The set of three figures below demonstrates an example of the importance of gender differentiation by persona code. Fig. 2-i shows an opening illustration of Akira Kanbe’s Torokeru hodo Aishiteru (2006) (I Love You So Much I Feel I’m Melting). From the first, it is clear that the character depicted on the left has more feminine facial features and a smaller build than the character depicted on the right, giving the impression that the character on the left side is the uke. However, if the uke character is replaced by a drawing of a man with sharper eyes, thicker eyebrows, and more muscular as seen in Fig. 2-ii, the illustration now gives the impression that the character on the right is an uke. A different interpretation can be made if the character on the right side is replaced with a boy of more feminine features as

shown in Fig. 2-iii; the character on the left side can now be seen as seme. This example shows that depiction of two characters is needed to provide a frame of reference and therefore comparison is required to determine the sexual roles of the character.

Nevertheless, there are cases in which gender differentiation cannot be distinguished by comparison. These occur mostly when the seme and uke have similar persona codes making

Fig. 2-i. Opening Illustration of Torokeru hodo Aishiteru (2006) by Akira Kanbe

Fig. 2-ii. Alteration of the uke character depicted in Fig. 2-i

Fig. 2-iii. Alteration of the seme character depicted in Fig. 2-i

it difficult for the readers to find significant gender differentiation. Fig. 3 is a prime example for this case. The two different characters depicted in this case, Yūka Nitta’s Flight Control (2006), have no significant differentiation on their persona codes. They have almost similar eye shapes, eyebrows, lips, and face shapes, although they have different eye color and hair. However, the author presumably drew the characters in such a deliberate way due to the fact that her series Haru wo Daiteita (Embracing Love) is one of the rare examples of BL characters switching their sexual roles. However, if the characters are not intended as one with reversible sexual roles, the visual clues of their sexual roles are found by looking at other provided character codes – the emotion and action codes.

Emotion and action codes of seme and uke characters showcase differentiations which are not related to the physical aspect of gender identity. Instead, they reveal power and dominance inequality. The seme will have with expressions or postures indicative of power and dominance, while the uke will be showing shyness and fragility. Inequality in power and dominance can also be represented by objects: clothing and text with information about their social ranks and positions.

However, emotion and actions codes are the components that can trump such objects, as shown in the next example. The color spread for Yaya Sakuragi’s Nee, Sensei? (2006) (Hey, Teacher?) in Fig. 4 is an opening illustration for the story of the romance between a teacher and his student. The two characters are depicted in their uniforms, and the written text also provides

Fig. 3. Opening Illustration of Flight

Control (2006) by Yūka Nitta

additional explanation about the background of the characters. In a school environment, the teacher should rank more superior to the student. However, the teacher wears a submissive expression and his hands are held by the student, who has a seductive smile and eyes, with one of his hands is taking the teacher’s hands and the other on the teacher’s shoulder. This gives the impression that the student is the seme and the teacher is the uke; overthrowing the standard of social inequality given by the connotative meanings of the objects and text. Emotion and action codes in this illustration imply the differences between the characters, shown due to the similarities of the persona codes.

Emotions and action codes are the most powerful codes to signify differentiation between couple characters in BL genre. Persona codes probably have different bars of differentiation according to the situation due to the diversity of character designs. However, emotions and actions to show dominance and submission are fundamentally universal in most cases. BL readers in particular will know when the sign reappears in different cases, and can instantly associate the said emotions and actions with a sexual role. Emotion and action codes can even override differentiation by persona codes, and often are sufficient to show the sexual role of a character even if the character is depicted alone.

Examples of strong emotion and action codes on singular characters can be seen from the next examples. Fig. 5 shows the illustration of Piyoko Chitose’s manga Kaikan Mugendai Sapuli (2007) (Supplement for Infinite Ecstasy), in which a blushing character willingly shows his anus towards the reader. His emotion codes are depicted by the raise of eyebrows,

half-Fig. 4. Opening Illustration of Nee, Sensei? (2006) by Yaya Sakuragi

lidded eyes, half-opened mouth showing submission and the blush on the cheeks showing embarrassment. These are the emotion codes of uke that also was seen before in Fig. 2-i and presumably in various case uke expressions. He also has his hands on his buttocks to show his anus, suggesting the possibility of him using it to achieve sexual pleasure. This encourages the immediate conclusion that the character is an uke. This can also apply to seme characters, for example in Fig.6, an opening illustration for Reibun Ike’s Tokage to Chōzukai (2008) (Lizard and Hinge). Through the sharp angle of his eyes and eyebrows, the character displays a grim, stern, and powerful stare which, in conjunction with his crude action of pulling someone’s feet and biting its toes shows that he is the dominant figure in the relationship.

Fig. 5. Opening Illustration of Kaikan Mugendai Sapuli (2007) by Piyoko Chitose

On the other hand, the absence of emotion and action codes make it more difficult for a reader to assign a sexual role for the character, as shown previously in Fig. 3, and now in in Fig. 7, an opening illustration for Kai Tsurugi’s Yume wo tsugu mono – Kuro no Kishi (2006) (Heir of A Dream – Black Knight). This type of illustration can be a double edged sword, because by not giving a hint of the sexual roles, the readers will be drawn to read the book out of curiosity, but it will not appeal to readers who have specific taste in BL pairings, and are unsure if the book will satisfy them.

This leads to another reason why pairing is important in BL: that one of the ways of reading BL is reading the pairing (Fujimoto 2007, 42; Kaneda 2007, 52). Readers have different

tastes with regard to relationship and tension between seme and uke. Any form of text that delivers information on the pairing allows them to choose according to their preferences similar to an ‘order made’ feature (Fujimoto, ibid.). In case of written text, combination by the “×” symbol is the simplest form of stating the differentiation; while in illustrations, iconic differences can be found by seeing at the Character Codes.

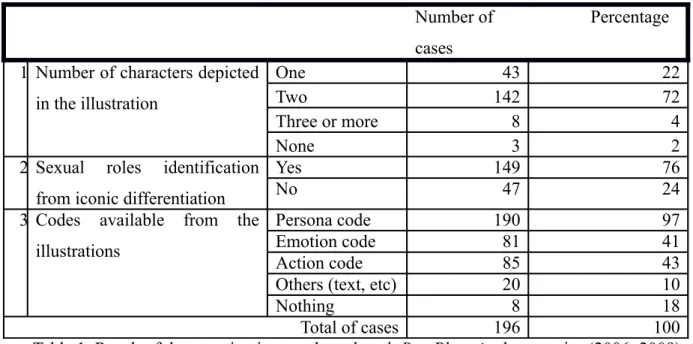

The examples of the study cases in the previous section show that an illustration depicting two characters together will provide differentiation that is needed to determine the sexual role of each character. The examination of character codes is conducted by performing study cases on the opening illustrations for all twenty issues of BL manga anthology b-Boy Phoenix (2006–2009) which consists of 196 short stories. The result shows that 142 out of 196 cases have two characters depicted together on the opening illustrations. This signifies the importance of both the seme and uke in representing BL story and the importance of the comparison to differentiate the two characters.

Number of cases

Percentage 1 Number of characters depicted

in the illustration

One 43 22

Two 142 72

Three or more 8 4

None 3 2

2 Sexual roles identification from iconic differentiation

Yes 149 76

No 47 24

3 Codes available from the illustrations

Persona code 190 97

Emotion code 81 41

Action code 85 43

Others (text, etc) 20 10

Nothing 8 18

Total of cases 196 100

Table 1. Result of the examination conducted on b-Boy Phoenix short stories (2006–2009) The result above also shows that there are 115 cases (60%) of the illustrations in which seme and uke can be distinguished by comparing persona codes. This proves the popular belief

that BL still depicts the physical appearance of the uke character as more feminine than the seme. In the same subject of persona code, 75 (38%) of the cases showing that sexual roles of the characters cannot be determined by persona codes alone, indicating that either seme and uke have very similar appearances, each is depicted alone, or neither is depicted in the illustration.

In the cases of emotion and action codes, from 81 cases of characters bearing obvious emotion codes, 78 cases shows the differentiation of seme and uke; while 83 out of 85 cases of action codes also displayed differentiation by action codes. These results show that despite the least frequency of appearance, the two codes provide more definitive information regarding sexual roles.

The examination conducted on these study cases shows no exact pattern in BL pairings, which is representative of the diversity in BL works. Regardless, the methodology conducted here highlights the process in determining the iconic differences between paired characters, which brings the result that is similar to the popular opinion of diversity in BL.

Comparison of either gender appearances or power and dominance between the characters can show differentiation which provides information on their sexual roles. However, differentiation by comparison is a tool that is not uniquely applied to BL. When similar codes reappear on characters and subjects that are out of context of BL, it is possible for the readers indoctrinated in BL to reinterpret non-romantic relationships of the characters outside of BL texts into romantic ones. It has become a new avenue of reading for the readers accustomed to reading BL. The evidence of this phenomenon is the flourishing of dōjinshi culture in Japan. As early as 1970s, the growth of BL was nurtured by fan activities offline by the existence of fan conventions and online after the spread of internet. Fan based conventions such as bi-yearly Comiket6 provided a place for fans to sell self-published fanzines such as dōjinshi, which contents are forms of parody of already existing manga, anime, drama titles or other cultural and sub-cultural works. By 2005, each Comiket convention contains twenty three thousand booths and is visited by roughly four hundred thousand people of approximately 75% consists of female visitors who generally are in favor of the BL genre (Komiketto Junbikai 2005, 290, 300). The majority of dōjinshi cast the friendship and/or rivalry between two male characters in

a romantic light. Booths in these conventions are organized by pairings and characters combinations from the mainstream, series, and this organization then became the map for like-minded fans to find one another.

This growth of fan activities also shows the expansion of BL as a sub-culture, helped by pro-active participations of consumers. It has become a phenomenon in which the motivations of consumers toned not to be justified nor questioned anymore. The growth encourages it to read it as a text of its own.

In this paper, BL works display differentiation between two characters that instantly introduced the readers to the coupling presented in the story. In written text, these differentiation are designated by a simple “×” between character names or descriptions, while visual image showed the iconic differences through character codes. The differentiation in both written and visual text is fundamentally based on gender appearances and power or hierarchical dominance as stated by Nagakubo and Watanabe. However, this genre is still growing and is nurtured in part by the initiative of the BL fans challenging the clichés. In present time, the combination of pairing has jumped the barrier of animate characters into the realm of inanimate objects, giving rise to anthropomorphic pairings such as spoon and fork, buildings, countries, animals, retail stores, stations, and weathers. Determining the basis of differentiation in these novel types of pairings, whether fundamental or iconic will prove an interesting subject for the future.

Bibliography

Fujimoto, Junko. 2007. “Kankeisei kara miru BL no genzai” Eureka Vol. 39 No.16, December. Fujimoto, Yukari. 2007. “Shōnen ai/Yaoi・BL 2007 nen genzai no shiten kara” Eureka. Vol. 39

No.16, December.

Hanamaru Henshūbu. 2004. Bōizu Rabu Shōsetsu no kaki kata. Tōkyo: Hakusensha.

Hori, Akiko. 2009. Yokubō no Ko-do – Manga ni Miru sekushuariti no Danjosa. Tōkyō: Rinsen Shōten

Ishida, Miki. 2008. Hisoyakana Kyōiku - <Yaoi・Bo-izu rabu> Zenshi. Tōkyō: Rakuhoku Shuppan

Kaneda, Junko. 2007. “Manga dōjinshi – Kaishaku no kyōdōtai no poritikkksu” In Bunka no Shakaigaku, edited by Kenichi Satō, Shunya Yosmihi, 163–190. Tōkyō: Yūhikaku Arma. Kaneda Junko. 2007. “Yaoi ron, ashita no tameni sono 2.” Eureka Vol. 39 No.16, December. Kurihara, Chiyo. 1993. “Tanbi shōsetsu” In Tanbi shōsetsu Bukku gaido, edited by Eiko

Kakinuma and Chiyo Kurihara, 325–368. Tōkyō: Byakuya Shobō.

Komiketto Junbikai. 2005. Komikku Ma-ketto 30’s Fairu. Tōkyō: Seirinkōgeisha. Miura, Shiwon. Kaneda, Junko. Saitō, Mitsu.

Miura, Shiwon, Kaneda, Junko. 2007. “’Seme x Uke’ wo mekuru sekai – Dansei shintai no miryoku wo motomete” Eureka Vol. 39 No. 7, June.

Mizoguchi, Akiko. 2000. “Homofobikku na Homo, Ai yue no Reipu, soshite Kuia na Rezubian” Queer Japan Vol. 2, April

Mizoguchi, Akiko. 2003. “Sore wa, Dare no, Donna ‘riaru’? – Yaoi no Gensetsu Kuukan wo Seiri suru Kokoromi” IMAGE&GENDER Vol. 4:27–55

Nagakubo, Yōko. 2005. Yaoi Shōsetsuron – Josei no tame no Erosu Hyōgen” Tōkyō: Chikuma Shobō.

Nagakubo, Yōko. 2007. “Josei tachi no ‘kusatta yume’ = ‘yaoi shōsetsu’ – yaoi shōsetsu’ no miryoku to sono mondaisei” Eureka Vol. 39 No. 7, June.

Nakajima, Azusa. 1987. Bishōnen Nyūgakumon. Tōkyō: Shūeisha

Nakajima, Azusa. 2005. Tanatosu no kodomo tachi – Kajōtekiō no seitaigaku. Tōkyō: Chikuma Shobō.

Nobi, Nobita. 2003. Otona wa Wakatte Kurenai. Tōkyō: Nihon Hyōronsha

Sugiura, Yumiko. 2006. Fujoshika suru Sekai Higashi Ikebukuro no Otaku Joshi tachi. Tōkyō: Chūko Rakure

Ueno, Chizuko. 1998. Hatsujō Souchi Erosu no Shinario. Tōkyō: Chikuma Shobō.

Ueno, Chizuko. 2007. “Fujoshi to wa dareka? – Sabukaru no Jendā – Bunseki no tame no oboegaki” Eureka Vol. 39 No. 7, June.

Watanabe, Yumiko. 2007. “Bishōnen manga kara miru ‘yaoi’” Eureka Vol. 39-No.7, June. Yamamoto, Fumiko. 2005. Yappari Bo-izu rabu ga suki ~Kanzen BL komikku gaido~. Tōkyō:

Yamamoto, Fumiko. 2007. “2007 nen no BL kai wo megutte – soshite ‘fujoshi’ to wa dareka” Eureka Vol. 39 No. 16, December.

Yomota, Inuhiko. 1994. Manga Genron. Tōkyō: Chikuma Shobō.

Yoshinaga, Fumi. 2007. Ano Hito to Koko dake no Oshaberi. Tōkyō: Ōta Shuppan. Samples:

Libre Editorial. b-Boy Phoenix Volume 1 – 20. 2006–2009. Tōkyō: Libre Shuppan Norikazu, Akira. 2007. Hāto♥ Sotirungusu. Tōkyō: Libre Shuppan

Takemiya, Keiko. 1993. Kaze to Ki no Uta Chūkō Aizōban. Tōkyō: Chūōkōronsha

Tezuka, Osamu. 1982 Tezuka Osamu Manga Zenshū 241 Atomu Konjaku Monogatari Vol. 1–2. Tōkyō: Kōdansha

Unit Vanilla. 2007. SASRA 2. Tōkyō: Libre Shuppan.

Febriani Sihombing is Ph.D. candidate majoring in Media and Semiotics, in Human-Social Information Science Department, Graduate School of Information Science, Tohoku University.

1The classification of manga into genres such as shōnen manga and shōjo manga is not found in earlier manga history. These two terms originally practiced by the market to refer to the target readers instead of the visual narrative style of the manga (Itō 2005, 13) such as paneling, words and character designs. The styles of the said genres were later differentiated by active parties whom are involved in the manga business (ibid). However, these two styles are lately seen overlapping each other (ibid.) Thus, it’s more appropriate to state that the genre in modern manga is not based on the of the visual narrative style of manga, but to the target readers such as

seinen (men) and josei (women), or themes of the story such as BL and lolicon (lolita complex) manga.

2Through history, BL has adopted several names such as shōnen ai, yaoi, JUNE, and Boys Love. Each of the names is rooted on different aspects in BL phenomenon. Shōnen ai, the name popular in the earlier history of BL, came from the depiction of beautiful adolescent boys (bishōnen) in love (ai) that is generic in that era of BL history (Mizoguchi 2003, 29). JUNE is named adopted from the title of a prominent BL magazine that helped the spread of this genre (ibid, 30). Yaoi is a name based on the nature of fan-made works with lack of story contents and excessive depiction of sexual situations. BL itself is a name proposed by famous BL magazine B-BOY in the 1990s (ibid, 31) due to the connotation of yaoi, the genre name popular at the time. The differences of the name often misapprehended, leading fans to categorize sub-genre such as shōnen ai to be a story with no explicit sexual depictions and yaoi as a story with graphic visuals of sexual situations.

3There are theories stating that bishōnen is an evolved form of “beautiful women in men’s clothing” (dansō suru

reijin) characters that was popular before the emergence of BL (Ueno 1998; Fujimoto 2007). These theories are

implemented in gender studies showcasing BL. The studies mainly propose a thesis that dressing women with men’s clothes is representing their desires to overcome the gender barrier (Ueno ibid; Fujimoto ibid).

4In the present days, the term bishōnen has expanded, shown by the emergences of similar terms. For example,

biseinen (beautiful men) and bichūnen (beautiful middle age men) that both refers to male characters with the

same characteristics of bishōnen but with different age class.

5Especially after a serial killing incident in the late 1980s which is committed by Tsutomu Miyazaki, an otaku – a fan of manga, anime, and related sub-culture works, this sub-culture was regarded negatively by the Japanese society. The book Nakajima written in the subject of BL reading females elevated the public negative opinion towards female otakus in particular, regarding them to having an “illness” that is in dire to be cured (Kaneda 2007, 168).

6Comiket is the biggest anime, manga, and related culture convention in Japan. It opens approximately twenty three thousand booths of mostly non-commercial booths publishing self-funded magazines.