Development of a Design and Evaluation Framework for Supplier Cities by

Jason Antoine Mellein (p)

Bachelor of Arts in Physics, Occidental College (1995) and

Daniel Allen Shockley (a)

Bachelor of Science in Metallurgical Engineering, University of Missouri - Rolla (2001) Submitted to the Engineering Systems Division, the Department of Mechanical Engineering, and the

Sloan School of Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of

Master of Science in Engineering Systems

0.,

Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering

",

and

Master of Science in

Management'

In conjunction with the Leaders for Manufacturing Program Massachusetts Institute of Technology

June 2007

C 2007 Massachusetts Institife of Technology. All rights reserved.

Signature of Author

I 7 1-7

Signature of Author

Certified by_

Professor of Mechan

MIT Sloan School of Management Engineering Systems Division

/4IT Sloan School of Management Mechanical Engineering

David Hardt, Thesis Supervisor ical Engineering and Engineering Systems

Certified by IV

-- \ Richard Locke, Thesis Supervisor

Professor of Entrepreneurship and Political Science, Sloan School of Management Accepted by

Debbie Berechman, Jxecutive Director of Masters Program MJT Sloan School of Management Accepted by

A'epted by Richard de Neufville, Chai 0nof ttee on Graduate Studies SPjiso Engineering Systems Division

MASSO TECHOLyc

epted

byM ITLib ries

Document Services

Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 Email: docs@mit.edu http://Iibraries.mit.edu/docsDISCLAIMER OF QUALITY

Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable

flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to

provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with

this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as

soon as possible.

Thank you.

A Design and Evaluation Framework for Supplier Cities and Application to Timken, China

by

Jason Antoine Mellein (pt) and

Daniel Allen Shockley (a)

Submitted to the Engineering Systems Division, the Department of Mechanical Engineering,

and the MIT Sloan School of Management on April 15, 2007 in Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements for the Degrees of

Master of Science in Engineering Systems

',Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering

",and

Master of Science in

Management

Abstract:

For companies pursuing opportunities by expanding manufacturing to new markets, one major challenge is unavoidable: identifying and developing capable, local suppliers. In developing markets suppliers often lack the cutting edge technology, processes, and management

methodologies driving the world's best businesses. The ability to identify and develop, relocate or build suppliers with World-Class capability becomes a competitive advantage. This thesis discusses the state of the art in Industrial Conglomerations (including Industrial Clusters and Supplier Cities) as well as their benefits and limitations. To analyze the potential opportunity for manufacturing firms considering supplier cities, we have developed a technical, operational, and financial framework for considering the opportunity and making key decisions about structure, location, and included processes. The framework includes a discussion regarding process selection based on an analysis of critical technical issues at each manufacturing step. This analysis considers the relationship of process capability to overall product performance and ultimately to product competitiveness. In an attempt to help justify the effort of the host

company in establishing a Supplier City, we include a discussion of the cost model we developed to quantify the benefits associated with supply chain expense, learning curve effects, and the expense of developing suppliers located in Supplier City versus those located elsewhere. We further discuss the legal, political, social and environment risks of Supplier City and guidelines for stakeholder focused management of local, regional and national governments, party officials, and NGO's. Finally, we include a case study in which we apply our framework to The Timken Company's China operations. We discuss their specific case and our recommendations.

Thesis Supervisor: David Hardt

Title: Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor: Richard Locke

Acknowledgements

The foundational work for this thesis was completed by Sabrina Chang, Jason Mellein, Christopher Porter, and Daniel Shockley during the Fall of 2006 and Spring of 2007 in conjunction with the MIT class - Global Entrepreneurship Laboratory (GLab). That work culminated in the creation of a white paper titled "Supplier City Concept for Timken in

China". We would like to thank Sabrina and Chris for making the experience, fun, rewarding and memorable. Their excellent work and contribution helped us add to the cumulative knowledge base for supplier co-location, offering companies a new competitive weapon.

We would also like to thank David Hardt and Richard Locke for their support as our academic advisors for this work. Their input and guidance helped us to discover many relevant bodies of research and deepen and richen our understanding and contribution through this work.

A large number of individuals provided critical support in the execution of this study. First, we thank Roger Lindsay and Richard Locke for creating and supporting this opportunity to offer an internship of this caliber to the GLab course. From Timken Company we thank Paul Henry and his Executive Assistant Lan Shao (Kate) for their consistent, self-less support. Their timely response to requests for data, logistics support, and access to Timken personnel and suppliers proved critical to completing this study in the time allotted. In particular the large degree of time Paul personally devoted to being interviewed by us provided invaluable insight into Timken's China and Global operations. We also specifically thank Doug Smith for being an excellent sounding board for our ideas and analysis and for injecting the sorts of realistic understanding of a manufacturing operation academics may miss. At the Shanghai office we thank Ajay Das, and Rajat Modi for their eager participation, insight, and contributions. Particularly in the pre-on-site stages of the study, conference calls with the Timken team gave us the background necessary to hit the ground running in China. Xiaoyan Qin (Helen), Doug Smith's Executive Assistant, provided continued logistical support once we moved from LiYuan to Wuxi 1 in the second week.

Also from Timken, we thank the sourcing engineers: Calvin Lee, Ji Gong, Keen Gao, Shi YongLiu, Mike Sun, and Bruce Mi. They provided insight and data behind Timken's suppliers and supplier development policies, capabilities, and opportunities. These were the real

"where the rubber meets the road" conversations that took our analysis from theoretical to practical.

Additionally, we want to thank Peter Malik for providing a detailed discussion of Supplier City Concepts from his point of view. His perspective challenged us to think on new, more strategic levels and our study is considerably stronger for our time spent with him. We'd also like to thank him for introducing us to some of Wuxi's culture. Sherry Zhao happily provided a distinctly intricate view into relevant Chinese legal structures. Our discussion with her revealed both the possibility and complexity of developing a Supplier City in China. From MIT we thank our professor Shari Loessberg who served as a consistent touch-stone and process advisor in completing the first half of our study, stateside, as well as ensuring we prepared properly for our travel to China. Her assistance helped ensure we stayed on track, on focus, and on time. Trond Wueliner, the GLab TA, provided similar support.

Table of Contents

A cknow ledgem ents...

5

C hapter 1: Introduction ...

11

In c ep tio n ... 1 1 Problem Sum m ary and Justification... 11

Overview of M ain Results ... 12

Chapter 2: Review of Industrial Conglomerations...14

O v erv iew ... 14

Industrial Parks ... 15

Industrial Clusters / A gglom erations ... 16

Industrial Districts... 17

Supplier Parks ... 17

Supplier Cities... 19

Conglom eration Developm ent and Risks ... 21

Spill-over Effects of an Industrial Conglomeration... 22

V irtual versus V ertical Integration... 23

Supplier City Concept Detail... 24

P u rp o se ... 2 4 Description of a Supplier City ... 25

C hapter 3: Strategic Issues ...

31

V alue Creation vs. Value Capture ... 31

M arginal Benefit vs. M arginal Cost... 32

Com plexity vs. Risk... 34

Deploym ent Phasing ... 34

Learning Effects... 35

Foreign-D om estic Capability Curves ... 36

Chapter 4: Supplier City Scenario Design and Evaluation Framework...40

The Null Hypothesis ... 40

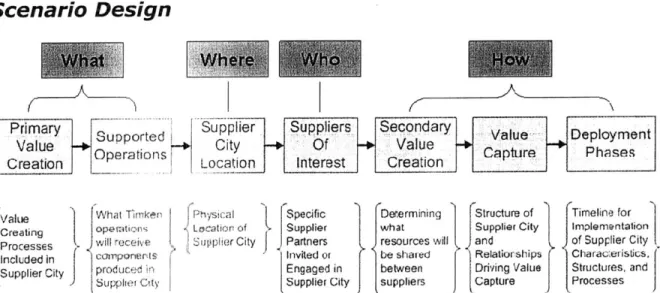

Scenario D esign ... 40

Prim ary Value Creation - Process and Component Selection... 41

Supported Operations - Supplier City Custom ers ... 41

Supplier City Location... 42

Suppliers of Interest ... 42

Secondary Value Creation - Resource Sharing ... 43

Value Capture Profile ... 43

Deploym ent Phases... 44

Scenario Evaluation ... 45

Down-Select Process ... 45

D im en sio n s ... 4 5 L e v e rs ... 4 9 M anufacturing Process Selection M ethod ... 49

Value Chain Analysis ... 50

Technology Transfer ... 52

S u p p ly C h a in ... 54

Lead Time Reduction ... 54

Cycle Stock Reduction ... 55

Safety Stock Reduction ... 56

Operations M anagement ... 57

L earn in g C u rv es ... 57

Geographic Proximity and Partner/Supplier Development ... 59

Issues in the Creation and Development of a Supplier City ... 60

In d u stry ... 6 1 C lo c k sp e e d ... 6 1 C o m p lex ity ... 6 1 G lo b alizatio n ... 6 2 M a tu rity ... 6 2 Supplier Population ... 62

Country / Locale Risks ... 63

C u ltu re ... 6 3 Industrial M aturity ... 63

IP P ro tectio n ... 6 3 Labor Costs and Availability ... 64

Economic Development Zones ... 64

C u sto m s ... 6 4 T ran sp ortation ... 6 5

C hapter 6: A pplication to Tim ken

...

66

O v erv iew ... 6 6 Timken Characteristics ... 67

Core Competencies ... 67

Tim-ken's Supply Chain in China ... 67

The China Business Environment ... 68

C h in ese C u lture ... 6 8 IP P ro tectio n ... 6 8 Labor Costs and Availability / Special Economic Zones ... 68

Bearings Industry Overview ... 69

In d u stry siz e ... 6 9 M a tu rity ... 6 9 C om p lex ity ... 6 9 B u ild in g S cen ario s ... 6 9 W h a t ... 7 0 W h ere (L ocation s) ... 7 1 W h o & H o w ... 7 2 Comparing Scenarios ... 73 W e ig h tin g ... 7 3 V alu e C reated ... 7 4 Value Capture Profile ... 74

C om p lex ity /R isk ... 7 4 Recommendation Reprise ... 75

Summary of Contributions

...

76

R eferences

...

77

A ppendix A : Term inology

...

80

A ppendix B : R esearch

...

84

P lan t T o u rs ... 84

In terv iew L ist

...

84

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Level of Coherence of Industrial Conglomerations ... 15

Figure 2: Industrial Conglom eration Attributes... 21 Figure 3: Potential Value Flow-down Pathways ... 29

Figure 4: This figure highlights, visually, the difference between Value Creation and Value Capture. Companies that focus on creating value to be shared among all partners create more collaborative relationships than those that focus on capturing a larger portion of the existing value... 32

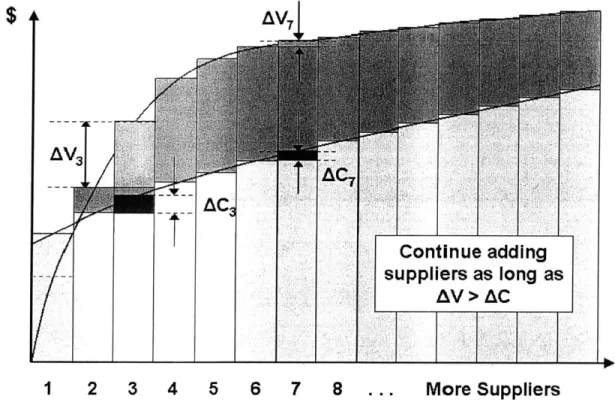

Figure 5: Illistration of a Marginal Cost vs. Marginal Benefit analysis. Suppliers are represented as independent and are ordered by decreasing marginal benefit... 33

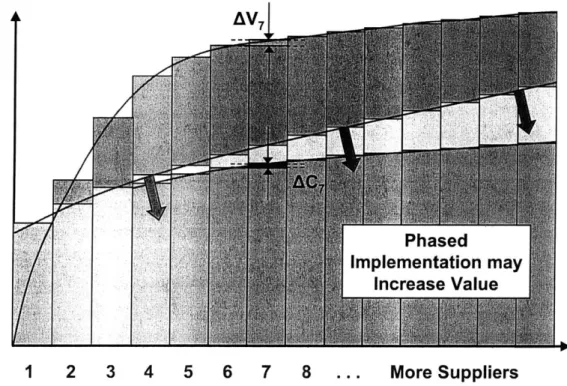

Figure 6: Illustration of the impact of previous Supplier City implementation on the addition of subsequent suppliers. ... 35

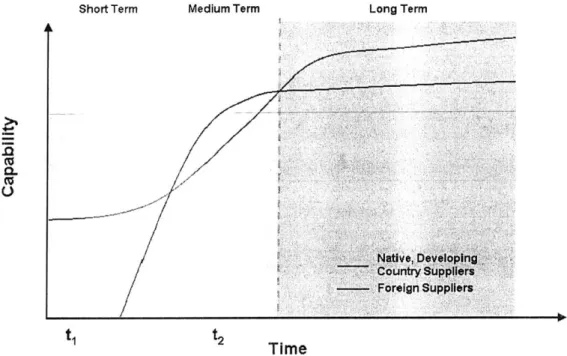

Figure 7: Foreign vs. Native Supplier Capability Curves w/out Supplier City shows that the local supplier is immediately able to deliver product due to their local presence. The foreign supplier is delayed because they have to relocate operations to the host

lo c atio n ... 3 8

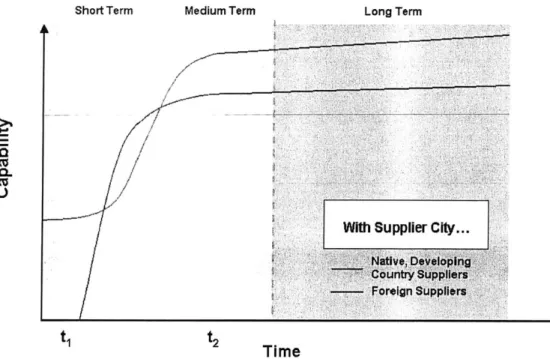

Figure 8: Foreign vs. Native Supplier Capability Curves w/ Supplier City. Due to the Supplier City, both curves are shifted to the right and the rate of improvement increases due to shared infrastructure, improved communication and technology transfer between the host and other Supplier City participants... 39

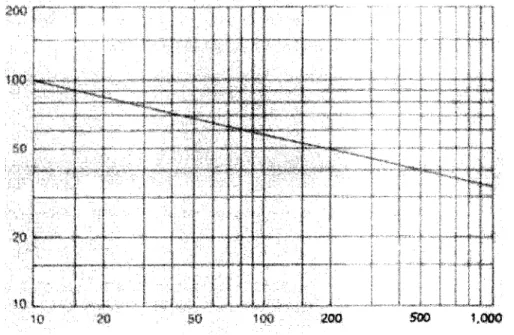

Figure 9: Graphical Representation of Scenario Design Process ... 40 Figure 10 - An 85% experience curve. The horizontal axis is the accumulated volume of

production (in units), and the vertical axis the deflated direct cost per unit (corrected for in flation ) 6] .. .. ... 5 8

Figure 11 - A log-log graph of an 85% experience curve expressing the relationship between the

accumulated volume of production (horiz axis) and the deflated direct cost (vertical ax is) 161.. . . ... ... 5 8

Chapter 1: Introduction

Inception

This work began as a study of the viability and usefulness of creating a Supplier City for Timken China. The project centered on an internship for the Global Entrepreneurship Lab

(15.389) class at MIT's Sloan School of Management and included a team of four Leaders For Manufacturing (http://Ifm.mit.edu) fellows: Sabrina Chang, Jason Mellein, Chris Porter, and Daniel Shockley. The original project produced two documents: a white paper and a presentation aimed at Timken China's corporate leadership. Sabrina Chang and Chris Porter were invaluable members of the team, working tirelessly, providing key insights, and contributing strongly to the aforementioned artifacts. For their contributions we are extremely grateful. Further development of the analysis, post-project, of Industrial

Conglomerations, Process Selection techniques, and Cultural, Country, Risk, Spill-over, and other aspects was conducted by the authors of this thesis.

Problem Summary and Justification

Since the beginning of the industrial revolution in the United States and Europe, one manufacturing decision has been the focus of many manufacturing strategies - whether to do work in house, or outsource processes and components. In today's manufacturing environment with short product and technology life cycles and extreme competition in both the marketplace and the capital markets, many companies have outsourced an increasing portion of the manufacturing of the products that they sell. In many cases these decisions have had a tremendous impact on the short-term and long-term success of companies. In some cases outsourcing has led to explosive and sustained success allowing companies to focus on activities such as creative development (e.g. Nike and Apple), and in others the decision led to erosion of market power and eventual dissolution or renewal (e.g. IBM and Intel/Windows).

In today's global economy companies expand into new markets to tap a larger pool of customers, as well to develop a larger manufacturing base. These activities are critical to many companies' sustained viability. At present, many multi-national companies are struggling to replicate the supply capability to which they have become accustomed in developed countries in each new countries of operation. This dynamic forces them to re-evaluate their outsourcing decision as well as invest tremendous amounts of human capital

resources in developing capability in new suppliers and relocating old ones. In some cases, the most attractive option can be to establish a higher degree of vertical integration. Many companies are looking for ways to get the advantages of vertical integration accompanied by the competitiveness of a properly though out outsourcing strategy - what we will call Virtual Vertical Integration.

Supplier Cities, Industrial Districts, and Clusters are examples of what we have termed Industrial Conglomerations. An Industrial Conglomeration (IC) is a collection of firms in close geographic proximity with complementarities and synergistic effects with some aspect of the locale and, in many cases, between the firms themselves. In a Supplier City, a host company invites a selected array of suppliers to co-locate in close geographic proximity to the host in order to improve the supply chain and logistics performance of the overall enterprise. This type of conglomeration represents the highest degree of structural coherence of both corporate and physical relationships in any of the IC's due to shared investment in resources and/or infrastructure, the physical contiguity of the participants, and the highly structured and intricately designed nature of inter-corporate physical relationship (e.g. component delivery via dedicated systems). Our subject company,

Timken, is considering the development of a Supplier City in a developing region to leverage such effects and asked us to examine the concept in detail vis-h-vis the location specific aspects of their operations.

We believe there is great value to companies, industries, countries, and locales in having a formal understanding of the different types of Industrial Conglomerations and the relevant forces and issues that shape their development and affect their success or failure. Industrial Conglomerations can positively affect competitive advantage at the firm, industry, and country level as well as generate economic growth and innovation. Understanding how to design and develop a conglomeration and avoid the pitfalls in doing so can greatly benefit firms, industries, and countries. For some industries the strategic implementation of a

Supplier City can become a competitive weapon providing the efficiency of vertical integration with the flexibility of an outsourced supply chain.

Overview of Main Results

In this work, we complete a review of existing definitions for the different types of Industrial Conglomeration incorporating existing sources and literature and introduced the

Conglomerations and brings together multiple academic works on the topic. In addition, we demonstrate the numerous benefits that come from the organization of a Supplier City by a host company and assert that a successful Supplier City implementation can have the result of a sustainable competitive advantage. To support this objective, we establish a

framework for Supplier City evaluation and development. This tool helps companies identify whether or not there is an opportunity for them to develop a Supplier City, what processes and partners should be included in the Supplier City and how they should structure the relationships to distribute newly created value. The application of the framework will guide a company on a quest for a superior supply chain by directing the consideration of the myriad of important dimensions of each Supplier City implementation. In addition, we document a number of tools that can be used in to assess potential Supplier City options, benefits and opportunities. Finally, we present an analysis, within the context of the developed framework for the implementation of a Supplier City by Timken, China. The content of this work will assist companies in their evaluation of Supplier City opportunities

Chapter 2: Review of Industrial Conglomerations

In our research, we uncovered a number of different terms and structures to describe a geographic conglomeration of companies but no underlying framework to give a clear understanding of how the different types are related to and different from each other. The abundance of different names and characterizations for conglomerations, along with this lack of a framework for understanding the "design space", occasionally created confusion within our project team, between the team and Timken, and between the authors of this thesis. After some consideration, an underlying order began to appear to us and we

developed a framework for relating and characterizing different types of conglomerations. In this section we present the framework, its rationale, and give a detailed description of the various types of industrial conglomeration.

Overview

The patterns of inception, development, risk, and benefit of industrial conglomerations is a complex subject in an informal stage of development. They vary in the degree of

organization of inter-company relationships and geographic-positional structure. They also vary in what drives the creation of the conglomeration. On the one end of the spectrum there are conglomerations created for a specific purpose by a single organization with non-competitive partners (suppliers and, possibly buyers); and on the other end, there are conglomerations of companies involved in 'coopetition' who reap benefits from geographic proximity mainly through secondary effects. Secondary effects of the conglomerations themselves vary broadly depending on the environmental, social, and regulatory context of the conglomeration, the industry involved, and the specific distribution of companies across the overall value chain. While conglomerations of various types, sizes, and characteristics have grown, developed, and occasionally failed around the world for the past few decades there is little formal understanding of the distinguishing characteristics of the various types, the competitive advantages they render to stakeholders, or the nature of their development processes and how to encourage or shape them.

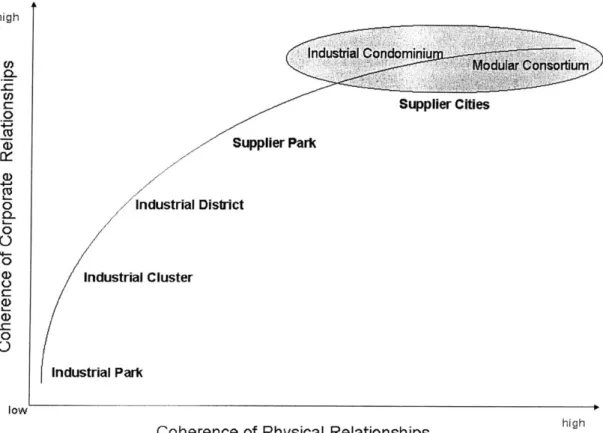

The different types of conglomerations vary in their degree of coherence of corporate relationships and physical relationships. On one end you may have a large number of firms located in geographic proximity but with no formal, designed, or mutually dependent

organizations may have a very high degree of mutual dependence and structure to their corporate relationship and may be physically connected to each other to facilitate the exchange of goods. The following chart illustrates the spectrum of conglomerations along two axes: 1) Coherence of Corporate Relationships; 2) Coherence of Physical

Relationships. high c Supplier Cities 0 (1) Supplier Park 0 industrial District L 0 0 I.-0 a) Industrial Cluster 0 Industrial Park low

Coherence of Physical Relationships high

Figure 1: Level of Coherence of Industrial Conglomerations

Industrial Parks

An Industrial Park is an area usually located some distance from a city center, designed and zoned for businesses and/or manufacturing and associated activities.[5' 33'361 Industrial parks are usually located close to transport facilities, especially where more than one transport modalities coincide: highways, railroads, airports, and navigable rivers.

An Industrial Park has very loose constraints on the scope of industry that may develop within it. Broadly divergent, unrelated industries may be represented by companies in an Industrial Park. Taken together with suppliers, partners, customers, and service providers who may create a presence within the Industrial Park to serve other related companies already there, and the possible industrial diversity is great. The average structural coherence of both corporate and physical relationships between any two organizations in an Industrial Park is very low.

Industrial Clusters

/

Agglomerations

Michael E. Porter-defines "Clusters" as "geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions in a particular field."E2

63 For the sake of semantic continuity between the various types of conglomeration discussed in this thesis, we here introduce the term "Industrial Cluster" as a synonym for Cluster. Industrial Clusters, like Industrial Parks, are comprised of multiple industries, but the industries are more closely linked and

interdependent. Further, the distribution of companies across the value chain for a given industry may be smaller than in Industrial Parks but is greater than the conglomeration types listed below and may include equipment manufacturers, channels, and soft services. Industrial Clusters are critical masses of organizations that, together, have distinctly greater success in a particular field than any other locality. Industrial Clusters appear to focus on multiple, but related industries. As noted by Porter, Silicon Valley and Hollywood are the world's most famous clusters. The average structural coherence of both corporate and physical relationships between any two organizations in an Industrial Cluster is somewhat higher than in an Industrial Park due to linkages between the represented industries. An example of an Industrial Cluster is the California wine cluster which includes 680 commercial wineries and several thousand independent grape growers[261. This

agglomeration further includes suppliers of wine-making equipment, barrels, bottles, caps and corks, labels, public relations and advertising, and specialized publications. This cluster does not have the wine industry as its single focus. The hospitality business plays a large and somewhat independent part, providing food, lodging, and tourism services for people traveling to the area. While they are synergistically related to the wineries, they do not provide services directly to the wineries or in support of the wineries primary business of producing wine. Instead this two foci system creates a convenient method of out-reach and marketing for the wineries while providing a business opportunity for the hospitality industry. Academic involvement is provided by the viticulture and enology program at University of

California, Davis, and the Wine Institute. This conglomeration is not centered on any specific commercial winery. Instead there are a multitude of players at every stage in the value chain (equipment, growers, wineries, academics, etc) all within close geographic proximity with a somewhat low average structural coherence between firms.

Industrial Districts

"Industrial Districts are geographically defined production systems characterized by a large number of small and medium-sized firms that are involved in various stages of the

production process in a particular industry." .Industrial Districts have a narrower

industrial scope than Industrial Clusters in that they tend to have a single focus on a specific industry, such as textiles. The firms present still engage in a broad set of activities across the value chain, but all focus on production relevant to a specific industry. Legal/Contractual relationships between firms tend to be more informal and flexible while

geographically/physically, there is not much difference from Industrial Clusters. The average structural coherence of both corporate and physical relationships between any two

organizations in an Industrial District is somewhat higher than in an Industrial Cluster due to the fact the district is dedicated to a single industry.

Textiles Industrial Districts in Italy have developed a sort of division of labor among the firms that promotes district-wide flexibility and productivity. They often specialize in a single phase of the production process. Firms are able to aggregate orders across multiple

customers within the district helping them to invest more aggressively in capital equipment and amortize the costs quickly. Studies comparing district based and non-district based textile firms in Italy show higher productivity and profit rates (ROI) for district based firms.

Further

Supplier Parks

A Supplier Park is a conglomeration designed around a single host organization in which all

other participants are suppliers of goods primarily to the host but possibly each other as well. The average structural coherence of both corporate and physical relationships between any two organizations in a Supplier Park is higher than in an Industrial District due to the Supplier Park's dedication to a single host organization. Toyota and Dell have made this type of conglomeration famous.

There are two basic sub-types to a Supplier Park. In the first, the Supplier produces its components remotely and warehouses them in the Supplier Park facility with inventory levels set to maintain the service level agreed to with the Host. The arrangement may be on consignment or the host may own the inventory once it enters the Supplier Park. In this model, warehousing space (capacity) for a particular supplier will most likely be 100% committed to components destined for use by the Host. In the second Supplier Park model, the Supplier sets up production operations within the Supplier Park itself. The Supplier's product is produced locally, enhancing cooperative efforts to maximize value. However, care must be taken to safeguard against the negative effects of loss-inducing excess capacity during low points in the market cycle. The Host may need to allow the Supplier to use excess capacity to supply other customers in order to maintain the Supplier's financial viability. Hosts may customize and hybridize these models in a variety of ways to suit specific organizational needs.

Toyota makes very effective use of a production based Supplier Park, meaning suppliers locate production capabilities in close proximity to Toyota's own assembly operations. Toyota has developed its supplier network for approximately 50 years and, as described by

Peter Hines[1 71, its supplier network characteristics include:

+ A many tiered system with high bought-in content at each level

+- A close and flexible long-term relationship between buyer and seller + A small number of direct suppliers

+ A reliance on small subcontractors (9 2% of Japanese manufacturing firms have 18 or less staff)

+ Price determination through costing: A high degree of inter-firm cooperation in setting prices for upstream components produced within the Supplier Park, based on a transparent understanding of the cost to produce those components.

+- A high degree of strategic and operational assistance given to suppliers

+' A high degree of supplier driven innovation

Toyota's system of supplier management follows the Kyoryoku Kai (Cooperative Circle) model in which a collection of an organization's most important suppliers are brought in close, both physically and organizationally, to increase trust, Just-In-Time production, Statistical Process Control, and Value Analysis / Value Engineering. So well developed is Toyota's system that 80% of the value of its products is provided by the Supply Chain

result, Toyota has been able to focus intensely on its core competencies of designing

vehicles customers want to buy, reliability engineering, and product development cycle-time reduction.

Dell's Supplier Park model is warehouse-based. Suppliers maintain inventories on consignment in shared warehousing facilities close to Dell's final assembly operations. Suppliers deliver components to Dell approximately every two hours on a Just-In-Time basis. Coupled with the fact Dell receives cash for customer orders at order time, and does not start building product until a customer has made an order, this JIT/consignment based system has provided Dell with a negative conversion cycle, meaning it pays for the

production of an order some time after being paid for its construction. Dell provides a significant amount of Supplier training and process development in the belief that such investment yields cost reduction benefits over time. Dell considers its core competency to be customization (frequently called Application Engineering in other industries) and has used its supplier network to shift unrelated value-added steps up-stream in order to focus its Fixed Cost basis on what it does best.

Supplier Cities

Supplier Cities occupy the highest point on our continuum of industrial conglomerations. There are two basic types: Industrial Condominiums and Modular Consortiums[lO]. Modular Consortiums represent both the highest point on the continuum as well as the highest degree in virtual vertical integration. The average structural coherence of both corporate and physical relationships between any two organizations in Supplier City is the highest on the spectrum. This result obtains because both host and supplier firms share the investment

in resources and/or infrastructure; the firms are physically co-located or, if separate, often have part-conveying infrastructure connecting their buildings; and the legal, or otherwise binding, aspects of their corporate relationships are highly structured and intricately designed.

Industrial Condominiums

In an Industrial Condominium, the host organization maintains direct control only over key manufacturing activities. The remaining activities are broken into logical modules and outsourced (production and frequently design as well) to well-trusted suppliers. These suppliers may or may not conduct operations under the same roof as the host organization

but are typically at least within close geographic proximity with formalized or dedicated lines of material flow and communication. The level of coherence in the physical/geographical

layout of the various participants and the level of coherence in the relationship between them are very high.

In 1995 to preparing for the launch of its Ka model, Ford introduced an Industrial

Condominium near its facilities in Valencia Spain. By modularizing the components involved and outsourcing them to producers within the Industrial Condominium, Ford reduced the number of components its own workers handled from 3,000 to 1,200. Ford outsourced 60 modules and components, reducing vehicle assembly time 25%. While the suppliers are under different roofs, they are in very close proximity and at least three of them have conveyor tunnels that transport finished modules from the supplier to Ford's facility for immediate integration on the vehicle assembly line.

Modular Consortiums

In a Modular Consortium, the principal organization has withdrawn from any direct

involvement in manufacturing or assembly, instead focusing its efforts on design, process sequencing, quality oversight, and schedule management. Generally, all work occurs in one or more facilities owned and controlled by the host organization. The level of coherence in the physical/geographical layout of the various participants and the level of coherence in the relationship between them are very high.

NASA's ground operations, at Kennedy Space Center, are one excellent example of this phenomenon. At Kennedy Space Center, NASA outsources the detailed design, manufacture, maintenance, operation of all ground support equipment (GSE), vehicles, and payloads. NASA's role is to develop mission and vehicle requirements and specifications, award contracts to private sector organizations, and to oversee the various contractors as they perform their duties. For instance, USA maintains (Orbiter Processing Facility), assembles (Vehicle Assembly Building), and integrates the payload (Launch Pad) into the Space Shuttle launch vehicle. Boeing processes, tests, and prepares International Space Station (ISS) modules and other cargo and experiments in the Space Station Processing Facility before handing them off to USA to integrate. Boeing also acts as prime contractor for providing engineering expertise for the Shuttle. Lockheed constructs and delivers each external tank to the Vehicle Assembly Building for mating with the Shuttle during vehicle assembly (USA). ATK receives, refurbishes, and refuels the solid rocket boosters in Utah

before shipping them back to Kennedy where they are delivered to USA personnel in the Rotation Processing and Storage Facility. All facilities are within close proximity and many have either specialized vehicles or physical infrastructure between them to transport the artifacts of the processes in one facility to another. The legal arrangements between NASA and the contractors and between the contractors themselves are structured in great detail. NASA itself keeps a small number of its own personnel in the loop for most activities only in order to maintain some degree of institutional expertise. However, Kennedy Space Center is, in effect, a Modular Consortium on a very large scale with NASA as its host organization.

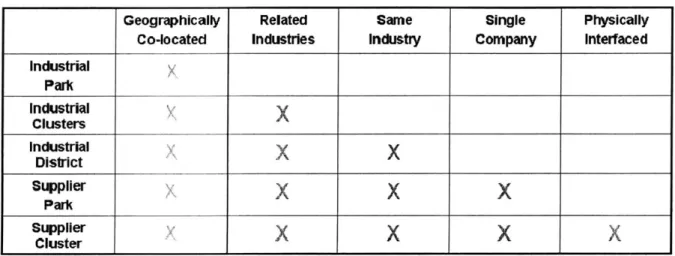

Geographically Related Same Single Physically

Co-located Industries Industry Company Interfaced

Industrial Park Industrial

X

Clusters IndustrialX

X

District SupplierX

X

X

X

Park SupplierX

X

X

ClusterX

X

Figure 2: Industrial Conglomeration Attributes

Conglomeration Development and Risks

Our research suggests different roles for firms, government, unions and trade associations in the creation and development of Industrial Conglomerations. In particular governments should avoid unilaterally specifying and setting the conditions for the creation of a

conglomeration. Instead conglomerations, of any type, should result from the emergent behavior of firms to optimize operational and strategic efficiency. Once a conglomeration has begun and is recognizable as such, it then behooves government organizations to assist in the upgrading of the conglomeration through infrastructure development, regulatory relaxation, local academic development or expansion, and worker training programs. The evolutionary concept is similar in quality to crystal formation. A conglomeration will start with a small number of firms choosing to locate in close proximity to each other to exploit some potentially resulting competitive advantage or a local geography (waterways) or infrastructure (nexus of transportation modes such as airports, train stations and highways)

feature. As the competitive advantage becomes publicly apparent through the success of the pioneering firms, other firms will seek to exploit and expand the same advantages. The inception is the formation of the seed crystal in the analogy, while secondary and continuing development is akin to the expanding growth of the crystal. Once a sufficient level of

development has occurred appropriate government action is easier to identify (versus well-intentioned yet ultimately detrimental action).

The rationale behind the various stakeholders assuming different roles is associated with risk. One aspect of the risk involved is predicting the innovation roadmap. Firms interacting with each other, exchanging goods, services, information, people and technology have a better chance of identifying innovations with high probabilities for success than

governments do. Government investment in a conglomeration based on an unproven

innovation roadmap or a roadmap unproven in a given geographic or environmental context run the risk of forfeiting investment funds in the likelier event of failure. Another aspect of risk is the rigidities necessarily created when government intervenes in competition or by action induces companies to "persist in old behaviors and relationships that no longer contribute to competitive advantage." 261 Further, government protection, early in development, can encourage premature vertical integration and blunt innovation which retards conglomeration development. Instead of restrictions on conglomeration location, subsidies, or regulatory advantages, governments should focus early conglomeration policies on developing inter-regional or inter-country trade and academic development.

Spill-over Effects of an Industrial Conglomeration

In addition to careful consideration of risks, it is also important that consideration is given to spill-over effects. Spill-over effects are the impacts that an industrial conglomeration can have on the surrounding area and populous. These effects can have many forms. Of national significance, it is common for "clusters to be a driving force in increasing exports" and they can become "magnets for attracting foreign investments" E2 7 . Likewise, an the investigation of Italian Industrial Districts found that through the evolution of efficient industrial districts, "economic dynamism coexisted with stalemated and polarized politics"[1]. In other words, despite a dysfunctional and paralyzed political system, the local economy managed to develop and flourish anyway. The spill-over effects can have the potential to compensate for major structure issues at even the national level.

In addition, spill-over effects can have great "local" impact, raising the average wage rates in an area, increasing the quality of local education, creating informal networks that aid in developing management talent and generally increasing the competitiveness of individual companies. These spill-over effects, while real and measurable, are not typically part of the operational decision making process for any given company. Additionally, it is impossible for these spill-over effects to be created by one company, acting alone.

We point out that these effects specifically spill over from the industrial conglomeration to the surrounding community and not the other way around. There are synergistic benefits available if a community and/or its government choose to promote the industrial

conglomeration by investing its own funds in infrastructure and other developments

beneficial to the conglomeration. However, we remind the reader of our earlier conclusions that governments and communities should begin significant financial investment only after a conglomeration has begun to form and take shape. Our research leads us to believe this assures a natural development of the conglomeration in response to the competitive landscape, keeping the characteristics of the conglomeration competitive. But it also reduces the risk of a community losing their infrastructure investment should the conglomeration not mature to its full potential.

It is for reasons such as these, that the presence of industrial conglomerations and the associated spill-over effects should be characterized as public goods. As such, it is important that conglomerations are nurtured by public policy in a manner that is consistent with encouraging their formation while allowing competitive pressures to shape their location, scope, size, and participants.

Virtual versus Vertical Integration

A company achieves vertical integration when it has direct control over the production of the inputs for its primary product. The further up-stream a firm controls the production of inputs, the more vertically integrated it is. The generally accepted height of vertical

integration is Henry Ford's River Rouge plant which actually received iron ore and rubber as inputs and produced automobiles as an output. Ford's plant and employees handled all processing of these input materials.

Cisco Systems represents virtual integration in the same sort of extreme that the River Rouge plant represents vertical integration. Cisco focuses on designing new products and

selling them to customers. Manufacturing, supply chain management, final assembly, and distribution are all contracted out to partners. Cisco rarely sees the products its customers receive.

The concept of virtual integration is treating a select group of suppliers as if they are very close business partners, almost as if they are inside the company. A firm seeks to outsource non-core competencies to trusted suppliers while focusing its in-house efforts on

competencies that are critical competitive advantages. This degree of close cooperation allows a high level of collaboration on product, process, and market problems while insulating the host organization from the cost burden associated with producing the input components itself. Should the market for a firms products shrink, the firm is now not responsible for carrying the fixed and variable costs associated with the business of producing the input components for its primary product (and in the case of Cisco is insulated from even the costs associated with final assembly). According to Michael

Hammer[3 9

1, the key to virtual integration is to get all participants to work together as smoothly as they would if they all belonged to the same enterprise. Good communication mechanisms must be in place to achieve this smoothness.

One aspect of Virtual Integration's relevance to Industrial Conglomerations is clear: the outsourcing of non-core competency activities. However, it is to the Michael Hammer's point, mentioned above, that the chief synergy between Virtual Integration and Industrial Conglomerations occurs. Smooth inter-corporate operations are better achieved if the players are located within close geographic proximity of each other. As discussed in other parts of this thesis, close proximity makes high bandwidth communication and problem solving more convenient, reduces some operational costs (associated with WIP, Lead Times, and Quality), and develops trust which speeds inter-firm decision making. If a firm is

considering Virtual Integration an Industrial Conglomeration may help the firm extract the most value possible.

Supplier City Concept Detail

Purpose

An army marches on its stomach. - Napoleon Bonaparte

geographic proximity to the host in order to improve the supply chain and logistics

performance of the overall enterprise. By co-locating, the suppliers can share infrastructure and resource costs and develop cooperative support mechanisms. The host company can develop stronger relationships with key suppliers, increase data sharing, cooperation on problem identification, and resolution, and pursue shared cost reduction initiatives. Typical supply chain optimization too often focuses on locally optimizing a single organization or process. In contrast, a Supplier City, by bringing participants closer together and fostering trust, and more directly, cooperative relationships, can broaden the scope of optimization to include many organizations across multiple layers of the supply chain.

A Supplier City moves an organization closer to virtual vertical integration versus corporate vertical integration. This transition enables the organization to focus on its core

competencies and leverage those of its suppliers thereby reducing cost, increasing quality, and increasing enterprise responsiveness. In this way, an organization can push the cost-quality pareto front while focusing on areas where it truly provides value for its customers.

Description of a Supplier City

Key Benefits

Supplier Cities provide a set of key benefits to both the host and participants critical to the value proposition. In fact, Supplier Cities provide a large set of primary, directly measurable as well as secondary, indirect benefits. The secondary benefits tend to create virtuous cycles among different sets of stakeholders and value generation is measurable if not precisely quantifiable. For example, investing in a local supply base through a Supplier City may create secondary investment effects such as attracting talent and outside investment to the area. This will eventually develop the concentration of talent, potential partners, industry capability, and availability of capital in the environment surrounding the host and Supplier City. Primary benefits focus on the more immediate impacts of a Supplier City on supply chain and logistics metrics including cost, schedule, responsiveness, and exposure to business risk. The complete set of benefits create a direct and near-term improvement in enterprise value returned and set in motion a system of business environment development to pay dividends over the long term.

Lead Time Reduction

By locating suppliers close to the host, lead times are greatly reduced. This reduction in lead time is achieved several ways. The bulk of this reduction occurs through greatly reduced shipping times. In the most dramatic cases, long ocean voyages, passages through customs, and multiple vehicle hand-offs may be completely eliminated. Shipment is as simple as loading up a single ground transport vehicle in the Supplier City, driving it the short distance to the host, and unloading it. Physically integrating a supplier with the Host can even eliminate the transport vehicle.

The degree of lead time reduction achieved is a function of the supplier's ability to maintain, through inventory or short cycle time production capacity, the ability to deliver parts shortly after they are ordered. Simplifying and shortening the shipping process is only part of lead-time reduction. More generally, lead lead-time reduction depends on the degree to which factors chiefly responsible for long lead times are eliminated from the supply chain and not just

moved one or two steps away from the host. For example, if a host invited a supplier to Supplier City in order to eliminate its dependency on a complex or lengthy overseas sourcing strategy, but the supplier has a similar dependency for parts or components used in its production of components for the host, then the degree of lead time reduction will be limited and possibly even negated.

Faster quality cycles and lower costs are the chief benefits of reducing lead time. Shorter lead-times and closer distances means less inventory not involved in value added steps (e.g.: machining, assembly) freeing up capital. Components may also cost less due to cheaper shipping fees. Quality problems may be discovered and dealt with more quickly and effectively if the supplier is located close by. Lead-time reduction has the potential of

moving a host firm further out into the cost-quality frontier, giving it a competitive advantage.

Holding Cost and Storage Space Savings

If the host organization is using a formal Economic Order Quantity model to calculate its order quantities and order intervals, lead-time reduction will result in a reduction in on-site inventory of component parts. A shorter lead time and cheaper shipping costs (due to supplier proximity to the host site) mean components may be ordered in smaller quantities, more frequently, and closer to the time of actual usage in the host's production process. This transition to a more just-in-time supply methodology lowers the inventory levels at the

host's site which translates directly to lower annual holding costs, freeing up capital for other purposes. It can also lead to reduced inventories at the supplier facility which reduces the total capital tied up in the enterprise. The additional space made available by the

reduction in inventory may also be re-purposed for value generating activities. Other holding cost reductions come from the reduction or elimination of the physical inventory process and the reduction or re-purposing of some fraction of the procurement personnel.

Shared Infrastructure Costs

Co-locating multiple suppliers enables them to cooperatively share common resources and reduce operating costs, sharing the value created with the host. By sharing capital

equipment, warehousing facilities, and delivery vehicles, suppliers can dramatically reduce their overall cost of operations. The limits to this sort of infrastructure sharing are

dependent on the degree of commonality in the infrastructure requirements of each organization, the degree to which each organization needs to protect proprietary

information, and each organization's ability to develop cooperative relationships with the host and other suppliers. During the planning phases, the host should develop a sensible cooperative sharing profile for the Supplier City that takes into account the balance between the expected infrastructure commonality (including shipping requirements) and protection of

proprietary information for the set of components to be supported. The host may then use this profile to prepare a Supplier City infrastructure attractive to potential participants as a standard for supplier selection and as an ideal target for continuous cost reduction and

improvement of the Supplier City over time. By understanding the possibilities for shared infrastructure costs, incorporating them practically into the infrastructure development, and soliciting participation by suppliers interested and able to function in a cooperative

environment, the host's holding cost savings can be enhanced by lower component prices across the board.

Quality Control

The host can use its close, cooperative relationships to the suppliers in Supplier City to improve the quality and consistency of components delivered to its production facilities further enhancing cost savings associated with supplier quality improvement. To do this, the host uses the relationship to develop an enterprise wide culture and policy of conducting root cause analysis of quality problems proximal in time, location and people to the

problems' occurrence. The involved personnel, including individuals from both the supplier and the host, then re-engineer the process that generated the defect to reduce or eliminate

defect occurrence. The benefit of a Supplier City to Quality control is realized through proximity. Information has a half-life. Root cause analysis is made more effective the sooner the problem is attacked, the closer the solvers are to the place of occurrence, and the more completely represented all the directly affected stakeholders are. Having a supplier across the street versus across the country, or even across town, means quality problems discovered by the host in a supplier's delivered component may be more quickly attacked, at the point of occurrence, by both the customer and the supplier in a cooperative root cause analysis. Such a system of consistent and immediate root-cause analysis and process re-engineering by the operators, engineers, and managers directly involved, from both the supplier and the host, yields continuously improving component quality, reduces the enterprise's dependency on inspection and rework, and enhances the host's cost competitiveness in the medium to long run.

Quick Response

To successfully handle the volatile nature and unexpected opportunities of an evolving and developing market, an organization must ensure its supply system can support its target level of flexibility. Supplier City groups key suppliers together locally where relationships can be developed to create a more team oriented system with common goals, interests, and understandings. By engendering trust, transparency and cooperation beyond that of

geographically dispersed stakeholders, a Supplier City allows product, design, and process decisions that affect host and supplier alike to be taken on a much shorter time scale. This is because less travel is involved, more high-bandwidth communication can occur through convenient face-to-face encounters and a common language that develops over time, and less legal wrangling ensues as each player seeks to protect itself. Another source of flexibility comes from the convenience of impromptu meetings between the host and

suppliers to discuss how internal or external developments may be addressed to the benefit of all. This one-for-all culture, when coupled with short delivery times and the ability to quickly connect physically for problem identification and resolution, creates an overall system capable of responding quickly to changes in external factors. These unexpected external changes can include regulatory, environmental, community, and customer

requirements. Developing an understanding of the likely risks enables the host and suppliers to proactively tailor, by design, the Supplier City's quick response capability, further

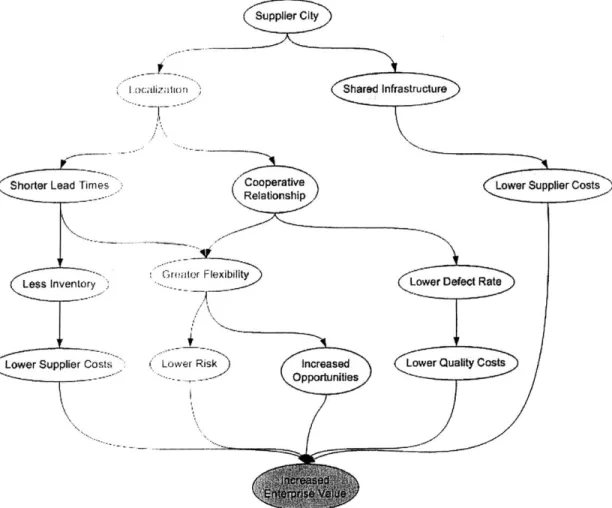

Value Cascade

The following diagram illustrates the cascading value of a Supplier City. Beginning with a Supplier City, value flows down through a variety of mechanisms and processes such as Shared Infrastructure, Shorter Lead Times, and Risk Mitigation to result in overall increased enterprise value. Some entities are directly measurable benefits while other, less directly

measurable, benefits result from the creation of virtuous cycles in the system.

Ioca? ion Shared Infrastructure

Shorter Lead Tines Cooperative (Relationship

v r rtr Flexibiflity Lower Defect Rate

Lower Supplier Costs I Lwer Risk) Increased Lower Quality Costs

Opportunities

Figure 3: Potential Value Flow-down Pathways

Location and Geography

In determining the geographic parameters for a Supplier City, it is important to consider the economic, regulatory, community, and infrastructure attributes of the candidate locations as well as their available expansion-avenues. The tax situation of different locations can impact the value of conducting supplier activity. Special economic zones may exist in some

locations but not others, or government authorities may be interested in creating one to support a Supplier City development. The amount of space available will determine the number and size of suppliers the Supplier City can host. Of related importance are the specific activities of each supplier: manufacturing may require more space or be subject to

more economic or environmental regulations than a warehouse style Supplier City. If there is a surrounding or nearby community, evaluating their needs early can help avoid litigious or political difficulties later. Future physical expansion of the Supplier City should also be considered to ensure future requirements for space, possibly for additional suppliers, can be met. This may indicate locating adjacent to open space owned by a cooperative agent or even purchasing an option on open space. Finally, proximity to supporting infrastructure

and services such as utilities, emergency management services, second tier suppliers, etc. can improve the value proposition of the Suppler City.

Supply Network

In addition to improving operational efficiency and product quality, lowering costs, and increasing flexibility a Supplier City can also reduce or mitigate certain risks present in an organization's supply network. However, to effectively realize this benefit, it is important that the selection of Supplier City participants includes only suppliers with less exposure to the most significant risks. One example is shipping risk. Distant suppliers have greater shipping costs; longer shipping times, and are exposed to increased risk of loss, damage, theft, or delay. To the extent a local supplier uses different sources for its materials; it can

reduce or eliminate these risks for the host. The upstream supplier network may differ in being all local or may include distant upstream suppliers located in regions carrying less shipping risk than the host's original supplier network. Another example is avoiding negative regulatory impacts. Depending on the differences between the relative regulatory

environments of local vs. distant suppliers, the host may be able to eliminate the regulatory risk of sourcing from a distant supplier by localizing.

Chapter 3: Strategic Issues

The evaluation of a Supplier City needs to begin with an understanding of key issues that will guide and shape important decisions. In our research, we found seven concepts critical to understanding the decision making process for any company investigating such an

implementation. In our work, we uncovered and examined these concepts by first looking at the imbedded assumptions in our host organization. These exercises allowed us to challenge the assumption, verify or refute the underlying reasoning and science as well as develop structured explanations of the strategic issues. It is important for us to review them here, because they build the foundation for our evaluation and development

framework.

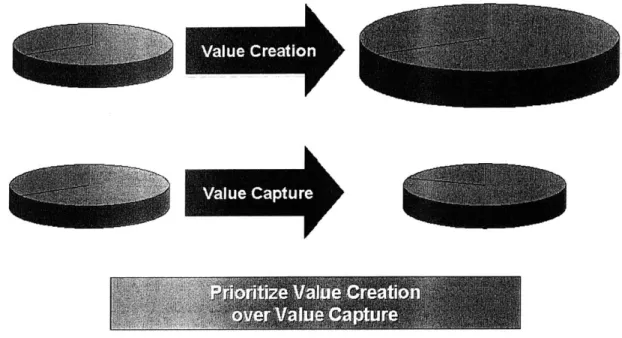

Value Creation vs. Value Capture

In our investigation and discussion of the Supplier City concept we made the discovery that most people fixate on the "how" of the relationship. How do we structure the relationship? How do we share investment and later profits? How do we manage intellectual property?

All of these issues are secondary to that of Value Creation through the relationship. In order for a Supplier City to really work, the Host and its participating suppliers must forge a genuine partnership based in trust and mutual development and benefit. If the amount of enterprise value does not grow as a result of the relationship (Value Creation), the various parties may get bogged down with the struggle to claim a greater share of the available value (Value Capture). Value Creation is the phenomenon associated with

increasing the Potential Industry Earnings (PIE - see Figure 4), where Value Capture is the activity focused on distributing the PIE to various stakeholders. Value Capture centered

behavior will ultimately degrade the utility of a Supplier City. The primary focus of a Supplier City should be to grow the available enterprise value and thus, all considerations for creating and developing a Supplier City should begin with the issue of value creation. Once accomplished and before actually implementing the Supplier City, or any additional phased developments, the partners should then build constructs to ensure a fair and satisfactory degree of value capture for each relevant party. If Value is created with each additional development everyone may benefit from the Value Capture arrangement.

MU.W

qr

Value JCapture

Figure 4: This figure highlights, visually, the difference between Value

Creation and Value Capture. Companies that focus on creating value to be

shared among all partners create more collaborative relationships than

those that focus on capturing a larger portion of the existing value.

Marginal Benefit vs. Marginal Cost

A commonly held bias in business is that bigger is better. This bias surfaces in many different ways and it can have an impact on the decisions facing a company implementing or investigating the development of an industrial conglomeration. Each decision to add another process, another partner, and greater complexity needs to be made in the best interest of the company and the Supplier City.

An underlying concept of economic decision making is ensuring that any expansion in the business's activities should yield at least as much value as the cost required to implement the expansion; that is, Marginal Benefit minus Marginal Cost, the marginal increase in total benefit associated with the addition of a supplier or process minus the cost associated with those same additions should be positive. Figure 5 shows the total cost associated with the nth supplier (yellow bars) overlaid on the total benefit or value of the same implementation (orange bars). In this illustration, for the third supplier the change in value is greater than the change in associated cost. However for the seventh supplier the change in value is not great enough to compensate for the additional costs. Applied to the Supplier City concept,