Metaphorical Display of Moods and Ideas

in Picture Books

Isabelle Gras – CLIMAS, Université Bordeaux Montaigne

Abstract

In picture books, metaphor can be expressed through the text, through the image or through both. The first way develops verbal metaphors while the other two create pictorial metaphors. According to Doonan in Looking at

Pictures in Picture Books, images have two basic modes of external reference: denotation and exemplification.

Drawing on her conception of exemplification as a means to express abstract notions, conditions or ideas, this article contends that moods, eccentric ideas or philosophical reflections can be metaphorically displayed in images, and that the processes involved work at different levels of meaning.

Three picture books were selected for this purpose: The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish, written by Neil Gaiman and illustrated by Dave McKean; Rules of Summer, by Shaun Tan; and The Invention

of Hugo Cabret, by Brian Selznick. In each one, images or sequences are analyzed, following Painter’s,

Martin’s and Unsworth’s systemic-functional approach to visual narratives in Reading Visual Narratives. This shows that the processes involved in metaphorical display work at different levels of meaning, rooted in Halliday’s metafunctions of language, and that they all contribute to revealing the underlying metaphor. Whereas McKean’s pictorial processes allow him to evoke the complex mood of the main character, Tan’s images interact with the text to suggest metaphorical interpretations of conflictual conceptions of the world, and Selznick’s specific type of relationship between text and image offers him the opportunity to develop a cinematographic metaphor throughout his narrative.

Keywords

24

Résumé

Dans les albums, la métaphore peut être exprimée par le texte, par l’image ou par les deux. Alors que le premier génère des métaphores verbales, les deux autres développent des métaphores picturales. Dans Looking at

Pictures in Picture Books, Doonan considère qu’il existe deux modes de base permettant à l’image de faire

référence à quelque chose : la dénotation et l’exemplification. Partant de sa conception de l’exemplification comme moyen d’exprimer des circonstances, des idées ou des notions abstraites, cet article soutient que l’image permet la représentation métaphorique d’idées excentriques, de réflexions philosophiques ou d’humeurs, et que les procédés utilisés fonctionnent à différents niveaux de sens.

Trois albums ont été sélectionnés pour cela : The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish, écrit par Neil Gaiman et illustré par Dave McKean, Rules of Summer, de Shaun Tan, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, de Brian Selznick. Des images ou des séquences extraites de ces ouvrages font l’objet d’une analyse fondée sur l’approche systémique-fonctionnelle des narrations visuelles élaborée par Painter, Martin et Unsworth. Ceci montre que les procédés utilisés dans la représentation métaphorique fonctionnent à différents niveaux de sens, ancrés dans les métafonctions du langage définies par Halliday, et qu’ils contribuent tous à révéler la métaphore sous-jacente. Alors que les procédés picturaux de McKean lui permettent d’évoquer l’humeur complexe de son personnage principal, les images de Tan interagissent avec le texte pour suggérer des interprétations métaphoriques de deux conceptions conflictuelles du monde, et le type particulier de relation texte-image choisi par Selznick lui offre la possibilité de développer une métaphore cinématographique à travers toute sa narration.

Mots-clés

Introduction

As picture books developed in the 20th century, children’s literature scholars identified the relationship between text and image as a major component of the dynamics of this specific medium. Many approaches were elaborated to describe this relationship, based on analogical thinking, theoretical constructs, phenomenological studies of children’s responses to picture books and typologies (Sipe). Analogical thinking borrows metaphors from the arts or other domains. While Sendak resorts to musical terms to describe the interaction between text and image in Caldecott’s picture books (Sendak 21), Lewis uses the extended metaphor of the picture book as an ecosystem, to account for the change in relationships between text and image from one double page to the next (Lewis 48). Theoretical approaches develop concepts such as “limiting”, suggested by Nodelman, whereby “the words limit the pictures, just as the pictures, simultaneously act to limit the words” (Sipe 10). Kümmerling-Meibauer applies Iser’s concept of indeterminacies to picture books, to account for the fact that the information missing from the text can be supplied by the images (Kümmerling-Meibauer). Lewis points out the limitations of the typologies, questioning the appropriateness of categories to define an interaction of pictures and words that changes from one double page to the next (Lewis 39–40).

Bateman remarks that the relationship between text and image in communication artefacts has often been analyzed in terms of metaphor (Bateman 175). Forceville developed a model for pictorial or visual metaphors in advertisements (Forceville, Pictorial Metaphor in Advertising), and scholars have started studying metaphors in a wide variety of images, like comics (Eerden), political cartoons (El Refaie) and cinema (Fahlenbrach). Picture book scholars such as Schwarcz and Doonan also noted the role played by metaphor in text-image relationships. Drawing on Doonan’s conception of exemplification as a means to express abstract notions, conditions or ideas, this article contends that moods, eccentric ideas or philosophical reflections can be metaphorically displayed in images, and that the processes involved work at different levels of meaning.

Three picture books were selected for this purpose: The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish, written by Neil Gaiman and illustrated by Dave McKean; Rules of Summer, written and illustrated by Shaun Tan; and

The Invention of Hugo Cabret, written and illustrated by Brian Selznick.

The first part will present Schwarcz’s conception of pictorial metaphor as a potential representation of written metaphor, and compare it with Doonan’s notion of metaphorical evocation through pictorial processes. These processes will be identified according to the systemic-functional approach to visual narratives developed by Painter, Martin and Unsworth.

The three following parts will be devoted to the analysis of images and sequences in the picture books above mentioned in order to study how the pictorial processes contribute to evoking abstract aspects of the texts.

1. Metaphorical evocation in picture books

Scholars have often acknowledged the presence of metaphor, especially pictorial metaphor, in picture books, but only a few have attempted to analyze it. In picture books, metaphor can be expressed through the

26 text, through the image, or through both. The first way develops verbal metaphors while the other two create pictorial metaphors.

Attempting to describe the different types of relationship between text and image, Schwarcz studied the challenge offered by metaphorical language to the illustrator. He considered that illustrating a text was a way to interpret it, and observed four possibilities to represent a verbal metaphor: realistic representation; literal representation; evocation of the mood of the verbal image; and transformation of the verbal metaphor into a visual metaphor (Schwarcz 36–51). In the realistic representation, the illustrator may “ignore the metaphorical component in the text on hand and concentrate on other parts”, and the metaphor is presented “without any visual reference to its figurative intention” (Schwarcz 36). Schwarcz gives the example of objects that are personified in a text but depicted as functional objects. The literal representation of metaphor depicts the target and the source of the metaphor in a denotative, descriptive way which often results in an absurd or comical effect. Schwarcz considers that “it treats the metaphor as if it were a riddle with a single solution to it” (Schwarcz 50). By contrast, the transformation of the verbal metaphor or the evocation of the mood of the verbal image allow illustrations to function as “analogues of the verbal image”, using their own elements to transform the verbal metaphor into a visual one (Schwarcz 51). The evocation of the mood of the verbal image contained in the metaphor is achieved “[w]hen the illustrator succeeds in creating a picture which somehow resounds with the mood that gave rise to the metaphor in the first place, even without rendering the verbal image at all” (Schwarcz 51). In the examples he provides, Schwarcz shows how colour, the spatial organization of depicted characters or objects, or certain types of layout contribute to creating the mood developed by the verbal metaphor.

Doonan extends the possibility of metaphorical evocation in images beyond the expression of mood. She underlines that “[p]ictures have two basic modes of referring to things outside themselves: denotation and exemplification” (Doonan 15). Denotation represents the literal, explicit meaning of a word. Hence, a literal depiction of an object includes the features that allow us to identify it but does not depend upon physical likeness. According to Ricœur, denotation is a way of referring to a thing by way of a symbol, whereas exemplification refers to a symbol by way of a thing (Ricœur 295). An object painted in a certain colour provides an example of that colour. The colour can also be said to refer to the object, and so to denote it. Doonan extends the idea of exemplification to the way “pictures show, by example, abstract notions, conditions, ideas, that cannot be pointed to directly but may be recognized through qualities or properties which the pictures literally or metaphorically display” (Doonan 15). She highlights the expressive roles of colour and settings in the suggestion of mood (Doonan 40) and of margins in the expression of ideas: “In Where the Wild Things Are Sendak chose to mirror the escalating scale of Max’s psychological rage and rumpus by gradually increasing the size of the pictures in a succession of twelve page openings” (Doonan 17).

1.2 A systemic-functional approach to visual narratives

These features and many others, specific to visual narratives, were identified and organized into systems by Painter, Martin and Unsworth, following a systemic-functional approach (Painter, Martin, and Unsworth). Drawing on Kress and Van Leeuwen, Painter, Martin and Unsworth consider that the systemic-functional approach to language developed by Halliday can be extended to other semiotic modes, particularly the pictorial

mode. Kress and Van Leeuwen show that the three metafunctions of language, which constitute the basic tenets of Halliday’s theory, can be found in any semiotic mode.

The ideational metafunction is concerned with representing aspects of the world as it is experienced by humans. In the visual mode, this metafunction includes the representation of objects (characters or settings), their relations to other objects, and processes (actions and reactions). Actions such as speaking or thinking are typically represented in comics by speech or thought bubbles, processes that can also be found in picture books, as we will see in the second part of this study.

The interpersonal metafunction accounts for the representation of the relations between the author or illustrator, the reader or viewer, and the object represented. In images, the interpersonal metafunction operates through choices of style of representation, number of elements, size, colours, or focalization. Through processes of zooming in and out, focalization guides the reader’s gaze in the image, while colour and size single out elements that require interpretation.

Finally, the textual metafunction is concerned with the compositional organization of a page or a double page, and involves choices in the relative positions of focus groups – which in this article mean groups of represented elements – choices in layout, and in framing. By separating images, frames highlight their fictionality; framing can also determine a specific literary genre, such as comics, or a particular art, like early cinema.

2. Moods and ideas

2.1 The hero’s feelingsIn The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish, written by Neil Gaiman and illustrated by Dave McKean, the first page of the narration presents an integrated layout with three focus groups – two texts and a drawing – sharing the same background. The position of the two texts, at the top and at the bottom of the page, leaves the drawing between them. The story is told by a first-person singular narrator, the boy who is the hero of the picture book. His voice first introduces his dad in a neutral way: “One day my mum went out and left me at home with just my little sister and my dad”, and then hints elliptically at his father’s lack of concern for his children: “My dad sat in front of the television, reading his newspaper. My dad doesn’t pay much attention to anything, when he’s reading his newspaper” (Gaiman and McKean unpaged). Limited by the two texts, the picture of the father represents him as caught in between the narrating boy’s words. The layout thus contributes to developing the boy’s disapproval of his father’s indifference toward his children.

The first-person singular narrator unambiguously establishes the boy as the focalizer on this page and invites the reader/viewer to see the depicted father through his son’s eyes. This is confirmed by the fish inserted at the top of the father’s chair, hinting at the upcoming swapping of the father for goldfish. The metonymic representation of the father, whose upper body and head are hidden by an open newspaper, does not allow the reader/viewer to develop empathy with the character. It thus creates an alienating effect which supports the narrator’s opinion. Since the father is recurrently depicted as a newspaper with legs throughout the book, this representation becomes a metaphor of him. This type of metaphor constitutes what Forceville

28 defines as a hybrid metaphor, where the target – the father – and the source – the newspaper – are depicted in a single gestalt1 (Forceville, “Pictorial and Multimodal Metaphor”).

McKean’s mixed technique – blending collages of recycled pieces of newspaper, graph paper and photographs showing under translucent ink drawing and painting – establishes the materiality of the image as a creative item as opposed to a reproduction of reality. Douglas considers the layers of McKean’s images as layers of meaning. « L’œuvre fonctionne comme un palimpseste : elle dévoile peu à peu les différentes couches de sens qui naissent des ingrédients et matériaux, marqués par leur époque, la composant. » (Douglas 144) In this image, the complex texture uses real materials to question reality – changing the direction of the newspaper lines or blurring the collages digitally, for example – thus creating a fictional world, and developing a modal aspect. While the layout, the type of focalization and the relative size of elements of the image metaphorically evoke the narrator’s disapproval of his father’s lack of concern for his children, the texture of the image blurs the boundary between reality and fiction, and evokes Gaiman’s and McKean’s specific atmosphere of fantasy.

1 An organized whole that is perceived as more than the sum of its parts.

Figure 1. “First page”

The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish (unpaged)

Text copyright © Neil Gaiman 1997. New material copyright © Neil Gaiman 2004. Illustrations copyright © Dave McKean 1997. New material copyright © Dave McKean 2004.

2.2 Breaking the codes

The boy’s disapproval of his father’s attitude and of the codes of adults is also evoked by the breaking of codes in the picture book. Gaiman’s narration breaks the literary codes by integrating features from different genres. The story borrows its structure from tale, its first person singular narrator from realistic narrative, and the obstacles that the hero must overcome from the pattern of quest.

The breaking of literary codes is mirrored by the breaking of pictorial codes. McKean breaks the code of comics by adding introductory verbs like “said Nathan” under the speech bubbles and by alternating them with the conventional use of brackets for dialogue, as can be seen in the two images below. This unconventional use of codes can also be observed in the absence of frames or a gutter around pictures including speech bubbles, and in the irregular margins.

The social codes are equally broken in the narration through the swapping of the father, discussed in terms of numbers, as Nathan says “I’ve got two goldfish, and you’ve only got one dad”, and confirmed by the alienating depiction of the father, emptied of his human substance and filled with goldfish. This hybrid metaphor illustrates the verbal simile, “He’s as big as a hundred goldfish”. Forceville, like Steen, considers

Figure 2 “That’s not a fair swap”

The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish (unpaged)

Text copyright © Neil Gaiman 1997. New material copyright © Neil Gaiman 2004. Illustrations copyright © Dave McKean 1997. New material copyright © Dave McKean 2004.

30 simile2 – whether pictorial or verbal – as a particular form of metaphor. Presenting the father in terms of goldfish, the hybrid metaphor is used by the hero as an argument to make a point. The black paint, roughly applied on the background, evokes an old traditional blackboard, while the composition of the image, neatly separating the fish-filled silhouette from the text in a white handwriting-style font by an arrow, reinforces the school context to create the metaphorical evocation of a scientific demonstration.

In this picture book, McKean’s images metaphorically display the alienation of the father through choices in depicting style, characters’ appearance, layout, organization and size of focus groups of the image. In contrast to The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish, Rules of Summer, written and illustrated by Shaun Tan, presents a series of rules with a single narrative sequence toward the end.

3. Conflicting views of the world

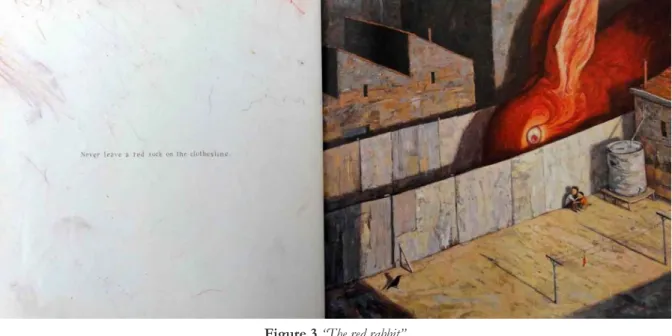

3.1 Uncontrolled feelingsBased on childhood memories, Rules of Summer develops the ambiguous relationship between two brothers – the younger still learning the social codes under the domineering gaze of the elder. On the first double page of Rules of Summer, the reader’s eye is attracted by the red rabbit whose gigantic size, vibrant red and central position make it stand out in the image. The detailed depiction of the rabbit, the nuances of light showing bodily movements under its fur, and the shades of pink inside its ear give it a realistic appearance, so that the contrast with its size and colour produces an unexpected, uncanny effect. The red rabbit’s gaze, just above the wall, creates a vector from its eye to some point in the foreground. The two boys, huddled up against the wall, the elder trying to choke his brother’s terrified sobs, are depicted in a hiding position, but the image does not provide a clue as to the presence of the rabbit. Instead, the vector created by the lines of the walls directs the reader/viewer’s gaze to the left page and the text.

The text, which reads “Never leave a red sock on the clothesline” (Tan unpaged), does not add narrative meaning to the image. It stands like an enigmatic instruction. The contrast between its benign lexical meaning and the strong grammatical meaning of its negative imperative clause structure causes the reader/viewer to question its literal meaning. The single line of text represents a vector that takes the reader/viewer’s gaze into the image, along the wall, to the rabbit’s eye, and above the wall toward the tiny, lonely red sock on the clothesline that it identified as a clue, accidentally forgotten by the children. The image thus exemplifies the connotation of the text.

This exemplification, however, remains ambiguous: what of the red rabbit? Terrifying because of its size and colour, and comforting because of its bunny shape; does it personify the emotional conflicts of the young child, still unable to control his feelings and his imagination, but trying to learn the social codes that frame the life of adults? Ambiguity constitutes an essential feature of Tan’s images as it slows down the reading process to invite multiple interpretations, as the author explained at a conference (Tan, “Words and Pictures, an Intimate Distance”).

2 “A figure of speech that expresses the resemblance of one thing to another of a different category usually introduced by as or

3.2 Imagination vs order

The metaphor is not always added through one particular character; it can also be developed by the visual context. The fourth double page of Rules of Summer exemplifies potential trespassers, hinted at by the written rule “Never leave the back door open overnight”, but the metaphorical evocation is suggested in the organization of focus groups.

The composition of the image presents four focus groups: the lizards and the red tree; the doorframe under which stand the two boys; the sea creatures; and the TV set. The groups are linked by the gazes of the characters, which form three vectors: one from the lizards to the children; a second one from the children to the sea creatures; and a third one from the sea creatures to the television set. The groups on the right-hand side of the image are contrasted with those on the left-hand side in terms of position, line and colour. The curves and shades of bright red and yellow of the intrusive creatures or plants on the right-hand side are opposed to the straight lines of muted blue of the doorframe and the television on the left-hand side.

A similar contrast opposes the two boys through their size and their attitude. While the taller, older brother lifts his eyebrows in disapproval, crossing his arms to signal that he takes no part in the invasion, the younger brother’s sinking eyebrows display his disheartened spirit, and the pail and the spade in his hands indicate that he is responsible for the presence of the trespassing creatures and has to get rid of them. Thus, the contrast between the focus groups evokes metaphorically the conflicting views of the world between the younger child, not yet able to separate the real world from his imaginary world, and his elder brother, already familiar with the codes of adults.

In Rules of Summer, Tan introduces a tension between benign lexical meaning and negative imperative clause structures, which needs exemplification in the image. This exemplification can take the form of a character or be represented by the visual context. In each case, choices in ambience, graduation, focus groups and texture question the literal meaning of what is depicted, and metaphorically evoke two contrasting conceptions of the

Figure 3 “The red rabbit”

Rules of Summer (unpaged)

32 world: the rational view of the elder brother or the irrational view of the younger one.

Our analysis has so far been limited to metaphorical evocation in one page or double page. In Brian Selznick’s books, it often develops into a sequence.

4. Cinematographic gaze

4.1 Metaphors of cinemaIn The Invention of Hugo Cabret, Selznick created a new and quite unusual format of picture book in which the narration is developed alternately by the text and the images, so that both modes take equal part in the narration. In this 533-page book, which won the Caldecott Medal in 2008, text and images are completely separated, never facing each other, each developed in series of double pages. The sequence of images that opens The Invention of Hugo Cabret starts with three double pages of the moon. The first double page presents a small image bounded by a very large black margin that focuses the reader/viewer’s gaze toward the image in the centre. This image, lit by a large moon depicted in shades of black and white dramatized by lighting effects, was compared to a screen by Selznick himself in an interview: “The first thing that you see is basically a black page with a small screen, almost like a movie theater screen that’s far away” (Norris unpaged). The metaphor of the screen is extended over the two following double pages, in which the image becomes progressively larger as if, according to Selznick, the reader/viewer was getting closer to the screen while a zooming-out process reveals some of the night sky and, on the last of the three double pages, the city of Paris.

In his Caldecott Medal acceptance speech, Selznick explains: “I wanted to create a novel that read like a movie. What if this book, which is all about the history of cinema, somehow used the language of cinema to tell its story?” (Selznick, “Caldecott Medal Acceptance” unpaged) So the black double page, the bright

Figure 4 “The back door”

Rules of Summer (unpaged)

rectangle image in the centre, the zooming-out process were all selected by the author for their metaphorical evocation of cinema.

Similar processes are used to bring the narration to its end, in a six double-page sequence of images. The first of these double pages displays the image of the moon that opens the story, but on a much larger scale, and bounded by a thin black margin. The wide size of the moon creates a sharp contrast between the bright grey and white shades that cover it, and the darker areas of night sky around it. The five following double pages show the image gradually decreasing in size until it reaches the format that opens the narration. As the black margin becomes conversely larger, the bright disc of the moon progressively disappears in the night sky. In this literal depiction of the lunar phases, the bright disc of the moon is reminiscent of an old movie projector whose light is switched off at the end of the film.

Figures 5, 6, 7 “The moon: starting sequence”

The Invention of Hugo Cabret (4–5; 6–7; 8–9) Copyright © Brian Selznick 2007. Used by permission of the artist.

34

4.2 Cinematographic processes

The depiction of the moon is not the only process to evoke cinema. The zooming-out process that introduces the reader/viewer to the city of Paris by night gives way to a zooming-in movement as the main focus group of three successive images becomes the train station, whose size increases gradually until we enter it, following the character next to its open door.

Inside the station, in a crowd of anonymous characters mostly depicted with their backs toward the viewer, the hero is singled out by a halo of light, reminiscent of the light of a projector. The position of his body, leaning slightly forward, shows that he is walking, inviting the viewer to follow him. The next double page reveals a metonymic portrait of him in a very close shot. According to Painter, Martin and Unsworth, this type of picture invites the reader into the story while providing insight into the character’s intention. In the absence

Figures 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 “The moon: ending sequence”

The Invention of Hugo Cabret (512–513; 514–515; 516–517; 518–519; 520–521; 522–523) Copyright © Brian Selznick 2007. Used by permission of the artist.

Figure 14, 15, 16 “The train station”

The Invention of Hugo Cabret (10–11; 12–13; 14–15) Copyright © Brian Selznick 2007. Used by permission of the artist.

of visual context, Hugo’s glance over his shoulder fulfils a double function. The pupil in the corner of his eye could be checking for unwanted followers, as in a suspense movie, or making eye contact with the spectator. As the zooming-in process takes the viewer ever closer to Hugo, the black margin surrounding the image diminishes to reach the size of a black frame around Hugo’s portrait. This black margin frames every double page of the book, text and image alike, in a process reminiscent of the black frame that can be found in some old black and white movies.

Another process borrowed from cinema consists in the frequent changes in the angle of view by zooming in or out. A medium long shot allows the viewer to follow Hugo up a staircase, contrary to the passengers all going downstairs, and a zooming-out process in the next image displays the hero running across the entire train platform.

Figure 17, 18 “Inside the train station” and “Discovering Hugo’s face”

The Invention of Hugo Cabret (16–17; 18–19) Copyright © Brian Selznick 2007. Used by permission of the artist.

Figure 19, 20 “Up the stairs” and “Across the platform”

The Invention of Hugo Cabret (20–21; 22–23) Copyright © Brian Selznick 2007. Used by permission of the artist.

36 Then another zooming-in process takes us closer to the hero again as he leaves the crowded areas of the station to reach a dark hallway. His glance over his shoulder forms a vector directed toward possible followers beyond the frame, and his hand on the wide arch that opens the hallway shows that he keeps as close as possible to the wall, perhaps to hide in a corner, if necessary. This is confirmed in the following double page which displays Hugo leaning against a wall, in the middle of the hallway, in a medium shot that reveals his sideway gaze, checking again for unwanted followers.

The suspense developed by the boy’s hiding stance increases as a close shot takes the viewer to an air vent that he is trying to open from the side. The metonymic view of the boy, positioned in the left upper corner of the image, hides most of his face, while his arm covers his mouth, thus focusing the viewer’s gaze on his wide open left eye, staring backward in an expression of fear. His arm, extended toward the air vent, connects the two focus groups of this image. Hugo’s hand on the slightly open air vent suggests some hiding place, confirming the necessity of secrecy implied by the frequent glances over his shoulder to check for unwanted followers. The suspense comes to a climax in the very close shot that reveals a foot disappearing into the air vent. The metonymic representation hides the identity of the protagonist, which adds a dramatizing effect to the depicted action. However, the visual context of the sequence allows the viewer to identify the foot as Hugo’s, just as the metonymic shots in a film on a character’s hands or legs allow the spectator to identify the person.

Figure 21, 22 “The hallway”

The Invention of Hugo Cabret (24–25; 26–27) Copyright © Brian Selznick 2007. Used by permission of the artist.

So, the changes in the angle of view – with very close shots revealing unexpected metonymic views of the hero and his environment, contrasted with medium shots or long shots to represent action in sequences of images – together with the use of black frames around the images are all processes borrowed from cinema, generating throughout the picture book the metaphorical evocation of a film.

Conclusion

Pictorial metaphor, defined as a metaphor completely or partly developed by the image, offers a different way to analyze the relationships between text and image. Schwarcz and Doonan showed how specific processes of the image could contribute to the metaphorical evocation of abstract aspects of the text. Painter, Martin and Unsworth’s systemic-functional approach to visual narratives provides a detailed account of visual meaning examined in terms of construction of narrative events and characters, visual positioning of the reader, and organization of visual and verbal meanings on the page or the double page.

In The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish, McKean breaks the social and pictorial codes through hybrid metaphors whose ideational meaning is amplified by interpersonal and textual meaning through a scrapbook aesthetics and borrowings from other genres such as comics. In contrast, Tan mostly resorts to metaphorical evocation in Rules of Summer through interpersonal and textual choices in colour, size and visual composition, which highlight the tension between two brothers in their private universe of play and imagination. In Selznick’s The Invention of Hugo Cabret, the metaphors of the page as a screen or of the moon as a projector, and the frequent changes in the angle of view in sequences of images to represent action, develop ideational, interpersonal and textual meaning to create the metaphorical evocation of a film.

These three picture books present different types of pictorial metaphors, some of them depicted by ideational elements, others implied by interpersonal or textual processes. However, as the systemic-functional approach used in this paper has shown, most metaphors work at different levels of meaning, through processes that all contribute to amplifying the metaphoric content.

Figure 23, 24 “The hallway”

The Invention of Hugo Cabret (28–29; 30–31) Copyright © Brian Selznick 2007. Used by permission of the artist.

38

References

Bateman, John. Text and Image: A Critical Introduction to the Visual/verbal Divide. London/New York: Routledge, 2014.

Doonan, Jane. Looking at Pictures in Picturebooks. Woodchester Stroud: The Thimble Press, 1993.

Douglas, Virginie. “Dave McKean.” Images Des Livres Pour La Jeunesse. Ed. Annick Lorant-Jolly and Sophie Van der Linden. Paris: Éditions Thierry Magnier / CRDP académie de Créteil, 2006, 140–145.

Eerden, Bart. “Anger in Asterix: The Metaphorical Representation of Anger in Comics and Animated Films.”

Multimodal Metaphor. Ed. Charles Forceville and Eduardo Urios-Aparisi. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter,

2009, 243–264.

El Refaie, Elizabeth. “Understanding Visual Metaphor: The Example of Newspaper Cartoons.” Visual

Communication 2.1 (2003), 75–95.

Fahlenbrach, Kathrin. “Embodied Spaces: Film Spaces as (Leading) Audiovisual Metaphors.” Narration and

Spectatorship in Moving Images. Ed. Joseph Anderson and Barbara Fisher-Anderson. Cambridge, MA,

USA: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2007, 105–123.

Forceville, Charles. “Pictorial and Multimodal Metaphor.” Handbuch Sprache Im Multimodalen Kontext. Ed. Nina Maria Klug and Hartmut Stöckl. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2016.

___. Pictorial Metaphor in Advertising. London: Routledge, 1996.

Gaiman, Neil, and Dave McKean. The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish. 1997. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2004.

Hanks, Patrick, ed. Collins Dictionary of the English Language. London: Collins, 1979.

Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina. “Metalinguistic Awareness and the Child’s Developing Concept of Irony: The Relationship Between Picture and Text in Ironic Picturebooks.” The Lion and the Unicorn 23.2 (1999), 157–183.

Lewis, David. Reading Contemporary Picture Books: Picturing Text. New York: Routledge/Falmer, 2001. Norris, Michele. “The Intricate, Cinematic World of Hugo Cabret.” 2007, unpaged.

Painter, Clare, James Robert Martin, and Len Unsworth. Reading Visual Narratives – Image Analysis of

Children’s Picture Books. N.p., 2013.

Ricœur, Paul. La Métaphore vive. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1975.

Schwarcz, Joseph. Ways of the Illustrator: Visual Communication in Children’s Literature. Chicago: American Library Association, 1982.

___. The Invention of Hugo Cabret. New York: Scholastic Press, 2007.

Sendak, Maurice. Caldecott & Co: Notes on Books and Pictures. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1988.

Sipe, Lawrence. “Revisiting the Relationships Between Text and Pictures.” Children’s Literature in Education 43 (2012), 4–21.

Tan, Shaun. Rules of Summer. Sydney: Hachette Australia, 2013.

___. “Words and Pictures, an Intimate Distance”, 2010. www.shauntan.net/images/essayLinguaFranca.pdf. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

Gras, Isabelle (Université Bordeaux Montaigne, France): isabelle_gras@yahoo.com

Après un Master de recherche en littérature française incluant un contrat d’enseignante auxiliaire de français à San José State University en Californie en 2004, suivi d’un Master de Recherche en didactique de l’anglais à l’Université Montesquieu Bordeaux IV en 2013, Isabelle Gras, enseignante de l’Éducation Nationale, est actuellement étudiante en doctorat d’études anglophones à l’Université Bordeaux Montaigne, sous la direc-tion de Nicole Ollier.