Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

HB31

.M415

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working

Paper

Series

Civil

Rights,

the

War

on

Poverty,

and

Blaci<-White

Convergence

in

Infant

Mortality

in

the

Rural

South

and

Mississippi

Douglas

Almond

Kenneth

Y.

Chay

Michael

Greenstone

Working

Paper

07-04

December

31,

2006

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research

Network Paper

Collection

athttp://ssrn.conn/abstract=961 021

MASSACHUSETTS

;Ni^ .OFTECriNOa)C

'-FEB

t 52007

jLIBRARIES

Civil

Rights,

the

War

on

Poverty,

and

Black-White

Convergence

inInfant

Mortality

inthe

Rural South

and

Mississippi*

Douglas

Almond,

Kenneth

Y.

Chay, and Michael

Greenstone

December

2006

*

We

thankGary

Becker,David

Card, JohnDiNardo, Michael

Grossman,

Jon Gruber, LarsHanen,

James

Heckman,

Ted

Joyce, Allen Lapey, Ellen Meara,Kevin

Murphy,

Derek

Neal,Doug

Staiger, JillQuadagno, and

seminar participants at Berkeley, Chicago, Harvard,MIT,

and

theNBER

Summer

InstituteChildStudies

Workshop

forhelpfulcomments.

We

areespecially indebtedtoDick Johnson and

Harold

Armstrong

of the Mississippi StateDepartment

of Health, JoanExhne

of the University of Southern Mississippi, SarahHaldeman

of theLyndon

B.Johnson

Library,and

Gary

Kennedy

oftheBureau

ofEconomic

Analysis for their invaluable assistance withsome

ofthe data used in this study.Chuan

Goh,

ElizabethGreenwood,

Heather Royer, Stacy Sneeringer,and

PaulTorelliprovided excellentCivil Rights, the

War

on

Poverty,and

Black-White

Convergence

inInfantMortalityinthe

Rural South

and

MississippiAbstract

For

the last sixty years, African-Americanshave

been

75%

more

likely todie during infancy as whites.From

themid-1960s

to the early 1970s, however, thisracialgap narrowed

substantially.We

argue thatthe ehmination of widespreadracialsegregation in Southern hospitals duringthisperiodplayed a causal

role in this

improvement.

Our

analysis indicates that TitleVI

of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,which

mandated

desegregation in institutions receiving federal funds, enabled 5,000 to 7,000 additional blackinfants to survive infancy

from 1965-1975 and

atleast25,000 infantsfrom

1965-2002.We

estimatethatby

themselves theseinfantmortahtybenefitsgenerateda welfare gain ofmore

than$7 billion(2005$) for1965-1975 and

more

than$27

billion for 1965-2002.These

findings indicate that the benefits ofthe1960s Civil Rights legislation extended

beyond

the labormarker and were

substantially larger thanrecognizedpreviously.

Douglas

Almond

Department

ofEconomics and

SIPA

Columbia

UniversityInternationalAffairsBuilding,

MC

3308

420

West

118thStreetNew

York,NY

10027

and

NBER

da2

152@columbia.edu

Michael

GreenstoneMIT

Department

ofEconomics

50Memorial

Drive,E52-391B

Cambridge,

MA

02142

and

NBER

mgreenst@mit. edu

Kenneth

Y.Chay

Department

ofEconomics

UniversityofCalifornia,Berkeley

549

Evans

HallBerkeley,

CA

94720

and

NBER

I.Introduction

In 1965,

40

AfricanAmerican

infants diedforevery 1,000bom

inthe U.S.-

aratecomparable

tocurrentlevels inIndia orIran.

Over

thenextten years, theinfant mortalityrateamong

U.S. blacks fellto24

perthousand.Among

black infantsbom

in1975, roughly 7,000more

babiessurvivedtoage 1 thanifthe pre-1

965

trendhad

continued. Further, the gapbetween

blackand

white infantmortalityrates(IMR)

narrowed

substantially duringthelate 1960sand

early 1970s (Figure la). Indeed, these years comprisethe soleperiodoflargereductionsintheblack-whiteinfantmortalitygapsince

World

War

II.'In this paper

we

establish thatmuch

of the 1965-75improvement

in black infant healthwas

driven

by

a sharp decline in post-neonatal mortality rates(PNMR)

in the rural South.^ Figure lb, forexample,

shows

thenumber

ofpost-neonatal deathsamong

blackand

white infants due to diarrhea andpneumonia

inthe stateofMississippi. In the early 1960s, post-neonatal death ratesfor thesetwo

causeswere

6-7 times higheramong

blacks than whitesand

showed

no

trend toward relative improvement.Starting in 1966, however, the

number

ofdeathsdue

to these causesplummeted

among

black infants,while the

number

for whitesremained

nearly constant. This dramatic trend breakin fatalities forthesetwo

causes is important because they contributed to a high fraction ofoverall black infant mortahtyand

effectivetreatmentsforbothconditions

were

wellknown

and

widelyused.We

arguethatthetrendbreakinblackIMRs

in themral

Southwas

drivenby

federallymandated

desegregationefforts thatincreasedaccess tohospital care forblackinfants.

Of

theevents thatledtothemandated

desegregation,two

stand out as central.The

passage ofTitleVI

ofthe CivilRightsAct

inJuly1964

prohibited discriminationand

segregation in any institution receiving federal funds. Second,hospital eligibilityfor

payments

underthenew

Medicare

program

-

begun

July 1,1966

-

was

conditionedon

eliminationofthe racially discriminatory practicesthatwere

common

atthe time. Together,the CivilRights

Act and

the financial leverage exercisedby

theJohnson

administration led to the opening ofpreviously "white-only"hospitalstoblacks

and

theend ofexplicit racial segregationinhealthcare.'

The

National CenterforHealth Statisticsswitchedfromcoding racebased onthe infant's race to therace ofthe

motherin 1990. Consequently, itisimpossibletoextendtheseseriesbeyond 1990inaconsistentmanner.

"Conventionally, infant mortalityis definedas the deathrateofinfantswithintheirfirstyear oflife. Post-neonatal

mortalityisthedeathrate intheperiodfrom 28daysto 1 yearafter birth. Neonataldeaths are thosethatoccurinthe first28daysafter birth.

We

implement

a battery oftests to evaluate thehypothesis thathospital desegregationcausedthelarge reductions intheblack-white

IMR

gap.The

results ofthese tests are strongly supportive. First,thereduction in the black-white

IMR

gapbegan

immediately after integrationand

was

largest in the ruralSouth

where

blacks' access to hospitalswas

themost

constrained. Second, within the rural South, thedecline

was

concentratedamong

post-neonatal deaths,which were

more

preventable than neonatalfatalities at the time.

Roughly

two-thirds ofthe decline in relativePNMRs

was due

to a reduction inpneumonia

andgastroenteritisdeaths,two

causespreventableby

hospitaltreatment.The

most

demanding

testcomes from

a case study of Mississippi. Despite strong financialincentivesprovided

by

Medicare,many

hospitalsin Mississippiwere slow

to integrate.We

evaluate theimpact ofthose delaysusingan event-study approachthat is based

on

detailed,hospital-leveldataon

thetiming ofhospital compliance with Title VI.

We

findimmediate

and

large reductions in post-neonatalmortality, especially

among

conditionsmost

treatable in hospitals,when

a hospital in the county ofresidence

was

certified as desegregated.These

gainswere

not sharedby

white infants,and

they arerobusttoadjustmentforvarious alternativehealth determinants,such asmaternalcharacteristics(e.g.,age

and

marital status), transferpayments

(includingFood

Stamps),Medicaid

participation,and

per-capitaincome. Further, the

same

approach findsanimmediate

and

sharp increase inthe fraction of blackbirthsinhospitals,

which

corroborates thevalidity ofthe federal governments' claims ofsuccessful integration.Thus,the evidence appears inconsistent withalternative explanations, including an innovationinmedical technologyor a

change

blackinfants'home

environments.Overall, our analysis indicates that this federally

mandated

desegregation of hospitals enabledover 5,000 black infants to survive until age 1

between

1965and

1975 in the rural Southand

25,000 through 2002.We

estimate thatthe infant mortality benefits alonewere

equivalent to a welfare gainof$7.2 to $11.1 billion (2005$) for blacks

bom

in the rural Southfrom

1965-1975.For

the1965-2002

period,

we

estimate gainsbetween

$27.5and

$41.9 billion.These

findings indicate that the benefits ofthe 1960s Civil Rights legislation extended

beyond

the labormarket outcomes

considered previously(Chay

1995;Chay

1998;Donohue

andHeckman

1991;Heckman

and Payner

1989). Consequently,we

The

paper proceeds as follows. Section II provides a brief history ofthe federallymandated

desegregation of hospitals. Section III uses state

by

urban/rural data to test the hypothesis that themandated

desegregation accounts fora substantial fractionoftheimprovement

intheblack-whiteIMR

inthe decade after 1965. Section

IV

reportson

the Mississippi event studyand

its results. SectionV

interpretstheresults,

and

SectionVI

concludes.II.

The

FederallyMandated

Desegregation

ofHospitalsA. Segregation

and

Scarcity:Blacks'AccesstoHospitalsPriorto1965

Hospitals

and

other health facilities,which

shouldbethe institutionsofhealing,oftenbecause ofdiscrimination

become

themeans

ofshorteninglife.(RobertNash,DirectorofOfficeof Equal Health Opportunity, 1966)

The

Southwas

a deeply segregated society throughout the 1950s and early 1960s. Thisseparation ofracesextended to all areas oflife, including the provision ofhealth services.

A

Journalof

theNational

Medical

Association survey of 523 hospitals administeredin1955-1956

foundthatwhile 87 percent ofhospitals intheNorth

had

a "policy ofintegration", only 1 percent ofhospitals in the Southhad

one. Further,a 1956 survey of2400

Southernhospitaladministrators foundthatonly 17 percentwere

wiUing

to accept desegregation, with 62 percent adamantly opposed, 10 percent favoring separatehospitals,

and

11 percent unwilling to respond(Seham

1964).These

policies continued into the early1960s.

A

1963 survey found that 85 percent of southern hospitals reported"some

type of racialsegregation or exclusion,"

compared

to less than 2 percent in northernand

western states (U.S.Commission

on

Civil Rights 1963:141).The

pattern ofdiscrimination usually "consisted ofa separatewing

or floor forNegro

patients"insingle-building hospitals (U.S.Commission

on

CivilRights 1966:10).A

relatively unrecognized^ aspect of hospital segregationand

exclusion in the Southwas

thefederal government's role in supporting itboth legally and financially through the Hospital Survey

and

Construction

Act

of1946, alsoknown

as theHill-BurtonAct.Two

decades afteritsenactment, 350,000hospitalbeds (orapproximately halfofthe existing beds inthe

US)

had

been

constructed undertheHill-Burton

program.''As

Hill-Burton fundingwas more

generousinpoorerareas(DHEW

1966), the federalgovernment

was

thedominant

force in the postwar hospital construction in the South.The

1946^Reynolds

(1997) and Smith(1999,2005) are notable exceptions.

"

Almond

legislation that enactedHill-Burtonexplicitlyinvokedthe principleof"separatebut equal" with regardto race. Thisclause

remained

despite thefact that otherparts ofthe legislationwere

amended

and

extendedseveral times both before

and

after the 1954Brown

vs.Board

of Education

decision that "separate butequal"

was

unconstitutional.^'^Moreover,

the Hill-Burtonprogram

funded health care facilities thatspecifically excluded individuals

on

the basis of race.'The

Hill-BurtonAct

was

the only federallegislation to codify racial segregation

and

exclusion since the 19th century (Smith 1999).As

Seham

noted in the

New

England

Journalof Medicine

in 1964,"To

20,000,000 citizens, discriminationand

segregationfollowed"

from

theseparate -but-equal clauseoftheHill-BurtonAct.Table 1 presents evidence that black hospital patients in the rural South

were

tremendouslyunderservedrelative towhites throughthe early 1960s. Panel

A

ofTable 1 reports the fraction of blackinfants

bom

in hospitals with doctors present for1955-1965 by

region.*''While

black hospitalizationrates forlabor

and

delivery approachedthose of whites inthe urban areas oftheNorthand "Elsewhere"

(largelythe

Midwest

and

West),largegapsexisted intheSouth.For

residentsoftheRuralSouth,40%

ofblack babies

bom

were

not bora in a hospital with a doctor present, while thecomparable

figure forwhites

was

only4%.

The

racial disparitywas

still larger in Mississippi;more

than halfof black infants'

After the

Brown

decision, Hill-Burton program administrators repeatedly requested that the program ceasefollowingthe"separate but equal"doctrine. For example, aFebruary 1963

memo

fromtheGeneral Counsel attheDepartmentofHealth, Education, and Welfareto theAssistant Surgeon General states, "Theacceptanceofinternal

segregation atinstitutionswhichadmit bothraces isalso,Ibelieve,inaccordwiththeintent of Congressatthetime

when

thelegislationwas enacted,and in this respect alsoCongresshasmade

nochangetothelaw"(DHEW

memo

February 12, 1963:1). This

memo

goesonto arguethatHill-Burton"administrative officers"have nochoicebuttocontinue to award grants to segregated health care facilities "despite any doubts they individually

may

entertainregardingthe constitutionalvalidityofthestatutes" (ibid).

^

As

lateas August, 1963, theU.S Senaterejected aproposalthatwould haverequired grantsunderthe Hill-BurtonActtohospitalsthatdidnot discriminateonthebasisofrace (U.S.Court ofAppeals FourthCircuit1963:23)

'a hospital constructed withHill-Burton

money

could exclude a race outright ifithad indicatedin its applicadonthat "certain persons in this areawill be denied admission to the proposed facilides as padents because ofrace,

creed, orcolor" and reportedto theSurgeon General thatotherfacilities fortheexcluded racewereavailable (U.S.

Court ofAppeals Fourth Circuit 1963:7).

A

total of89 hospital construction projects in 14 stateswere approvedwiththestipulation thatonlyoneracewouldbe admittedtothefacility(U.S.Commission onCivilRights

1963:130-131). Ninetypercentofthefundsforthese discriminatingfacilitieswentto all-whitefacilities.

*Thisistheonlymeasureofhospitalaccess availablefromthevitalstatisticsdata.

'

We

define the "Rust Belt" states as Illinois, Michigan,New

York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. The South iscomprised of 17 states (including Washington DC), as assigned by the

US

Census Bureau.We

refer tonon-metropolitan and metropolitan counties as the "rural" and "urban" areas ofa state. With the exception of

New

England, counties are classified as "metropolitan" if they are included in a Census Bureau-defined Standard

Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA). Race was coded aswhite and non-white inthe Vital Statistics data in this

period. In 1968, the non-white categorywas subdivided and

we

found thatblacksaccountedfor99%

ofnonwhiteinfant deaths intheUrban Rustbelt,Urban South,Rural South, and Mississippi. Thecomparable figure forUrban

Elsewhere is 93%.

We

exclude Rural Elsewhere from the analysis because blacks only accounted for 52%i ofwere

bom

outsidehospitals,versus2%

ofwhites.Panel

B

uses dataon

thenumber

of hospital beds available for whiteand

"colored" patientscollected

by

the MississippiCommission

on

Hospital Care.'°The number

of hospital beds per 1,000births allocated to blacks versus whites in the early 1960s is reported." This

measure

of access tohospital careis relevantbecause certainlife-savingtreatments for infants

were

onlyavailable athospitals.More

than twice asmany

hospital bedswere

available to whites as blacks in the predominantly whitecounties.

More

than five times asmany

hospital bedswere

available to whites as blacks in thepredominantly blackcountiesofMississippi.'^

Low

hospitalization ratesand

bed

ratios reflected the inferiormedical

care available toblacks

tmder

segregation.Senator

Javitsof

New

York

stated to the U.S. Senate:"Segregated

hospitalsand

segregated

wards have

resulted inover-crowded

conditionsand

substandard

facilities for

many

Negro

patients,"who

are often "relegated tobasement and

atticwards."

Javits further

noted

that:"Often

when

Negro

wards

are filled,no

additionalNegro

patients areadmitted

even

though

theremay

be

empty

beds elsewhere

inthehospital." (Javits 1962).B.

The

End

of Legalized SegregationinHealthCare

FacilitiesJim

Crow

was

a persistent feature of southern hospitals well into the 1960s.'''Below,

we

highlight three

landmark

events ofthemid-1960s

thatwere

instrumental in ending racial segregation inthe

American

healthcare system.These

events involvedallthreebranches ofgovernment

in turn: judicial,legislative, andexecutive.

'"

That such data were collected annually reflects the degree to whichracial segregation was institutionalized in

Mississippi. Through 1964, MississippiStatelawrequiredthat inhospitals"maintainedbythe Statefortreatmentof

white and coloredpatients,"hospital administrators mustprovideseparate entrances forwhitesandblacksandthat

the entrances"shall be usedbythe races onlyfor whichthey areprepared." Further, theGovernorofMississippi

was

empowered

to remove any administrator failing to comply with this law (Dept. of Health Education andWelfare

memo,

June 26, 1964:6). Mississippiwastheonlystateinthe nationthatrequired segregationinstate-runhospitals

(DHEW

memo,

January31, 1956). ''

We

have bedsdatabyrace for 1960, 1962, 1963 and 1964 andcomputetheratio to birthsoccurringinthese years.'"

The

findingofgreaterdisparities inaccess inthepredominantly blackcounties issimilartoBond's (1939) studythatdemonstratesthatblack schoolswere ofa higherqualityincountieswhere blacksformeda smaller fractionof

thepopulation.

We

thankananonymous

refereeforpointingthisout.'^ There was even evidence that Southerners' commitment to this system was growing as a reaction to the

burgeoning Civil Rights movement. Caro (2002) argues thatthe early stages ofthe Civil Rights

movement

in the1950s led to increased violence by whites against blacks and a renewed focus on preserving the system of

First, in 1963, Dr.

George

Simkins, a black dentist in Greensboro,North

Carolina, joined with black patients and other physicians in suingtwo

hospitalswhich

denied blacks admissionand

staffprivileges.

These

hospitals, although private,had

received federal Hill-Burton construction funds. InNovember

1963, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals decided Simkins v.Moses

H.Cone Memorial

Hospital in favor ofthe plaintiffs.

The

court declared that the section of the Hill-Burton legislationpermitting "separate-but-equal" health facilities

was

unconstitutional.''' Furthermore, the majorityopinionstated: "Racial discriminationin medicalfacilities is atleastpartlyresponsible forthe fact that in

North

Carolinathe rate ofNegro

infantmortality is twicetherate forwhites...." (U.S. Courtof Appeals

FourthCircuit 1963:14)'^In

March

1964, theSupreme

Court declinedto review theAppeals

Court decision, leaving it inplace.

The

immediate

resultofthisdecisionwas

thatnew

applications forHill-Burton fundsand

pendingprojects

were

allrequiredto be nondiscriminatory withrespectto admissions, staffprivileges,and

accessto all portions ofthe facilities (Smith 1999). Since halfofall Hill-Burton grantees

were

private,non-profits

(DHEW

February 12, 1963),thisruling's impactwas

notsimplylimitedtopublic healthfacilities.However,

this ruling did not affect segregated hospitals thathad

previously received Hill-Burtonfunding.'^ In fact,

lawmakers

cited the Simkins case as demonstrating theneed

for definitive federallegislation.

Passage ofTitle

VI

ofthe Civil RightsAct

in July 1964,which

prohibited discriminationand

segregationinanyinstitutionreceiving federal funds,

was

the secondlandmark

event.'''According

to thebipartisanU.S.

Commission

on

Civil Rights,"Seldom

has anypieceoflegislationbeen

sobroadinscope,sweeping

across departmental, geographicaland

political lines, as TitleVI

ofthe Civil Rights Act of1964"

(U.S.Commission

on

Civil Rights 1966;1).The

passage of the legislationby

itself led to asubstantial integration ofhospitals inthe South duringthe remainderof 1964 and 1965.

However,

there'*

Reynolds, 1997refers toSimkinsas "the

Brown

caseforhospitals."' This viewwas alsoexpressedbythe medical community. Forexample, see

Seham

(1964) intheNew

EnglandJournalofMedicine andNash(1968)intheAmericanJournalofPublicHealth.

'^Accordingto the 1963 survey by the

U.S. Commission onCivil Rights,

60%

of segregated healthfacilities hadreceivedHill-Burton funds: Reynolds(1997).

'^

In particular, Title VI stipulated that"Patients must be admittedto facilities without regardto their race, creed,

color, ornational origin.

Once

admitted, patientsmusthave access to allportions ofthefacility andto allserviceswithout discrimination. They

may

notbe segregated withinanyportionofthefacility,provided a different service,restricted in their enjoyment ofanyprivilege, or treated differentlybecause oftheirrace,creed, color, ornational

remained

pocketsofnoncompliance

insome

hospitals andinsome

practices (e.g.,integrationof

patientswithinwards),

even

within hospitalsthatclaimedtocomply

withTitleVI

(ibid).The

final eventwas

the inception oftheMedicare

program

in July 1966. Following directionsfrom

President Johnson, eligibility forMedicare

reimbursement required that hospitalsend

racialdiscrimination.'^

One

observerhas noted: "...Medicarepayments

to hospitalspromised

to be generous,and

thereby essential. In essence, hospitalshad

to choosebetween

affluence throughcompliance and

bankruptcy" (Smith, 2005:320).'' Further, in themonths

leadingup

to July, a "Children'sCrusade"

of750

federalemployees

under the Office of Equal Health Opportunityworked

to ensure hospitalcompliance

withTitleVI

throughon-siteinspections(Smith 1999:1 13)."°By

June30, 1966, 92percentofallhospitalbedswere

in compliance withTitleVI

(Ibid: 141). InJuly

and

throughthefallof1966, the Officeof Equal Health Opportunityworked

tosecurecomplianceinthe remaining hospitals.^' This "quiet revolution"

meant

that insouthern hospitals:"Negroes

are being admittedand

treated asanyone

else for the first time"(Nash

1968:246) Notably, Mississippi hospitalswere

among

themost

intransigenttothesechanges,which

we

exploitinthebelow

analysis.C. Gastroenteritis,

Pneumonia,

and

theBlack-WhiteMortalityGap

Prior to the

development and

diffusion of technologies benefiting prematureand

low-weightinfants duringthe 1970s

and

1980s,^^ medical carewas

most

successflil inpreventing deaths during thepost-neonatal period (1-12

months

after birth). Post-neonatal deaths tended to be caused by negative'*

In a speech to the American public the night before Medicare went into effect, Johnson said, "Medicare will

succeed-ifhospitals accepttheirresponsibilityunderthelawnottodiscriminate againstanypatientbecause ofrace"

(quotedinReynolds 1997). Alsosee

Quadagno

(1999)."

The

formerdirectorofthe Mississippi State Hospital Association,Thomas

Logue,referredtotheearlyMedicare programasa"goldmine"forMississippihospitals.^^

Robert

Nash

(Director of Office of Equal Health Opportunity,PHS)

wrote about the process of enforcingintegration ofhealth carefacilities,

"Some

people havecomparedouradministration ofTitle VIto the practicesofsome

oftheworld'soutstandingdictatorships"(Nash 1968; 251).^'

Reynolds (1997) quotes WilburCohen,

who

as the Secretary ofHEW

was aprincipal architectofthe Medicarelegislation:"There isone otherimportantcontributionofMedicareandMedicaidwhichhas not yet received public

notice-thevirtualdismantlingofsegregationofhospitals,physiciansoffices,nursinghomes, andclinicsasofJuly 1,

1966....If Medicare and Medicaid had not

made

another single contribution, this result would be sufficient toenshrineitasone ofthemostsignificantsocialreformsofthedecade[ifnot the century]."

^^

Two

key changesin the treatment of neonates during thepast40 years were the advent ofrespiratory therapy

techniquesand improvements in mechanical ventilation in the 1970s and the introduction ofsurfactant therapy in

1989. Further, most ofthe diffusion oflocal specialized neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) occurred in the 1980s.

events after birth, usually infectious diseases

and

accidents(Grossman and

Jacobowitz 1981). Forpneumonia

and

gastroenteritis infections in particular, death could be prevented with timely medicaltreatment,^^ in part a resuh ofgreater availabiUty ofantibiotics following

World

War

II (Shapiro et al,1968). Antibiotics

were

administeredintravenously, togetherwithfluids,inhospitals.Prior to

World

War

II,pneumonia and

gastroenteritis accounted for halfofpost-neonatal deathsfor blacks

and

whites alike.^''By

1965, thesetwo

causes accounted for under a third of whitepost-neonatal deathswhilestill comprising

45%

of black post-neonatal deaths.The

postwar surge in hospitalcapacity financed

by

the Hill-BurtonProgram

succeeded in reducing infant mortality, but these benefitswere

concentratedamong

whites(Almond

etal.2006b).By

1965, blackswere

fourtimesas likely to diefrom

gastroenteritisand pneumonia

in the post-neonatal period as whites. Thus, the primary factorunderlyingthe

widening

black-whiteinfantmortalitygap

after 1947

(seeFigure 1a)was

thedivergenceinblack

and

white experiences withthesetwo

eminentlytreatable afflictions.D.Implications

Thispaper's goal is to assess

whether

the federallymandated

integration ofhealth care facilitiescaused at leastpart ofthe

improvement

in black infant mortality ratesdocumented

inFigure 1a. In theabsence ofa

randomized

experiment,we

proceedby

presenting aseries ofincreasinglydemanding

tests.Specifically ifthere is a causal relationship, then the

above

historical context suggests that the datawillfailto rejectthe following hypotheses aboutthedeclineintheblack

IMR

after1965:1

.

Itshouldexceed the declineinthewhite

IMR.

2. It should disproportionately occur in the areas of the country

where

segregation and inadequate supplywere

more

pervasive.3 .

Itshould disproportionately occur

among

causes of death that aremore

responsive to accesstohospitals.

4.

Among

the causes of death that are preventable with hospital access, it should respondquicklytointegration.

The

remainder ofthepaperimplements

tests ofthesefourhypothesesand

failsto rejectthem.III.

Regional

Evidence on

theConsequences

oftheMandated

Desegregation

of Hospitals"^ With

regard to gastroenteritis,

Emery

(1976:204) writes that the mortality rate relates to "the eariiness [or]latenessofdiagnosis and admissionto hospital." Similarly forpneumonia, a 1964pediatrics textbookstates: "The outcomeisdependentuponearlydiagnosisandtheappropriatenessof[medical]treatment"(Nelson 1964:847-848).

"

Shapiroetal. (1968):Appendixtables1.2dandI.2e.There is

no

question that if thesame

carewere

available toNegroes

inMississippi

and

otherSouthernstatesasinMinnesota

andotherNorthernstates,Negro

morbidityand

mortalityratescouldbe sharplyreduced.(Max

Seham,New

EnglandJournalofMedicine: 1964)A.

Data

Surprisingly

few

studies exist of long-run trends in therelative health of black infants overtime.In addition, the existing research is based

on

highly aggregated data, both across regionsand

overtime,which

provide little informationon

theprecise locationand

timing ofinfant mortality changesby

race.Consequently, evidence on the specificfactorsunderlyingsignificantchangesinblack-whiteinfant health

outcomes

issparseand

often anecdotal.To

document

the locationand

timing of improvements,we

entered datafrom

the1955-1975

publicationsoftheVitalStatisticsoftheUnited States.

Drawn

from

standardcertificates oflive birthand

death, theycoverthe universeofbirths

and

deathsintheUnited States in eachyear.We

entered annual,race-specific (white

and

non-white) seriesfor ruraland urban areas of eachstate.Our

focus ison

infantmortality rates, the ratio ofinfant deaths within a year ofbirth to thetotal

number

oflive births in thatyear (expressed as deaths per 1,000 live births),

and

we

also distinguishbetween

deaths in the neonataland

post-neonatal periods.As

discussed in the previous section,we

focuson

the Rural South,Urban

South,

Urban

Rustbelt,Urban

Elsewhere,and

Mississippi.'^We

also obtained individual-level electronic mortality data for the years 1960-1975."^Unfortunately, analogousnatality micro-dataare available only beginningin 1968. Nevertheless,

we

canuse the 1960-75 mortalitymicrodatatogetherwith natalitydataaggregated

by

urbanand

ruralregions ofeach state. This enables us to analyze trends in mortality rates

due

topneumonia and

gastroenteritis.These

causes accountedfor39%

ofallpostneonatalfatalitiesinthe 1960-65period.B. Trends inBlack-WhiteInfantMortalityRatesby Region,

1955-1975

Figure 2 plots the difference in black and white infant mortahty rates

by

region for the years1955-1975. Clearly, large gaps ininfant mortality rates existed throughoutthecountry. In thefirsthalf

^^Almost 80 percent of

allnonwhite birthsfrom 1955-75 werein eitherthe Southor theurbancountiesoftheRust

Beltstates. The UrbanElsewherecounties accountedforanother 16 percent. Duringtheperiod, 28and26percent

ofallbirths intheruraland urbanSouth, respectively,werenonwhite;comparedto 17percentintheurbanRustBelt

and 11 percentinallotherurbancounties.

of

the period, the differencebetween

blackand

whiteinfantmortahty ratesdisplaysno

obviouspattern-remaining roughly constant in

some

regionsand

actually expandingin others.Between

1965and

1975,however, the racial gap

narrowed

in all regions.The

timing ofthis convergence is consistent with our hypothesis that federallymandated

integration ofhealth care facilitiesbegun

in themid-1960s

caused animprovement

inblackinfant mortalityrates.Examination

of the regional pattems in mortality gaps provides amore

demanding

test.Specifically,

we

expect that the decline should be greater in regionswhere

segregationand

restrictedaccess

were

pervasive. Again,these mortalityseries supportthisprediction. Forexample

among

thefourregions, the largest decline

from

1965-1975 occurred in the Rural South,where

the pre-existingdisparities in access

were

the greatest (recall Table 1). In this region, the racial gap declinedby

11.4deathsper 1,000births, closing fullyhalfoftheinitial disparity.

To

putthisnumber

in context, itmeans

that4,700

more

blackinfantsbom

in 1975 survived toage 1 than ifthe 1965 black-white differencestillheldin 1975.^^ InMississippi,

where

pre-1965 access differenceswere

especially glaring,the declinewas

16.4deaths per 1,000births."*

Finally, trends in the racial

gap

outside the South track each other well throughout the entireperiod.

These

regions also experienced anarrowing oftheracialgap

inthe 1965-75 period,albeit35%-40%

smaller than the decline in the Rural South.The

nexttwo

subsections furtherprobethe validity ofour hypothesis

by

estimating trend breakmodels

by

regionand

decomposing

the mortalityimprovement

intocategories

beheved

more

and

lessresponsive tohospital access.C. Trends inBlack- WhiteInfant MortalityRates by

Age and

Region,1955-1975

Ifthe equalization ofhospital access

between

blacksand

whites indeed caused the black-whiteinfantmortality gaptofall,

we

would

expectthisreductiontobe concentratedinthe post-neonatal period.To

evaluatethispossibility,we

fitsimpletrendbreakregressionmodels

ofthefollowing form:(1) ysn

=

af+P(/-1965)*

l(?>1965)

+

53r+

8srt,where

s,r,and

tindex state, urban/rural,and

year, respectively.The

dependentvariableis theneonatal or'

Calculatedas: #ofBlackBirths"" *(Black

IMR""-(White

IMR""-White

IMR'"')),for rural Southbirths. 'In theruralSouthandMississippi, theblack-whitegapwasincreasingfrom 1955-1965.

postneonatal mortalityrate.

The

equationis estimated separatelyforblacks, whites,and

theblack- whitedifference.

The

explanatoryvariables are atimetrend, t,and anindicatorvariableequaltooneiftheyearis after 1965 interacted witha post-1965 timetrendequal to {t

-

1965).a

measuresthe average 1955-65trend in the infant mortality rate across states. [3 is the parameter ofinterest

and

measures the averageslope

change

in theIMR

trend that occurred after 1965. All specifications include rural/urbanby

statefixed effects, 5sr,

which

account forpermanent

differences across rural/urban areas of states.The

numbers

of births in each race-rural/urban-state-year cell are used as weights in the race-specificregressions,

and

the weight is thenumber

of black births in the black-white regressions.The

standarderrors arecorrectedforheteroskedasticityandresidualtime-series correlationatthe state-level.

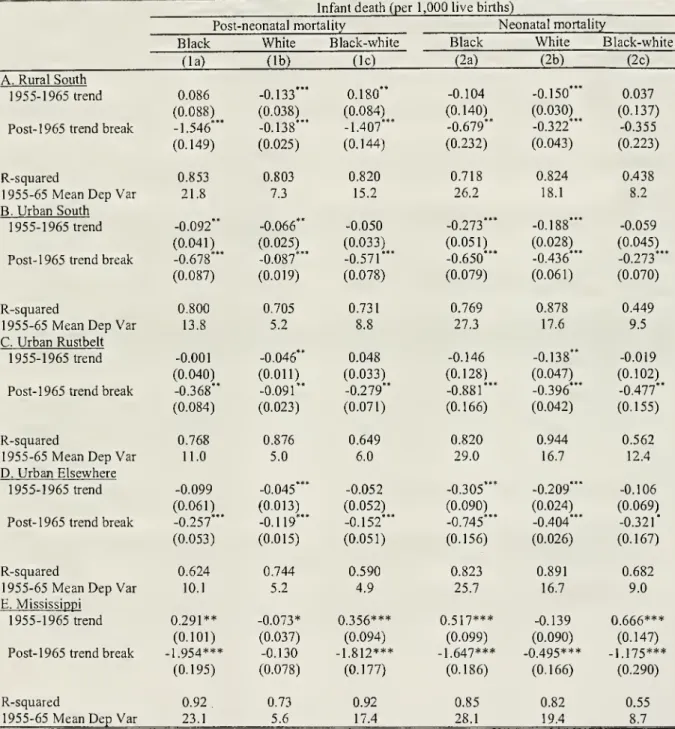

Table 2 presents the trend breakregression results forpost-neonataland neonatal mortalityrates

inthe

two

setsof columns. Within eachsetof columns, resultsforblackand

whitemortalityratesand

theblack-whitedifference are

shown,

althoughwe

focusour descriptionhere onthe difference regressionsincolumns

(Ic)and

(2c) dueto space constraints.The

panels ofthe tablecorrespond tothe fourregions inFigure2andMississippi.

The

rural Southstands outfor several reasons. First, the pre-1965

black post-neonatal mortalityrate

exceeded

the white rateby

15.2 deaths per 1,000 live births. This racial differenceexceeded

theaverage blackpost-neonatal mortality rate in each regionoutside the South. Second,the estimates

show

thatthe

gap between

black and whitepost-neonatal mortality rateswas

increasingfrom

1955 to 1965 atthe rate of0.18 deaths (per 1,000 live births) per year. Thus, conditions for blacks

were

apparentlydeterioratingrelative towhites.

Third, there

was

a largetrendbreakof about 1.4deathsper yearafter 1965. Thisimpliesthattheblack-whitemortality

gap

intherural South decreased 14deathsper 1,000 birthsmore

through 1975 thanifthe pre-1965 trend

had

prevailed. Thisimprovement

iscomparable

to the pre-existing racial gap.Moreover,

itimplies that 5,900 additional infants survivedtoyear 1 through 1975 thanwould

havebeen

expected

from

pre-1965 trends.The

racialgapinpost-neonatal mortalityratesalsonarrowed

intheother three regions.However,

theblack-white trendbreak in therural South is 2.5 times largerthan in the

Urban

South, 5 times largerthan in the

Urban

Rustbelt,and

9 times larger than in theUrban

Elsewhere.Among

these regions, themagnitude

ofthe trend break corresponds to the deficiencies in hospital access inTable 1: largest in theurban South followed

by

the urbanrustbeltand

urban elsewhere. Finally,we

notethat the largestblack-whitetrendbreakafter 1965

was

forMississippi,where

accessgapswere

greatest.After 1965,both whites

and

blacks enjoyedimprovements

inneonatal mortality, althoughblacks'gains

were

larger. Interestingly, the closing of the racial gapwas

roughly equivalent across the fourregions. Further, for blacks in

Urban

areas outside the South, the post-1965 reductions in neonatalmortalityexceededthe post-neonatal ones.^^ Forpresent purposes,

we

note thatthelargest reductions inboth mortality

and

black-white gapswere

achieved during the post-neonatal period,and

that themagnitude

ofpost-neonatalimprovements

corresponds toavailablemeasures

ofhospitalaccess.'"D. TrendsinBlack-WhiteInfant MortalityRates by

Cause ofDeath

and

Region,1960-1975

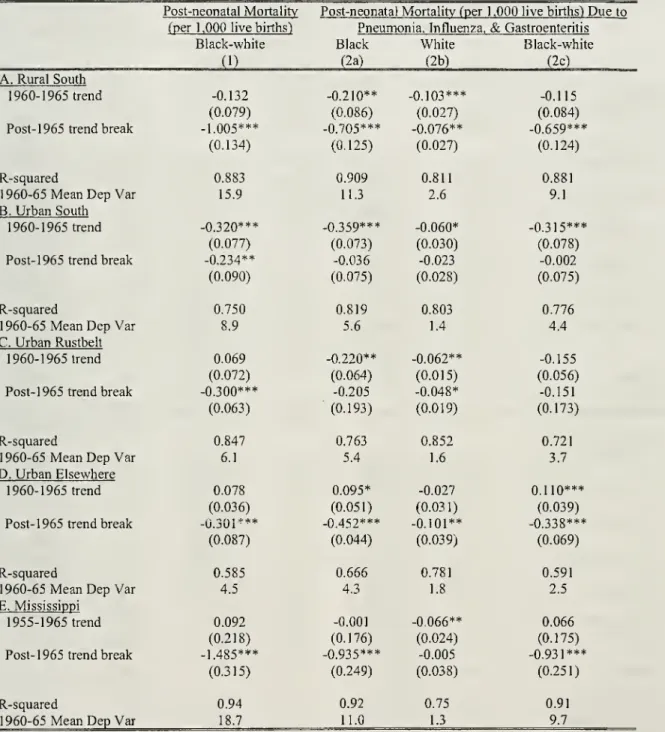

Table 3 present analogous trendbreak results for the subset ofpost-neonatal deaths caused

by

pneumonia

and gastroenteritis.As

noted,we

isolate these deaths because theywere

readilyand

necessarily treated in hospitals at the time.

Because

the data reporting cause of death are availablebeginningin I960,''

column

(1) reports trend-break estimates for allpost-neonatal deathswhen

thepre-periodis restricted to 1960-1965. This permits assessment oftheextentto

which

treatablecausesaccountforthepost-neonatal trendbreaksinTable2.

Estimates in

columns

(2a)-

(2c) indicate that largereductions inpreventable deaths occurred inthe South that

dwarfed

improvements

for whites. Moreover, the decline in deaths due to these causes accounted for roughly two-thirds ofthe entire relative decline in the post-neonatal mortahty gap.The

pattern forMississippiis similar. Thus, althoughgastroenteritis

and

pneumonia

accountedforunderhalf^'

A

comprehensiveaccounting ofneonatal mortality trends (especially inMississippi) is beyondthe scopeofthis

paper,howevertheyarelikely tobeatleastpartiallyduetotheinitiationoftheFood Stamps program

(Almond

etal.2006a) and theextension ofthe Maternal and Infant Care

Component

ofthe Maternal and Child Health ServicesProgram (Chay andGreenstone 2000; Gold,etal. 1969;Sokoletal. 1980;PeoplesandSiegel 1983;Chabot1971).

'°

Chay

and Greenstone (2000)show

that this measureofaccesswas increasingintheyears priorto 1965 for ruralsouthernblacks, but this trend acceleratedafter 1965. In regression specifications analogous to those underlying

Tables 2 and 3 for the fi-action ofbirths in hospitals, the estimated post-1965 trend break for blacks in therural

South is large and significant.

To

the extent that this measure reflects the availability ofhospital care to blackinfants after 1965, this availability improved at the time

when

post-neonatal mortality rates for Southern blacksbegan tofall. See

Chay

and Greenstone (2000)forevidenceonthe significantandpositive associationbetweenthe mortalityimprovementandtheshareofbirths in hospital."

SeeData Appendix.of post-neonatal deaths

by

the mid-1960s,^^ they accounted for nnost of the post-neonatal mortalityimprovement

for blacks. In contrast, there is little evidence ofa decline in these deaths in theUrban

South

and

Urban

Rustbelt."IV.

Event

Study Evidence

oftheImpact

of Integrationon

InfantHealth

and

HospitalAccess

A.Event Study Evidence

We

now

turn tothemost

directand

demanding

test ofthe integration hypothesis, conducted with anew

data filecompiled

for this purpose.Medicare

certification dates for the roughly 100 Mississippihospitals

were

obtainedfrom

theJournalof

theAmerican

Hospital Association annual guidesissues.We

combined

these datawithannual, race-specific county-levelvitalstatistics data forMississippi, includingthe

number

of neonataland

post-neonatal fatalitiesby

broad cause of death categories, thenumber

ofbirths ina hospital with adoctorpresent,totalbirths, the distributionofbirths

by

maternal age (under 15,15-19, 20-29, 30-34,

and

35 orolder), and the fraction of"illegitimate" births.^'' Finally,we

compiled

county-level data on federaltransferpayments, broken out by categories (e.g.

Food

Stamps) andcounty-level

income

per-capita. SeetheData

Appendix

forfurtherdetails.We

implemented

an event-study analysisofthe impacts ofthepresenceofatleastoneMedicare-certifiedhospital in acounty on infanthealth

and

hospital access usingthesedata. Specificallywe

fitthefollowingequation:

6

(2)

yc

=

ttc ?+

X

Tii 1(xc,=

i)+ Xc'P

+

ric+

U

where

c references countyand

t indexes year, x denotes the event year, and itis normalized so that foreach county x

=

1 inthe firstfull yearthatthe firsthospital within its boundaries is certified asMedicare

eligible.

Among

the 80 Mississippi counties with complete data," x=

I for 47 counties in 1967, 11 in'^For

1964-1966,gastroenteritis and pneumonia accountedfor

43%

ofallpost-neonatal deaths intherural South,and

37%

ofpost-neonatal deaths nationally.Among

blacks,thesecausesaccountedfor49%

ofpost-neonataldeathsintheruralSouth and 45%)nationally.

^^

The

entire declineinpost-neonatalfatalitiesamong

urban Elsewhereresidents,whilesubstantiallysmallerthanintheruralSouthandMississippi,isaccountedforbyfewerpreventable deaths. This findingisan interestingsubject

forfuture research.

^''

For 1959-1970,

we

obtained these vital statistics data by filing atreedom of information act request with theMississippi State Department ofHealth.

We

then extended these data through 1975 with the publicly-available NatalityandMortahty Vital Statisticsdatafiles.''

Vitalstatistics dataforBlacksinItawambaandTishomingocountieswereunavailable.

1968, 5 in 1969, and 17 in 1970.^^ Data

from

each county are restricted tothe 13 yearsrunningfrom

theseven yearsbefore acounty'sfirsthospital

was

certifiedforMedicare

throughsixyears afterward(i.e., -6<

T<

6).The

dependent variables are the post-neonatal mortality rate for all causesand

for preventable(i.e.,

pneumonia

andgastroenteritis) causesamong

countyresidents.We

also use the percentof

births inhospitals witha doctor present as a dependent variable totestfor differential changes in hospital access

by

raceasan implicit "first-stage"testofthe integration hypothesis.A

failuretofindincreasedaccessforblacks

would

undermine

the claim that greater access caused theimprovement

in infant healthdocumented

in thissubsection.Equation(2) includes atimetrendthat isallowedtovaryatthe county level(i.e., a^).

The

vectorXct includes the fraction ofmothers in the five age categories listed above, the fraction of mothers that

were

unmarried, county-level per-capita income,and

county-level per-capita transferpayments

(net ofmedical insurance payments)."

The

specification also includes fixed effects for each county (i.e., tjc).The

equation is estimated separatelyforblacks,whites,and

theblack-white differenceand

it isweighted

by

thenumber

ofblack,white,and

blackbirths,respectively, ^ctisthe stochastic errorterms. Finally, thestandarderrorsarecorrectedforheteroskedasticity

and

clusteringatthe county-level.The

parameters ofinterest are the six TCi's.They

separately test formean

shifts in county-levelpost-neonatal mortality rates(and hospital access), after adjustment forpre-existing trends andthebroad

setofcovariates, ineach ofthesixyears subsequenttothe first certificationofa hospital for

Medicare

inthe county. This event study approach provides arigorous test ofthe integration hypothesis

—

thatblackpost-neonatal fatalities

were

causedby

racial discrimination in hospitalsand

that blacks' access tohospitals

was

restricted.An

immediate

and persistent intercept shiftwould

provide strong evidence infavor ofthe integration hypothesis. If instead the infant mortality and hospitalization rates

were

notassociated with certification, took a

number

of years tobecome

evident, evaporated soon aftercertification, or

began

prior to certification, the validity of the integration hypothesiswould

be undermined.''^

See DataAppendixfor adescriptionof

how

countieswereassignedMedicarecertification dates."

Both incomeandtransferpaymentsare interpolatedin missingyears. However,datacoverageisbestduringthe

periodofcertificationfortheMedicareprogram.

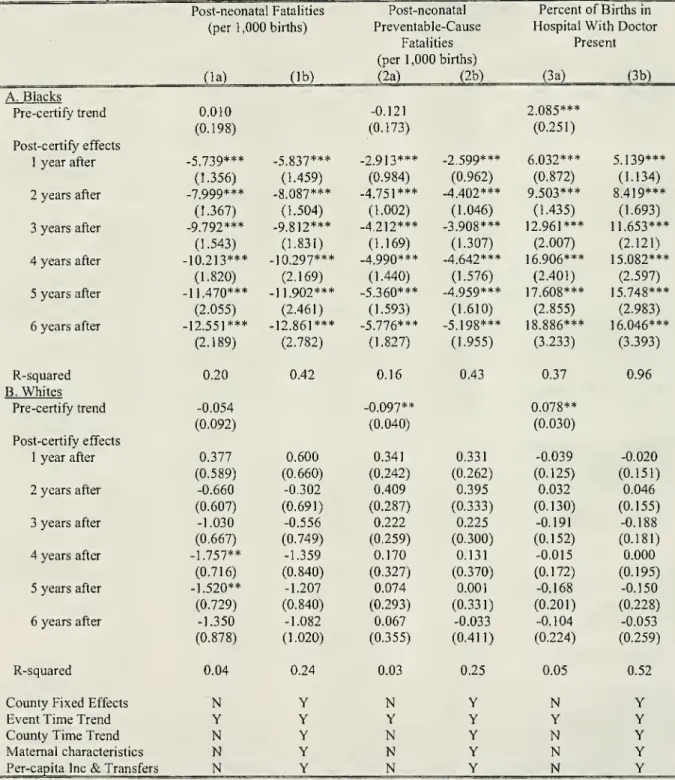

Table

4

presents the resultsfrom

fittingequation (2) forthe three dependentvariables. Itreportsresults

from

aparsimonious specificationthat includes just thetimetrendand

thesix 1(xct=

i) indicators,and

thefrillspecificationdescribedabove

(andintherow

headingsof Table4). PanelsA

and

B

give theresultsforblack

and

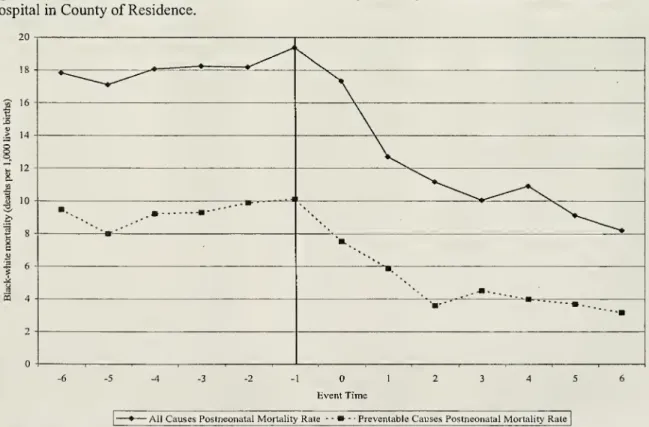

whiteinfants, respectively.Figure 3

summarizes

the post-neonatal mortality results graphically. Specifically, itis basedon

the estimationofaversionof equation(2) fortheblack-whitedifferenceinthepost-neonatal mortality for

all causes and, separately,preventablecauses.

The

specification'sonly covariates area fullset ofevent-timeindicators,

and

theirassociatedparametersareplotted.The

vertical line divides the yearsbeforeand

after

Medicare

certification.The

tableand

figure provide dramatic support for the integration hypothesis. There is littleevidence of a trend in either all cause or preventable cause post-neonatal mortality rates in the years

preceding

Medicare

certification. In the first year after certification, the black all cause post-neonatalmortahtyrate declined

by

about 6 deaths (per 1,000hve

births). This is greater than a25%

reduction intheblackpost-neonatality

mean

(for x=

0) ina single year.By

the end ofthe event-window, thedechne

is roughly 13 deaths (per 1,000 live births)

which

ismore

than a50%

decline.The

preventable causepost-neonatal mortalityrateestimatessuggestthatreductions inthesefatalitiesaccountedfor

40%)-45%

ofthe overall post-neonatal decline.

Notably, the adjustmentfor the full setofcovariateshas

no

substantiveimpacton

the estimatedcoefficients.^^ Thus, the observable relative risk characteristics of black mothers cannot explain the

column

(la) results.^' Further, the black-white differenceshown

in Figure 3 leads to nearly identicalconclusions;this

undermines

thepossibility that the introductionofa healthtechnology availabletobothraces or other secularshocksexplainthe results.

Finally,

columns

(3a)and

(3b) provide an opportunity to assess whether TitleVI

ofthe CivilRights

Act and

theMedicare

certifications achievedtheirmost

basic goalofincreasing blacks' accesstohospitals. Itistemptingto treatthe

measured

variableastheendogenous

variable inan equationforpost-'^The

additionof yearfixedeffects tothe richer specification incolumns (lb)and(2b) leadstothesamequalitative conclusions. However, thestandarderrorson theevent timeindicatorsaresubstantiallylargerduetothedifficulty

ofseparately identifying the year and event time fixed effectswith the modestvariation in Medicare certification dates.

^'

The

shareof black motherswho

wereteenagers orunmarriedincreasedinMississippiduringthelate 1950s.neonatal mortality (with certification as the instrument), but this

would

be inappropriate since thepercentageofbirths in ahospital

do

not directly affectdeaths inthepost-neonatal period, especiallythosedue to preventable causes."" Nevertheless, it is teUing that the entries

document

a largeand

preciselyestimated increase in the percentage of black births occurring in hospitals as

soon

asone

year afterMedicare

certification. Notably, therewas

a substantial pre-existingupward

trend in births in hospitalsamong

blacks.However, even

after accountingforthistrend,thepercentof blacksbom

inahospitalwas

more

than 12 percentagepoints(20percent)higherthreeyearsafter certification.B. AlternativeExplanations

For another factor to explain the post-neonatal mortality results, it

would

have

to exert animmediate

effecton

post-neonatal deaths (especiallyamong

preventable causes)and

vary acrossMississippi counties in the

same

way

as theMedicare

certification dates.These

aredemanding

criteria.Nevertheless, this subsection briefly considers alternative explanations for the paper's findings, in

particular the

major

changes in social welfareand

public healthprograms

resultingfrom

theWar

on

Poverty.

The

Medicaid

program, initiated in 1966, providedmoney

to poorer families for medical care.However,

Mississippi did not begin its participation inMedicaid

until January 1, 1970,by

which

timemost

ofthe reductions in black post-neonatal mortality in Mississippihad

already occurred. Similarly,overthis period the

AFDC

program

appears tohave

played amuch

smallerrole in Mississippi than inotherstates.'"

Moreover,

our event-studyestimates are essentiallyunchanged by

adjustment forcounty-leveltransferpayments,includingboth

AFDC

and

Food

Stamp

payments.''^Neither

do programs

that specifically targeted public health appear important for Mississippi'*"

We

attempted to obtain annual counts of infant admissions during the 1960s by race and age (along with

informationonthe principle diagnosis)fromseveralofthelargerMississippihospitals. Despiteouroffertobearthe

costof producingthese dataandredacting allpersonalidentifiers,ourrequestswererepeatedly denied.

'"

For example, caseloadsinMississippigrewatlessthan half the nationalratebetween 1965and 1970(Department

of Health and

Human

Services 1998:22). Accordingto theBEA's

governmenttransferpayments dataintheREIS

file,therewere nopayments fromthe

AFDC

programtoMississippiuntil after 1968. *'SeparateworkinprogressfindsthattheFood Stamps Program(FSP)nationalroll-outduringthelate 1960s and

early1970sdidimprovecertainperinatal outcomes(e.g. gestationlength). However, nodiscernibleeffectswere

foundforpost-neonatal mortality (whilenodistinguishablefromthezero, thepointestimateswerepositive,i.e.

FSP

associatedwithanincreasein

PNMR).

Moreover,noassociationwasfoundbetweencounty-leveladoptionofFSP

andbirths inhospital:

Almond

etal.(2006a).duringthisperiod. Real federalspending undertheMaternal

and

ChildHealth(MCH)

program

increasedonly 17 percent in Mississippi

between

1965and

1970(DHHS

2001:80),and

MCH

expenditures (perpoor

child) in Mississippiwere

less than half the national average in 1969 (Davisand

Schoen

1978:146).''^ Also, whilethe proliferationof

community

health centers duringthe 1970s hasbeen

foundto decreaseinfantmortality, especially

among

blacks, therewere

only 51 such centers inthe entirenationas of 1968

(Goldman

and

Grossman

1988). Further,community

health centers did not provide theaggressivemedical treatmentthat

would

havebeen

requiredby

infantswithpneumonia and

diarrhea.Finally, changes in birth technology

do

not coincide with the timing of the infant mortalityreductions forblacks in Mississippi (see footnote 22).

Moreover,

technological innovations are widelythought to impact early infant death resulting

from

prematureand

low

birth weight births,which

is notconsistent with the striking reduction in preventable post-neonatal infant deaths

among

blacks inMississippi.

In

summary,

we

areunabletoidentify a viablealternative explanation fortheevent studyresults.Our

conclusionfrom

the Mississippi data is that the federallymandated

integration of health carefacilities played a central role in the sharp decline in blacks' post-neonatal mortality rates.

To

put theresults in

some

context, the Table 3 estimates imply thatjust 6 years after successful integration,270

additionalblack post-neonatesperyear survivedtoage 1 inMississippi.

V. Interpretation

How

largewas

the mortality reduction causedby

mandated

integrationand

what

was

theassociated welfare gain?

Answering

these questions requires additional assumptions, but informs theimportance of the health effects here

documented and

how

theycompare

with effectsfrom

othergovernment

interventions.The

case for a causal impact ofmandated

integration is strongest in the rural South (whereex-ante access disparities

were

greatest)and

for causes of deathknown

to be treatable in hospitals.The

black-white preventable causepost-neonatal estimates in

column

(1)of Table 3 indicatea trend breakof0.66 deaths per 1,000 births lower in

1966

than predictedby

pre-existing trends, 1.32 per 1,000 births"•^

Refersto"Title

V

HealthProgramtotalsor theMCH

BlockGranttotals.'lowerin 1967,

and

soon untilitwas

6.6 deathsper 1000births lowerin 1975.The

multiplication ofthese declines in thePNMR

by

the annualnumber

of blackbirths in therural South implies that roughly 4,700 additional survived

from

age 1month

to age 1 year during theyears 1965-1975

and

25,300 infantsfrom

1965-2002.'*'' Alternatively, itmay

be reasonable toascribe theentire post-1965 trend break inpost-neonatal mortality (i.e. post-neonatal deaths

from

all causes) to themandated

integration. Inthis case,thesenumbers

would

rise to 7,100and

38,600, respectively.''^These

calculations suggest that the

mandated

integration of hospitals in the rural South accounted for16%

(based

on

preventable causes only) or25%

(basedon

all post-neonatal fatalities) ofthe national 7.5 per 1,000declineinthenationalblackPNMR

between

1965and

1975.An

alternativemeans

to assess themagnitude

ofthese gains is to askhow much

blacks in therural South

would

havebeen

willingtopay

(WTP)

forthese reductionsininfant mortality.''^To

developan estimate of

WTP, we

use Ashenfelterand

Greenstone's (2004) upperbound

estimate of $1.9 million(2005S)asthe valueofa statistical life(VSL)."*'

With

thisvalueand

a3%

discountrate,we

estimate thatblacks in the rural South in 1965

had

aWTP

for the reduction in infantmortality that occuiredbetween

1965 and 1975 of$7.3 billion (forpreventable cause post-neonatal fatalities)

and

$11.1 billion (for allcause post-neonatal mortality).

Among

all black residents ofthe rural South, theWTP

per

capitawas

$1,400and

$2,100 (for preventableand

all-causePNMR

reductions, respectively). Ifwe

keep thereduction inblackpost-neonatal deaths constantatthe 1975reduction for the

1975-2002

period, there areadditional gains of $20.1 billion (preventable causes)

and

$30.8 (allpost-neonatal causes) for the1975-^

Fortheyearsafter1975,we

holdthePNMR

reduction constantatthe 1975levelof6.6.per 1,000births.'*'

Alternativeassumptionswould causethesenumberstobeevenlarger. For example, it

may

beappropriatetousetheestimatesfromTable2thatrelyonthe 1955-65 period(ratherthan the 1960-65 periodas inTable3) toestimate the pre-1966 trend. Thetrendbreakestimates in Table 3 are largerbecause theblackpost-neonatal mortalityrate

worsened from 1955-1960, which is consistent with white resistance to the burgeoning Civil Rights

movement

(Garrow 1986 andCaro 2002). Additionally, itmight beappropriate to addthe reductioninthe black-white post-neonatal mortalityrateintheruralSouth,althoughthiseffect isn't statistically significant. Therewerealsopre-1965accessdisparities intheurban South so

some

may

considerit appropriateto addthe post-1965trendbreakin post-neonatal mortality. This argumentisundermined bythefindingofnotrendbreakinpreventable causes(seecolumn(2c)ofTable3). Our viewisthattheevidenceinfavorofattributingany

IMR

declines inother regionsisweak

duetotheabsenceof evidenceonex-ante accessdisparities,

''^

Obviously, this approach assumes the

WTP

waspositive only forblacks in the South and to the extent this isincorrect, willyieldconservative estimates.

"

Thisis atthelow end oftherangeofestimatesofthe

VSL,

butwe

thinkit is appropriateto beconservative forseveralreasonsincluding that thisestimatecomes frommorethan twodecades afterthe Civil Rights Act, blacks in

therural Southhadrelativelylowincomes,and

WTP

topreventaninfantdeathmay

belowerthanforanadultdeath(Murphyand Tope!2006).

2002

period(an additional/7ercapitagainof $3,900 and$5,900J.These

measures

ofWTP

for theimprovements

in infant mortality likely underestimate(potentially substantially) a

measure

ofWTP

for hospital integration. Integrationpresumably

reduced mortahty ratesamong

otherage groupsand

reducedmorbidities across all ages. Further, the practice ofsegregation

may

haveimposed

additional costs on hospitals thi-ough duplication ofservices.'*^On

theother side of the ledger, the

expanded

supply of health carepresumably

had

a social cost,and

a fullwelfare analysis

would

account for theseadded

costs. Itmay

also be appropriate to subtract theadministrative costsincurredinthe achievement ofintegration, althoughthey are likely to be a relatively

smallone-timecost.

VI.

Conclusions

Passage ofTitle

VI

ofthe Civil RightsAct

marked

a reversal offederal policy with respect torace. Inprohibiting discrimination

and

segregationin allinstitutionsreceiving federal funds,and

throughits vigorousenforcement

by

theJohnson

Administration, blackaccess to hospitals intherural Southwas

quickly

and

dramatically expanded, withlargebenefits interms ofinfant lives saved.We

conclude thatthe benefits of 1960s Civil Rights legislation extended

beyond

the labor marketand

therefore aresubstantially largerthanhas

been

recognizedpreviously.These

findings are relevant for current discussions regarding the efficient allocation of publicresources in developing countries.

More

than a third ofchildren inlow-income

countriesdo

not receivetreatment for acute respiratory infections and only half receive proper care for diarrhea (Jha et al.,

2002:2037). This paper illustrates that health treatments are sought out

when made

availableand

canhavelarge

and immediate

benefits."^Desegregation"requireslesspersonnel andcontributestotheefficiencyofthe hospitaliftherearenottwowaiting

rooms, two maternityunits, andtwo intensive careunits

~

oneforNegroesand one forwhites."(Nash 1968:249).Similarly,