Landscape, Western Madagascar)

Nasolo Rakotoarison, Thomas Mutschler and Urs ThalmannA visit to the Tsingy de Bemaraha in Western Madagascar was undertaken in 1991 to survey the lemurs of this little known reserve. Preliminary results of field observations and interviews with local inhabitants are presented together with notes on the forests, the human population and the conservation status of the region.

Introduction

The Reserve Naturelle Integrate Tsingy de Bemaraha is the largest reserve in Madagascar (1520 sq km) and has recently been classified as a World Heritage Landscape by UNESCO. The calcareous plateau of Bemaraha with its spectacular pinnacles (tsingy) in the southern part rises from about 100 m in the west to 850 m in the east, and drops precipitously to the valley of the Manambolo in the south. The cli-mate is seasonal, with rain from November to April and a dry season of 6-8 months. The mean annual temperature exceeds 26 °C (Nicoll and Langrand, 1989).

In 1990 two of us (TM, UT) discovered a population of Avahi (woolly lemur), which was provisionally identified as Avahi cf.

occi-dentalis (Mutschler and Thalmann, 1992;

tax-onomy for Avahi according to Rumpler et al., 1990). A follow-up visit was organized in 1991 to study this population in more detail and to carry out a survey of the lemur species, updat-ing the faunal list of Nicoll and Langrand (1989). The results of the lemur study are pre-sented here and the detailed results of the

Avahi study will be presented elsewhere

(Thalmann et al., unpubl. data).

Methods

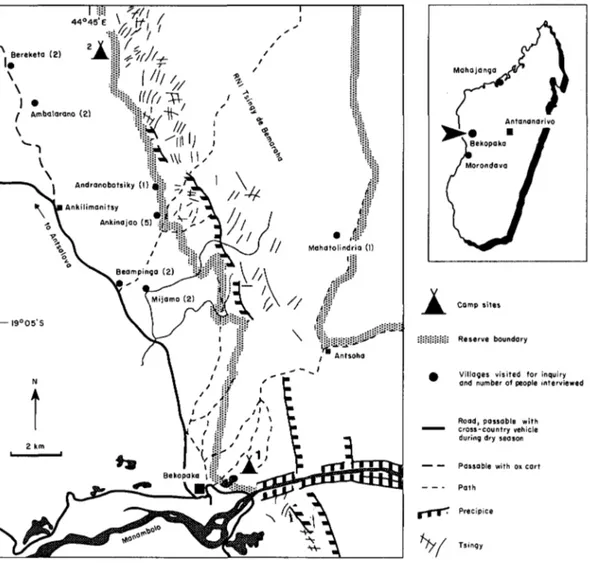

An initial flight over the southern part of the reserve yielded an overall impression of the vegetation and the extent of forests. Because

no car was available and public transport facilities do not exist in the study region, the ground survey was very limited. In order to look for Avahi, surveys on foot were carried out by day and night in a forest near Bekopaka (16-18 September) and in the sur-rounding forests of the camp site near Ambalarano (22 September-14 October, Figure 1). During these walks, other lemurs were often encountered. At night, headlamps and night-vision apparatus (Leica WILD BIG-3) were used to identify species.

Interviews were undertaken by one of us (NR) with our guide Monsieur Felix (7-10 October). Fifteen people from seven villages (Figure 1) were interviewed to collect informa-tion on local human inhabitants and their use of the forests as well as information about lemurs, particularly Avahi, Hapalemur and

Daubentonia.

Results

Human population

Each village had 10-50 inhabitants. Many peo-ple belong to the Sakalava du Menabe tribe, which was once politically dominant. A few consider themselves to be Vazimba, some-times believed to be a legendary tribe of Madagascar (e.g. Bradt, 1990; but see Sibree, 1915; Birkeli, 1936; Lombard, 1988). The Vazimba were the first people to settle in this region; the Sakalava immigrated later and 35

now there are immigrants from many other tribes: Antaimoro, Antandroy, Antanosy, and Bara from the south, Betsileo from the south-ern highland, and Korao from the south-east.

Forests

The forests are mainly of the western dry deciduous type, especially on the plateau. Two types of subhumid forest also occur close to the western precipice and in a number of depressions outside the reserve. At the end of the dry season, these forests are still green. The subhumid forest along the tsingy is an interrupted band along the western border of

the reserve. The main canopy reaches about 11 m with emergent trees of 15-22 m. The most frequent tree species are the litsake (Sytnphonia

sp.) and honofts-akoho (Mussenda laudia). Light

penetration is relatively high and the under-growth is correspondingly relatively dense. The second type of subhumid forest has a main canopy layer at a height of about 15 m, and emergent trees reach a height of 20-32 m. Light penetration is less effective and under-growth is very limited. In this forest the most frequent tree species are the ampolindmno

(IVepris sp.) and the rotsy (Eugenia sp.).

Most villages are within 2-5 km of a forest, which is used for cattle pasture, hunting

Mahoja Camp sites : & : • : • : • : • : • rrr

V

Reserve boundaryVillages visited for inquiry and number of people interviewed

Road, passable with Cross-country vehicle during dry season Passable with ox cart Path

Precipice Tsingy Figure 1. Map showing location and detail of study area (IGN, 1969).

(mainly birds and lemurs) and gathering (e.g. medical plants, honey), as well as a source of wood for fuel and construction of houses and cattle-pens.

Lemurs

Information on lemurs is summarized in Table 1. Nine lemur species were seen during our surveys. We failed to find Daubentonia, but its presence was reported by three local people. An unidentified species, with the local name of malagnira, was mentioned by two related people. Six lemur species were considered to be rare by one or several interviewees. Three species were said by people to be fady (=taboo) on at least one occasion: Propithecus verreauxi deckeni, Phaner furcifer, Mirza coquereli. In gen-eral, however, lemurs are not fady.

Daubentonia sp. The local name, bekapaky, describes the knocking sounds this animal makes. Of the three people reporting the beka-paky, one claimed to have seen it in the late 1960s in the Maromena forest within the reserve. When directly asked about the beka-paky, three further people said they knew the noise, and three reported that they had only heard stories about the animal.

Avahi cf. occidentalis. Dadintsifaky, the local name for this species, means grandparent of the sifaky. They are similar in appearance to Propithecus, but are believed to be older because they are darker and smaller.

Hapalemur g. occidentalis. The local name, bekola (be=big; fco/«=wound, also syphilis) refers to the glandular area on the inside upper arm, particularly well developed in males (Tattersall, 1982). Hapalemur is not valued as food because some local people fear that they could become infected with syphilis if they were to eat the animal.

Phaner furcifer. (Local name: tanta). Several people said that the meat of this species is bit-ter and repellent and they would not eat it. Propithecus v. deckeni. In addition to the well-ORYX VOL 27 NO 1 JANUARY 1993

A male woolly lemur {Avahi cf. occidentalis) from Bemaraha at a sleeping site during the day (Thomas Mutschler).

known belief that these lemurs (local name: sifaky) are the ancestors of mankind (e.g. in the Antandroy tribe), one person told a more detailed story. Once sifaky were human, but they were transformed into their present form because the 'tromba' (a bad ancestral spirit) entered their bodies. They are not hunted by people who believe this story because they fear that the 'tromba' will change host.

Malagnira. The malagnira is claimed to be sim-ilar to the tilintilivaha (Microcebus), but smaller and with different behaviour.

Discussion

Human population

Human population density in the region is still relatively low although up-to-date census

data are not available. The original inhabitants of the region are very hospitable, and immi-grants do not encounter many problems. Most immigrants come from the south, leaving regions that are increasingly threatened by drought. Population pressure is increasing and will probably accelerate in the future. By tradition, immigrants from the south are more likely to burn down the remaining accessible forests for agriculture and settlements, even within the reserve (H. Rabetaliana of UNDP, pers. comm.).

Forests

Access to some forests in the southern part of the reserve is difficult because of the tsingy. Wherever forests are accessible, especially along reserve boundaries and outside (although borders of the reserve are unclear, F. Busson of UNDP, pers. comm.), they are heavily threatened by deliberate burning. The subhumid forest along the reserve's western boundary has already been almost or com-pletely eliminated right up to the western precipice. It is possible that these partially evergreen forests serve as migration corridors for animals and as a refuge during the dry season, so disruption of the area is alarming. Furthermore, the subhumid forests represent

unusual plant associations within the western region, where most other forest trees are leaf-less between the end of July and the beginning of November (Koechlin et ah, 1974; Rohner and Sorg, 1989).

Lemurs

Published distribution maps (Petter et al., 1977; Tattersall, 1982) show eight species of lemurs for Bemaraha or nearby regions. In addition, Tattersall (1982) indicates a museum specimen of Avahi 200 km further south (Morondava). But the provenance of this speci-men cannot be confirmed (Mutschler and Thalmann, 1992). Nicoll and Langrand (1989) listed seven species for the reserve together with an additional species for a nearby region, again totalling eight species in all. Whereas it now seems very probable that Daubentonia occurs in the region (see also Petter and Andriatsarafara, 1987), our discovery of Avahi extends the known distribution range of the species more than 350 km to the south. There is some evidence that Avahi from Bemaraha differ from those of Ankarafantsika/ Ampijoroa near Mahajanga, but it is not yet clear at which taxonomic level.

Nine lemur species are definitely present in Bemaraha (Table 1), and it is probable that the

Table 1. Occurrence of lemur species at Bamaraha, based on surveys and interview results

Scientific name Microcebus murinus Propithecus verreauxi deckeni Lemur fuhus rufus Cheirogaleus medius

Hapalemur griseus occidentalis Phaner furcifer Lepilemur edwardsi Avahi cf. occidentalis Daubentonia sp. Unknown Mirza coquereli Vernacular name Tilintilivaha Sifaky Gidro Kelibehoy Bekola Tanta Boenga Dadintsifaky Bekapaky Malagnira Kifonjitsy SV + + + + + + + + -+ Interviews N 14 13 11 10 10 10 9 5+2* 3+6* 2 1 R 1 -8 1 2 -4 3 -F _ 2 -2 -1 ST A V R A V R R V E -V

SV, results of survey. Interviews: results include the number of local inhabitants reporting a species (N), con-sidering a species to be rare (R), and concon-sidering a species to be 'fady' (taboo, F). * Additional counts obtained by asking directly about these species. ST: conservation status according to IUCN (Harcourt and Thornback, 1990): A, abundant; V, vulnerable; R, rare; E, endangered.

occurrence of Daubentonia will be confirmed by sightings soon. We failed to confirm the presence of the malagnira. According to R. D. Martin (pers. comm.), Petter (1962), and Tattersall (1982), it is possible that two forms of Microcebus exist sympatrically in the west, but we did not pay special attention to this problem. There are, however, obvious differ-ences in Microcebus density. Near Camp 1,

Microcebus was one of the most frequently

spotted animals during each night walk. Near Camp 2, we first saw Microcebus only during the fifth night of intensive surveying, and never in such high frequencies as near Camp 1. We cannot provide an explanation for these differences.

The nine identified species, and possibly

Daubentonia, indicate a considerable diversity

of lemurs for a western biotope, where reliable data is available. Only seven species are known both in Kirindy (about 150 km to the south, across the rivers Manambolo and Tsiribihina), and in Ankarafantsika/Ampijoroa near Mahajanga (Nicoll and Langrand, 1989).

Daubentonia may also be present in

Ankarafantsika (Decary, 1950; Kaudern, 1915; Tattersall, 1982), but evidence is still weak.

Although lemurs are protected by national and international legislation (for details see Harcourt and Thornback, 1990), they are hunt-ed in considerable numbers in western Madagascar (Favre, 1989 unpubl. data, 1990). Nevertheless, habitat destruction through burning in order to gain new land for agricul-tural purposes is the most important threat, as is the case everywhere in Madagascar.

Conservation

The UNDP recently initiated a MAB project (Man and Biosphere) in the region, as proposed by Petter (1988). Meanwhile, a project base has been opened at Antsalova, an airstrip has been built near Bekopaka, and a second base at Bekopaka was planned for construction (R. Albignac, UNDP, pers. comm.) while this arti-cle was being written. Consequently, consider-able efforts are under way to preserve the whole region, including the RNI Tsingy de Bemaraha.

In addition to several other objectives, the project aims to promote 'ecological tourism'. Indirect advertisement has already started in popular magazines (e.g. Meister and Lanting, 1991) and on French TV (P. Schmid, pers. comm.). Excursions to Bekopaka are offered by travel agencies in Morondava, and public transport (taxi brousse) has reached Bekopaka twice a week since 1991. Nevertheless, virtual-ly no tourist facilities are present in Bekopaka and there are not enough guides. A Reserve Naturelle Integrate may only be visited by officials of the Water and Forest Department and scientists with permission from Malagasy governmental authorities. It is not possible to obtain permission in Bekopaka or in Morondava. There are obviously legal and socioecon-omic problems to be solved in developing the area for tourism. We sincerely hope that everybody involved will draw lessons from the events in Perinet-Andasibe during the 1980s. There, guides demanded exaggerated salaries (personal observations in 1987 and Bradt, 1990). Subsequently, one of them spent much money on alcohol. The sad story ended with the death of this once excellent and well-known young man (Bradt, 1990: 93). Development of tourism should be underta-ken very carefully, in order to avoid, as far as possible, any form of negative impact on either the social or ecological character of the region.

Acknowledgmen ts

We thank the Madagascar governmental institutions (MINESup, MRSTD, MPAEF), especially Madame Berthe Rakotosamimanana, for permission to con-duct this expedition. Very special thanks go to our guide Monsieur Felix and to Monsieur Ibrahim and his family, all from Bekopaka. We thank T. Geissmann and Prof. R. D. Martin for comments on the draft of the manuscript. The expedition was materially and financially supported by: A. H. Schultz-Foundation, anonymous contributions, G. and A. Claraz-Donation, Leica Heerbrugg Ltd., Rentenanstalt Insurance's, Swiss Academy of Science, Vontobel Holding Ltd., Zoological Society of Zurich.

References

Birkeli, E. 1936. Les Vazimba de la cote ouest de Madagascar. Mem. Acad. Malgache, 22,1—67.

Bradt, H. 1990. Guide to Madagascar, 2nd edn. Bucks (UK) and Edison (USA): Bradt (UK) and Hunter (USA).

Decary, R. 1950. La Faune Malgache. Payot, Paris. Favre, J.-C. 1989. Unpubl. Essai a"estimation de la

valeur economique de la foret dense seche de la region de Morondava (Madagascar) selon different modes de mise en valeur. Travail de diplome, Ecole Polytechnique Federal Zurich, Switzerland. Favre, J.-C. 1990. Evaluations qualitatives et

quanti-tatives des utilisations villageoises des ressources naturelles en foret dense seche - etude de cas du village Marofandilia dans la region de Morondava/Madagascar. Dept. fur Wald- und Holzforschung ETH Zurich, Arbeitsberichte Internationale Reihe, 90 (4), 1-59.

Harcourt, C. and Thornback, J. 1990. Lemurs of Madagascar and the Comoros. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

IGN. 1969. Carte de Madagascar au 1/100 00 -Feuille G-47. Antananarivo: Institut Geographique National, Centre a Madagascar.

Kaudern, W. 1915. Saugetiere aus Madagaskar. Ark. Zoo/. 9(18), 1-101.

Koechlin, J., Guillaumet, J.-L. and Morat, P. 1974. Flore et Vegetation de Madagascar. J. Cramer, Vaduz.

Lombard, J. 1988. Le royaume Sakalava du Menabe-Essai d'analyse d'un systeme politique a Madagascar. Editions ORSTOM, Paris.

Meister, M. and Lanting, F. 1991. Experiment Madagaskar. Geo, 1991 (11), 165-192.

Mutschler, T. and Thalmann, U. 1992. Sighting of Avahi (woolly lemur) in western Madagascar. Primate Conservation, 11.

Nicoll, M.E. and Langrand, O. 1989. Madagascar: Revue de la conservation et des aires protegees. WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

Petter, J.-J. 1962. Recherches sur 1'ecologie et l'ethologie des lemuriens malgaches. Mem. Mus Natn. Histoire Nat., Serie A, Zoologie, 27,1-146. Petter, J.-J. 1988. La conservation des forets

naturelles dans la region de Morondava. In

L'Equilibre des Ecosystemes forestiers a Madagascar: Actes d'un seminaire international (eds L. Rakotavao, V. Barre and J. Sayer), pp. 274-277. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. Petter, J.-J., Albignac, R. and Rumpler, Y. 1977.

Mammiferes Lemuriens (Primates Prosimiens). ORSTOM/CNRS, Paris.

Petter, J.-J. and Andriatsarafara, S. 1987. Les lemuriens de l'ouest de Madagascar. In Priorites en matiere de conservation des especes a Madagascar (eds R. A. Mittermeier, L. H. Rakotovao, V. Randrianasolo, E. J. Sterling and D. Devitre), pp. 71-73. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Rohner, U. and Sorg, J.-P. 1989. Observations phenologiques en foret dense seche. 2 Tomes. (2nd edn.). Centre de Formation Professionnelle Forestiere 'Fofampiala', Morondava.

Rumpler, Y., Warter, S., Rabarivola, C, Petter, J.-J. and Dutrillaux, B. 1990. Chromosomal evolution in Malagasy lemurs: XII. Chromosomal banding study of Avahi laniger occidentalis (Syn: Lichanotus laniger occidentalis) and cytogenetic data in favour of its classification in a species apart - Avahi occi-dentalis. Amer. J. Primatol. 21,307-316.

Sibree, J. 1915. A Naturalist in Madagascar. Seeley, Service & Co Ltd, London.

Tattersall, I. 1982. The Primates of Madagascar. Columbia University Press, New York.

Thalmann, U., Geissmann, T., Mutschler, T. and Rakotoarison, N. Unpubl. Field observations on a recently discovered population of Avahi (woolly lemur) in western Madagascar.

Nasolo Rakotoarison, Laboratoire de Zoologie, Pare Botanique et Zoologique de Tsimbazaza, BP 4096, Antananarivo 101, Madagascar.

Thomas Mutschler and Urs Thalmann, Anthropological Institute and Museum, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstr. 190, CH-8057 Zurich, Switzerland.