Branching Out into Immigrant Neighborhoods: How Public Libraries Distribute Community Resources to Meet Immigrant Needs

by

Laura Humm Delgado Bachelor of Arts Williams College

Williamstown, Massachusetts (2005) Master in City Planning

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts (2010)

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy in Urban and Regional Planning at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 2020

© 2020 Laura Humm Delgado. All Rights Reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created.

Author_________________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 20, 2020 Certified by _____________________________________________________________ Professor Emeritus Phillip Clay Department of Urban Studies and Planning Dissertation Supervisor Accepted by_____________________________________________________________ Associate Professor Jinhua Zhao Chair, PhD Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Branching Out into Immigrant Neighborhoods: How Public Libraries Distribute Community Resources to Meet Immigrant Needs

by Laura Humm Delgado

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 20, 2020 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy in Urban and Regional Planning ABSTRACT

Local organizations play a critical role in providing access to resources and opportunities for those who are low-income, socially isolated, or marginalized. This is especially true for immigrants in the United States, where support with integration falls almost entirely on local organizations.

Immigrants are more likely to live in poverty; yet, they are accessing the social safety net less for fear of discrimination and deportation. This research asks how one type of local organization, the neighborhood library branch, distributes resources to immigrants across urban neighborhoods and how neighborhoods shape organizational resources.

I approach this research through a mixed-method study of the Boston Public Library and its twenty-five neighborhood branches that relies on participant observation, interviews, and the analysis of archives, texts, and public library data. The first part uses an immigrant integration framework to examine how neighborhood branches contribute to English language learning and political,

economic, and social integration. I address how immigrant services align with neighborhood needs and to what extent immigrants access these resources. I find that institutional resources are well targeted to immigrant neighborhoods, but community resources are more effective at reaching immigrants and provide intangible benefits that are tailored to neighborhoods. A reliance on community resources, however, can exacerbate inequalities across neighborhoods. The second part of this research addresses how the neighborhoods in which neighborhood branches are located shape library resources through 1) expressed community needs, 2) level of volunteerism, 3) cultural sharing practices, and 4) organizational partnerships.

Whereas scholars have addressed the question of how organizations provide access to resources for marginalized populations by looking at the geographic distribution of organizations, institutional funding, and brokered resources, this research asks 1) how neighborhoods shape organizational resources and 2) what factors, beyond geographic proximity, affect access to resources. The findings from this research have implications for how scholars and planners conceptualize and identify organizational resources at the neighborhood level. Additionally, this research offers lessons for what practices local organizations and government agencies can adopt to reach immigrant

communities at a time when immigrants are becoming increasingly fearful of accessing government institutions, public benefits, and public spaces.

Dissertation Supervisor: Phillip Clay Title: Professor Emeritus

Acknowledgements

I am so grateful to have had a supportive, considerate, and knowledgeable committee who helped me tremendously with both my qualifying exams and my dissertation. Professors Phillip Clay, Justin Steil, and Roberto Fernandez, I have learned so much from each of you about what it means to do research and to mentor students with kindness, integrity, and compassion. Professor Clay, thank you so much for teaching me about research and helping me to move forward and complete the doctoral program while also being so kind and encouraging along the way. I am very lucky that I started the doctoral program as your advisee and that you stuck with me even after retirement. Every doctoral student should be so lucky to have an advisor, chair, and mentor such as you! Professor Steil, I am so grateful that you came to DUSP when you did. Your concern for your students and the way that you bring social justice into your research and teaching are inspirational. Thank you so much for the guidance, support, and encouragement you provided throughout my time at DUSP and for showing me how to do research and teach! Professor Fernandez, thank you very much for coming across campus to be on my exam and dissertation committees! You are an impressive scholar, and I am so grateful for the knowledge and expertise you’ve shared with me. From our first meeting through my dissertation defense, I have really appreciated how you have tried to ground my doctoral work such that it leads to a long-term academic career.

Thank you to Garnette Cadogan and Chris Bourg for supporting my love of libraries and this dissertation! Garnette, though you were not officially on my dissertation committee, you have been such an important mentor throughout! I am so lucky to have benefited from your knowledge and enthusiasm for libraries these past few years. I selected a somewhat less traditional dissertation topic, and you helped to keep me focused and excited about it throughout. Chris, thank you for the time you have taken to help me with this dissertation, for your encouragement, and for sharing your expertise and passion regarding libraries!

MIT and DUSP, in particular, has been an amazing place at which to study as both a master’s and a doctoral student. I am very grateful to the many faculty members who have made learning exciting and who have been so supportive. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to learn from you as a student, a researcher, and a teaching assistant! To Ellen Rushman, Sandy Wellford, Karen Yegian and all of the other staff members who have been so helpful, kind, and supportive throughout, thank you so much! You make DUSP run like a well-oiled machine, and you bring a lot of heart to the department.

Thank you to my PhD cohort and to the many friends I have made along the way. Aditi Mehta, thanks for being my best friend in the MCP and PhD program! Can we please find a way to work at the same place for many years to come? To Melissa Chinchilla, Aria Finkelstein, Ella Kim, Haegi Kwon, Prassanna Raman, and Yasmin Zaepoor, I am so lucky to have shared this experience (and an office at some point!) with each of you! I hope our paths continue to cross. Finally, I am so grateful to have encountered many impressive, dedicated, and impassioned MCPs (too many to list!) throughout these many years at DUSP. I have always thought that it is too bad that you all come and go so fast, but I am particularly grateful to have gotten to know many of you.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of this research was having the excuse to talk with librarians across the Boston Public Library last summer. Each was impressive, intelligent, caring, passionate, and a joy to talk with. As I finished this dissertation, I reached back out to the librarians, and it so happened that the COVID-19 cases in Massachusetts were peaking when I did. I was so touched, and yet not surprised, by how warm their responses were. Thank you so much to all of the BPL librarians who generously took the time to talk with me! I wish I had the opportunity to work with all of you on a regular basis. I know you were busy when I reached out to you, and I am truly grateful for the time, thought, and care that you put into our interviews. It has been so wonderful to talk with all of you and see how devoted you are to your patrons, the work you do, and making the world a better place. The work you do takes time, expertise, and compassion, and I am very humbled by each of you. THANK YOU!

Thank you very much to the many other people who have taken the time to meet and talk with me about libraries! Maria Balestrieri, Chris Bourg, and Jan Seymour-Ford, thank you so much for pre-testing my interview schedule. Your feedback was invaluable! Thank you, also, to John Dorsey, Glenn Ferdman, Priscilla Foley, David Giles, Valerie Karno, Eric Klinenberg, David Leonard, Maria McCauley, Shelley Quezada, Jessamyn West, and Jason Yee. Each of you has been so helpful talking with me and providing invaluable information about public libraries.

Thank you, also, to the Ford Foundation, the Boston Area Research Initiative, the Bill Mitchell ++ Fund, and MIT for generously funding this research! I could not have done it without these sources of support.

* * *

A lot can happen during the time it takes to graduate from a doctoral program, and I am so grateful to have gained a partner and son and to have been able to live close to my family throughout most of it. I have relied on my growing family for companionship, laughs, food, support, guidance, and encouragement. The dinners, brunches, walks, movies, and vacations spent with all of you—Doug, Barbara, Mommy, Daddy, Oliver, and even Clem, our dog—mean the world to me and always will. Thank you, also, to my wonderful aunts, uncles, cousins, and in-laws, who have been so supportive throughout!

To Oliver, thank you for coming into our lives as I was writing this dissertation. Your smiles, giggles, and love of life are infectious, and you helped remind me what is important in life. Thank you, also, for coming to my virtual dissertation defense! I will always remember seeing your amazing, curious, little face on the screen. I love you with all my heart, and I cannot wait to see what excites you in life and to learn with you!

To Doug, thank you for your love, support, encouragement, and sense of humor! I am so grateful to go through life by your side, always learning, exploring, laughing, and growing together. We’ve always spent a lot of time together working from home, but having to do so during a pandemic with just a few walks here and there really reinforced how much I love being with you. I love you just as much when we are raising an infant during a global pandemic as I do when life feels like a vacation. I cannot wait until Oliver, you, and I can seek out adventures in the mountains of Vermont with our bikes and kayaks in tow!

To Barbara, thank you for being the most amazing and supportive sister that I could ever ask for! You are always so good to Doug, Oliver, Clem, and me, and you are the sweetest, most fun person I know. I am most definitely jealous of your boogie! Thank you, also, for welcoming Oliver into the family with love and compassion. He is so lucky to have you as his aunt! With my newfound time, I look forward to baking and cooking with you, more walks together, and talking with you every single day. I love you so much and always will!

To Mommy and Daddy, thank you for always believing in me, for teaching me how to do research from a young age, for encouraging me to do volunteer work, and for showing me what it means to be an academic and advocate with heart. Thank you for first introducing me to public libraries and for fostering a love of libraries along the way. I love you very much and am so grateful for the many hours spent talking about teaching and research with you, for the child care you provided during the first few months of Oliver’s life, for the many meals and groceries you have shared with us, for the daily phone calls, and for every other way in which you have sustained and loved me! You lead by example in all ways, and I hope I become as good a parent to Oliver as you have been to Barbara and me.

Table of Contents

List of tables and figures ... 9

Chapter one | Introduction ... 10

Introduction ... 10

Theoretical framework: Concentrated poverty, segregation, and organizational resources ... 13

Are low-income neighborhoods, in fact, lacking organizational resources? ... 15

Measuring access: Beyond geographic proximity and institutional resources ... 19

Why immigrants and public libraries? ... 23

Research questions ... 28

Dissertation structure ... 29

Chapter two | Literature review: Immigrants, access to opportunity, and public libraries ... 30

Introduction ... 30

Immigrant integration ... 31

The immigrant social safety net ... 40

Barriers to accessing organizational services ... 43

Public libraries and immigrant integration ... 45

Conclusion ... 55

Chapter three | Context and methodology ... 57

Introduction ... 57

Context ... 59

Data collection and analysis ... 76

Chapter four | Meeting immigrants where they are: Access to immigrant programs and services across neighborhood library branches ... 85

Introduction ... 85

The neighborhood branches and their neighborhoods ... 87

Immigrant programs and services ... 91

The geographic distribution of immigrant services and programs ... 106

Beyond geographic access: How immigrants are accessing immigrant programs ... 113

Conclusion ... 122

Chapter Five | The community is the collection: How neighborhoods shape the distribution of resources across neighborhood library branches ... 125

Introduction ... 125

Level of volunteerism ... 132

Cultural sharing practices ... 137

Organizational partnerships ... 141

Conclusion ... 149

Chapter Six | Conclusion ... 151

Introduction ... 151

Summary of findings ... 152

Implications for theory ... 153

Implications for policy and practice ... 161

Conclusion: Learning from public libraries ... 168

Appendix A | Interview schedule ... 170

Appendix B | List of programs and events attended ... 177

Appendix C | Sample branch librarian job description ... 178

List of tables and figures

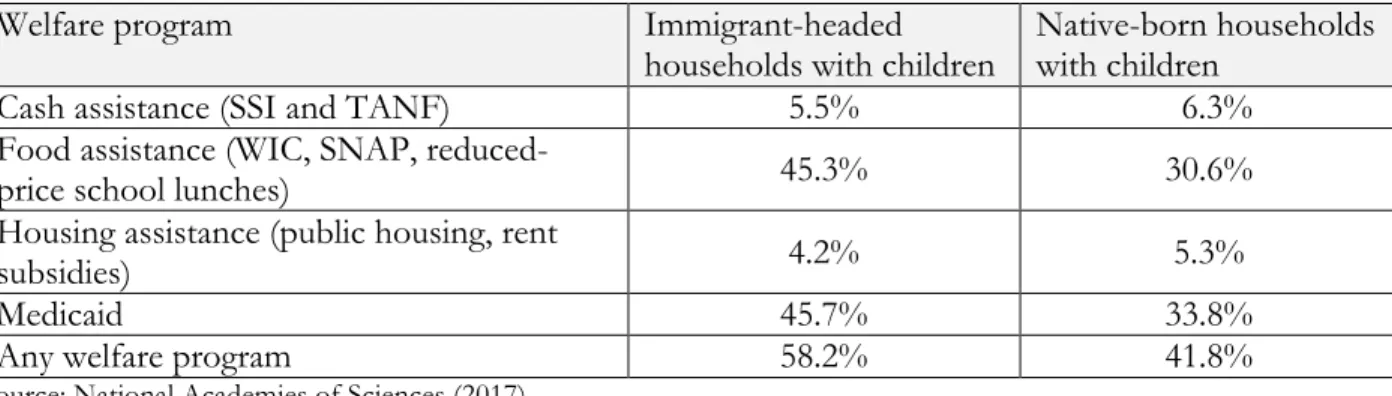

Table 1 Welfare utilization rates in the United States ... 41

Table 2 BPL neighborhood branch usage, FY2019 ... 73

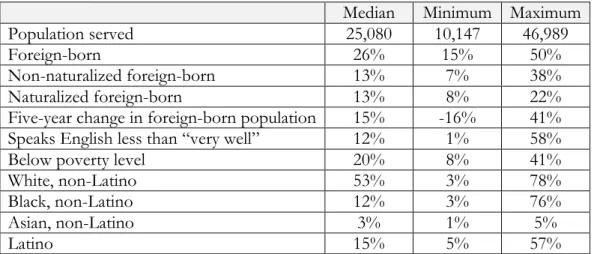

Table 3 Neighborhood characteristics of BPL neighborhood branches, 2017 ... 73

Table 4 BPL neighborhood branch data accessed ... 80

Table 5 Programs by immigrant integration indicator ... 106

Table 6 Neighborhood characteristics of branches offering immigrant programs ... 108

Table 7 Concentration of immigrant programs within neighborhood branches ... 112

Table 8 Immigrant access to programs ... 114

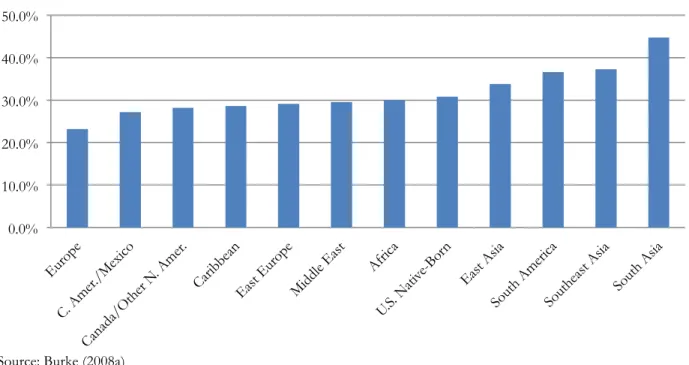

Figure 1 U.S. household member used a public library in the past month by region of origin ... 46

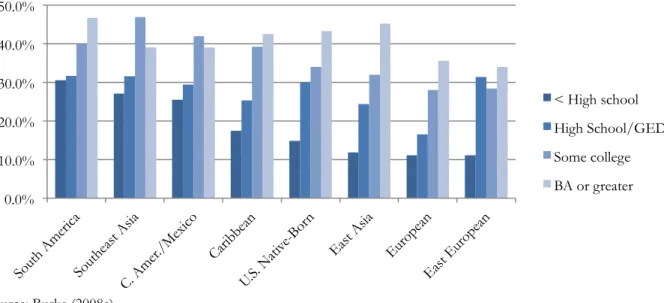

Figure 2 U.S. household used a public library in the past month by region of origin and education level of respondent ... 47

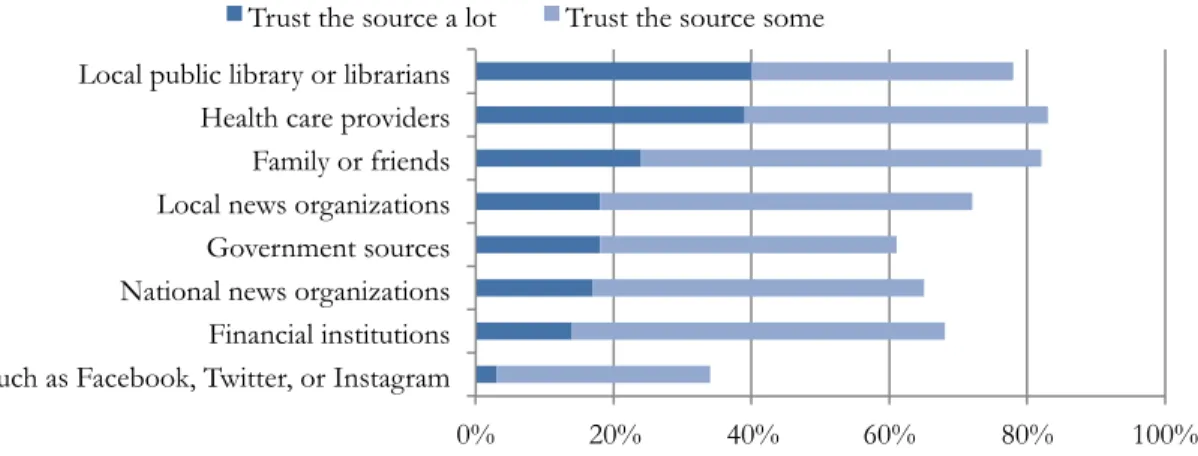

Figure 3 Adults who trust information from different sources ... 53

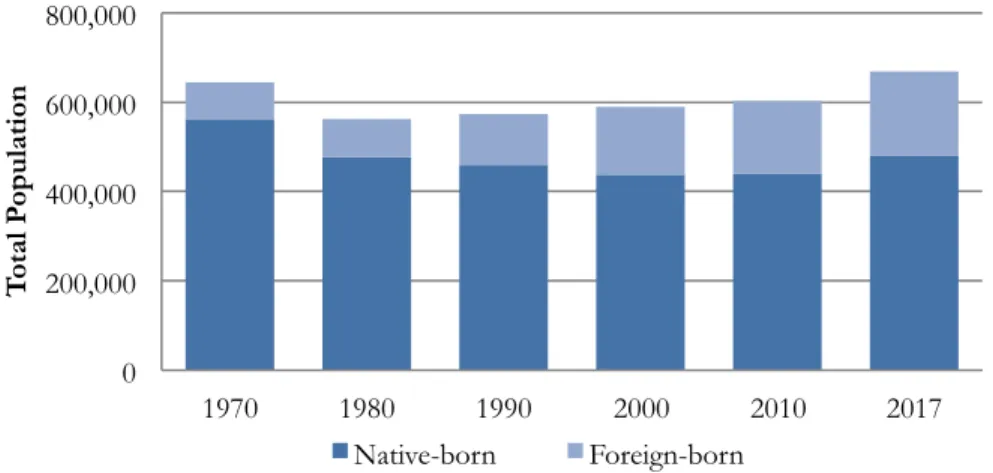

Figure 4 Immigration in Boston, 1970-2017 ... 60

Figure 5 Socioeconomic characteristics of Boston’s population, 2017 ... 61

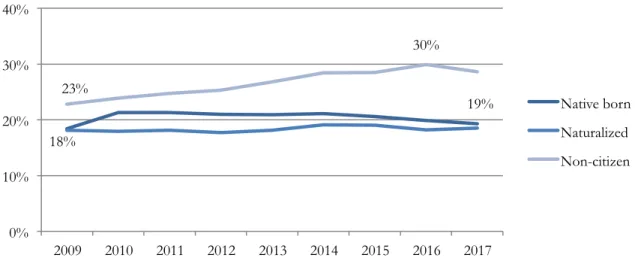

Figure 6 Poverty rate of Boston’s population by immigration status, 2009-2017 ... 62

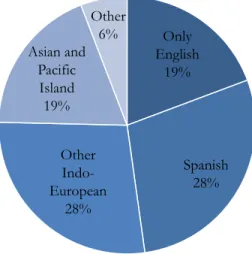

Figure 7 Languages spoken by Boston’s immigrant population, 2017 ... 63

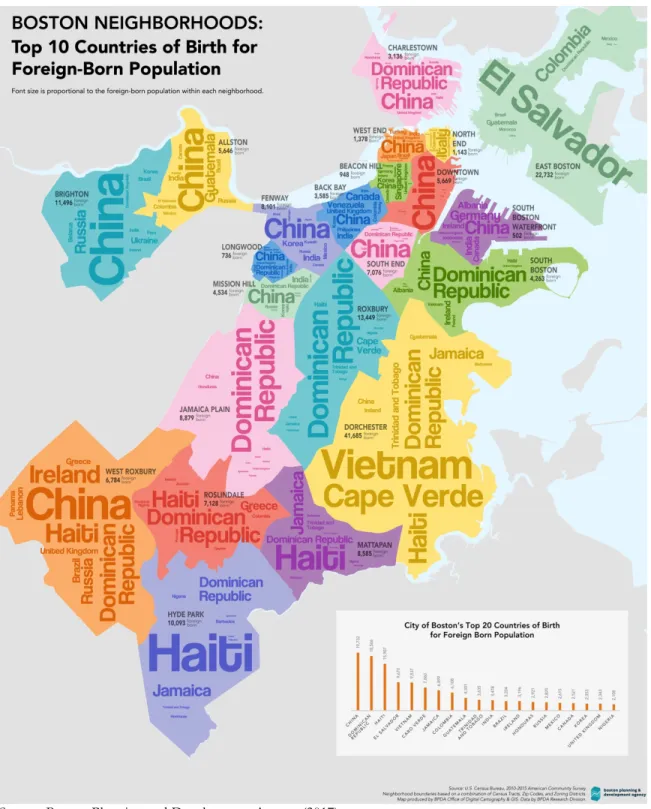

Figure 8 Boston’s neighborhood populations by country of origin ... 64

Figure 9 Map of the BPL's neighborhood branches and central branch ... 75

Figure 10 Re-opening of the Jamaica Plain Branch and opening of the Chinatown Branch ... 78

Figure 11 BPL programs and attendance, FY 2004-2019 ... 89

Figure 12 Immigrant Information Corner at a neighborhood branch ... 94

Chapter one | Introduction

Introduction

On a late November afternoon in 2015, immigrants from countries around the world

gathered with native-born neighbors in a heavily Latinx neighborhood of Boston to celebrate Arabic culture at their local public library. They gathered in a festively decorated room with flags and photos from Arab countries on the walls and traditional clothing and serving dishes on display. Women and men, young and old, from a variety of backgrounds shared home-cooked Arabic food and indulged in pastries from a local Moroccan bakery. Children showed off their new henna tattoos and strung beads. This event emerged organically from the initiative of community

members, bridged diverse populations, and created a safe public space in which the Arab community could convene and celebrate their culture with others.

The value of this event for the local immigrant and native-born community is undeniable, yet a traditional study of organizational resources would likely overlook it. No formal organization ran this event; instead, an informal group of female library patrons organized it in the library space. Neither government grants nor nonprofit funding paid for it; rather, it came together through community volunteers, a donation from a local bakery, and a small food budget from the library. The benefits of the event cannot be easily measured or quantified, but it created value in its

community. Additionally, this event was unique to its neighborhood of Latinx and Arab residents, and one might argue that it could not have been so successful, or even have taken place, in any other Boston neighborhood. This community-led cultural event provides an example of how local

organizations connect individuals to resources in nontraditional ways and how communities have the power to shape organizational resources from the ground up.

For better or worse, organizations determine our ability to access services, material goods, information, and social supports. As a society, we get by and get ahead through organizations. They broker resources for those in need and create a social infrastructure that benefits all (Klinenberg 2018; Putnam 2000; Small 2009). This is especially true for those who are socioeconomically

marginalized and socially isolated (Allard and Small 2013). Whereas those who have higher incomes and greater wealth may rely on local organizations for their employment, health care, and children’s schools, those who are low-income must also turn to local organizations for housing support, food, child care, legal aid, and other basic needs that they cannot necessarily afford to purchase. For those without social support networks, organizations may provide the only point of access to such

resources in times of need (Klinenberg 2002). Local organizations can provide a safety net that helps to address inequalities and protect against socioeconomic shocks, but they must be accessible to populations in need to do so.

Given the importance of public and private organizations for addressing poverty, isolation, and marginalization, the question arises as to how well organizations manage to allocate services to those most in need. Are organizations and the resources they offer geographically situated such that they serve those most in need? Are they accessible to diverse populations? How do organizational resources vary across neighborhoods in relation to local needs? Do low-income neighborhoods lack sufficient organizational resources? What about poor neighborhoods of color and immigrant neighborhoods? To what extent do organizational resources adjust over time to meet new and evolving community needs? How, if at all, do neighborhoods—through their structures, institutions, resources, and people—shape the availability of organizational resources?

This dissertation examines immigrant services in public libraries to address the question of how access to organizational resources varies across neighborhoods and to what extent

what mechanisms, if any, neighborhoods shape the availability of organizational resources. In contrast to existing literature, I look at measures of access that go beyond geographic proximity, focus on organizations that experience uniform institutional supports and pressures, and consider non-monetary community resources.

Non-naturalized immigrants are an increasingly vulnerable population because they are more likely to live in poverty and experience linguistic and social isolation, the public supports available to them are declining, and they face mounting risks and fears when accessing public spaces and

benefits. Public library branches offer a unique lens through which to study how organizational resources and access vary for immigrants across neighborhoods. They are the only organization that is free and open to all,1 and they have a long history of serving immigrant populations (Jones Jr. 1999). At the same time, they are not immune to anti-immigrant activism, and some even have faced pressure to eliminate foreign language collections and immigrant services (Cuban 2007; Harrington 2012; The Associated Press 2005). Public library branches are part of bureaucratic government institutions, but they maintain discretion in regards to the types of programs they offer, how they do community outreach, and how they adapt their environments and practices to serve various populations, including immigrants. This discretion and flexibility allow public libraries to continually adapt their services and programs to immigrant needs as those needs evolve with new waves of immigration and federal policy changes.

For these reasons, I focus this research on public library branches to study how immigrant access to organizational resources varies across neighborhoods and what role local neighborhoods play in shaping access and resources. In doing so, I also address how public library branches engage

1 Many public organizations are free, but they are only open to those who meet certain qualifications. For example, public schools are open to all who are within a specified age range. Other public and private organizations, such as community centers, gyms, and businesses, are open to all, but they are not free. Public parks, on the other hand, are free and open to all, but they are not organizations. 2 As of 2017, 14.2% of the native-born population, 11.1% of naturalized citizens, and 22.9% of non-naturalized immigrants lived below the poverty level in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau 2017).

with the immigrant integration process at the local level. Immigrant integration is a two-way process of mutual adaptation, and public libraries participate in a few key aspects of immigrant integration: English language proficiency, political participation, social interaction, and, to a somewhat lesser extent, socioeconomic attainment. For example, the Arabic Day event discussed above created an opportunity for local immigrants and the library community, which consisted of native and foreign-born residents, to celebrate, socialize, and learn about Arab cultures. At other times, immigrants turn to public libraries for help with computers, job applications, and public benefits. In some neighborhoods, they bring their children and grandchildren to bilingual story hours that allow for cultural sharing within families. Just as neighborhoods are unique, so are the communities of immigrants that neighborhood library branches serve. Moreover, these communities bring to neighborhood library branches unique and valuable resources that benefit both immigrants and native-born residents.

Theoretical framework: Concentrated poverty, segregation, and organizational resources For decades, scholars have explored the question of how concentrated poverty and racial segregation affect the distribution of organizational resources across marginalized neighborhoods. William Julius Wilson (1987) introduced deinstitutionalization theory, which posits that concentrated poverty leads to social isolation and the closure of basic institutions, such as stores, churches, and schools. According to Wilson, as middle-class households move out of urban neighborhoods, thereby concentrating poverty, they also take with them the buying power and leadership necessary to support local institutions. Even when institutions remain, they may lack access to resources and leadership. The result is increased poverty, social isolation, and deinstitutionalization, all of which compound the negative effects of living in poverty. By focusing on socioeconomic status and

market forces, though, deinstitutionalization theory largely ignores the role of segregation, racism, and political capital.

In contrast to Wilson’s deinstitutionalization theory, some scholars have proposed that poor, segregated neighborhoods have fewer institutional resources because of political dynamics, as

opposed to market forces. These scholars theorize that discriminatory practices that lead to racially segregated, high poverty neighborhoods create marginalized communities that lack the political capital necessary to attract, demand, and retain resources (Logan 1978; Logan and Molotch 1987). Meanwhile, affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods are able to use their political clout to secure more institutional resources and maintain their privileged position. Public schools in affluent areas provide a good example of this. In these schools, parents volunteer their time, donate

resources, and lobby for additional resources from the public school system. These actions, along with limited public resources, can then lead to a redistribution of public resources towards schools in more affluent neighborhoods and away from schools in low-income neighborhoods (Cucchiara 2013).

Finally, other scholars have proposed that low-income neighborhoods are not necessarily deprived of institutional resources. This neighborhood revitalization perspective theorizes that low-income neighborhoods will actually have more institutional resources that derive from the public sector. According to Lester Salamon (1987), the nonprofit sector responds to market failures, and the government steps in when there are failures in the nonprofit sector. This perspective sees government’s role as meeting population needs, often through local organizations. Thus, as local needs grow, so will public resources for nonprofit organizations. Still, other organizational factors, such as culture, leadership, and capacity, may distort this relationship between the state and

nonprofit organizations. Furthermore, in the current day, organizations rarely rely solely on public funding; instead, they must piece together funding from a variety of sources.

Are low-income neighborhoods, in fact, lacking organizational resources?

A convincing argument can be made for all three theories, but which theory is borne out in the data? Do low-income neighborhoods have fewer, equivalent, or more organizational resources compared to higher-income neighborhoods? Of course, not all organizations are equally desirable within neighborhoods, so more is not necessarily better. For example, communities may view day care centers and public libraries as assets and homeless shelters and substance abuse services as liabilities. Keeping this in mind, scholars have sought to answer the question of how aligned

organizations are with neighborhood need by using data from different types of organizations across a variety of urban contexts. As it turns out, the answer is: it depends. It depends on the type of organization, whether the organization is public or private, what the racial composition of the neighborhood is, and how the city as a whole is structured.

More often than not, socioeconomic status alone does not lead to fewer organizations at the neighborhood level, and it is sometimes associated with more organizations. This suggests that there is support for the neighborhood revitalization perspective that predicts more services in low-income areas. In regards to urban services, such as schools, libraries, police and fire stations, and mental health services, there is little difference between the number located in low-income

neighborhoods and high-income neighborhoods. When there is a difference, it leans towards there being more urban services, such as public schools, churches, and social service agencies, in low-income neighborhoods (Marwell and Gullickson 2013; Oakley and Logan 2007). In regards to organizations for children, low-income neighborhoods are more likely to house public schools and publicly funded child care centers, but they are less likely to have private schools and child care centers (Oakley and Logan 2007; Small and Stark 2005). Additionally, neighborhood poverty is associated with increased financial resources for nonprofit organizations. Local nonprofit social service agencies are more likely to receive public funding if they are located in socioeconomically

disadvantaged neighborhoods (Marwell and Gullickson 2013), and child care centers in low-income areas have more referral and collaborative ties than their counterparts in higher-income areas (Small 2009).

One might expect support for deinstitutionalization theory when it comes to for-profit businesses since they, like private schools and child care centers, rely on the spending power of local residents. To the contrary, poor neighborhoods may be less likely to have a couple of types of businesses, such as banks and grooming stores, but they are actually more likely to have hardware stores, grocery stores, convenience stores, pharmacies, credit unions, restaurants, and laundries (Small and McDermott 2006). This suggests that lower buying power in poor neighborhoods does not necessarily result in fewer organizational resources.

As the above research demonstrates, scholars have found generally positive relationships between neighborhood poverty and access to public and private organizations, but the picture changes when racial composition is factored in. There is overwhelming evidence that black, in particular, as well as Latinx and Asian neighborhoods have less access to public and private organizational resources than their white counterparts. For example, whereas Mario Small and Monica McDermott (2006) find a positive relationship between neighborhood poverty and for-profit establishments, they also find that the proportion of black residents is consistently associated with fewer commercial establishments. Similarly, Kathryn Freeman Anderson (2017) finds a positive relationship between the availability of health-related organizations and neighborhood poverty, but a negative relationship between black neighborhoods and some health-related organizations, such as restaurants, pharmacies, civic associations, and social services agencies. Moreover, neighborhood poverty amplifies this negative relationship between black neighborhoods and health-related organizations.

Research shows a similarly negative relationship between publicly-funded organizations and populations of color (Allard 2008). Nonprofits are more likely to receive government funding as neighborhood poverty increases, but this only holds true in white neighborhoods. Black

neighborhoods are actually less likely to receive government funding as neighborhood poverty increases (Garrow 2014). The process of “white flight,” whereby white residents move out and neighborhoods become increasingly of color, is also associated with a decline in nonprofit organizations (Garrow and Garrow 2014). Finally, though parks are not organizations, they are public resources, and there is evidence that black and Latinx neighborhoods have less access to public parks, and public funding exacerbates this inequality (Wolch, Wilson, and Fehrenbach 2005). Overall, these findings are particularly troubling for low-income populations of color, who are less likely to have access to organizational resources due to both their race and socioeconomic status. Furthermore, given the history of policies and practices that discriminate against populations of color in the United States, these groups are more likely to live in poverty from generation to generation than white populations (Sharkey 2008).

Immigrants are marginalized similarly to communities of color in many respects, but a different organizational pattern emerges for immigrant neighborhoods. Instead of fewer organizational resources, scholars actually find a more positive relationship between the

concentration of immigrants and organizations. For example, immigrant neighborhoods have been found to have more hardware stores, grocery stores, laundry facilities, banks, pharmacies, hospitals, and doctors offices, although they have fewer restaurants, child care centers, and religious

institutions (Freeman Anderson 2017; Small and McDermott 2006). These findings provide support for immigrant enclave theory, which proposes that immigrant entrepreneurship leads immigrant neighborhoods to have more organizations (Aldrich and Waldinger 1990; Portes and Bach 1985; Logan, Zhang, and Alba 2002). Immigrant enclave theory may hold true as it relates to immigrant

entrepreneurship, but immigrant neighborhoods may still face discrimination when it comes to political processes. Immigrant neighborhoods have been found to lack access to nonprofit

organizations, such as immigrant organizations and social service providers (Joassart-Marcelli 2013; Roth and Allard 2016).

Just as organizations are embedded in neighborhoods, they and their neighborhoods are embedded in cities and larger political and economic fields. Public agencies function within larger political contexts and funding environments. Businesses rely on government incentives, must conform to government regulations, and are shaped by large institutional lenders. As such, scholars have found that the overall composition of cities affects the distribution of resources across

neighborhoods. In cities with a history of racial segregation, black neighborhoods have consistently less access to social services than white and Latinx neighborhoods (Allard 2004; 2008). In regards to for-profit organizations, the picture may be more complicated. Metropolitan area segregation is associated with less access to banks, but greater access to grocery stores, for black and Latinx populations (Steil, De la Roca, and Ellen 2015).

Overall, research suggests that the decline of organizations encountered in some urban neighborhoods is more a function of segregation and depopulation rather than concentrated poverty (Massey 1990; Massey and Denton 1993; Small and McDermott 2006). In fact, poor neighborhoods are able to support businesses, and governments appear to target resources to neighborhoods with higher poverty levels. This holds true, however, only so long as the poor neighborhoods are predominantly white. Once race is taken into account, poor communities of color have access to fewer organizational resources, and political and economic processes exacerbate the inequality between white communities and marginalized communities of color. The story is different for immigrant communities, but clarity is lacking in regards to how racial composition interacts with the concentration of immigrants.

Measuring access: Beyond geographic proximity and institutional resources

The location of organizations and distribution of funding across low-income neighborhoods of color is important insomuch as it provides access to resources for marginalized populations, but what does it mean for these populations to be able to access organizational resources? In the above referenced research, scholars address the question of access by looking at geographic proximity to organizations. This generally takes the form of the organizational density of neighborhoods or census tracts. Sometimes it accounts for the potential demand placed on an organization, such as the number of low-income people who live nearby (Allard 2008). Either way, these measures are derived from the fact that people are more likely to engage with organizations that are located within a few miles of their homes (Allard, Tolman, and Rosen 2003). For starters, it takes less time to travel to an organization if it is located nearby, something that is particularly important for those who work multiple jobs, take care of children, or have limited transportation options. Additionally, people are more likely to be aware of organizations and the resources they provide if the

organizations are located within their neighborhood.

Another measure of access focuses on the distribution of public funding and asks whether organizations in marginalized neighborhoods are more likely to receive public resources than those in more socioeconomically advantaged neighborhoods. This measures is valid because individuals and families are having to access the social safety net increasingly through organizations, and public funding is a fundamental determinant of organizational resources (Allard 2008). Moreover, in recent decades, nonprofit organizations have become more reliant on public funding to serve populations in need (S. R. Smith and Lipsky 1995).

In addition to relying on public funding, organizations broker non-monetary resources, such as information, services, and material goods (Small 2009; Small, Jacobs, and Massengill 2008). For example, organizations garner information, such as updates on immigration, schools, and health care

policies and laws, from community partners, and they share that information with community members. They refer individuals to organizations, and they invite outside organizations to provide services on-site. They also receive and distribute non-cash material goods, such as food and museum passes, to members and clients. In studying child care centers in New York City, Mario Small (2009) finds that influence from the state and large nonprofits, more than neighborhood characteristics, determines how many inter-organizational ties organizations form. For government-funded child care centers, in particular, the state and nonprofit funders exert pressures on centers to form ties and broker resources as a condition of funding.

Whether scholars look at the distribution of funding, regulatory guidelines, or funding incentives, the focus remains on how institutions determine the distribution of organizational resources across neighborhoods. In the case of funding, governments and large nonprofits may directly decide where grants and contracts go and what criteria are used to allocate resources. For inter-organizational ties, these same public and private funders are able to exert pressure on grantees to broker certain resources as a condition of funding. A focus on institutional funding and

pressures, however, overshadows how communities themselves shape the distribution of resources. To fully understand how organizations shape opportunity at the neighborhood level, scholars have to look beyond geographic proximity to services, the distribution of public funding, and the influence of institutional pressures. These are all key measures of access, but they are not the only ones that affect how likely low-income populations of color and immigrants are to benefit from organizational resources. As Nicole Marwell and Aaron Gullickson (2013, 325, emphasis added) point out, a focus on where organizations are located is “hampered by the reality that the existence of an NPO in a particular location is an indirect proxy for understanding the availability of service resources in that location.” Geographic location is not the only indirect proxy that can be used.

The ability of organizations to provide meaningful access to resources requires more than a physical presence in the neighborhood and the ability to secure public funding. For example, an organization may be located in a neighborhood, but it does not provide much value to individuals if it is not open outside of work hours, has limited resources, or is unknown to community members. Immigrants who do not speak English may feel more comfortable accessing an organization that employs people who speak their language and have similar ethnic backgrounds, and undocumented immigrants may be more likely to access services if they do not have to disclose personal

information. As Michael Lipksy (1980) illustrates in Street-Level Bureaucracy, how front-line public employees treat individuals affects how likely those individuals are to try to access public benefits.

Access is shaped by social, economic, political, psychological, and physical factors, at a minimum. Location, hours of operation, and staffing levels determine whether one can get to an organization and receive assistance when they do. How friendly employees are and the comfort of the physical environment influences how welcoming an organization is for those who visit. Those who are older adults, have disabilities, or travel with children in strollers rely on buildings being physically accessible. Overall, access requires that individuals know about the organization and the services it offers, are able to travel to the organization while it is open, feel comfortable going into the organization’s building, and feel welcome when they are there. Moreover, once reached, the organization has to be able to provide access to resources of value.

Another important consideration when looking at access is that it may not be extended uniformly to all in a community. Most organizations target resources to specific populations, such as children or members of a religious group; they target them to those who are able and willing to pay for services; or their services are means-tested and reserved for those who can prove they are low-income. Within organizations, resources may be more accessible to some groups than others, even though all are considered target audiences. This can be seen in some public schools where

parents have managed to target resources to higher income, white students at the expense of low-income students of color, even though both populations attend the same school (Cucchiara 2013). It is also apparent in gentrifying communities where longtime residents start to feel politically or socially displaced from community-based organizations to which they belong, despite the fact that they still technically have access to these organizations (Hyra 2017). These are but a couple of examples of how organizational presence alone does not guarantee equal access for all participants. In general, organizations are not monolithic structures with rational, clearly defined interests. Rather, one organization may have multiple interests that are uncoordinated and competing (Meyer and Rowan 1977).

The ability of organizations to broker resources that are public and private, institutional and community-based should be taken into account when looking at how resources are distributed across organizations. For starters, not all organizations that help marginalized populations to get by and get ahead rely primarily on institutional funders. Additionally, private community resources may also shape organizations that rely on institutional funders. Such community resources may come in the form of volunteers and non-monetary donations from community members. For example, a community member may bring in friends, family, and colleagues who then offer resources. Alternatively, an informal community group may look to reach a broader audience by connecting with a formal organization. A range of organizations—from public schools to nonprofits to religious institutions—rely on these types of community resources.

Despite the use of community resources across some types of organizations, there are at least three reasons why scholars may overlook these types of resources in favor of institutional resources. First, data on institutional funding is relatively accessible to researchers, whereas

organizations may not keep track of community resources. Records of public contracts and grants, in particular, are likely available because governments publish them or researchers can request them

through the Freedom of Information Act. Second, institutional funding is easily quantifiable, and focusing on funding allows researchers to measure disparities across organizations. Third, most organizations need more than donations and volunteers to operate. Even those that rely on

community resources need large sources of funding to pay for staff, space, and utilities. Thus, there are undeniable reasons to study institutional funding, but I argue that there are also compelling reasons to look at how communities shape organizational resources and access, even if the resources they provide are more difficult to identify and measure.

In addition to incorporating community resources, I propose that new measures of access be considered. First, outreach on the part of organizational staff helps to ensure that community members are aware of organizations and the services they provide. Second, whether individuals access an organization and the resources it provides will be shaped by how comfortable they feel doing so. Welcoming practices, such as friendly, knowledgeable, and bilingual staff, make individuals feel more comfortable going to an organization and asking questions of staff. Third, practices that make individuals feel more comfortable spending time in an organization and

returning to it increase access over the long-term. Such practices might include signs and materials in multiple languages, coordinated activities for children and adults, and the ability to access

resources anonymously. These measures are not necessarily quantifiable, but practices that increase access along these dimensions have tangible results for marginalized populations.

Why immigrants and public libraries?

If the focus is on organizational resources and access to them by marginalized populations, why look at immigrants and public libraries? One reason is that immigrants occupy an increasingly precarious position in American society, and they are facing more and more barriers to accessing support. Non-naturalized immigrants are over sixty percent more likely to live below the poverty

level than the native-born population.2 Despite this greater need, immigrants living below the poverty level are less likely than those who are poor and native-born to access public supports. Policy changes since the 1990s have cut benefits for immigrants, and recent changes to the “public charge” rule are discouraging immigrants from accessing benefits for which they qualify. In addition, immigrants must generally access any support in-person through local organizations because there is no national infrastructure for immigrant integration. This is becoming increasingly difficult, though, as immigrants face greater risks of being stopped by immigration officials when going out into public places, not to mention traveling to and from these places. Overall, local organizations that provide immigrant services are charged with providing greater supports to immigrants and maintaining access despite growing barriers to reaching immigrants.

Public libraries are not part of the traditional social safety net, but they provide a range of programs and services for immigrants. Since they first proliferated across the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, public libraries have cultivated resources, designed programs, and engaged in community partnerships to serve immigrant populations (Jones Jr. 1999). While the programs and resources have changed somewhat over time, this active engagement with immigrant populations continues to this day and facilitates immigrant integration. It takes the form of citizenship preparation materials and programs, English as a Second Language classes, foreign language collections, bilingual programs, and trainings on how to protect one’s rights when approached by immigration officials (Cuban 2007; Koerber 2018). Some public libraries even provide assistance to small immigrant businesses (Stephens 2015). According to Eric Klinenberg, they provide more English language instruction and citizenship classes than any other public institution (Mars, n.d.).

2 As of 2017, 14.2% of the native-born population, 11.1% of naturalized citizens, and 22.9% of non-naturalized immigrants lived below the poverty level in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau 2017).

What distinguishes public libraries from other organizations that provide similar services is that public libraries do so for free and are open to all. Additionally, the services they provide are not means-tested benefits that are targeted to only those who qualify. Rather, their services and

resources are available to everyone regardless of age, familial status, income, employment status, place of birth, citizenship status, race, ethnicity, religion, or any other ascriptive characteristics. Furthermore, individuals can use library spaces, ask for help, and attend programs anonymously. For those who want library cards, they can often apply for one without having to provide

government-issued identification. This ability to access resources anonymously helps to provide a sense of security for immigrants who may be concerned about identifying themselves and their immigrant status.

Public libraries are also useful sites of inquiry from a theoretical perspective because they are organizations that are responsive to community needs and draw from community resources. There are a few key ways in which public libraries are particularly attuned to the needs of their

communities. First of all, the library profession encourages libraries to provide services that are “user-centered.” The term “implies a sense of agency on the part of the users, with services that meet users at their point of need, in the manner in which they want to be served” (Barniskis 2016, 138). This results in services that adapt to the unique needs of libraries’ communities. Moreover, public librarians actively try to anticipate and meet the evolving needs of their communities, as illustrated by Rachel Scott (2011, 192):

Some people do not recognize that they are paying for library services with their tax dollars and that the library is there to serve them. It is our job as librarians to help the public understand that the library is there for them and that our mission is to meet their needs. To do this effectively, we need to ask people what they need and want from their library and actually listen to what they have to say. Then, we should adjust our services to best meet these needs.

To meet community needs, library staff exercise discretion in regards to the types of programs they offer and the populations they target. Second, public librarians broker resources from their local

communities and through partnerships with community groups and organizations. Third, public libraries serve as community repositories of sorts. Library staff collect information about their communities, share that information with patrons, and inform community organizations about their libraries’ offerings (Anderson 1994; Lankes 2015).

Finally, public libraries are local government agencies, but they also differ from other

government agencies in a few key respects. According to Institute for Museum and Library Services, A public library is established under state enabling laws or regulations to serve a

community, district, or region, and provides at least the following: 1.) an organized collection of printed or other library materials, or a combination thereof; 2.) paid staff; 3.) an established schedule in which services of the staff are available to the public; 4.) the facilities necessary to support such a collection, staff, and schedule, and 5.) is supported in whole or in part with public funds. (American Library Association, n.d.)

Similar to other government entities, they are established by enabling laws or regulations, are funded at least in part with public funds, and are accountable to the public. Like some public agencies, they are primarily funded at the local level. At the same time, public libraries, and especially their

neighborhood branches, share more in common with local private organizations than other government agencies.

First, many people trust the information that comes from public libraries more than that which comes from other government institutions (Horrigan 2016; 2017). This is particularly important for immigrant populations as they become increasingly fearful of government agencies. Second, public libraries are viewed as safe spaces, and librarians even have a history of not

cooperating with law enforcement agencies when they have suspected that cooperation would pose a threat to the civil liberties of patrons (Matz 2008). Third, public libraries are one of the oldest examples of public-private partnerships in the United States. Private citizens helped to fund the country’s first large public library in Boston, and it was through a combination of private capital investment from Andrew Carnegie and public operating funds that public libraries proliferated in the

late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries across the country.3 In the current day, public libraries continue to draw on donations, volunteers, and partnerships with local organizations. This ability to broker community resources and secure private sources of funding has helped to integrate public libraries with their local communities.

Public libraries are bureaucratic public institutions, but they also offer an opportunity to study how communities shape organizational resources independent of institutional forces. Neighborhood branches function as small organizations within larger institutions in that they occupy a physical space within a neighborhood, serve a community of patrons, and are run by a dedicated staff that has the discretion to determine and meet the needs of its community. As Klinenberg points out, “Libraries have reinvented themselves, and one of the things that is so striking about them is that the local staff has the capacity and agency to develop programming that works for the community that they’re in” (Mars, n.d.). Additionally, community members organize around and support their local neighborhood branches, especially when their branches are

threatened. This dynamic is epitomized by Friends of the Library groups, which are comprised of members who donate goods to the library, volunteer their time, do outreach, and coordinate events. Overall, there is a degree of independence within neighborhood branches that allows for the study of how neighborhoods shape organizational resources. Furthermore, by focusing on neighborhood branches within one public library system, it is possible to hold institutional funding and pressures relatively constant and focus on the influence of neighborhoods and communities.

3All Carnegie library grants required that cities and towns commit annual operating funds equal to ten percent of the initial grant. In committing over a million dollars to the establishment of a public library in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Carnegie wrote, “I am clearly of the opinion that it is only by the city maintaining its public libraries as it maintains its public schools that every citizen can be made to feel that he is a joint proprietor of them, and that the public library is for the public as a whole, and not for any portion thereof; and I am equally clear that unless a community is willing to maintain public libraries at the public cost very little good can be obtained from them” (New York Times 1890, 1).

Research questions

This dissertation research builds on the literature that examines how access to organizational resources varies across neighborhoods, but it is distinct from the existing literature along two key dimensions. First, I expand the concept of access beyond geographic proximity and public funding. In this study, the measure of access incorporates 1) geographic proximity, 2) the availability of resources targeted to a population in need, 3) community awareness of the organization and the resources it provides, and 4) an environment that facilitates continued community access. Second, I am interested in not just how resources vary across neighborhoods in regards to demographic composition, but also why we see variations. What aspects of the local neighborhood—such as community needs, willing volunteers, and local organizations—help or hinder public libraries to serve immigrant populations?

With these considerations in mind, I broadly ask: how do neighborhoods shape

organizations’ ability to target resources to populations in need? Or, in more precise terms: how do neighborhood demographics and local organizations structure the ability of Boston Public Library (BPL) branches to provide access to institutional and community resources for immigrant

neighborhoods? I answer these questions through a mixed-method study of immigrant services and programs across the neighborhood branches of the BPL that draws on structured interviews with branch librarians and library professionals, participant observation, organizational documents and archives, and library usage and program data. I find that organizational resources are not always aligned with neighborhood needs, and this is largely a result of a system with limited resources that must draw on community resources. Though reliance on community resources results in a spatial mismatch between needs and services at times, it also produces distinctive and valuable programs that meet the unique needs of immigrant communities and helps local organizational partners to reach immigrant populations.

Dissertation structure

In this chapter, I have introduced some of the key theories and questions that drive this research. Those are questions of how organizations provide access to opportunity and what role neighborhoods play in shaping that access. In doing so, I focus on the role that public libraries play in providing services to immigrant populations and how they garner community resources to do so. Chapter two offers a more thorough engagement with the literature on immigrant integration and the role of organizations, especially public libraries. It also addresses the barriers immigrants face accessing the social safety net and public library services. Chapter three begins with an overview of Boston’s immigrant population and a brief history of the BPL and how it has engaged immigrants since its founding. The second part of the chapter details the research design and methodology of this study. Chapter four focuses on how neighborhood branches of the BPL provide services and programs that reach immigrants and facilitate immigrant integration. Additionally, it examines how public library programs and services are distributed geographically in relation neighborhood

demographic characteristics. Chapter five engages in a discussion of how neighborhood factors influence the distribution of programs and services across neighborhood branches. Specifically, it highlights how expressed community needs, level of volunteerism, cultural sharing practices, and organizational partnerships shape organizational resources. Finally, chapter six concludes with a discussion of the findings and how they contribute to theory, policy, and practice related to immigrants and access to organizational resources.

Chapter two | Literature review: Immigrants, access to opportunity, and

public libraries

Introduction

Immigrants are more likely to live in poverty than the native-born population in the United States, and this disparity is driven primarily by the higher poverty rates of non-naturalized

immigrants, who account for over half of immigrants. In 2017, twenty-three percent of non-naturalized immigrants lived below the poverty line, compared to seventeen percent of the native-born population and eleven percent of naturalized immigrants (U.S. Census Bureau 2017). Following a similar trend, the unemployment rate of non-naturalized immigrants was 4.5 percent, compared to 4.1 percent for the native-born population and 3.8 percent for naturalized immigrants (U.S. Census Bureau 2017). Despite the fact that there is a greater degree of need among the non-naturalized immigrant population, those who are low-income are less likely to take advantage of public benefits than the low-income, native-born population due to eligibility restrictions and fear of being denied citizenship as a result of accessing benefits. Given the socioeconomic needs of

immigrants, along with the other cultural and political barriers they face, how do immigrants get by and get ahead in the United States?

This chapter begins with an overview of immigrant integration and how the government and private organizations structure the integration process in the United States. It then looks at the immigrant social safety net, how immigrants use it, and the barriers they face accessing it.

Understanding how immigrants access welfare programs is informative insomuch as it identifies the extent to which immigrants’ economic needs are being met. Furthermore, understanding the

barriers that immigrants face accessing public benefits can shed light on the barriers they are likely to face when accessing other services through government agencies and private organizations. Finally,

this chapter ends with a review of how public libraries, in particular, facilitate immigrant integration and what barriers prevent immigrants from taking full advantage of these services and programs.

Immigrant integration

Immigrant integration is a two-way process of inclusion that involves mutual adaptation by immigrants and host communities, and the process stands the best chance of success when both immigrants and host communities design it. Through this process, immigrants become more like their host communities, and host communities come to resemble their immigrant members. More than just acculturation, integration is about improving the overall well-being of immigrants over time and across generations. In the United States, the lack of a national immigrant integration policy forces integration to take place almost entirely at the local level (Bloemraad and de Graauw 2011; Mollenkopf and Pastor 2016).

Integration encompasses socioeconomic measures of opportunity that apply to all populations, regardless of place of birth, along with measures that are specific to the needs of immigrant populations. Five key indicators of immigrant integration include: 1) language

proficiency, 2) socioeconomic attainment, 3) political participation, which includes legal status and citizenship, 4) residential integration, and 5) social interaction with host communities (Jiménez 2011). These indicators of integration are by no means mutually exclusive. For example, English proficiency is an indicator in and of itself, but it also contributes to other measures of integration, such as socioeconomic attainment and social interaction. It is for these reasons that Tomás Jiménez (2011, 11) describes English proficiency as “a virtual requirement for full participation in US

society.”

English language proficiency aids all dimensions of integration. It helps immigrants access better jobs, participate in the political system, and make social connections. Immigrants from

non-English speaking countries who speak non-English earn ten-to-fourteen percent more than those who are not proficient, and unemployment rates are higher among non-English speaking immigrants (Chiswick and Miller 2002; 2015; Soricone et al. 2011). Even as cities incorporate multilingual services, limited English proficiency prevents some immigrants from interacting with public officials and achieving political and socioeconomic integration (de Graauw 2008). English proficiency also helps immigrants to feel a greater sense of belonging and avoid social isolation (Jiménez 2011). Part of the benefit of English proficiency is psychological because it helps immigrants to feel more

confident engaging with others, which facilitates integration along other dimensions (Koerber 2018). Finally, there are transitive benefits of speaking English, too, because the proficiency of one

individual increases the proficiency of other household members.

Among the five indicators, socioeconomic attainment is arguably the most important. As with the native-born population, socioeconomic attainment is achieved through education, well-paying jobs, and access to higher status occupations. It also takes into account measures of wealth, such as homeownership. This indicator of integration is generally measured across generations and in comparison to how the white native-born population fares. Thus, the second generation of an immigrant population may fare better than the first generation along socioeconomic measures, but they are not considered to have attained full socioeconomic integration unless they have achieved socioeconomic parity with the white, native-born population.

Political participation covers citizenship and legal status, voter registration, voting, holding office, and participation in civic life. Like English proficiency, gaining citizenship and legal status assists with other aspects of integration. As described earlier, immigrants who are naturalized face significantly fewer socioeconomic hardships than those who are non-naturalized, and both groups fare better than those who are undocumented. More so than other indicators of immigrant

more or less difficult to become naturalized, either by making the procedures and eligibility requirements for naturalization more or less restrictive or by changing the benefits for which naturalized and non-naturalized immigrants qualify. For example, naturalization rates rose when public benefits were cut back for non-naturalized immigrants under welfare reform in the 1990s, and naturalization applications have risen again in recent years under the Trump administration’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies because anti-immigrants now stand to gain more from citizenship (Blizzard and Batalova 2019).

In general, residential integration occurs when immigrants’ living patterns become less segregated over time. Just as socioeconomic status influences the living patterns of native-born populations in the United States, it also shapes residential integration for immigrants. When immigrants first move to the United States, they often live in segregated, low-income ethnic enclaves. This is due to socioeconomic necessity and because these areas provide greater social supports. With socioeconomic attainment, immigrants are able to choose among a wider range of areas, and they tend to move to places that have lower concentrations of immigrants. Exceptions occur among some ethnic groups that choose to continue living in ethnic communities, even as their socioeconomic status rises, but most immigrants and their decedents move into less segregated areas over time (Logan, Zhang, and Alba 2002).

Finally, social integration includes intermarriage across ethnic groups and nationalities and perceptions of belonging. English language proficiency and citizenship both contribute to

perceptions of belonging, but the measure is amorphous and constantly evolving based on how people view what it means to be “American.” For example, while three quarters of Americans believe that immigrants should be required to learn English as a condition of citizenship, a growing portion report that they are not bothered by the limited English proficiency of individuals they encounter (Page 2013; Pew Research Center 2018).

Social inclusion is also a part of social integration. For immigrants who work or are students, sites of employment and schools can facilitate social interactions. Many immigrants, however, do not necessarily work in the traditional sense or attend school, and they may find themselves socially isolated (Banulescu-Bogdan 2020). These vulnerable immigrant groups include stay-at-home spouses, parents of young children, older adults, and those who are unemployed. For these populations, volunteer opportunities and community-based programs can help to build social ties among immigrants and with native-born individuals (Banulescu-Bogdan 2020; Handy and Greenspan 2009).

Immigrant integration and the public sector

In the United States, the federal government controls borders and immigration, but it plays a limited role in regards to immigrant integration. Instead, integration measures are largely devolved to the local level, and municipalities are left with the decision of what services to provide to immigrants and how. As John Mollenkopf and Manuel Pastor (2016, 2) write, “[W]hile the federal government has the formal responsibility for determining how many immigrants come into the country and for preventing those who lack permission from entering, it falls to local and regional jurisdictions to frame the living experience of immigrants.” Since 2000, there has been a surge in pro- and anti-immigrant laws passed at the state and local levels (Steil and Vasi 2014), and these contribute to geographic diversity in regards to the “warmth of welcome” municipalities extend to immigrants (Mollenkopf and Pastor 2016). Just as residential contexts influence socioeconomic outcomes for the general population (Sharkey and Faber 2014), so too does place determine access to opportunity for immigrants.

State and local policies contribute to the uneven “warmth of welcome” that places extend to immigrants both across and within places. One of the most notable examples is the willing

participation of seventy-eight city, county, and state law enforcement agencies with the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) 287(g) program, which deputizes state and local law enforcement agencies to carry out federal immigration enforcement. This is in contrast to the approximately one hundred and forty sanctuary cities, counties, and states that have enacted policies refusing to fully honor ICE detainers (Delgado 2018). These sanctuary jurisdictions may have local and state policies that are welcoming to immigrants, but they also have become targets of federal ICE raids under the Trump administration (Dickerson, Kanno-Youngs, and Correal 2020; Jordan 2017).

Another way that some cities have established more welcoming policies is through the establishment of immigrant affairs offices (de Graauw 2015; 2018). These types of offices welcome immigrants, strive to create opportunities for inclusion, build public awareness of the economic benefits that immigrants provide for cities, and facilitate interactions between immigrants and the native-born population. In recent years, these types of offices proliferated across cities, and not just cities that are politically liberal. As of 2016, forty-one cities had immigrant affairs offices, and in only fifty-nine percent of these cities were the majority of voters Democrats (de Graauw and Bloemraad 2017). Thus, different local factors are at play beyond political orientation that influence how welcoming localities are of immigrants.

Even within the same places, state and federal laws differently influence how responsive bureaucrats are to the needs of immigrants. For example, in the case of educational agencies, federal law requires elementary schools to serve all children, regardless of immigration or legal status; meanwhile, public universities may operate under restrictive state laws that prohibit them from enrolling undocumented immigrants (Marrow 2009). Even in places governed by restrictive laws and elected officials who promote anti-immigrant policies, professional and organizational factors lead some public agencies to be more responsive to the needs of immigrants. Federal, state, and