Digitized

by

the

Internet

Archive

in

2011

with

funding

from

Boston

Library

Consortium

IVIember

Libraries

'31

Dewey

[415 ;

DM

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Worl<ing

Paper

Series

Copycat

Funds:

Information Disclosure Regulation

and

the

Returns

to

Active

Management

in

the

Mutual

Fund

Industry

Mary

Margaret

Myers

James

M.

Poterba

Douglas

A.

Shackelford

John

B.

Shoven

Working

Paper

C2-04

October

2001

Room

E52-251

50

Memorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without

charge from

the

Social

Science

Research Network Paper

Collection

atf

Massachusetts

Institute

of

Technology

Department

of

Economics

Working Paper

Series

Copycat

Funds: Information Disclosure

Regulation

and

the

Returns

to

Active

Management

In

the

Mutual

Fund

Industry

Mary

Margaret

Myers

James

M.

Poterba

Douglas

A.

Shackelford

John

B.

Shoven

Working

Paper

02-04

October

2001

Room

E52-251

50

Mennorial

Drive

Cambridge,

MA

021

42

This

paper

can be

downloaded

without

charge

from

the

Social

Science

Research

Network

Paper

Collection

atMASSACHUSEHS

INSTITUTEOF

TECHWOLOGY

MAR

7

2002

LIBRARIES

Copycat

Funds:

Information

Disclosure

Regulation

and

the

Returns

to

Active

Management

in

the

Mutual

Fund

Industry

Mary

MargaretMyers

Graduate School of Business, University

of

Chicago

1101 East 58th Street,

Chicago

IL60637

James

M.

PoterbaDepartment of Economics,

MIT

50

Memorial

Drive,Cambridge

MA

02142-1347

Douglas

A. ShackelfordKenan-Flagler Business School, Universityof

North

CarolinaCampus

Box

3490,McCoU

Building,Chapel

Hill,NC

27599-3490

John

B.Shoven

Department of Economics,

Stanford University EncinaHall, StanfordCA

94305

Revised October

2001

Contact Author:

James

Poterba,Department of

Economics

E52-350,MIT,

50

Memorial

Drive,Cambridge

MA

02142-1347;tel (617)

253

6673;fax (617)258

7804; emailpoterba@mit.edu

ABSTRACT

Mutual

ftindsmust

disclosetheirportfolio holdingstoinvestorssemiannually.The

costsand

benefitsof suchdisclosures are along-standingsubjectofdebate.For

activelymanaged

funds, onecost ofdisclosureisapotentialreductioninthe private benefits firomresearch

on

asset values. Disclosureprovidespublic accesstoinformationon

the assets thatthefundmanager

views

asundervalued. Thispapertries toquantifythispotentialcostofdisclosure

by

testingwhether

"copycat"mutual fijnds, fiands thatpurchasethe

same

assetsasactively-managedfiindsassoonasthoseassetholdingsare disclosed,can earnretums that aresimilartothose oftheactively-managedfiands.Copycat

fiandsdo

not incur the researchexpensesassociatedwiththeactively-managed fundsthattheyaremimicking,butthey

miss

the opportunitytoinvestinassets that

managers

identify as positivereturn opportunitiesbetween

disclosuredates. Oiorresultsfora limited

sample

of

highexpensefiands inthe 1990s suggestthatwhileretums

beforeexpensesaresignificantlyhigherfortheunderlyingactively

managed

fundsrelativetothecopycatfunds,after expenses copycat fundscam

statisticallyindistinguishable,and

possiblyhigher, retums thantheunderlyingactively

managed

fiands.These

findings contributeto thepolicydebateon

theoptimalleveland

frequency of fimddisclosure.We

aregrateful toDan

Bergstresser, Joel Dickson,JenniferWilson, seminarparticipants atthe UniversityofIllinois-Chicago

and

IndianaUniversity,and

especiallyMark

Wolfson

for helpfiildiscussions.We

alsothankJennifer Blouin, V.J. Bustos,Rachel Ferguson, Michael Myers,Angel Townsend,

andCandice

Whitehurstforexcellentresearchassistance,theErnst

&

Young

Foundation,theNationalScience Foundation(Poterba)and

theUniversityofChicago

(Myers)forresearch support,and John

RekenthalerThe

U.S. Securitiesand

Exchange

Commission

is ciirrentlyconsideringmodifying

theregulationsthatgoverndisclosuresthat

mutual

fundsmust

make

to theirshareholders.Under

the1940

InvestmentCompany

Act, investmentcompanies

must

disclose boththeirperformance

and

theircurrent portfolioholdingsinsemi-annualreportstoshareholders.

These

reportsmust be

senttothe shareholdersno

more

thansixty daysafterthereportingperiodends.

A

number

oforganizationsrepresentingfiand shareholdershave

calledformore

frequent disclosureof

mutual fundholdings,on

thegroundsthattheywould

enableinvestors to

more

accuratelyselect ftindsthatmatch

theirinvestmentobjectives.More

frequentdisclosure

would presumably

permit shareholderstodetect,sooner,changes

infund investmentstrategy.They would

consequently reducetheriskthatfundmanagers

couldpursue investmentstrategies thatdo

not coincide withtheirshareholders'wishes.

Previousresearch

on

financialdisclosurerecognizesthatmandatory

disclosurehas bothcostsand

benefits.

The

costsinclude thedirectexpensesassociatedwithproducingand

disseminating informationon

investmentpositions,aswell as arangeof

potential coststhata disclosermay

facewhen

privateinformation

becomes

publiclyavailable.The

benefits ofdisclosureemanate

from improved

monitoringof flmd managers,

and

from

potentialimprovements

in investorchoicethat resultfrom

detailedinformation availability.

Both

the costsand

benefitsof

disclosure are typicallyverydifficulttoquantify.In themutual fundcontext,

Wermers

(2001) notesthatthere aretwo

potentialcoststotheinvestors inafiind

when

thefundisrequired to disclose itsholdings.First,when

afiind disclosesitsholdings, it

becomes

easier forother investorstouse informationon

fiind inflowsto "front-run"thefiind'strades,therebybidding

up

the pricesof

the securities thatthefundmanager

wishestobuy. Thiscostispresumably

greaterwhen

disclosureismore

frequent,and

ittranslates intoalowerreturnon

the fimd's investments. Second,disclosurereducesthetime period overwhich

fundinvestors areabletoreap theprivaterewards oftheirmanager'ssecuritiesresearch.

The

managers

who

directinvestmentsinactively-managed

open-end mutualfiindscarryoutresearchaboutvarious securities toidentify underpricedassetsthat will generateabove-average, risk-adjustedreturns.

Because

disclosure reveals the identityofthePotentialcompetitors, as well as

fund

shareholders, learnaboutafund manager's investmentswhen

thefiinddiscloses itsholdings.

The

fund manager's uniquereturntoinvestinginthesecuritiesthat hisresearchsuggestsareunder-valued istherefore limitedtothetime

between

thecompletion ofthe research,and

thenextdisclosuredate. This analysispresumes

thatresearchby

fundmanagers

uncoverspositivereturn opportunities;a largeempirical literature,reviewedfor

example

inGruber

(1996),suggeststhatthisassumptionis

open

todebate.These

two

costsmust be

balancedagainst thepotentialbenefits ofdisclosurebothfrom

thestandpoint

of

anindividual ftindmanager

who

is considering increasing thefrequencyofdisclosure,and

fi-omthestandpoint

of

aregulator tryingtodesign an optimalpolicy.One

potential benefitof

disclosuremay

be heighteneddemand

forthe securitiesowned

by

adisclosingfijnd. Ifother investorsdecidetopurchasethe securities thatafimd already

owns

because theybelieve thatthe disclosingmanager

hasprivate information, this

may

driveup

thepriceof

these securities,therebyraising the returnson

thefiindthat

makes

the disclosure.Another

benefit isthatsome

investorsmay

attachsubstantialvalue tofrequent disclosure,and

therefore

be

preparedtoaccepthigherfeesorlowerreturnstoreceive frequentfunddisclosures. Frequentdisclosure

makes

itdifficultforftindstopursuestrategies thatare substantiallydifferentfrom

theones thattheyadvertise.The

gainsfrom

suchdisclosuredepend on

the likelihoodthat ftindschange

theirstrategieswithout informingtheirshareholders, and

on

the costtoshareholdersofdeviationsfrom

pre-announced

strategies.Although

the current regulatoryenvironment

requiressemi-annualdisclosure,some

managers

voluntarilydisclosetheir fiindpositionsmore

frequentlythantheSEC

requires.They

presumably

believethatinvestorsaremore

likely to invest ina fimdthatprovidestimely portfolioinformation,

and

theyvaluethe associated increasein theirfiind'sassetsmore

highlythan the potentialfutureinflowsassociatedwithhighercurrentreturns.

The

possibility thatsome

firmsmay

voluntarilydisclosemore

than the regulatorsrequire, toattractaparticular investorclienteleisnotuniquetothemutual fimd market. In discussing insider trading

firm'sshares,

some

firmswould

voluntarilychoosetoprohibitsuchtransactions, theywould

therebyattractinvestors

who

were

preparedtoacceptslow

incorporationof

informationintoprices (ifinsiderscould nottrade) inreturn forexcludingbetter-informed traders

from

themarket.A

thirdpotential benefitof

disclosureisthatitmay

convey

informationon

a firm's successfiilpastinvestmentsto prospective investors

and

therebyattractthem

tothefiind.Verrecchia (1983)notesthatvoluntarydisclosures

of

product innovations or otherresearchresultsmay

increasefirm valueby

persuading investors

of

thefirm'sresearchacumen.

Thiscan occureven though

disclosurefacilitates thecompetitivestrategies

of

rivalsand

reducesthemarket

valueof

the proprietary returnson

theresearchbeingdisclosed.

The

literatureon

"window

dressing"by

mutual fundsand

otherinvestmentmanagers,including Carhart, Kaniel,

Musto,

and Kadlec

(2000), Lakonishok,Shleifer, Thaler,and Vishny

(1991),and O'Neal

(2001), suggeststhatmanagers

believethatinvestors willjudge

prospectiveperformance

on

thebasis

of

pastperformance.The

problem of

decidinghow

toregulateinformationflowsbetween

amutual

fiindand

itscurrentand

prospective investorsisclosely relatedtoarangeof problems

in financialaccountingregulation.For

example,regulators

and

managers have

long debatedthe extenttowhich

requiringgeographicsegment

disclosures,

and

othertypesof

detailed financialinformationrelease,conveys

valuable informationtoafirm'scompetitors withoutproviding

much

informationtoinvestors.A

number

of

previousstudieshave

consideredthedesign

of

disclosure regulation forfinancialinformation. Foster(1980) notes thatthe"extemalities" associatedwithfinancial reporting

may

leadfirmstounder-provide informationinanunregulated market.

Admati and

Pfleiderer(2000) investigatethenatureof

voluntarydisclosureequilibria, andthecircumstancesunder

which

disclosureregulationiswelfare-enhancing.Both of

thesestudiesnotethatthe optimalregulatory structure for disclosurewill

depend

on

the firm-specific costs ofdisclosinginformation.

Optimal disclosure policy

depends

on

the costsand

benefitsofdisclosure,yet thereisremarkablylittle empiricalevidence

on

eitherofthese issues. This paper seekstoprovidenew

insighton one

ofthereductionin potentialexcessreturnsearned

by

themanagers of

actively-managedequity funds.We

emphasize

that thisisonlyone of

thepotentialcostsofdisclosure,and

that animproved measure of

thiscostalonedoes notresolve thequestion

of

theoptimaldegreeof

disclosure,which

must depend on

thecosts aswell asbenefits

of

potential disclosurerules.To

investigatehow

disclosure affectsthe returnsearnedby

actively-managedmutual fiindsandother investors,

we

create"copycat"fiindsthatallocate assetstomatch

thelatestpublicly-disclosedholdings

of

actively-managed funds.We

thencompare

the returnsof each copycatfiindwiththe returnsof

themutual

fundthatitmimics. Ifresearchisvaluable inuncoveringpositivereturn opportunities, thecopycatfund should earn lowerreturnsthanitsprimitiveactively-managedfiind.

The

activemanager

canimplement

theresultsof

new

researchimmediately,whilethe copycatmanager

can onlytradeon

new

informationafteritispublicly disclosed.

The

copycatfiind'spotentialdisadvantage intimelyaccesstoresearch findings

may

be

offset,however,

by

the fact thatthe copycatfundalsohasvirtuallyno

researchexpenses. Thus,itispossible thatacopycat fiind

and

an activelymanaged

fiondcoulddeliver similar netof expense

returns,even

ifthe copycatfundearns alowerreturn before expenses.We

recognize thatourtestsare ofgreatestinterestwhen

researchby

activemanagers

hasthepotential togenerate positive returns beforefund expenses. Ifactive

managers

areunabletoadd

value throughtheirresearch, copycatfiindsshould beabletomatch

the returnsoftheirprimitivefundsbeforeexpenses,

and

theyshouldoffersuperior returns netof

expenses.Our

research strivestoprovideinsighton

theextenttowhich

expense savings cancompensate

forforegone assetallocation opportunities

on

the partof copycatfunds.We

investigatetheviabilityofthecopycat strategy

by

studyingthe returnstoasetof

actively-managedfiindsandassociatedcopycat fundsfrom

1992-1999.The

view

thatdisclosurerestrictsthecapacityof

actively-managedfiindstoreapthepotential benefits oftheirresearch findings

would

beconsistentwiththenet-of-expensereturnstocopycatfiindsprovingindistinguishable

from

the returnsofprimitive fiinds,whilethebefore-expenseretums ofOur

analysis isdividedinto five sections. Sectionone

summarizes

the disclosure regulationsthatcurrentlyapplytomutual funds

and

providesbackground

forunderstandingour copycat fundstrategy.Section

two

describesour algorithmformanaging

acopycatfluid, including thefrequencyof

portfolioadjustments

and

the relationship betw^een the dateswhen

actively-managedfiindsdisclose informationand

the dateswhen

copycat funds rebalancetheirholdings. Sectionthree explains the selectionprocessfor the actively

managed

fiinds inourdatasample

and

presentssummary

statisticson

theexpensesand

returns

on

these funds. Section four reportsourprincipal empiricalfindings. Inmost

cases,we

findthatreturns tothe primitivefunds

exceed

thoseofthecopycat funds beforeexpenses.When we

compute

returns toboththe primitive

and

thecopycat fundsnetof

expenses,however,returnson

thecopycat fimdsoften

exceed

thoseon

theprimitivefiinds, althoughwe

typicallycannotrejectthe nullhypothesisthatreturns

on

thecopycatfiindsareequaltothoseofthe primitive funds.A

briefconclusionoutlinesseveralbroad

issues relatedtoinformation disclosureby

financial intermediariesthatemerge

firomouranalysis.1. DisclosureRegulations

and

theMutual

Fund

IndustryMutual

fundsarerequiredtodisclosesemiannuallytheirbalancesheets, including alistof

thesecurities thattheyholdandthevalue

of

thesesecurities. Section 30(e)oftheInvestmentCompany

Act

of

1940

stipulatesthe relevant disclosurerequirements,and

specifiesthatthelistofsecuritiesheldmust

be

fora "reasonablycurrent date." Securitiesand

Exchange

Commission

Rule

30bl-l ismore

specificinoutlining theprocessofdisclosure. Registeredinvestment

companies

must

fileform

N-SAR

notmore

than

60

calendardaysafterthe closeoftheirfiscalyear,and

again afterthecloseofthesecond

quarteroftheir fiscalyear.

Fund

familiesvaryin theirdisclosurepolicies.Some,

suchasfiinds in the Fidelity family,do

notmake

voluntarydisclosures.Most

fiinds,however,disclosetheirholdingsbeforetheend

ofthetwo-month

graceperiod, andmany

fiindsdisclose portfolioholdingson

a quarterlybasis.For

example,theVanguard

Group

disclosesitsfunds' holdingseveryquarterwithaone-month

lag. Inaddition,monthly

reportsthat

30

percentof mutual funds,includingtheJanusand

USAA

InvestmentManagement

fiindfamilies,releasecompleteportfolioholdings

monthly

toMomingstar,

a firm that tracks returnsand

providesinvestorswith informationthatthey

may

findusefiilinevaluatingmutual

funds.The

factthatinvestors

pay

substantialsums

toMomingstar

toobtain these datasuggeststhat at leastsome

market

participantsregardfunddisclosuresasvaluableinformation, perhapsbecauseit offersaguidetothe

fiiturebehaviorof fimd managers.

Some

firmseven

disclosemore

fi-equentlythanmonthly.Laderman

(1999)reportsthat the

Open Fund

postsallof

itstradesand

reportsitsentireportfolioinrealtimeon

itsweb

site.Fund

familiesthatdo

not voluntarily disclosetheirholdingstypicallycitedistributioncostsasthemajor

impediment

tomore

frequent disclosures.For

instance,theOmni

hivestmentFund

historicallymailed

monthly

statementsof

fund holdings toitssmallgroup

ofshareholders. Fairley(1997)reportsthatafter

Berger

Associatesfiind familyacquiredOmni,

disclosureswere

reducedtosemiannualreportsbecause

of

distributioncosts.However, even

when

ftindsdo

notmaildetailed disclosurestoall investors,some

ftindswillprovideacompletelistof

theirinvestments, or apartial listingwiththeirmost

significantholdings, to investors. Investors also

may

obtaininformationthatisnotmailedtoall shareholdersby

contacting theftmd

manager

directly.Fund

web

sitesincreasinglydisseminate additional portfolioinformation.

2. Primitive

and

Copycat

Funds

To

evaluateone

ofthe costsof

informationdisclosureforactively-managedequityfiinds,we

design "copycatfiands" that spend nothing

on

researchbutselectassetsby

followingan actively-managedfiind.

The

fiind that carriesout researchon

asset selection istheprimitivefund. Letthe returnon

thisfundequalRprimitive, preexpense,

sud

Ictthcftind'sexpenses equal eper period.The

net-of-expensepretaxretum

toan investorinthisfundisWhen

detailedinformationon

the primitivefund'sportfolioholdingsbecome

available, thecopycatfiind will alignitsportfolioexactlywith thereportedholdings oftheprimitive fiand. Consistent

withthe

SEC

mandatory

disclosurerules,theprimitive flmdisassumed

todiscloseexactlysixtydaysafterthe close

of

the primitive fimd'ssecond and

fourth quartersofthefiscal year. Thisassumptionimplies thatthecopycatfundis alwaysatleast

two months

"outofdate"intracking the primitive fimd. Itcan

be

asmuch

aseightmonths

behindtheprimitive fimd, inthedaysimmediatelyprior toanew

semiannualdisclosure.

The manager

of

the actively-managedfiindchanges assetallocationbetween

the datesofrequireddisclosure,whilethecopycatfiindonlyadjustsitsportfolio

when

themanager

oftheactively-managedfiinddiscloses

new

holdings. Ifidentificationof

new

stocksby

actively-managed fimdsgenerates auniform

distributionof

tradesbetween

disclosure dates,themanager

oftheprimitivefundwill holdasecurityfor fivemonths,

on

average,beforethe copycat fundwillpurchaseit. Thislagmay

be longerifthe active

manager

pursuesstrategies designedtopreventimitation, suchasdelayingthepurchase(sale)of

some

securities thatmay

have

positive (negative) returnpossibilitiesuntiljust afterthedisclosuredate.Ifthe active

manager

iscompletelysuccessful incamouflaging hisorherfund'stme

portfolioholdings,thenthecopycat fundwillnot

even

be

abletoholda laggedversionoftheactively-managedfund'sportfolio. Inthiscase,thecopycatfundwillbe holdinga portfoliothat correspondsto

whatever

assetstheactively

managed

fundfound

itattractivetopurchaseas partofthecamouflage

program.The

extenttowhich managers

atactivelymanaged

fundstradetodisguisetheirholdingsatthetime

of

disclosure isanopen

issue.While

masking

strategiescan avoid informing competitorsand

investorsaboutcurrent portfolio positions,they

may

alsoimpose

potentially substantialtransaction costson

thefund pursuing them.Musto

(1999)discussesmore

generallythepotential gainsfrom

short-termtradingthatisdesignedto affecttheinformationtransmittedto investors,

and

O'Neal (2000)presentssome

evidence offiindreturnabnormalities aroundfund disclosuredates,suggestingthatsome

unusualWe

denotethebefore-expensereturnon

thecopycatfundasRcopycat.preexpense- Ifthestockselectionassociatedwithactive

management

generates positiveretums,we

would

expectthat\^) -^Vropycat,pre-expense -^^primitive,

pre-expense-The

copycat fundisalwaysrelyingon

dated informationinmaking

portfolio choices, soitsretums shouldbe lower

thanthose ofthe activelymanaged

fimdthattakesfull advantage ofnew

informationasitarrives.

However,

thecriticalquestionforinvestorsiswhether

thecopycat fund'sreturn, netof

expenses,exceedsthe

comparable

returnon

the primitivefiind. IfafractionX

of

theactively-managedfund'sexpensesisassociatedwith research

and

other costsofactivemanagement,

suchasbrokeragefees, thenthecopycat fundcangenerateanafter-expense returnof

\^) -^Vropycat, net ^M:opycat, pre-expense "

vA'^^J^-The

parameterX

islikely tovaryacrossfiindsof

differenttypes.Our

analysisfocuseson

pretaxretums,but

we

notethatfortaxable investors, thecapital gains taxliability associatedwith investmentsincopycatfunds

might

be lowerthan those for primitive funds, since thecopycatfiinds willpresumably

tradelessthanthe primitive fund.

Because

the copycatfund onlytradestwiceeachyear,torealignitsportfolioand

that

of

theprimitive fiond,itissomewhat

lesslikelythan the primitive ftindtorealize capital gains.Our

empiricalwork

computes

thedifferentialreturnofthe primitiveand

copycatfiindson

apre-expense

and

apost-expensebasis,and

testsforstatisticallysignificantvaluesof

\

V

^pre-expense ^S^r'nii^i^^'pre-expense ~-^Nropycal,pre-expenseand

\p} ^net l^primitive, net~ ^N:opycat,net •

To

compute

Rprimitive,net,wc

uscthemonthly

return asreportedby Momingstar.

Thisisthechange

inthe fund's net assetvalue(NAV)

duringthemonth

dividedby

the net assetvalueatthe beginningofthemonth, assuming

reinvestmentof

dividendsand

capital gains distributions.NAV

equals the fiind's totalassets, lessfees

and

expenses,dividedby

thenumber

ofsharesoutstanding. Thisreturnisnetof expenses paidfrom

fundassets,suchas 12b-1and

management

and

administrative fees.Our

primitivefundreturnisnotreducedfor loads,brokeragecosts,and

other coststhatdo

noteasilyconvertto

monthly

returns.To

theextentthatactively-managedprimitivefundsareburdened

more

than passivecopycats withthese additionalcosts, Rprimitive,netunderstates the potential net return

advantagesof copycatftmds. In theempiricaltests, Rprimitive, pre-expenseequalsRprimitive,netplusanestimate

of

the

monthly

expenses paidfirom tundassets.The

estimatedmonthly

expenseis 1/12ofthepercentageof

thefund'sassetsdeductedeachfiscalyearforfund expenses.

For

example,assume

thatMomingstar

reportsareturn

of

2.0percent for afund ina givenmonth, and

thatthe fund'sannualexpense

ratiois 1.2percent. In thiscase,theestimated

monthly

expenseratiois0.1 percent, 1.2percent/12,and

theadjustedmonthly

returnis2.1 percent (2.0+

0.1).We

compute

thecopycat'spre-expensereturn, Rcopycat,prc-expense,as thesum

ofthevalue-weightedmonthly

returns foreach stockheldby

the primitivefiind. Portfolioholdingsand

theirweightsarecollected

from Momingstar.

The

monthly

returnsforstocks arecomputed by

compounding

dailyreturnsinthe daily

CRSP

files. Ifthestockislistedon

CRSP,

we

useitsdailyretums

includingdistributions. Ifa

common

stock isnotlistedon

CRSP,

forexample

ifitisa closely-held or foreign-controlledcompany,

we

assume

itsdaily returnequalsthe distribution-inclusive returnon

thevalue-weightedmarket

portfolioas reportedinthe

CRSP

files. Ifacommon

stockheldby

thecopycatfimd dropsfi-omCRSP

duringthesix-month

buy

and

hold periodbetween

information disclosureswe

assume

thattheassetspreviouslyheldinthatstockearn the value-weighted

market

returnuntilthenextdisclosureof informationfrom

theprimitive fund. Thisistantamountto

assuming

thatthecopycatfund

manager

reinvests, inabroadmarket

index, theproceedsfiromsellingsharesthatstoptrading.Many

of

theprimitivefiinds inoursample

holdsome

of

theirassets in securities otherthancorporate stocksthatare included

on

theCRSP

tape.Computing

theretumson

theseotherassetsisproblematicbecause

we

oftenlack detailed informationon

theidentityof

theasset, the returnon

theasset,or both.

To

overcome

theseproblems,we make

a rangeof

assumptions withrespecttocopycatfimdretums. First,

we

assume

thatbonds

eam

theIbbotson Associatesmonthly

returnon

long-termcorporatebonds. Second,

we

assume

thatcashearns theTreasurybillmonthly

rate. Third,we

assume

thatthereturns

on

small equityand

otherassetholdingsare proportionaltothe returnon

the fund's otherassets.Momingstar

roundsthe portfoliopercentage weighttozeroifthefund holdslessthan 0.006 percentof

itsportfolioinaspecific security.

Only

aboutone percent ofthe equitiesheldby

fundsinoursample

haveweights

below

thisthreshold,and

themedian

fundinbothsampleshad

no

holdingsbelow

thisthreshold.'

We

assume

thattheassets in thisunreported categoryareinvestedintheodierassets inthecopycat fund(i.e.,equities,

bonds and

cash),withweightsequal to the shareof

theotherassets inthecopycat fiind'sportfolio. Finally,

we

assume

thatpreferredstockthatisnotlistedon

theCRSP

filesalsoearns theaverage

retum

of

thecopycatfund'sotherassets.We

do

thisbecausepreferred stockhas bothequityand

bond

features.To

illustrateourprocedureforconstructingcopycatfundreturns,suppose afiind'sassetsareinvested

40

percentinCommon

StockA,

which

isincludedintheCRSP

files,25 percentinCommon

Stock B,

which

isnotlistedinCRSP,

30

percentinBond

C,and

4.98percentincash.The

remaining0.02percentofthe portfolioisinvested infour stocks,eachcomprising 0.005 percentoftheportfolio.

First,

we

dropthefourstocksthatcomprise only 0.005 percentof

the fund,becauseMomingstar

reportstheirportfolioweightsas percent,

and

reweighttheremaininginvestments. StockA's

weightisnow

assumed

tobe 40.008 {40/(100-0.02)} percent, B's weightis25.005 percent,C'sweightis 30.006percent,andthecash weightis

now

4.981 percent. IfStockA

has a4

percentretum

forthe period, themarket

retum

is3 percent, theIbbotson Associatesretuinon

long-termcorporatebonds

is2percent,and

theTreasurybillrateis 1 percent,thenthecopycat

retum

is 3 percent(.03=

(40.008*0.04+

25.005*0.03+

30.006*0.02+

4.981*0.01)/100).At

leastone

possiblemeasurement problem

ariseswiththis computationmethod.Momingstar

does notnecessarilysimultaneouslyreport equity portfolioweights

and

the overallassetallocationfrom

which

we

setbonds and

cashweights. Thus, ifinformation isreleasedon

different dates,ourcomputationoftotalweights

may

notequal 100percent.We

therefore reweighttheholdingstoachievea consistent'The

maximum

percentage ofassetsinholdingsbelowthisthresholdis 16.4percentinSample 1,and 21.9 percentinSample2.

outcome.

For

example,suppose

Momingstar

releases equity portfolioweightsthatdisaggregate95percentofaftind'sequityholdingsatyear-end, whilealsoreportingthatthefund's overall asset

allocation is

97

percent equityand

3 percentbonds

forthemonth

priortothe year-end.The

portfolioweights

would

be

adjustedby

theratio 100/(95+

3), leaving thetotal equityholdingsat 96.9 percent(95/98)

and

thebond

holdingsat 3.1 percent(3/98)of

thefund. Inpractice,thereareno

more

thansixteen days,

on

average,between

thedatesof

portfolioand

asset allocation disclosure, sowe

suspectthatthe inconsistencies associatedwiththedifferential dating arelimited. Further, theaveragedifference

between

thesum

of

the portfolioequityweightsand

thereported allocationtoequitiesisonlyone

percent.The

SEC

allowsfimdssixtydays followingtheend

oftheperiodtodisclosetheirholdings.We

thereforebeginestimating returnstothecopycatfund

two months

aftertheend

ofthereporting period.For

example, amutual

fund withacalendaryear-endmust

discloseitsyear-endportfolioholdingsby

theend of

February. Itmust

make

a similar reporton

itsholdingslateinthesecond

quarterby

theend

of

August. Therefore, thecopycatftind

retums

fortheMarch

-August

periodusetheprimitiveftind'sportfolioholdings reportedatthe

end

of

February,and

copycatfund retums

forSeptember

-February usetheprimitive fund's disclosure

from

lateAugust.The

estimatedcopycatfundretums

foreachof

theseperiodsarethen

compared

withtheprimitivefund'sretumsforthesame

period.Our

assumptionthat thecopycatfiindcan onlytracktheprimitiveftind'sportfolio

from

thesemiannualmandatory

disclosure isconservativebecauseifthe primitiveflmd

makes

voluntary disclosures,thecopycatftindcantrackitsassetholdings

more

closely.We

assume

thattheexpensesincurredby

copycat funds equaltheexpensesofthe

Vanguard

TotalStockIndexfund. Thisisan index ftmdthatinvestsinbothlargeand

smallcapitalization stocks,

and

we

view

its expensesasillustrativeof

thecostsapassively-managed

copycatftind

might

incur.We

will demonstratebelow

that ourqualitative findingswithrespect to theperformance

differentialsbetween

primitiveand

copycat fundsarerelatively insensitivetomodest

changesinourassumptions abouttheexpensesof copycatfunds.

We

reportmonthly

returndifferentials, Apre-expenseandAnd, foreachofthe sixmonths between

thedisclosure dates ofthe primitive fund.

Because

thecopycat ftind'sportfolioholdingsshouldstraymore

from

theprimitive fund'sholdingsas thetime since thelastdisclosure increases, theremay

be

some

informationinthe patternsof

retum

differentialsfordifferentmonths.We

alsoreportcumulativereturndifferentials forthe

one

tosixmonth

intervalsbetween

thesedisclosures.3.

Data

Sample and

Fund

SelectionThe

potential netretum

advantageof

a copycatfiindisgreatest fora primitive fitnd thathasahigh expenseratio.

Such

fimdsmight

be,butarenotnecessarily,engaged

inmore

researchthanotherfunds. If

one

were

goingtointroduce acopycatftind intothemutual fund marketplace,itwould

benatural touseahighexpense fundas a primitive, sinceitshighexpenses

would

offer thegreatestpromiseforthecopycat,through it'slow-coststrategy,tooutperform.

For

thisreason,we

begin ourempirical analysisby examining

asample

of

large equity funds with highexpenses.To

assess therobustnessof ourfindings,

we

repeat the analysison

a broadersample

offunds.We

focuson

equityfundsbecauseitisrelativelyeasy,usingthe

CRSP

tapes, totracktheretum

on

thesefluids' investments. Inpractice,thereisno

reasona copycatfund needstobe concerned

aboutthe availabilityofCRSP

data.The

copycatstrategycouldeasily

be

appliedtofundsthatholdmore

exoticassets,providedtheinformationdisclosedby

theprimitivefundmade

itpossibleforthecopycatmanager

toidentifytheunderlyingassets inthe primitive fund'sportfolio.We

draw

oursample

from

theequitymutual

ftindsincludedon Momingstar's

July1992

Principiadatabase.

Because

CRSP

onlyreports returns forequitysecuritieson

domestic stock exchanges,we

eliminate internationalequity funds.

We

alsoexcludesmallcapitalization handsand

specialtyfundsfrom

our sample; thesecouldbethe subject

of

separate,follow-on studies.Our

sample

restrictions limitoursample

universeto812

funds.We

draw two samples

offtindsfrom

thisuniverse.^The

High-Expense

Fund

Sample

.The

firstsample

comprisesthe20

fundsthat appeartomeet

most

closelythe definitionoflarge,diversified equityfunds with largeinvestorfees.The

sample

^We

supplementedourinitialsample,whichwascollectedby hand from 1992-93Momingstar

reports,withadatabasesuppliedby Momingstar,Inc. for1993-1999.

excludes fundsthatinvestin assetsotherthan equities

and

cash. Furthermore,thecash allocationmust

belessthan 1 percentofallinvestments.

We

exclude funds with saleschargesequaltozeroand

expense ratios lessthan 1 percent.The

sample

alsoexcludes indexfunds,funds withassetsoflessthan$200

million,

and

flindswithmore

thanhalftheirassetsallocatedtoequitiesinone

industry.For

these20

mutual

funds,we

collecteddatafrom

Momingstar

forallof

theSEC-mandated

semiannualreportingperiods

between

1992 and 1999.' Since ourdatasetspansjustoversixyears,disclosures occur twiceeachyear,

and

we

have

twentyfiinds,we

would have

amaximum

of

roughly240 (=20*6*2)

observationson fund

disclosure. Infact,we

have

asomewhat

smallersample

—

188disclosures.We

have

notaddressedissuesconcerning survivorship biases for theflindsinour sample, since

we

arenotcomparing

returnsforthesefiindswithotherfunds orthebroad market, butratherwith a setofhypotheticalcopycat

fundsthataretracking thefundsinour sample.

The

Broader

EquityFund

Sample.Our

secondsample

islargerand

isdrawn

withfewerrestrictions. Itincludes the largest 100flinds(by netassetvalue)thatallocate lessthanfortypercent

of

theirassets tobonds,preferredstock or convertiblesecurities.

As

withtheprevious sample, index fundsareexcluded,

and

thedatacome

fi^om theSEC-mandated

semiannualreports for1992 -1999, availablethrough

Momingstar.

Appendix

A

liststhesetof fundsforboththehigh-expense fiindsample and

thebroaderequityfiindsample.

We

define an observationforthepurpose of oursample

sizeas afunddisclosure.

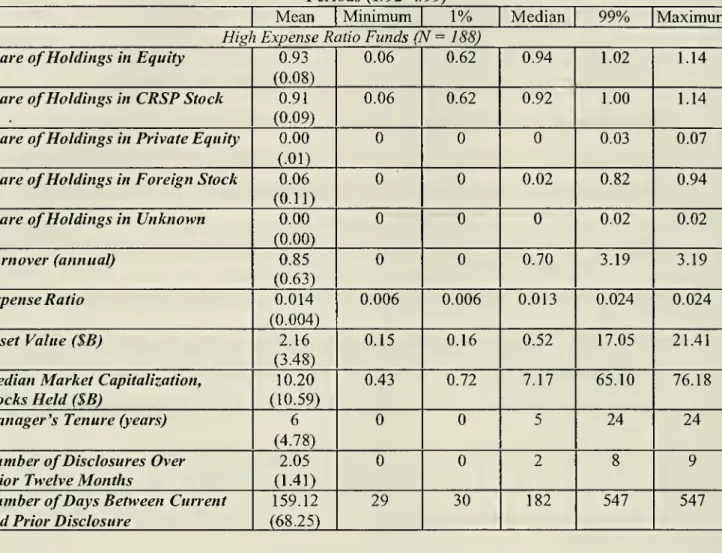

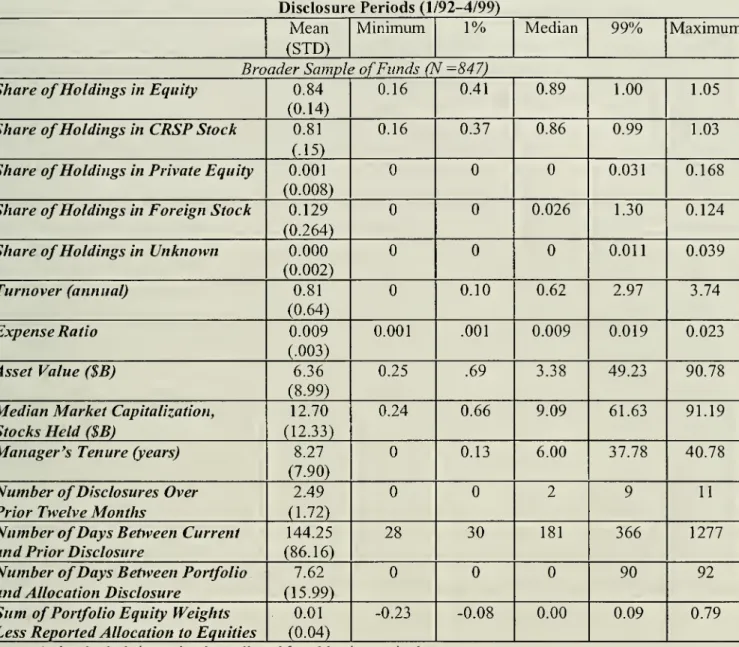

Table 1 providesdescriptivestatisticsfor the

two

fund samples.On

average, equitiestrackedby

CRSP

comprise91 (81)percentofthehigh-expense(broader) sample'sportfolios. Forthemedian

flindsineach sample, the analogousstatisticsare

92

percentand86

percent, respectively.Some

funds ineachsample

havemore

than 100 percentof

theirassets inequity; this reflectslevered equitypositions.'Theearliestpossible reportingperiod-endfor thissampleisJanuary31, 1992,so thesix-monthbuyand hold

copycat calculations

commence

April 1, 1992. Thelatestpossiblereportingperiod-endfor thissampleisApril30,1999,so thesix-monthbuyand hold copycatcalculationsendon

December

31,1 999. Thissamplecutoffimpliesthat 1999only has3 fundsforsample 1 and 23 fundsforsample2.

The

final sampledoesnot necessarilyreflectalloftherestrictivescreensineveryperiod. Ifafundmettherestrictions inJuly 1992,itwasincludedinthesample

evenifatothertimesduring1992- 1999itdid notmeettherestrictions.

Average

turnoveris similar,at 85and

81 percent, respectively,inthetwo

samples.Funds

inthehighexpense

sample have

annual expensesthataverage 1.4percentof

NAV,

versus0.9percentfor thebroader fiandsample.On

average, thehigherexpense

ratio fiindsaresmallerthan thoseinthebroader sample,holdslightlysmallercompanies,

and

employ

newer

portfoliomanagers.The

funds inthehighexpense

ratio

sample have

a slighdylongerperiodbetween

disclosuresofportfolioholdingsand

asset allocation.The

averagenumber

ofdisclosures toMomingstar

overtheprevious twelve months,and

theaveragedifference

between

thesum

of

the portfolio equity weightsand

thereportedallocationto equities, aresimilarforthe

two

samples.4. Empirical Findings

In thissection,

we

reportourresultson

therelative returnson

copycat fundsand

on

theirprimitiveactively-managedfunds.

We

beginby

reportingourfindings for thesample

of high-expensefunds,

and

we

thenmove

on

tothebroadersample

ofequityflinds.We

concludeby

reporting theresultsof

aregression analysisof

the factorsthatexplainthedifferentialbetween

copycatand

primitivereturns.4.1 Resultsforthe

Sample

ofHigh Expense

RatioFunds

Table 2

summarizes

ourfindingson

relativereturnson

fundsinthehighexpenseratiogroup

and

theircopycats. Panel

A

reportsmean

and

median

returnsineachofthesixmonths between one

disclosuredate

and

the next,while panelB

presents cumulativeresultsforperiodsofbetween one and

sixmonths.

The

firstand

secondrows

presentsummary

statisticson

returns forbothprimitiveand

copycatfunds,while thethird

and

fourthrows

present returndifferentialsbetween

thetwo

setsoffunds.Row

three considers returndifferentialsbefore expenses, while

row

fourconsidersthedifferential netof

expenses.

The

mean

primitive returnisgreaterthanthemean

copycatfundreturninall butone

ofthe sixmonths.

However,

only inmonth

6isthe return differentialsignificant atthe.05 levelusinga two-tailedtest.

(We

usetwo-tailedteststhroughoutthe paper.) Neithertheabsolutenorthemedian monthly

returndifferenceever exceeds

20

basispoints.Mean

differencesremainfairly constantoverthesixmonths.Consistentwith deteriorationinthe copycats'abilitytotracktheirunderlyingprimitive funds, the

difference

between

the copycatand

theprimitivefiindreturns increasesovertime.The

standarddeviationofthe

monthly

differencesbetween

the primitiveand

thecopycatreturn,while notshown

inthetable,averages

80

basispointsinthefirstthreemonths

aftertheinformationdisclosureand

rises to 110basispointsinthelastthreemonths.

The

averageabsolutemonthly

return differences(alsonotreported)alsoincrease

from 50

basispointsinmonth

1 to80 basispointsinmonth

6. Similarly, the correlationbetween

actualand

copycatreturnsdeclinesslightlyduringthesixmonths.The

correlation coefficientforthe

two

returnsaverages 0.98 duringthefirstthreemonths

aftertheinformationdisclosureand

0.96duringthenextthreemonths.

When

boththe primitiveand

copycatfundreturns are adjustedfor theirestimatedmonthly

expenses, the copycatfiindsoutperform theprimitivefundsinfourofthesixmonths.

However,

thespread remainsinsignificantly different

from

zeroexceptinmonth

4.The

absolute valuesofthemean

return differences

remain

atorbelow 20

basispoints.^Panel

A

inTable 2presentsretumsfor individualmonths between

portfoliodisclosuresby

primitive ftmds. Panel

B

translatesthesemonthly retums

intocumulative buy-and-hold retums.Descriptive statisticsareprovided for

retums

over one- through six-month holdingperiods.The

key

questionthattheseresultscan address concernsthe statisticalsignificanceofthecumulativereturn

differential

between

theprimitiveand

copycatflmds.The

tableshows

thatthe differencebetween

theprimitive

and

copycatfiindretums

attheend of

thesix-month holdingperiod, netof

expenses,isnotsignificantlydifferent

from

zero.The

mean

differenceattheend

ofsixmonths on

thebefore-expensereturnis

42

basis points,and

thisdifferential isstatisticallysignificantlydifferentfrom

zero.Thus

theprimitive funds

eam

ahigherreturnthanthe copycats.On

a net-of-expensebasis,however,

thecopycatIn futurework

we

plantodevelopmore

sophisticatedmeasuresoftherelativeriskinessoftheprimitiveand copycatfunds, includingboththevarianceofretums andthecovariancebetweentheretums andthemarketportfolio.

The

results arerobusttotheassumptions abouttheretumsgeneratedbynon-equityinvestments.We

computedretumstoprimitiveand copycat funds underdifferentassumptions abouttheretumstonon-equityassets,suchas

fundreturnexceedstheprimitivefundreturn

by

an averageof24

basispoints,and

we

cannotrejectthenullhypothesisthatthe

two

cumulativereturnsare equal.The

differencesbetween

the primitiveand

thecopycat fundreturns

grow

largerasthe return horizonislengthened.The

onlystatisticallysignificantdifferenceincumulativereturnsbefore expenses occurssix

months

afferthe informationdisclosure.^The

resultsfrom

thehighexpense

ratiosample

indicatethat acopycatfund cantracka primitivefund

closely forup

tosixmonths

followingportfolio disclosures. Returndifferencesbetween

thecopycatand

theassociatedprimitivefundarestatisticallyinsignificantregardless of whetherwe

deductnone of

theprimitiveftind'sexpenses,orall

of

theseexpenses,from

itsreturns. Thisindicatesthatourfindingsareunaffected

by

choicesof

X,the fractionof

the fund'sexpensesthat areattributabletoresearchexpenses,inequation(3)above. If

we

includedthe tax coststhattaxable investors face asaresultof

turnover

by

activelymanaged

fiinds,thenet-of-expensereturnadvantageforcopycatfundswould

become

even

larger.4.2 Results forthe

Broader

Sample of

EquityFunds

Table3 presentsbothindividual

month

returnsand

cumulative returnsforthe847

observationsinour broader

sample

of

actively-managedfunds.Our

findingsfrom

thehighexpenseratiosample

carryovertothebroader

sample

as well. Table3shows

thatwhen

we

ignore expenses, primitivefiindsoutperformtheirassociatedcopycat fundsin five

of

thesixmonths between

disclosureepisodes.(The

return reversal occursinthethird

month

afterthe disclosure,when

we

estimate the averagereturnon

thecopycat fimdsto

be

greaterthanthaton

theprimitive fiinds.)The

differenceinmonthly

returns,however,

isneverstatisticallysignificantly different

from

zero,and

it isneversubstantivelyverylarge.When

fund expensesaredeductedfrom

the returnsof boththe primitiveand

copycat funds, themean

differenceinzeroreturnandassumingthatallnon-equityassetsearnedtheequityindexreturn. Theseassumptionsdid notaffect

ourbasic findingthatcopycatreturnsandprimitivefundreturns are notstatisticallysignificantlydifferent.

*Toaddressthe potentialproblemsassociatedwithasynchronousreportingofportfolioweights andthe overall allocationtoequities,

we

repeatedouranalysisexcludingtheone percent of funds withthe largest differences betweentheirportfolioweightsforequitiesandtheiroverallassetallocationto equities. Fortheremaining 179 observationsinthehighexpense sample,theabsolute differencewaslessthanor equaltoeightpercentagepoints, whichgives us greaterconfidencethatthecopycatfund'sassetallocationmimicstheunderlyingmutualfund's. TheconclusionsfromPanels

A

andB

of Table2 arenot affectedbythissamplerestriction.the

monthly

returnsisnegativefor fiveof

sixmonths, butthedifferenceisstatisticallysignificantonlyinmonth

three.The

copycatfiindsgeneratehigher net-of-expensereturnsinallmonths, exceptthesixthmonth,

between

disclosuredates.The

cumulativereturnsinthelower panel of Table3show

thatbefore expenses,theretumstoholdingprimitive ratherthan copycat fundsareverysimilar. Aftersix

months,

thereisonlyathirteenbasispoint difference,

on

average,between

thetwo

setsof

retums,and

thisdifferenceisnotstatisticallysignificantly different

from

zero.When

we

compute

the difference inretums

netof

expenses,however,the averagereturn

on

the copycatfiindsishigher thanthe averagereturnon

theprimitivefiinds,and

we

canrejectthe nullhypothesisthat this differentialiszero.

Most

of

thedifferentialreturn infavorof

thecopycat fimds

emerges

inthefirstfourmonths

aftertheinformation disclosure. Aftersixmonths,thecumulative

retum

differentialis 25 basispointsinfavorofthecopycatfiinds.The

evidenceforthebroadersample of

funds providesstrongersupportfortheview

that copycatfundscan outperformtheirprimitive funds, netof expenses, thanthe

comparable

resultsforthesample ofhigh

expense

ratiofiinds. This appearstobe due

to thegreatersample

size,and

correspondinglysmallerstandarderrors,inthebroaderfiindsample.

The

cumulativeretum

differentialbetween

the primitiveand

thecopycatfiinds,netof expenses,is similarinthe

two

samples.4.3 Investigating theSource

of

Retum

DifferencesThe

summary

statisticsinTables2and

3 offerinsighton

theviabilityof

copycatfiindsasacompetitive altemativetotheirprimitivefiinds,butthey

do

notprovideany

insighton

the factorsthatcontributeto largerorsmaller

retum

differentials.To

explorethis issue,we

relatethecumulativeretum

differential beforeexpensestoa smallset

of

characteristicsoftheprimitivefiind.These

characteristics,while chosenina

somewhat

arbitraryfashion,aredesigned tocaptureboth factorsthatmight

mechanically leadtodifferences

between

thecopycatand

primitive fiindretum, aswell as factors thatmight

make

itmore

difficultfor thecopycattotracktheprimitive fiind.We

alsorepeatedthisanalysisonasubsampleof fundsthatmeasureassetallocationmore

precisely,and againour conclusionsdidnotchange.Table4presents the resultsofordinaryleastsquares regressions in thisspirit.

While

the analysisisnotmotivated

by

a tightly-specifiedmodel of

returndifferentials,thefindingsshould providesome

guidancefor future

model

development.The

dependentvariableforthe regressionsinthefirstcolumn

ofTable

4

isthepre-expensesix-month cumulativereturndifferential.The

estimatesintheupper

panelcorrespond tothehigh-expensefund sample, whilethoseinthelowerpanel,applyto thebroader sample.

The

explanatoryvariables include thepercentageof

stocksthatwe

were

able to findon

theCRSP

returntapes,turnover, theprimitivefund'sexpenseratio,itstotal assetvalue, the capitalizationofthe

companies

thatthefiindholds,

dummy

variables foreachyear,and

a variablecapturingthemanager'stenure.Inboththehigh-expense

and

broaderfimd samples,we

find thatthedifferenceinpre-expensereturns

between

the primitivefundand

thecopycatisdecreasinginthepercentageof

fiind assetsinvestedin equities covered

by

CRSP.

Thisresultindicatesthatwhen

the copycatflind isabletopositivelyidentifya higherfi-actionoftheprimitive fund's assets,thecopycatfund's return iscloserto thatofthe

primitive fund. Greateridentifiabilitydecreasestheability

of

aprimitive fundmanager

toearn superiorreturns.

Most

oftheother variables thatwe

includeintheregressionmodel have

astatisticallyinsignificanteffect

on

the returndifferentialbetween

primitiveand copycatfiinds.The

secondcolumn

of Table4

presents theresultsofestimatingmodels

inwhich

the dependentvariableistheabsolutevalue

of

thepre-expensereturndifferentialbetween

theprimitiveand

thecopycatfiind. In this case,

we

again find thatthe shareof

the portfoliothatconsistedof

CRSP-identifiableequitiesisnegatively associatedwiththis

measure

of

the variationbetween

theprimitiveand

thecopycatfiind.

The

effectisstatisticallysignificant inboth thehigh-expensesample

and

inthebroader sample, butitis

much

largerinthehighexpense sample.There

are also otherstatisticallysignificantcovariatesinthiscase.

We

find, forexample,thattheabsolutevalueof

thereturn differential isincreasingintheprimitivefiind'sturnoverrate.

Copycat

fimdson

averagetracktheprimitivefluidreturnslesswellwhen

the primitivefiindsexhibithighturnover. This

makes

sense; thecopycatfimdmanager

ischasinga"faster

moving

target"when

theprimitivefiindhasahighertumover

rate.We

alsofind,inthebroadersample,thathigherexpenseratiosfortheprimitivefundsare associatedwithlargerabsolute return

differentials

between

the primitiveand

thecopycatfiinds, beforeexpenses.The

resultsin thissection arestrictly descriptive. Nevertheless,they providesome

guidanceon

the potential efficacyof copycat fundsintracking the returnsofactively

managed

equity funds.We

do

notfind

any

largedifferencesbetween

the returnsof

the primitivefundsand

thecopycat fimds inoursample,

and

we

uncover

plausible patternsinthetypeof

actively-managed fundsthatcopycatsarelikelyto

have

themost

successintracking.5. Conclusions

Inthispaper,

we

constructhypothetical "copycat" fundsthat willmimic

the portfoliooftheassociated "primitive" fundeach timetheprimitivefunddiscloses itsportfolioholdings.

We

findthatfora

broad sample

ofdiversifiedU.S. equitymutual

funds overthe1992-1999

period, theaveragereturnsbefore expenses

on

thecopycatfimdsarelower

thanthecorrespondingreturnson

the primitivefiands.Whether

we

canrejectthenullhypothesisthatthetwo

setsof retumshave

thesame

mean

issensitivetoour choiceof

sample

withrespecttoprimitive funds.We

rejectthe equalityof

before-expenseretums ina

sample of

high expenseratiofunds,whilewe

do

notreject thisequalityforabroadersample

of

funds.However,

theretumsnetof expenses,which

are theretums

availabletoinvestors inmutual

fiinds,arehigher

on

thecopycat funds thanon

the primitivefiinds. Thisistrue forbothsamplesof

funds,althoughwe

onlyrejectthenullhypothesisof

equalretums

forthebroadsample

offunds.The

disparitybetween

thenet-of-expense retums

on

thecopycatand

primitivefundsclearlydepends

on

theassumptionthatwe

make

abouttheexpensesassociatedwithmanaging

acopycatfimd.We

assume

thatthese expenseswould

be comparable

totheexpensesof

currentindex fimds;iftheexpenseswere

actuallylarger, thecorresponding

retum

differentialwould

besmaller.Our

findings suggest thatcopycat fimdshave

the potentialtogenerateretums

thatare roughlycomparable

totheretumson

theprimitivefundsthattheyaredesignedtomimic. This suggeststhatone

ofthecostsassociatedwith financialdisclosures,

namely

theprospectof

competitorstradingon

theinformationthatsuch disclosure revealsabouttheprimitive fund'sportfolio,

may

be substantial.We

have

nottriedtoexplain

why

investorsholdactivelymanaged

equity funds,and

we

have

not contributedtothedebate

on whether

actively-managedfiinds, orcopycat funds basedon

thesefiinds,can outperform broadmarket

benchmarks.These

are large issuesthatgo

wellbeyond

the current paper.However,

we

have

shown

thatwhatever

benefitinvestors inactivelymanaged

fundsthinkthattheyreceivefrom

theseinvestments, intermsof subsequent retums, can beimitatedtoa substantialdegree

by

copycatfiinds.Our

analysis considersonlyone

ofthe potential costs offinancialdisclosure, anditdoes notattempttoquantify

any

of

the potential benefits associatedwithdisclosure.As

such,itcannotbeconstruedasprovidingultimateguidance

on

thedesign ofdisclosure regulations,although itmight

be aninputtotheregulatory process.

Two

featuresof our study designmay

leadustooverstate the returnon

thecopycatftind,relativetothe primitivefiind.

Both

reflectouranalysis ofhypotheticalcopycatfiinds,ratherthancopycatfiindsthatactuallyoperateinthe

market and

thatprimitivefundsrecognizeand

respondto.First,ifthe securitypurchases

by

the copycat funddriveup

the prices ofsecuritiesalreadyheldby

theprimitivefiind,thentheprimitivefund isina sense "frontrunning" purchasesby

thecopycatfiind.This couldincrease the

retums

on

theprimitivefiind,particularly in thefirstmonth

afterportfolioholdingsare disclosed.

There

issome

evidencethatfront-mnningofstockpurchasesby

mutualfiindscangenerate substantialretums.

Gasparino

(1997)reportsthattheVanguard

Group

stoppedreportinginformationaboutthenetcash flowsinto itsfundsbecausethirdparties

were

apparentlyusingthisinformationto "frontrun"

Vanguard

funds. Ifapotentialinvestorknew

thelargestholdingsof

agivenVanguard

fund,and

healsoknew

thatthefundhad

experienceda largecash inflow,he

might beabletoidentifysecuritiesfor

which

therewould

be substantialdemand

inthenearfiiture. Fidelity,which once

released dailyinformation

on

the sizeof

some

of

itssectorfiinds,hassimilarlystoppedreportingthisinformationbecauseit

may

be

of usetoinvestorswho

aretryingto profitfrom

thefund's prospective purchases.We

are notaware of any

evidencethatquantifies thepotentialretumstofront-running.Second,ifcopycat funds

were

an importantfeatureof

themutual fundlandscape,actively-managed

fundsmight

take actionsthatwould

reducetheinformationcontentof

theirsemiannualdisclosures. Thisisanalogoustotheproblem, described in

Lemer

(1995),thatfacesa firmthatplanstopatenta

new

technology,when

thedetailsrevealedinthe patent applicationwillprovide valuableinsightstopotential competitors.

Ifthe

managers

ofprimitivefundscouldcamouflage

theiractual portfolioholdings,thiswould

potentiallyincrease the returndifferential

between

theprimitiveand

thecopycatfunds. If activelymanaged

flindsdo

earnpositivereturns asaresultoftheirinformation, itwould presumably

raisethereturn

on

the primitivefimdsrelativeto thatofthecopycats.There

isno

consensusatpresenton

theextentto

which

mutual fluidmanagers engage

in"window

dressing,"orchangingthe composition oftheirportfoliosnearthe

end of

a reporting period.The

attractivenessof

window

dressingdepends

on

thetransaction costsassociatedwith

moving

inand

outofa particularsecurity,includingany

costsof

executionassociatedwiththebid-askspread.

Such

a trading strategymight

make

senseforlargecompanies

whose

shares are actively tradedinliquidmarkets.For

smallerand

less liquid securities,we

suspectthatthetransaction costs

would

outweigh

thegainfrom

dissemblingfrom

competitors.Musto

(1999)findsevidence of

window

dressingamong money

market

fiindmanagers.The

potential benefitsfrom

securityselectionintheequitymarkets probably exceeds thecomparable

benefitsinthe short-termmoney

market; thissuggeststhatwindow

dressingmay

alsoexistinthe equityfund market,asO'Neal

(2001)suggests.

While

thesetwo

considerationsmay

leadustounderstate the returnadvantage ofthe primitivefiind,

one

other factoris likely tooperateinthereversedirection. Thisisourassumptionthatthecopycatonlyobtainsinformationaboutthe primitive fund's holdingseverysixmonths. Inpractice,

we

know

thatmany

activelymanaged

fundsrevealinformationmore

oftenthanthis, andpresumably

a copycatfiindtryingto

mimic

such afiindwould

beable to track the primitive'sretum

performancemore

closely.The

issuesthatwe

have

discussedwithrespecttomutual fiindsalsoarise ina varietyofothercontexts

where

imitation can reducethevalueof

initialresearch investments.Tax

sheltersprovideone

example. Sullivan(1999)writesthat "taxshelterscannot becopyrighted. Eventually, the

word

getsouttootherclients, tocompetitors,

and even

totheIRS. It ishardto justify large feesfortaxshelters thatmany

firmsmarket

..."One way

thatlaw and

accounting firmsthatdesigntaxsheltersattempttoreducethis diffusionof informationis

by

askingpotential clients to sign confidentialityagreements before theyleam

aboutthedetailsof

a potential shelter.These

agreementspresumably

slow,butdo

not prevent, theultimate diffusionofinformation.

Our

analysisof one

potentialcostof

information disclosure,and

ourdiscussionofother potentialcosts,bears

on

onlyone

side ofthebalancethatmust

ultimatelybeusedtodetermine optimal regultaorypolicywithrespecttoinformationdisclosure.

The

most

importantneed

forpolicydesignin thisareaisinformation

on

the potential benefitsthatinvestorsreceivefrom

information disclosure. Thispresumably

requiresinformation

on

thelikelihoodthatfundmanagers

willchange

theirinvestmentobjectiveswithoutinformingshareholders,

and on

the levelofdisclosurethatwould

takeplaceiftherewere no

regulatoryrequirementsfor disclosure.

REFERENCES

Admati,

Anat and

Paul Pfleiderer (2000), "ForcingFirms

toTalk: Financial DisclosureRegulationand

Externalities,"

Review

ofFinancial Studies 13,479-519.Carhart,

Mark,

Ron

Kaniel,David

Musto,and

Adam

Reed

(2001), "LeaningfortheTape:Evidence

of

Gaming

Behavior

inEquityMutual

Funds," Journalof Finance(forthcoming).Fairley, Juliette(1997),

"Keeping

More Under

TheirHats,"New

York

Times

(June 15),p.F7.Foster,

George

(1980), "Externalitiesand

FinancialReporting," Journal of Finance35, 521-533.Freeman, John

P.and

StewartL.Brown

(2001)."Mutual

Fund

Advisory

Fees:The

Costof

Conflictsof

Interest,"Journal of Corporation

Law

26

(3),610-673.Gasparino, Charles(1997). "Vanguard's

Cutback of

Fund

Data

May

Mean

ItFears aMarket

Drop,"Wall

StreetJournal(October 14).

Gigler,

Frank

(1994), "Self-enforcingVoluntaryDisclosures,"Journalof Accounting Research

32:2,224-240.

Gmber,

Martin J. (1996), "AnotherPuzzle:The Growth

ofActively-Managed

Mutual

Funds,"Joumal

ofFinance

51, 783-810.Laderman,

JeffreyM.

(1999),"A

Mutual

Fund

That

LetsItAllHang

Out,"BusinessWeek

(September

27), p. 126.

Lakonishok,Josef, AndreiShleifer,RichardThaler,

and

RobertVishny

(1991),"Window

Dressingby

Pension

Fund

Managers,"American

Economic Review

81 (May), 227-231.Lemer,

Josh(1995), "Patenting intheShadow

of Competitors,"Joumal

ofLaw

and

Economics

38 (2),463-495.

Manne, Henry

G. (1966). InsiderTradingand

the StockMarket

(New

York:The

FreePress).Musto, David

K. (1999),"Investment DecisionsDepend

on

PortfolioDisclosures,"Joumal

of Finance 54 (June),935-952.O'Neal,

Edward

(2001),"Window

Dressingand

EquityMutual

Funds,"mimeo, Babcock

Graduate Schoolof

Management,

Wake

Forest University.Sullivan,Martin (1999),

"One

ShelterataTime?,"

Tax

Notes

(December

6), 1226-1229.Verrecchia, Robert. (1983), "Discretionary Disclosure,"

Joumal

ofAccounting and

Economics

, 5, 179-194.Wermers, Russ

(2001),"The

Potential Effectsof

More

FrequentPortfolioDisclosureon Mutual

Fund

Performance," Investment