HAL Id: hal-00577003

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00577003

Submitted on 16 Mar 2011

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

INCREASED RISK OF COLORECTAL CANCER

Sylvie Sacher-Huvelin, Emmanuel Coron, Marianne Gaudric, Lucie Planche,

Robert Benamouzig, Vincent Maunoury, Bernard Filoche, Muriel Frederic,

Jean-Christophe Saurin, Clement Subtil, et al.

To cite this version:

Sylvie Sacher-Huvelin, Emmanuel Coron, Marianne Gaudric, Lucie Planche, Robert Benamouzig, et al.. COLON CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY VERSUS COLONOSCOPY IN PATIENTS AT AVERAGE OR INCREASED RISK OF COLORECTAL CANCER. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Wiley, 2010, 32 (9), pp.1145. �10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04458.x�. �hal-00577003�

For Peer Review

COLON CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY VERSUS COLONOSCOPY IN PATIENTS AT AVERAGE OR INCREASED RISK OF

COLORECTAL CANCER

Journal: Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics

Manuscript ID: APT-0511-2010.R1

Wiley - Manuscript type: Clinical Trial

Date Submitted by the

Author: 24-Aug-2010

Complete List of Authors: Sacher-Huvelin, Sylvie; Institut des Maladies de l'Appareil Digestif, University Hospital, CIC

Coron, Emmanuel; Institut des Maladies de l'Appareil Digestif, University Hospital, Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutritional Support

gaudric, marianne; CHU COCHIN, GASTROENTEROLOGY planche, lucie; chu hotel dieu, biostatistics

benamouzig, robert; chu bobigny, gastroenterology maunoury, vincent; CHRU LILLE, GASTROENTEROLOGY Filoche, Bernard; St. Philibert Hospital

FREDERIC, MURIEL; CHU NANCY, INTERNAL MEDICINE AND DIGESTIVE PATHOLOGY

Saurin, Jean-Christophe; chu Edouard Herriot, gastroenterology Subtil, Clement; CHU BORDEAUX, GASTROENTEROLOGY Lecleire, Stéphane; CHU ROUEN, GASTROENTEROLOGY Cellier, Christopher; HEGP, GASTROENTEROLOGY

Coumaros, Dimitri; CHU STRASBOURG, GASTROENTEROLOGY Heresbach, Denis; Centre Hospitalier Regionale et Universitaire, Service des Maladies de l’Appareil Digestif

Galmiche, Jean Paul; Nantes University, Gastroenterology

Keywords:

Colorectal cancer < Disease-based, Capsule endoscopy < Topics, Colonoscopy < Topics, Diagnostic tests < Topics, Screening < Topics

For Peer Review

COLON CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY VERSUS COLONOSCOPY IN PATIENTS AT

AVERAGE OR INCREASED RISK OF COLORECTAL CANCER

Sylvie Sacher-Huvelin*1-2, Emmanuel Coron*2, Marianne Gaudric**3, Lucie Planche**4, Robert Benamouzig5, Vincent Maunoury6, Bernard Filoche7, Muriel Frédéric8, Jean-Christophe Saurin9, Clément Subtil10, Stéphane Lecleire11, Christophe Cellier12, Dimitri Coumaros13, Denis Heresbach 14 and Jean Paul Galmiche 1,2

1

CIC 0004, INSERM, Nantes, France

2

Department of gastroenterology, IMAD, CHU and University of Nantes, France

3

Department of gastroenterology, CHU Cochin, Paris, France

4

Department of biostatistics, CHU Nantes, France

5

Department of gastroenterology, CHU Bobigny, Paris, France

6

Department of gastroenterology, CHRU Lille, France

7

Department of gastroenterology, CHU St Philibert, Lomme, France

8

Department of internal medicine and digestive pathology, CHU Nancy, Vandoeuvre les Nancy, France

9

Department of gastroenterology, CHU E Herriot, Lyon, France

10

Department of gastroenterology, CHU Bordeaux, France

11

Department of gastroenterology, CHU Rouen, France

12

Department of gastroenterology, HEGP, Paris, France

13

Department of gastroenterology, CHU Strasbourg, France

14

Department of gastroenterology, CHU Rennes, France

* Equal contribution ** Equal contribution

Corresponding author: Prof JP Galmiche

Postal address : Department of gastroenterology, IMAD, CHU HOTEL DIEU, 44093 Nantes cedex 1, France email: jeanpaul.galmiche@chu-nantes.fr Tel: 33 2 40 08 30 28 Fax: 33 2 40 08 31 68 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

ABSTRACTBackground - Aim Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) is a new, non-invasive technology. We

conducted a prospective, multicentre trial to compare CCE and colonoscopy in asymptomatic

subjects enrolled in screening or surveillance programmes for the detection of colorectal

neoplasia.

Methods Patients underwent CCE on day one and colonoscopy (gold standard) on day two.

CCE and colonoscopy were performed by independent endoscopists.

Results 545 patients were recruited. CCE was safe and well-tolerated. Colon cleanliness

was excellent or good in 52% of cases at CCE. Five patients with cancer were detected by

colonoscopy, of whom two were missed by CCE. CCE accuracy for the detection of polyps ≥

6 mm was 39% (95% CI 30-48) for sensitivity, 88% (95% CI 85-91) for specificity, 47% (95%

CI 37-57) for positive predictive value and 85% (95% CI 82-88) for negative predictive value.

CCE accuracy was better for the detection of advanced adenoma, in patients with good or

excellent cleanliness and after re-interpretation of the CCE videos by an independent expert

panel

Conclusion Although well-tolerated, CCE cannot replace colonoscopy as a first line investigation for screening and surveillance of patients at risk of cancer. Further studies

should pay attention to colonic preparation.Clinicaltrial.gov number NCT00436514.

Key words: colon capsule endoscopy; colonoscopy; screening; colonic neoplasia, accuracy. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

INTRODUCTIONColorectal cancer (CRC) is a major cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide. The

screening and surveillance of patients with average (asymptomatic, 50-74 years old), or

increased (asymptomatic with a personal or family history of polyps and/or CRC), risk is

based on the detection and removal of adenomatous polyps. In many countries, colonoscopy

is considered to be the standard procedure for screening and surveillance. However,

colonoscopy has some limitations including invasiveness, discomfort and embarrassment for

the patient, the need for short-term hospitalisation and, finally, a relatively high cost. These

inconveniences may limit the utility of colonoscopy, especially in screening strategies where

acceptance of the test is of the utmost importance. Similarly, such disadvantages can impact

on compliance in patients who require surveillance because of a personal or family history of

colonic neoplasia. Capsule endoscopy is a new technology for the investigation of the small

bowel, which has been developed very successfully during the last decade. Recently, a

specific capsule device has been developed for colon endoscopy and proof-of-concept

studies have shown encouraging results1-4. In fact, none of these studies were designed for the assessment of colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) as a screening test, as most of the

enrolled patients were symptomatic and/or hospitalised for known or suspected colonic

diseases.

We, therefore, conducted a prospective, multicentre trial, in order to assess the diagnostic

yield of CCE compared with colonoscopy in carefully-selected, asymptomatic patients at

average or increased risk of CRC. Because the likelihood of cancer is higher in polyps ≥ 6 mm in size, our main criterion of judgement was the proportion of individuals with polyps of

this size (or with CRC) detected by CCE, as compared with colonoscopy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS Study group

The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Pays de la Loire and the

study was registered in the EudraCT database (n° ID RCB 2007-A00056-47) and in the

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

database Clinicaltrial.gov (n° : NCT00436514). Written, informed consent was obtained from all patients. Adults patients were enrolled prospectively from April 2007 to July 2009 in each

of the 16 French academic centres if they fulfilled one of the following two criteria: (i) healthy,

asymptomatic individuals 50 to 74 years old who accept colonoscopy in the context of a

screening programme (average risk group); (ii) asymptomatic patients with a personal or

family history of CRC or polyps, but without colonoscopy during the preceding three years

(increased risk group). The main exclusion criteria were ; the presence of dysphagia;

symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction; recently-complicated colonic diverticulosis;

advanced heart or kidney failure; the presence of a cardiac pace-maker or other implanted

electro-medical device; pregnancy.

Colon capsule endoscopy and colonoscopy

The characteristics of PillCam colon (Given Imaging Ltd) have been described previously5. Briefly, the colon capsule uses the same technology as the small bowel corresponding

devices, but is slightly longer. It measures 11 x 32 mm and has dual cameras, located at

both ends, allowing image acquisition with a frame rate of 4 frames per second.

The colon preparation procedure has been adapted from the conventional PEG

preparation used for colonoscopy in order to ensure cleanliness, but also propulsion of the

capsule through the GI tract. Patients underwent colon preparation as previously reported by

others1. However, during the first part of this trial, we did not recommend a clear liquid diet the day before CCE. This recommendation was introduced after the first interim analysis

planned in the study protocol (see results). Colon cleanliness was assessed using a

four-grade scale, as in previous studies, and results were expressed as excellent, good, fair or

poor. The same classification was applied to assess colonic preparation during colonoscopy

(after flushing of the colon, if required).

Colonoscopy was performed under general anaesthesia (as is standard practice in

France). All detected polyps were removed and sent to the local Pathology Department for

routine histology. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

Study design (Table 1)The study was conducted prospectively and its design followed the STARD

recommendations6. Patients at average or increased risk of CRC were enrolled in each centre and informed consent was obtained after explaining the objectives and modalities of

the protocol. During this first visit, patients were instructed about the three-day, low-residue

diet and the colon preparation procedure (four litres of PEG) required prior to CCE. Patients

were hospitalised for approximately 36 hours. CCE was performed at approximately 10:00

a.m., one hour after the ingestion of the fourth litre of PEG. Domperidone, sodium phosphate

and bisacodyl suppository were administered as previously described (Table 1). After

completion of CCE (excretion of the capsule or at least 10 hours after capsule ingestion)

patients were allowed to eat a light, low-residue snack in the evening of this first day.

Colonoscopy was performed the morning of the second day, approximately three hours after

administration of an additional litre of PEG to ensure optimal cleanliness.

In each centre, one to three experienced endoscopists performed all colonoscopies, while capsule videos were interpreted separately by one single independent endoscopist per

centre. CCEs and colonoscopies were performed by endoscopists, unaware of each others

findings. All capsule endoscopists received specific training using CCE videos before the

beginning of the trial. The training course (one full day) consisted of showing some

characteristic videos in the morning (with explanations of the method of CCE video interpretation, especially polyp size estimation) followed by a validation of the training by three test-video sequences in the afternoon. The first author certified the validation of the training session by the following criteria; (i) adequate knowledge of the software capabilities, (ii) ability to detect more than 90% of lesions ≥6 mm, and (iii) estimation of polyp size.

Polyps and lesions seen during colonoscopy were recorded according to their

location and size, eventually, with the use of open-biopsy forceps.

CCE videos were interpreted separately at a reading speed of approximately eight

frames per second. Investigators were instructed to read the images taken from the proximal

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

camera and then from the distal one. The sizes of polyps detected were estimated visually,

according to the distance separating the colonic wall and the camera, as in previous trials.

However, contrary to Van Gossum et al, no correction of this rough estimate was applied.

Tolerability and safety were recorded during hospitalisation and, finally, at a follow-up

visit approximately 30 days after the patient was discharged from the clinic. During this visit,

patients were invited to express their opinions concerning CCE and colonoscopy using a

Visual Analogic Scale (VAS) for both procedures.

Statistical analysis

As in previous trials, colonoscopy was considered as the gold standard and per-patient

comparisons were made considering different primary and secondary criteria. However,

because colonoscopy is not a perfect gold standard, we planned an additional analysis using

a modified gold standard, taking into consideration the false positive results of CCE. Indeed,

so-called “false positives” are in fact “true positives” if the presence of a polyp is confirmed by

a second colonoscopy. We also made the same assumption when a second independent

video reading of the discrepant findings between colonoscopy and CCE, performed by an

expert panel, clearly confirmed the presence of the image of a polyp ≥ 6 mm.

According to the STARD recommendations, the analysis was performed on an

intention-to-diagnose basis (with technical failures considered to be negative results of CCE).

The per-protocol cohort represents the patients who completed the study successfully and

who underwent both CCE and colonoscopy with complete examination.

Contrary to previous studies, which were based only on exploratory statistics, the aim

of this trial was to test the non-inferiority of CCE as compared with colonoscopy. Considering

the perspective of screening and surveillance, we assumed that an excellent negative

predictive value (no more than 5% difference with colonoscopy) would be indispensable for

such a test to be useful in practice. In addition, even if CCE was inferior to colonoscopy, we

assumed that the difference in terms of sensitivity between CCE and colonoscopy should not

exceed 20%. Using an α risk = 5%, a β risk = 10% and an expected prevalence of polyps ≥ 6

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

mm of 15% (primary criterion of judgement), we calculated that a sample size of 514 (550

with losses) would be necessary to test our non-inferiority hypothesis. An interim analysis

was scheduled to be performed when 1/5 of the recruitment had been achieved, in order to

assess colon cleanliness and safety. Finally, the following tests were used for the final

analysis : the Mac Nemar test, the chi-square test and the Student’s t-test on paired data. A

p value < 0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

RESULTS Patients

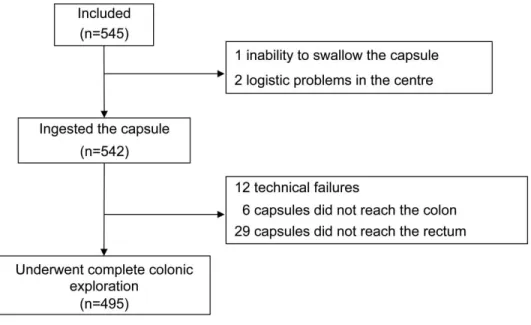

The flow distribution of the 545 patients enrolled in the trial is shown in Fig. 1. The

demographic characteristics of the intention-to-diagnose cohort are shown in Table 2.

Propulsion of the capsule and colon cleanliness

Interim analysis of colon cleanliness was performed after enrolment of the first 105 patients7. Although there were no safety concerns, the proportion of patients with good or excellent

preparation was only 55%. Thus, the protocol was amended and the recommendation3 concerning the use of a completely clear liquid diet the day before CCE was adopted.

Despite this change in the preparation, there was no improvement in the quality of

preparation (data not shown) and results concerning cleanliness were pooled in the final

analysis. As indicated by Fig. 2, colon cleanliness was considered to be excellent or good in

52% of patients at CCE and in 83% of cases at colonoscopy. In most patients (91%), the

capsule was excreted within 10 hours of ingestion.

Prevalence and accuracy of detection of polyps

Table 3 shows the per-patient prevalence of polyps and CRC detected by colonoscopy and

the diagnostic performance of CCE. Overall, colonoscopy detected more patients with polyps

than did CCE. Hence, 311 (57%) patients had polyps of any size detected by colonoscopy

compared with 249 seen at CCE (46%; p < 0.0001). Regarding polyps ≥ 6 mm and ≥ 10 mm,

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

the corresponding figures were 112 (21%) versus 94 (17%) (p = 0.097) and 43 (8%) versus

29 (5%) (p = 0.03), respectively.

Five patients with CRC were detected by colonoscopy compared with only three

detected by CCE. The two missed cancers were located in the sigmoid colon and rectum,

and both were relatively large tumours (35 mm and 15 mm, respectively). Re-reading of the

videos of these two cancer cases failed to detect any abnormality that could have been

missed by previous readers. The quality of preparation was good in one case and fair in the

other case.

For the 545 patients, the CCE accuracy of detection of polyps ≥ 6 mm or CRC was

39% (95% CI 30-48) for sensitivity, 88% (95% CI 85-91) for specificity, 47% (95% CI 37-57)

for the positive predictive value (PPV) and 85% (95% CI 82-88) for the negative predictive

value (NPV). The non-inferiority between CCE and colonoscopy for the detection of polyps ≥

6 mm was not acceptable for sensitivity (absolute difference -51% (95% CI -58;-43) nor for

NPV (absolute difference -13% (95% CI -16;-10).

For 118 patients, the results of CCE and colonoscopy were discordant concerning

the primary criterion of judgment. All of the CCE videos of these discordant cases were

reviewed by the expert panel. This reinterpretation of the capsule videos improved the

diagnostic yield of CCE, with sensitivity increasing to 57% (95% CI 48-66), specificity to 95%

(95% CI 93-97), PPV to 73% (95% CI 63-82) and NPV to 90% (95% CI 87-92).

With respect to advanced adenomas (i.e. adenomas ≥ 10 mm and/or with a villous

contingent and/or high grade dysplasia), the sensitivity of CCE was better, at 72%, and an

NPV of 94%.

Overall, the results were almost the same in the screening and surveillance cohorts

(data not shown) and in the intention-to-diagnose and per-protocol cohorts (data not shown).

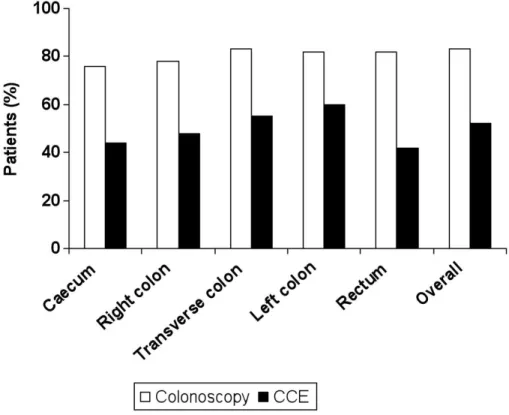

Effect of cleanliness on the accuracy of CCE

As shown in Fig. 3, CCE accuracy was better in the group of patients with good or excellent

cleanliness compared with those with poor or fair preparation. In the well-prepared patients,

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

the NPV increased to 88% (95% CI 83-92) for polyps ≥ 6 mm and 98% (95% CI 96-99) for

polyps ≥ 10 mm, but sensitivity remained low (53% [95% CI 39-67]) for polyps ≥ 6 mm).

Effect of modifying the gold standard on the accuracy of CCE and colonoscopy

The consideration of false positives of the CCE procedure as true positives, if confirmed by

the expert panel (or, in four cases, by a second colonoscopy), minimised the differences in

accuracy between CCE and colonoscopy for the diagnosis of polyps ≥ 6 mm. Indeed, the

sensitivity and specificity of CCE increased to 51% (95% CI 42-59) and 94% (95% CI 91-96),

respectively, compared with 83% (95% CI 76-89) and 100% for colonoscopy. Similarly, PPV

and NPV were 72% (95% CI 63-81) and 85% (95% CI 82-89), respectively, for CCE versus

100% and 95% (95% CI 93-97) for colonoscopy. Thus, even in the best-case scenario, CCE

was unable to satisfy the conditions of non-inferiority, as compared with colonoscopy.

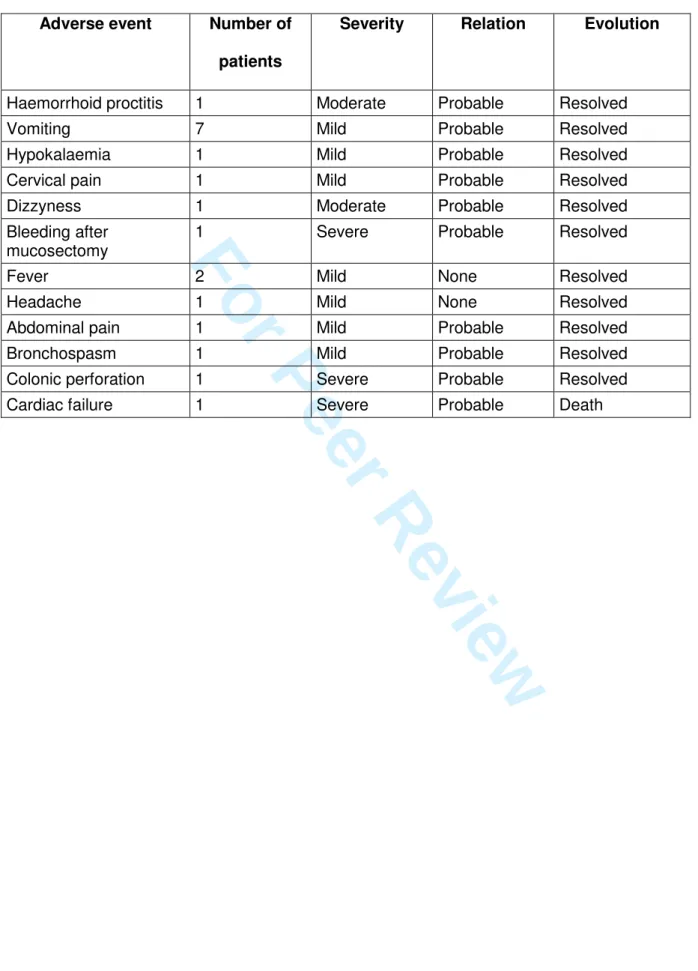

Safety and tolerability

Nineteen adverse events were reported. Most of these were of mild or moderate severity

(Table 4). Only three severe adverse events occurred, which were either potentially related

to bowel preparation. No severe adverse event was related to the capsule itself.

The comparison of VAS scores showed a slight (probably not clinically relevant)

statistical difference in favour of CCE compared with colonoscopy (8.74 ± 1.56 versus 8.25 ±

2.00; p < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

This study, the largest trial of CCE reported to date, confirms the feasibility, safety and

tolerability of this method for the screening and surveillance of patients at average or

increased risk of CRC. Despite an excellent NPV, the sensitivity of CCE was lower than in

previous studies conducted in patients with already-known, or suspected, disease.

Therefore, the hypothesis of non-inferiority of CCE compared with colonoscopy is ruled out

by the present data.

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

One strength of this study was the enrolment of a representative population of

patients referred for screening or surveillance. The demographic characteristics of our cohort

are indeed those expected in this context8-11, although we enrolled fewer average-risk than increased-risk subjects. The proportion of polyps detected was slightly higher than initially

expected, which may, ultimately, have resulted in a minor underestimation of the NPV of

CCE. However, the issue concerning the results of this study is not NPV, but rather

sensitivity. There are several reasons that may have contributed to a lower sensitivity of CCE

as compared with previous trials. The poor quality of bowel preparation in nearly half of the

subjects is a plausible explanation, because colon cleanliness directly influences the

diagnostic performance of CCE, as shown by Van Gossum et al3 and confirmed by the present study. However, our findings are in agreement with those recently reported (in an

abstract form) by Spada et al12; indeed, in their series of 92 patients, only 43.5% of them had an adequate (good or excellent) bowel preparation. Accordingly the sensitivity of CCE in this

study was somewhat lower (56%) that in previous series1-4. In our study, the type of population enrolled (asymptomatic subjects) could be one of the factors that negatively

influenced colon cleanliness. This does, however, reflect real-life conditions, where patients

are prepared out of the clinic. In contrast, colonoscopy was performed on the second day in

the clinic and in more stringent conditions; it is, therefore, not surprising that the preparation

was considered good or excellent at colonoscopy in 83% of the cases. Moreover, the

flushing of residual amounts of faeces may occur during colonoscopy (but not during CCE),

which may further improve the quality of exploration by colonoscopy. In the group of patients

with excellent or good colon cleanliness the sensitivity of CCE, although improved, remains

clearly insufficient. In this respect it is important to underline that, in the first published

meta-analysis13 of CCE trials, only data (including our preliminary results) referring to the best level of bowel preparation were included. The last meta-analysis published by Spada et al 14found

a sensitivity of 68% for significant findings (polyps ≥ 6mm and/or ≥ 3 polyps). In fact, after excluding one study for heterogeneity, the sensitivity falls to 62%.

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

To the best of our knowledge there has been no validation study of the scale used for CCE colonic preparation assessment. We used the same scale as in previous CCE studies

1-4, 12

. We cannot completely exclude that, apart from true differences in the quality of preparation between centres, some part of the variability could be related to inter-observer variations in the assessment method employed. This may also contribute to an explanation of the wide variability in colonic preparation quality scores reported in the meta-analysis14, as the proportion of patients who were well prepared ranged from 27% up to 89%.

Another reason for the lower performance of CCE in our study might be insufficient

experience of the endoscopists in reading the CCE videos. This hypothesis is partly

supported by the fact that the diagnostic yield improved upon re-reading of the videos of

discordant cases by an expert panel, but again it did not reach the performance

characteristics required for a screening or a surveillance procedure. However, we did not

detect, in the context of this trial, any evidence of a learning curve effect. Indeed, no difference was observed in terms of diagnostic performance when we compared the group of 70 patients initially enrolled with the group of patients recruited later (data not shown). In addition, there was no difference between the low-volume recruitment centres and the largest ones. The differences between centres were actually more directly related to the overall quality of colonic preparation achieved in different hospital settings.

Finally, even after changing the gold standard definition to test the best possible

scenario, the difference between CCE and colonoscopy remained outside the maximal

interval accepted for the non-inferiority hypothesis. Hence, our negative conclusion

concerning CCE sensitivity would seem to be robust and was unchanged by the several

post-hoc analyses performed in selected subgroups. Similarly, the results were not better in

the per-protocol cohort or in the average-risk compared with increased-risk patients.

The main criterion of judgement adopted in this trial (i.e. the proportion of patients

with polyps of at least 6 mm or CCR) is the same as in other studies. It is justified by the fact

that the risk of cancer is very low (but not zero) below this size threshold. As with other

imaging technologies, such as CT-scanning (virtual colonoscopy), CCE does not allow the

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

removal of polyps and, thus, it has been proposed that small, diminutive polyps do not need

to be removed, due to the very low risk of malignancy 10, 15, 16. In contrast, the detection and removal of advanced adenomas is of crucial importance. In this context, it is important to

stress the excellent NPV and the better sensitivity of CCE, reaching 72% for the whole cohort

(and 78% in the well-prepared patients). CCE might, at least, be an option when colonoscopy

is contra-indicated or incomplete for technical reasons and further trials are in progress to

test this potential “second-line” indication of CCE.

All diagnostic parameters were calculated on a per-patient analysis. Therefore it is not surprising to see that sensitivity is better for small than large polyps. Indeed, the number of small polyps was higher than that of large polyps (for example, 177 out of 857 polyps had a diameter of at least 6 mm compared to 54 for those of at least 10 mm). Therefore, the likelihood of detecting a polyp in a patient is greater for small polyps, because their mean number per patient is higher (0.32) than for large polyps (0.10).

One limitation inherent to all current capsule endoscopy technologies is the difficulty of assessing polyp size accurately. Although we applied the same principles as in former studies, it must be recognised that the method used in all CCE studies provides an imperfect estimate, which clearly may have affected the validity of our primary criteria of judgement. The second generation of capsule endoscopes will, hopefully, integrate a better system with respect to the measurement of polyp size. Our study was not designed to assess inter/intra-observer variability but within the panel of experts who reviewed the discordant cases the inter-observer agreement was 71% (data not shown)

Finally, it must be acknowledged that we used a first generation of colon capsule.

Very-recently, a new device has been developed, which presents several technical

improvements, including a larger field-of-view, a better sampling rate and, of greater

importance, a grid for more objective measurement of polyp size. A recent trial of this new

device17 conducted in a population with various colonic pathologies, reported higher sensitivity than in our study but, again, the population was not representative of a screening

population, as in our trial.

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

In summary, in this trial, which involved the largest population enrolled for colon

capsule evaluation to date, and which was conducted in average- and increased-risk,

asymptomatic patients, we did not establish the non-inferiority of CCE as compared with

colonoscopy. Further studies should pay particular attention to colonic preparation in

conditions compatible with real life. Quality control of video reading is probably required after

an initial training period. Improving the technology of the device is, on its own, probably

insufficient to fulfil the requirements of a test which is useful for screening and surveillance in

patients at risk of CRC. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

References1. Eliakim R, Fireman Z, Gralnek IM, et al. Evaluation of the PillCam colon capsule in the detection of colonic pathology: results of the first multicenter, prospective, comparative study. Endoscopy 2006;38:963-70.

2. Schoofs N, Devière J, Van Gossum A. PillCam colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy for colorectal tumor diagnosis: a prospective pilot study. Endoscopy 2006;38:971-7.

3. Van Gossum A, Munoz-Navas M, Fernandez-Urien I, et al. Capsule endoscopy versus colonoscopy for the detection of polyps and cancer. N Engl J Med 2009;361:264-70.

4. Gay G, Delvaux M, Frederic M, et al. Could the colonic capsule PillCam colon be clinically useful for selecting patients who deserve a complete colonoscopy?: Results of clinical comparison with colonoscopy in the perspective of colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1076-86.

5. Galmiche JP, Coron E, Sacher-Huvelin S. Recent developments in capsule endoscopy. Gut 2008;57:695-703.

6. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:1-12.

7. Sacher-Huvelin S, Le Rhun M, Sébille V, et al. Wireless Capsule Colonoscopy Compared to Conventional Colonoscopy in Patients At Moderate or Increased Risk for Colorectal Cancer. Interim Analysis of a Prospective Multicenter Study [abstract]. Gastroenterology 2009;69 (suppl 1):A53.

8. Le Rhun M, Coron E, Parlier D, et al. High resolution with chromoscopy versus standard colonoscopy for the detection of colonic neoplasia: a randomized study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4: 349-54.

9. Johnson CD, Chen MH, Toledano AY, et al. Accuracy of CT colonography for detection of large adenomas and cancers. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1207-17.

10. Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med 2003;349: 2191-200.

11. Harewood GC, Lieberman DA. Colonoscopy practice patterns since introduction of medicare coverage for average-risk screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:72-7.

12. Spada C, Hassan C, Riccioni ME, et al. Pillcam colon capsule endoscopy for colon exploration : a single centre Italian experience [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:AB203.

13. Rokkas T, Papaxoinis K, Triantafyllou K, et al. Meta-analysis evaluating the accuracy of colon capsule endoscopy in detecting colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:792-8.

14. Spada C, Hassan C, Marmo R et al. Meta-analysis shows colon capsule endoscopy is effective in detecting colorectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:516-522. 15. Bond JH. Clinical relevance of the small colorectal polyp. Endoscopy 2001;33:454-7.

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

16. Külling D, Christ AD, Karaaslan N, et al. Is histological investigation of polyps always necessary? Endoscopy 2001;33:428-32.

17.

Eliakim R, Yassin K, Niv Y, et al. Prospective multicenter performance evaluation of the second-generation colon capsule compared with colonoscopy. Endoscopy 2009;41:1026-2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60For Peer Review

Table 1: Study protocol: colonic preparation and drug administered (prokinetic and boosters)

Regimen I (n = 232) Regimen II (n = 313)

Day -3 to -2 Low residue diet Idem

Day -1 Low residue diet Liquid diet

18:00 - 21:00 3 litres Colopeg® Idem

8:00 - 9:00 1 litre Colopeg®

9:45 - 10:00 20 mg Motilium® & PillCam

Day 0 12:00 Booster I (45 ml NaP)* Idem

15:30 Booster II (30 ml NaP)**

18:00 10 mg Bisacodyl suppository**

18:30 Low-fibre snack

Day +1 6:00 - 7:00 1 litre Colopeg®

After 10:00 Traditional colonoscopy Idem

* Pending verification that PillCam left stomach with RAPID real-time viewer ** If PillCam was not expelled from anus

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

Table 2: Demographic characteristics of the intention-to-diagnose cohort

Average risk* Increased risk* Total

N = 163 N = 376 N = 545*

Age (years; mean range) 60 (27-79) 60 (25-86) 60 (25-86)

Gender F/M 76/87 162/214 306/239 Family history N (%) Polyps 0 63 (12) 63 (12) CRC 0 184 (34) 184 (34) Personal history N (%) Polyps 0 213 (39) 213 (39) CRC 0 18 (3) 18 (3)

*6 missing data items concerning the criterion of inclusion: average/increased risk

Age and gender were not statistically different between groups

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

Table 3: The prevalence of lesions detected by colonoscopy in the 545 patients in the accuracy analysis and the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and

negative predictive value of CCE for the detection of these lesions.

Colonoscopy Colon Capsule Endoscopy

Prevalence Sensitivity Specificity Positive Predictive Value Negative Predictive Value N of patients (%) % (95 % CI) Polyp Any size 311 (57.1) 58 (53-64) 71 (65-77) 73 (67-78) 56 (50-62) ≥ 6 mm 112 (20.6) 39 (30-48) 88 (85-91) 47 (37-57) 85 (82-88) ≥ 10 mm 43 (7.9) 35 (21-49) 97 (96-99) 52 (34-70) 95 (93-97) Adenoma Any size 192 (35.2) 61 (54-68) 63 (58-68) 47 (41-53) 75 (70-80) ≥ 6 mm 80 (14.7) 44 (33-55) 87 (84-90) 37 (27-47) 90 (87-93) ≥ 10 mm 36 (6.6) 39 (23-55) 97 (96-99) 48 (30-66) 96 (94-97) Advanced adenoma* Any size 54 (9.9) 72 (60-84) 57 (53-62) 16 (11-20) 94 (92-97) ≥ 6 mm 45 (8.3) 49 (34-63) 86 (83-89) 23 (15-32) 95 (93-97) ≥ 10 mm 36 (6.6) 39 (23-55) 97 (96-99) 48 (30-66) 96 (94-97) Colorectal Cancer** 5 (0.9) 60 (17-100) 100 (99-100) 60 (17-100) 100 (99-100)

* Advanced adenoma was defined as an adenoma 10 mm or larger or an adenoma with villous features or high grade dysplasia.

** All colorectal cancers were larger than 10 mm and localised, one in the caecum, one in the rectum and three in the sigmoid colon.

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

Table 4: Adverse eventsAdverse event Number of patients

Severity Relation Evolution

Haemorrhoid proctitis 1 Moderate Probable Resolved

Vomiting 7 Mild Probable Resolved

Hypokalaemia 1 Mild Probable Resolved

Cervical pain 1 Mild Probable Resolved

Dizzyness 1 Moderate Probable Resolved

Bleeding after mucosectomy

1 Severe Probable Resolved

Fever 2 Mild None Resolved

Headache 1 Mild None Resolved

Abdominal pain 1 Mild Probable Resolved

Bronchospasm 1 Mild Probable Resolved

Colonic perforation 1 Severe Probable Resolved

Cardiac failure 1 Severe Probable Death

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

Figure LegendsFigure 1: Flow of patients. Intention-to-diagnose and per-protocol cohorts.

Figure 2: Proportion of patients (%) with excellent or good colonic preparation at colon

capsule endoscopy and colonoscopy.

Figure 3: Capsule accuracy of capsule endoscopy in patients with good or excellent

cleanliness. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

AcknowledgmentsThe authors thank the following people for their contribution in this study:

The expert panel for the re-reading of CCE:

Bernard Filoche, Gérard Gay, Vincent Maunoury, Sylvie Sacher-Huvelin

The investigators, listed from highest to lowest number of patients enrolled in the study:

Jean Paul Galmiche, Marc Le Rhun, Emmanuel Coron, Mathurin Flamant, Marianne

Gaudric, Stanislas Chaussade, Romain Coriat, Robert Benamouzig, Bakhtiar Bejou,

Jean-Christophe Saurin, Thierry Ponchon, Jérôme Dumortier, Marie George Lapalus, Jeanne

Boitard, Clément Subtil, Patrice Couzigou, Elise Chanteloup, Eric Terreborne, Michel

Delvaux, Muriel Frédéric, Philippe Ducrotté, Stéphane Lecleire,Christophe Cellier, Joel

Edery, Camille Savale, Dimitri Coumaros, Dimitri Tzilves, Denis Heresbach, Pierre Nicolas

d’Halluin, Denis Sautereau, Anne Lesidaner, Franck Cholet, Thierry Barrioz.

The following people participated in the coordination of the study:

Stéphanie Bardot, Kafia Belhocine, Kevin Galery, Eliane Hivernaud, Anne Omnes, Véronique

Sébille, FabienneVavasseur

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

Financial support and Statement of interestAuthor’s declaration of personal interest

Robert Benamouzig is a board membership of Given Imaging.

Jean Paul Galmiche is a consultant of Given Imaging.

Declaration of funding interest

This study was funded by a national grant from the French Ministry of Health and sponsored

by the Délégation à la Recherche Clinique (DRC) of the university hospital of Nantes.

The study benefited from some limited logistic support from Given Imaging, including the use

of an already-available eCRF and a discount price for capsules. The design of the trial and

the monitoring and analysis of data were, however, conducted independently by the sponsor

(DRC) and the authors.

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

STARD checklist for reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy (version January 2003)

Section and Topic Item #

On page #

TITLE/ABSTRACT/ KEYWORDS

1 Identify the article as a study of diagnostic accuracy (recommend MeSH heading 'sensitivity and specificity').

2

INTRODUCTION 2 State the research questions or study aims, such as estimating diagnostic accuracy or comparing accuracy between tests or across participant groups.

3

METHODS

Participants 3 The study population: The inclusion and exclusion criteria, setting and locations where data were collected.

4

4 Participant recruitment: Was recruitment based on presenting symptoms, results from previous tests, or the fact that the participants had received the index tests or the reference standard?

4

5 Participant sampling: Was the study population a consecutive series of participants defined by the selection criteria in item 3 and 4? If not, specify how participants were further selected.

4

6 Data collection: Was data collection planned before the index test and reference standard were performed (prospective study) or after (retrospective study)?

4

Test methods 7 The reference standard and its rationale. 4 8 Technical specifications of material and methods involved including how

and when measurements were taken, and/or cite references for index tests and reference standard.

5

9 Definition of and rationale for the units, cut-offs and/or categories of the results of the index tests and the reference standard.

3

10 The number, training and expertise of the persons executing and reading the index tests and the reference standard.

5

11 Whether or not the readers of the index tests and reference standard were blind (masked) to the results of the other test and describe any other clinical information available to the readers.

5

Statistical methods 12 Methods for calculating or comparing measures of diagnostic accuracy, and the statistical methods used to quantify uncertainty (e.g. 95% confidence intervals).

6

13 Methods for calculating test reproducibility, if done. NA

RESULTS

Participants 14 When study was performed, including beginning and end dates of recruitment.

4

15 Clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population (at least information on age, gender, spectrum of presenting symptoms).

7 and table 2

16 The number of participants satisfying the criteria for inclusion who did or did not undergo the index tests and/or the reference standard; describe why participants failed to undergo either test (a flow diagram is strongly recommended).

7 and figure 1

Test results 17 Time-interval between the index tests and the reference standard, and any treatment administered in between.

Table 1

18 Distribution of severity of disease (define criteria) in those with the target condition; other diagnoses in participants without the target condition.

7 and table 2

19 A cross tabulation of the results of the index tests (including indeterminate and missing results) by the results of the reference standard; for continuous results, the distribution of the test results by the results of the reference standard.

Table 3

20 Any adverse events from performing the index tests or the reference standard. 9 and Table 4 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

Estimates 21 Estimates of diagnostic accuracy and measures of statistical uncertainty (e.g. 95% confidence intervals).

7, 8, 9 and table

3

22 How indeterminate results, missing data and outliers of the index tests were handled.

7 and figure 1

23 Estimates of variability of diagnostic accuracy between subgroups of participants, readers or centers, if done.

7, 8, 9 table 3 and figures 2

and 3

24 Estimates of test reproducibility, if done. NA

DISCUSSION 25 Discuss the clinical applicability of the study findings. 9, 10, 11

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

For Peer Review

Figure 1: Flow of patients. Intention-to-diagnose and per-protocol cohorts. 85x51mm (400 x 400 DPI) 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58

For Peer Review

Figure 2: Proportion of patients (%) with excellent or good colonic preparation at colon capsule endoscopy and colonoscopy.

85x68mm (400 x 400 DPI) 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58

For Peer Review

Figure 3: Capsule accuracy of capsule endoscopy in patients with good or excellent cleanliness. 85x64mm (400 x 400 DPI) 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58