Ghanaian university student and teacher preferences for

written corrective feedback in French as a foreign

language classes

Mémoire

John Coffie Teye

Maîtrise en linguistique - didactique des langues - avec mémoire

Maître ès arts (M.A.)

Ghanaian university student and teacher

preferences for written corrective feedback in

French as a foreign language classes

Mémoire

John Coffie Teye

Sous la direction de :

Résumé

Un aspect pertinent du domaine de la rédaction en langue seconde concerne les préférences des enseignants et des élèves en ce qui a trait à la rétroaction corrective à l’écrit (RCE). Le but de cette étude était d'examiner les préférences de la RCE des étudiants (n = 106) ghanéens et des professeurs (n = 5) de français langue étrangère (FLE) au niveau universitaire. Ainsi, un plan de recherche mixte a été utilisé pour recueillir des données sur la préférence des élèves et des enseignants à l'égard de l'enseignement de la grammaire dans leur classe de rédaction, le type et la quantité de rétroaction qu'ils préfèrent, le type d'erreur sur lequel ils préfèrent donner des rétroactions et les facteurs contextuels qui portent une influence sur leurs préférences. Des questionnaires et des entrevues semi-structurées ont été utilisés pour collecter les données. Les résultats de l'étude ont montré que les étudiants et les professeurs accordaient une grande importance à l'enseignement de la grammaire et à la rétroaction sur les erreurs. Ce résultat s’accorde avec le constat de Bisaillon (1991) que chez les apprenants d’une langue seconde ou d’une langue étrangère, la maîtrise de la grammaire s’avère d’une très grande préoccupation à la différence de ceux qui rédigent des textes en langue maternelle. Comme dans les contextes d’anglais langue étrangère (Alshahrani et Storch 2014; Chung, 2015; Elwood et Bode, 2014; Hamouda, 2011), les étudiants de français langue étrangère de cette étude préféraient la rétroaction directe. Comme facteur contextuel, l’étude a également éclairé comment la formation des enseignants influence l’utilisation des stratégies de rétroaction et l’enseignement de l’écriture. Compte tenu du fait que les études antérieures sur la RCE ont trait aux contextes d’anglais langue étrangère, cette étude contribue à nos connaissances dans ce domaine à l’égard des contextes de français langue étrangère.

Abstract

The preferences for written corrective feedback (WCF) by teachers and students is one area of relevance in second language writing. The aim of this study was to investigate the WCF preferences of Ghanaian students (n = 106) and teachers (n = 5) of French as a Foreign Language (FFL) at the university level. To achieve this purpose, a mixed research design (qualitative and quantitative) was used to gather and analyse information about students and teachers’ perception of grammar instruction in their writing class, their preferred type and amount of feedback, their preferred type of error to be corrected and the contextual factors that influenced their preferences. Questionnaires and semi-structured interview protocols were used to collect the data. The results of the study show that both students and teachers accorded a great importance to grammar instruction and feedback on errors. This finding echoes Bisaillon’s (1991) contention that for second and foreign language learners, mastering the structures of the language is a major preoccupation unlike for writers in their first language who have already mastered most of the structures needed for essay writing. As in English foreign language contexts (Alshahrani & Storch 2014; Chung, 2015; Elwood & Bode, 2014; Hamouda, 2011), the FFL students of the present study preferred direct feedback. As a contextual factor, the study also shed light on how the teachers’ educational background was implicated in their approach to the teaching of writing and feedback practices. As previous studies on WCF have been limited to English foreign language contexts, this study contributes to research with respect to French foreign language contexts.

Table of content

Résumé ... ii

Abstract ... iii

Table of content ... iv

List of tables ... vi

List of abreviations ... viii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ... x INTRODUCTION ... 1 STATEMENT OF PROBLEM ... 3 1.1 Research questions ... 4 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 5 2.0 Introduction ... 5

2.1 The writing process ... 5

2.2 Relevance of second language acquisition (SLA) theory to written corrective feedback ... 6

2.3 Written corrective feedback techniques ... 9

2.4 Conclusion ... 10

LITERATURE REVIEW ... 12

3.0 Introduction ... 12

3.1 Written corrective feedback preferences in second/foreign language learning ... 12

3.2 Influence of contextual factors on written corrective feedback preferences in second/foreign language learning ... 16

3.3 Conclusion to the literature review section ... 17

METHODOLOGY ... 19

4.0 Introduction ... 19

4.1 Methodological approach ... 19

4.2 Context of the study ... 20

4.3 Participants ... 20

4.4 Data collection instruments ... 21

4.5 Data collection procedures ... 23

4.6 Data analysis ... 23

4.7 Conclusion to the methodology section ... 26

RESULTS ... 28 5.0 Introduction ... 28 5.1 Demographic information ... 28 5.2 Research question 1 ... 29 5.3 Research question 2a ... 32 5.4 Research question 2b ... 43 5.5. Research question 2c... 55 5.6 Research question 3 ... 59 5.7 Research question 4 ... 61 5.8 Research question 5 ... 66 5.9 Conclusion ... 79 DISCUSSION ... 80 6.0 Introduction ... 80

6.1 Discussion of research question 1: grammar instruction ... 80

6.2 Discussion of research question 2: ... 81

6.3 Discussion of research question 3: preferences for WCF usage ... 84

CONCLUSION ... 85

7.0 Introduction ... 85

7.1 Summary of findings ... 85

7.2 Limitations and recommendations for future research ... 87

7.3 Pedagogical implications ... 89

7.4 Conclusion ... 90

REFERENCES ... 91

APPENDICES ... 95

Appendix A: Written Expression Course Outline ... 96

Appendix B: Students’ Questionnaire ... 99

Appendix C : Teachers’ Questionnaire ... 105

Appendix D: Interview Guide for Students ... 111

Appendix E: Interview Guide for Teachers ... 113

Appendix F: Information Sheet for Implicit and Anonymous Consent ... 115

Appendix G: Interview Consent Form – Students... 117

Appendix H: Consent Form – Teachers ... 120

Appendix I: Authorization Form – Head of Department, Department of French, University of Cape Coast, Ghana. ... 123

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1: Ellis’ (2009) taxonomy of corrective feedback ... 11

Table 4.1: Overview of research questions, data collection instruments and mode of analysis. ... 25

Table 5.1: Characteristics of student participants ... 28

Table 5.2: Characteristics of teacher participants ... 29

Table 5.3: Students’ opinion about grammar instruction in L2 writing class ... 30

Table 5.4: Teachers’ opinion about grammar instruction in L2 writing class ... 31

Table 5.5 : Students’ perception of the importance of feedback in French writing class ... 32

Table 5.6 : Students' preference for amount of feedback in French writing class ... 33

Table 5.7 : Students’ opinion about correction of repeated errors ... 33

Table 5.8: Teachers’ perception of the importance of feedback in French writing class ... 34

Table 5.9: Teachers’ preference for amount of feedback in French writing class ... 34

Table 5.10: Teacher participants’ opinion about correction of repeated errors ... 35

Table 5.11: Students’ reasons for how important it is to correct errors in their French essays ... 35

Table 5.12: Students’ reasons for their preference for the amount of feedback correction in French writing class ... 37

Table 5.13: Students’ reasons for the correction or non-correction of repeated errors ... 39

Table 5.14: Teachers’ reasons for how important it is to correct errors in students’ French essays . 41 Table 5.15: Teachers’ reasons for the amount of feedback they prefer to give ... 42

Table 5.16: Teachers’ reasons for correction or non-correction of repeated errors ... 43

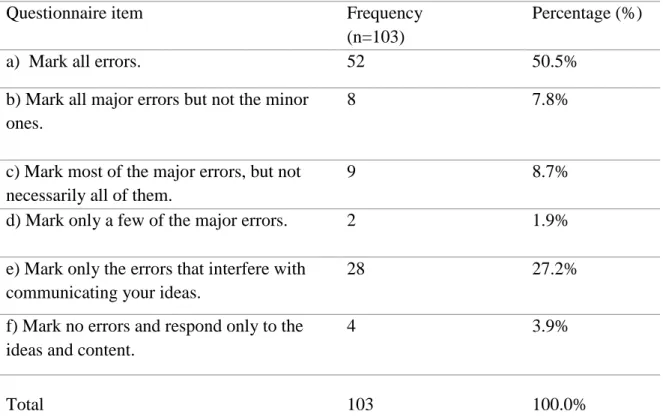

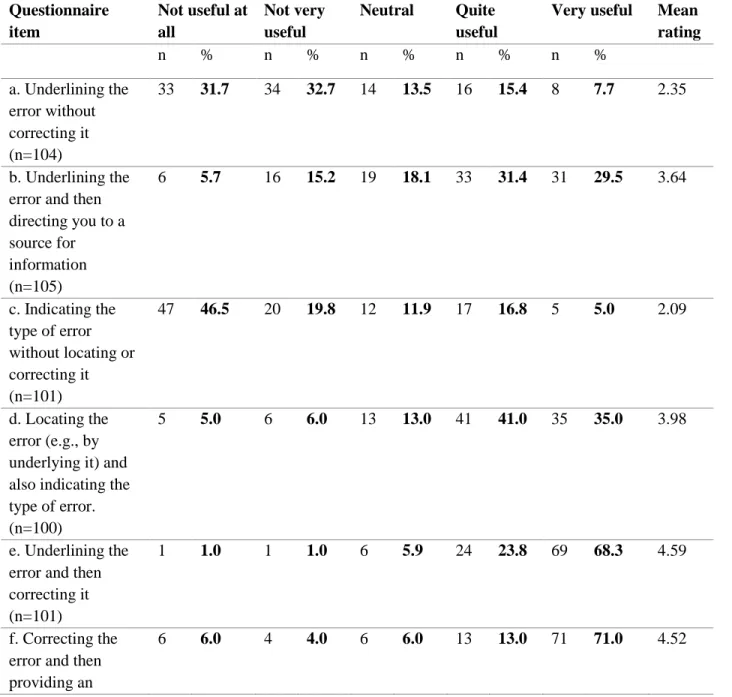

Table 5.17: Students’ preferences for different types of WCF ... 44

Table 5.18: Teachers’ preferences for different types of WCF ... 45

Table 5.19: Students’ reasons for ratings of preferences for underlining the error without correcting it ... 47

Table 5.20: Students’ explanations for ratings of preferences for underlining the error and then directing you to a source for information ... 48

Table 5.21: Students’ explanations for ratings of preferences for indicating the type of error without locating or correcting it ... 49

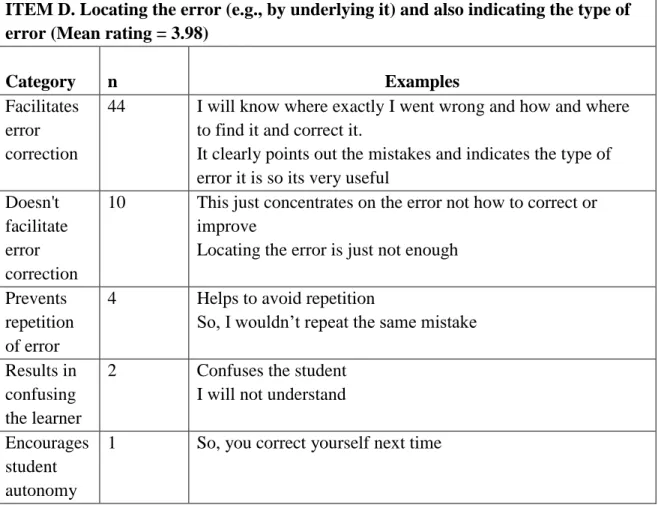

Table 5.22: Students’ explanations for ratings of preferences for the usefulness of locating the error (e.g., by underlying it) and also indicating the type of error ... 50

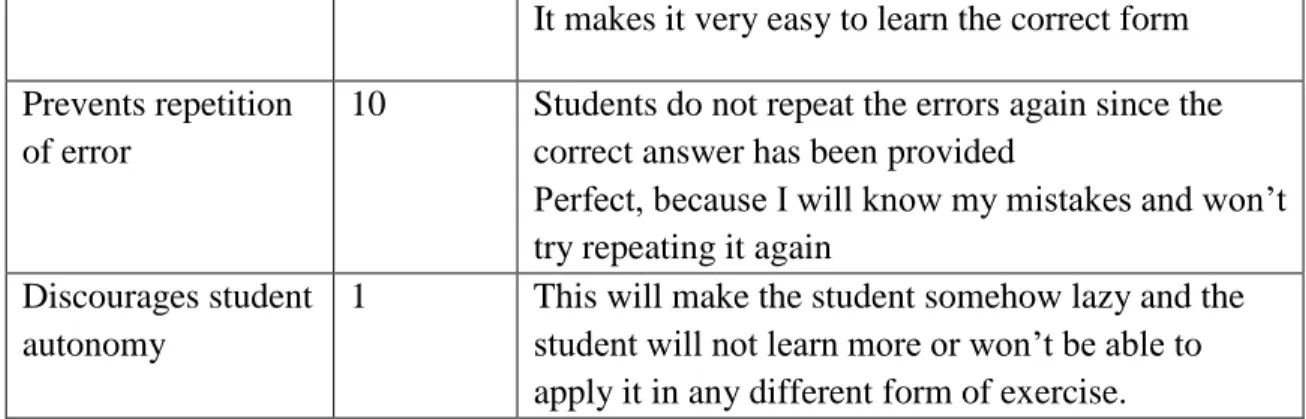

Table 5.23: Students’ explanations for ratings of the usefulness of underlining and then correcting the error ... 50

Table 5.24: Students’ explanations for ratings of the usefulness of correcting the error and then providing an explanation for the correction ... 51

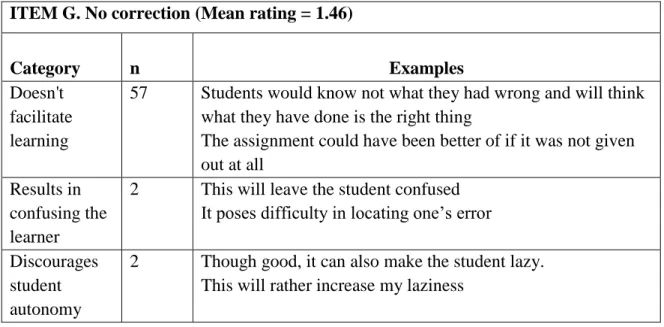

Table 5.25: Students’ explanations for ratings of the usefulness of no correction ... 52

Table 5.26: Students explanations for ratings of the usefulness of giving a comment on the content ... 52

Table 5.27: Teachers’ explanations for the ratings of preferences for usefulness of different types of feedback ... 54

Table 5.28: Students’ preferences for feedback on type of error ... 56

Table 5.29: Teachers’ preferences for feedback on types of errors ... 57

Table 5.30: Students’ explanation for the type of error to focus on ... 58

Table 5.32: Students’ level of attention to feedback ... 59

Table 5.33: Students’ preferred initiative in case of a misunderstanding of the corrections ... 60

Table 5.34: What teachers thought students should do with feedback... 60

Table 5.35: What teachers thought students should do if they did not understand feedback ... 61

Table 5.36: Students and teachers’ opinion about grammar instruction in L2 French writing class 62 Table 5.37: Students and teachers’ perception of the importance of feedback in L2 French writing class ... 63

Table 5.38: Students and teachers’ preference for amount of feedback in L2 French writing class . 63 Table 5.39: Students and teachers’ opinion about correction of repeated errors ... 64

Table 5.40: Students and teachers’ preferences for different types of WCF ... 64

Table 5.41: Students and teachers’ preferences for feedback on types of errors ... 65

Table 5.42: Students and teachers’ level of attention to feedback ... 66

Table 5.43: Students and teachers’ preferred initiative in case of unclear feedback... 66

Table 5.44: Students’ previous studies of French, the content of the writing course and the setting of their writing activities ... 68

Table 5.45: Students perception of grammar instruction and preferred feedback types ... 68

Table 5.46: Students preferred amount of feedback and the type of error to be corrected ... 69

Table 5.47: Students preferred use of feedback and opinions about feedback practice ... 70

Table 5.48: Students’ comparison of learning to write in French versus learning to write in English ... 71

Table 5.49: Students’ motivation in learning French writing ... 72

Table 5.50: Teachers’ experience teaching French writing and the content of the writing course ... 74

Table 5.51: Teachers’ perception of grammar instruction and preferred feedback types ... 74

Table 5.52: Teachers’ preferred amount of feedback and the type of error to be corrected ... 76

Table 5.53: Teachers’ preference for how students should use feedback and opinions about how feedback should be provided ... 77

Table 5.54: Teachers’ Academic Backgrounds ... 78

LIST OF ABREVIATIONS

EFL – English as a Foreign LanguageESL – English as a Second Language FFL – French as a Foreign Language SLA – Second Language Acquisition WCF – Written Corrective Feedback ZPD – Zone of Proximal Development

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to thank all those who have contributed, either directly or indirectly, to the realization of this research project.

I extend my deepest gratitude and sincere thanks to my director, Prof. Susan Parks, who has provided me with valuable assistance throughout the project. Thank you for the confidence you had in me and your support; I have learned a great deal from you.

To all my teachers during my studies at Université Laval, thank you very much for all the things you have taught me. Your wise advice will help me throughout my future career.

To all teachers of the Department of French at the University of Cape Coast, I am grateful for your contribution to my training and your collaboration during the data collection process.

To the teachers and students who participated in the research, without whom the study would have been impossible to conduct, thank you for your participation.

I thank all my family, especially, Mr. and Mrs. Sackey-Teye, my mother, my brother Francis and his wife, my sweetheart Sandra Kafui Quarshie, my uncle, Nene Asigbe, my friends, especially, Josiah Obodai Torto, Robin Couture-Matte, Duchelle Staelle Voufo, Laurelle Houeto and Richard Quansah for their suggestions and support to the achievement of this work. My heartiest gratitude to Mr and Mrs Afful-Nyarko for their invaluable help.

I am also grateful to my classmates for their help and encouragement.

INTRODUCTION

Second language writing is considered one of the important aspects of L2 learning (Bitchener & Ferris, 2012; Raimes, 1983). In this field, Written Corrective Feedback (WCF) is one of the most widely researched topics due to arguments about whether it is an important practice or not (Li, 2010; Russell & Spada, 2006). While most of these studies have investigated the effectiveness of WCF, a few have explored the preferences and perceptions of both teachers and students. Most of the studies have been in the context of English as a foreign or second language. This study, however, was conducted to investigate the preferences for Written Corrective Feedback (WCF) by Ghanaian university teachers and students of French as a foreign language (FFL). Understanding the WCF preferences of students and teachers is important because it might help to make feedback more effective to the stakeholders, especially the learner (Brown, 2012).

With respect to Ghana, the teaching of French as a foreign language is regarded as very important for purposes of communication with the outside world, especially her francophone neighbours. Ghana, a British colony previously called Gold Coast, is one of 18 countries in West Africa. Geographically, it is surrounded by three francophone countries: Togo on the east, Cote d’Ivoire on the west and Burkina Faso on the north. For administrative purposes, Ghana is divided into 10 decentralised regions. Like most countries in Africa, Ghana is a multilingual nation with over 60 languages and dialects (Lewis, 2009). 2However, English is used for all legal, administrative and official procedures and documents, and is also the language used in Ghanaian politics, education, and the media. Although English is the official language, French is also taught as a foreign language. Unlike the English language, the introduction of French into the educational system is not related to colonization. French is taught at all levels of the Ghanaian educational system (basic school, secondary school and university levels). Due to the lack of French teachers, not all basic schools teach French. It is optional at the secondary school level and the university level. Almost all the universities in Ghana offer French as a subject of study and this includes the University of Cape Coast (UCC). Generally, the teaching of French is divided into two main parts: oral and written communication. These two dimensions come with their own challenges, but this study’s focus is on the written aspect.

This research report contains seven chapters. In chapter 1, a statement of the problem particularly as pertains to WCF and its relevance for second language learning will be presented. The context for the study will also be discussed and the research questions identified. Chapter 2 will focus on the conceptual and theoretical framework which will be used to situate the research. In Chapter 3, the studies of most relevance to the present research project will be reviewed. In Chapter 4 the methodology used to carry out the study will be presented. Following this, the results of the research project will be presented and discussed in Chapters 5 and 6. The concluding part will provide an overview of the study as well as suggestions for future research.

STATEMENT OF PROBLEM

Second language writing and assessment in most educational institutions is widely accompanied by the practice of corrective feedback, and most researchers believe it helps in second/foreign language (L2) learning (Bitchener & Ferris, 2012; Li, 2010). Since written corrective feedback is intended to improve students’ linguistic accuracy, it is important to assess its effectiveness and to do that, the stakeholders as well as the practice must be examined. Ultimately, learning may be improved when feedback is effectively designed (Brown, 2012).

One of the research concerns of writing which has gained a lot of attention over the past two decades (Kang & Han, 2015) is response to students’ writing (mostly referred to as written corrective feedback, WCF). The main subject of concern in WCF research has been whether it is effective in improving L2 accuracy (Chen, Nassaji & Liu, 2016). One particular area related to the potential efficacy of WCF is the attitudes-perceptions-preferences of both students and teachers towards feedback. Many studies in their quest to understand how WCF can be rendered more effective have explored the attitudes, perceptions and preferences of students and teachers towards feedback (e.g., Alshahrani & Storch, 2014; Amrhein & Nassaji, 2010; Chung, 2015; Elwood & Bode, 2014; Hamouda, 2011). However, as will be shown in the review of the literature, research to date has mostly involved English as a foreign/second language (EFL/ESL) students and teachers. To begin to fill this gap, I will focus on WCF in the area of French as a foreign language (FFL).

Another related gap is that most of the studies did not discuss the reasons for the preferences evoked by students and teachers as well as their context. According to Evans, Hartshorn, McCollum and Wolfersberger (2010), it is vital to explore the contextual variables in WCF studies to ensure a deeper understanding of research findings. In addition, comparing the preferences of teachers to that of students is regarded as very important because differences “could create some tension as well as challenges in error correction pedagogy” (Amrhein & Nassaji, 2010, p. 116).

The foundation of this research is therefore built on the following points as discussed in the preceding paragraphs:

- Studies about WCF preferences in the context of FFL are few.

- Very few studies have examined the WCF preferences of students and teachers and triangulated the reasons behind such preferences.

- No studies have reported on WCF preferences in the Ghanaian context of FFL.

1.1 Research questions

To achieve the aim of this research which is to examine Ghanaian university level FFL students’ and teachers’ WCF preferences and reasons for these preferences, the following questions were asked:

1. How do FFL students and teachers at a tertiary level in Ghana view the role of grammar instruction in their writing courses?

2. What do these students and teachers think is the most useful and why, with respect to:

a. amount of WCF b. types of WCF

c. types of errors to be corrected

3. What do students prefer to do with the WCF feedback they receive and what do teachers think they should do with it?

4. Are there differences between FFL students’ and teachers’ preferences regarding the usefulness of grammar instruction, the different amounts of WCF, types of WCF, types of errors to be corrected and use of WCF?

5. What contextual factors influence the way teachers and students perceive writing, in particular, feedback?

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.0 IntroductionThe objective of this chapter is to discuss the conceptual and theoretical framework of the study conducted in this dissertation. For this reason, first, the writing process in second language learning will be discussed, some Second Language Acquisition (SLA) theories related to written corrective feedback will be reviewed, and the techniques of written corrective feedback presented. The purpose is to provide a broad understanding of our objective and explain how the study is related to certain SLA theoretical frameworks, specifically skill acquisition theory, sociocultural theory and the interactionist perspective.

2.1 The writing process

Most linguists note that, unlike the oral code of communication, the recipient of the written message is not present in the exchange (Vigner, 2004). The information sent is not immediately received by the supposed recipient. Writers, therefore, have no possibility of verifying whether their readers understand what they want to communicate or not. This situation is what makes writing a challenging process of communication.

Writing in an L2 is regarded as a complex process (Berg, 1999; Hanson & Liu, 2005; Zhao, 2014). According to Bisaillon (1991), writing in a native language is considerably different from writing in a second language, especially for L2 learners who have not yet mastered the language:

Il semble, en effet, qu’en langue maternelle, l’enseignant puisse présupposer que les étudiants maîtrisent 80 à 90% des structures qu’ils utiliseront dans leurs compositions. Tel n'est cependant pas le cas en langue seconde, du moins à un niveau intermédiaire. Cette différence explique en partie le fait que l'enseignant de langue seconde attire l'attention des scripteurs davantage sur les composantes linguistiques du texte, telles l'orthographe des mots ou la morpho-syntaxe, que sur les composantes textuelles ou discursives. (p. 58)

The linguistic elements of a written text therefore become a major point of focus for both students and teachers. Studies by Hayes and Flower (1980) as well as Zamel (1983) indicate that the writing process mostly involves planning, drafting, reading and revision. In

regard to their discussion of these activities, one can associate written corrective feedback with the revision part of the writing process. Revision, which comes mostly at the last stage of the writing process, involves the writer making sure his or her text is well organised, that the content is coherent and without structural or linguistic errors. Linguistic errors have been found to be of utmost importance for L2 learners (Cavanagh & Blain, 2009).

2.2 Relevance of second language acquisition (SLA) theory to written corrective feedback

Several theories have been proposed to define the process by which second language learners acquire language or in other words, develop their linguistic skills (e.g. DeKeyser, 2007; Long, 1996; Vygotsky, 1978). It would be important to explain how the point of view of some of these theories relates to the notion of WCF. To do this, I will present skill acquisition theory, sociocultural theory and the interactionist perspective on second language acquisition. Since my aim is to discuss how WCF is associated with these theories, it would be primordial to define and classify the nature of WCF as a form of explicit or implicit learning. The classification of linguistic learning/instruction as explicit or implicit is one of the elements at the basis of most SLA theories (Brown, 2007).

As defined by Brown (2007), explicit learning “involves conscious awareness and intention” while implicit learning “involves learning without conscious attention or awareness” (p. 291). The general question about these two concepts are whether they lead to the acquisition of knowledge and if so, which one is better.

2.2.1 Skill acquisition theory

According to DeKeyser (2007), skill acquisition theory is a general psychological theory of learning where learners acquire knowledge of something through an explicit process (declarative knowledge) and with adequate practice and exposure, transform it into an automatic or implicit process (procedural knowledge). According to Loewen (2015), Skill Acquisition Theory “is not specific to language, and it proposes that developing communicative competence in an L2 may follow the same trajectory as learning other skills, such as playing a musical instrument or playing a sport.” (p. 21). In relation to SLA and WCF, Polio (2012) has this to say:

The general idea is that there are three stages of development: declarative, procedural, and automatic. The first involves knowledge about a skill, the second smooth and rapid execution, and the third, faster execution, with less attention, and fewer errors. There is an important role for explicit knowledge, for the breaking apart of the skill into smaller units or steps, and for practice, a term explained in detail in DeKeyser (2007a). Feedback can provide explicit knowledge, help the learner focus on problem areas, and ensure that the wrong information is not proceduralized. Within this theory, being able to do something faster and with greater accuracy is evidence of learning and there is no reason that the theory should preclude performance on written production tasks. … Declarative knowledge, which can include explicit knowledge, plays a role within this theory and it must become proceduralized through practice. Feedback, in addition, is helpful so that one does not proceduralize inaccurate language, .... (p. 381)

As suggested above, WCF in the form of explicit knowledge, may go a long way when practiced adequately and effectively to enhance the automatization of linguistic knowledge. According to Ellis (2006), researchers do concur that the ultimate aim of L2 instruction is the acquisition of implicit knowledge but as explained by Polio above, explicit knowledge (of which WCF plays a role to achieve) may also lead to the development of implicit knowledge.

2.2.2 Sociocultural theory

Sociocultural theory is a more learner-centered approach that considers learning as an active process involving an interaction between the learner and his/her environment. Vygotsky is one of the key founders of this theory. To highlight the central role of social interactions in cognitive language development, Vygotsky (1978) advocated the view that mental functioning is intrinsically linked to the structures and processes of social practices, and undergoes transformations related to the internalization of these social processes. In regard to this conception of the nature of language development, Vygotsky introduced the concept of Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) to describe the distance between a learner’s current developmental state and his/her potential development. According to Brown (2007), this notion can be applied to learning in the foreign language context. The question then is how is WCF manifested in the socio-cultural theory of L2 acquisition? Polio (2012) is one of the few researchers who has tried to explain the relevance of sociocultural theory to WCF. Indeed, Polio considers that sociocultural theory is more related to writing than all other SLA theories:

Of all the approaches, the sociocultural approach could be said to be the most unequivocally related to writing. Even those who view speaking as an innate process

governed by rules of Universal Grammar cannot deny that writing is a learned, social process. (p. 382)

With respect to how error correction can be operationalized within the sociocultural theory to ensure second language acquisition, Aljaafreh and Lantolf (1994) state:

Effective error correction and language learning depend crucially on mediation provided by other individuals, who in consort with the learner dialogically co-construct a zone of proximal development in which feedback as regulation becomes relevant and can therefore be appropriated by learners to modify their interlanguage systems. From this stance, learning is not something an individual does alone, but is a collaborative endeavor necessarily involving other individuals. (p. 480)

In simpler terms and as presented above, a sociocultural theory of SLA encourages scaffolding of L2 learners. WCF practice by definition can be regarded as an activity that promotes scaffolding and may thus facilitate second language learning.

2.2.3 Interactionist perspective

According to Yoshida (2008), the focus on form perspective that emerged in the 1990s encouraged learners to pay attention to linguistic forms in communicative language classrooms. This resulted in more research in the corrective feedback domain which is perceived as a concept that draws students’ attention to the linguistic form of their productions. This idea of attention which was explored by Schmidt (1990) as the noticing hypothesis, affirms that learning a second language is a conscious process and therefore, requires attention. The noticing hypothesis is divided into three levels: perception, awareness and comprehension. First, perception is the conscious recording of signals from external events in order to create internal representations. Second, awareness is the perception of these stimuli and their storage in the long-term memory. Perception and awareness are considered essential in learning. This awareness takes place in the working memory. Finally, comprehension involves the comparison of perceived forms with the interlanguage in order to determine their similarities and differences. According to Schmidt, if the learners do not know the nature of the error, they will not be able to correct it and understand why they had to make the correction. They will most likely make the same mistakes in their subsequent essays since they will not have perceived the gap between their interlanguage and the appropriate form. The WCF process will therefore play a role in helping learners perceive,

take note and understand their errors. An interaction between the learner and anyone who has knowledge of the correct form would have to occur for learning to be achieved.

In addition, Long (1996), one of the major proponents of the interactionist perspective, suggested that the student’s attention must be drawn to the formal aspects of the language and interaction would help to successfully achieve that. According to him, input would be more comprehensible when there is an interaction between the teacher and the learner in the L2 class. As such, one can say that WCF may take place during interaction between teachers and their learners or between learners and a more capable peer. Teachers can make corrections when they encounter language errors produced by their L2 students. This plays a key role in the acquisition of the language by drawing students’ attention to their faulty productions. Drawing the attention of learners to their written errors may serve as a starting point to enable them to acquire new knowledge or revise previous knowledge. The interactionist framework has been extensively used within research (Doughty & Williams, 1998; Ellis, 2001; Lyster & Ranta, 1997; Varonis & Gass, 1985)

2.3 Written corrective feedback techniques

Russell and Spada (2006) define WCF as “any feedback provided to a learner, from any source that contains evidence of learner error of language form. It may be oral or written [paper format or through an online platform], implicit or explicit” (p. 134). The intention of most teachers, when they provide WCF is to improve the accuracy of their students’ writing. Written corrective feedback as part of the revision stage of writing is intended to improve the linguistic accuracy of L2 learners and various studies have found it to be of some help to the students (e.g. Bitchener & Ferris, 2012; Li, 2010). It is mostly welcomed as an educational practice by both students and teachers. Various techniques are employed when teachers provide feedback to students.

Some researchers have defined and described these feedback types and strategies (Bitchener & Knoch, 2010; Ellis, 2009; Ferris, 2006). In discussing whether error feedback helps student writers, Ferris (2006) distinguished two types of feedback – direct and indirect. She defines direct feedback as “the provision of the correct linguistic form by the teacher to the student” (p. 83) whereas indirect feedback “occurs when the teacher indicates in some way that an error has been made – by means of an underline, circle, code or other mark” (p.

83). For Bitchener and Knoch, the indirect style makes students responsible for finding out the correct answer to the error to which their attention has been drawn.

A typology by Ellis (2009), which serves as a basis for a systematic approach to researching the effects of WCF, distinguishes two options: first, strategies for providing feedback and second, the students’ response to feedback. His typology concentrates on the correction of linguistic errors. He outlines and describes six strategies that teachers use in correcting these linguistic errors in students’ writing. As illustrated in Table 2.1, the first three strategies – direct, indirect and metalinguistic – are specific to the types of feedback mostly provided by teachers. Ellis further discusses the usefulness of each of these strategies. He indicates that direct feedback is mostly preferred by learners who might not be capable of correcting the error themselves; therefore, it is highly recommended for learners of a low proficiency level. He cites Lalande (1982) and Ferris and Roberts (2001) to argue that indirect feedback on the other hand encourages “guided learning and problem solving” which results in long-term learning. The fourth strategy (focus of feedback) refers to whether or not the teacher corrects all (or most) of the errors or does so more selectively. Second, if the teacher selects some, one would want to know which ones he or she selects or focuses more on. The fifth strategy, electronic feedback, is when links to a specific linguistic error are provided in a digital manner. Finally, reformulation (a very common strategy in oral corrective feedback) is one of the strategies where the students’ ideas are maintained but reconstructed in a native-like manner.

2.4 Conclusion

This chapter reviewed notions and the definitions of key terms pertaining to WCF and SLA theories. Although WCF does not subscribe to one particular theory, it serves as practice that can contribute to second language acquisition for the theories discussed. In the next chapter, a review of the most relevant research studies related to WCF preferences will be discussed.

Table 2.1: Ellis’ (2009) taxonomy of corrective feedback

Type of CF Description Studies

A. Strategies for providing CF

1. Direct CF The teacher provides the student with the correct form.

e.g. Lalande (1982) and Robb et al. (1986).

2. Indirect CF

a. Indicating + locating the error

b. Indication only

The teacher indicates that an error exists but does not provide the correction. This takes the form of underlining and use of cursors to show omissions in the student’s text.

This takes the form of an indication in the margin that an error or errors have taken place in a line of text.

Various studies have employed indirect correction of this kind (e.g. Ferris and Roberts 2001; Chandler 2003).

Fewer studies have employed this method (e.g. Robb et al. 1986). 3. Metalinguistic CF

a. Use of error code

b. Brief grammatical descriptions

The teacher provides some kind of metalinguistic clue as to the nature of the error.

Teacher writes codes in the margin (e.g. ww = wrong word; art = article). effects of using error codes

Teacher numbers errors in text and writes a grammatical description for each numbered error at the bottom of the text.

Various studies have examined the effects of using error codes (e.g. Lalande 1982; Ferris and Roberts 2001; Chandler 2003). Sheen (2007) compared the effects of direct CF and direct CF + metalinguistic CF.

4. The focus of the feedback

a. Unfocused CF b. Focused CF

This concerns whether the teacher attempts to correct all (or most) of the students’ errors or selects one or two specific types of errors to correct. This distinction can be applied to each of the above options. Unfocused CF is extensive.

Focused CF is intensive.

Most studies have investigated unfocused CF (e.g. Chandler 2003; Ferris 2006). Sheen (2007), drawing on traditions in SLA studies of CF, investigated focused CF.

5. Electronic feedback The teacher indicates an error and

provides a hyperlink to a concordance file that provides examples of correct usage.

Milton (2006).

6. Reformulation This consists of a native speaker’s reworking of the students’ entire text to make the language seem as native-like as possible while keeping the content of the original intact.

Sachs and Polio (2007) compared the effects of direct correction and reformulation on students’ revisions of their text.

LITERATURE REVIEW

3.0 IntroductionThis chapter reviews previous studies about WCF preferences in second language acquisition. It will start by first discussing studies that are most relevant to our research objective and then discuss how context plays a role in the preference and provision of WCF.

3.1 Written corrective feedback preferences in second/foreign language learning WCF is a very broad area of research in language studies. Studies in this area have involved its effectiveness (Li, 2010), the techniques of correction and the design of WCF (Bitchener & Ferris, 2012; Brown, 2012) and recently, the corrective feedback process via online platforms (Alvarez, Espasa & Guasch, 2012). The focus of this research is to explore the effectiveness aspect of WCF by examining the preferences and perceptions of students and teachers of French as a foreign language. The review of literature will thus be limited to those studies that have specifically explored WCF preferences. This review will be further largely limited to studies involving foreign language contexts.

A number of researchers have studied the notion of preferences in feedback with most of them exploring the perceptions of and reactions of students to feedback provided by teachers (Alshahrani & Storch, 2014; Amrhein & Nassaji, 2010; Hamouda, 2011; Lee, 2008). Among the studies that have investigated the feedback preferences, Hamouda (2011) examined 200 students’ and 20 teachers’ preferences and attitudes towards correction of classroom written errors in a Saudi EFL context. The student participants were native Arabic speakers of two classes in a Preparatory Year Program at the university level in the Effective Academic Writing course. The aims of the study were to find out the students’ and teachers’ preferences regarding written error corrections, the difficulties of the teachers in providing feedback, and the students’ difficulties in revising the papers after receiving their teacher’s written feedback. After analysing questionnaire responses from both teachers and students, the author found that students and teachers shared certain similar WCF preferences such as for feedback involving providing the correct form of the error (direct feedback) and focusing on grammatical, spelling and vocabulary errors. However, differences also emerged in terms

of the amount of feedback preferred. For example, most students preferred correction of all errors while teachers did not see that as feasible due to lack of time to do so.

A study conducted by Alshahrani and Storch (2014) examined how teachers’ WCF practices align with the institutional guidelines and their beliefs regarding the most effective forms of WCF as well as what their students prefer. This study was conducted with three teachers and their respective classes in an English language course in a Saudi Arabian university. The EFL writing class which focused on grammatical accuracy, vocabulary and the production of a well-structured essay, was designed to help students achieve an intermediate level of proficiency in English. Data were collected from 45 students’ written draft essays with their teachers’ feedback, teacher interviews and students’ responses to a questionnaire about their preferences. At this university, the institutional guidelines stipulated that WCF should be comprehensive and indirect. As reported in the study, teachers adhered to the institutional guidelines. In line with these guidelines, teachers provided comprehensive feedback which, as it turned out, was also the most preferred form of feedback by the students. However, with respect to indirect feedback, although this was the type provided by teachers, students preferred direct feedback, stating that it helped them get immediate correction and as such they were certain of the correct answer. Also, although students preferred a focus on grammar correction, the teachers’ focus was more on mechanics. To explain their preference, the teachers cited time constraints. Overall, the study showed that students’ preferences for WCF strategies could be similar or different when compared to those of their teachers. However, it should be noted that this study was conducted in a context where teachers’ feedback strategies were prescribed by the institution. Lee (2008) investigated the reactions of students to feedback in two Hong Kong secondary school classes with a focus on factors that might have influenced their reactions. Lee described feedback as a ‘social act’ and believed investigating the reactions of students to feedback would help build a better relationship between teachers and students in terms of feedback provision. First, the study investigated the nature of feedback provided by the two teachers in the study. To do so, the teachers’ focus on written feedback (feedback on errors and comments on content, accuracy, organisation, etc.) was quantified. The strategies used in providing feedback on the errors were also described to indicate how detailed they were. The teachers were also interviewed on what influenced their choice of strategy in providing

feedback. Second, the reactions of students to their teacher’s feedback was also investigated. The questionnaire administered to the students included what they preferred to get from the teacher as feedback. Third, a qualitative analysis was carried out to discuss the possible factors that affected students’ reactions to teacher feedback. The characteristics of feedback provided by both teachers were calculated respectively. Of a total of 962 feedback points collected from 40 student texts as corrected by one of the teachers (Teacher A), the results showed 75.8% of the feedback focused on language form and the rest (about 24%) pertained to comments relating mostly to content and language use. By contrast, in the case of the other teacher (Teacher B), about 98% of his feedback was form focused. Teacher B rarely made comments to other aspects of the students’ writing. Interviews conducted with the teachers to find out why they corrected the way they did showed that they were both acting based on the school’s policy which required teachers to mark student writing in detail and respond to every single error made.

A study conducted by Chen et al. (2016) examined the perceptions and preferences of 64 intermediate, advanced-intermediate and advanced learners in an EFL setting in China. The study was conducted in the English department of a public university where students in the first two years were taught in both Mandarin and English and the upper level students (third and fourth year) were taught in English only. The researchers questioned the students about their general perception of grammar instruction, their preferences for the amount and type of WCF as well as the types of errors they preferred to receive corrections on and why. The majority of the students irrespective of their proficiency level regarded grammar instruction as very important although most of them did not like studying it for reasons which the study did not investigate. Most of the students also indicated that error correction was important because it provided them with the opportunity to identify recurrent errors and it helped improve their writing. Correction of vocabulary errors was the least preferred compared to organizational errors (preferred by 42 out of 64 participants). In terms of the amount of feedback, most students preferred that teachers corrected only errors that interfered with the communication of ideas. A number of the students also preferred the correction of all or major errors. The findings about grammar instruction, types of errors and amount of WCF did not differ significantly according to proficiency level but such was not the case for the error correction techniques. The students’ most preferred technique was locating the error

and also indicating the type of error. However, a statistically significant difference was found among students at different proficiency levels; the 3rd-year students’ (the advanced level learners) appreciation of this type of technique was lower than that of the beginner and intermediate student groups. In addition, the findings showed that most of the students, when they received feedback, would read and correct all the errors. With a description of the institutional setting and an analysis by proficiency level, the study highlighted how some contextual factors may or may not impact students’ perceptions and preferences of WCF. One related issue with research on student and teacher WCF preferences is whether the reasons for these preferences are also explored. One of the few studies which explored the reasons behind student and teacher preferences for WCF is Amrhein and Nassaji (2010). The purpose of their study was to examine and compare the opinions and preferences concerning the WCF of English as a second language (ESL) upper-intermediate students and their teachers. Data were collected from 33 adult ESL students and 31 ESL teachers from five different English language classes at two different private English language schools in Victoria, B.C., Canada. In terms of the amount of WCF, the majority of students (93.9%), but less than half the teachers (45.2%), were of the view that all errors should be marked. When questioned about their reasons for this preference, students explained that they perceived WCF as a learning tool and thus preferred detailed, comprehensive feedback. By contrast, teachers indicated that the amount and type of feedback they gave was dependent on the effort and time required to do so. With regards to the types of WCF, both students and teachers stated that they mainly preferred clues or directions on how to fix an error because when students self-corrected, they more easily remembered their errors. However, the students and teachers differed with respect to their opinions as to the types of error that should be mostly corrected. Students showed stronger opinions about the correction of grammatical errors, punctuation errors, spelling errors, and vocabulary errors while teachers believed that the main focus should be on the comprehensibility of content. According to the authors, this difference of opinion when not discussed by students and teachers may cause student discontent and make error correction ineffective.

3.2 Influence of contextual factors on written corrective feedback preferences in second/foreign language learning

According to Evans et al (2010), it is not enough to simply ask students whether they want feedback or not, or what kind of feedback they want. They suggest that the emphasis should also be on how to help students write more accurately in their “unique learning contexts” (p. 446). Discussing contextual factors, the authors suggest that WCF research and pedagogy should consider the examination of additional variables which they group into three categories: learner, situational and instructional variables. They refer to learner variables as such factors as “first language (L1), nationality, cultural identity, learning style, values, attitudes, beliefs, socioeconomic background, motivations, future goals” (p. 448). These factors contribute to differentiating successful or unsuccessful individual learners of a second language (see Dörnyei, 2005; Guénette, 2007). Situational variables refer to “factors such as the teacher, the physical environment, the learning atmosphere, or even political and economic conditions” (p. 450). The instructional variable was referred to as “the different instructional methodologies used to facilitate learning which includes what is taught and how it is taught” (p. 450). The point therefore is that, when studies take into consideration these variables, the validity of results about language pedagogy may increase. Two studies, Elwood and Bode (2014) and Chung (2015), explored certain contextual variables when they examined WCF preferences in L2 learning.

Elwood and Bode (2014), in a study conducted with 410 university EFL writing students in Japan, investigated the mode of feedback preferred by students and what influenced their choices. The students were required to take a year-long academic writing course as first year students even though they had had six years of English education at the secondary school level. A questionnaire was developed to collect data about the type of feedback they desired, the type of errors they wanted feedback on and what they did with the feedback. Although the study did not compare students’ WCF preferences to that of teachers, it was found that the students strongly preferred direct and detailed feedback and did not appreciate when errors were simply marked without the provision of the correct form. They also preferred the use of the red pen to other pen colors as well as handwritten feedback to feedback given on electronic copies. Previous practices (the cultural background) in primary and secondary education in Japan, where teachers used red pens and provided detailed

handwritten feedback, may have influenced their choices. This study highlights contextual and individual factors that may influence the preference of students when it comes to the provision of feedback.

The role of context in students’ preference for WCF has also been explored by Chung (2015). Chung’s study investigated the type of WCF preferred by Korean EFL students and compared the results with two previous similar studies in the Japanese EFL (Ishii, 2011) and US ESL contexts (Leki, 1991). Data were collected using a survey questionnaire adapted from Leki (1991) and Ishii (2011). A total of 105 undergraduate university students in different departments took part in the survey. For the purpose of finding out the types of WCF the students preferred, items pertaining to six feedback types rated from very bad to very good were analysed. Based on the participants' responses to the questionnaire, the average frequency of responses for each of the six feedback types was calculated in order to find out the most and least preferred feedback types among Korean EFL learners. It was found that both Korean and Japanese EFL learners preferred direct feedback whereas the ESL students in the US mostly preferred the indirect method of feedback such as directing the student to a grammar handbook for an explanation or simply pointing out the error. 3.3 Conclusion to the literature review section

With respect to the present review of the literature, all studies of WCF preferences involved English as a second/foreign language (Alshahrani & Storch, 2014; Amrrhein & Nassaji, 2010; Chung, 2015; Elswood & Bode, 2014; Hamouda, 2011) learners. To my knowledge, no research has addressed students and teachers WCF preferences in the FFL context in general and more specifically, in the Ghanaian FFL context. The present study will be conducted in an FFL context in West Africa (Ghana) where learning French is regarded as important for regional integration (Nimako, 2014).

In addition, there has been little exploration of the reasons behind the WCF preferences of students and teachers. Some previous studies have compared the preferences but neglected an investigation into the reasons behind student and teacher preferences. To my knowledge, only Amrhein and Nassaji (2010) compared students’ reasons with those of teachers’. Based on their comparison of the reasons, Amrhein and Nassaji (2010) suggest

that teachers need to “openly discuss the use of WCF with students and ensure that students understand the purpose of WCF and shoulder responsibility for error correction” (p.116). They indicate that differences in preferences between teachers and students “could create some tension as well as challenges in error correction pedagogy” (p.116) and therefore recommend the need for further research in this area. As they point out, an understanding of students’ and teachers’ WCF preferences can serve as a stepping stone for designing effective feedback that will be student-teacher inclusive.

METHODOLOGY

4.0 IntroductionIn this chapter, I will describe in detail the methodology used to investigate the questions posed by this research. To do so, I first define the methodological approach and then present the context and the participants of the research. Following this, I outline the data collection instruments and the data collection procedures. Finally, I will explain how the data were analysed along with an overview of the ethical considerations.

4.1 Methodological approach

This research is a mixed method design that combines quantitative and qualitative methods to collect and analyse data with the aim of exploring the preferences of students and teachers with respect to written French in a non-francophone environment. According to Fortin and Gagnon (2016), mixed method research “has the advantage of allowing an integration of several perspectives and is particularly useful when the research question presents several facets where a single method would be inadequate for a sufficient exploration” (p. 246). For these reasons, this research uses quantitative methods (i.e., questionnaires with Likert-type responses) and qualitative methods (i.e., semi-structured interviews). The two methods complement each other. The semi-structured interviews allowed us to examine the contextual elements that influence students and teachers’ preferences and practice of written corrective feedback in more detail than the questionnaire. This helps to ensure a better triangulation of the data. Triangulation as defined by Gass and Mackey (2005) is “the use of multiple, independent methods in obtaining data in a single investigation” (p. 181). One concern of this study is to explore the reasons or factors behind the preferences of the participants – a gap observed in previous research on L2 learners’ feedback preferences. Using questionnaires may not provide a complete picture of what the participants’ preferences entail. To overcome this possible shortcoming, interviews were also conducted for the purposes of triangulation.

4.2 Context of the study

The study was conducted with students and teachers from the Department of French of the University of Cape Coast (UCC), Ghana. UCC is a public university situated in the central region of Ghana with about 14,000 regular undergraduate students (UCC, 2017). The Department of French is responsible for the teaching and learning of the French language. The Department offers both undergraduate and graduate programs in French studies. French as a Foreign Language (FFL) at the undergraduate level is taught in the Department over a four-year period (from level 100 to 400). The students admitted to the French program are normally students who have previously studied and passed a French oral and written expression exam at the secondary school level. Once the students are admitted to the program of French language, they must pass all the compulsory courses at the first and second year levels. It is then up to the student to decide whether to continue studying it until the final year or drop it after the second year. French is mainly the language of instruction in the department. The curriculum for the first two years of studies mainly involves grammar, oral expression, essay writing, an introduction to French linguistics, translation and French literature. Since my research concerns written feedback, it was carried out in the Written Expression class, a compulsory course for all first and second year students of the Department. A written course outline (see Appendix A) for the Written Expression course was obtained from the Department. The same course outline was used by all the five teacher participants.

4.3 Participants

The participants involved were Ghanaian university level students studying French as a Foreign Language (FFL) and their teachers. The participants were chosen by convenience. According to Fortin and Gagnon (2016), convenience sampling means an unrandomized choice of subjects who are accessible at a particular place and time. The data were collected from students registered in a level 200 class which focuses on essay writing (about half the time) as well as other language activities such as listening to audio recordings and discussions. At the level 200, approximately 140 students are registered in the targeted course each academic year. The course is a two-semester course (15 weeks per semester) and students meet during two weekly sessions, 1½ hours each. This group of students were

chosen because they have completed one year of the FFL program which also included a similar course involving essay writing and other language related activities. As such by the time the data was collected, the level 200 group of students had been involved in composing several essays and had received feedback from teachers on their essays. Data were collected from 107 level 200 students registered in the program as well as their teachers (5). The student group consisted of 28 males and 79 females aged between 18 and 33. The teachers were all males. The students were divided into 5 groups by the Department and each group had its own teacher.

4.4 Data collection instruments

For this research, two survey questionnaires – one for students, the other for teachers - adapted from two studies (Amrhein & Nassaji, 2010; Chen et al., 2016) were used. In addition, interviews with all the teacher participants and student volunteers (9 students) were conducted to further explore the possible reasons and the contextual factors that may influence their WCF preferences.

4.4.1 Questionnaire design

The questionnaires were designed to elicit both quantitative and qualitative data. The questions focussed on collecting data related to the first four research questions, i.e., grammar instruction; the amount, focus and type of WCF strategies; and the use of written feedback. The questionnaire contained both closed questions requiring Likert-type responses as well as open-ended questions that allowed teachers and students to express the reasons behind their preferred WCF strategies. Both questionnaires (students and teachers) are parallel in structure; questions asked in the student questionnaire were repeated in the teacher questionnaire with changes only to suit the function of the teachers. At the beginning of the questionnaire, students and teachers were asked to indicate background information about their sex, age, previous FFL studies (students only), and years of experience in teaching written expression (teachers only). The second part of the questionnaire contained questions about the participants’ preferences in terms of grammar instruction, the amount of WCF, focus of WCF and type of WCF strategies as well as the use of WCF. For the student questionnaire, see Appendix B, and for the teacher’s, Appendix C. Based on previous questionnaires similar to this type and as piloted with two students (non-participants but

French as a Second Language students), student participants were given 30 minutes to complete the questionnaires. The questionnaire was in English and type written and printed for the respondents. The questionnaires were distributed to the participants at the university by the researcher.

4.4.2 Interview

As previously pointed out in the literature review, the reasons and contextual factors underlying students and teachers’ WCF choices were not investigated by most studies. For the few which did (Amrhein & Nassaji, 2010; Chen et al., 2016), the reasons were deduced from responses to open-ended questions found on written questionnaires. In order to get more information about the preferences, this study used interviews in addition to open-ended questions on questionnaires. Interviews thus allowed the researcher to obtain more in-depth information because they gave greater freedom to the participants to express their beliefs and preferences in their own words, without having to choose predetermined answers as in the questionnaires. Consequently, they provided greater scope for understanding the phenomenon being investigated (Fortin & Gagnon, 2016). As well, the interviews in this study were used to provide information to confirm teacher and student preferences regarding the type and frequency of corrective feedback. To this end, the interview protocols were based on the student and teacher questionnaires and the research questions of the present research study. The student interview protocol (see Appendix D) was organised around two themes: their experience learning writing (including written feedback) and their motivation. That of the teachers (see Appendix E) was related to their experience teaching writing, their training with respect to how to teach writing, and the institutional practices pertaining to the administration of the Written Expression course. Students and teachers were invited on a voluntary based to take part in a semi-structured interview. As a means of validation, the interview protocol was piloted with two students in order to determine the possible duration and to observe the students’ understanding of the questions.

4.5 Data collection procedures

Before starting the data collection process, the research project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Université Laval. The data collection took place over a three-week period in November 2017 when students were almost at the end of the semester. Two months prior to this, letters for authorization and the notice of recruitment had been sent to the Head of Department for distribution. With the help of the teachers of the five groups, the consent forms were distributed to their classes one week prior to the administration of the questionnaires. All participants received an information sheet stating the purpose of the project, the data collection procedures, and the participants’ right to withdraw at any time. Questionnaires were administered to students by the researcher during regularly scheduled class periods to those students who consented to taking part in the study. The questionnaire administration took approximately 30 minutes. The role of the researcher was to ensure that all students understood the instructions and to collect all of the questionnaires once answered. In addition, a recruitment document was given to students to know whether they were willing to participate in the interview part of the research. Of the 23 students who volunteered for the interview, nine were recruited for the interviews based on the fact that they had indicated willingness to come to the interview with a corrected written essay. The interviews, which took approximately 30 minutes, were scheduled individually with the student volunteers and were conducted outside the classrooms in a separate office. The interviews with the five teacher participants were carried out in their respective offices and lasted approximately 25 minutes. All interviews were recorded and then transcribed by the researcher.

4.6 Data analysis

To analyze the data collected through the instruments used in this research, two types of analysis, namely, statistical analysis and content analysis were used. Prior to analyzing the collected data, the quantitative data of the questionnaire responses were organized in an Excel spreadsheet, then imported to the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), and discussed and analyzed with the help of the Math and Statistics Department of Université Laval. For the first part of both questionnaires (the demographic data), descriptive analysis was used to create a resume of the information provided. The frequency and mean values of responses for the quantitative data from the questionnaire for students as well as teachers were calculated and tabulated separately. Following this, tests were conducted to find out

whether the differences between student and teacher responses were statistically significant (research question 4). To compare the results of the survey between the students and the teachers, the following statistical procedures were used:

- for the Likert-scale questions, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) - for questions with a single choice of item, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) - for closed questions (Yes/No), a Chi-square test.

As explained by Mackey and Gass (2005), an analysis of variance (ANOVA) involves comparing the variance within each group (intragroup) with that between groups (intergroups). An ANOVA may have one or more factors. The statistics calculated in ANOVA is the F value. This expresses the ratio of intergroup variance to intragroup variance. To determine whether the value of F is significant, the results obtained are compared with the critical values of the distribution. The MANOVA, according to Tabachnick and Fidell (2012), uses the same conceptual framework as the ANOVA. It is an extension of the ANOVA which allows to consider a combination of dependent variables rather than a single dependent variable. The advantage of using a MANOVA instead of several simultaneous ANOVA lies in the fact that it takes into account the correlations between the variables responses and thus allows a better use of the information from the data. The MANOVA tests the effects of factors on several answers of the variables. With a MANOVA, it is possible, therefore, to test jointly all the hypotheses tested by a series of ANOVAs with more chance of observing a significant effect. Thus, we used the MANOVA to test jointly the items of a given category (research questions 1, 5 and 6 of the questionnaire). However, to make comparisons between teachers and students, item-by-item of each category of the Likert-scale questions, we used the results of the ANOVA. For the Yes/No questions, we used the Chi-square test. The Chi-square test is “a non-parametric inferential statistical analysis used to compare a set of data representing frequencies, percentages and proportions” (Fortin & Gagnon, 2016, p. 432).

Qualitative data taken from the teacher and student questionnaire as well as the interviews were compiled and categorized based on emergent themes in reference to the research questions (Fortin & Gagnon, 2016). The qualitative data were used for the purpose of triangulation and examination of the contextual factors. Table 4.1 provides an overview of each research question, the source of data and the mode of analysis.

Table 4.1: Overview of research questions, data collection instruments and mode of analysis. RESEARCH QUESTIONS DATA COLLECTION INSTRUMENTS ANALYSIS 1. How do FFL students and teachers at tertiary level in Ghana view the role of

grammar

instruction in their writing classes?

Student questionnaire : - statements with a Likert scale response format

Teacher questionnaire : - statements with a Likert scale response format

- Responses were recorded on an Excel spreadsheet and imported to SPSS.

- Mean ratings of responses were calculated

2.What do FFL students and teachers think is most useful and why, with respect to a. amount of WFC b. types of WCF c. types of errors to be corrected Student questionnaire: -Statements with a Likert scale response format or choice of answers

- Yes/No questions - Open-ended questions to elicit reasons for their preferences

Teacher questionnaire: - Statements with a Likert scale response format or choice of answers

- Yes/No questions

- Open-ended questions to elicit reasons for their preferences.

Quantitative data

- Responses were recorded on an Excel spreadsheet and imported to SPSS.

- Mean ratings of responses were calculated

- Frequency of responses were tallied for the Yes/No questions

Qualitative data (Open-ended questions)

- Responses were compiled and categorized in

function of the question.

3. What do students prefer to do with the WCF feedback they receive and what do teachers think they should do with it?

Student questionnaire: - Statements with choice of responses.

Teacher questionnaire: - Statements with choice of responses.

- Frequency of responses were tallied.