Title: Associations of lifetime traumatic experience with dysfunctional eating patterns and post-surgery weight-loss in adults with obesity: a retrospective study

Running title: Trauma exposure and bariatric surgery outcomes 1

2 3 4 5

Abstract

This study aimed to examine the associations of lifetime traumatic experience with pre- and post-surgery eating pathology and postoperative weight-loss in a sample of bariatric surgery patients using electronic medical record (EMR) data. Pre-surgery lifetime exposure to traumatic event, pre- and post-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns, and post-operative total and excess weight losses were extracted from EMR of 200 bariatric surgery patients in 2013 and 2014. Logistic regression analyses were conducted. 60.5% of the patients (81.5% women; age=44.4±11.5 years; BMIpre=44.9±5.5 kg/m2) reported that they were exposed to a traumatic event during their lifetime. Before surgery, trauma exposure was associated with impulsive, compulsive or restrictive eating patterns (OR=2.40), overeating or disturbed eating (OR=1.55), and grazing or night eating behaviors (OR=1.72). After surgery, trauma exposure was associated with lower total weight loss at 6 months (OR=2.06) and 24 months (OR=2.06), and to overeating or disturbed eating (OR=1.53) 12 months after surgery. Bariatric surgery candidates with a history of trauma exposure could benefit from closer medical, dietetic, and/or psychological follow-up care to avoid insufficient postoperative weight loss as well as reappearance of dysfunctional eating patterns after

6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

Introduction

Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in individuals with obesity is higher than in individuals with normal weight (Husky, Mazure, Ruffault, Flahault, & Kovess-Masfety, 2017; Scott et al., 2008). A meta-analytic review of 68 articles (n=115,545) concluded that the prevalence of mental disorders of adults with obesity is 23% for mood disorders, 17% for binge eating disorder, 12% for anxiety disorders, and 9% for suicidal ideation (Abilés et al., 2010; Dawes et al., 2016; Simon et al., 2006). We know that lifetime traumatic experiences such as physical, sexual and emotional abuse or neglect are risk factors leading to such mental health conditions (Brewerton, 2007). Indeed, adults with extreme levels of obesity are more likely to have experienced lifetime traumatic events than individuals with a BMI below 40 kg/m2 (Brewerton, O’Neil, Dansky, & Kilpatrick, 2015).

Additionally, early and late exposure to life adverse experiences, such as traumatic experiences, has been associated with adult obesity in men and women (Alvarez, Pavao, Baumrind, & Kimerling, 2007; Grilo et al., 2005; Gunstad et al., 2006; Thomas, Hypponen, & Power, 2008). A 30-year follow-up prospective study showed that children with a history of trauma are at risk of developing adult severe obesity (Bentley & Widom, 2009). The impact of lifetime traumatic experience on weight gain could be explained by increased risks of being diagnosed with eating, mood, and anxiety disorders (Gustafson & Sarwer, 2004; Palmisano, Innamorati, & Vanderlinden, 2016), as well as psychological dysfunction (D’Argenio et al., 2009). These results suggest that individuals with excess weight tend to cope with their traumatic experiences by eating. In fact, previous investigations showed that the impact of traumatic experience on emotional eating (i.e., eating to regulate emotions) was moderated by emotion regulation (i.e., ways of regulating emotions in a range of situations) and psychological distress (Burns, Fischer, Jackson, & Harding, 2012; Michopoulos et al., 2015; Moulton, Newman, Power, Swanson, & Day, 2015).

22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46

Bariatric surgery has widely been accepted as a reference in the treatment of severe obesity and proven as the most effective treatment in individuals with morbid obesity (Fried et al., 2013). However, previous evidence showed that patients experiencing stressful life events and having stressful lifestyles are more likely to lose less weight after weight-loss treatments (Adams, Salhab, Hussain, Miller, & Leveson, 2013; Elfhag & Rössner, 2005).

There is evidence suggesting that comorbid chronic psychiatric conditions may lead to lower weight-loss after bariatric surgery mainly because of poor tolerance to surgically induced food limitations and increased likelihood of having difficulties complying with medical and dietary recommendations (Guisado, Vaz, López-Ibor Jr, & Rubio, 2001; Kinzl et al., 2006; Van Hout, Verschure, & Van Heck, 2005; Wimmelmann, Dela, & Mortensen, 2014). Furthermore, pre-surgery binge eating disorder (Beck, Mehlsen, & Støving, 2012; Bocchieri-Ricciardi et al., 2006), emotional eating (Canetti, Berry, & Elizur, 2009) and other dysfunctional eating patterns (e.g., overeating, grazing) have been shown to be negative predictors of weight-loss following bariatric surgery (Adams et al., 2013; Herpertz, Kielmann, Wolf, Hebebrand, & Senf, 2004; Meany, Conceição, & Mitchell, 2014; Robinson et al., 2014; Van Hout et al., 2005; Wimmelmann et al., 2014; Wood & Ogden, 2012). However, conflicting results showed that pre-operative binge eating disorder could be associated with greater post-surgery weight-loss (Kinzl et al., 2006; Livhits et al., 2012), and that pre-surgery psychological distress, except for severe chronic psychiatric disorders, could be associated to greater post-surgery weight-loss (Herpertz et al., 2004).

On the other hand, several reviews showed that bariatric surgery could improve mental health and psycho-social functioning (Herpertz et al., 2003, 2004; Kubik, Gill, Laffin, & Karmali, 2013; Pataky, Carrard, & Golay, 2011; Sarwer, Wadden, & Fabricatore, 2005), as well as eating patterns of individuals with obesity (Bocchieri-Ricciardi et al., 2006; Kubik et al., 2013; Pataky et al., 2011; Sarwer et al., 2005). The Swedish Obese Subjects (Karlsson, 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71

Sjöström, & Sullivan, 1998) study results showed that symptoms of depression and anxiety decreased and that health-related quality of life improved 1 year after bariatric surgery; and other studies showed that depression symptoms decreased up to 4 years post-surgery (Dixon, Dixon, & O’Brien, 2003). By contrast, a study of 196 bariatric surgery patients showed that a combination of pre-operative mood and eating disorders decreased the likelihood of following behavioral guidelines and treatment compliance 6 months after surgery in the USA (Gorin & Raftopoulos, 2009), and Kinzl and colleagues (Kinzl et al., 2006) in a 30-month follow-up study among 140 patients showed that women undergoing bariatric surgery reporting an adverse childhood experience tend to lose less weight than those without these experiences in Austria. These conflicting results could explain the lack of consensus on the effects of pre-surgery psychological distress and dysfunctional eating patterns on bariatric pre-surgery weight and eating outcomes, and highlight the need for further specific investigations in different countries while health care policies differ. Moreover, authors (Kinzl et al., 2006) showed that (a) a combination of absence of pre-operative psychiatric disorder, presence of dysfunctional eating patterns before surgery and positive childhood experience are associated with greater weight-loss at least 30 months after surgery and that (b) a combination of presence of multiple psychiatric disorders before surgery, absence of pre-operative dysfunctional eating patterns and presence of adverse childhood experience are associated with lower weight-loss at least 30 months after surgery.

In summary, lifetime exposure to traumatic events appears to lead to mental health conditions, eating pathologies, and obesity. However, there are conflicting results regarding the associations of traumatic experience with bariatric surgery outcomes, which could be explained by differences in national health care policies. Moreover, available studies focused on childhood adverse events and did not assess weight-loss and eating behaviors conjointly after surgery. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the associations of childhood and 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96

adulthood traumatic experience with pre- and post-surgery eating pathology and weight-loss in a sample of bariatric surgery patients using electronic medical record (EMR) data in France.

Materials and methods Sample

A retrospective chart review was conducted for candidates consecutively admitted for bariatric surgery at the Nutrition Department of Ambroise Paré Hospital (Boulogne-Billancourt, France), starting from early 2013 to late 2014 (2-year period). A total of 301 patients were screened for EMR eligibility, from which 41 were excluded, resulting in 260 EMR screened for eligibility. Inclusion criteria were adults (aged between 18 and 70 years) with obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) who benefited from bariatric surgery (any). Exclusion criteria were: absence of pre-surgery psychological interview in EMR, absence of available 12-month follow-up data in EMR, pregnancy in the first 2 years after surgery, and aged over 70 years. A total of 200 unique cases were eligible for statistical analysis. Figure 1 displays the flow chart of participation. Data were collected in an electronic database registered with the French national data protection agency (Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté, 1824098). Informed consent to anonymously analyze participants' data for research purposes has been collected from the patients before surgery.

Procedures

Pre-surgical care in the Nutrition Department included grouped psychoeducational components for individuals with obesity (e.g., diet, exercise, psychological processes, medical care) as well as individual interviews with nutritionists, dieticians, physical activity educators, and psychologists. Information regarding energy balance, medical comorbidities, dietetic, physical activity, psychological distress, and eating behaviors were provided to the patients. Pre- and post-surgical care in the Nutrition Department followed national guidelines from the 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121

French Authority for Health (Haute Autorité de Santé, 2011), which are in line with the European guidelines (Fried et al., 2013). The indication for bariatric surgery was approved by a multidisciplinary team in accordance with French guidelines for bariatric surgery, which are similar to those of the US National Institutes of Health (Haute Autorité de Santé, 2009; National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity, 2000). The type of procedure (e.g., laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) was chosen during the multidisciplinary meeting, considering the patient's medical summary and patient's preference.

Data collection

Pre- and post-surgery nutritional interviews were led by clinical nutritionists from the same clinical staff working in accordance with the national standards (Haute Autorité de Santé, 2009, 2011). Patients were systematically weighed and heighted in order to estimate BMI. Moreover, dysfunctional eating patterns were identified through either clinical interviews or 7-day pen-and-paper diaries. A list of seven dysfunctional eating patterns is available in EMR, the clinical nutritionist had to tick the corresponding boxes. Thus, impulsive eating, compulsive eating, restrictive eating, and night eating syndrome were identified through clinical interviews; and overeating, disturbed eating, and grazing were identified through diaries.

Pre-surgery psychological semi-structured interview aimed at identifying psychological contra-indications for bariatric surgery such as intellectual disability, psychotic disorder, obesity-related anxiety or mood disorder and weight-related eating disorder (Fried et al., 2013). These interviews were led by the very same psychologist (DT) lasting 90 minutes on average and following the same structured template: socio-demographic information, personal history and psychiatric information, potential traumatic experiences, weight history, social support for bariatric surgery, and personal motives for bariatric surgery.

122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146

Data extraction

Data were extracted from EMR and coded in a database by the same investigator (co-first author, FV). Lifetime traumatic experience was (co-first quoted as presence or absence of any life adverse event reported during pre-surgery psychological interview, and then indexed in terms of exposure to either dysfunctional family background (e.g., parental divorce, educational neglect), emotional abuse or neglect (e.g., bullying, verbal abuse), physical or sexual abuse or neglect (e.g., assault, rape), or early experience of separation or loss (e.g., loss of a parent in early childhood). This categorization has been used in previous investigations (D’Argenio et al., 2009; Grilo et al., 2005; Kinzl et al., 2006).

Dysfunctional eating patterns were identified in EMR among a list of seven: impulsive eating, compulsive eating, restrictive eating, overeating, disturbed eating, grazing, and night eating syndrome. These eating patterns were scored dichotomously (present vs. absent) and indexed into 3 categories for the purpose of this study as (a) impulsive, compulsive or restrictive eating, (b) overeating and disturbed eating, and (c) atypical eating patterns such as grazing (including snacking) and night eating syndrome. This categorization into 3 subsets of eating patterns has been adapted from previous investigations in bariatric surgery patients (Kinzl et al., 2006). This categorization can be explained as follow: (a) impulsive, compulsive and restrictive eating patterns are conceptualized as psychological processes leading to eating disorders such as binge eating or bulimia, (b) overeating and disturbed eating are conceptualized as showing difficulties in following dietary guidelines and recommendations from national health authorities for patients undergoing bariatric surgery, and (c) atypical eating patterns are conceptualized as habits such as snacking between meals during the day or at night. Data analyses 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170

The deterministic nearest neighbor hot deck imputation was used to address missing values of pre-and post-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns. This procedure allows imputing the data of a patient, without missing data, who has the same socio-demographic or medical baseline characteristics as a patient with missing data (Andridge & Little, 2010). Eight variables were used to impute pre-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns (gender, age at surgery [± 5 years], socio-professional status, surgical procedure, traumatic experience, obesogenic family background, marital status, and maximal BMI [± 5 kg/m2]), and nine variables were used to impute post-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns (adding pre-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns). This procedure has been performed by an epidemiologist blind to study objectives.

To assess the variations in body weight, percentage of total weight loss (%TWL = (initial BMI – nadir BMI) / (initial BMI) × 100) was calculated (van de Laar, 2012). Socio-professional category was categorized into three classes: entrepreneurs and non-manual employees at higher and intermediate level, assistant non-manual employees and manual workers, and inactive (retired and unemployed). As weight loss outcomes were skewed in our sample (skewness / SE > 1.96), TWL has been dichotomized using the median value. Dichotomizing skewed continuous variables has previously been suggested as a way to manage non-normality (MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002). Additionally, instead of defining arbitrary cut-offs for TWL (e.g., 30% of TWL as a criterion of success), we used the median at each time (i.e., pre-surgery, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months post-surgery) to dichotomize TWL. Using an arbitrary cut-off might not be adapted to the patients included in this monocentric study when considering possible differences in pre- and post-surgery care as well as possible differences in procedures for performing the same surgical technique.

First, weighted frequency of presence or absence of lifetime traumatic experience were examined by socio-demographic, medical, and surgical variables, as well as eating patterns; 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195

and Chi-squared (for categorical variables) and Student’s t (for continuous variables) tests were performed to determine between-group differences on pre-surgery variables. A p-value below 5% was considered as significant. Second, logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine whether the presence of lifetime traumatic experience was associated with post-surgery lower TWL and dysfunctional eating patterns at pre- and post-post-surgery; and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were computed. All analyses were performed using R (R Core Team, 2013).

Results Missing data and sample characteristics

A total of 29 EMR (93% women, mean age: 43.5 years) had missing values for pre- or post-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns. The patients from whom data were imputed to the patients with missing data were at 86% (range: 50–100%) in the same categories of socio-demographic and medical variables. Student's t-tests revealed that the sample of patients with missing values was not statistically different from the sample without missing values for weight-loss, dysfunctional eating patterns and traumatic experience.

Included patients were 81.5% women aged from 18 to 66 years (M=44.4, SD=11.5). The mean pre-surgery BMI was 44.9 kg/m2 (SD=5.5; range: 33.2–59.3), and patients benefited from Roux-en-Y gastric by-pass (54%), sleeve gastrectomy (37%), adjustable gastric band (1.5%) or a conversion (any, 12%). A large majority of patients already tried some form of diet before surgery (95%), and 27% had some kind of psychiatric disorder. A vast majority of patients (60.5%, n=121) reported that they experienced life adverse events during their lifetime (43% experienced early separation or loss, 31.4% experienced emotional abuse or neglect, 18.2% had dysfunctional family background, and 9.9% experienced physical or sexual abuse). The 60 excluded patients did not significantly differ from the 200 included patients on any of the pre-surgery variables.

196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220

Baseline characteristics are displayed by presence or absence of lifetime traumatic experience in Table 1. Overall, 18.5% of the sample belonged to the higher and intermediate socio-professional class (26.6% without any traumatic experience, 13.2% with a traumatic experience), 57% to the lower non-manual and manual working class (54.4% without any traumatic experience, 58.7% with a traumatic experience), and 24.5% were inactive (19.0% without any traumatic experience, 28.1% with a traumatic experience). This social distribution held significant differences (χ2=6.38, df=2, p=0.041).

Surgery weight and eating outcomes

Six months after surgery, mean patients' BMI was 33.2 kg/m2 (SD=5.1), resulting in a TWL of 22.8% (SD=5.9) of BMI. Twelve months after surgery, mean patients' BMI was 30.7 kg/m2 (SD=5.1), resulting in a TWL of 28.1% (SD=8.2) of BMI. Twenty-four months after surgery, mean patients' BMI was 30.3 kg/m2 (SD=5.3), resulting in a TWL of 29.9% (SD=8.7) of BMI. When considering the presence or absence of a traumatic experience, total loss of BMI as a continuous variable did not show any significant between group differences. Student's t tests revealed no significant differences according to the presence or absence of lifetime traumatic experience on pre-surgery BMI (p=0.791) and post-surgery TWL at 6 months (p=0.642), 12 months (p=0.805), and 24 months (p=0.269).

A total of 94.5% of participants had overeating or disturbed eating before surgery, and 50.5% kept these patterns 12 months after surgery. Thirty-four percent of participants had impulsive, compulsive or restrictive patterns of eating before surgery, while 2.5% still had these patterns 12 months after surgery. 49% of participants had atypical eating patterns (grazing and night eating syndrome) before surgery, and 12.5% kept these patterns after surgery. Chi-squared tests revealed no significant differences according to the presence or absence of lifetime traumatic experience in the distributions of impulsive, compulsive or restrictive patterns of eating (p=0.052), overeating or disturbed eating (p=0.922), and atypical 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245

eating patterns (p=0.523) at pre-surgery; and impulsive, compulsive or restrictive patterns of eating (p=0.627), overeating or disturbed eating (p=1.000), and atypical eating patterns (p=0.548) at post-surgery.

Associations between traumatic experience and weight outcomes

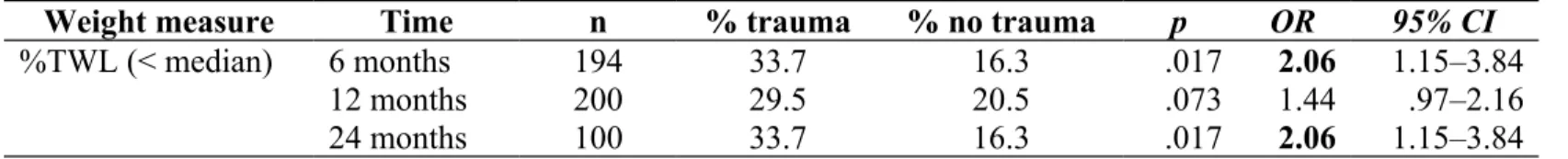

TWL at 6, 12, and 24 months are presented by presence or absence of lifetime traumatic experience in Table 2. Among participants who lost less total weight 6 months after surgery, 33.7% experienced a traumatic event during their lifetime and 16.3% did not (p=0.017). There is no significant difference in the distribution of participants for TWL 12 months after bariatric surgery between participants with and without lifetime traumatic experience (p=0.073). Among participants who lost less total weight 24 months after surgery, 33.7% reported they experienced a traumatic event and 16.3% did not (p=0.017). Figure 2 displays the proportion of total sample showing higher pre-surgery BMI and post-surgery lower TWL by presence or absence of any lifetime traumatic experience.

Experiencing a lifetime traumatic event has been associated to lower TWL (OR=2.06; 95%CI=1.15–3.84) 6 months after surgery, and lower TWL (OR=2.06; 95%CI=1.15–3.84) 24 months after surgery. No significant associations were found between lifetime traumatic experience and weight-loss 12 months after surgery (OR=1.44; 95%CI=0.97–2.16). Furthermore, despite significant associations between lifetime traumatic experience and socio-professional category (see Table 1), 2 (traumatic experience) × 3 (socio-professional category) analysis of variance revealed no significant effect of the interaction on pre-surgery BMI (p=0.620), as well as on post-surgery total weight-loss at 6 months (p=0.332), 12 months (p=0.670), and 24 months (p=0.431).

Associations between traumatic experience and eating outcomes

Pre- and post-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns are presented by presence or absence of lifetime traumatic experience in Table 3. Before surgery, 24% of participants with 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270

lifetime traumatic experience and 10% without any traumatic experience reported having impulsive, compulsive or restrictive eating patterns (p=0.001). Likewise, 57.5% of participants with lifetime traumatic experience and 37% without any traumatic experience reported having overeating or disturbed patterns of eating before surgery (p=0.003). Additionally, before surgery, 31% of participants with lifetime traumatic experience and 18% without any traumatic experience reported having grazing behavior or night eating syndrome (p=0.009). After surgery (12 months), 30.5% of participants with lifetime traumatic experience and 20% without any traumatic experience reported having overeating or disturbed patterns of eating (p=0.038). However, there is no difference between participants with and without lifetime traumatic experience according to impulsive, compulsive or restrictive eating patterns (p=0.657), as well as to grazing behavior or night eating syndrome (p=0.079) 12 months after bariatric surgery. Figure 3 displays the proportion of total sample having pre-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns by presence or absence of any lifetime traumatic experience, and figure 4 displays the proportion of total sample having dysfunctional eating patterns 12 months after bariatric surgery by presence or absence of any lifetime traumatic experience.

Experiencing any lifetime traumatic event has been associated with pre-surgery impulsive, compulsive or restrictive eating patterns (OR=2.40; 95%CI=1.45–4.13), overeating or disturbed patterns of eating behavior (OR=1.55; 95%CI=1.16–2.09), and grazing or night eating syndrome (OR=1.72; 95%CI=1.15–2.62). 12 months after surgery, lifetime traumatic experience was associated to overeating or disturbed patterns of eating behavior (OR=1.53; 95%CI=1.03–2.29). No significant associations were found between lifetime traumatic experience and neither post-surgery impulsive, compulsive or restrictive eating patterns (OR=1.53; 95%CI=0.09–4.02) nor post-surgery grazing or night eating syndrome (OR=1.53; 95%CI=0.95–5.21). Despite significant associations between lifetime traumatic experience 271 272 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288 289 290 291 292 293 294 295

and socio-professional category (see Table 1), 2 (traumatic experience) × 3 (socio-professional category) analysis of variance revealed no significant effect of the interaction on pre-surgery impulsive, compulsive or restrictive eating patterns (p=0.267), overeating or disturbed patterns of eating behavior (p=0.780), grazing or night eating syndrome (p=0.571), as well as on post-surgery impulsive, compulsive or restrictive eating patterns (p=0.234), overeating or disturbed patterns of eating behavior (p=0.410), grazing or night eating syndrome (p=0.571).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the associations of lifetime traumatic experience with pre- and post-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns and post-surgery weight-loss in a French sample of bariatric surgery patients. It was hypothesized that lifetime exposure to traumatic experience may be a prognostic factor in post-operative weight-loss in patients with obesity. The results of this retrospective chart review showed that bariatric surgery patients who reported a lifetime exposure to traumatic event are more likely to attend lower weight loss after surgery. Moreover, results showed that patients with lifetime exposure to traumatic experience are more likely to experience pre-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns from 3 categories (i.e., impulsive, compulsive and restrictive eating; overeating and disturbed eating; grazing and night eating syndrome), and to experience post-operative overeating and disturbed eating.

Before bariatric surgery, no difference was found between patients with and without any exposure to traumatic experience when considering pre-operative BMI. However, 6 and 24 months after surgery, patients who reported having experienced a traumatic event during their lifetime were significantly more likely to lose less weight than patients without exposure to any traumatic events. While trauma exposure is known to lead to psychiatric disorders (Brewerton, 2007), these differences in the associations between traumatic experience and 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320

weight loss may be explained by meeting more difficulties changing dysfunctional eating patterns when psychological distress is present (Gorin & Raftopoulos, 2009). Another explanation could be that women with obesity who were exposed to sexual abuse or violence use their excess weight as an 'adaptive' way to protect themselves against sexual assault (Gustafson & Sarwer, 2004; Wiederman, Sansone, & Sansone, 1999).

Consistent with previous investigations (Palmisano et al., 2016), the results of this study showed that patients who were exposed to a life adverse event were more likely to experience dysfunctional eating patterns before bariatric surgery. One year after surgery, trauma-exposed patients from this study showed no difference in impulsive, compulsive and restrictive eating patterns neither in grazing nor in night eating behaviors. However, patients who experienced any lifetime traumatic event were more likely to overeat and to show difficulties following dietary guidelines 1 year after bariatric surgery, which is consistent with the results of previous studies showing that psychological distress may lead to poor compliance to medical and dietary recommendations after bariatric surgery (Guisado et al., 2001; Pessina, Andreoli, & Vassallo, 2001; Van Hout et al., 2005). Moreover, evidence from a systematic review suggested that appearance or reappearance of dysfunctional eating patterns after bariatric surgery was associated with poorer postoperative weight loss (Opozda, Chur-Hansen, & Wittert, 2016), and poor compliance to dietary and medical guidelines appears to be the main factor moderating this association (Pontiroli et al., 2007).

The results of the present study on the unequal exposure to traumatic life events between socio-professional classes are in accordance with studies indicating that trauma and multiple victimization are more common among people with low socioeconomic status and facing prolonged social adversities in their life-course (Harland, Reijneveld, Brugman, Verloove-Vanhorick, & Verhulst, 2002; H. A. Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006; R. J. Turner & Lloyd, 1995). Low household income, unemployment or an unstable employment, 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345

debts, loss of income, and the impact of discrimination based on class and gender are multifaceted stressful situations that limit all aspects of life (in particular, choice of neighborhood, schooling, leisure activities, and job opportunities). People with accumulative socioeconomic disadvantages not only meet poor availability of institutional resources (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000), but their close family and kinship circles are also less effective in giving them needed support in case of socioeconomic hardships. The findings suggest that a cross-sectional study on the specific influences of traumatic life events in preadolescent children located in two socioeconomically distinct neighborhood settings may help to clarify the non-significant effect of social class on the pre- and post-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns (Gustafsson, Larsson, Nelson, & Gustafsson, 2009). As this research showed, sociocultural disadvantage was significantly associated with emotional symptoms; whereas the type of traumatic life events was related to dysfunctional eating patterns.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the associations of trauma exposure with weight loss and dysfunctional eating patterns in a sample of 200 consecutive bariatric surgery patients in France up to 24 months after surgery. These clinical data were collected by the same team of clinicians, and systematically recorded in patients EMR during pre-operative and follow-up medical visits. Before surgery, the very same psychologist (DT) systematically investigated whether patients had been exposed to any traumatic event during their lifetime. These methodological features are the strengths of this study in so far as they provide scientifically meaningful and useable information.

On the other hand, the retrospective design of this chart review presents some limitations, mainly regarding the number of available data relevant to the main hypothesis of the present study. First, data collection may be biased in this study in so far as it has been collected through clinical interviews by the clinical staff. Thus, data collection may be 346 347 348 349 350 351 352 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368 369 370

unstandardized due to possible different ways of running an interview, which may in turn induce social desirably or barriers to provide accurate information. Second, the size of this study's sample and its distribution did not allow for statistically controlling potential moderating variables such as surgery technique or psychiatric comorbidities. Third, it would have been of great value to know whether patients ever sought psychological support after being exposed to any traumatic event, or to manage their eating patterns. In fact, weight loss maintenance have been associated with better internal motivation to lose weight, self-efficacy, autonomy and coping strategies, which are skills targeted through psychological support (Elfhag & Rössner, 2005). Fourth, while exposure to traumatic events is known to increase psychological distress (Brewerton, 2007) the actual emotional and cognitive impact of personal traumatic history remains unknown in this study.

Future investigations of the associations between trauma exposure and bariatric surgery outcome could adopt a prospective design from the first visit in the Nutrition Department to the last follow-up medical visit, using a standardized form to collect data of interest. Patients' expectations, medical and paramedical advice, as well as the actual emotional impact of a significant traumatic event could be strong moderators between trauma exposure and bariatric surgery outcomes. Bariatric surgery candidates with a history of trauma exposure (i.e., more than half of morbidly obese patients candidates to bariatric surgery) could benefit from closer medical, dietetic, and/or psychological follow-up care to avoid insufficient postoperative weight loss as well as reappearance of dysfunctional eating patterns after surgery.

371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390

References

Abilés, V., Rodríguez-Ruiz, S., Abilés, J., Mellado, C., García, A., Pérez de la Cruz, A., & Fernández-Santaella, M. C. (2010). Psychological characteristics of morbidly obese candidates for bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery, 20(2), 161–167.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-008-9726-1

Adams, S. T., Salhab, M., Hussain, Z. I., Miller, G. V., & Leveson, S. H. (2013). Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: What are the preoperative predictors of weight loss? Postgraduate Medical Journal, 89(1053), 411–416.

https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131310

Alvarez, J., Pavao, J., Baumrind, N., & Kimerling, R. (2007). The relationship between child abuse and adult obesity among California women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33(1), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.036

Andridge, R. R., & Little, R. J. A. (2010). A review of hot deck imputation for survey non-response. International Statistical Review, 78(1), 40–64.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-5823.2010.00103.x

Beck, N. N., Mehlsen, M., & Støving, R. K. (2012). Psychological characteristics and associations with weight outcomes two years after gastric bypass surgery:

Postoperative eating disorder symptoms are associated with weight loss outcomes. Eating Behaviors, 13(4), 394–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.06.001 Bentley, T., & Widom, C. S. (2009). A 30-year follow-up of the effects of child abuse and

neglect on obesity in adulthood. Obesity, 17(10), 1900–1905. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.160

Bocchieri-Ricciardi, L., Chen, E. Y., Munoz, D., Fischer, S., Dymek-Valentine, M., Alverdy, J. C., & le Grange, D. (2006). Pre-surgery binge eating status: Effect on eating

391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414

behavior and weight outcome after gastric bypass. Obesity Surgery, 16(9), 1198–1204. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089206778392194

Brewerton, T. D. (2007). Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: Focus on PTSD. Eating Disorders, 15(4), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260701454311

Brewerton, T. D., O’Neil, P. M., Dansky, B. S., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2015). Extreme obesity and its associations with victimization, PTSD, major depression and eating disorders in a National sample of women. Journal of Obesity & Eating Disorders, 1, 2–6. Burns, E. E., Fischer, S., Jackson, J. L., & Harding, H. G. (2012). Deficits in emotion

regulation mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and later eating disorder symptoms. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(1), 32–39.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.005

Canetti, L., Berry, E. M., & Elizur, Y. (2009). Psychosocial predictors of weight loss and psychological adjustment following bariatric surgery and a weight-loss program: The mediating role of emotional eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20592

D’Argenio, A., Mazzi, C., Pecchioli, L., Di Lorenzo, G., Siracusano, A., & Troisi, A. (2009). Early trauma and adult obesity: Is psychological dysfunction the mediating

mechanism? Physiology & Behavior, 98(5), 543–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.08.010

Dawes, A. J., Maggard-Gibbons, M., Maher, A. R., Booth, M. J., Miake-Lye, I., Beroes, J. M., & Shekelle, P. G. (2016). Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 315(2), 150.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18118

Dixon, J. B., Dixon, M. E., & O’Brien, P. E. (2003). Depression in association with severe obesity: changes with weight loss. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163, 2058–2065. 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 438 439

Elfhag, K., & Rössner, S. (2005). Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obesity Reviews, 6(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x

Fried, M., Yumuk, V., Oppert, J. M., Scopinaro, N., Torres, A. J., Weiner, R., … Frühbeck, G. (2013). Interdisciplinary European guidelines on metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obesity Facts, 6(5), 449–468. https://doi.org/10.1159/000355480

Gorin, A. A., & Raftopoulos, I. (2009). Effect of mood and eating disorders on the short-term outcome of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obesity Surgery, 19(12), 1685– 1690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-008-9685-6

Grilo, C. M., Masheb, R. M., Brody, M., Toth, C., Burke-Martindale, C., & Rothschild, B. S. (2005). Childhood maltreatment in extremely obese male and female bariatric surgery candidates. Obesity Research, 13(1), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2005.16 Guisado, J. A., Vaz, F. J., López-Ibor Jr, J. J., & Rubio, M. A. (2001). Eating behavior in

morbidly obese patients undergoing gastric surgery: Differences between obese people with and without psychiatric disorders. Obesity Surgery, 11(5), 576–580.

https://doi.org/10.1381/09608920160556751

Gunstad, J., Paul, R. H., Spitznagel, M. B., Cohen, R. A., Williams, L. M., Kohn, M., & Gordon, E. (2006). Exposure to early life trauma is associated with adult obesity. Psychiatry Research, 142(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2005.11.007 Gustafson, T. B., & Sarwer, D. B. (2004). Childhood sexual abuse and obesity. Obesity

Reviews, 5(3), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00145.x Gustafsson, P. E., Larsson, I., Nelson, N., & Gustafsson, P. A. (2009). Sociocultural

disadvantage, traumatic life events, and psychiatric symptoms in preadolescent children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(3), 387–397.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016559 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464

Harland, P., Reijneveld, S. A., Brugman, E., Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P., & Verhulst, F. C. (2002). Family factors and life events as risk factors for behavioural and emotional problems in children. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 11(4), 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-002-0277-z

Haute Autorité de Santé. (2009). Obésité: prise en charge chirurgicale chez l’adulte. Recommandations de bonnes pratiques professionnelles. Retrieved from

http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/jcms/c_765529/obesite-prise-en-charge-chirurgicale-chez-l-adulte

Haute Autorité de Santé. (2011). Surpoids et obésité de l’adulte : prise en charge médicale de premier recours. Retrieved from http://www.has-sante.fr

Herpertz, S., Kielmann, R., Wolf, A. M., Hebebrand, J., & Senf, W. (2004). Do psychosocial variables predict weight loss or mental health after obesity surgery? A systematic review. Obesity Research, 12(10), 1554–1569. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2004.195 Herpertz, S., Kielmann, R., Wolf, A. M., Langkafel, M., Senf, W., & Hebebrand, J. (2003).

Does obesity surgery improve psychosocial functioning? A systematic review. International Journal of Obesity, 27(11), 1300–1314.

https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802410

Husky, M. M., Mazure, C. M., Ruffault, A., Flahault, C., & Kovess-Masfety, V. (2017). Differential associations between excess body weight and psychiatric disorders in men and women. Journal of Women’s Health. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2016.6248 Karlsson, J., Sjöström, L., & Sullivan, M. (1998). Swedish obese subjects (SOS) - an

intervention study of obesity: two-year follow- up of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and eating behavior after gastric surgery for severe obesity. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 22, 113–126.

465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488

Kinzl, J. F., Schrattenecker, M., Traweger, C., Mattesich, M., Fiala, M., & Biebl, W. (2006). Psychosocial predictors of weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery, 16(12), 1609–1614. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089206779319301

Kubik, J. F., Gill, R. S., Laffin, M., & Karmali, S. (2013). The impact of bariatric surgery on psychological health. Journal of Obesity, 2013, 1–5.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/837989

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309

Livhits, M., Mercado, C., Yermilov, I., Parikh, J. A., Dutson, E., Mehran, A., … Gibbons, M. M. (2012). Preoperative predictors of weight loss following bariatric surgery:

Systematic review. Obesity Surgery, 22(1), 70–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-011-0472-4

MacCallum, R. C., Zhang, S., Preacher, K. J., & Rucker, D. D. (2002). On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.19

Meany, G., Conceição, E., & Mitchell, J. E. (2014). Binge eating, binge eating disorder and loss of control eating: Effects on weight outcomes after bariatric surgery. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(2), 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2273

Michopoulos, V., Powers, A., Moore, C., Villarreal, S., Ressler, K. J., & Bradley, B. (2015). The mediating role of emotion dysregulation and depression on the relationship between childhood trauma exposure and emotional eating. Appetite, 91, 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.03.036

Moulton, S. J., Newman, E., Power, K., Swanson, V., & Day, K. (2015). Childhood trauma and eating psychopathology: A mediating role for dissociation and emotion

489 490 491 492 493 494 495 496 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505 506 507 508 509 510 511 512 513

dysregulation? Child Abuse & Neglect, 39, 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.003

National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. (2000). Overweight, obesity, and health risk. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160(7), 898.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.7.898

Opozda, M., Chur-Hansen, A., & Wittert, G. (2016). Changes in problematic and disordered eating after gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding and vertical sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review of pre-post studies: Problematic/disordered eating in bariatric surgeries. Obesity Reviews, 17(8), 770–792. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12425 Palmisano, G. L., Innamorati, M., & Vanderlinden, J. (2016). Life adverse experiences in

relation with obesity and binge eating disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.018

Pataky, Z., Carrard, I., & Golay, A. (2011). Psychological factors and weight loss in bariatric surgery. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology, 27(2), 167–173.

https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283422482

Pessina, A., Andreoli, M., & Vassallo, C. (2001). Adaptability and compliance of the obese patient to restrictive gastric surgery in the short term. Obesity Surgery, 11(4), 459– 463. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089201321209332

Pontiroli, A. E., Fossati, A., Vedani, P., Fiorilli, M., Folli, F., Paganelli, M., … Maffei, C. (2007). Post-surgery adherence to scheduled visits and compliance, more than personality disorders, predict outcome of bariatric restrictive surgery in morbidly obese patients. Obesity Surgery, 17(11), 1492–1497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-008-9428-8

R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

514 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538

Robinson, A. H., Adler, S., Stevens, H. B., Darcy, A. M., Morton, J. M., & Safer, D. L. (2014). What variables are associated with successful weight loss outcomes for bariatric surgery after 1 year? Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 10(4), 697– 704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2014.01.030

Sarwer, D. B., Wadden, T. A., & Fabricatore, A. N. (2005). Psychosocial and behavioral aspects of bariatric surgery. Obesity Research, 13(4), 639–648.

Scott, K. M., Bruffaerts, R., Simon, G. E., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M., de Girolamo, G., … Von Korff, M. (2008). Obesity and mental disorders in the general population: results from the world mental health surveys. International Journal of Obesity, 32(1), 192– 200. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803701

Simon, G. E., Von Korff, M., Saunders, K., Miglioretti, D. L., Crane, P. K., Van Belle, G., & Kessler, R. C. (2006). Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(7), 824–830.

Thomas, C., Hypponen, E., & Power, C. (2008). Obesity and type 2 diabetes risk in midadult life: The role of childhood adversity. Pediatrics, 121(5), e1240–e1249.

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-2403

Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., & Ormrod, R. (2006). The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Social Science & Medicine, 62(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030

Turner, R. J., & Lloyd, D. A. (1995). Lifetime traumas and mental health: The significance of cumulative adversity. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(4), 360–376.

van de Laar, A. (2012). Bariatric outcomes longitudinal database (BOLD) suggests excess weight loss and excess BMI loss to be inappropriate outcome measures, demonstrating better alternatives. Obesity Surgery, 22(12), 1843–1847.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0736-7 539 540 541 542 543 544 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552 553 554 555 556 557 558 559 560 561 562 563

Van Hout, G. C. M., Verschure, S. K. M., & Van Heck, G. L. (2005). Psychosocial predictors of success following bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery, 15(4), 552–560.

https://doi.org/10.1381/0960892053723484

Wiederman, M. W., Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (1999). Obesity Among Sexually Abused Women: An Adaptive Function for Some? Women & Health, 29(1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v29n01_07

Wimmelmann, C. L., Dela, F., & Mortensen, E. L. (2014). Psychological predictors of weight loss after bariatric surgery: A review of the recent research. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 8(4), e299–e313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2013.09.003 Wood, K. V., & Ogden, K. (2012). Explaining the role of binge eating behaviour in weight

loss post bariatric surgery. Appetite, 59(1), 177–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.019 564 565 566 567 568 569 570 571 572 573 574 575 576

Table 1. Baseline characteristics by presence or absence of a traumatic experience. Variable Trauma (n=121) No trauma (n=79) p Socio-demographics Gender .742 Female 80.6% (100) 79.8% (63) Male 17.4% (21) 20.3% (16) Age (years) 44.4 (11.66) 44.3 (11.41) .976 Maximal BMI (kg/m2) 45.3 (5.97) 44.3 (7.70) .217 Pre-surgery BMI (kg/m2) 42.9 (5.52) 42.7 (5.50) .791 Socio-professional category .041 Higher class 13.2% (16) 26.6% (21) Middle class 58.7% (71) 54.4% (43) Other/inactive 28.1% (34) 19.0% (15) Lives… .235 With partner 60.3% (73) 69.6% (55) Alone 39.7% (48) 30.4% (24) Housing .359 Apartment 75.2% (85) 68.0% (51) House 24.8% (28) 32.0% (24) Children (number) 1.6 (1.24) 1.7 (1.46) .538 Obesity in family .297 Presence 68.3% (82) 76.3% (58) Absence 31.7% (38) 23.7% (18) Diabetes in family 1.000 Presence 47.5% (57) 47.4% (36) Absence 52.5% (63) 52.6% (40) Comorbidities Alcohol consumption 1.000 Presence 18.2% (22) 17.7% (14) Absence 81.8% (99) 82.3% (65) Tobacco consumption .566 Presence 24.8% (30) 20.3% (16) Absence 75.2% (91) 79.7% (63) Consumption (any) .767 Presence 34.7% (42) 31.6% (25) Absence 65.3% (79) 68.4% (54)

Obstructive sleep apnea 1.000

Presence 71.9% (87) 70.9% (56) Absence 28.1% (34) 29.1% (23) Diabetes .653 Presence 30.6% (37) 26.6% (21) Absence 69.4% (84) 73.4% (58) Osteoarthritis .399 Presence 81.8% (99) 87.3% (69) Absence 18.2% (22) 12.7% (10) 577

Surgery information

Surgical procedure .332

Gastric by-pass 52.9% (64) 55.7% (44) Sleeve gastrectomy 36.4% (44) 38.0% (30) Adjustable gastric band 0.8% (1) 2.5% (2)

Conversion (any) 9.9% (12) 3.8% (12)

Preparation for surgery (months) 12.3 (4.27) 13.2 (4.30) .291

Previous diets 1.000

Yes 95.8% (115) 94.9% (75)

No 4.2% (5) 5.1% (4)

Social support for surgery NA

Yes 100% (47) 100% (26)

No 0% (0) 0% (0)

Pre-surgery impulsive eating .052

Presence 39.7% (48) 25.3% (20)

Absence 60.3% (73) 74.7% (59)

Pre-surgery overeating .922

Presence 95.0% (115) 93.7% (74)

Absence 5.0% (6) 6.3% (5)

Pre-surgery atypical eating .523

Presence 51.2% (62) 45.6% (36) Absence 48.8% (59) 54.4% (43) Psychiatric information Mood disorder .337 Presence 27.3% (33) 20.3% (16) Absence 72.7% (88) 79.7% (63) Anxiety disorder .802 Presence 3.3% (4) 5.1% (4) Absence 96.7% (117) 94.9% (75) Intellectual disability NA Presence 0% (0) 0% (0) Absence 100% (121) 100% (79) Psychosis .708 Presence 0.8% (1) 2.5% (2) Absence 99.2% (120) 97.5% (77)

Psychiatric comorbidity (any) .551

Presence 28.9% (35) 24.1% (19)

Absence 71.1% (86) 75.9% (60)

Type of traumatic experience

Early experience of separation or loss 43.0% (52) Emotional abuse or neglect 31.4% (38) Dysfunctional family background 18.2% (22) Physical or sexual abuse 9.9% (12)

Note. Categorical variables are expressed as ‘percentage (n)’. Continuous variables are expressed as ‘mean (standard deviation)’. p values are from Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and Student’s t tests for continuous variables. Impulsive eating includes compulsive 578

579 580

and restrictive eating. Overeating includes disturbed eating. Atypical eating includes grazing and night eating syndrome. Missing data are removed from dataset for each variable.

581 582 583

Table 2. Associations of traumatic experience with post-surgery lower weight-loss.

Weight measure Time n % trauma % no trauma p OR 95% CI

%TWL (< median) 6 months 194 33.7 16.3 .017 2.06 1.15–3.84

12 months 200 29.5 20.5 .073 1.44 .97–2.16

24 months 100 33.7 16.3 .017 2.06 1.15–3.84

Note. BMI: Body Mass Index (kg/m2). %TWL: percentage of BMI loss from pre-surgery. 6 months %TWL median = 23.5% 12 months %TWL median = 29.3% 24 months %TWL median = 30.6% 584 585 586 587 588

Table 3. Associations of traumatic experience with pre- and post-surgery eating patterns at 12 months (total n = 200).

Time Eating patterns % trauma % no trauma p OR 95% CI

Pre-surgery Impulsive eating 24.0 10.0 .001 2.40 1.45–4.13

Overeating 57.5 37.0 .003 1.55 1.16–2.09

Atypical eating 31.0 18.0 .009 1.72 1.15–2.62

Post-surgery Impulsive eating 1.0 1.5 .657 .67 .09–4.02

Overeating 30.5 20.0 .038 1.53 1.03–2.29

Atypical eating 8.5 4.0 .079 2.13 .95–5.21

Note. Impulsive eating includes compulsive and restrictive eating. Overeating includes disturbed eating. Atypical eating includes grazing and night eating syndrome.

589

590 591 592

Figure 1. Flow chart of participation.

Figure 2. Proportion of total sample having pre-surgery higher BMI and post-surgery lower total weight-loss by presence or absence of any lifetime traumatic experience.

Note. BMI: Body Mass Index (kg/m2). %TWL: percentage of BMI loss from pre-surgery. Medians were used to dichotomize weight-related data at each time (pre-surgery median = 42.3 kg/m2; 6 months median = 23.5%; 12 months median = 29.3%; 24 months median = 30.6%).

Figure 3. Proportion of total sample having pre-surgery dysfunctional eating patterns by presence or absence of any lifetime traumatic experience.

Note. Impulsive eating includes compulsive and restrictive eating. Overeating includes disturbed eating. Atypical eating includes grazing and night eating syndrome.

Figure 4. Proportion of total sample having dysfunctional eating patterns 12 months after bariatric surgery by presence or absence of any lifetime traumatic experience.

Note. Impulsive eating includes compulsive and restrictive eating. Overeating includes disturbed eating. Atypical eating includes grazing and night eating syndrome.

593 594 595 596 597 598 599 600 601 602 603 604 605 606 607 608 609 610