The impact of reference pricing system on

brand name’s prices: the case of Tunisia

1Inès Ayadi

2Abstract

Many policies are planned to face the increasing rate in health costs. In such circumstances and in order to reduce the pharmaceutical expenses, Tunisia adopted a reform of Health Insurance System. We study the effect of the introduction of reference pricing on pharmaceuticals’ price. In this study we use data for four molecules from IMS Health database. The data span from the third quarter 2002 to fourth quarter 2008. First, we study competition effect on brand-names’ price and generic one. We find that the brand name price’s drop is more important than the average price of generic. Then, we examine the effect of the introduction of reference pricing (RP) on prices. It shows that the brand name’s price decline after the introduction of RP and generic competition has an important role in this process. We find that the RP system has a strong effect in terms of reducing prices of pharmaceuticals; the effect is stronger for brand-name than generic versions. This confirms that the RP encourages generic competition and induces generic switching.

Keywords: Pharmaceutical market in Tunisia, generic competition, reference pricing system,

panel data, prices.

1

This paper corresponds to chapter 1 of my PhD Thesis. Acknowledgements: I am especially grateful to Professors Marie-Eve Joel and Younès Boujélbène for their guidance. I would also to thank Professor Salma and the participants of the 9th International conference of Middle East Economic Association in 2010 for many helpful suggestions. I also thank IMS Health (Tunisia and Algeria) for permission to use their data.

2 LEGOS, Université Paris Dauphine and URECA, Faculté des Sciences Economiques et de Gestion de Sfax. E-mail : inesayadi@hotmail.com

1.

Introduction

The development and growth of the generic pharmaceutical industry over the past years has come in response to the rising costs of healthcare.

After patents on brand-name pharmaceuticals expire, firms enter the market and produce products which are identical (referred to as generic3 and typically dispensed under the chemical name of the active ingredient). The greater availability of substitutes is expected to trigger price decreases for brand-name drugs (Wiggins and Maness, 2004).

As a result, health insurance is keen to promote generic use among patients as well as it encourages generic competition by using a variety of policies with a view to maximize savings on drugs bill.

Policies encouraging the use of generics within health care systems have been at the centre of attention over the past decade for many reasons. Like many other countries, total expenditures on pharmaceuticals in Tunisia have continued to rise over time and have reached 607 million US$ in 2008, this represents less than 0.1% of global market estimated to 773 billion US $ (current prices)

Many countries, particularly in Europe and North America, have implemented aggressive generic policies aiming to contain the cost of prescribed medicines, where it appears to be easiest and where competition might enable this, namely in the off-patent sector. In this context, Tunisia has implemented a new Health Insurance reform, from the 1st of July 2007, regulators authorities have implemented reference pricing for generics and generic substitution, in addition to promoting generic prescribing.

This paper studies the effect of the introduction of reference pricing on pharmaceuticals prices.

We analyze the relationship between regulation, competition and pharmaceutical prices theoretically and empirically.

Thus, we use panel data covering the period from the third quarter of 2002 to the fourth quarter of 2008, which allows for variations in time (before and after reform).

3 Generic medicines are proven to be chemically and therapeutically equivalent to originator brands, but are in principle significantly cheaper because they are allowed to enter the market after the patent expiry of the originator brand.

This work is the first to focus on the Tunisian market (and added to other studies that have looked to other experiences of countries (mainly Western)). Indeed, it specifically analyzes the impact of implementing the system of reference rates coupled with the availability of generic drugs. It is important to consider these two regulatory schemes together, since the system of reference rates is accompanied by the promotion of generic drugs. Therefore, it is a study of the effect of generic drugs before and after the reform of the health insurance system in Tunisia.

The next section of this paper presents the characteristics of the pharmaceutical market in Tunisia. Section 3 summarizes prior findings reported in economic literature on generic competition and Reference pricing system and discusses the structure of the model. Section 4 describes the characteristics of the dataset and our sample. Section 5 discusses the estimation results. The final section draws the main conclusions.

2.

Characteristics of the Tunisian pharmaceutical market

The purpose of this paper is to examine the impact of reference pricing (RP) system on the pharmaceutical prices, dealing with both brand-name and generic drug producers. RP is a regulatory measure aimed at containing pharmaceutical spending by promoting the usage of lower-cost generic drug (Merino-Castello [2003]). We focus on the Tunisian case.

The procedure of generic entry is the same worldwide, however, due to different political, social and cultural rights, some countries exhibit high penetration rate, while others are unable to reach a significant market share. Several countries (mainly European, such as France, Denmark, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Spain, and Netherlands) have implemented different types of mechanisms of RP with significant variations between them. However, the principle remains the same: the price paid by the third party is established with reference to drugs interchangeable and any additional expenditure is charged to the consumer as an out-of pocket expense.

As in most other countries, the Tunisian pharmaceutical market is extensively regulated. Pharmaceuticals are subject to stringent regulations covering the import (through the

Pharmacie Centrale de Tunisie, a monopolistic state company importer), manufacturing, distribution and selling4.

Moreover, the local production of pharmaceuticals focuses on the manufacture of generic drugs and medicines under license. Between 2000 and 2005, the rate of generic drugs manufactured in Tunisia raised from 32.2 to 48.4%.

Pharmaceutical firms need approval to launch a new product in Tunisia5. Once this is obtained, prices are subject to controls. In addition, the drugs price homologation in particular at the stage of the distribution and retail, and their uniform application in Tunisia ensure that all patients pay the same price for their prescribed drugs6. The respect of the prices approved in pharmacy is strict due to the share of the official publication of these prices and in addition to many possibilities of control of their conformity.

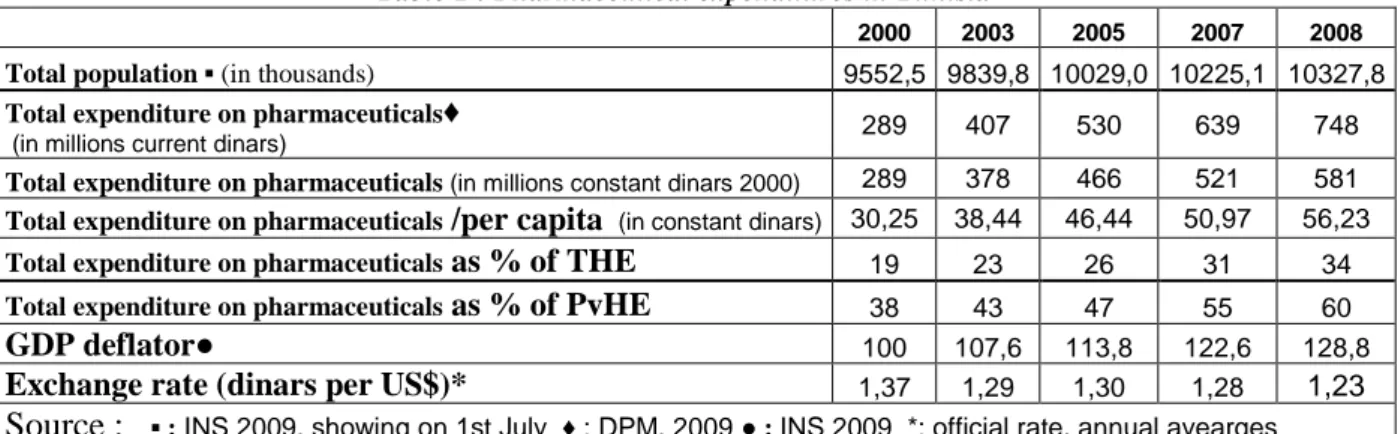

Although Tunisia has made progress in the health sector, it still faces rural and urban disparities in health outcomes and gaps in health coverage. Tunisia also shows inefficiencies in managing of health financing services, in delivery systems and pharmaceutical expenditures. The rising cost of prescribed medicines is a critical public policy issue confronting policymakers and consumers in Tunisia. Pharmaceuticals represent a significant part in both the total expenditure on health (THE) and the Private expenditure on health (PvHE).

Table 1 : Pharmaceutical expenditures in Tunisia

2000 2003 2005 2007 2008

Total population ▪ (in thousands) 9552,5 9839,8 10029,0 10225,1 10327,8

Total expenditure on pharmaceuticals♦

(in millions current dinars) 289 407 530 639 748

Total expenditure on pharmaceuticals (in millions constant dinars 2000) 289 378 466 521 581

Total expenditure on pharmaceuticals /per capita (in constant dinars) 30,25 38,44 46,44 50,97 56,23

Total expenditure on pharmaceuticals as % of THE 19 23 26 31 34

Total expenditure on pharmaceuticals as % of PvHE 38 43 47 55 60

GDP deflator● 100 107,6 113,8 122,6 128,8

Exchange rate (dinars per US$)* 1,37 1,29 1,30 1,28 1,23

Source : ▪ : INS 2009, showing on 1st July ♦ : DPM, 2009 ● : INS 2009 *: official rate, annual avearges

4 The Law No. 85-91 of 22 November 1985 regulates the manufacture and registration of medicines for human medicine in Tunisia

5

Regulation of therapeutic goods known as Autorisation de Mise sur le Marché (AMM) delivered by la Direction de la Pharamcie et du Médicament (DPM)

6 The medicines prices’ in Tunisia are set by the Pharmacie Centrale de Tunisie, in other words, these prices are not determined by supply and demand. Thus, it is anticipated that prices have no effect on the demand for drugs in Tunisia.

To contain pharmaceutical expenditures and to control health costs, Tunisia has adopted Health Insurance reform since the 1st of July 2007. For pharmaceuticals, reform can be summarized in setting a rate of reimbursement according to the therapeutic value of medicines7 and the Reference pricing system8. Under this system drugs are grouped (or clustered) according to chemical or therapeutic equivalence. Then a single reimbursement level (the RP) is set for the whole cluster.

3.

Evidence from the literature and conceptual framework

This study can be divided into two parts. In the first one, we will focus on the effect of generic entry on prices. The second part emphasizes on the introduction of reference pricing. It is important to study those two parts together for the reason that RP level is the less expensive generic.

3.1 The effect of generic entry in prices

When a pharmaceutical patent expires, generic firms may enter the market and sell copies of the brand-name (original) drug. As generic drugs contain the same active chemical molecules, these are certified to be perfect substitutes to the brand-name drug.

Generic medicines are thought to compete on price with the originator brand but it they do not automatically lead to lower drug prices due to generic penetration.

Overall, it is difficult to draw general conclusions from the empirical literature because of methodological differences in the range of products considered, in the extent to which generics were included and, the nature of the data used.

In fact, the effects of generic entry on branded prices are a source of debate in the literature. Some studies (e.g., Saha et al. [2006], Wiggins and Maness [2004], Caves et al. [1991]) have estimated a negative relationship while others (e.g., Regan [2008], Frank and Salkever [1997], Grabowski and Vernon [1992]) have uncovered a positive relationship. This conflict between these last observations and the traditional analysis is known as "Generic Competition

7

With the reform, pharmaceuticals are classified into 4 groups according their therapeutic value: Vital with full reimbursement, Essential where the reimbursement rate is 85%, Intermediate as the rate is 40% and Comfort where the pharmaceuticals will be excluded from reimbursement.

8 The first reference price system was introduced in Germany, with the implementation of the Health Care Reform Act in 1989.

Paradox" advanced by Scherer [1993] who concludes that the high penetration of generic drugs does not necessarily reduce the price of brand drug.

Several studies provide conclusions on the nature of competition in the market for pharmaceuticals after patent expiration. Grabowski and Vernon [1992] examine the effect of generic entry in the US market on prices for 18 drugs that were first exposed to generic competition during the years 1983 through 1987. Their descriptive statistics reveal that the branded drug price increased by an average of 7 percent one year subsequent to generic entry and 11 percent two years after generic entry. At the same time generic prices continue to fall after first entry. The average generic price two years after entry was 35 percent lower than the first entry price. Frank and Salkever [1997] arrived at similar results when they looked at a sample of 32 drugs that lost patent protection during early to mid-1980s. More competition among generic drug producers is found to cause price reductions for those drugs. Increased competition from generic drugs, however, is not accompanied by lower prices on branded drugs. Their results suggest instead a small price increase on branded drugs. In a recent paper, Regan [2008] proposed a generalized model of Frank and Salkever [1992]. She examines how generic entry affects the price on the U.S. market for prescription drugs. Her findings suggest that price competition in the market for prescriptions is limited to the generic market: generic entry has a positive effect on the price of medicines and a negative impact on generic prices. Specifically, each entry is associated with a 1 percent increase of the brand-name price. The results validate the "Generic Competition Paradox".

Caves et al. [1991] investigate the experience of 30 drugs that lost patent protection between 1976 and 1987. Their result differs from that of Frank and Salkever [1997]. The branded drug price declines with the number of generic entrants, but the rate of decline is small. For the mean number of generic drugs, the brand name price declines by 4.5 percent only. At the same time, generic prices are much lower than the brand name prices. Their results suggest that average generic price is about 50 percent of the branded drug price when 3 generic producers have entered the market.

In the same context, Wiggins and Maness [2004] show that prices decrease with the increasing number of pharmaceutical manufacturers. The analysis used a data set covering all anti-infective products and showed that initial entry led to sharp price reductions, with prices falling from the range of more than $60 per prescription for single sellers, $30when there are

two or three sellers. The results also show that prices continued to decline with additional entry.

Those various papers have a common conclusion: the brand-name price is much higher than generic prices.

The conceptual framework for this paper is borrowed from Frank and Salkever's [1992] market segmentation model. This model examines the effect of generic entry on branded prices. The model assumes that brand-name manufacturers behave as a Stackelberg price leader. The brand-name drug producer is the dominant firm which maximizes its profit taking account of the reaction to its pricing choices in the generic market. The producers of generic versions are viewed as fringe firms playing a Nash-Cournot no cooperative game. Each of these firms takes the brand-name producer’s price and the behaviour of rival generic producers as given in making its profit-maximizing pricing decision.

The implications of this model for empirical analysis can be summarized in two basic equations:

• The equation of the band name price can be formulated as follows: ܲp= ݂(ܰܩ, ݓ) (1)

Where ܲp : brand name’s price. NG: number of generic versions of the given brand-name (or

given molecule).w: vector of input prices.

• The equation of the generic drug prices can be written as: ܲG= ݂(ܰܩ, ܲp) (2)

with: ܲG : generics prices. NG: number of generic versions of the given brand-name (or given

molecule). ܲp : brand name’s price.

Following Grabowski and Vernon [1992] and Saha and al. [2006], we can write:

ln (

i t)

0 1 2P

i t i t

P

= α

+ α Τ + α

N G

+ ε

(1.1) The dependent variable is the natural logarithm of the brand price deflated by the pharmaceutical price index9. On the right hand side, T is a time trend, NG: number of generic versions. In (1.1), α1 indicates the variation in percentage of price each year and α2 gives the price variation in percentage due to an additional generic.9

Therefore, if the diffusion of generics reduces the brand-name price, as in Caves and al. [1991], α2 will be negative; otherwise, it will be positive suggesting that the diffusion of generics increases the brand-name price, as in Regan [2008].

The main difference between generic and brand-name drugs in the theoretical model presented above is that the brand-name product is supposed to have a greater market share compared to its generic competitors, because of consumer preference for brand-name. In relevance with this important market share, it is assumed that any change in the brand-name price’s have a significant impact on the price of generics.

Following Frank and Salkever [1997], we can write:

0 1 2 3

ln(

)

ln(

)

it it G P it itP

= + Τ+

β β

β

NG

+

β

P

+

µ

(2.1)The dependent variable is the natural logarithm of the average price of generics deflated by the pharmaceutical price index.

Referring to the literature which agrees that there is competition in the generics market, β2 is expected to be negative (Caves et al. [1991], Wiggins and Maness [2004], Reiffen and Ward [2005], Saha and al. [2006] and Regan [2008]). It is the price elasticity of generics.

3.2

The effect of reference pricing on prices

According to a review on the reference pricing (RP) system, the existing literature on the impact of such reimbursement mechanism has been mainly descriptive (Lopez-Casasnovas and Puig-Junoy [2001]). However, few authors have looked into the problem from a theoretical or empirical viewpoint.

In a theoretical paper, Danzon and Liu [1996] argue that all prices within the cluster will converge towards the RP, implying a price decrease on the high-price (brand-name) drugs and a price increase on the low-price (generic) drugs. In the same line, Zweifel and Crivelli [1996] provide a theoretical model on the German system and analyzed the responses of prices to the introduction of reference pricing. They suggested that the RP system produces an immediate reduction in brand-name prices to RP level but this system has no effect on generics because prices are close to the reference pricing.

However, more recent studies, find negative effects of reference pricing on brand-names and also generics. Pavcnik [2002] analyses the impact of the introduction of Reference pricing10 in Germany in 1989 on pharmaceutical prices. Using data on two different therapeutic fields (oral antidiabetics and antiulcerants) for the time period 1986–1996, she identifies strong price decreases for both brand-names and generics, and the price on branded drugs fell on average by more than the price on generic drugs. The price drop on branded drugs increases with the number of generics in the market, concluding that generic competition laid an important role in this process.

Brekke et al. [2009] found the same result as Pavcnik [2002] observing the response of the brand-name drug and generic version for RP system. They find that the RP system introduced in Norway has a strong price reducing effect on the drugs exposed to this regime, with the effect being stronger for brand-names (18–19 percent) than generics (7–8 percent). This confirms that reference pricing triggers price competition within the cluster of drugs exposed to the regime. Since the RP system in Norway included off-patent products only, the identified price effect is solely due to generic competition triggered by the reform.

In this section, we closely follow Brekke et al. [2009] and Pavcnik [2002]. The introduction of RP system in Tunisia, as the maximum level of reimbursement is related to the classification of the molecule. In fact, for pharmaceuticals in the category Vital, the RP system has no effect, while for the molecule classified as Essential, there is a maximum level of reimbursement, called the reference pricing which equals the cheapest generic.

For each of the equations estimated above, we use two dummy variables: RP : an indicator as it is equal to one if the product i at time t is covered by the system of Reference pricing. Moreover, we consider the class of the molecule, the dummy in this case Class this variable takes the value one for the category of essential medicines (for which there is a ceiling for reimbursement) and zero for vital pharmaceuticals.

So, we can rewrite:

0 1 2 ln( ) RP RP*Class)* it P it it it P = α + α Τ +δ1 + ((δ2 NG ) + α NG + ε (1.2) 10

In this equation, we apprehend the effect of the introduction of Reference pricing system. The interaction (RP*Class) indicates the link between the pharmaceutical category and the RP system. The interaction between (RP*Class) and NGis the number of generics covered by the RP system. This interaction is based on the study of Pavcnik [2002] which estimates the impact of the RP system based on the temporal and the control group because of the gradual implementation of reform.

To identify the effect of reform on generics, we extend equation (2.1) incorporating the two variables. 0 1 2 3 2 3 ln ( ) R P R P * C la s s )* ln ( ) ) R P * C la s s )* ln ( ) it it it G P P it it it P P N G P N G β β λ λ λ β β µ 1 = + Τ + + (( + (( ) + + + (2.2)

Having panel data, we are able to compare changes in intertemporal prices before and after the imposition of reform. Therefore, identification based not only on comparisons of before-after, but also on the comparison of price changes for pharmaceuticals subject to reform with changes in prices for pharmaceuticals not subject to reform.

In addition, the reform of the Tunisian Health Insurance covers the majority11 of the population and provides coverage of pharmaceutical prescribed. This statement can address the issue of the effect of the reform without going into details of the insurance plan. In addition, since the population has the same coverage (in the old regime, there were several forms of coverage and this was regarded as a limit, prompting the reform), so the selection problem does not present (Pavcnik [2002]).

4.

Data and descriptive results

In this paper we use proprietary data on a selection of off-patent medicines from Intercontinental Medical Statistics (IMS) Health. Their database provides quarterly time-series information on sales value and volume for each package of drugs sold on the Tunisian pharmaceutical market. The data from IMS Health contains also information on product’s active ingredient, manufacturer, launch date, and whether it is a brand-name or a generic. The data spans from the third quarter of 2002 to the fourth quarter of 2008.

The objective of this paper is to study the effect of the reform of Health Insurance in terms of pharmaceuticals, which it revolves around two concepts: the reference

11 The scheme applies to all health insurance schemes, with the exception of those students, low income workers who continue to receive benefits before. (Decree No. 2007-1366 of 11 June 2007)

pricing and the reimbursement by the therapeutic value of the molecule. Furthermore, health insurance scheme in Tunisia is being phased in gradually

select the data for estimation.

For the first step of the reform, we choose three molecules

using two criteria: the prevalence of diseases and the classification of molecules of therapeutic interest. After selecting APCI (diseases), we proceeded to select molecules to estimate among different regimens. The main criterion for selecting molecule is the exist

name drug and at least one generic competition and the system of

illnesses, we take the example is the study of the molecule

So, we consider a panel data with strength and package size). Erreur

our dataset, the therapeutic classes to which they and the number of generic substitutes in Tunisia.

Table 3 data reveal considerable

INN Therapeutic class

Captopril Hypertension Carbamazepine Anticonvulsant

Glibenclamide Anti-diabetic Amoxicillin Antibiotics/anti

infectives

In consequence, our panel regroups 11 drugs.

to look at how average prices have developed over time. In pharmaceuticals prices.

With time measured in quarter period,

the figure. The average prices of the drugs subject to RP display a

the implantation of the reform. This corresponds well with the results present in Brekke et al. [2009].

12 The first phase commenced on the 1 (Affections Prises en Charge Intégralement

“childbirth” in public and private health institutions. The second phase is related to common diseases became effective from the 1st of July 2008.

13 The three molecules (International Nonproprietary Names

Glibenclamide (anti-diabetic drug) and Carbamazepine (anticonvulsant). 14 This number is different within package size and strength

name drug.

and the reimbursement by the therapeutic value of the molecule. Furthermore, scheme in Tunisia is being phased in gradually12; this is considered

For the first step of the reform, we choose three molecules13 for full paid diseases (APCI) criteria: the prevalence of diseases and the classification of molecules of therapeutic After selecting APCI (diseases), we proceeded to select molecules to estimate among

The main criterion for selecting molecule is the exist

and at least one generic version, to determine, first, the effect of generic competition and the system of reference pricings. For the second stage of reform on common

esses, we take the example is the study of the molecule amoxicillin.

, we consider a panel data with the various sales presentations (taking into account the

Erreur ! Source du renvoi introuvable. lists

our dataset, the therapeutic classes to which they belong, the ATC-code, the brand and the number of generic substitutes in Tunisia.

considerable variability in the degree of generic penetration across Table 2 : Description of drugs

Therapeutic class ATC Code Brand-Name

Drug

Hypertension C09AA01 Lopril nticonvulsant A10BB01 Tégretol

diabetic N03AF01 Daonil

Antibiotics/anti-infectives J01CA04 Clamoxyl

In consequence, our panel regroups 11 drugs. A natural starting for the descriptive analysis is to look at how average prices have developed over time. In Figure

With time measured in quarter period, reference pricing (RP) was introduced in period 20 in . The average prices of the drugs subject to RP display a pronounced decrease after implantation of the reform. This corresponds well with the results present in Brekke et al.

first phase commenced on the 1st of July 2007 and concerned the “heavy and costly diseases full paid” Intégralement, APCI) such as diabetes, hypertension; “monitoring pregnancy” and c and private health institutions. The second phase is related to common diseases became The three molecules (International Nonproprietary Names: INN) are: Captopril (treatment of hypertension),

diabetic drug) and Carbamazepine (anticonvulsant).

This number is different within package size and strength; so, we give the sum of the generics for each brand and the reimbursement by the therapeutic value of the molecule. Furthermore, the new

considered when we

for full paid diseases (APCI) criteria: the prevalence of diseases and the classification of molecules of therapeutic After selecting APCI (diseases), we proceeded to select molecules to estimate among The main criterion for selecting molecule is the existence of the

brand-to determine, first, the effect of generic stage of reform on common

the various sales presentations (taking into account the lists all components in code, the brand-name drug

in the degree of generic penetration across drugs.

Number of generic substitutes14 in Tunisia 4 2 2 3

A natural starting for the descriptive analysis is

Figure 1 , we plot

was introduced in period 20 in pronounced decrease after implantation of the reform. This corresponds well with the results present in Brekke et al.

of July 2007 and concerned the “heavy and costly diseases full paid” , APCI) such as diabetes, hypertension; “monitoring pregnancy” and c and private health institutions. The second phase is related to common diseases became are: Captopril (treatment of hypertension), ; so, we give the sum of the generics for each

brand-Table 3 defines variables used in the regression analysis and contains descriptive statistics.

The minimum and maximum values of the key variables suggest a high degree of heterogeneity across drugs and over time. The variance of the brand-name drug price is significant; the minimum value is 1.7 while the maximum value is 18 dinars, while the average price of generics fluctuates between 1 TND and 13 TND. The number of generic competitors ranges between 1 and 4.

Figure 1: Pharmaceutical prices

Table 3 : Definition of variables and descriptive statistics Variables Definition Mean Standards

Dev. Minimum Maximum P

P

Brand-name Pharmaceutical Price Index (in TNDprice deflated by 15) the 6.606 4.401 1.744 18.033G

P Average price of generics by the Pharmaceutical Price Index (in TND) 4.377 3.080 1.059 13.058 NG Number of generic substitutes 2.087 0.942 1.000 4.000

15

Tunisian Dinar

pharamaceutical prices

brand-name price average price of generics

4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

5.

Empirical results

We begin by discussing several estimated issues before presenting the results of (1) and (2).

First, when considering a sample of panel data, we should check if the specification is homogeneous or heterogeneous process data generator.

Hausman tests16 reject that the regressors are not correlated with the error term in all of the reported regression in this paper, so the fixed effect estimation yields consistent and efficient estimates of the coefficient. All of the reported results in the paper use this specification. Tables 4 and 5 summarise the empirical statistics for brand-name price and generic regression respectively.

Second, for the different substances, the price (generics and brand-name drugs) does not change substantially between 2007and 2008 (the period during which the Reference pricing system is active in the data), which makes it difficult to identify simultaneously

δ

1 (λ1 forgenerics) and

δ

2 (λ2 for generics) andλ

3. We have estimated different versions of bothequation (1.2) and (2.2); one in which δ1

(

orλ1)

=0 and the other where δ2(

orλ2)

=0 and3 0

λ

= . Note that, if the relative price is roughly constant, the data used in the estimation of the interaction dummy variable resembles a linear transformation of the data used when estimating the intercept dummy variable. As a consequence, we would expect the two versions of the extended model to provide qualitatively similar results. This is also what happens: the intercept dummy variable is significant in the same cases as the interaction dummy variable, and the estimated relative price effects are more or less the same in both versions of the model. Therefore, we only present results corresponding to the version of the extended model, where "the interaction dummy variable" is set equal to zero (Aronsson et al. (2001)). 17Third, our analysis relies on intertemporal variation before and after the change in Health Insurance. In order to check the robustness of our results for the unobserved time varying factors that impact prices, we compare results without time controls to results with a time trend. Without time controls, we attribute all uncontrolled intertemporal variation in prices

16 An F-test supports the drug-specific effects 17

before and after the reform to changes in insurance. The second approach, the inclusion of a time trend (T) implies that changes in insurance lead to a price shift but do not affect the price trend.18

Table 4 reports the estimates of the regression of brand-name price before and after the

introduction of reference pricing system.

In the first column, we present the results of the effect of generic entry on brand-name price. Generic entry has a negative and statistically significant effect on the real price of a branded prescription; it decreases the average price by 9.8 percent. The brand-name price is negatively influenced by the generic competition. We observe the same results as Saha et al. (2006) that show that brand prices do react to generic competition; each additional entrant is associated with a 0.2 percent average decline in brand prices. So, the result found is consistent with the traditional model where the market presence of generic pharmaceutical market, offers the possibility to choose between substitutes, which forced down the brand-name price (e.g. Caves et al. [1991], Wiggins and Maness [2004]).

Table 4 : Brand-name drug price regression Dependant variable : ln of

brand-name real price

The Effect of Generic Entry on brand-name prices

(Equation (1.1))

The Effect of reference pricing system on brand-name price (Equation (1.2)) Number of generics -0.103 (0.025)* -0.131 (0.025)*

Dummy variable of reference pricing

--- -0.116 (0.023)* Time trend -0.004 (0,001)* -0.004 (0.001)* R² 0.974 0.976 F-statistic F(10,273)=957.535 F(10,272)=1013.89162 ²

χ

χ

²(3)=39.726119χ

² (4)=54.396977 Number of Observations 286 286* Equations (1.1) and (1.2) are estimated by Fixed Effect, after rejecting the null hypothesis. The level of significance is 1%. Into parenthesis, we present the standards deviations.

The descriptive statistics presented in section 4 suggest a strong negative price response for brand-name subject to reference pricing.

The negative coefficients in columns 1-3 suggest that brand-name prices drop significantly after the introduction of reference pricing system. The estimates range from 9.8 to 12.3%.

In the theoretical part, it states that generic and brand-name drug did not react the same way.

18

In Appendix 2, we estimate the equations (1.2) and (2.2) using no additional time controls, adding a time trend

Table 5 reports the estimates for generics regressions.

Column 1 indicates that the relationship between brand-name and generic substitute is a leader and follower one. In fact, the leader (brand-name) and its price follower (generic version) are aligned with competitive pricing. For the period from the third quarter 2002 to the fourth quarter 2008, increasing the brand-name price reduces the average price of generic substitutes by 15.7 percent. We note that the coefficient of number generics NG is negative and significant: each additional entrant is associated with a 4.1 percent average decline in average price of generics. Furthermore, we perceive that average price of generics declines over time, faster than the brand-name price. Thus, the negative sign indicates that the generic set their prices lower than that of the brand-name, which gives them the opportunity to increase their market share.

These results do not line up exactly with those of Frank and Salkever [1997] where they found that the number of generic negatively influence the average price of generic versions. However, they find that the coefficient of the price of the brand-name is positive but not significant. This difference is due to the concept of market segmentation of drugs proposed by Frank and Salkever [1992]. Reiffen and Ward [2005], meanwhile, found that generic prices decline with the number of generic manufacturers.

Table 5 : Generic price regressions

Dependant variable : ln of average

real price of generics substitutes

The Effect of Generic Entry on generic price (Equation (2.1))

The Effect of reference pricing system on generics’ price

(Equation (2.2))

Ln of brand-name real price -0.171

(0.036)* -0.216 (0.037)* Number of generics -0.042 (0.016)* -0.013 (0.004)*

Dummy variable of reference pricing --- -0.060

(0.001)* Time trend -0.012 (0.001)* -0.013 (0.001)* R² 0.991 0.991 F-statistic F(10,273)= 85.16547 F(10,271)=667.38522 ²

χ

χ

² (3)=1022.192427χ

² (5)=1497.778706 Number of Observations 286 286* Equations (2.1) and (2.2) are estimated by Fixed Effect, after rejecting the null hypothesis. The level of significance is 1%. Into parenthesis, we present the standards deviations.

In column 2, the results suggest that generic producers respond sharply to changes in pharmaceutical reimbursement (i.e. the introduction of reference pricing)

Generic competition reduced the average price of generic by 1.3% if we consider the system of reference pricings and 4.1% if not.

A possible explanation for this decline in prices could be the convergence of prices towards the PR, as suggested by Danzon and Liu [1996] and Danzon and Ketcham [2004]. The results suggest that the response of prices to changes in the reimbursement system is significant. The estimates confirm the evidence that reimbursement changes affect brand-name and generic versions differently (Pavcnik [2002]). Zweifel and Crivelli [1996] suggest that the reform produced a significant immediate decline in brand-name price to the RP level, while had little impact on generic prices. This same conclusion is found in this analysis. We find that the average price of generic drop, but this reduction is much more pronounced for brands. This suggests that brand-name producers need to significantly decrease the premium to protect their market shares as patients actually perceive the price of a product.

Given the importance of generic products in the pharmaceutical market, we can verify whether generic competition influences the price response of products to changes in insurance. If products lower their prices because they effectively face more price competition from generics after the changes in insurance, the coefficient on the interaction between the number of generics and the RP indicator should be negative. The results in Table 6 and

Erreur ! Source du renvoi introuvable. in Appendix 1 support this hypothesis. Columns 3

in both tables allow the number of generics to affect prices differently before and after the introduction of reference pricing system. The coefficient on the interaction of PR and the number of generics is negative. The importance of generic competition is more pronounced for brand-name drug: the coefficient on the interaction of PR indicator, brand, and the number of generics is always negative and significant.

Our results are in the same line as Brekke et al. [2009] who found that the introduction of Reference pricing led to an average price reduction of about 18 percent on brand-names and 8 percent on generics. The same result is found by Bergman and Rudholm [2003], which quantifies this fall, and it is of the order of 16-21%.

The number of generic manufacturers is important to explain price changes. The negative sign of the coefficient of the number of generic means that the brand-name prices and the average price of generic decrease with the increasing number of generics.

6.

Conclusion

Our econometric analysis leads us to make several observations. First, it appears that more competition among generic drug producers is linked to price reductions for those drugs. Second, increased competition from generics is accompanied by lower prices for brand-name drugs. Generic competition seemsto play an important role in this process.

We analysed the relationship between reference pricing (RP) system and pharmaceutical firms’ pricing strategies. Our analysis showed that the reference pricing system induced lower prices of both brand-names and generics exposed to the system. We find that, under RP system, branded drug producer decrease price substantially in order to adapt to the new competitive situation while generic prices decrease less. This confirms that reference pricing triggers price competition within the cluster of drugs exposed to the regime. This result match with the results of the literature which state that reduction in the brand-name price is more important because of its high level, initially, compared to generic versions.

Finally, the principal limitation to our analysis, concern the short observation period after the reform in 2007 (maximum six quarters). In this paper, we tried to present partial results on the effect of the introduction of reference price on prices. Future researches will be interested in the effect of this regime on the others participants in the process of consumption of pharmaceutical products (patients, pharmacists and doctors).

References

1. Bergman M.A, Rudholm N, The relative importance of actual and potential competition: empirical evidence from the pharmaceuticals market, The Journal of Industrial

Economics, December 2003, volume L1, number 4, p. 455-467

2. Brekke K.R, Grasdal A.L, Holmas T.H, Regulation and pricing of pharmaceuticals: Reference Pricing or Price Cap Regulation? European Economic Review, February 2009,

volume 53, issue 2, p.170-185

3. Caves R.E, Whinston M.D, Hurwitz M.A, Pakes A, Temin P, Patent Expiration, Entry, and competition in the US pharmaceutical industry, Brookings Papers on Economic

4. Frank R.G, Salkever D.S, Generic entry and the pricing of pharmaceuticals, Journal

of Economics& Management strategy, spring 1997, volume 6, number 1, p.75-90

5. Frank R.G, Salkever D.S, Pricing, Patent loss and the market for pharmaceuticals,

Southern Economic Journal, October 1992, p.165-179

6. Danzon P, Ketcham J, Reference pricing of pharmaceuticals for Medicare : evidence from Germany, the Netherlands and New Zealand, NBER Working Paper n°10007,

September 2003

7. Danzon P, Liu H, Reference pricing and physician drug budgets: the German experience in controlling pharmaceutical expenditures, Working paper, Philadelphia, The

Wharton School, 1996

8. Grabowski H, Vernon J.M, Brand loyalty, entry, and price competition in pharmaceuticals after the 1984 drug act, Journal of Law &Economics, October 1992,

volume 35, p.331-350

9. Lopez-Casanovas G, Puig-Junoy J, Review of the literature on reference pricing,

Health Policy, volume54, issue 2, November 2000, p. 87-123

10. Pavcnik N, Do pharmaceutical prices respond to potential patient out of pocket expenses?, The RAND Journal of Economics, autumn 2002,volume 33, number 3, p. 469-487 11. Regan T, Generic entry, price competition and market segmentation in the prescription drug market, International Journal of Industrial Organisation, 2008, number 26,

p.930-948

12. Reiffen D, Ward M.R, Generic Industry dynamics, Review of Economics and

Statistics,2005, number 87, p.37-49

13. Saha A, Grabowski H, Birnbaum H, Greenberg P, Bizan O, Generic competition in the US pharmaceutical industry, International Journal of the Economics of Business, Feb

2006, volume 13, issue 1, p15-38

14. Scherer F.M, Pricing, profits and technological progress in the pharmaceutical industry, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 1993, volume 7, number 3, p377-388

15. Wiggins S.N, Maness R, Price competition in pharmaceuticals: the case of anti-infectives, Economic Inquiry, April 2004,volume 2, number 2, p.247-263

16. Zweifel P, Crivelli L, Price regulation of drugs: lessons from Germany, Journal of

Appendix 1

Table 6: Brand-name price regression Dependant variable : lng of

brand-name real price

The Effect of Generic Entry on brand Prices (Equation (1.1))

The Effect of reference pricing system on brand-name price (Equation (1.2)) Number of generics -0.103 (0.025)* -0.131 (0.025)* -0.100 (0.031)*

Dummy variable of reference

pricing ---

-0.116

(0.023)*

---Number of generics with

reference pricing --- ---0.002 (0.010)* Time trend -0.004 (0,001)* -0.004 (0.001)* -0.001 (0.001)* R² 0.974 0.976 0.974 F-statistic F(10,273)=957.535 F(10,272)=1013.89162 F(10,272)=947.05867 ²

χ

χ

²(3)=39.726119χ

² (4)=54.396977χ

² (4)= 41.054372 Number of Observations 286 286 286Table 7: Generic price regression Dependant variable : ln of average

real price of generics substitutes

The Effect of Generic Entry on generic price (Equation (2.1))

The Effect of reference pricing system on generics’ price (Equation (2.2))

Ln of brand-name real price -0.171 (0.036)* -0.216 (0.037)* -0.157 (0.035)* Number of generics -0.042 (0.016)* -0.013 (0.004)* - 0.006 (0.002)*

Dummy variable of reference pricing

--- -0.060

(0.001)*

---Number of generics with reference

pricing

--- --- -0.057

(0.012)*

Ineraction between brand-name price and dummy variable of RP

--- --- -0.021 (0.009)** Time trend -0.012 (0.001)* -0.013 (0.001)* -0.013 (0.001)* R² 0.991 0.991 0.992 F-statistic F(10,273)= 85.16547 F(10,271)=667.38522 F(10,271)=94.4187 ²

χ

χ

² (3)=1022.192427χ

² (5)=1497.778706χ

² (6)=1322.439382 Number of Observations 286 286 286Appendix 2

: The effect of Reference Pricing using Time Trend and no Time controlsDependant variable : ln of brand-name real price With Time trend No Time controls

Number of generics -0.131 (0.025)* -0.144 (0.025)*

Dummy variable of reference pricing -0.116 (0.023)* -0.063 (0.019)*

R² 0.976 0.975

Dependant variable : ln of average real price of generics substitutes With Time trend No Time controls

ln of brand-name real price -0.216 (0.037)* -0.311 (0.052)*

Number of generics -0.013 (0.004)* -0.021 (0.007)*

Dummy variable of reference pricing -0.060 (0.001)* -0.122 (0.015)*