Unequa l Ageing in Europe

Women’s Independence and Pensions

Gianni Bet ti, Francesca Bet tio,

T homas Georgiadis, and

Platon Tinios

Con t en ts

List of Figures and Tables vii

Acknowledgments xi

List of EU Countries’ Abbreviations xiii

1 Women, Old Age, and Independence: Why Investigate

Yet Another Gender Gap? 1

2 Concepts and Literature 15

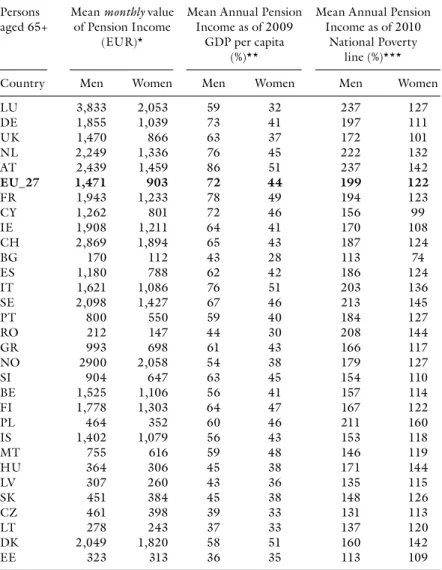

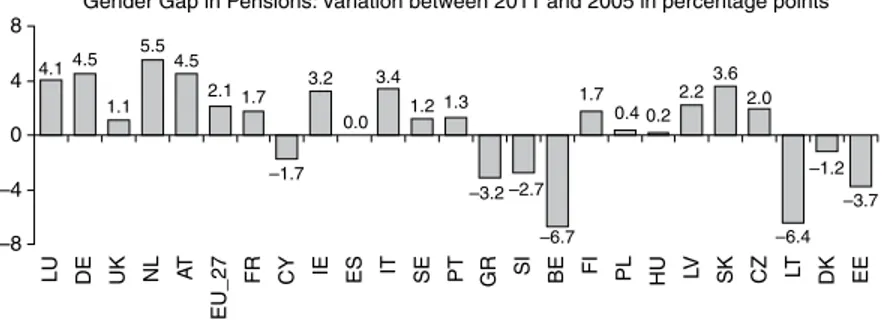

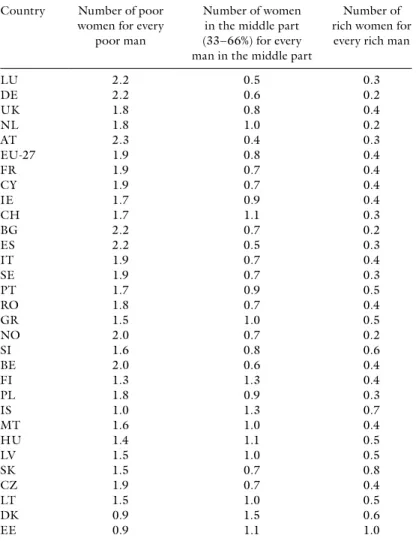

3 Gender Gaps in Pensions in Europe 35

4 The Gender Pension Gap in Europe: Toward

Understanding Diversity 55

5 Benchmarking the Analysis: Europe, Israel, and

the United States 81

6 Pension Systems and Pension Disparities 109 7 His and Her Pensions: Intra-Household Imbalances

in Old Age 123

8 Looking Ahead: Pension Reforms and Inequality

in Old Age 135 Appendix 1 151 Appendix 2 157 Appendix 3 159 Notes 165 References 175 Index 183

Ack now l edgmen ts

D

ata from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Situations (EU-SILC) © European Union, 1995–2014.This publication uses data from SHARE wave 4 release 1.1.1, as of March 28, 2013 (DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w4.111) or SHARE wave 1 and 2 release 2.6.0, as of November 29, 2013 (DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w1.260 and 10.6103/SHARE.w2.260) or SHARELIFE release 1, as of November 24, 2010 (DOI: 10.6103/ SHARE.w3.100). The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through the 5th Framework Programme (project QLK6-CT-2001–00360 in the thematic pro-gramme Quality of Life), through the 6th Framework Propro-gramme (projects SHARE-I3, RII-CT-2006–062193, COMPARE, CIT5- CT-2005–028857, and SHARELIFE, CIT4-CT-2006–028812) and through the 7th Framework Programme (SHARE-PREP, N° 211909, SHARE-LEAP, N° 227822 and SHARE M4, N° 261982). Additional funding from the US National Institute on Aging (U01 AG09740–13S2, P01 AG005842, P01 AG08291, P30 AG12815, R21 AG025169, Y1-AG-4553–01, IAG BSR06–11 and OGHA 04–064) and the German Ministry of Education and Research as well as from various national sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org for a full list of funding institutions).

EU Coun t r ies’ A bbr ev i at ions

AT Austria BE Belgium BG Bulgaria CY Cyprus CZ Czech Republic DE Germany DK Denmark EE Estonia EL Greece ES Spain FI Finland FR France HU Hungary IE Ireland IT Italy LT Lithuania LU Luxembourg LV Latvia MT Malta NL Netherland PL Poland PT Portugal RO Romania SE Sweden SI Slovenia SK Slovakia UK United Kingdom1

Women, Ol d Age, a nd

Independence: Wh y In v est igat e

Yet A not her Gender Ga p?

Introduction

Ageing as a challenge for all societies has been known to exist for more than a generation; the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) produced an authorita-tive study warning of population ageing in 1980 (OECD, 1981). Awareness of impending changes spread, first to the policy com-munity, then to policymakers; it thus motivated a number of reforms through the world, adjusting institutions to cope with a changing reality.

As time proceeds, what first appeared as a theoretical challenge to society as a whole increasingly has visible implications for indi-vidual men and women in advanced societies. Whether directly, as more people are entering retirement, or indirectly, as ageing-driven reforms are spreading, the process of ageing is a potent source of change for everyday lives. Some of these changes were planned for, others were anticipated, yet others may come as surprises.

This book tries to catalog one such category of changes, those affecting the relative position and economic independence of men and women in later life. It does so by focusing on the most impor-tant determinant of economic independence, the existence of inde-pendent means. This, for the vast majority of women in Western societies, means access to a decent pension. The book complements our knowledge of the field of gender inequalities in work—the gen-der pay and earnings gaps—by looking at what happens to inequali-ties after retirement. We know that the world of work has been growing more equal between genders, in some, though not in all,

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 2

respects. Will this progress mean that the battle for equality in later life has been already won? Is it simply a case of waiting for the gains in equality during the period of work to percolate through to later life? Is the pension system, in other words, a neutral filter reflecting the situation in employment, albeit with a lag?

It is possible to point to features of pension systems that can either reinforce inequalities or, alternatively, correct them. This book takes an agnostic attitude on this question. Having posed the question, it proceeds to describe and compare the situation regarding gender-based pension inequality using comparable information for a wide range of advanced societies. In this con-text, the book places the primary focus on the countries of the European Union (EU), treating their experience as a kind of gen-der policy laboratory.

So, the European focus is not simply parochialism. The diver-sity of experience between European countries, the nature of social policy, and the direction and speed of pension and other reforms mean that the experience of different EU countries span a wide range of experience. This can serve to illustrate the differing impacts that are likely to face any advanced country meeting the challenge of ageing. The common membership of the EU ensures the existence of regular and comparable data for all countries; the fact that all EU members coordinate their policy efforts to meet the ageing challenge implies that this work can plug in and take advantage of an active policy dialogue.

The EU actual experience, as measured by the yardstick of sta-tistical indicators used in this book, can then be usefully bench-marked and compared with experience in other countries. This is done by surveying published work in other advanced countries, as well as direct comparisons in two cases (Israel and the United States) where similarity of data allows construction of the same indicators we derived for the EU. In this way, by starting out in Europe and spreading the inquiry gradually wider, we are able to generalize about the challenges faced by advanced societies more generally.

Much of the literature on ageing entails looking at the macro challenge to societies of impending changes. Our own work, in contrast, treats ageing as a fact of everyday life and sees as a micro problem affecting individuals. Whereas the collective challenges of ageing are similar in nature across all countries, the response

Wom e n, Ol d Age , a n d I n de pe n de nc e 3

to ageing as affecting individuals is likely to be far more varied— reflecting differences in history, institutions, preferences, and policies. Public policy, in order to be effective, needs to under-stand the complexity of responses as regards gender, while not losing sight of the macro challenges. The plea made in the final chapter is that public policy should be concerned with both dimen-sions at the same time.

The Need for Gender Vigilance for

Older People

Simone de Beauvoir, writing in the 1960s in The Coming of Age (1970), was conscious of a pervasive gender dimension in the way society treated old age:

What we have here is a man’s problem . . . When there is speculation upon the subject (of old age) it is considered primarily in terms of men. In the first place because it is they who express themselves in laws, books and legends. (de Beauvoir, 1996, p. 89)

Things need not necessarily be so bleak. At a later point in the same book, she notes a potential for righting gender imbalances:

For women, the last age is a liberation . . . Now at last they can look after themselves. (p. 489)

A generation later, policy is called upon to diagnose and correct the problems created by human institutions and social processes in order to realize the potential for independence that de Beauvoir sensed existed.

An obstacle that existed then is still present: older women are taken for granted, while in many countries they are insufficiently represented in decision-making fora. Their well-being and inde-pendence are the outcome of complex forces: older women and men are affected by long-term social changes like population age-ing; they are the first group affected by the cumulative impact of 20 years of gradual institutional reform in pension systems and elsewhere; in the current economic and fiscal crisis, they are fre-quently one of the groups most immediately affected by fiscal retrenchment. At the same time, today’s older women witnessed

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 4

in their working lifetime a major transformation in the roles played by women in economy and society, a transformation that took place at different speeds in different countries and is yet to be completed.

Pension systems have changed considerably over the last 20 years, and are changing still. Older women have lived and worked in one system and will collect their pensions when that system will be considerably different. This process is in opera-tion across the world, yet had started at different times and has proceeded at different speeds. Countries are faced with com-mon problems, but choose to deal with them in ways that are affected by their own history, institutions, and preferences. In this way, older women’s pensions across the world carry simulta-neously echoes of past disadvantage and premonitions of future vulnerability. Comparing the situation of older women between countries, especially if the ostensive objectives of these countries are comparable, would allow to make inferences about the policy environment and the reform toolbox. The diversity contained in the Member States of the EU can thus be seen as a microcosm for the dilemmas faced by all advanced societies—a kind of labora-tory where ideas and inferences can be tested.

These reasons, taken collectively, imply that it is important to know the extent and location of gender differences in pensions. Perhaps more significantly, in a field which is complex and is affected by numerous influences, it is important to track changes over time. If this can be attained, problems might be spotted early on and solutions sought and implemented in a timely fashion.

This book suggests that policy would benefit if a gender gap in pensions (GGP henceforth) indicator were available on a regular basis. It defines such an indicator, which can be easily produced across the EU on an annual basis and extended elsewhere with relative ease. The book investigates its properties and uses it to characterize the dimensions of the problem for different groups of the population and different institutional settings; it points the way to further work. A key insight is that the nature of the prob-lem and our understanding of it are such that it is not sufficient to produce a one-off research report calculating the indicator at a point in time. On the contrary, an indicator on gender imbalances in pension ought to be available on an annual basis to guide policy and orient public discussion.

Wom e n, Ol d Age , a n d I n de pe n de nc e 5

Why Monitor Gender Differences

in Pensions?

Pensions are the single most important component of older peo-ple’s income. In contrast to other components, such as return from savings and income from property or rents, which accrue to the whole household and cannot usually be separately attributed to a particular member of the household, pensions are paid to individ-uals. They thus are an important determinant of economic indepen-dence of their beneficiaries—the capacity of an individual to lead an independent life and to take decisions for him/herself. In this way, differences in pension rights between women and men form the foundation of gender differences between the sexes in later life, as regards each person’s capacity for individual choice.

The distinction between economic welfare and economic inde-pendence is important to make and to understand. Economic wel-fare, the access to resources and capacity to well-being, depends on a wider set of income sources, which accrue to the household (Atkinson, 1989; Deaton and Muellbauer, 1980). In order to study welfare, all income entering a household is aggregated, and then apportioned between the members of that household. Given that a household, by definition, is a social unit where consump-tion is shared among its members, total household income is fre-quently and by necessity assumed to be distributed equally among its members. In social surveys, which are used to gauge economic well-being, this means that income of men and women living as a couple is equal by construction.1 Indicators, such as poverty

rates, which rely on household income, constrain in this way the poverty status of men and women living as couples to be iden-tical. Differences in poverty rates by gender thus essentially rely on comparisons between single member households: people who never married, divorced individuals, widows, and widowers. Due to this fact, gender differences in access to resources are almost certainly severely underestimated in any measure which relies on household income. Should our interest lie in the related, but con-ceptually distinct, issue of relative independence between genders, this shortcoming is even more distorting.

For people of working age, this train of thought leads natu-rally to a focus on differences in employment remuneration— most frequently encapsulated by some measure of pay or earnings gap.2 In the case of women, this is essentially an achievement gap,

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 6

reflecting the fact that women, in many contexts, may be under-paid, undervalued, overworked across the board; their responsi-bility for unpaid work in the family leads to underrepresentation in the paid labor market. Once people have left the labor market, the analog of pay or earnings is the source of income that replaces them, that is, pensions. An indicator of a pension gap would in this way be a natural complement, almost a sequel, to an interest in gender earnings gaps. Given that many pensions systems are designed to reflect employment experience, one would expect that pensions would reflect the cumulated disadvantages of a lifetime’s involvement in a gender-biased labor market. The further back in time one goes (and hence the older the pension recipient), the more marked one would expect this effect to be.

However, pensions do not simply reflect labor market experi-ences in a neutral way. Systems which rely on the accumulation and investment of contributions may actually exacerbate inequalities in employment remuneration. In contrast, as the largest single item of social protection expenditure, they are in principle called to correct to some degree what are perceived as imbalances (or even injustices) of the labor market. For this reason, the possibilities of intervening to correct gender imbalances are much greater in pensions than in earnings. An intervention requires information. A focus on gen-der differences in pensions would be an invaluable addition to the policy toolbox.

Those two arguments, to complement pay gender gaps and to orient public pension decisions, are sufficient to justify a policy interest in pension differences between men and women. Why should that interest entail following those differences in regular time intervals? In other words, why should public bodies or orga-nizations such as the EU consider adding a new pension gap indi-cator to the set of indiindi-cators they publish every year?

An answer to the question of “why an annual indicator?” can be sought in the complexity of influences that combine to pro-duce the pension gender effects that will appear every year. These influences can interact mutually or with other features and can frequently lead to unforeseen outcomes, possibly even some “col-lateral damage.” The structure of pensions—and hence gender-based differences—is influenced by three sets of factors:

First are very long-term structural changes, operating like tec-tonic changes to transform the pension environment. Ageing and

Wom e n, Ol d Age , a n d I n de pe n de nc e 7

demography are the most well known of these differences: older women are increasing in number; their state of health is changing while in comparison with earlier periods they have fewer children and social ties are looser. The anticipation of future acceleration of ageing may already have effects on today’s older people, as policy adjusts with a lead.3 Similar in their effects to ageing, are echo

effects of past employment patterns. Today’s pensions may reflect yesterday’s employment picture. The pace of women’s emancipation in the labor market has proceeded at different speeds in different parts of Europe (Jaumotte, 2003; Lyberaki et al., 2013; Pissarides et al., 2005), with the North typically more advanced than the South. The older cohorts may be more influenced by past gender imbalances; younger pensioners may already show the effects of nontraditional modes of working (part-time, contract work, etc.). Finally, social norms have been altering aspects that affect pen-sions: the incidence of divorce, the prevalence of widowhood, and the probability of cohabitation between generations.

Second, today’s pensions are intimately affected by the extent and spread of institutional change, chiefly pension reform.4

Pension reforms have been an ongoing project in Europe since the 1990s. They are motivated by influences particular to pensions, such as the need to prepare for the long-term fiscal challenge of ageing, in some cases transforming the pension picture completely (Bonoli and Shinkawa, 2005). Given that public pensions form an important part of the functions of government, pension provi-sion has also been affected by more general tendencies of public sector reform. New pension structures lay stress on cooperation with private initiative (the “multi-pillar pension systems”), while there is an increasing emphasis on individual responsibility and a consequent tendency to direct entitlements to individuals rather than households.

However, in most cases, reforms influence the flow of people entering retirement, and, hence, take a long time to percolate through all retirees. Insofar as one can generalize, today’s retirees are affected by the general climate of retrenchment. Given that in many countries pension reforms have been under way for almost two decades, they are often covered by transitional arrangements designed to smooth the effects of those reforms and addressed toward those relatively close to retirement.5 This phenomenon is

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 8

systems mature, there will be an increasing number of individuals whose pensions will be marked by the characteristics of the new systems, and who will be vulnerable to new kinds of pension risks, probably linked to the operation of the new system. Indeed, in those countries where reforms took place first (e.g., Holland, United Kingdom, and Switzerland), those effects should already be visible.

The two most salient directions that are likely to impact on gen-der issues are: First, the switch in emphasis from first pillar pensions (provided by the State and usually based on societal solidarity and pay-as-you-go financing) to second pillar pensions (i.e., provided collectively based on occupational solidarity, and prefunded). This switch is frequently (though not always) combined with a change in the type of pensions from defined-benefit (DB), final salary schemes to defined contribution schemes (Mackenzie, 2010). The overall effect tends to be an increase in individual responsibility in the form of a closer link between contributions and benefits7 and

hence an overall reduction in solidarity of the system. Indeed, in the United States, this trend has been termed “the privatization of risk” (Orenstein, 2009), in the sense that it transfers risk from the employer and worker to the beneficiary. The second reform direction is the emphasis on working longer, which is a key message in “Europe 2020.”8 Though the long-term rationale of this

direc-tion is unassailable, there may be side effects in the medium and short terms that must be guarded against: disincentives for early retirement may lead to lower incomes for those with little choice (e.g., due to inability to work later owing to caring responsibili-ties). While the focus is (rightly) on the supply of labor (i.e., on incentives to work longer), employer prejudice and discrimination in training may keep demand for older workers low.9

The final set of factors shaping pensions are short-term pres-sures, usually connected with the current economic crisis. These pressures vary from country to country but could lead to impor-tant (and hard-to-predict) swings in gender effects. For example, greater insecurity in the labor market increases the relative attrac-tiveness of state-provided DB pensions; in this way, fiscal problems are exacerbated. Second pillar pensions have been hit hard by the collapse of asset values.10 The sovereign debt crisis led to numerous

cuts of pension in payment, making a mockery of the notion of “DBs” and fueling pensioner insecurity.11 In a cash shortage, first

Wom e n, Ol d Age , a n d I n de pe n de nc e 9

the direct control of the public sector; pensioners as a group are vulnerable to public finance pressures.

Recapitulating, older women pensioners may be, as a group, “stuck in the middle.” They have lived and worked under one s ystem—which frequently implicitly presupposed a “male breadwin-ner model”; they will in many cases receive benefits under another. Where their entitlements are transitional (“grandfathered”), they depend on government assurances given at the time of the original reform (the urgency of which many years later may be forgotten). They are, thus, not protected by the internal operational logic of the system, whether new or old. Women may be more at risk than men: their rights on social insurance are often “derived rights” (survivors’ pensions, married people’s supplements); in those sys-tems where a second pillar is taking hold, women are more likely to rely on state systems, or to be more affected by gaps in contri-butions and broken careers; finally, in many countries, they persist in the role of carers (for children or aged parents) even as unpaid work is receiving less recognition.

Women in particular may be vulnerable due to four factors: 1. Echoes of past problems—women may have fewer pension

con-tributions. This may be due to broken careers, low pay, segrega-tion, past discriminasegrega-tion, working informally.

2. Premonitions of future problems. Tighter linking to contribu-tions, though desirable in itself, may exacerbate current dis-advantages faced by women. Types of work such as part time may lead to lower rights in future; multi-pillar systems could compound disadvantages by introducing effects magnifying inequalities.

3. Problems where institutional change may lag behind social change (e.g., social insurance treatment of divorce, widowhood).

4. Women may in practice be more vulnerable to crisis-induced changes. If women are worse off to begin with, they may be more vulnerable to a sudden deterioration. Despite protesta-tions to the contrary, “male breadwinners” or “heads of house-holds” may implicitly be given priority in crisis responses. Current pensions received will, thus, at any one time reflect both long-term factors operating slowly and other influences due to the conjuncture. Some effects may be policy driven, while

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 10

others may be due to individual choice. The types of policy which will affect pensions of the two genders may be not only sys-temic features but also decisions taken in a shorter time frame, sometimes in contexts not directly related to pensions, such as the macroeconomy or public finances. In this type of situation, it is important that policymakers must be made aware of gen-der effects, so that the source of the imbalance can be identified and—if possible—corrected.

The EU, as a supranational organization, is built around the notion of subsidiarity; in the layers of authority starting from the local onto national and then Union-wide levels, decisions are taken at that level closer to the individual. Or, to look at matters from the opposite direction, decisions assigned to the EU level need to demonstrate substantial value added relative to taking them at the national level. Equal pay and gender balance are part of EU’s “hard law,” in the sense that they can influence the operation of the single market and competitiveness. The EU has therefore taken a lead in promoting gender balance across the EU.

The case of ageing is somewhat different. Social policy, partly due to the very different institutional starting points, has always been a prerogative of the nation-states.12 Nevertheless, given its

salience in economic, fiscal, and labor affairs, there has always been a case of coordinating social policy. Once social policy was co-opted in the competitiveness narrative as a factor allowing greater competitiveness (encapsulated in the phrase “social pro-tection as a factor of production”), then the importance of coor-dination became all the more obvious. Ageing as a cross-cutting issue was brought into the European ambit in the early 2000s (by the Gothenburg summit). The coordination of (public) pension policy in the context of ageing was assigned to the Open Method of Coordination (Papadimitriou and Copeland, 2012), used as an instrument of policy dialogue and to encourage consistent reforms in the Member States.

As the EU in the past had taken a lead both on gender balance and on ageing populations, it is reasonable to expect that it should follow on with possible side effects of the one area of activity impinging on another. Gender aspects of pensions are the intersec-tion of two already busy areas of policy; bringing pension gender balance to the attention of policymakers is likely to elicit a policy dialogue of relevance to all industrial countries.

Wom e n, Ol d Age , a n d I n de pe n de nc e 11

The Sustainability-Adequacy

Policy Conundrum

There has been concern that demographic changes necessitate major readjustments to pension systems for at least 30 years (e.g., OECD 1981, 1988). The emphasis up to the 1990s was on the need to safeguard sustainability of the pension systems. When the EU became formally involved (as a result of the Gothenburg and Stockholm summits in 2001),13 it brought into the limelight

the idea of adequacy, which can be understood as the extent to which pension systems fulfill their social policy functions. The two concepts should be complementary and inseparable, in the sense that they comprise a trade-off: sustainability can always be satisfied by sacrificing adequacy, or vice versa. The task for policy is to seek changes that do as well as possible in both dimensions at the same time.

Adequacy in the field of pensions means two different things: first, avoidance of low income and poverty at old age, which it shares with social inclusion policy. Second, ensuring smoothing of income at different stages in the life cycle; retirement from employment should not lead to sharp falls in financial well-being. Those two objectives are, to some extent, antithetical. Indeed, “Beveridge-type” social protection systems (based on citizenship rights) traditionally have given emphasis toward the first objec-tive. “Bismarck-type” continental systems organized around social insurance use income smoothing as their starting point.14

However, though the two systems’ origins may differ, they evolved in converging directions, with the result that it is now possible to talk of a “European social model.” This model has common objectives, which can, perhaps, be pursued by different instruments. Indeed, this recognition is the essence of the Open Method of Coordination, applied in the field of pensions since 2001.15 Concern of researchers and policy commentators in the

United States and other countries mirrors this schema, though fragmentation of areas of responsibility leads to separate treatment of public and private pensions. The EU discussion is thus useful in bringing all areas of concern to bear in a single policy document.

The dimension of gender enters through this twofold frame-work. Nevertheless, the fact that the discussion was always placed squarely within the area of social policy implied that features such as greater longevity for women were not allowed into the

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 12

discussion. As a result, European discussion of equity issues in pensions sidesteps the fact that women live longer;16 thus, unisex

actuarial factors are used in all new systems.17

It was clear all along that much of the sustainability adjustment had a gender dimension: women’s retirement ages and labor force participation were envisaged as adjusting the most. At the same time, pension reforms frequently did away with some g ender-specific aspects of pension systems which were originally justified as compensating women for non-pension obstacles. Similarly, fea-tures of new systems could interact with existing gender disad-vantages to produce new kinds of inequities, even as provisions that perpetuated disadvantage were gradually done away with.18

Finally, many of the principles running through reforms could, as side effects, lead to lower entitlements for women: closer linking of contributions to entitlements cannot avoid penalizing periods out of the labor force, unless some mitigation is designed. These loom-ing threats can be well illustrated by work profilloom-ing hypothetical career structures and computing (“synthetic”) replacement rates for people who fit those profiles; the Indicators Subgroup (ISG) of the Social Protection Committee (SPC) has produced such results,19 as has the OECD. The work of the ISG is a clear warning

sign, that, should behavior remain unchanged, many new equity issues affecting gender could appear in future years.

Long-term strategic policy in the EU operates on the basis of key strategy statements which orient its actions. The “Lisbon strat-egy” was decided during the Portuguese presidency of 2000 and was supposed to orient policy and reforms in the period to 2010 (Papadimitriou and Copeland, 2012). The successor of the Lisbon strategy is known as the Europe 2020 strategy20 (Armstrong,

2012). That document gives a clear signal that pension reforms and working longer will have pride of place in the overall attempt toward “smart, sustainable and inclusive growth.” In this context, though, policy formation is facing a conundrum, which is espe-cially sharp in the field of gender.

This conundrum facing all policy toward gender and ageing is illustrated well by two key documents, both published by the EU in 2012. The 2012 Ageing Report21 notes that the reforms

of the last few years have resulted in the outlook for sustainabil-ity being much improved in comparison with the 2009 Report. The 2012 Adequacy Report22 is more circumspect, noting that

Wom e n, Ol d Age , a n d I n de pe n de nc e 13

“analysis of the change in replacement rates . . . demonstrates that greater sustainability . . . has been achieved through reductions in future adequacy” (p. 9).23 The same report goes on to say that

“an important part of the adequacy challenge is gender specific.” In other words, pension reforms could, if people’s behavior does not change, pose threats to gender equity among the older popu-lation. Avoiding this is a key challenge for the EU; this holds equally for all advanced countries.

Much of the Adequacy Report discusses this challenge. It examines statistical indications of today’s situation and assesses the knowledge gaps to be filled by future work. Indeed, it may be said that the Adequacy Report, through a different route and from a different starting point, has arrived at the same conclusion that this book has reached: ageing policy cannot do without careful and regular monitoring of the gender pension gap.

Outline of the Book

Chapter 2 introduces the an intuitive concept of gender gap in pensions indicator, constructed to be a kind of later-life sequel to the pay, earnings, and participation gaps familiar from analy-ses of younger men and women. It discusanaly-ses how a pension gap may appear as the interplay between the cumulative inequality of working life and the operation of the pension system. The points of difference and similarity between the working life and retire-ment measures of gender inequality are compared and contrasted. Chapter 3 gets to work by examining the broad outlines of the gender gap in pensions indicator in Europe; its value in 2011, the situation regarding women with no access to pensions, differences between people of different age classes, and trends over time. The next chapter presses on with European pension gaps, describing and explaining their diversity across the continent: by education and marital status, according to different career patterns, its rela-tionship to the overall distribution of income. Chapter 5 spreads the net wider by attempting to benchmark and to generalize the key European results. It examines estimates based on administra-tive data for Europe and published studies from elsewhere, giving particular emphasis on the United States. In two cases, the United States and Israel, where there exist data directly comparable to the European survey we compute direct analogs. The benchmarking

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 14

exercise points to the international relevance of the European results. The US results can be said to amplify the warning of dan-gers ahead. Chapter 6 examines to what extent the European data can be said to reflect directly typologies of welfare state. The con-clusion is that pensions systems introduce idiosyncrasies that pre-clude easy generalizations. One such complication of importance for policy is the focus of the next chapter—difference s in pen-sions inside the household between spouses—the intra-household gap. The conclusion that transpires is that there may be a conflict between greater independence on the one hand and poverty pre-vention on the other. Finally, the concluding chapter provides an overview of results and discusses what they mean about the flavor of challenges yet to come.

2

Concep ts a nd L i t er at ur e

Introduction

This chapter is devoted to the definition of concepts, the construc-tion of indicators, and the choice of data. The idea is to seek the simplest way to bridge the gap between the macro representation of ageing indicators and the micro experience of individuals, in this case to highlight differences between men and women. Given the decision to survey experience across countries, a further matter of importance is ensuring that the data used can be compared: that they have similar meaning and coverage. A further issue is that the data and the indicators must be able to feed into policy discussion by shedding light on social processes in a transparent manner.

We approach the issues in a slightly unorthodox fashion: we first introduce and outline the definition of indicators and indicate the data to be used. We then take a step back and examine litera-ture on gender inequalities on pension, which, in a sense, is what gives life to our indicators. We thus set the stage for the analysis of our own indicators in chapters 3 and 4.

A Gender Gap in Pensions Indicator

An indicator is a construct halfway between the worlds of policy discussion and that of data. It provides a bridge of understanding that summarizes a picture of the world that statistics give, but in a manner that can inform policy and give meaning to public discus-sion. Atkinson et al. (2002) discuss the general issue in a report commissioned by the EU to suggest indicators in the field of pov-erty and social inclusion. Theirs was an example of a highly charged area in emotional terms, poverty. In that case, there coexisted strong (frequently value-informed) presuppositions which needed to be translated to yield indicators with a precise quantitative

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 16

meaning, while still doing justice to the notions these indicators were attempting to portray. Their report deals extensively with the characteristics a good indicator should have. Following their approach, an indicator tracking gender imbalances in the field of pensions should:

be easily understood,

● ●

be available on an annual basis,

● ●

be available and comparable across countries, and

● ●

should complement existing indicators in current use. In the

● ●

advanced economies this would mean indicators of the risk of poverty but also gender pay and earnings gaps.

Given the above, in the European context the only realistic source of data is the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) (Eurostat, 2011; Verma and Betti, 2006). This is a questionnaire-based survey, which draws a random sample cov-ering the entire population and is currently conducted annually in all 28 EU member states.1 Considerable effort is expended to

standardize answer categories to make them internationally com-parable. The last available data are based on the survey conducted in 2011; given that the question posed to respondents refers to the past year, the situation reflected in the data is that pertaining to 2010. The same survey is used to construct other EU structural indicators, most notably those connected with social inclusion and the risk of poverty; its properties, advantages and drawbacks, are well understood. As the survey has been conducted with only minor changes since 2005, SILC information is also comparable over time.

EU-SILC asks households detailed questions about income sources of all their members, whether from employment, from property or social transfers.2 Social transfers are defined in such

a way as to include under the same heading both first pillar (state pensions) and second pillar (occupational pensions). The two pil-lars cannot be distinguished (reflecting a judgment that at least in some systems the demarcation between the two may rely on fine distinctions), a matter of some importance in the current inves-tigation. In contrast, individually negotiated pension packages (the third pillar) are distinguished. A feature of EU-SILC that is problematic is that (in most countries) survivors’ pensions paid

C onc e p ts a n d L i t e r at u r e 17

to individuals older than 65 are classified as “old age protection” and not separately identified.3 In situations such as this, where

there are problems of comparability between countries, the sum of three variables (in this case, “pensions”) may be more reliable and meaningful than each component taken separately. These two issues, the inability to distinguish survivors’ pensions and second pillar pensions, may be thought as “blind spots” of EU-SILC in the context of gender gap in pensions analysis.

EU-SILC is a survey of the population irrespective of age; moreover, it probes especially in the areas linked to economic and financial well-being—that is, “income and living conditions.” For an older population, there exist other questions and areas of enquiry, such as health care, and social relations, which acquire greater importance. In order to delve in greater detail in particu-lar issues or to investigate issues related to the EU-SILC “blind spots,” it is possible to draw data from another survey of European countries. This is the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), an interdisciplinary survey covering eco-nomic well-being, health, (physical, mental, and health care), and social relations.4 Though it is of the nature of sample surveys that

they cannot be absolutely comparable, being able to draw on an alternative survey can be thought of as a check on key findings in EU-SILC. Equally, the existence of more detailed information on items such as employment histories can shed light on causal mechanisms that may be obscured in EU-SILC. The first two waves of SHARE were undertaken in 2004 and 2007, while the third wave (SHARELIFE) was devoted to extracting retrospective information for respondents’ entire life from childhood. There was a fourth wave in 2011, while the fifth wave was collected in 2013, data for which are at varying degrees of readiness. SHARE wave 2 will be used to supplement the picture derived from EU-SILC.

When we focus on older populations, we must be aware of a further blind spot—the exclusion of people living in old people’s homes, hospitals and other collective habitations—that is, people not living in normal households, which is the sampling unit in all s urveys.5 The proportion of the older population living in this type

of accommodation has a strong gender dimension, while it also has a very notable North–South gradient. Moreover, one may expect that the sampling rate of those parts of the elderly population who are infirm, bedridden, or have fading cognitive abilities may well

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 18

be lower.6 This is an argument for supplementing EU-SILC data

with other surveys designed for an older population, which try to accommodate these issues to a greater extent.

A matter of some importance is the decision of whom to include in the definition of “pensioner.” This has two aspects, which are explained below.

First, individuals themselves decide when to leave work and to enter retirement. They decide whether to apply for a pension as a conscious decision, depending on a number of features both of their personal circumstances, the parameters and regulations of the pensions system in place (e.g., minimum retirement ages), and ultimately whether they prefer to be pensioners rather than to carry on working.7 The transition from work to retirement is

a very complex process; the kinds of issues that enter into it are largely distinct from the issues that motivate the search for a pen-sion gap indicator. In order to abstract from these complications and to produce an indicator that retains the feature of simplicity and ease of understanding, we investigate a homogeneous group of people. That group is defined in such a way that the transition from work to retirement is complete, and whose pensions have settled into the relationship with other income that will character-ize the rest of their retirement. To achieve this, the simplest course is to focus on the group of people over 65. In all advanced countries, the transition to retirement is all but complete;8 in consequence,

the relationship between pensions and other incomes, as well as, most crucially, gender differences in pensions have settled into their long-term values.9

During the course of the analysis, age will be subdivided fur-ther (into “the younger old” 65–80, and “the oldest old” 80+). Indicative results will also be presented for the younger retirees (50–65) (Section 3.6). In this way, the effect of excluding large numbers of pensioners in those countries with a lower retirement age can become apparent. Furthermore, the use of 65 as a cutoff age also serves to underline the concern for the elderly; that age is the conventional statistical start for “old age” and will thus allow the indicator to be harmonized with a large number of other works in the area. The older group aged 80+ is, in some senses, prob-lematic: Selection problems begin to matter, as in some countries a large proportion of individuals go into old age homes, while international differences in life expectancy also affect relative size

C onc e p ts a n d L i t e r at u r e 19

of the group between countries. In a similar vein, we shall see that survivors’ pensions can complicate the picture for the over-80s considerably, while a greater time would separate current pensions from original value when first issued. For some purposes con-nected with policy, therefore, it could make sense to separate what could be thought of as the “central pension gap”—that is, that affecting the group aged between 65 and 80—from the “senior gap” or outside gap of the over-80s. Pension gaps of individuals in the central age group can be expected to be closer related to fea-tures of the pension system as it is currently operating and to offer a closer guide to policy.

The second important issue is also related to the definition of who is a pensioner. The definition used here is “any person who appears to be drawing a pension as his/her own income,” that is, individuals with nonzero values of pensions.10 This excludes from

the definition individuals who are not themselves beneficiaries of pensions, and whose pension income is zero.11 The definition of

who is a pensioner is thus sensitive to the definition of what is a pension. Should Eurostat define in EU-SILC small social ben-efits given to older people in, say, recognition of child rearing, as “pensions” then our definition will include individuals collecting them as “pensioners”;12 they will unavoidably enter the

calcula-tion on an equal standing with age pensioners whose pension is substituting at least for minimum resources. If (as is likely) these types of pensions are more common among women, this would introduce a considerable upward bias to pension gap estimates. However, this problem may be seen as an example of the statistical tools improving as more use is made of them.13

Thus, a pension system would be defined by two indicators: one measuring gender pension differences for those with a pension and another indicator depending on system coverage—that is, the gen-der differences for those people over 65 who have no pension. It should be noted that the exact parallel exists in the case of people of working age: gender analysts are used to talking separately of a participation gap (i.e., how many more women rather than men are working for pay) and an earnings (or pay) gap; the latter looks at earnings of those who are working and compares women and men.

The Gender Gap in Pensions is computed in the simplest possible way: it is one minus women’s average pension income divided by men’s

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 20

average pension income. To express it as a percentage this ratio is mul-tiplied by 100. It is the percentage by which women’s average pension is lower than men’s, or by how much women are lagging behind men. Thus, in parallel with earnings gaps we define two linked indicators: 1. The coverage gap—that is, the extent to which more women

than men do not have access to the pension system (in the sense of having zero pension income—as that in defined in EU-SILC).

2. The pensioners’ pension gap—or else “the” pension gap, that is, the difference in pensions excluding zero pensions. This mea-sures how the pension system treats “its beneficiaries,” that is, the indicator excludes those that have no active links with p ensions.14 It is thus what data produced by pension providers

themselves, that is, administrative data, would invariably cover by construction. This definition would thus match statistics pro-duced by pension providers, or any other kind of administrative data (e.g., compilations of pension fund data).

If we include in the pension average calculation individuals with zero income, we arrive at an indicator which combines the two above—which can be called the “elderly pension gap,” in the sense that it includes in one indicator all people over 65.

Thus, the analysis will use the pensioners’ pension gap and the coverage gap as its “headline indicators”; it will, nonetheless, investigate how these two indicators combine in the elderly gap.

Clearly, in surveys of individuals of a comparable structure to EU-SILC, such as SHARE or the US Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), we can define a pension gap and coverage indica-tors in equivalent ways. (Details on the use of SHARE as a source of information as well as the description of the pension variables in SHARE wave data are provided in the Appendix to this chapter, as well as the corresponding information on HRS.)

The Question of Administrative Data

In the Gender Gap in Pensions analysis at the European level, a key consideration is that of comparability—that is, the numbers produced have to mean the same thing for all member states. This,

C onc e p ts a n d L i t e r at u r e 21

in a survey coordinated on a European level, such as EU-SILC, is ensured by asking a common set of questions and ensuring the definitions and concepts can encompass the heterogeneity that is unavoidable in collecting data from 27 different jurisdictions. Comparability is not something that emerges automatically; it continuously improves with the use of data and with attempts to resolve the problems of interpretation that arise. Thus, the very fact of highlighting a particular area of data by using it will bring forth improvements in the survey information.

Yet it is inescapable that in each member state taken separately, the natural place to look for pension gender differences is from those organizations that disburse those pensions—that is, to use administrative data. For someone accustomed to the picture emerging from administrative data, the EU-SILC data may well be unfamiliar. It is thus important at the outset to understand why and in what directions administrative data may differ from survey information:

Administrative data would of necessity cover

●

● only those receiving

a pension (i.e., what we call the pensioners’ gender gap, rather than the elderly gender gap).

National pension systems are frequently fragmented—there may

● ●

be a multitude of pension providers and data may exist sepa-rately by occupational category. In multi-pillar systems, statistics for the pension total (equivalent to SILC which aggregates first and second pillar pensions) may be hard to get. The typical case is that statistics for the first pillar is far easier to obtain than that from the second;15 the latter are very hard to aggregate to

derive a national picture. Sometimes data for parts of the sys-tem (e.g., civil servants) are only available separately and are not aggregated.

Administrative data are frequently produced separately by types

● ●

of pension: old age, disability, and survivors may produce sepa-rate statistics.16 Pension providers naturally count legal claims,

which can be conceptualized as counting pension checks and not people. In the (not fanciful) case of someone entitled to two pensions, it is fully possible that that person will be counted twice; indeed, it is not unknown in pension statistics for the pensioner population to exceed the demographic population. This is sometimes corrected by conducting a periodic (in France

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 22

every four years, also in Germany) survey of activities of pension providers.

Administrative data would normally be available for all

pension-● ●

ers. These would include those under 65 who are excluded in our definition. Additionally, differences will be due to those excluded from the EU-SILC sampling frame—those living in old age homes, those not responding due to cognitive problems, and those resident abroad; on the other side will be beneficiaries of foreign systems, as well as cases of fraud.

Finally, administrative data have a key advantage of linking in

● ●

with macroeconomic and fiscal data, as it those aggregates that enter the public finances. Similarly, it is administrative data that are used for projections by actuaries and statisticians. Though it is possible to blow up individual-level survey data to the popula-tion macro aggregates, this is a process that is error-prone and approximate.

In order to highlight and illustrate the crucial distinction between administrative and survey data, this book will return to the issue in chapter 5 by contrasting EU-SILC findings to a mosaic of available administrative data from 11 European countries.

What Do We Know? An Impressionistic

Literature Review

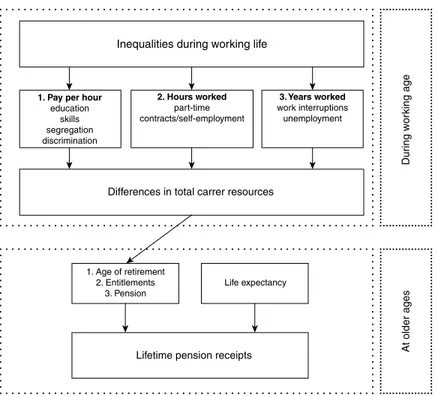

Figure 2.1 shows in diagrammatic form how pension gaps, that is, gender inequalities in later life, materialize. Inequities build up during individuals’ working life, in the form of differences in total career resources (panel A). These may cumulate differences in pay per hour (perhaps due to education, skills, but also segrega-tion and discriminasegrega-tion) with hours worked. Mothers and other women engaged in unpaid care work in the home find they can devote fewer hours to market-paid work, with the result that an earnings gap appears. This is cumulated by women frequently hav-ing to interrupt work for family responsibilities and unemployment by multiplying annual amounts by fewer years (though periods of military service or education which delay labor market entry may have similar effects).

Our interest is centered on panel B: annual pensions during retirement. Pensions are frequently a function of and are derived

C onc e p ts a n d L i t e r at u r e 23

from total career resources. However, pensions systems are not simply a neutral filter. They impact with the individual’s own choices, most frequently the age of retirement. A delay in retire-ment will frequently mean a higher pension; low pensions may, in this sense, be partly the result of the individual’s own choice. However, pension systems also introduce other features such as minima, maxima, subsidization of lower pensions, or other equal-izing factors from the realm of social policy. On the other hand, pension features rewarding thrift or risk taking (common in private and occupational pensions) may have the impact of exacerbating underlying working life inequalities.

However, one may go one step further and investigate the stock of pension outlays during an individual’s lifetime—the stock con-cept corresponding to the flow of annual pension payments. This would bring into the picture earlier retirement and differences in life expectancies, both importantly correlated to gender. “Lifetime pension receipts” is the appropriate concept to juxtapose to lifetime

Inequalities during working life

1. Pay per hour

education skills segregation discrimination

Differences in total carrer resources

Lifetime pension receipts

Dur in g w or king ag e At older ages 1. Age of retirement 2. Entitlements 3. Pension Life expectancy 2. Hours worked part-time contracts/self-employment 3. Years worked work interruptions unemployment

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 24

career resources. To investigate either would entail far more infor-mation than we currently possess, as we would need to delve into matters such as the difference between age groups and cohorts.

Conversely, annual gender gaps in pensions are the analog of pay and participation gaps. As flow concepts they can be the object of public policy interventions more readily like stock concepts than lifetime gaps. It is thus for practical, theoretical, and policy reasons that we focus on the pension gaps.

Gender Gaps as a Difference in Life Chances

The gender gap is one of the better-known aspects of empirical gender analysis. According to dictionary.com, gender gap (noun) is “the difference between women and men, especially as reflected in social, political, intellectual, cultural, or economic attainments or attitudes.” The gender gap is essentially an achievement gap. It focuses on inequalities in outcomes between men and women and usually places emphasis on wage rates, earnings, or other economic magnitudes.17

In more general terms, gender gaps could be taken to mean sys-tematic differences in access to resource or in life chances between men and women. In this way, the concept could be generalized in order to be applied to an older population, whose attachment to the labor market lies in the past but still may be a dominant influence on their economic well-being. Though this is a natural extension, the sequel of pay gaps, it has received far less attention, both theo-retical and empirical, than gender gaps more directly linked to the labor market. Does old age maintain inequalities, does it cumulate them and make them worse, or does it give a chance to redistribute and level life chances? (O’Rand and Henrietta, 1999).

From the Labor Market to Cumulative Gender Gaps

The gender gap in labor force participation has been eroding steadily over the past century, albeit with a different pace in dif-ferent countries and periods. The gender gap that attracts the most attention, however, is in earnings: here, though no steady trend is in operation, considerable progress has been recorded over time.18

C onc e p ts a n d L i t e r at u r e 25

As for the reasons accounting for the difference in earnings between men and women, economists tend to come up with observable and non-observable factors: education and shorter work experience belong to the first category, while discrimination19 to

the latter (e.g., Blau and Kahn, 2000; Smith and Ward, 1989).20

Finally, the unbalanced gender distribution in occupations (often called occupational segregation)21 supplies a further explanation

for women’s lower earnings, in the sense that they tend to popu-late lower-paid jobs (Bettio, 2008).

Evidence based on historical cross-section data provides a snap-shot of different economic outcomes in the labor market at a spe-cific point in time, as well as over time. In a more dynamic analysis focusing on the life pattern of the same individuals, the consecutive instances of different outcomes add up to an effect of cumulative disadvantage of women. Such a dynamic approach can follow one of the two following paths: either to utilize panel data sampling the same individuals over time or to assess the performance of different cohorts in the same phase in their life (say, reproductive ages 25 to 45 years). The latter approach has been used in order to evaluate the “maternity burden” on wages throughout the life course (Crittenden, 2001, for the United States; and Davies and Joshi, 1999; Davies, Joshi and Peronaci, 2000; Price 2006 for United Kingdom). On the investigation of interaction between the life course, pension system, and women’s incomes in later life in United Kingdom, West Germany, and the United States, Evandrou et al. (2009) and Sefton et al. (2013) conclude that dif-ferentials in income in later life by family history are greatest where work histories and retirement incomes are most strongly related (West Germany) than where weakest (in United Kingdom).

It is thus a well-documented fact that women are paid lower wages and tend to accumulate less income from (paid) work in the course of their working lives. There is a consensus that women’s role as the main carers at home largely explains their lower earn-ing record.22 This is the result of three main facts, present in all

national contexts, but to varying degrees:

First, women with family obligations participate less in the labor

market. Second, even when they participate, they tend to work for fewer hours and/or years. And third, they receive lower wages. (Davies, Joshi, and Peronaci, 2000) The combination of these three

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 26

stylized facts produces a snowball effect on women’s earnings and careers. Although it appears that the cumulative disadvantage over the life course has been eased in the late 1990s for women with high education characteristics, there is no recorded improvement for women with lower educational attainment (Davies and Joshi, 1999; Davies, Joshi, and Peronaci, 2000).

International comparisons reveal substantial differences in the cumulative earnings gap in Europe: Germany and United Kingdom show similar intensity in the gap, while France and Sweden display lower cumulative earnings gap (Davies and Joshi, 1994). In a more recent attempt to capture international varia-tions, Sigle-Rushton and Waldfogel (2007) utilized data from the Luxembourg Incomes Study in order to compare the cumulative earnings gap in eight countries.

From the Labor Market to the Gender Gap in Pensions

In a special issue on gender and ageing, Folbre et al. (2005) note “Although women are a majority among the elderly, little is heard about gender differences in economic resources” (p. 3). Fifteen years earlier, Hurd 1990 noted, “The great majority of research on retirement has been the retirement of single men and husbands.”

Even and Macpherson (2004), surveying how the US Gender Gap in Pensions evolved over the last 30 years, note what is the key question still to be answered. During that time there were dramatic improvements in gender balance in the labor market. Yet the gender gap in median incomes of the older population “has been stagnant over the past fifty years. The female–male ratio of median incomes in the population aged 65 and over was 0.61 in 1950 and fell only slightly to 0.59 in 1994” (p. 182). They explain this stagnation through countervailing institutional change in pension policy (extending the critical period for pension calcula-tion), as well as selection effects,23 chiefly to do with second pillar

pensions.

Tracking the Gender Gap in Pensions outside the United States has not been attempted in a systematic manner in a cross section of countries, in the way that has happened to pay and earnings gaps (as in, say, Olivetti and Petrongolo, 2008). There have been a number of studies of individual countries, usually focusing on

C onc e p ts a n d L i t e r at u r e 27

specific aspects of the pension system.24 This literature, surveyed

recently by Jefferson (2009), can generate a number of hypotheses that can be used to explain observed differences in gender balance in pensions: (1) gaps in coverage in systems linking entitlements to contribution: coverage gaps in public systems are closing as new gaps are opening up in occupational systems (p. 120), thus high-lighting the importance of following the total entitlement for all pillars, (2) benefit calculation policies— (the role of derived ben-efits such as survivors’ pension, the period of earnings taken into account, the existence of pension minima, unisex annuity tables for the second pillar),25 and (3) methods of financing and

part-shifting to funding, affecting the distribution of risk.

Most of the literature on gender and pensions is oriented toward the effects of reforms, usually focusing on a specific reform or systemic feature. In this way, the effects of combination of fac-tors, or indeed of the overall logic of systems, may be missed. This piecemeal approach begs the question of benchmarking the start-ing point: what is the current level of gender imbalance, how does it differ between countries and why?

In this respect, the United States was privileged in having access to good-quality survey data which allowed researchers to pose rel-evant questions and to ponder on causes of observed phenomena. Chief among these was the HRS, a panel survey of people 50+ which has been in operation since 1992,26 and has provided

mate-rial for a large number of studies. The SHARE was consciously modeled on the HRS. SHARE-based studies have begun appear-ing, in some cases attempting to explain income gaps in older age. Many of the papers in Börsch-Supan et al. (2011) approach the issue of broken careers (Lyberaki et al., 2013; Tinios et al., 2011).

However, when one looks at European-level data one has to get along with studies relying on local administrative data or impres-sionistic analyses of selective cases (see, e.g., Frericks et al., 2009).

A Schematic Comparison of Pay and

Pension Gaps

Gender differences begin cumulating from the world of work. The aspect most studied concerns pay per hour. Differences may be “ ‘explained” by different endowments of measurable variables (e.g., years of education), by concentration of the gender’s in different

Un equa l Age i ng i n Eu rope 28

occupation, or simply due to “discrimination.” Men and women also differ according to the hours worked per year, where there is not only different concentration in part-time work, seasonal work, or fixed-term employment but also differing propensities toward self-employment. Period earnings such as annual earnings reflect all these differences. Annual earnings cumulate through the career and are mediated by years worked. Gender differences may be due to late entry (education, military service) but are most commonly because of exit from the labor force due to childbear-ing and unemployment spells. The three aspects are multiplied to form total career resources—which could lead to a lifetime earn-ings gap (table 2.1 which elaborates on figure 2.1).

The world of retirement is predicated upon the world of work and builds on lifetime earnings. These operate through the rules of the pension system, but are also, in most cases, affected by the individual deciding on an age of retirement. The resulting pen-sion is typically affected by both features: early penpen-sions typically lead to lower pensions and the pension system may correct imbal-ances in lifetime resources, or it may amplify them (e.g., where a prefunded element may reward saving). We may distinguish three types of situations:

Some social insurance systems may lead to some individuals with

● ●

an insufficient insurance record not being entitled to a pension at all (zero pensions). In those situations, the other partner (in the case of married couples) may receive a married person’s pen-sion supplement.

Some systems may have an age pension which is received by all

● ●

citizens on reaching a particular age. In some countries, there may be a widespread use of pension-like emoluments (e.g., for having raised children in Luxembourg).

Social insurance pensions are designed to reflect lifetime

contri-● ●

butions and can be expected to mirror the career earnings gaps. Nevertheless, a number of devices (credit for childbearing peri-ods, minimum pensions) can temper this. Second pillar pensions can be expected to have a closer link to contributions, as well as to reflect possible differences in rates of return.

We must note that looking at pensions neglects benefits in kind, housing benefits, transport subsides, and eligibility of other social

29 T ab le 2 .1 In o ut lin e: T he G en de r G ap i n P en si on s a nd G en de r E ar ni ng s G ap G en de r G ap s— fr om t he P ay t o t he P en si on g ap t hr ou gh t he l ife c yc le T H E W O R L D O F W O R K A . P ay p er h ou r → P A Y GA P T O T A L C A R E E R R ES O U R C ES E du cat io n, s ki lls ( hu m an c ap it al ) Se gr eg at io n ( “w om en ’s w or k”) D is cr im ina ti on B . H ou rs W or ke d p er y ea r → H O U R S GA P → Part -t im e C on tr ac t o r s ea so na l w or k Se lf-em ploy m en t C . Y ea rs W or ke d → BR O K E N C A R E E R S L IF ET IM E E A R N IN G S G A P (= A xB xC) L at e e nt ry d ue t o e du cat io n, m ili ta ry s er vi ce U nem pl oy me nt , W or k I nt er ru pt io ns (p er io ds c re di te d f or s oc ia l i ns ur an ce a nd → ot he r c om pe ns at in g me as ur es c ou ld c or re ct ) T H E W O R L D O F R E T IR E M E N T C hoi ce of A G E O F R E T IR E M E N T P E N SI O N S Y ST E M D . P E NSI O N → P E NSI O N GA P D ep en di ng o n s ys tem — ze ro pe ns io ns . A ge p en si on s m ay b e g iv en t o a ll af te r a c er ta in a ge . O th er p en si on su pp leme nt s? So ci al i ns ur an ce p en si on s r ef le ct l ife ti me ea rn in gs g ap . M ar ri ed s up pl eme nt s. T O T A L P E N SI O N R E C E IP T S In di vi du al ly b as ed ad di ti on s (B en ef it s i n k in d? ) Se co nd -p ill ar p en si on s m ay c om po un d l ife ti me ga p. E . T O T A L PE N SI O N G A P Y E A R S I N R E T IR E M E N T / L IF E E X P E C T A N C Y Su rv iv or s’ p en si on s G en de r d if fe re nc es i n l ife e xp ec ta nc y In de xa ti on p ra ct ic es