Perceived Social Support and Psychopathology in

Patients Following a Traumatic Brain Injury

Mémoire doctoral

Melissa Amber Labow

Doctorat en psychologie

Docteure en psychologie (D. Psy.)

Résumé

Le traumatisme craniocérébral (TCC) est l’une des premières causes de décès et d’invalidité chez les adultes. À la suite d’un TCC, il est commun pour ces personnes de vivre des problèmes de santé mentale et des difficultés en lien avec le soutien social. Les objectifs de ce mémoire sont de décrire l’évolution du soutien social à travers le temps en fonction de la gravité des blessures, d’explorer les variables sociodémographiques et cliniques qui sont associées à un plus faible soutien social 24 mois après le TCC et de vérifier si le soutien social mesuré quatre mois après le TCC contribue à prédire les difficultés de santé mentale un et deux ans après un TCC. 255 adultes ayant subi un TCC léger à sévère ont été inclus dans l’étude. Les résultats de l’étude indiquent que le score de soutien social total ne change pas significativement à travers le temps ni en fonction de la gravité des blessures. Par contre, le soutien social instrumental diminue à partir de 4 mois jusqu’à 24 mois après le TCC. Les personnes avec un plus faible soutien social qui ont subi un TCC sont plus souvent sur le chômage et vivent seules. Finalement, le score de soutien social total évalué quatre mois après le TCC contribue à prédire des problèmes de santé mentale deux ans après le TCC. Ces résultats soulignent l’importance d’inclure des interventions visant le soutien social dans la période de rétablissement chez les personnes ayant subi un TCC.

Summary

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are one of the leading causes of death and disability in adults. Following a TBI, it is common for individuals to experiences various sequelae, including mental health challenges and changes in social support, amongst others. The goals of this study were to describe the evolution of perceived social support over time and across injury severity levels, to explore socio-demographic variables and clinical variables associated with lower levels of social support at 24 months post-TBI and to verify whether social support measured at four months following TBI contributed to predict the presence of mental health disorders one to two years post-injury. A sample of 255 participants with mild to severe TBIs were included in the study. The results indicate that the total social support score does not change significantly over time or according to injury severity, however instrumental social support decreased from 4 to 24 months. TBI survivors with lower social support were more often unemployed or living alone. Finally, the total social support score evaluated four months after the injury contributed to predict the presence of mental health challenges at a two-year follow-up assessment. These results indicate the importance of including social support interventions in the recovery process of TBI patients.

Table of contents

Résumé ...ii

Summary ... iii

List of tables ... vi

List of figures ... vii

Acknowledgements ...viii

Preface ... ix

Introduction ... 1

Traumatic Brain Injuries ... 1

Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Mechanism of Injury ... 1

Severity Classifications ... 2

Cognitive, Occupational, Personality, Social Cognition, and Social Relationship Repercussions following a TBI ... 3

Cognitive Impairments ... 3

Occupational Impairments... 4

Personality Changes ... 5

Impairments in Social Cognition ... 6

Impairments in Social Relationships ... 7

Summary ... 9

The Psychological Consequences of TBIs ... 9

Mood Disorders ...10

Anxiety Disorders ...11

Alcohol and Substance Use Disorders ...12

Summary ...14

Social Support...14

The Relationship Between Social Support and TBIs ...16

The Relationship Between Social Support and Psychological Well-Being in TBI Patients ...17

The Relationship Between Social Support and Socio-Demographic Variables ...18

Summary ...19 Chapter 1: Article ... 20 Résumé ...21 Abstract ...22 Introduction ...23 Methods ...27 Participants ...27 Procedure ...27 Measures ...28 Results ...30 Sample description ...30

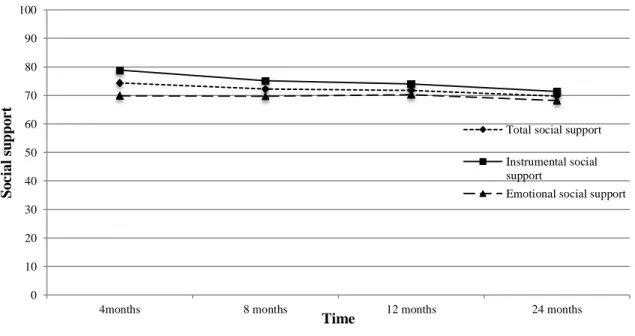

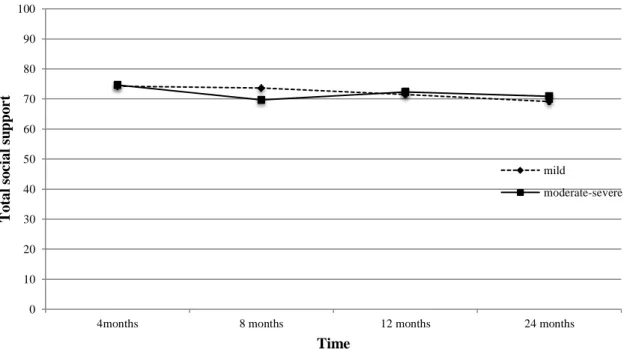

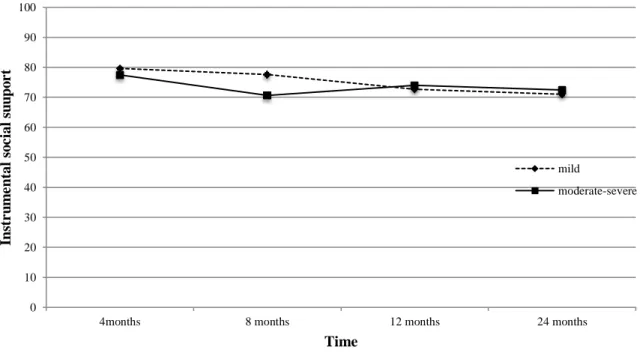

Objective 1. Social support according to time and injury severity ...31

Objective 2. Socio-demographic and clinical variables...32

Objective 3. Social support as a predictor of psychopathology ...32

Discussion ...33

References ...38

References ... 58

Appendix A... 66

Appendix B ... 71

List of tables

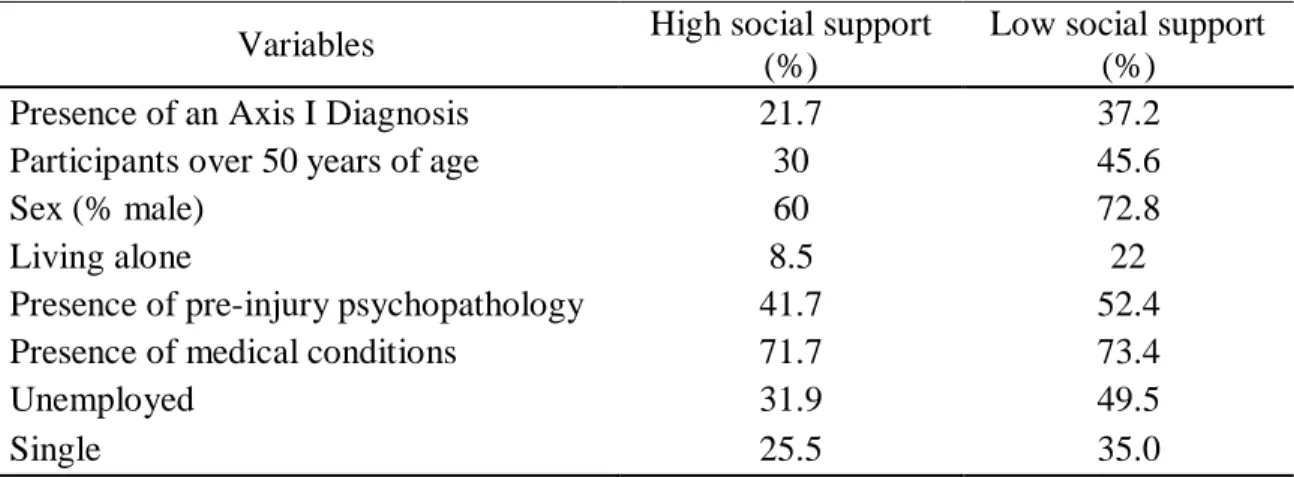

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants (N = 255)………...41 Table 2. Comparison of characteristics between the high and low social support groups....42 Table 3. Predictors of the presence of a mental health disorder two years post injury…...43

List of figures

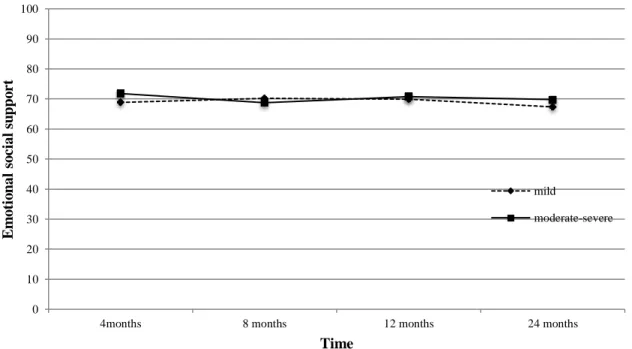

Figure 1. Flow chart of participant recruitment………44 Figure 2. mMOS-SS total at 4, 8, 12, and 24 months for the whole sample………45 Figure 3. mMOS-SS total social support score at 4, 8, 12, and 24 months according to

injury severity (mild vs. moderate/severe TBI)………46

Figure 4. mMOS-SS instrumental social support at 4, 8, 12, and 24 months according to

injury severity (mild vs. moderate/severe TBI)………47

Figure 5. mMOS-SS emotional social support score at 4, 8, 12, and 24 months according to

injury severity (mild vs. moderate/severe TBI) ………...………48

Figure 6. Number of persons in the social network at 4, 8, 12, and 24 months according to

Acknowledgements

I am forever grateful to have had the opportunity to complete my mémoire under the supervision of Dr. Marie-Christine Ouellet. She accompanied me through every step of my research project, from conceptualization to completion, and my doctoral mémoire came to fruition because of her continuous guidance and support. Dr. Ouellet’s motivation and encouragement is contagious and her passion, drive, and dedication to her research pushed me to accomplish goals that seemed otherwise daunting. Her professional and academic support has undoubtedly helped me grow not only as a student but also as a young professional. To my committee member Dr. Guillaume Foldes-Busque – I am thankful for his recommendations, thoughtful insight, and the time he has dedicated to helping me throughout this momentous journey. I would also like to recognize Dr. Simon Beaulieu-Bonneau – his passion for research and knowledge of traumatic brain injuries is inspiring and I have learnt a tremendous amount from his feedback and suggestions. I am incredibly honoured to have worked alongside all these unbelievably talented researchers and clinicians at Laval University. As well, I would like to express gratitude to the undergraduate and graduate students in Dr. Ouellet’s laboratory who contributed to data collection for my mémoire.

To my family, friends, and loved ones – my most heartfelt gratitude extends to you. I always felt your continuous love and support despite residing in different cities. Knowing I could count on all of you for constant advice and encouragement truly made my experience as a doctoral student calming. You have always been my greatest cheerleaders and these past few years would not have been the same without all of you.

Preface

I submit this doctoral mémoire to Laval University in partial fulfillment of the Doctor of Psychology in clinical psychology (D.Psy). I am the primary author of this mémoire and article and I worked alongside my supervisor, Dr. Marie-Christine Ouellet, and Dr. Simon Beaulieu-Bonneau to develop a research question, analyze statistical findings, and interpret data.

The first chapter of this mémoire is a general introduction to traumatic brain injuries and the various sequelae, such as the mental health challenges and deficits in social support, which could arise post-injury. The second chapter is an article that examined the relationship between psychopathology and social support following a traumatic brain injury, which will be submitted for publication in the fall of 2020. In the final chapter of this mémoire, findings are explored in greater detail and limitations and future recommendations are outlined.

Introduction

Traumatic Brain Injuries

A traumatic brain injury (TBI) may be the result of a direct hit or an indirect rapid acceleration, deceleration, or unrestricted movement of the head where the brain does not maintain the same momentum as the skull (Rotondi, Sinkule, Balzer, Harris, & Moldovan, 2007; Zink, 1996). The force triggers a collision between the brain and the cranium, which can cause bruising (Morris, 2010). The movement of the brain inside the cranium (from an inertial force) creates shear-strain stress, which may lead to tissue damage on the surface of the brain, in white matter, grey matter, the corpus callosum and in the brainstem, or create diffuse axonal injury (Zink, 1996). Furthermore, a TBI is classified according to whether it is a penetrating (for example if an object or fragments of the skull penetrate the brain) or a closed injury (where skull typically remains intact), the latter representing the most common form. A TBI may be the result of a primary or secondary brain injury. Primary injuries involve a physical disturbance of brain tissue as a result of a force applied to the cranium and brain at the time of impact (Zink, 1996). Secondary injuries occur post-injury and are the result of the trauma (e.g. hypoxia, swelling, ischemia, etc.). Both of these types of injuries can cause various types of sequelae. Often, a TBI is associated with symptoms such as an altered level of consciousness (confusion, disorientation), amnesia (for events immediately before or after the injury), neuropsychological and neurological abnormalities, as well as intracranial lesions (Langlois Orman, Kraus, Zaloshnja, & Miller, 2011).

Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Mechanism of Injury

Traumatic brain injuries can result in mortality and disability amongst patients. Annually in the USA, there are approximately 1.6 million individuals who sustain TBIs, 52,000 related deaths, and 80,000 individuals with lasting neurological damage (Ghajar, 2000). The NIH Consensus Development Panel noted that between 2.5 million and 6.5 million people a year in the USA are left suffering from the repercussions of their injuries (Ragnarsson et al., 1999). A trimodal distribution has typically been used when categorizing the highest incidence rates of TBI, with peaks of incidence among children aged 0 to 5 years, adolescents and young adults ranging from 15 to 24 years of age, and the

elderly population aged 75 years and older (Ragnarsson et al., 1999). In general, motor vehicle and bicycle accidents are the most common cause of TBIs, followed by falls, violence-related incidents, assaults, and sports injuries (Ragnarsson et al., 1999). The main cause of TBIs amongst children and the elderly is falls while motor vehicle accidents and violence are more common causes of TBI in adolescents and young adults (Bruns & Hauser, 2003).

TBIs are far more common amongst men compared to women during adolescence and young adulthood (Bruns & Hauser, 2003) and account for 59% of all TBI accidents in the USA (Roebuck-Spencer & Cernich, 2014). Research has also shown a positive correlation between an individual’s blood alcohol concentration and their risk of suffering from a TBI from an external cause, such as a motor vehicle accident, physical altercation, or as a result of self-injury (Taylor, Kreutzer, Demm, & Meade, 2003). A review by Taylor et al. (2003) reported that 25-75% of patients who presented to the emergency room tested positive for alcohol upon arrival. Lower socioeconomic status has also been found to be a risk factor for TBI (Roebuck-Spencer & Cernich, 2014).

Severity Classifications

In Québec, the severity of the TBI, mild, moderate or severe, is determined by physicians at the trauma center and is based on provincial guidelines (Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec & Société d'assurance automobile du Québec, 2005) which generally use the World Health Organisation definition of TBI (Carroll et al., 2004; von Holst & Cassidy, 2004). According to this definition, TBI results from an energy transfer from an external source to the skull and underlying structures, characterized by: (a) alteration or loss of consciousness (mild TBI: < 30 minutes; moderate: < 24 hours; severe: > 6 hours); (b) posttraumatic amnesia (mild: < 24 hours; moderate: generally 1-14 days; severe: several weeks); (c) any transitory neurological sign such as any focal neurological sign, convulsion, or intracranial lesion (mild: positive or negative brain imaging results, possible neurological signs; moderate: generally positive brain imaging results, presence of focal neurological signs; severe: positive brain imaging results and presence of focal

neurological signs); and (d) the initial score on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (Teasdale & Jennett, 1974) (mild: 13-15; moderate: 9-12; severe: 3-8).

The Glasgow Coma Scale, a tool used to assess one’s level of consciousness, is most commonly used to assess the severity of a head injury (Jones, 1979). If a patient has a score indicative of a mild injury (usually 13-15), they may experience brief loss of consciousness, or they may experience an alteration in their mental state (feeling disoriented, dazed, confused) or loss of memory of the events before or after the injury without losing consciousness (American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, 1993; Ghajar, 2000). When a score between 9-12 is observed and the patient loses consciousness from anywhere between a few minutes and 6 hours, this is usually indicative of a moderate injury. Last, a score indicative of a severe injury (3-8) would suggest that a patient could be unconscious for days, weeks, or even months (Morris, 2010). Studies tend to group TBI patients with moderate and severe injuries (separately from mild injuries) since they have similar care trajectories. Indeed, patients with mild injuries are often discharged more rapidly whereas more severe injuries tend to require more structured rehabilitation programs that are focused on recovery.

Cognitive, Occupational, Personality, Social Cognition, and Social Relationship Repercussions following a TBI

Individuals may experience a host of consequences after a head injury. These repercussions could vary according to the severity of the injury and often negatively impact the lives of patients. Impairments may be temporary or permanent, and rehabilitation may be lengthy before a patient returns to their pre-injury level of functioning or reach a plateau in recovery of function. Some of the most prevalent consequences of TBI are cognitive, behavioural, personality, and occupational impairments (Trevena & Cameron, 2011).

Cognitive Impairments

Cognitive impairments are one of the most common sequelae following mild, moderate, and severe TBI. Some authors suggest that these deficits generally resolve in patients with mild injuries within three months of the TBI, yet progress in sufferers of

moderate to severe injuries may only be noticed at the two-year mark (Trevena & Cameron, 2011). Difficulties with attention are nearly universal following all severity levels of a TBI (Morris, 2010) and have an impact on concentration as well as the ability to complete assigned tasks without being affected by distractions (Société de l’assurance automobile du Québec, 2002). Moreover, attention problems can hinder learning and problem solving. Speed and efficiency of cognitive processing is often affected in patients as well (Freeman, Barrett, Zappalà, & Barrett, 2011). Furthermore, there is a significant correlation between information processing speed and mental fatigue (Johansson & Rönnbäck, 2014). Lengthy cognitive tasks contribute to mental exhaustion, which impedes concentration, memory, and thinking times. Individuals may also otherwise experience temporary or permanent difficulties with long and short-term memory (Morris, 2010). Morris (2010) noted that patients with a mild TBI are more likely to experience problems with acquisition and registration of material into memory, while moderate-severe TBI patients experience deficits in consolidation and retention of material into memory. Of note, McDonald, Flashman, and Saykin (2002) suggested that shortfalls in executive functions (problem solving, planning, organizing, emotional regulation, insight, empathy, etc.) are the most incapacitating difficulties for patients within the domain of cognition. Furthermore, cognitive difficulties have been shown to be significantly related to lower mental health status (Ouellet, Sirois, & Lavoie, 2009).

Occupational Impairments

Returning to work and resuming everyday activities is challenging for a significant portion of persons with a TBI. In fact, the incapability or difficulty in returning to a remunerated employment is one of the most common long-term consequences of a TBI (Bernspang & Johansson, 2001). Returning to work following a TBI can be considered a great accomplishment and signifies the ability to reintegrate in society, it often contributes to overall self-esteem, and patients attain a greater social life (Bernspang & Johansson, 2001; Walker, Marwitz, Kreutzer, Hart, & Novack, 2006). Conversely, individuals who are unable to return to work are likely to experience a significant loss in self-esteem, considering the way in which our society highly values employment status (Lefebvre,

Cloutier, & Josée Levert, 2008). As well, unemployment places patients at greater risk for social isolation and diminished social support (Lefebvre et al., 2008).

There are several variables that are associated with return to work such as injury severity, patient’s level of education, pre-injury employment status, etc. (Walker et al., 2006). Benedictus, Spikman, and van der Naalt (2010) found that of 434 patients, 50% were able to return to work completely, while 24% were able to resume part-time work. When examining rates of return to work by injury severity, they observed that 72% of those with mild TBI were able to return to employment compared to 43% of those with moderate TBI, and 23% in those with severe TBI. These results indicate that even after a mild TBI, issues with return to work may be present. Impairments in memory and attention are thought to hinder an individual’s ability to return to work or simply limit their capacity to complete demanding tasks (Bernspang & Johansson, 2001). In general, impairments within the domain of cognition are known to increase problems in the workplace across all levels of TBI severity classifications, yet behavioural impairments are also significant in determining return to work (Benedictus et al., 2010). Dawson and Chipman (1995) found that 72% of patients reported feeling limited in the kind or amount of work and 23% were refused a job. However, patients with moderate to severe TBIs previously working in professional or managerial positions are more likely to return to work 1-year post-injury (Walker et al., 2006). Furthermore, a systematic review concluded that TBI reduced the likelihood of patients returning to work post-injury and also the likelihood of returning to the same position (Temkin, Corrigan, Dikmen, & Machamer, 2009).

Personality Changes

Behavioural changes vary according to the severity of the head injury and are more present in patients following a severe TBI (Trevena & Cameron, 2011). The following domains of personality have been described as altered following a TBI, particularly in more severely injured individuals (O’Shanick, O’Shanick, & Znotens, 2011): social perceptiveness, self-control and regulation, stimulus-bound behaviour, emotional change, and the failure to learn from social experience. These traits can impact social relationships and may result in alienation from others (O’Shanick et al., 2011). Furthermore, childish

behaviour has also been seen in patients following a TBI. Difficulty with skills that are typically acquired during development, like turn taking and sharing, re-emerge (O’Shanick et al., 2011) and behavioural changes such as impulsivity, disinhibition, and hyperverbosity tend to emerge (Cicerone & Maestas, 2014). Individuals may also behave aggressively (physically or verbally), become irritable or may be unpredictable (O’Shanick & O’Shanick, 2005). The most common behavioural problems in a sample of 65 patients with severe TBI were irritability (49%), being argumentative (44%), and anger (42%) at 6 months post-injury (Kersel, Marsh, Havill, & Sleigh, 2001). Personality traits that were present prior to the injury may also be intensified after the accident, although more research is required in order to examine this question more definitively (O’Shanick & O’Shanick, 2005)

These changes can represent considerable difficulties for family members and caregivers (Fleminger, 2008) and can cause friction in relationships especially if patients become more irritable, impatient, aggressive, experience frequent mood fluctuations, or have difficulty regulating their emotional state (Société de l’assurance automobile du Québec, 2002).

Impairments in Social Cognition

There are many underlying neuroanatomical structures and systems that regulate social cognition which may be affected by the injury, and therefore influence the ability to understand others, communicate effectively, guide social behaviours, etc. (McDonald, 2013). It has been shown that 70% of patients with a severe TBI had significant difficulty empathizing with others post-injury (de Sousa et al., 2010). In children and adolescents with moderate and severe TBIs, issues with social cognition have also been associated with injury severity (McDonald et al. (2013).

Nonverbal communication conveys information through facial expressions, gestures, and vocal intonation, for instance, which play a meaningful role in social interactions (Spell & Frank, 2000). It was noted that 39% of severe TBI patients had difficulties identifying emotions from static facial expressions (McDonald, 2013) and greater impairments on this task were associated with TBI severity (Spikman, Timmerman,

Milders, Veenstra, & van der Naalt, 2012). Patients also experienced problems recognizing emotional expressions when listening to another adult compared to control subjects (McDonald & Flanagan, 2004; Spell & Frank, 2000). These authors suggest that additional interventions may be necessary in order to work towards improvements in nonverbal communication, which could favour social and work reintegration. Patients may also lack judgement or social awareness, and therefore have difficulty analyzing situations, which for example may manifest in their inability to detect sarcastic remarks (O’Shanick et al., 2011). The literature has shown, however, that patients did not have difficulties interpreting literal comments, such as lies and sincere statements (McDonald & Flanagan, 2004).

Impairments in Social Relationships

A TBI could have a negative impact on work relationships, friendships, couples, and family members. In fact, patients with moderate and severe TBIs often experience a decrease in number of friendships (Dijkers, 2004). Social networks (the number, frequency, and intimacy involved in social interactions) are essential post-TBI because they can help with the coping and recovery process as well as complement the domains of functioning that were impacted by the trauma (Kozloff, 1987). However, they may be affected by the nature of the injury as well as the behavioural changes that accompany it. Social contact has been shown to decrease 6 months post-injury and deteriorate even further 1 year after the injury (Kersel et al., 2001). Findings from Kozloff (1987) suggested that patients with severe TBIs noticed a decrease in their social relationships and a feeling of isolation from peers. Patients with severe TBIs received fewer visits from family and friends, reduced their visits to family members, and were less likely to report good family relationships over time (Kersel et al., 2001). A survey with 454 TBI participants found that 45% never talked on the phone, 27% never socialized with friends or family, 19% never visited friends or relatives and that around 90% reported some kind of social limitation (Dawson & Chipman, 1995). Dikmen, Machamer, and Temkin (1993) revealed significant impairments in social interactions in patients with moderate and severe TBIs at 1, 12, and 24 months post-injury. Thomsen (1984) evaluated severe TBI patients between 2.5 and 10-15 years post-injury and revealed 60% of them lost social contacts at 2.5 years post-injury and 68% at 10-15 years of follow-up. A long-term study by Hoofien, Gilboa, Vakil, and Donovick (2001) revealed

that between 10-20 years following a severe TBI, 31.1% of patients had no social contacts aside from family members and 8.2% of participants were completely isolated. Across a 5-year period of analysis, social relationships remained impaired, with 90% of patients reporting difficulties related to social contact at each time period (6, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months post-TBI) (Lezak, 1987). Social isolation appears to be a chronic problem in severe TBI patients and socialization issues may even worsen with time (Gordon et al., 2015). As well, participants with moderate and severe TBIs had been found to have significantly lower social functioning scores (which include family relations and friendships) compared to mild TBI participants (Scholten et al., 2015).

Memory and concentration issues could hinder verbal exchanges between friends and family and limit the continuation or forming of relationships (Lefebvre et al., 2008). Furthermore, weakened communication skills, poor self-control, mobility limitations, and decreased interpersonal skills could make it more difficult for patients to form new friendships (Dijkers, 2004). Several personality and behavioural factors that could contribute to social isolation are sexual disinhibition, inappropriate laughing, and verbal and physical abusiveness (Kozloff, 1987). These changes, of which the patient is not always cognizant, affect interpersonal relationships and cause distress among family members (Cavallo & Kay, 2005). Relationships with family members may also become more intense, stressful, and conflictual (Dijkers, 2004). Family members further reported feeling a high sense of burden (Hoofien et al., 2001), which increased over time (Cavallo & Kay, 2005). Studies have also shown that TBIs could have an impact on marital relationships, romantic partners, and couples and as many as half of patients were separated after their TBI (Kersel et al., 2001; Lefebvre et al., 2008). The attitude of the spouse towards the changes in their companion might contribute to conflicts in the relationship (Lefebvre et al., 2008). Authors were unable to confirm whether or not severity of injury contributed significantly to divorce and separation in TBI patients (Wood & Yurdakul, 1997).

Moreover, the entire family system may be affected even if only one member suffered from a TBI (Cavallo & Kay, 2005). Caregivers report experiencing significantly high levels of emotional distress, anxiety, as well as psychotic, obsessive-compulsive, and

hostile symptoms while caring for a TBI patient (Gervasio & Kreutzer, 1997; Kreutzer, Gervasio, & Camplair, 1994). Unhealthy family functioning, influenced by the behavioural and cognitive difficulties of the patient, intensified psychological distress in spouses/caregivers (Anderson, Parmenter, & Mok, 2002).

Summary

Following a TBI, depending on the severity of the injury, patients may experience multiple cognitive, behavioural, occupational, and social repercussions (in the domain of social cognition and social relationships), all of which could have a negative impact on the patient. Furthermore, these domains overlap, and sequelae in one domain may trigger setbacks in another (e.g. cognitive difficulties may directly impact a patient’s ability to return to work). It is understandable that the impact of these issues could contribute to psychopathology in patients following a TBI. Interactions between social and psychological consequences of TBI are of great importance and will be explored in more detail for the purpose of this research project.

The Psychological Consequences of TBIs

The literature has demonstrated that mental health challenges are prominent in a TBI population and psychiatric disorders are generally more prevalent compared to the general population (Schwarzbold et al., 2008). A systematic review by Scholten et al. (2016) revealed that the incidence of rates of an Axis I disorder post-TBI varied between 5% and 47%, regardless of injury severity. In a sample of patients with moderate to severe TBI, one study identified psychiatric diagnoses to be as high as 61.8% within the first year post-injury (Alway, Gould, Johnston, McKenzie, & Ponsford, 2016). TBI severity is generally not related to the severity of psychological symptoms (Horner, Selassie, Lineberry, Ferguson, & Labbate, 2008). Furthermore, psychiatric sequelae can have an impact on rehabilitation and patient’s abilities to return to an autonomous level of functioning (Kim et al., 2007). Detailed analysis of mood, anxiety, and substance disorder is of considerable importance considering these are the most frequently diagnosed mental health problems post-injury (Gould, Ponsford, Johnston, & Schonberger, 2011).

Mood Disorders

Depression is the most common mental health problem in individuals following a TBI (Moldover, Goldberg, & Prout, 2004). The prevalence rates of depression after a TBI have been shown to be between 18.5% and 61% (Kim et al., 2007), with the variability partially explained by patient characteristics, time since injury, diagnostic criteria, and how depression was conceptualized and measured (Osborn, Mathias, & Fairweather-Schmidt, 2016). The findings of a meta-analysis by Osborn et al. (2014) indicated that among 93 eligible studies, conducted between January 1980 and June 2013, 27% of patients with a mild-severe TBI received an official diagnosis of major depressive disorder or dysthymia while 38% of individuals indicated clinically significant symptoms on self-report questionnaires. Trevana and Cameron (2011) indicated that spontaneous recovery from depression without treatment occurs in more than half of TBI patients. However, other data suggest that depressive symptomatology appears to remain stable over time in patients following a TBI (18% at 3 months post-TBI, 13% at 1 year post-TBI, and 18% at 5 years post-TBI) (Sigurdardottir, Andelic, Roe, & Schanke, 2013) across all classifications of severity (mild, moderate, severe). The most prominent symptoms of depression reported amongst TBI patients were feelings of hopelessness, worthlessness, and diminished pleasure in activities (Trevena & Cameron, 2011). However, according to some authors it is important to nuance these findings, because diagnoses of depression could be over or under represented in TBI patients. For example, symptoms like sleep difficulties and fatigue might be considered as part of the depressive syndrome yet may also be a separate consequence of a TBI, which would result in over-diagnosing of depression (Horner et al., 2008). However, other authors found that including somatic symptoms does not result in overestimating major depressive disorder diagnoses in persons with a TBI (Cook et al., 2011; Seel, Macciocchi, & Kreutzer, 2010). In addition, within the first six months of the accident, a patient’s insight or awareness into their difficulties may be limited, which would cause them to underestimate their symptoms (Moldover et al., 2004).

Moldover et al. (2004) suggested two possible pathways to explain the onset of depression: first, depressive symptoms may be the result of neural damage or, second, may be in reaction to the accident or repercussions experienced thereafter (e.g., cognitive).

Depression may also result from a combination of both pathways. Other variables that were found to be strongly predictive of depression were anxiety, psychosocial stressors, increasing age, and change in employment status (employed pre-injury and unemployed post-injury) (Sigurdardottir et al., 2013).

TBI patients with depressive symptoms have been shown to have increased difficulties with close personal relationships at baseline, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months of follow-up (Gomez-Hernandez, Max, Kosier, Paradiso, & Robinson, 1997). These authors also confirmed that depressed individuals experienced greater fear surrounding job security compared to their control counterparts. Depression was also related to cognitive deficits in the domains of attention, memory, and executive functioning at 6 months of follow-up in mild and moderate TBI patients (Rapoport, McCullagh, Shammi, & Feinstein, 2005). Furthermore, depression was also significantly correlated with lower quality of life as well as lower satisfaction with life (Goverover & Chiaravalloti, 2014).

Anxiety Disorders

Although the findings in the literature remain mixed, a review by Mallya, Sutherland, Pongracic, Mainland, and Ornstein (2015) revealed that generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) was the most common anxiety disorder diagnosis post-TBI. The prevalence rates of GAD post-injury were varied with percentages ranging from 2.5% to 24% (Hiott & Labbate, 2002). Prevalence rates higher than in the general population have also been noted post-injury for other anxiety disorder diagnoses such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 13% to 24%), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; 2% to 15%), and phobic disorders (1% to 10%) (Mallya et al., 2015). A meta-analysis by Osborn, Mathias, and Fairweather-Schmidt (2016) reported that persons with a TBI were three times more likely to self-report severe anxiety symptoms compared to healthy controls. However, the prevalence rates of GAD diagnoses from clinical interviews were lower then those from anxiety self-report scales at 10%, while clinically significant self-report anxiety was 37% (Osborn et al., 2016). Both diagnoses and symptoms peaked 2 to 5 years following a TBI. The severity of the injury played a significant role in the presence of symptoms. In mild

TBI, 10% had a GAD diagnosis while 53% presented significant symptoms on self-report scales (Osborn et al., 2016). In severe TBI, GAD diagnoses were more frequent at 15% but 38% had significant symptoms on the self-report scales. It is thus important to consider the respective limitations of structured questionnaires (for example, patients might report expected TBI symptoms, which would result in overrepresentation of problems) and clinical interviews (for example, patients may under report symptoms out of fear of embarrassment) (Iverson, Brooks, Ashton, & Lange, 2010).

One study indicated that patients with a history of an anxiety disorder were at 9.47 times the risk of having an anxiety disorder post-injury than those without a pre-existing anxiety disorder (Gould et al., 2011). The same team observed that new anxiety disorders emerged in 40% of participants within the first 6 months following a TBI. A systematic review by Scholten et al. (2016) indicated that risk factors related to anxiety included older age, female sex, pre-injury unemployment, pre-injury anxiety disorders, and all TBI severity levels. Furthermore, other risk factors such as symptoms of distractibility, fatigue, and perplexity were significantly correlated to symptoms of anxiety and pathological worry (Lezak, 1987; Moore, Terryberry-Spohr, & Hope, 2006). More specifically, PTSD symptoms might develop in patients with a mild TBI if they consider having experienced a traumatic event once regaining consciousness (Bryant, 2001).

Some of the most prevalent manifestations of anxiety post-TBI include fearfulness, intense worry, social withdrawal, generalized uneasiness, and anxious dreams (Rao & Lyketsos, 2002). The emergence of an anxiety disorder diagnosed following a TBI can have serious consequences on length of recovery and are strong predictors of social, personal, and work deficits (Mallya et al., 2015). For example, those who suffer from PTSD after a severe TBI have been shown to have more aggression, decreased quality of life, and lower productivity (Bryant, Marosszeky, Crooks, Baguley, & Gurka, 2001).

Alcohol and Substance Use Disorders

Alcohol and substance use is known as one of the most common risk factors of TBIs. A review by Taylor et al., (2003) found that 44% to 79% of patients with a TBI had a history of alcohol abuse and 21% to 37% had a history of substance use, in which

marijuana was noted as the most frequently consumed illicit drug. Furthermore, Parry-Jones, Vaughan, and Miles Cox (2006) noted that alcohol abuse 1 to 5 years post-injury varied from 7% to 26% and post-TBI substance abuse ranged from 2% to 20% in patients. In fact, substance abuse patterns were shown to shift within the first year post-injury, such that they declined at month 4 and then increased towards month 8 (Beaulieu-Bonneau et al., 2018). Patients with a history of alcohol or drug abuse are at risk of post-injury substance misuse (Bjork & Grant, 2009; Parry-Jones et al., 2006). A history of substance abuse was linked to higher mortality, severity of injury, likelihood of complications, poorer neurological outcome, and increased likelihood of suffering from several TBIs (Corrigan, 1995). As well, it is impossible to establish a causal relationship between a TBI and the risk of developing a new substance abuse problem because of the limited existing literature (Bjork & Grant, 2009).

Some of the risk factors associated with post-TBI substance abuse consisted of the following: pre-injury history of alcohol or drug abuse, intoxication at the time of the TBI, history of legal problems related to abuse, family and/or friends with substance abuse, and denial of dangers associated with abuse (Taylor et al., 2003). The severity of the injury did not differ in TBI patients with and without alcohol abuse/dependence (Jorge et al., 2005).

Patients with alcohol abuse/dependence were found to have worse premorbid social support and decreased functioning in the social and vocational domains compared to those without abuse (Jorge et al., 2005). Patients have also reported that social isolation was linked to addiction, which resulted in cognitive impairments and hindered social relationships (Lefebvre et al., 2008).

Substance abuse post-injury was shown to have a negative impact on the course of rehabilitation (Corrigan, 1995), which accentuates the importance of early recognition of risk factors, the development of treatment plans (Taylor et al., 2003), as well as the reinforcing of prevention strategies (Beaulieu-Bonneau et al., 2018). Jorge et al. (2005) found that of the 20 patients with alcohol abuse post-injury, 75% developed a mood disorder and these patients showed worse vocational functioning, which may possibly be amplified by the neurological deficits as a result of the injury. As well, patients with

alcohol abuse/dependence who returned to work were proportionally less in comparison to patients without (Jorge et al., 2005). Other outcomes associated with substance abuse post-injury were lower employment and independent living status, decreased satisfaction with life, and increased rate of suicide (Parry-Jones et al., 2006).

Summary

Following a TBI of varying severities, anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders can have negative consequences and impact social, occupational, behavioural, and cognitive domains of functioning. These repercussions can alter rehabilitation and overall well-being in patients post-TBI. As well, the likelihood of suffering from multiple simultaneous diagnoses is increased given the often comorbid nature of mental health problems. The interaction between these psychopathologies and the social sphere, more specifically the domain of social support, will be further explored in the interest of this research project.

Social Support

Social support was defined by Hupcey (1998) as, “a well-intentioned action that is given willingly to a person with whom there is a personal relationship and that produces an immediate or delayed positive response in the recipient” (p. 313). Nevertheless, authors have suggested that this term might not be clearly defined, which would have an impact on the way that it is measured and studied (Finfgeld‐Connett, 2005; House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988; Hupcey, 1998). The precursors of social support consist of the need for social support (Hupcey, 1998), an intact social network, and a social climate (Finfgeld-Connett, 2005). Individuals must acknowledge their need, accept support, and may offer support to others. Friends and family members are often considered part of a person’s social network and have essential qualities like being available, trustworthy, and reliable (Finfgeld-Connett, 2005). In addition, reciprocity is of utmost importance for both the individual giving and receiving social support (Finfgeld-Connett, 2005).

The literature differentiates perceived and received social support. Perceived social support is related to an individual’s perception that support is accessible to them (Helgeson,

1993). Received social support is quantified by tangible acts of supportive behaviour that are provided by a social network (for example, receiving help for chores, receiving flowers or receiving a card) (Helgeson, 1993). Furthermore, the concept of providing as well as receiving social support might generate the greatest amount of psychological benefits (Shakespeare-Finch & Obst, 2011).

Although the literature identifies various types of social support (e.g. emotional, informational, tangible, esteem, affectionate support), there are two primary dimensions of functional social support (or perceived social support): emotional and instrumental support. Emotional support can include comforting gestures offered to another person with the intention of diminishing feelings of anxiety, stress, hopelessness, and depression (Finfgeld-Connett, 2005). Emotional support can be offered by listening, expressing esteem (Semmer et al., 2008), communicating by telephone or by internet, conversing with one another, sending flowers, offering encouragement, etc. (Finfgeld-Connett, 2005). Instrumental support consists of offering tangible goods or help to another person (House et al., 1988). For example, offering tangible support like food, furniture, transportation, physical care, shelter, money, or helping with a task are considered instrumental support (Semmer et al., 2008). Instrumental and emotional social support might also vary within different relationships (for example, professional relationships may be predominantly instrumental in nature while emotional support plays a more meaningful role in personal relationships) (Semmer et al., 2008). The structural component of social support refers to the number of people that one would consider having in their social network (Semmer et al., 2008), whether it be contacts with friends, family, or in the community (Cohen & Syme, 1985). In fact, the functional component of social support would be expected to be a better predictor of health (Cohen & Syme, 1985; Wills & Shinar, 2000) and was found to be of greater importance compared to the number of people within the patient’s social network (Tomberg, Toomela, Ennok, & Tikk, 2007).

Social support is important during challenging and stressful moments and is meant to offer a person affirmation, validation, encouragement, reassurance, and reinforcement (Finfgeld-Connett, 2005). The literature attempts to explain the correlation that exists between social support and psychological and physical health by using two models. The

stress-buffering model suggests that social support could act as a buffer between a stressful event and the stress reaction by limiting the maladaptive emotional, physiological, and behavioural responses that could lead to illness (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Social support is also thought to help individuals decrease the perceived importance of the stressful event and therefore diminish the emotional stress reaction associated with it (Cohen & Wills, 1985). The main effects model, however, suggests that social relationships and support are related to well-being regardless of whether or not a stressful event is present (House et al., 1988).

The Relationship Between Social Support and TBIs

A literature review revealed that several studies have found a significant decrease in social support between six months and two years following a TBI and that the injury increased the possibility of experiencing reduced social support (Morton & Wehman, 1995). The results of a study by Izaute et al. (2008) illustrated that students having sustained a mild to severe TBI reported lower levels of perceived available social support (the number of people noted as offering support), compared to neurologically intact students. Moreover, a separate study provided evidence that patients with a moderate or severe TBI, compared to a healthy control group, stated significantly lower levels of satisfaction with social support as well as perceived supporters (Tomberg, Toomela, Pulver, & Tikk, 2005). These authors found that family members were the main source of social support in the control and patient group and lower satisfaction scores in patients might have resulted from needs that were not met satisfactorily. Further, social support decreased significantly between the time of hospitalization (baseline) and one year following a traumatic injury (Agtarap et al., 2017) and satisfaction with social support was diminished at between, on average, 2.3 and 5.7 years post-TBI (Tomberg et al., 2007). In patients with moderate-severe TBIs one year or longer post-injury, lower levels of perceived social support were significantly correlated to increased loneliness (McLean, Jarus, Hubley, & Jongbloed, 2014). As well, several authors noted that TBI severity was not correlated to social support (Pugh et al., 2017; Tomberg et al., 2007).

Following a TBI, it has been suggested that the change and decrease that patients experienced with regards to their social relationships increases their dependence on family members (Kozloff, 1987; Morton & Wehman, 1995). However, changes in the nature and frequency of relationships and the amount of support decreases following the early stages of recovery (Gordon et al., 2015). Ergh, Rapport, Coleman, and Hanks (2002) noted that a family’s willingness to continue caring for their loved one post-TBI diminished over time. Once the injured person’s life was no longer in danger, their social network limited their visits. As well, family and friends demonstrated less sympathy towards the needs of TBI patients (Kozloff, 1987). Spouses frequently perceived less social support after their partner suffered a TBI (Cavallo & Kay, 2005).

The Relationship Between Social Support and Psychological Well-Being in TBI Patients

Previous research confirms that social support is a protective factor against a number of physical and psychological health problems. Having several social support resources could act as a buffer when a person is faced with difficult situations and is more vulnerable (Ostberg & Lennartsson, 2007). In fact, there is a link between having fewer social support resources and increased morbidity (House et al., 1988) and negative mood (Gordon et al., 2015). Ouellet et al. (2009) found that a lower social support score was significantly associated with a lower mental health status in TBI patients. In a study that assessed moderate and severe TBI patients between 5 and 6 years post-injury, emotional well-being and general health were associated to the quantity of social supporters and their satisfaction with social support (Tomberg et al., 2007). Furthermore, one study suggested that there was a greater possibility of developing mood or anxiety symptoms after the injury if the patient presented with inadequate social support (Horner et al., 2008), and psychological symptoms could increase isolation (Lefebvre et al., 2008). Douglas and Spellacy (2000) revealed that social support accounted for 40% of the variance in depression in their sample of 35 severe TBI participants. Some authors highlight that improving social interactions through the implementation of early intervention programs could diminish depressive symptoms in mild to severe TBI patients with diminished social support (Gomez-Hernandez et al., 1997).

On the contrary, in a sample of 39 patients with mild to severe TBI, Leach, Frank, Bouman, and Farmer (1994) reported that perceived social support from family members was not significantly predictive of depressive symptoms. Another team also did not find that baseline social support was linked to depressive symptomatology in patients having sustained a traumatic injury 12 months post-injury (Agtarap et al., 2017). In a sample of TBI patients with alcohol abuse pre-injury, Jorge et al. (2005) concluded that there was no difference in the presence of social support networks in patients who relapsed post-injury compared to those who did not.

A bidirectional hypothesis might suggest that having a history of psychopathology could contribute to less optimal future social relationships. Poor social support may be the result of the inherent symptoms that manifest within a pre-existing disorder (Monroe & Steiner, 1986). In the literature pertaining to depression in general, it has been suggested that depressed individuals might foster relationships with less accessible social support reflecting the way they interact with people in their surroundings (Leach et al., 1994). For example, depressive symptomatology might drive away social support because of the persistent negative emotions expressed by patients (Taylor, 2011). In fact, one study indicated that patients with depressive symptoms at baseline had reduced social support at 12 months post traumatic injury (Agtarap et al., 2017). It is possible that social support may be refused by a person enduring extreme stress or if they feel that the support is not openly available to them (Taylor, 2011).

The Relationship Between Social Support and Socio-Demographic Variables Social support could vary across a series of variables such as age, sex, employment status, pre-injury psychiatric history, living arrangement, physical health problems, and relationship status. In a TBI sample, one study by Tomberg et al. (2005) reported that women revealed significantly higher levels of social support compared to men. These same authors noted that younger patients (less than 50 years of age) had a more vast social network compared to their older counterparts (Tomberg et al., 2005). With regards to employment, a positive and satistically significant correlation between work adjustment, the amount of supporters, and the satisfaction with social support was found (Tomberg et

al., 2007). Last, having some physical health problems such as HIV, cancer or epilepsy, might carry stigma, and this could distance the caregiver from the patient (Taylor, 2011).

Summary

Overall, the current literature highlights that social support appears to decrease in patients following a TBI. This decline might result from a fatigue in the social network, bearing in mind that the nature and consequences of the injury may be challenging or a burden for carers. As well, pre-existing mental health problems might contribute to a more limited social support network, however the literature appears mixed with respect to how social support impacts psychopathology post-injury. The results diverge with some authors noting the importance of social support in decreasing psychopathology, while others did not find any significant relationship between these constructs. Thus, it would be useful to examine the relationship between social support and Axis I disorders (e.g. mood and anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder) post-TBI, as assessed with gold standard measures such as structured clinical interviews. At two years post-TBI, the critical period of recuperation has passed and the majority of people should be back in the community and reintegrated into social roles. However, psychosocial and emotional sequelae may impede this milestone and therefore, documenting patient’s perceived level of social support across this time frame is important.

The instruments used to measure social support also vary considerably between previous studies, which complexifies the interpretation of the existing literature. As well, existing research appears limited in light of how TBI severity may alter social support in patients. Therefore, this study sets out to investigate social support longitudinally in a sample encompassing all levels of injury severity (mild, moderate, and severe).

Chapter 1: Article

The Relationship Between Perceived Social Support and Psychopathology in Patients Following a Mild to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury

Amber Labowa,b, M.Sc., Simon Beaulieu-Bonneau, Ph.D.a,b & Marie-Christine Ouelleta,b,c,

Ph.D.

a School of Psychology, Laval University, Quebec, Quebec, Canada

b Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Rehabilitation and Social Integration, Quebec,

Quebec, Canada

c CHU de Quebec Research Center, Quebec, Quebec, Canada

Corresponding author: Marie-Christine Ouellet PhD

Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Rehabilitation and Social Integration Institut de réadaptation en déficience physique de Québec

525 boulevard Hamel, Quebec, Quebec, Canada, G1M 2S8 Phone: 1-418-529-9141 #6726

Fax: 1-418-529-354

Résumé

Le traumatisme crânien (TCC) peut entraîner de nombreuses conséquences, incluant des changements du soutien social et de la santé mentale. Les objectifs de l’étude étaient de décrire l’évolution du soutien social en fonction du temps et de la sévérité du TCC, d’explorer les variables sociodémographiques et cliniques associées à un faible niveau de soutien social, ainsi que de vérifier si le soutien social mesuré quatre mois suivant un TCC contribue à prédire l’apparition d’un trouble de santé mentale un à deux après un TCC. Les résultats indiquent que le soutien social ne change pas à travers le temps ni en fonction de la sévérité du TCC, mais le score quatre mois après le TCC contribue à prédire la présence d’un trouble de santé mentale un à deux ans après le TCC. Il est primordial d’inclure des interventions portant sur le soutien social dans le processus de rétablissement après un TCC.

Abstract

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are one of the leading causes of death and disability in adults. Various sequelae, including mental health challenges and changes in social support, commonly present subsequent to a TBI. The objectives of this study were to describe the evolution of perceived social support over time and across injury severity levels, to explore socio-demographic and clinical variables associated with lower levels of social support at 24 months post-TBI and to verify whether social support measured at four months post-TBI contributed to predict the presence of mental health disorders one to two years after the injury. The results indicated that total social support did not vary significantly over time, though instrumental social support was observed to have decreased from 4 to 24 months. TBI survivors with lower social support were more often unemployed or living alone. Total social support evaluated four months after the injury contributed to predict the presence of mental health challenges two years post-injury. These results suggest that including social support interventions in the recovery process in TBI patients is essential.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injuries are a leading cause of morbidity, mortality, and disability. Annually in the USA, there are approximately 2.8 million individuals who sustain TBIs, 2.5 million emergency room visits, 50,000 related deaths, and 282,000 hospitalizations (Taylor, Bell, Breiding, & Xu, 2017). It is common for individuals to experience various consequences following a head injury. Cognitive, behavioural, personality, and occupational impairments are some of the most common sequelae of a TBI (Trevena & Cameron, 2011), particularly in patients with more severe injuries (McDonald, 2013; Trevena & Cameron, 2011). Furthermore, patients may experience significant strain on social relationships and social support, as well as being at increased risk for mental health issues.

Patients with moderate and severe TBIs often experience a decline in friendships (Dijkers, 2004), interpersonal relationships (Douglas, 2019) and social support (Pugh et al., 2017). Social support has been shown to decrease significantly between the time of hospitalization and 12 months post-TBI (Agtarap et al., 2017). A literature review revealed that findings of several studies also suggest that social support decreases significantly between six months and two years post-injury (Morton & Wehman, 1995). The results of a study by Izaute et al. (2008) found that, compared to neurologically intact students, students having sustained a mild to severe TBI with both high and low levels of social re-integration, which was determined according to their return to work, experienced significantly lower levels of perceived available social support. Moreover, a separate study indicated that patients with a moderate or severe TBI reported significantly lower levels of satisfaction with social support as well as less perceived supporters compared to a healthy control group (Tomberg, Toomela, Pulver, & Tikk, 2005). Ergh, Rapport, Coleman, and Hanks (2002) found that within families, readiness to continue caring for an injured person diminished over time. As perceived by the patient’s, once the patient’s life was out of danger, visitation from those in their social network lessened and family and friends became less sympathetic towards the needs of TBI patients (Kozloff, 1987). Likewise, spouses perceived a loss of support after their partner suffered a TBI (Cavallo & Kay,

2005). Diminished social support as reported in the TBI population, plays an important role in mental health.

TBI is known for having an impact on the mental health of patients and the incidence rates of psychiatric disorders are higher than in the general population (Schwarzbold et al., 2008). A systematic review found that prevalence rates varied between 5% and 47% with respect to the development of an Axis I disorder post-injury, according to the DSM-V, regardless of injury severity (Scholten et al., 2016). One study found that psychiatric diagnoses were greatest within the first year post-injury and prevalence was as high as 61.8% in patients with moderate to severe TBIs (Alway, Gould, Johnston, McKenzie, & Ponsford, 2016).

In general, having numerous social support resources decreases an individual’s vulnerability when faced with difficult or stressful situations (Ostberg & Lennartsson, 2007). Social support is known to act as a buffer between a stressful event and the stress reaction by limiting the maladaptive emotional, physiological, and behavioural responses that could lead to illness (Cohen & Wills, 1985). In fact, having fewer social support resources has been linked to increased morbidity (House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988) and could have a negative impact on mood (Gordon et al., 2015). Particular to a TBI sample, Ouellet, Sirois, and Lavoie (2009) revealed that a lower social support score was significantly associated with a lower mental health status. In another study assessing patients with moderate and severe TBI on average 2.3 and 5.7 years post-accident, the number of social supporters and satisfaction with social support was significantly and positively correlated with emotional well-being and general health (Tomberg, Toomela, Ennok, & Tikk, 2007). One study suggests that inadequate social support increased the possibility of developing mood or anxiety symptoms post-TBI (Horner, Selassie, Lineberry, Ferguson, & Labbate, 2008). Douglas and Spellacy (2000) studied 35 severe TBI patients and found that social support accounted for 40% of the variance in depression. The literature is somewhat mixed however, with Leach et al. (1994) observing that perceived social support from family members was not significantly predictive of depressive symptoms in a sample of 39 mild, moderate, and severe TBI patients. Nonetheless, some authors suggest that early interventions targeting social interactions could diminish

depressive symptoms in mild to severe TBI patients with diminished social support (Gomez-Hernandez, Max, Kosier, Paradiso, & Robinson, 1997).

A bidirectional hypothesis might suggest that history of psychopathology could sometimes negatively affect future social relationships. For example, the presence of psychological symptoms after TBI has been linked to increased isolation (Lefebvre, Cloutier, & Josée Levert, 2008). Patients with depressive symptoms at baseline had reduced social support at 12 months post-TBI (Agtarap et al., 2017), which might result from the way depressed patients interact with people in their environment (Leach, Frank, Bouman, & Farmer, 1994). There may even be times when social support is turned away if a person is enduring extreme stress or if the support is not be made readily available to them in the first place (Taylor, 2011).

Social support could also be linked to a variety of sociodemographic factors such as age, sex, employment status, pre-injury psychiatric history, living arrangements, physical health problems, and relationship status. For example, femininity has been associated with emotional support, while masculinity seems more associated with tangible support (Reevy & Maslach, 2001). Only Tomberg et al. (2005, 2007) seem to have examined the link between social support and sociodemographic factors specifically in the context of TBI. In one study, women with TBI reported significantly higher levels of social support compared to men, and TBI patients who were younger than 50 years of age had a greater number of people in their social network compared to patients older than 50. With regards to employment, a significant correlation was reported between work adjustment, the number of supporters, and the satisfaction with social support. They noted, however, that the number of supports in the social network were not significantly correlated with various health parameters (e.g., bodily pain, energy).

Taken together, findings from the literature indicate that social support appears to decrease in patients following a TBI (Morton & Wehman, 1995). Changes in this domain might result from a fatigue in the social network, considering the nature and consequences of the injury may be demanding or a burden for carers (Perlesz, Kinsella, & Crowe, 2000). Pre-existing psychopathology could also be considered as a possible contributor to a more

limited social support network (Leach et el., 1994). The literature diverges with some authors noting the importance of social support in decreasing symptoms of depression or anxiety after TBI, while others do not observe a significant relationship between these variables. Another limitation is that the instruments used to measure social support vary tremendously in previous studies, as each questionnaire measures a different subscale of social support. As well, research appears limited in light of how TBI severity may impact social support. Therefore, it is useful to examine social support longitudinally in a sample encompassing all levels of injury severity.

Given the importance of social support for health and the changes that might result in the network following a TBI, it is crucial to have a better understanding of how social support evolves following a brain injury, of which factors may be linked to lower social support, and to evaluate how social support may influence mental health after TBI. The present study aims to create a better understanding of the longitudinal link between psychopathology and social support following a TBI. At two years post-TBI, the critical period of recuperation has finished and the majority of people should be back in the community and reintegrated into social roles. However, psychosocial and emotional sequelae may impede this milestone and therefore, documenting patient’s perceived level of social support across this time frame is important. The specific goals of this research project were thus to: (1) describe the evolution of perceived social support over time (4, 8, 12, 24 months post-TBI) and across injury severity levels (mild and moderate/severe), (2) to explore socio-demographic variables (age, sex, presence of psychopathology pre-injury, relationship status, living arrangements, physical health problems, employment status) and clinical variables (presence of post-injury psychopathology) associated with lower levels of social support at 24 months post-TBI and (3) to verify whether social support measured early after the injury, i.e. at 4 months post-TBI, contributes to predict the presence of mental health disorders in the longer term, one to two years post-injury, while controlling for pre-injury psychopathology and socio-demographic variables. We expected that perceived social support would diminish within the first two years post-injury, reflecting a potential fatigue in the social network. We expected this decline to be more evident for participants with moderate/severe injuries compared to those with mild injuries because of the more noticeable behaviour and personality changes associated with more severe

injuries, as well as possibly more marked deficits in social cognition. We expected participants with lower social support to include more individuals who: were men, were older than 50 years of age, were living alone, had a history of psychopathology pre-injury, presented more physical health problems, were unemployed, were single, and had an Axis I diagnosis at 24 months post-injury. Furthermore, it was expected that social support scores at 4-months would contribute to predict the presence of mental health disorders 12-24 months post-injury. These time points were selected because at 4 months post-injury, prevention interventions are still possible as many persons still receive rehabilitation services, and at 24 months the majority of patients are expected to be back in the community.

Methods

Participants

Participants were adults aged 18-65 years having suffered a mild to severe head injury and who were hospitalized at a Level I trauma center in the province of Québec (Hôpital de l’Enfant-Jésus and Montreal General Hospital). They were recruited between December 2013 and October 2016 and followed up for two years (until November 2018). Patients were excluded if they had a history of neurological disorder (e.g. moderate or severe TBI, stroke, brain tumour, multiple sclerosis), concomitant spinal cord injuries, were unable to understand written or oral material (as a result of cognitive or language impairments or if not speaking either English or French), or were unable to provide informed consent because of marked cognitive issues (as determined by an attending health professional).

Procedure

A research nurse was appointed to approach participants or their respective family members upon admission, should they be eligible to participate in the study. If the nurse obtained verbal consent, an information pamphlet about the study was provided and potential participants were informed that the research team would be in contact with them at a later date.