© Jérôme Deschênes, 2019

Governance and Corporate Social Performance (CSP):

The role of individual board directors and institutional

investors

Thèse

Jérôme Deschênes

Doctorat en sciences de l’administration - comptabilité

Philosophiæ doctor (Ph. D.)

Governance and Corporate Social Performance

(CSP)

The role of individual board directors and institutional

investors

Thèse

Jérôme Deschênes

Sous la direction de :

iii

Résumé

Cette thèse présente une étude de la relation au niveau individuel entre, dans un premier temps, les administrateurs indépendants et la performance sociétale des entreprises (CSP) ainsi que, dans un second, les investisseurs institutionnels et cette même performance. Le réel pouvoir et l’impact véritable des administrateurs sur la performance d’une entreprise sont depuis longtemps sujets de débats. Cette discussion est d’autant plus vive lorsqu’il est question des administrateurs indépendants. Afin d’ajouter à cette question fondamentale, je considère une mesure de performance non financière : la CSP. Je m’interroge sur l’existence d’une affinité entre les administrateurs indépendants et la CSP. J’utilise des données concernant les administrateurs américains et des pointages de performances sociétales (globales, environnementales et sociales) pour les années 1999 à 2014 (inclusivement). En utilisant un effet fixe à deux niveaux (pour les entreprises et les administrateurs), je mets en lumière une association entre les administrateurs indépendants et la dimension environnementale de la CSP. Cependant, j’observe également que cette relation est beaucoup plus faible que pour les administrateurs internes. Dans un deuxième temps, je relie les caractéristiques individuelles des administrateurs indépendants aux effets fixes obtenus précédemment. Ce deuxième test me permet de mettre en relief le fait que les caractéristiques observables des administrateurs indépendants expliquent une très faible part de l’association entre ces individus et la CSP. Ce résultat souligne le fait qu’utiliser des attributs observables, comme c’est souvent le cas dans les écrits scientifiques, pourrait ne pas être suffisant pour étudier adéquatement la relation entre des individus et certaines mesures de performance. En revanche, la méthode utilisée dans cette thèse permet de prendre en compte à la fois des caractéristiques observables et non observables des administrateurs indépendants.

Je m’intéresse également aux agissements des investisseurs institutionnels en ce qui concerne la CSP des sociétés qu’ils possèdent ou de celles qu’ils convoitent. Je teste d’abord l’intérêt des investisseurs envers la CSP. Ma mesure de détention de titres est la proportion de la valeur totale déclarée de fonds alloués à une entreprise donnée par un investisseur institutionnel. À l’aide d’un effet individuel (analogue à un effet fixe), je vérifie si les investisseurs institutionnels s’intéressent à la CSP au niveau individuel, ce qui est le cas pour certains. Ensuite, je me penche sur les deux hypothèses de base proposées par Hirschman (1970) en ce qui concerne les investisseurs institutionnels et leur capacité à obtenir un niveau de performance non financière déterminée : (1) ils peuvent acheter des actions et en vendre (ainsi, ils votent avec leurs pieds) ou (2) ils peuvent tenter d’influencer la direction de l’entreprise par l’entremise de discussions (in)formelles (l’approche vocale). J’observe que les investisseurs institutionnels, en tant que groupe, adoptent les deux méthodes. Cependant, certains ayant des besoins précis pour une composante spécifique de la performance choisissent l’une des deux méthodes.

iv

Abstract

This thesis presents an individual level investigation of, on one side, the link between independent directors and corporate social performance (CSP) and, on the other, the association of institutional investors to, again, CSP.

The real power and the genuine impact of directors on the performance of the firm have always been subject to a lot of discussion. This is even truer with independent directors. To give insight into this fundamental question, I look at a non-financial performance metric: the CSP. I investigate whether there is an individual a priori regarding CSP issues by independent directors. I use directors’ data for US firms in the 1999–2014 period as well as CSP scores (global, environmental and social). By using a two-way fixed effect for both firms and directors, I discover that there is an association between individual independent directors and the environmental dimension of CSP. However, I uncover the fact that this association is considerably weaker than the relation between inside directors and CSP. In a second set of tests, I link individual attributes to the independent directors fixed effects obtained before. In this second regression, I uncover the fact that observable characteristics of independent directors account for a very small part of the association of individuals to CSP. It underlines the fact that using observable characteristics, as it is often done in the literature, might not be sufficient to uncover the fundamental association between individuals and a given performance metric. However, the method used here accounts for both observable and unobservable characteristics of independent directors.

I also investigate the behaviours of institutional investors when it comes to attain a specific CSP from the firms they are invested in or plan to invest in. As an investor-level ownership measure, I compute the proportion invested in a firm over the total declared assets of an institutional investor. By computing individual institutional investor effects (similar to fixed effects), I first test whether institutional investors care about CSP, which some do. I then test the two basic hypotheses proposed by Hirschman (1970) when it comes to institutional investors' ability to obtain a given level of non-financial performance: (1) they can either sell or buy shares (the feet approach) or (2) they can try to influence the executives by having (in)formal discussions (the voice approach). I estimate my individual effect in two ways: observing the shareholding variable prior or after collecting the CSP score of a firm. I find out that institutional investors as a group adopt both approaches. Nevertheless, a fair portion of them seems to choose only one (often the feet approach) according to their need in CSP.

v

Table des matières – Table of contents

Résumé ... iii

Abstract ... iv

Table des matières – Table of contents ... v

Liste des tableaux – Table of tables ... vii

Liste des figures – Table of figures ... viii

Liste des abréviations – Table of abbreviations ... ix

Remerciements – Acknowledgments ... xi

1 Introduction ... 1

2 Literature Review and Hypotheses ... 9

2.1 Corporate Social Performance ... 9

2.2 Board of Directors and CSP ... 12

2.2.1 Board Level Variables ... 17

2.2.2 Directors Characteristics at Board Level ... 22

2.2.3 Conclusion ... 27 2.3 Institutional Investors ... 29 2.3.1 Conclusion ... 34 2.4 Hypotheses Development ... 35 2.4.1 Independent Directors... 36 2.4.2 Institutional Investors ... 38

3 Corporate Directors and CSP ... 41

3.1 Methodology ... 41

3.1.1 Measuring Corporate Social Performance ... 41

3.1.2 Directors’ Individual Effect ... 42

3.1.3 Directors’ Personal Characteristics ... 45

3.1.4 Sample ... 46

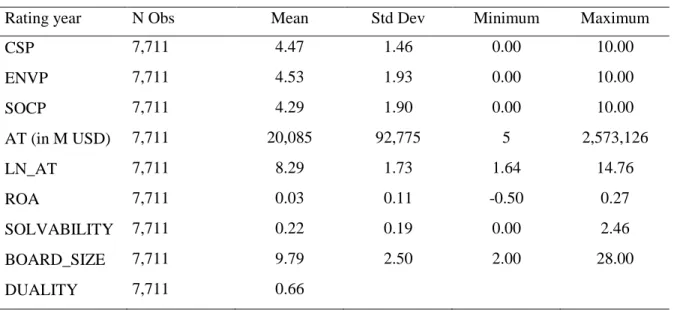

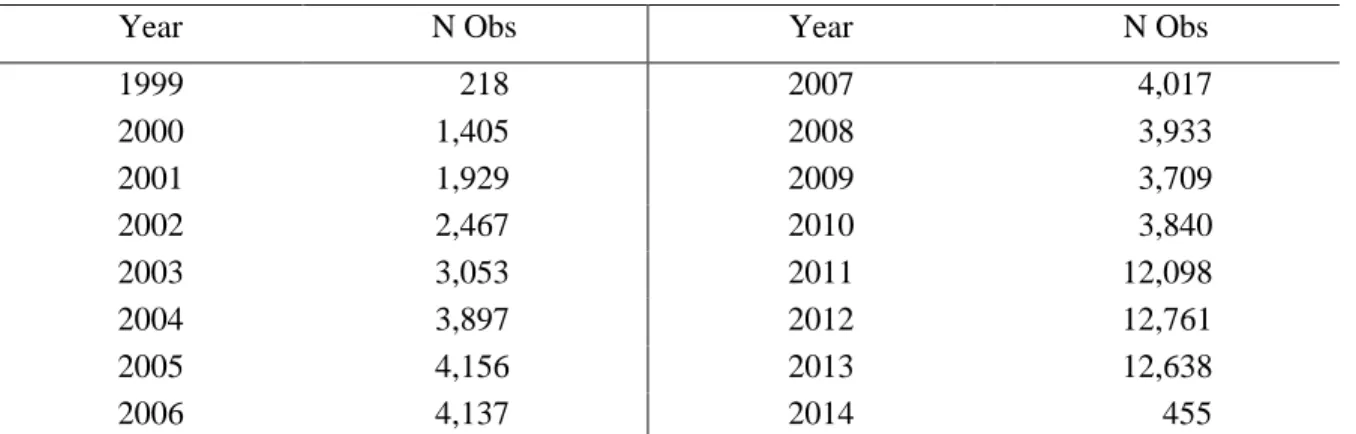

3.1.5 Descriptive Statistics ... 48

3.2 Main results ... 49

3.2.1 Independent Directors’ Role in CSR ... 49

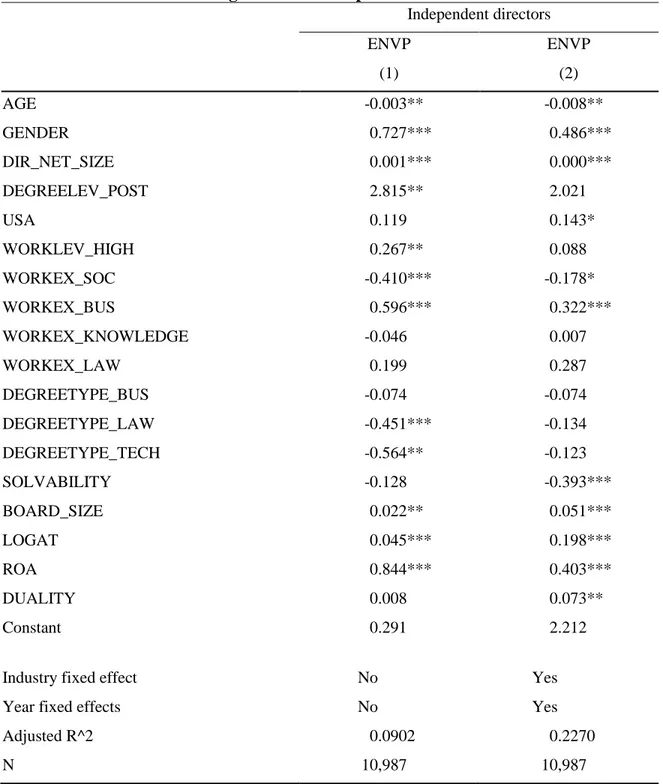

3.2.2 Independent Directors’ Characteristics and Fixed Effects ... 51

3.3 Supplemental analyses ... 59

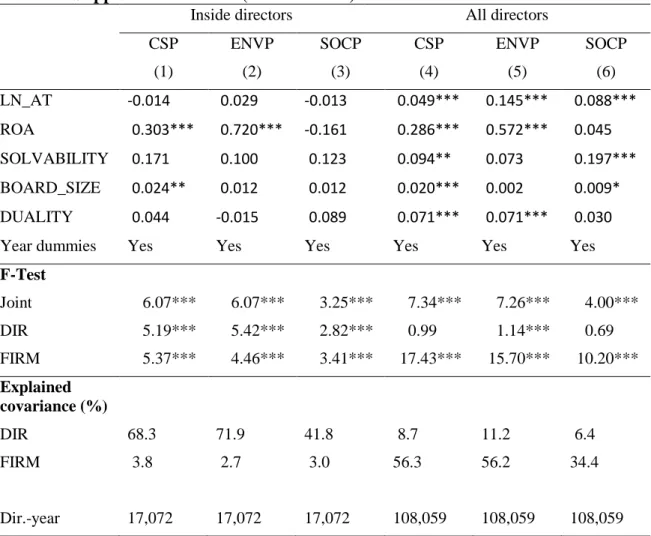

3.3.1 Inside Directors’ Role in CSP ... 59

3.3.2 Moving Director Method ... 62

3.3.3 Analysis by Periods of Directors’ Individual Effects ... 66

3.3.4 Centrality Measures ... 67

3.4 Summary ... 68

4 Institutional Investors and CSP ... 69

4.1 Methodology ... 69

4.1.1 Design and Models ... 69

4.1.2 Variables ... 73

vi

4.1.4 Descriptive Statistics ... 77

4.2 Main Results ... 80

4.3 Supplemental Tests ... 88

4.3.1 Institutional Investor Characteristics ... 88

4.3.2 Analysis by Periods of Individual Investors’s Effects ... 94

4.3.3 OLS Regression ... 97

4.4 Summary ... 98

5 Conclusion ... 99

Appendix A – IVA assessments ... 103

Appendix B – The AKM Method ... 104

Appendix C – Variable description ... 105

Appendix D – Full Correlation Tables Between Voice and Feet γ Coefficients ... 109

Appendix E – Factor analysis statistics ... 113

vii

Liste des tableaux – Table of tables

Table 3.1: Descriptive statistics for the independent directors fixed effects model ... 47

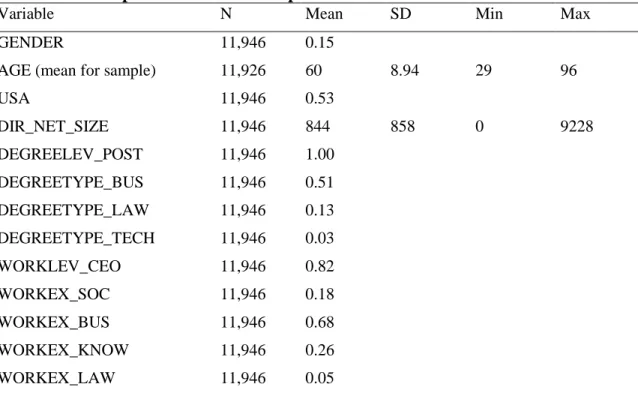

Table 3.2: Descriptive statistics of independent directors’ characteristics ... 49

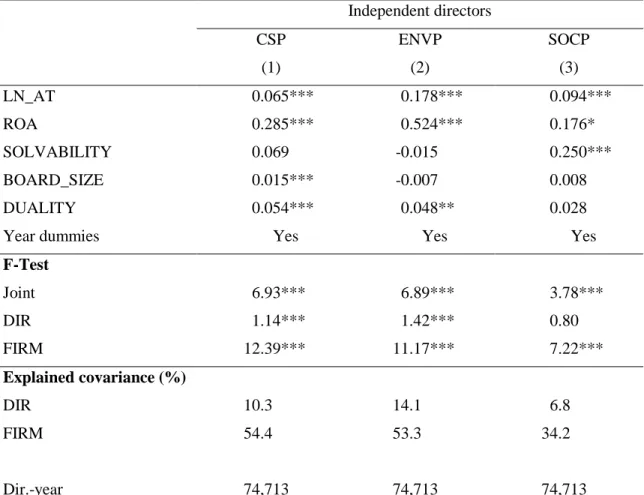

Table 3.3: Test of independent directors fixed effects ... 51

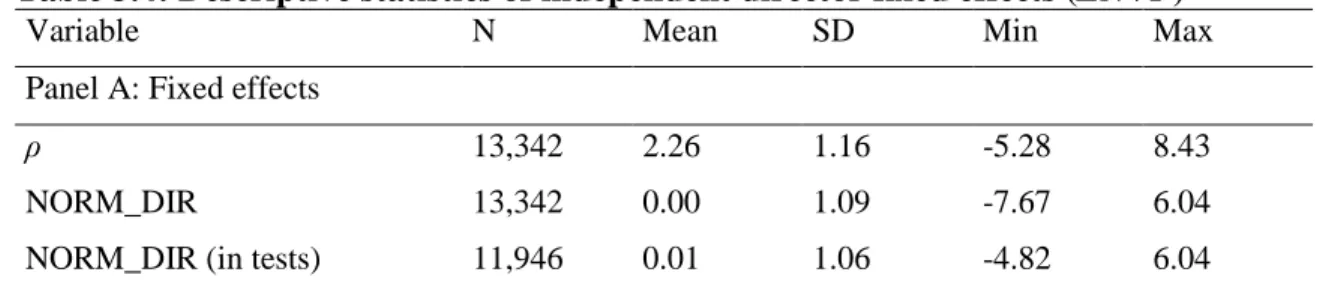

Table 3.4: Descriptive statistics of independent director fixed effects (ENVP) ... 52

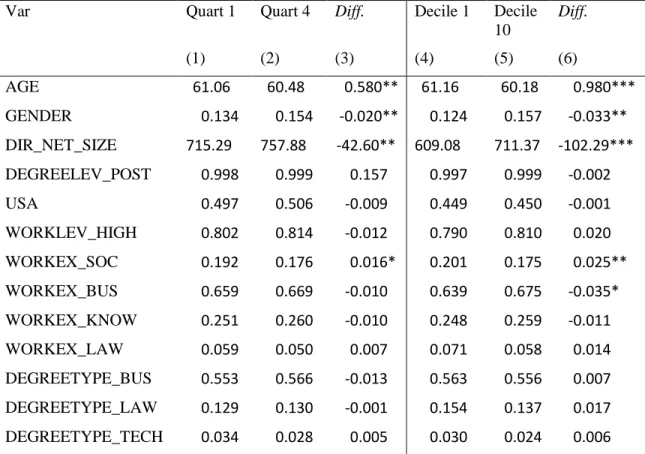

Table 3.5: Two-sided T-tests of mean differences of independent directors' characteristics ... 54

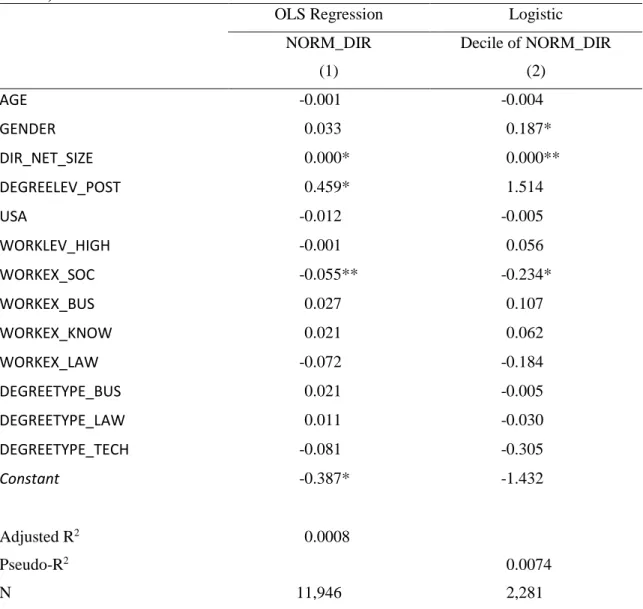

Table 3.6: Regressions of independent directors’ characteristics and fixed effects (ENVP) 56 Table 3.7: Board level OLS regressions of independent directors’ characteristics ... 58

Table 3.8: Supplemental tests of (inside and all) directors' fixed effects ... 60

Table 3.9: Regressions of inside directors’ characteristics and fixed effects (ENVP) ... 62

Table 3.10: Tests of independent (and all) directors' fixed effects for moving directors ... 64

Table 3.11: Characteristics of independent directors by moving type (movers vs non-movers) ... 65

Table 3.12: Test of independent directors' fixed effects – by periods ... 67

Table 4.1: Sample selection process for institutional investors-firm-year observations ... 77

Table 4.2: Descriptive statistics for institutional investors... 78

Table 4.3: Individual institutional investors effect regressions ... 81

Table 4.4: Descriptive statistics of the coefficients for individual institutional investors ... 84

Table 4.5: Correlations between coefficients of individual institutional investors ... 86

Table 4.6: Two sample tests on dummy variables of coefficients of individual institutional investors ... 87

Table 4.7: Institutional investors' characteristics ... 91

Table 4.8: Relation of the characteristics of institutional investors with γ coefficients ... 93

Table 4.9: Individual institutional investors effect regressions – by subperiods... 95

Table 4.10: OLS regressions for institutional investors ... 98

Tableaux en annexe – Tables in appendices Table C.1: Description of variables for directors ... 105

Table C.2: Description of variables for institutional investors ... 107

Table D.1: Correlations of fixed effects variables ... 109

viii

Liste des figures – Table of figures

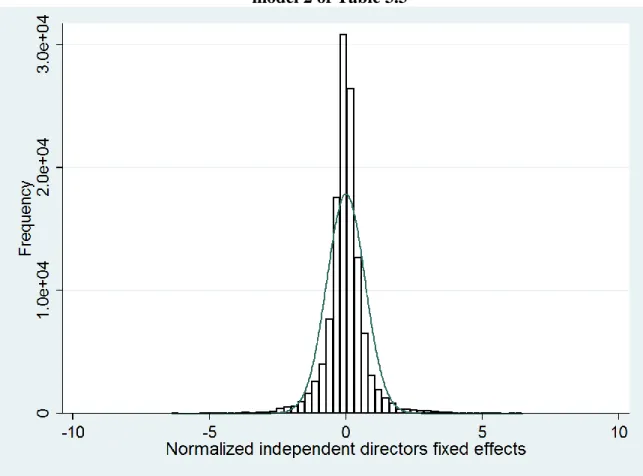

Figure 3.1:Distribution of ENVP individual fixed effects (DIR) as estimated in model 2 of Table 3.3 ... 53 Figure 4.1: Timing of data collection for the Voice setting ... 70 Figure 4.2: Timing of data collection for the Feet setting ... 71 Figure en annexe – Figures in appendices

ix

Liste des abréviations – Table of abbreviations

Abbreviations1 Meaning in this thesis

CSP Corporate Social Performance CSR Corporate Social Responsibility SOX Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 US(A) United States (of America)

UNPRI United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible Investment SRI Socially Responsible Investing

MSCI Morgan Stanley Capital International

IVA Intangible Value Assessment (a Corporate Social Performance database provided by Morgan Stanley Capital International)

KLD Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini Research & Analytics (a Corporate Social Performance database provided by Morgan Stanley Capital

International)

EMS Environmental Management System ROA Return on Assets

USD United States Dollars (a currency)

AKM Abowd, Kramarz, and Margolis (authors of 1999 article of a method for assessing individual effects)

MDM Moving Director Method (a method for assessing individual effects)

x

À travers les autres, nous devenons nous-mêmes. (Lev Vygotski)

xi

Remerciements – Acknowledgments

Ma première rencontre avec celui qui allait devenir mon directeur de recherche fût très révélatrice de la relation qui nous attentait. En effet, en ce tiède matin de juin, Jean et moi sommes arrivés simultanément au support à vélo pour y verrouiller nos montures respectives en nous adressant quelques mots, et ce, sans savoir que nous devions nous rencontrer quelques minutes plus tard. Cette passion pour les activités sportives extérieures aura été un lien qui aura su ponctuer nos échanges pédagogiques et personnels. Ces moments de discussions informelles favorisaient évidemment un climat de travail et une relation harmonieuse. Au cours de ces 5 années, j’ai appris à connaître un professeur qui ne compte pas les heures de travail, qui est disponible pour ses étudiants et, peut-être surtout, qui sait tabler sur les forces de ses étudiants (les technologies de l’information par exemple) tout en les aidant à surmonter leurs défis (on peut penser aux revues de littérature notamment). J’aurais aimé comprendre plus tôt dans mon cheminement à quel point l’appui d’un directeur de recherche peut faciliter le travail, tant d’heures perdues dans le doute et dans l’inaction auraient été bien mieux rentabilisées. En somme, je n’aurais pu demander d’apprendre le métier de chercheur avec une autre personne. Merci, Jean pour l’encadrement et le soutien. Je vous souhaite une bonne fin de carrière bien remplie, mais, plus important encore, bien des années de ski de fonds et de vélo.

Cette rencontre ne serait jamais survenue si ce n’était de Mme Marie-Josée Roy, ma directrice d’essai à la maîtrise. C’est par elle que, d’une part, mon appétit pour la recherche s’est développé et, de l’autre, que l’idée d’entreprendre des travaux doctoraux sous la supervision de Jean est apparue. Il va sans dire que cet apport a été déterminant, mais je tiens surtout à la remercier de son support ponctuel qui ne manquait jamais de me lancer sur un nouvel élan.

Merci à Mme Michelle Rodrigue et à Mme Marie-Claude Beaulieu pour l’évaluation juste de mon travail.

Je tiens également à souligner l’encadrement et le soutien de tout le personnel de l’École de comptabilité. Évidemment, Messieurs Gendron, Henri et Brousseau ont été centraux dans le développement de ma connaissance de la recherche en comptabilité. Ce fut très important pour moi qui suis, et serai toujours, un non-initié. D’ailleurs, Carl pourrait se voir décerner le titre de codirecteur honorifique tellement j’ai profité de son savoir et de son écoute pour faire évoluer mon travail. Parfois les discussions étaient techniques (centrées sur la méthodologie et sur les articles pertinents), mais, le plus souvent, nos échanges s’ouvraient sur la politique, la gestion de la carrière universitaire et divers autres sujets connexes. Il est véritablement l’exemple parfait du professeur dont la porte est toujours ouverte (au sens propre, comme au figuré). Merci à MM. Maurice Gosselin et Jean-François Henri de m’avoir accordé leur confiance et de m’avoir assigné des tâches d’enseignement, ce sera très utile pour la suite des choses, du moins, je l’espère. Même si je n’étais qu’un doctorant, Claire-France (dont les succès de chercheuse continueront longtemps de m’impressionner), Christine (dont le bureau est un havre de paix) et Louis-Phillipe (qui me démontre que je ne suis pas le seul à avoir des projets – trop – ambitieux) m’ont accueilli comme un des leurs. Leur franche camaraderie a favorisé mon intégration à l’École, mais, et c’est le plus important, ont été des soupapes importantes quand les choses ne tournaient pas comme je le souhaitais. Un enseignant au collégial avait dit en classe que la bière est le deuxième moteur

xii

le plus important de la science après le café, je pense maintenant qu’il avait raison. Je ne pourrais passer sous silence le plaisir que j’ai eu à étudier avec Cynthia et Steeve durant ma scolarité. Les cours étaient vivants et enrichissants grâce à eux.

D’un point de vue personnel, je voudrais souligner l’importance d’avoir des parents qui croient plus à toi que tu ne le fais toi-même. Jamais, durant ma longue et erratique carrière d’étudiant, ils n’ont cessé de m’encourager. Les deux sont de vrais beaux exemples de persévérance. Tout ce que je suis aujourd’hui, c’est à eux que je le dois. Un remerciement tout spécial à ma sœur et toute sa petite famille pour le simple bonheur que j’éprouve à les côtoyer.

Et que dire de Marie, bien que trop souvent je crusse qu’elle m’entrainait dans l’« oisiveté », il semble que ce dosage important entre vie personnelle et vie professionnelle m’a, au bout du compte, été plus bénéfique que je ne le croyais. Ce sont nos passions communes qui m’ont permis de persévérer au quotidien : nos petits soupers tardifs, nos nombreux voyages, nos activités sportives et, tout simplement, le temps de qualité passé ensemble. Sur une note un peu plus émotive, à la suite de mon accident, tu as été celle qui était auprès de moi sans relâche pour me remettre le plus rapidement possible sur « mes deux pieds ». Sans cette guérison du corps et de l’âme, ce doctorat n’existerait pas. Grâce à toi, je suis remonté à vélo avant de pouvoir remarcher, c’est dire à quel point tu as été déterminante dans la suite des choses.

Thanks to all the staff of the Accounting Group at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) for their warm welcome. Especially to: Professor Stephen Taylor who made my visit possible on a very short notice, Judith Evans for all the marvellous administrative work she has done for me, and to Jin for the fun time at school and elsewhere. Thanks to everyone who attended the presentation of my paper for your very useful comments. I will never forget this pleasant visiting student experience, it has exceeded my expectations in every way.

Parlant de l’Australie, un remerciement particulier à Maude et Nicolas qui m’ont accueilli chez eux à Sydney. Nicolas est un colocataire exemplaire, il a su me faire sentir chez-moi, chez-lui. Pour ce qui est de Maude, son appui a toujours été apprécié que ce soit de l’autre côté de la terre ou, ici, à l’École. Avec ton retour parmi nous, il nous reste seulement qu’à célébrer la fin d’une étape et le début d’une autre!

Enfin, le soutien économique de l’Autorité des marchés financiers du Québec (AMF) par son Programme d’excellence ainsi que de la Chaire de recherche en gouvernance de sociétés de l’Université Laval a rendu possible l’accomplissement de ce travail.

1

1 Introduction

The object of quantitative business sciences has largely been the economic performance of the firms. This is indeed legitimate considering that this is the prime reason for their existence. Nevertheless, events in the recent years have changed this. We can think of financial scandals such as the Enron fraud and the subprime mortgage crisis, as well as of environmental incidents like the Deepwater Horizon platform oil spill and the dishonest Diesel car emissions by the VW Group (as well as more complex situations like climate changes). Consequently, socially acceptable behaviours of firms have become an important subject in the public space, general media and scientific literature.

This also leads to a greater pressure on firms to move toward a better corporate social performance (CSP). While, not too long ago, the task of managing stakeholders’ expectations was mainly the task of operations’ executives for the environment and the marketing department or the legal team for the community, it is now of common knowledge that the genuine implication in corporate social responsibility generally needs to be driven by decisions at the upper echelons of a firm (Chin et al., 2013). CEOs and the other executives are naturally the prime source of such choices. However, in the publicly traded firms, there are governance mechanisms in place to oversee those choices. The board of directors has this important responsibility. Since the Sarbanes and Oxley Act (SOX), independent directors have a noteworthy role in the boardroom (Duchin et al., 2010). Also, they now account for 80% of the board members while they were a mere 20% in the 1950s (Gordon, 2006). Since they are elected by shareholders, their decision-making process should take into account even more the needs of those owners (Petra, 2005; Nguyen and Nielsen, 2010). In addition, shareholders are able by themselves to promote their interests. Institutional investors are generally seen as shareholders with the capacity to have significant impact on firm they own (Hirschman, 1970; McCahery et al., 2016).

To illustrate the possible impact of independent directors and institutional investors on CSP, I present two recent anecdotal evidence. In the aftermath of the VW emission scandal, many experts are questioning the effectiveness of the board in monitoring CEO’s environmental decisions and even stating that the main problem was in fact in the boardroom (Bryant and Milne, 2015; Stewart, 2015). The structure of the VW Group board itself has been described

2

as too complicated to be effective on most matters. The board was composed of four groups: (1) close friends and family members – including CEO’s fourth and current wife – appointed by the executives, (2) government officials, (3) a major investor’s employees and (4) workers’ representatives. This structure had important impacts. Most of the discussions at board level were related to the stabilization of the size of the workforce as it was the main interest of both the local governments and unions. Consequently, other stakeholders’ points of view were completely absent. In these circumstances, the CEO and its executive team had all the latitude needed to prepare what we now know as one of the largest environmental scandals in history. Indeed, Germany corporate laws are different from US ones. However, this represents how a board with major structural flaws can lead to serious complications.

The implication of institutional investors in CSP is likewise worth noting. Some institutional investors (like pension plans) have obligations instituted by their constituents, but also voluntarily subscribe to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI) or create funds that follow Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) strategies. Moreover, investors themselves claim to consider CSP when investing. For instance, the CEO of BlackRock (the World’s largest institutional investor as of 2018) explicitly stated that “[a]s a fiduciary, BlackRock engages with firms to drive the sustainable, long-term growth that our clients need to meet their goals” (Fink, 2018).

This three-way relationship (between executives, independent board members and institutional investors) implies that, even if the executives have most of the faith of a firm in their hands, they nevertheless need to consider the inputs of other governance mechanisms. In this context, I will look at independent directors’ and institutional investors’ relationship to CSP.

In the literature researchers usually study the impact of boards on CSP, to do so, they gather information about some variables at board level and try to associate them with the global CSP of a firm. For instance, they study corporate governance variables such as gender (Krüger, 2009; Bear et al., 2010; Boulouta, 2013; Hafsi and Turgut, 2013; Zhang et al., 2013), director independence (Johnson and Greening, 1999; Van den Berghe and Baelden, 2005; Harjoto and Jo, 2011; Hafsi and Turgut, 2013; Zhang et al., 2013) or board diversity. They then look at the presence or at the proportion of those variables at board level. Studying

3

individual impact by using this approach relies on an outline of individual characteristics at board level. Most of all, this method cannot account for unobservable characteristics of these directors (or board).2

As for institutional investors, researchers by their methodologies mostly answer the question: are firms with some level of CSP more (or less) owned by institutional investors? To answer this question, most researchers link CSP to firm level institutional ownership. Hence, it is assumed that firms facing institutional ownership will behave in a common way. This should be true only if, on average, institutional investors request a similar level of CSP. However, some institutional investors might look for a better CSP while others may not be interested in this type of performance at all. Consequently, before testing the relation between CSP of a firm and its institutional shareholding, one needs to assess this potential consensus among investors. Yet, results from prior studies are mixed. Using this methodology, some researchers finds a positive relationship (Wahba, 2008; Hong and Kacperczyk, 2009; Saleh et al., 2010; Chava, 2014), others find a negative one (Fernando et al., 2010; Gillan et al., 2010), Harjoto et al. (2015) uncover a non-linear association, and others find no relation at all (Barnea and Rubin, 2010).

For both independent directors and institutional investors, researchers examine the relation of uniform groups of governance actors to CSP. The groups are based on common characteristics (if they exist). This does not account for unobservable characteristics and the variability of behaviours among a given group. Accordingly, I propose to investigate both relationships at individual level in this thesis. Therefore, my general research question is: Do CSP matters for individual governance actors (namely independent directors and institutional investors)? I investigate whether there is an intrinsically individual a priori regarding CSP issues. I am not asking if CSP matters for the firm, its value or its stakeholders but rather if it matters to independent directors or institutional investors. If one wants to know if CSP is

2 Moreover, it does not tell how a firm looking for a specific CSP should balance the characteristics known to be related to this level. For instance, if having greater diversity (Bear et al., 2010) is related to a better CSP, then how much of such diversity is necessary to obtain the desired performance? Is having one member with all the diversities characteristics concentrated in him sufficient? Are those characteristics always complementary (i.e.: adding one more always gives better performance)? Or, are they sometimes substitutes to one another? Problems like these are nevertheless rather difficult to solve and might be just not answerable at all.

4

a prominent issue for a firm, s/he must consider the involvement in such matters of the major actors in the corporate world. Later in this introduction, I develop specific research questions for each group. The following paragraphs deal with independent directors.

The real power and the genuine impact of directors on the performance of the firm have always been subject to a lot of discussion. The agency theory and the legal environment of businesses teach us that board members’ priority should be the economic interest of shareholders. The prime interest of shareholders is the wealth preservation and accumulation. However, in the literature, it is not clear if independent directors, as a group, have an effective positive impact on a firm's performances. This ambiguity is even truer at individual level. So, I introduce a tension by taking a step backward to revise the assumption that independent directors have an individual impact on firm performances. Furthermore, CSP being in large discretionary, firms and/or individuals might seek a positive CSP or simply do not care about this type of performance. Hence, this leave even more room to observe the variability among independent directors (even those sharing common observable characteristics).

First, a board is not a monolithic entity. In fact, directors have diverse backgrounds, distinct roles and, probably, diverging aspirations. Individual independent directors will try to push forward their CSP targets at board level or to choose board that suit those targets. This leads to their capacity to obtain, as individuals, a specific level of CSP and for the researcher to observe this leaning.3 Hence, the interest for an individual level study. In fact, this approach has been used to explicitly examine the impact of individual executives (Demerjian et al., 2012a; Demerjian et al., 2012b; Graham et al., 2012).4

Second, selecting some board composition variables or board characteristics and trying to correlate them to the CSP of a firm is implicitly accepting that directors do indeed have an impact on CSP. It is possible, however, that CSP is a firm attribute that is driven by factors which are not in the hands of the board. Testing it at board level might be of some interest

3 Even within the same firm with virtually only unanimous decisions taken (and enacted), not all the board members are totally agreeing on all the subjects brought to them. This supposes that there might be some not observable diverging points of view at individual level by (1) entire board’s decisions and (2) aggregated board level characteristics. However, those divergent points of view are not reflected in the CSP of a firm making it difficult to study.

5

but the effect of the executive members of the board might not be ruled out. Accordingly, measuring the marginal effect of each board member might shed new lights on the question. It is only after assessing this real impact (again, if any) that some sort of characteristics should come up to help portray the directors who have such impact. Put simply, the first specific research question is (Bertrand and Schoar, 2003): Does a firm’s CSP matters for individual independent directors? This way of phrasing the question is different in two main ways: (1) obviously the level of analysis is taken deeper to the individuals sitting on a board, and (2) there is an absence of belief that individual independent directors, as a group, are related to a general level of CSP. A second research question naturally arises if a relation is effectively uncovered when answering the first research question: Are directors’ “CSP-style” associated with observable directors’ characteristics?

To answer my first specific research question, I study independent directors from the US-listed firms in BoardEx North America for the 1999–2014 period. From the MSCI IVA dataset, I use the environmental and social scores as well as a third aggregate score build from both components (computed using their respective weights in IVA). I use a two levels fixed effects model with directors’ and firms’ effects. The concept behind this evaluation method is that if a director has some influence, s/he will have it despite the firm effect which should be the main driver of CSP. My approach takes advantage of the Cornelissen (2008) algorithm to compute the individuals fixed effects as well as the firm fixed effects. In so doing, I find that individual independent directors are associated with the environmental component of CSP and the aggregate score. That said, they are not related to the social component. However, this association between independent directors and CSP is not as important as that of the firms as illustrated by the much larger proportion of covariance explained by the firm fixed effects (from 34% to 56%) than by the individual directors’ effects (from 9% to 12%).

To further investigate the above results for the first specific research question, I run some supplemental tests. To assess the size of the effect, I rerun the same test but this time for the inside directors and the whole sample (inside, grey and independent directors). Mainly, I find that the relation between CSP and directors is far stronger with the inside directors (as expressed by a higher covariance explained by the director fixed effects) than for the

6

independent directors. The same relation is somewhat more powerful for all the directors (insiders and independents) again compared to the independent directors taken alone. Using the alternative method of the moving directors to compute the fixed effects, I also measure the impact of solely the moving independent directors. Results are similar, with a greater explained variance for the moving directors compared to the whole sample of independent directors. This latter method is more common in the individual contribution literature (Graham et al., 2012).

To address the second specific research question for independent directors, I examine the link between a set of individual characteristics (age, gender, social network size, work experience, highest level of degree and type of formal education) and the directors-fixed effects. Only director’s network size and work experience in the community are related to the fixed effects. However, the R-squared of all estimated models are near or below 1%. It is quite clear that even with some significant characteristics, there are plenty of individual specificities remaining that are not accounted for in the models. In the next lines, I now focus on institutional investors.

Nowadays, institutional investors are important in the American stock market (and many other markets around the world). For instance, as much as 60% of all shares in the United States (US) were held by institutional investors in 2011, up from a maximum of 16% in the mid-sixties (Çelik and Isaksson, 2014). They are also considered a special form of investors mainly by the size of their investments and assets, but also because they are viewed as more sophisticated investors (Edelen et al., 2016) that are able to produce or obtain for themselves better information about stocks and firms (Chemmanur and He, 2016).

Godfrey et al. (2009) propose that investing in CSR-oriented firms produces an insurance-like effect against unforeseeable social and environmental wrongdoing by firms that might impair returns of their stock. Harjoto et al. (2015:4) add that “CSR helps the firm secure critical resources controlled by various stakeholders.” This control helps firms keep their business’s advantages among their peers. This concept is important for any investors. Nevertheless, institutional investors often have longer investments’ horizons. Also, it is more difficult (for legal, contractual or financial reasons) for them to exit the shareholding of firms,

7

making them more exposed to potential mid to long-term threats.5 In addition, institutional investors (who are often intermediary investors) sometimes use CSP driven investments as a marketing point to drag more money into their portfolios. I also observe in the literature that most researchers suppose homogeneity (or at least some sort of informal coordination) in the actions of institutional investors. Elsewhere in the literature, researchers use the legal categorization (as defined by the mandatory 13F filling by the US legislator) as a proxy for differences among institutional investors. This classification is considered insufficient to account for the wide array of different strategies even among those categories. Moreover, the information about institutional investors is scarce which makes it difficult to unveil their critical characteristics. I believe that, in this context, an individual level analysis might be the best way to account for the great variability among institutional investors. This leads to a research sub-question: (Bertrand and Schoar, 2003): does CSP matters for individual institutional investors?

My primary sources of data are Thomson Reuters Institutional (13F) Holdings database for the institutional holdings and the MSCI Intangible Value Assessment (IVA) ratings for my CSP measures. Using these two databases, I perform an individual institutional investor level analysis. The aggregate CSP, environmental and social scores from IVA for firms in the portfolio of an institutional investor are my dependent variables while I use the proportion of the portfolio of an institutional investor allocated to a firm as my independent variable. By looking at the institutional holdings at investor level instead of at firm level, I am able to observe the behaviour of institutional investors directly (if they invest or disinvest in a particular firm) by creating an individual coefficient for each institutional investor. I then analyze this coefficient. I find that individual independent directors are associated with the environmental and social component of CSP as well as with the aggregate score. This association is relatively weak though. The variance explained by individual investors effects is always lower than two percent using either of my three CSP measures while it ranges from 44.2% to 61.9% for the firm fixed effects.

5 I am describing risks harming specifically the wealth of institutional investors by the behaviours of the firms they own. However, institutional investors can also see their legitimacy reduced by being systematically associated with firms with a bad CSP.

8

As described by Hirschman (1970) in his seminal work, institutional investors have basically two ways to have their voices heard by firms: (1) they can simply vote with their feet by leaving the firm shareholding as well as buying shares of firms fitting their needs or (2) they can engage in a discussion process with the firm. Both methods have advantages and disadvantages. In fact, most institutional investors report that they use these two mechanisms when it comes to corporate governance requests (McCahery et al., 2016). Hence, my second research sub-question is: Do institutional investors uses the voice or exit method (or both) to obtain a specific level of CSP?

To distinguish between two mechanisms used by institutional investors to attain their desired CSP level, I use: (1) one year of lagged ownership to account for the possibility that institutional investors have to interact with the firm to influence it CSP (voice approach) or (2) one year of lagged firm’s CSP to account for the availability of the performance prior to the investment (feet approach). I obtain individual effects with both models. I find that institutional investors use the buy and sell strategy (feet approach) as well as the dialogue with the leaders of the firms they are invested in (voice approach). The results depend of the component of CSP studied. While both strategies are observed, there are more institutional investors choosing the feet approach. The level (low or high) and the type (environmental or social) of CSP performance required by an investor drive the choice of the approach. The feet approach seems to be more appropriate for the environmental performance while the voice approach is more suitable for the social component of CSP.

The rest of this document is organized as follows. In the next section, I first examine the literature and detail my hypotheses. Then, I present the methodology and the results for the association between independent directors and CSP in the third section. The fourth section contains the method and the empirical findings for the institutional investors’ relation to CSP. In the closing section, I offer some concluding remarks, including this thesis’s contributions and some future research propositions.

9

2 Literature Review and Hypotheses

In this literature review chapter, I first define the concepts of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate social performance while emphasizing on the relationship between governance and ethical corporate citizenship. Second, I outline the reasons and the mechanisms underlying the role of the board in CSP. The same is done for institutional investors in a third time. Fourth, I present the literature linking individuals to CSP. A concluding section describes and justifies the main hypothesis.

2.1 Corporate Social Performance

In this section, I define the concept of corporate social performance (CSP). First of all, one must understand the broader concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) before exploring the concept of CSP. Put simply, CSR is the process by which a firm aims for a better CSP (which is the observable outcome of this process). As Ingley (2008:19) observes it: “The terms used, sometimes interchangeably, to describe CSR include business ethics, corporate citizenship, corporate accountability and sustainability. Definitions and interpretations of these concepts range from a basic level of engagement to the most demanding degree of commitment, system-wide.” Therefore, the CSR acronym has a wide variety of significations in the literature (Carroll, 1999; Moir, 2001; Aguinis and Glavas, 2012). Dahlsrud (2008) identifies 37 definitions of the term CSR in his literature review. His analysis leads to the identification of five fundamental dimensions of CSR that are common to most definitions: the emphasis on stakeholders, the social component (which is related to the people at large), the economic component (as CSR actions must be sustainable for the business model of a firm), the voluntary nature, and the natural environment component. From the work of Dahlsrud (2008), one could argue that CSR is the way firms integrate their economic, social and environmental responsibilities into their business’s actions (even if there is not a unique and universal understanding of the concept). In this thesis, I use this latter definition.

As it is the case for CSR, CSP (the outcome concept) is not uniformly defined in the literature. For instance, early on, Wood (1991:693) sees CSP as: “a business organization’s configuration of principles of social responsibility, processes of social responsiveness, and policies, programs and observable outcomes as they relate to the firm’s societal

10

relationships.” This description seems to integrate both CSR and CSP. A more recent definition by Oikonomou et al. (2017:2) is more restrictive: “The term CSP is usually used to capture the outcome-based measurement of a firm’s stance toward CSR-related issues.” Nonetheless, the common ground between both definitions is that, while CSR is more centred around corporate behaviours as described above, the CSP gives the picture of the actual repercussions of those deeds. Basically, CSP is defined as in Oikonomou et al. (2017) in this thesis.

When it comes to empirical studies, researchers mainly examine the drivers of a better or worse CSP. In their extensive literature review, Aguinis and Glavas (2012) examine the various determinants of CSP. They group them in three main levels: institutional, organizational and individual. At the institutional one, stakeholder pressure is positively related to a good CSP (even more so if said stakeholders are more powerful, legitimated or hastened) in studies included in their literature review. However, the presence of activist shareholders does not lead to converging results. The existence of similar firms (in terms of size, geographical location and operative sectors) oriented toward a better CSP is associated with a better CSP for a firm. The participation in trade or other organizations pressuring for a better CSP is linked to a higher level of social responsibility by a firm. The accent by the media on CSP has a similar effect. Responsible costumers’ behaviours enhance firms’ CSP awareness. A better CSP is also associated with local community involvement in issues concerning a firm. The explicit management of diverse stakeholders’ influences is also linked to a more positive CSP. As for regulations, a focus on compliance and overall population expectations are associated with a better CSP, while certifications (ISO norms for instance) and standards reduce the substantive CSR efforts of firms. Being added or removed (those latter firms try obviously to signal that their removal from the index is not justified) from a sustainability index is associated with an improved CSP. The effect is similar for firms that are environmentally rated by KLD6 or others. National or supranational contexts in terms of

6 The KLD database is the most widely used data source in CSR related studies. In their yearly assessment, KLD review the CSP of about 3000 firms. They identify strengths and concerns on a wide variety of CSR related items. Those strengths and concerns are grouped under seven categories: community, corporate governance, diversity, employee relations, environment, human rights and products. Strengths represent positive actions like using alternative fuels whereas concerns correspond to problems like emitting polluting substances. In the end, for a given strength or concern, KLD assign the value of one if the element is observable for the firm.

11

CSP, type of legal environment or corporate governance practices are also related to CSP. For instance, Lenssen et al. (2007) underline the negative effect of national culture, especially of power distance and masculinity.

As for the organizational level7, Aguinis and Glavas (2012) first identify firms’ motivations to look for a better CSP: the competitiveness of the sector in which operate a firm8, the need for legitimacy, the inclination toward stewardship, justice and responsibility, and the existence of explicit possible gains. Understandably, if a firm aligns its mission and value on CSR, its CSP is higher. Shareholding by executives is associated with a better CSP (Johnson and Greening, 1999). Funds with CSP targets are as well. The decision of businesses’ internalization has an unclear effect. The level of CSP is associated to the type of products (or services) in a firm’s portfolio and their manufacturing means. A higher investment in pollution mitigation processes and machinery is related to a better level of CSP. The importance and influence of the public affairs unit among a firm are also associated with a positive relation to CSP. CEO pay structure has an impact on CSP, long-term (short-term) schemes being positively (negatively) related to CSP (Deckop et al., 2006). The existence of an environmental management system (EMS) also seems to enhance CSP. Firms’ leverage (as debt to equity) is negatively related to firm philanthropic contributions (Adams and Hardwick, 1998). How firms manage (whether they are reactive, defensive, accommodative or proactive9) environmental issues also has an impact on its environmental performance. This effect is variable. Organizations accepting outside technical support are better social performers. Heritage and customs (Galbreath, 2010) of a firm is also linked to CSP. Lastly, Campbell (2007) theorizes that firms with bad financial health and evolving in a negative or

7 The elements related to the board of directors and institutional investors will be addressed in more detail below.

8 The best-case scenario is a middle ground level of competition. This can be explained by the necessity or the possibility of differentiation. A crowed industry will lead to a more vigorous competition in which every niche (including CSP consciousness) is occupied by a rival. Conversely, not enough competitors will reduce incentives to do better in terms of CSP (Campbell, 2007).

9 In short: reactive firms do not engage in any form of environmental management, defensive firms mainly engage in this type of management to insure its compliance, accommodative has formal and involving environmental management, and proactive firms go beyond environmental management as most of the firm is participating willingly to some extent to the environmental target of the firm (see table 1 of Henriques and Sadorsky (1999) for a detailed description).

12

pessimistic economic environment should be less likely to act in a socially responsible manner as they have less money to do so.

There are also some interesting results at individual level. The involvement of supervisors and executives is associated with a higher level of CSP. In house CSR champions help with CSP. Individual with formal CSR training, executives with a sense of CSR and participation by employees in CSR-specific events are all related to a better social performance. CEOs’ and employees’ values as well as the agreement upon such values are also important. Individuals with CSR concerns are associated with a better CSP. Social traditionalists are associated to a lesser CSP (Mudrack, 2007). Last, more intellectually stimulated and community embedded CEOs are as well associated with a better CSP.

In conclusion, various factors influence a firm’s CSP. They are systemic, corporate and individual. For instance, the governance of a firm is an important part of its organizational structure. Consequently, CSP’s researchers have a significant interest in this matter. In the remainder of this literature review, I give an insight on the role in CSP of two groups of governance actors: independent directors and institutional investors.

2.2 Board of Directors and CSP

Fundamentally, according to White (2006), the board has three main purposes: (1) advising the executives on central matters (missions and values for instance), (2) overseeing the firm performance and policies, and (3) managing its own destiny. Consequently, it looks like that executives and boards can complement each other to some extent. Strategic decision-making is one of those tasks devoted in part to both bodies.10 Nevertheless, researchers using different theories come up with diverse ways of interpreting this separation of powers and the possible role of boards.

Foremost, the agency theory “views the modern corporation as a nexus of contracts between principals and agents and has made valuable insights into many aspects of the executive-shareholder conflict and, as so, into the role of boards” (Ricart et al., 2005:25). In its

10 For instance, Galbreath (2010) points out that any type of formal strategic planning is positively related to CSP. He broadly defines “formal strategic planning effort [as] a set of explicit processes firms use to make possible adaptation to both market and non-market environments” (513).

13

monitoring role, the board must make sure that the firm is not wasting shareholders’ wealth in its operations. Agency theory helps to explain this function. As there is a separation of the ownership and the control in modern firms, there is a need for a monitoring body to ensure the effective use of money inside the firm. In a social performance context, the agency theory explains why, as a group, the directors could seek to avoid CSP related investments that are not per se value creating for the shareholders. Inversely, directors could probably emphasize the use of resources to ensure a higher level of CSP in order to sidestep an important loss of firm value resulting from wrongdoings. Nevertheless, some minor CSP issues are not worth their attention. In their two-dimensional agency-theory-inspired typology, Weitzner and Peridis (2011) identify the nature of the situations requiring the consideration of directors. In terms of corporate project, when the potential gains are high but the CSP risk is also high, the board must oversee the project’s orientations in order to ensure that the executives (whom receive compensation mainly based on profitability) do not overestimate the potential benefits at the expense of the actual risks. When the projected payoff is low and the CSP risk is high, the project should not be conducted. However, if it is nevertheless initiated, an active overseeing by the board is required. When the prospect of benefits is high, and the societal risk is low, the attention of directors is not needed as most of the stakeholders (including shareholders and executives) would be pleased with the possible outcomes. The final state of low benefits and low CSP risk leads to a project with safe predictable outcomes. This project could be safely conducted, but it is relatively unappealing for the executives.

The resource dependence theory proposes that board members have access to information, supplies, relations, etc. important for the firm. The boards’ function of resource providers includes four different types of benefits for the firm: (1) advice and counsel, (2) legitimacy, (3) communication channels between the firm and other organizations, and (4) support for important outside elements—material or immaterial (Hillman and Dalziel, 2003). As one can interpret, the resource-based theory proposes that directors are themselves an asset the firm uses to supply other tools.

The four corporate benefits brought to the firm by directors above help uncover how the resource-based theory shapes the debate around CSP issues and entitles the directors to promote their interests. I derive the four following points from the discussion in Hillman and

14

Dalziel (2003). First, when it comes to the advisory role of the board, the executives (most likely the CEO) will generally ask the directors for their input on strategic matters. Directors who are knowledgeable in particular fields will impact more strongly the strategy related to those realms. By inflecting the strategy toward what they believe better suits the needs of the firm while not impairing their reputation, they will naturally, in the end, influence the CSP. Second, as firms turn to some directors to enhance their legitimacy, they are essentially hoping that the reputation of individuals will help the firm’s image in general. They must make sure that those directors feel heard and welcomed unless they might just quit. This situation is also true for CSP. Even if a given nomination were solely for legitimacy purposes, a board that would fail to listen to a member with a high level of CSP credibility would risk the resignation of that director. Third, being the link between the firm and its environment, independent directors are more likely to be aware of problems concerning the firm as expressed by stakeholders (employees, government, suppliers, customers, etc.). Directors will naturally have their voice heard when CSP issues related to their network come to the board. Doing so insures that a firm keeps important bidirectional communication channels open. Fourth, Hillman and Dalziel (2003) state that firms will hire directors linked to the specific element11 needed for the conduct of their business. Consequently, such directors affect the performance of a firm simply by actively helping firms acquire such elements.

Nonetheless, Hillman and Dalziel (2003) posit that it is necessary to involve more than one theory to encompass the whole role of the board of directors.12 Following prior literature, they identify two primary functions of the board: (1) monitoring and (2) providing resources to the firm. They explain the former with the agency theory and they get insights from the resource-based theory for the later. Similarly, only the agency theory and the resource dependence theory authorize a strategic role for the board according to Ricart et al. (2005).

For its part, Moir (2001) uncovers three (main) theoretical basis used by researchers to justify CSR actions in the corporate world: the stakeholders approach (Freeman, 1983; Freeman, 1988; Kassinis and Vafeas, 2002), the social contract (Gray et al., 1996), and the legitimacy

11 “Element” here has a broad definition that encompasses a wide array of inputs a firm needs to operate. It ranges from the obvious physical goods to the more ubiquitous governmental laws (Hillman and Dalziel, 2003; Bear et al., 2010).

15

theory (Suchman, 1995). The stakeholders approach states that a firm must please more than its shareholders to ensure its success. In the social contract theory, the firms are given a right to operate under some (written and unwritten) rules and they must behave according to such rules (including CSR ones) in order to maintain this privilege. The obligation to be useful and desirable as a firm is how the legitimacy theory justifies the existence of CSR actions. Other theories are also present in the literature.

The risk management theory (Godfrey et al., 2009) propose that behaving in a socially acceptable manner for a firm is essentially a way to reduce the possibility of harmful events. For its part, the internationalization theory suggests that firms will expand abroad in order to lower its cost, and to control more of its production process. Increasing CSP usually requires important investment. In developed countries, minimally following basic legislation is usually costly, left alone many other stakeholders’ demands. Consequently, internationalizing theorists posit that firms expand their operations abroad to reduce, among other things, their compliance and CSP cost (Strike et al., 2006). Firms will simply choose a “pollution heaven” where they can operate at the lowest possible cost as theorized by Berrone and Gomez-Mejia (2009).

Other researchers do not use theories per se to justify CSR actions by firms; they rather use working hypotheses. The management quality hypothesis (Godfrey et al., 2009) states that the executives utilize their treasured time to address CSR issues to signal to the market that they have the entire control over all the matters concerning their firm. CSR actions might just as well be window-dressing (Connors et al., 2017); be increasing the value of a firm or simply be the will of the executives (Cai et al., 2012). Finally, firms with slack resources could be the only ones able to act responsibly (CSR-wise) as they have free cashflows and supplies to use for this purpose (Johnson and Greening, 1999; Strike et al., 2006; El Ghoul et al., 2011).13

To understand the possible role of independent board members in CSP, it is necessary to consider two relations: directors – shareholders and directors – executives. First, the fiduciary

13 Another theory that might be of some interest is used by Bruynseels and Cardinaels (2013) in their paper about boards’ audit committee. They use the managerial hegemony theory to describe the way CEOs select directors having similar views on corporate decisions to facilitate their manoeuvring. In the context of CSP, CEO could do the same to limit the effect of having directors with opposing views on the board.

16

duty of the directors is their prime responsibility when it comes to shareholders. While this duty used to mainly encompass financial obligations, SOX and court rulings have inflected a change in this paradigm imposing more legal obligations to independent directors (Bone, 2009). Nowadays, new obligations lead to a new emphasis on long-term financial and non-financial performance parameters (including CSP). Ingley (2008:34) goes further, while acknowledging that boards can only care about financial issues, he states that “the real implication of CSR for corporate decision-making is that it is a governance issue, which means it belongs on the Board’s agenda.” In the end, this means that important CSP related matters should be addressed at board level. However, even if they are involved in this process, not all the independent directors have the tools and the background needed to understand CSP issues thoughtfully. In a survey (Bart, 2007), directors ask for access to CSP specialists that might help them achieve better strategic decisions. This supports the idea that independent board members believe that CSP related decisions are important for boards and, probably mainly, that they are under-equipped to make them. They are also pressured to do so by (activist) shareholders (Rodrigue et al., 2013).

Nevertheless, executives tend to refer to board members in critical CSP situations when damages already occurred (Weitzner and Peridis, 2011). This is a less-than-optimal situation that leaves the directors out of the decision-making process. Therefore, they become less able to monitor executives and advise them (when CSP issues arise during the strategic planning process for instance). Obliviously, some circumstances are better suited for their interventions as described above. Rose (2007) observes that while experienced corporate directors recognize the ethical implications of their actions, they purely act a certain way in order to reduce their legal risk in many cases. Carroll (1999) acknowledges this reality by inserting the legal responsibility at the second level of its pyramid-shaped model of CSR.

An indication that board members understand their role in shaping the CSP of firms, a fair proportion of boards has implemented formal structures dedicated to these matters. Moreover, Ricart et al. (2005) find that socially performing firms have hands-on boards. In these firms, directors tend to explicitly select the way CSP issues will be addressed at the board. While specifying that more complex structures are related to a better CSP, Ricart et

17

al. (2005)14 identify five different strategies of boards addressing CSP issues: (1) the presence of a dedicated committee of independent directors15, (2) the creation of a joint committee of directors and executives consecrated to CSR, (3) the addition of CSR to the mandate of an existing committee, (4) the selection of a board member as the person in charge of CSR topics and (5) the use of board meetings to discuss CSR matters.

In sum, the corporate board has a role to play in the decision-making process mainly by helping the executives (by advising and monitoring them) assess CSR risks of business operations. In that sense, one of the board’s duties is to act as an arbitrator between shareholders, executives and other stakeholders. Moreover, the previous paragraphs show that this is a role recognized by directors.

2.2.1 Board Level Variables

While there are theories outlining probable directors’ CSR behaviours in the literature, there is also a good amount of empirical work. In this section, I examine these research studies. Five determinants of CSP are tested at board level: board size, CEO-chairman duality, CSR committees, audit committees and board independence.

Board Size

For board size, “a resource dependence view suggests that larger boards enhance firm performance by ensuring a greater ability for firms to form links to their environment to secure critical resources” (Kassinis and Vafeas, 2002:401). Greater resources provide more financial freedom thus enabling CSR-oriented actions. More directors also deliver more expertise on CSR related issues. Large boards can also accommodate more stakeholders’ delegates and their concerns along the way (Hafsi and Turgut, 2013). However, a larger board might be plagued with some inertia, just as a large boat needs more time and space to make a turn. They will need more time to conduct regular duties, leaving them with fewer opportunities to discuss about CSP issues. A large board also lacks the needed cohesion to conduct difficult, but necessary, CSR actions (Kassinis and Vafeas, 2002). Accordingly, when tested, the relation between CSP and board size does not lead to consistent results.

14 In the paper, they compare 18 better performing firms to 800 average firms to uncover the particularities of their governance CSR’s governance practices.

18

Sometimes the association is positive (Kassinis and Vafeas, 2002; Walls et al., 2012; Jain and Jamali, 2016), negative(Jain and Jamali, 2016) or not existent (Hafsi and Turgut, 2013; Jain and Jamali, 2016).

CEO-Chairman Duality

The CEO-chairman roles’ separation “has been promoted as a distribution of power which enhances the board’s ability to monitor managers’ decisions” (Hafsi and Turgut, 2013:466). This autonomy of the board eases reason-induced, rather than pressure-led, CSP decisions. On the other hand, a CEO occupying both positions might send a message of strong leadership for the firm enabling a simpler and quicker decision-making process (Mallin and Michelon, 2011). The separation widens the information asymmetry gap between the board and the executives. In the literature, researchers find either a positive (Bear et al., 2010), a negative association (Mallin and Michelon, 2011) or no link (Hafsi and Turgut, 2013) between the separation (of the role of chairman of the board and CEO) to CSP. That said, this latter result (no relationship) is the most prevalent (Jain and Jamali, 2016).

Directors’ Independence

Also related to the board structure is the independence of board members. Mallin and Michelon (2011:123) suggest that “by being more dedicated to stakeholders’ expectations, independent directors will increase their own prestige and role in society and thus they will be more likely to encourage the company to undertake CSR activities.” In the same vein, independent directors bring new knowledge of the community and the environment of the firm. This information can help make better CSP decisions (Haniffa and Cooke, 2005). Also, independent directors must protect their reputation making them more reluctant to legal complications. The proportion (or number) of independent directors is the main variable of interest of several reviewed studies (Johnson and Greening, 1999; Harjoto and Jo, 2011; Mallin and Michelon, 2011; Walls et al., 2012; Hafsi and Turgut, 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Rao and Tilt, 2016; Shaukat et al., 2016). Having more independent directors is mainly related to a better CSP even though some researchers find no association or even a negative

19

one (Jain and Jamali, 2016; Crifo et al., 2018).16 Sometimes, the independence of directors is associated to CSP in general, other times it is only related to specific dimensions and, in some circumstances, the authors reveal no relation at all between CSP and board member independence. In the CSR disclosure literature, surprisingly, the presence of non-independent directors positively influences information availability in the Malaysian setting (Haniffa and Cooke, 2005). This is in line with the legitimacy theory which is often associated with environmental disclosure, nonetheless. However, Rupley et al. (2012) observe that the presence of independent directors has the exact same positive effect on CSR disclosure.

On a parallel topic, Kock et al. (2012) define directors’ independence differently. They split directors in two groups: pro-stakeholder ones and industrially trained ones. They suppose that the first group has different goals when compared to executives of the firm. Thus, those more authentically independent directors are “less likely to tolerate environmental irresponsibility because their interests are more closely aligned with the interests of the community at large” (Kassinis and Vafeas, 2002:401). Conversely, “the interests of insider directors and outside directors that hold executive positions in other industrial organizations, because of their involvement in industrial activities, will be closer to managers’ interests” (Kock et al., 2012:503). In their paper with internal and external governance variables included17, Kock et al. (2012) determine that having stakeholders-oriented directors is related to a better CSP.

CSR-Targeted Structures and Processes

Committees are important for boards. In fact, a fair proportion of boards’ decisions are issued at this level (Kesner, 1988). A committee dedicated to CSR matters at board level, “can be interpreted as a signal that the firm sends to stakeholders in order to show its commitment and involvement in CSR” (Mallin and Michelon, 2011:125). The creation of such a committee by the directors is also a manner to explicitly indicates to the board itself that CSR

16 Crifo et al. (2018) argue that their findings tend to contradict both the agency theory and the stakeholders’ approach. As stated above, both theories suppose that independent directors should be associated with a better CSP.

17 Kock et al. (2012) study: anti-takeover provisions (Gompers et al., 2003), the presence of limited-liability clauses in firm’s statutes (limited liability clauses, indemnification clauses, indemnification contracts), directors not from an industrial sector as pro-stakeholders, and equity-based managerial incentives (both as part of revenue and overall wealth).