Describing collective creation of knowledge about competitive environment. The case of a business intelligence service

Cécile Belmondo

Cahier n°323

Juin 2003

Cécile BELMONDO Laboratoire DMSP Université Paris IX Dauphine Place du Maréchal de Lattre de Tassigny

75016 Paris

Résumé

Les processus collectifs de création de connaissances restent peu explorés. Cependant, une bonne gestion des connaissances, si elle vise à soutenir le développement et le partage des connaissances dans l’organisation plutôt que simplement aider à leu mémorisation, ne peut faire l’impasse sur l’étude de tels processus. Dans ce cahier de recherche, nous présentons une analyse comparative de deux processus de création de connaissances au sein d’une cellule de veille concurrentielle. Nous avons étudié cette cellule de veille durant 16 mois. Le recueil de données a été effectué au moyen d’une observation participante. Le codage émergent des interactions au sein et à l’extérieur du groupe constitue la base de l’analyse. Les créations de connaissances ont été évaluées par le différentiel entre connaissances entrantes et sortantes. Nous avons étudié les trajectoires des catégories émergentes et les avons représentées graphiquement, ce qui nous a permis de distinguer les phases des processus. L’analyse mène à un modèle en cinq phases qui peuvent être décrites au moyen de six variables : interactions au sein du groupes, interactions du groupe avec d’autres groupes de l’organisation, demandes de connaissances depuis ou au groupe, réceptions de documents, diffusion de document et contexte. Cinq phases ont été mises en évidence dans les processus : attentisme, fragmentation, intégration, rationalisation et exploi-tation. Elles représentent des « briques » du modèle avec lesquelles décrire les processus collec-tifs de création de connaissances.

Mots clefs :

Environnement concurrentiel, connaissance, processus, étude de cas, création de connaissance

Abstract

Collective processes of organizational knowledge creation remain poorly explored. Yet efficient knowledge management has to focus on those processes as far as it aims at dealing with sustain-ing knowledge development and sharsustain-ing rather than solely sustainsustain-ing its memorization. In this paper, we present a comparative analysis of two processes of knowledge creation within a busi-ness intelligence service. We studied this busibusi-ness intelligence service during 16 months. Data collection was done through a participant observation methodology based on a half time partici-pation in the business intelligence service. Emergent coding of interpersonal interactions within and outside the group is the basis for data analysis. Knowledge creation was evaluated by the difference between received and diffused knowledge. We studied the trajectories of the emerging codes and graphically represented them. Two graphical representations of the processes were used to bracket different phases we then characterized.

The analysis led to a five stages model that can be described with six variables: interactions within the group, interactions outside the group, requests of information to or from the group, received documents, diffused documents and organizational / environmental context. We high-lighted five different phases intervening in the processes: attentism, fragmentation, integration, rationalization and exploitation. They represent the basic “bricks” of the model. Real processes can be described by the arrangement of those different bricks.

Key-words:

Introduction

Starting from a rather narrow conception of knowledge within organizations, as stocks to be up-dated and memorized, knowledge management research has been enlarging its focus to more complex issues such as knowledge preservation/updating/transfer through and between organiza-tional actors (Cook and Brown, 1999). Today, knowledge management aims at sustaining knowledge transformation and creation (Hatchuel, Le Masson and Weil, 2002). This evolution leads to a central issue: how is knowledge created within organizations? If managing knowledge means sustaining its creation rather than its memorization, then indeed knowledge management research has to develop a thorough comprehension of what are those processes it aims at sustain-ing.

Also, although the effects of managers’ perceptions and possessed knowledge have largely been analysed in previous studies, little has been done on how they actually create knowledge. There-fore, our paper aims tries to provide new insights about knowledge creation processes that will be useful both to knowledge management researchers and to researchers interested in the forma-tion of organizaforma-tional strategies.

Our research consists of a comparative analysis of two collective processes of knowledge crea-tion. Both processes lead to new knowledge about an organization’s competitive environment and take place within a competitive intelligence service. Competitive intelligence services are great fields for observing knowledge creation because of their need to finally transfer their knowledge to decision makers.

We study both processes through inner and outer group’s interpersonal interactions. Interactions enable to bridge the view of knowledge as stocks (within individual and organizational memo-ries) and of knowledge as flows (between individuals or organizational groups) (Eisenhardt and Santos, 2002).

In the first part of this paper, we briefly describe our methodology for data gathering and we pre-sent the group we observed. Then we give a detailed account of the two processes we analysed. In the second part of the paper, we explain our methodology for processual data analysis. We use the concept of knowledge pertinence to evaluate received and diffused knowledge. The variation between received and diffused knowledge is used to evaluate the knowledge creations that occur during the processes. Finally, in the third part of this paper, we present a model of collective processes of knowledge creation based on the comparison of both processes’ different phases.

1. Case description and accounts of the processes

Data gathering

Our methodology uses three classical methods for analyzing processual data (Langley, 1999). We use a “grounded theory” methodology to design conceptual categories that emerge from the data. The systematic analysis of these categories’ content leads to the identification of phases within their trajectories (“temporal bracketing”). Then the trajectories’ graphical representation leads to the bracketing of global phases for both processes (“visual mapping”).

Primary data gathering was done through a participant observation of 16 months, from January 2000 to April 2001. We observed the group’s activities on a 2.5 days a week basis. We com-pleted the obtained data with a systematic gathering of secondary data at hands. We used a re-search diary to keep a trace of the data and to make easier the a posteriori rebuilding of the proc-esses. Gathered data was chronologically arranged in detailed accounts of the cases, that were validated by the group’s members.

Description of the research field

The research field we selected is a competitive intelligence service in the “Direction des Clients Résidentiels et Professionnels”1 (Residential Customers and SMEs Direction, DCRP) of the

French incumbent company of telecommunications: France Telecom. DCRP is in charge of fixed telephony for residential and SME markets. It is strongly marketing oriented. Its competitive en-vironment can be said to be turbulent and complex from January 2000 to April 2001. By that time, the fixed telephony market deregulation is recent: it officially started in January 1998 but the first offers to residential customers don’t appear before the beginning of 1999. Regulatory evolutions - especially carrier preselection and local loop unbundling2 - make year 2000 a very important year in the development of competition.

The role of the competitive intelligence service is to provide decision makers with all the knowl-edge it considers as useful for understanding the competitive environment’s evolution. It also supposed to quickly give pertinent answers to decision makers’ questions. It thus plays an impor-tant part in the DCRP decision-making processes.

The group was created in July 1998. It reached its definitive size six months before our entering of the research field. By that time, it is composed of three persons: Claire (the supervisor), Chris-tine and Nicole. Its small size made easier the exhaustive gathering of interpersonal interactions within and outside the group. Claire, Christine and Nicole all have big company seniority but none of them ever worked in a competitive intelligence service. I worked with them as a trainee from January 2000.

The group’s organization and interests are built upon themes, of various interest and complexity.

The group uses the term “theme” to nominate a consistent set of knowledge. We retained

this term to delimitate the two cases we study so that we stay close to the group’s organization. We draw the reader’s attention to the fact that the group has not been created in order to create knowledge about specific and well defined themes and that its objective is not to create consis-tent sets of knowledge about such themes. Rather its role is to continually provide decision mak-ers knowledge about themes that either the group or the decision makmak-ers consider as important at a given moment.

From January 2000 to April 2001, the group worked on 16 themes. The themes treatment is col-lective since the group’s members debated about them during weekly “team meetings” and dur-ing other planned or informal meetdur-ings. Within the most important themes, we can distdur-inguish those dealing with competitors’ marketing mixes from “transverse” themes dealing with major regulatory evolutions: number portability, wireless local loop, local loop unbundling and carrier preselection2.

We chose to study the two latter themes because we gained very close access to the work the group did on those themes. Furthermore, the process concerning the theme of local loop unbun-dling led to a linear and logical succession of phases: after a period of “attentism”, the group’s members individually work on sub-parts of the theme. The knowledge created on those sub-parts is then integrated in a global knowledge of the theme. Methods used for this knowledge creation are then rationalised. Finally, both created knowledge and methods are used as a basis to exploit new perceived competitive moves. The comparison of both processes allows us to make this lin-ear model more complex and to examine each type of phase’s utility.

1 Units and people’s names have been changed.

2 In France, the deregulation of the telecommunications market followed two paths. The first one is called “interconnexion”: when a customer

uses a long distance carrier other than the incumbent, the latter carries his calls to a point of interconnexion between its network and the former’s network. To use a long distance carrier on a “call by call” basis, customers have to type an access code before the phone number they want to type. Carrier’s preselection is the association of a customer and an access code, so that this customer no longer has to type the code to use the carrier he selected for his national and international calls. This system prevents competitors from losing calls volume because of their customers forgetting to type their access code.

Local loop unbundling is the second path used to deregulate the telecommunications market. A local loop operator lends France Telecom the

local loop that links a customer to the nearest switch. Thus France Telecom loses all its former commercial contacts with this customer. The com-petitor bills all the customer’s calls and his subscription. Unbundling is costly but is a good way for a comcom-petitor to propose global offers to its customers.

Cases description

We observed both processes of knowledge creation from our enrolment in the group until its dis-appearance following a reorganization of DCRP. The group collectively worked on both themes all along the observation period. In the next paragraphs, we describe the group’s activities con-cerning both themes. Each description starts with a brief memo of the context and then chrono-logically presents the successive interactions and knowledge creations that took place during the themes’ treatment.

1.1.1 Knowledge creation about local loop unbundling

At the beginning of 2000, the date when the local loop unbundling act will be effective is not yet certainly known but it is expected for the end of the first semester. The second semester starts with two stages of experimental tests of unbundling. The first “real” offers of local loop unbun-dling appear during the first trimester of year 2001.

At the beginning of the observation period, the theme is studied as a part of a larger theme: com-petitors’ forthcoming positioning on the local loop market3. The group tries to anticipate which

competitors are most likely to enter this market and what their offers will be. By that time, the group’s searching is quite general. In January 2000, Christine, Claire and Nicole systematically explore the company’s databases. On 01/24/2000, Christine said, “the local loop unbundling re-cord is nearly complete”. The group is satisfied with its searches: it can integrate the theme to analyses dealing with other themes, such as strategic analyses of important competitors (diffu-sion of analysis on 03/23, 04/06 and 04/25/2000). Knowledge about local loop unbundling is rather general and theoretical: entry barriers, size of the necessary investments, identification of substitute technologies…

Because of this satisfaction, the group’s interest for unbundling lowers from February to April 2000: the group doesn’t quote the theme anymore during its weekly meetings nor in its diffu-sions. Interest for the theme rises back in May 2000: other services the group has relationships with work on the theme. Moreover, upper levels’ meetings’ records mention the theme more of-ten. When Claire’s immediate supervisor starts working on local loop unbundling, Claire says, “we should get back to the theme” (05/15/2000). Thus the group organizes its work: Christine gets officially in charge of the theme and Nicole is in charge for building a list of potentially in-teresting indicators for the theme’s treatment.

Quite quickly, it appears that practically no data dealing with French unbundling is available. The group’s members thus have to imagine what the offers will be using data about unbundling in other countries. In June, the group asks other organizational units for benchmarks about abroad local loop unbundling. The answers are not useful. The group also focuses on the techni-cal details of the theme in order to evaluate the strength of technitechni-cal constraints. Claire and Christine work with two “partners” expert in telecommunication techniques and regulation. But those technical issues are not so simple and they have difficulties assessing their consequences on forthcoming offers: “he [one of the partner] was too fast on the phone. I couldn’t understand everything” (Claire, 06/19/2000). Even after three working meetings, Claire won’t be sure of her understanding of the technical constraints. She will eventually get more comfortable after her visiting of the technical installations of local loop unbundling: after one of those visits, she as-serts, “I could physically see all we usually speak about” (06/26/2000).

Finally, all those searches lead to little new knowledge. It is only from September 2000 that the group will start diffusing knowledge that it created on its own. Yet this knowledge will still be “theoretical”.

On 09/26/2000, Claire sends the group’s members a memo of the directives given by DCRP’s director at the end of a very important presentation the group made to him on 09/19/2000. The theme is said to have priority: “we have to get a vision of the competitors’ speed and scope for

their roll out of local loop unbundling. Our goal is to know when customers get their first ad-verts for unbundled offers”. Answers to these directives have to be presented during another meeting on 11/14/2000. Directives are wide and need a consequent set of data to be answered. Yet Claire notices on 10/02/2000 “we know little about local loop unbundling”. Therefore, the group goes back on looking for data about unbundling in other countries. A partner in the USA gives it a memo that is “complete but quite technical” (11/07/2000). It will be used for the meet-ing’s preparation. As far as unbundling in France is concerned, the group seeks help from sales agencies chosen within its members’ personal relationships and according to the sales agencies’ exposure to competition on the local loop (with other technologies such as optical fiber or wire-less loops). Claire makes clear their objectives: “we need to get the sales aspect, particularly competitors’ direct marketing strategy. That’s why we ask the sales agencies” (10/02/2000). The group’s relationships with sales agencies will reveal fruitful. Thanks to them, the group gets a qualitative evaluation of some competitors’ willingness to enter the unbundling market.

The very creation of a consequent and global knowledge about the theme takes place during two brainstorming meetings on 10/24 and 11/09/2000. The first meeting’s goal is to build a typology of the competitors regarding some key indicators. During the two following weeks, the group gathers and categorizes its knowledge along these indicators. The second meeting’s goal is to sharpen the typology so the group can work on no more than one competitor per type. By the end of those two meetings, data gathering is done: “now, we must stop looking for data and start thinking” (Claire, 11/09/2000). So does the group during the following week.

On 11/14/2000, during the meeting with DCRP’s director, the group’s members give an organ-ized account of all the knowledge they created about local loop unbundling. The typology they created during the two brainstorming meetings is used as a frame that helps making sense of the knowledge created about unbundling in foreign countries and of the knowledge created thanks to the group’s interactions with sales agencies. Anticipations of each type of competitor’s offers are explained by a comparison between local loop unbundling and other local loop technologies. During the meeting, the group’s members are confident with the knowledge they diffuse.

Reactions to the meeting are positive: the group’s internal customers think it has created very interesting, pertinent and exhaustive knowledge. Consequently, during the two following months, the group stops creating new knowledge and works at capitalizing on its old knowledge and at rationalising its methods so that it will be able to faster integrate any new competitive move relating after local loop unbundling has become effective. The rationalisation is made through a reduction of the number of competitors taken into account so that the group can focus on no more than one competitor per type. Competitors are selected during two “methodology meetings” on 12/11 and 12/21/2000.

January 1st, 2001 is the day when unbundling is “officially” open. From that day, the group has no more to anticipate what competitors’ moves will be but to check whether its anticipations were wrong or not. To work on this new issue, the group keeps in touch with some of the sales agencies it had had relationships with. As an example, on 01/15/2001, Christine says she is go-ing to “give a qualitative phone call to feel which competitors are gettgo-ing ‘active on the field’”. These interactions, and some personal searches by its members, allow the group to more regu-larly diffuse knowledge about the rollout of unbundled local loops. The group also shares its knowledge with different partners, mainly with a workgroup working on DCRP’s strategic plan-ning.

1.1.2 Knowledge creation about carrier preselection

The second process we studied allowed the group to create new knowledge about the theme of “carrier preselection” (CPS). This process revealed itself to be more cyclical than the first one. We successively observed a phase of “incomplete” integration, then a phase of attentism, then again a phase of “incomplete” integration and of attentism and finally a phase of “complete” in-tegration and of attentism. In next paragraphs, we briefly explain what is CPS and then give an account of the process.

CPS for long distance calls is effective from January 17th, 2000. Its extension to calls to mobiles4

is expected in the forthcoming months (it will finally happen in November 2000). At the begin-ning of 2000, competitors on the long distance market make little advertising for CPS. The first offers appear at the beginning of March 2000: 9 Telecom bundles a lower tariff with preselec-tion. The two main competitors’ reactions (Cegetel and Tele2) are quick but not particularly competitive. Overall, few competitors will make specific offers for CPS during year 2000. Most of them will promote it in their “classical” advertising campaigns, through punctual offers or by bundling CPS with Internet offers. Nevertheless, by the end of 2000, more than one million resi-dential customers have subscribed CPS (about 25% of customers using long distance carriers other than the incumbent).

From January 2000 until 02/21/2000, the competitive intelligence service systematically quotes or discusses issues related to CPS during its weekly meeting. It gets information about CPS from specialised or generalist newspapers and from other organizational groups. In January, the group work hard on different sub-themes related to CPS: carrier preselection for calls to mobiles (by that time, perceived as coming soon), CPS’ profitability and interest for competitors. Other sub-themes are debated, particularly during the weekly meeting on 01/17/2000: CPS’ theoretical in-fluence on call volumes, estimation of the amount of CPS subscribers, PBX owners’ benefits to engage in CPS5, customers’ use of the access code “8” (France Telecom’s access code)6, the

re-moval of the “Zone Locale de Tri”7 (Local Exchange Area)…

All along, the group wonders about the different sources of information it can use for the theme. Their accessibility is not ensured and the group has doubt about how to get in touch with them. The group isn’t sure either of how it should organise itself. The collective debates about different sub themes raise many questions and are most often followed by a method or a list of actions to undertake. Yet those actions are not assigned to anyone in particular. Claire is conscious of this “disorganization” and of the large number of sub-themes the group works on. On 02/21/2000, she tries to organize the group a little better: “we have plenty of things to do: we need to create a sort of CPS operating report for its roll-out and its consequences […] We have two main issues to work on: CPS roll-out and CPS offers. Should we give the first issue to Christine and the sec-ond one to Nicole, or both to one of them with a contingent help from the other?”. Finally, Nicole is assigned to work on the theme and most of all to centralise the information on CPS the group finds.

Nothing important happens during the two following months (March and April 2000): a few dif-fusions are made that shortly mentions CPS within wider sets of knowledge about competitors’ strategies or in punctual “alerts”. May 2000 is a more active month. The weekly meeting of 05/02/2000 is mostly dedicated to the fact that “our competitors make more and more CPS

4 At the beginning of year 2000, CPS is effective for national and international (long distance) calls, which is by then the only deregulated

mar-ket. On 11/01/2000, another market is deregulated: calls to mobiles. Call by call and CPS are made available and the extension of CPS to calls to mobiles is automatic.

5 PBX are telecommunication routers that centralize a company’s internal and external calls. They can be programmed so that they do Least Cost

Routing: they use a different carrier according to the call destination or time. Thus, carrier preselection, which associates a company with only one carrier for all its calls, is theoretically much less interesting for them.

6 A CPS customer still can use other carriers on a call-by-call basis, by typing their access code. As the incumbent carrier, France Telecom is

chosen by default. “8” is the access code the regulator gave it so that CPS customers still can use France Telecom as a carrier with call by call.

7 Deregulation of the local telecommunication market is supposed to follow the same path than did the deregulation of the calls to mobiles

mar-ket: with an automatic extension of carrier preselection to this type of calls. This extension of CPS is also called “removal of the “Zone Locale de Tri” (Local Exchange Area). The deregulation happened in January 2002.

fers”. Once more, numerous sub-themes are quoted. They related to a shorter time horizon than the ones the group mentioned in February: how a customer can change its CPS carrier, competi-tors’ CPS contracts, advertising campaigns and offers, the theoretical possibility to use a CPS carrier for Internet access… Those sub-themes lead to numerous repartitions of tasks between Nicole and Christine: Christine has to make a “synthesis of the quantitative aspect of CPS” (05/02/2000) and Nicole gets in charge of the “qualitative” part of the theme, such as the study of CPS contracts, offers and advertising campaigns. In that order, she makes profit of her steady relationships with the “Competition Group”, the group’s closest partner. During May 2000, she works with it on a “field” study of CPS selling.

On May 2000, the group makes a first “synthetic” diffusion: an exhaustive inventory of CPS of-fers. An e-mail comments on the table summarizing the ofof-fers. It is a first step toward an analy-sis of competitors’ strategies: “leaders (generalist or focused carriers) try to make their custom-ers loyal to their offcustom-ers so that they can collect the call volumes that they used to lose because of their customers forgetting to compose the right code access. They also try to expand their offers to other types of calls (calls to mobile, regional calls). Other competitors, such as operators with an access code like 16XY8, try as much as possible to get new customers” (05/30/2000).

In June 2000, the group focuses again on the forthcoming preselection for calls to mobiles. It is now expected for September 2000. Claire twice meets the group’s partners that are expert in telecommunication techniques and regulation issues. She debates with them about the foresee-able impact of calls to mobiles preselection upon calls volumes and about some details of this forthcoming regulation. Nicole works on the anticipation of the impact of calls to mobile prese-lection upon preseprese-lection in general.

The theme is not much mentioned during an important meeting with DCRP’s director on 09/19/2000. However, after the meeting, the director asks the group some questions about the theme. The most important question deals with CPS sales organisation: “how do our competitors sell their preselection offers?”. To answer, Claire organizes a survey about the most important distributors that sell CPS. By the beginning of November 2000, Nicole has gathered facts on competitors’ sales methods. She diffuses them on 11/10/2000. Those facts are also quoted during the oral presentation on 11/14/2000. This presentation only contains three slides dealing with CPS. It starts with an explanation of its roll out and an estimate for the end of the year. The treatment of the sales methods issue is very factual, which shows that the group has just started creating knowledge about this specific sub-theme.

At the end of the meeting, the DCRP’s director asks the group to be more precise concerning competitors’ CPS strategies. More precisely, he wants to know if they all moved “from a logic where they try to get customers to a logic where they try to be profitable” (11/14/2000). Nicole makes a first draft to answer the question and sends it to the group’s other members. Claire writes comments on the draft and the whole group works on it during a special meeting on 11/20/2000. The final draft is diffused on 12/07/2000. It is very synthetic. Only a few examples have been kept and the document systematically examines each competitor’s communication and sales strategies on CPS. The first half page of the document is a synthesis by Claire, which as-serts that leader competitors use CPS as a service and that second range competitors use it as a tool for gaining more customers. There are the only ones that make specific offers for CPS. In the document, the group is confident in its knowledge and uses it for making recommendations to decision makers. Competitors’ distribution strategies are used as a mean to explain their global CPS strategies and to articulate the group’s entire knowledge on the theme.

From December 2000 to February 2001, the theme of CPS is getting less and less quoted during weekly meetings. It doesn’t seem to be a priority anymore. As an example, a study of CPS cus-tomers is delayed until the launching of another study on a cable operator “because we cannot handle both of them at the same time” (Claire, 12/11/2000).

2. Data analysis

The two accounts in former paragraphs are extracts from the accounts we wrote to validate the chronological database that we built for both cases and that were used to make the accounts. It is the data contained in those databases that we used for coding.

Field data coding

9Because we adopted an inductive approach for our research, we needed to use coding categories that did not refer to implicit hypothesis on the observed processes. That’s why we used very wide categories – interactions and knowledge – and emergent sub-categories to describe the processes.

2.1.1 Coding knowledge

We define knowledge as beliefs related to a particular situation and that are temporary and sub-jective. Those beliefs are reflexive: they stood up to a critical thinking or acting by their holder. Also, they are a part of a wider set of previous knowledge.

We consider the group’s knowledge to be knowledge shared by its members. We take for collec-tive knowledge any document the group diffused to partners or to internal customers since there has been a collective agreement for its diffusion and, as such, a critical thinking of the group’s members towards it.

Therefore, the unit of analysis is the “document”, received or diffused by the group. We justify our choice of the “document” as a unit of analysis by the importance given by the group to the shape and the content of the documents it diffuses. Variation of knowledge between received and diffused documents during a given time evaluates knowledge creation.

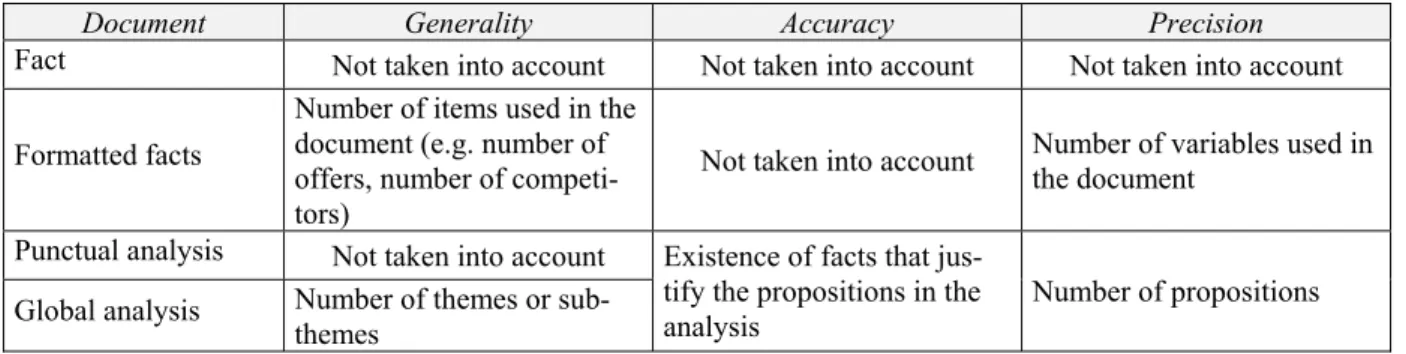

When coding the documents, we found the following emergent categories: facts, formatted facts, punctual analysis and global analysis. Table 1 gives the categories’ definitions. It sometimes happened that knowledge about a given theme was diffused in a document concerning another theme. As an example, competitors’ positioning on the local loop unbundling market has some-times been used in analyses about their global strategy. We coded this event with the term “con-nexion”.

Code Definitions

Fact

Can a “fact” be said to be knowledge? We do make the sensible hypothesis that if the group diffuses some facts then it certainly is because the group evaluated them as strategic and useful to the organisa-tion and therefore diffused facts meet our definiorganisa-tion of knowledge.

Formatted

facts Sets of facts that have implicitly or explicitly been related to each other. As an example, a list of sites of experimentations or a comparison of two tariffs. Punctual

analysis

Analysis about facts or sets of facts. It aims at explaining these facts, to draw attention upon some of their characteristics (e.g. their plausibility) and/or to describe their main consequences.

Global

analysis Analysis of one theme or one sub-theme. They aim at giving a global understanding of the theme.

Table 1: Categories of documents used for emergent coding of knowledge

This typology of documents emerged from the coding of the gathered data. It is similar to the typology proposed by David (2001) of scientific knowledge: formatted facts, first level theory, general theory and axiomatics. This similarity can be explained by the fact that the knowledge created by a competitive intelligence service is founded if not scientifically built.

9 For each case, coding was tested for both inter-rater and test-retest reliability. Test-retest reliability was tested by having the same researcher

recoding the data. Inter-rated reliability was tested by having two researchers blindly code identical data. Agreement scores for reliability are comprised between 82% and 92%.

Our typology is not similar to more classical typologies: tacit versus explicit knowledge (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995); scientific or practical (Scribner, 1986); technologic, commercial or organ-isational (Martinet and Ribault, 1989); intuitive, computational, concrete and principled knowl-edge (Brown, Collins and Duguid, 1989)… This seems to be predictable since we study a very specific type of knowledge: explicit knowledge that is more know-what than know-how, that is more “knowledge about” than “knowledge of acquaintance” (James, 1950).

2.1.2 Evaluating knowledge’s pertinence

Our typology uses a criterion that is at best implicit in some of those typologies: knowledge’s level of generality. This criterion is not sufficient to properly describe the evolution of diffused knowledge, or to evaluate the difference between received and diffused knowledge. The similar-ity of our typology of knowledge with David (2001)’s typology of scientific knowledge led us to take into account the equilibrium between knowledge generality, simplicity and accuracy (Weick, 1979) achieved by the group. We tried to create simple indicators to measure a more adequate criterion for a given level of knowledge generality: knowledge pertinence.

Reix (2000, pp. 24-30) defined three main dimensions that account for a representation’s perti-nence. Completeness (generality) is the taking into account of the whole set of significant events into a given representation. Accuracy is the fact that the representation is bias-free, with bias ris-ing from an internal dysfunction of the organizational information system. Finally, precision is the level of detail at which the representation is made explicit. The more precise a representation is, the less simple it is.

Knowledge received or diffused by a competitive intelligence service is a set of representations about the organisation’s competitive environment. Consequently, it is possible to use those three criteria to evaluate its pertinence. We adapted each criterion to the different types of documents (cf. Table 2). Indeed, not all criteria are adequate to characterize each type of document. As an example, punctual analysis by definition concerns only a little number of events. So complete-ness is not significant. But it is significant for global analysis, which aims at taking into account the whole set of knowledge about a given theme.

Document Generality Accuracy Precision

Fact Not taken into account Not taken into account Not taken into account Formatted facts

Number of items used in the document (e.g. number of offers, number of competi-tors)

Not taken into account Number of variables used in the document Punctual analysis Not taken into account

Global analysis Number of themes or sub-themes

Existence of facts that jus-tify the propositions in the

analysis Number of propositions

Table 2: indicators and measure of pertinence according to the type of knowledge

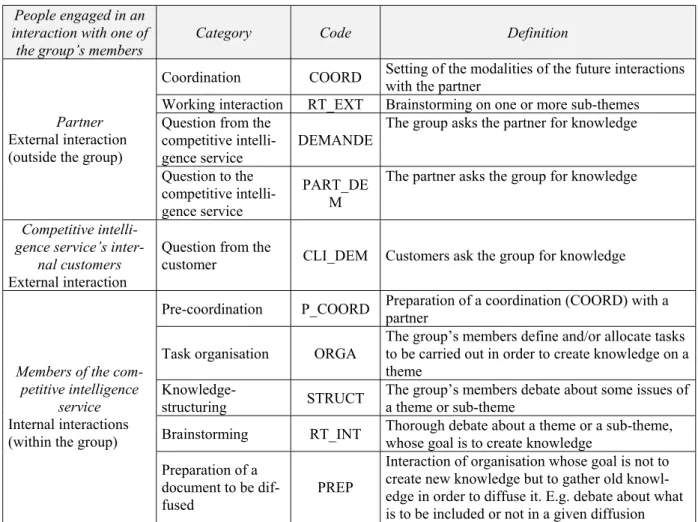

2.1.3 Coding interactions

We coded interpersonal interactions within or outside the group, in order to put into light the successive actions that ended into knowledge creations. Those actions may be collective or indi-vidual; they may be past, present or future. Individual actions were taken into account through the accounts people made of them during any interaction, particularly during the group’s weekly meetings. An emerging coding showed ten categories of interactions (cf. Table 3 next page). Because we used an emergent coding for interactions, the categories’ meaning has been dis-cussed during the comparison of the two processes. Finally, it appeared that the role of knowl-edge-structuring interactions is to help the group to debate about some sub-themes and to gather knowledge and to end in building a shared “problem environment” for the theme. Knowledge-structuring interactions lead to emerging representations and help their progressive convergence.

Newell and Simon (1972) introduced the notion of “problem environment”. They asserted that a problem resolution is a succession of moves within a research environment, this environment being characterised by interpretations of the initial situation, of the goal and of the possible ac-tions that allow to move inside the environment from a situation to another. They call “task envi-ronment” the research environment as it is interpreted by people (i.e. the task environment is a sub-set of the research environment, delimited by the actions people consider as feasible). In our research, the task environment of a theme is defined by the competitors’ initial competitive situa-tions, by the goals they set to themselves (the “stakes” as said by the group’s members), and by the competitive moves they are likely to do.

Brainstorming interactions are a variation of knowledge-structuring interaction that ends in a collective, explicit and transferable representation of the theme. They allow for a consensus be-fore the group’s members prepare the document that will be diffused.

People engaged in an interaction with one of

the group’s members

Category Code Definition

Coordination COORD Setting of the modalities of the future interactions with the partner Working interaction RT_EXT Brainstorming on one or more sub-themes Question from the

competitive

intelli-gence service DEMANDE

The group asks the partner for knowledge

Partner

External interaction (outside the group)

Question to the competitive intelli-gence service

PART_DE M

The partner asks the group for knowledge

Competitive intelli-gence service’s

inter-nal customers

External interaction

Question from the

customer CLI_DEM Customers ask the group for knowledge Pre-coordination P_COORD Preparation of a coordination (COORD) with a partner Task organisation ORGA The group’s members define and/or allocate tasks to be carried out in order to create knowledge on a

theme

Knowledge-structuring STRUCT The group’s members debate about some issues of a theme or sub-theme Brainstorming RT_INT Thorough debate about a theme or a sub-theme, whose goal is to create knowledge

Members of the com-petitive intelligence

service

Internal interactions (within the group)

Preparation of a document to be

dif-fused PREP

Interaction of organisation whose goal is not to create new knowledge but to gather old knowl-edge in order to diffuse it. E.g. debate about what is to be included or not in a given diffusion

Table 3: emerging categories of interactions

Trajectories analysis and graphical representation of the processes

The systematic analysis of the trajectories taken by the categories made possible the reconstitu-tion of two processes of knowledge creareconstitu-tion. Those analyses were done by discussing each cate-gory’s content. Indeed, we used an emerging coding: thus the meaning of each category is not a priori established. It would have been dangerous to build our analysis only on a comparison of the codes’ names.

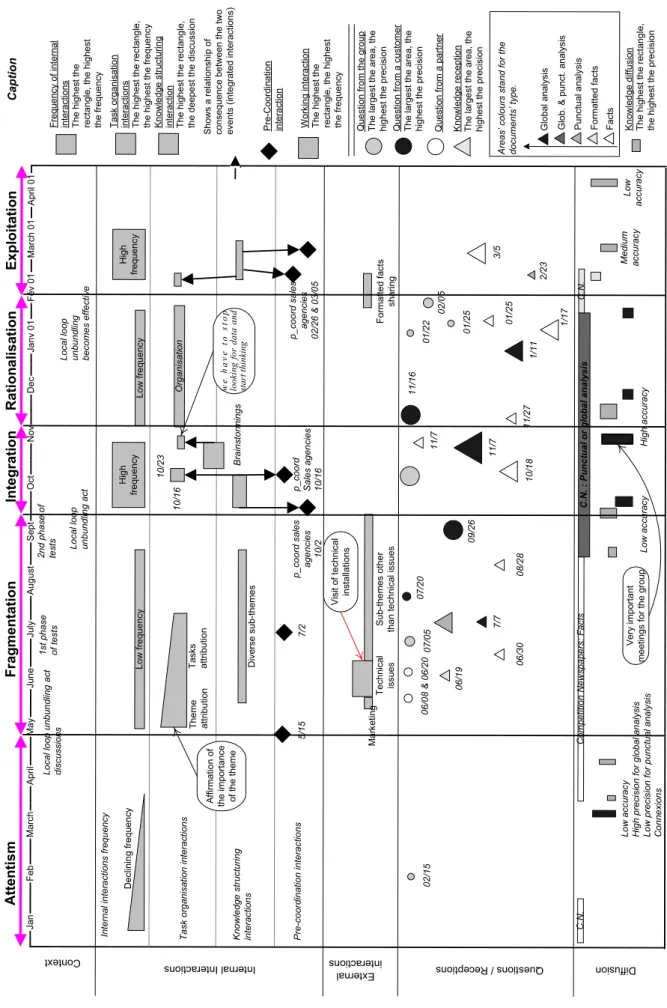

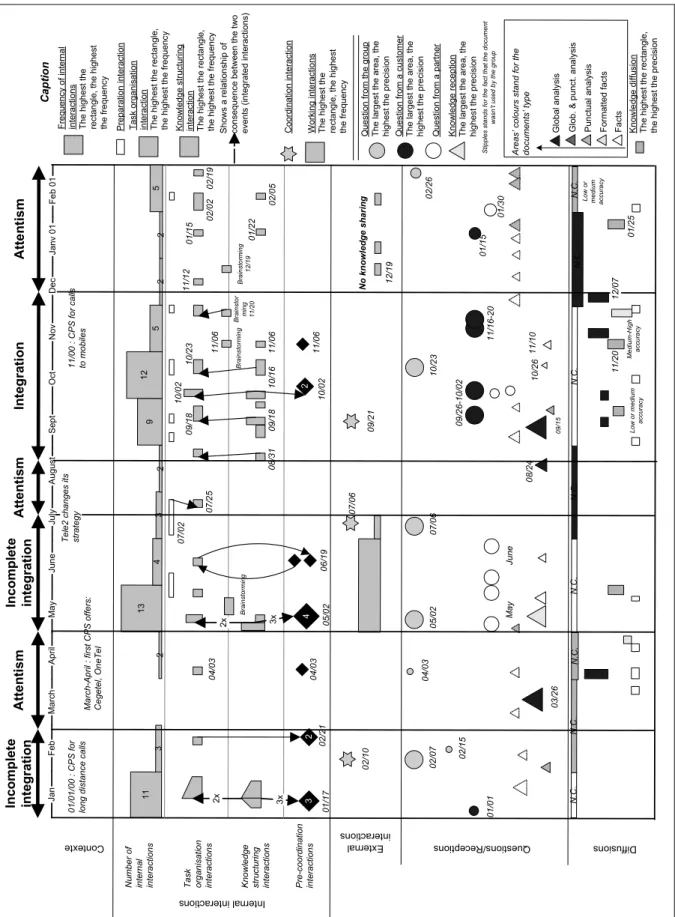

We described the categories’ trajectories with successive phases. Those phases’ graphical repre-sentation ended in a graphical reprerepre-sentation of the whole process, which in turn ended in the determination of its successive phases (see the maps of the processes in Annex A). Those phases were then characterised according to the interactions they contain (cf. Table 4 next page).

Local loop unbundling Carrier preselection

Phase 1

Attentism – 4 months/ January-April 2000

Low frequency of internal or external interactions Few diffusions. Knowledge on the theme is diffused in diffusions concerning other themes (“connexions”)

Incomplete integration– 2 months/ Jan-Feb 00

Huge effort of organisation at the beginning and at the end of the phase. Integrated internal interactions (cf. phase 3 of case “unbundling”)

Few external interactions. Two questions from the group. Received knowledge is not used. No knowl-edge creation

Phase 2

Fragmentation – 4.5 months / May-Sept. 2000

More internal interactions, mainly for the group’s internal organisation. Numerous external working interactions. Diffusions are mainly facts, excepted at the end of the phase.

Æ exploration of a number of sub-themes, creation of fragmented and incomplete knowledge

Æ fragmented interactions: knowledge-structuring interactions mentions different sub-themes and do not lead to task organisation interactions or pre-coordination interactions (cf. next phase)

Attentism – 2 months / March-April 2000

No knowledge-structuring interaction. Few interac-tions at all. Only one question with a very low preci-sion.

Quite frequent diffusions but they are manly facts, or punctual analysis of a low precision Æ low knowl-edge creation

Phase 3

Integration – 1.5 month / Oct-Nov 2000

Frequent and numerous internal interactions. A new type of interaction appears: brainstorming interac-tions that allow for the deepening of a theme.

Internal interactions are integrated:

knowledge-structuring interactions lead to task organisation in-teractions and to pre-coordination inin-teractions.

Diffusions: they are at least punctual analysis of high

precision and high accuracy. The last diffusion entails all the group’s knowledge in a general typology Æ

integration of knowledge

Incomplete integration– 2.5 months / May-July 2000

Huge effort of organisation at the beginning of the phase. Frequent and integrated internal interactions. Then few interactions. No more interaction from 06/19/2000.

External working interactions with a little number of partners. Received knowledge is used in diffusions. Diffusions start to be of high precision. A systematic study of competitors’ offers leads to a first typology of competitors but this typology doesn’t take into account all the group’s knowledge Æ no integration of knowledge

Phase 4

Rationalisation - 3 months / Nov 00 - Feb 01

Only task organisation interactions. They are of low frequency: two methodology meetings for the setting of a continuous study of local loop unbundling

Diffusions: analysis that mainly contain synthesis of

past events or memos of past conferences

Attentism – 2 months / July-August 2000

Two internal interactions, no external interaction, no diffusion, no question to or from the group. Only one received document.

July: the theme is not a priority for the group

August: three of the four group’s members are on

vacation: unwanted attentism

Phase 5

Exploitation – 2 months / Feb-March 01

Integrated internal interactions concerning new com-petitive moves

External interactions: knowledge sharing

Æ old knowledge is used to explain new competitive moves

Integration – 3.25 months / Sept-Dec 2000

Frequent and steady internal interactions; no specific effort of organisation at the beginning of the phase. Integrated interactions. Brainstorming interactions at the end of the phase

No external interactions. Received knowledge of high precision is used.

Diffusions at the beginning of the phase: facts or

punctual analysis of medium precision and low accu-racy. Low knowledge creation

Diffusion at the end of the phase: analysis of high

accuracy and high precision. High knowledge crea-tion. Two global analysis are diffused: integration of knowledge

Phase 6

No 6th phase

Attentism – 2.75 months / Dec. 00 – Feb 01

Few internal interactions. They are not integrated. Unwanted external interactions. Received knowledge is not used. No knowledge creation

3. Towards a model of collective processes of knowledge creation

The analysis of the case of local loop unbundling showed a linear process of knowledge creation:

attentism, fragmentation, integration, rationalisation and exploitation

The analysis of the case of carrier preselection shows a more cyclical process with six phases. The process oscillates between phases of attentism and phases of integration – incomplete at the beginning of the process and complete at the end:

incomplete integration, attentism, incomplete integration, attentism, integration, attentism

So the process of the case “carrier preselection” differs from the process of the case “local loop unbundling” by a couple of issues: it has more phases but they are less varied (three types of phases versus five); it is not a linear process but it oscillates during nine months between atten-tism and integration without reaching complete integration. Nevertheless, they are many simi-larities: phases of attentism look the same; we observed in both cases what we called “integrated interactions” and phases of integrations; the most precise and general diffusions are made at the end of the processes.

We used the comparison of the two cases to generate a global model of knowledge creation processes. We compared both processes phase by phase. In the next paragraphs, we give an ac-count of this comparison and detail phases’ characteristics and utility.

Comparing phases of attentism

3.1.1 Common characteristics

We observed three phases of attentism in the preselection case but only one in the unbundling case. A first similarity is found in the low frequency of internal or external interactions. This shows the passive attitude of the group during phases of attentism. This passive attitude is con-firmed by the fact that the group doesn’t use the knowledge it receives during this type of phase. Regarding the diffusions, the two thirds are “connexions” or are made through the “Competition Newspaper”, an intra-organisational regular support for diffusion that exists during all both proc-esses. So it looks like the group doesn’t try to diffuse its knowledge about the theme during phases of attentism. But it does use opportunities offered by existing diffusion supports created by diffusions concerning other themes. Thus phases of attentism are characterised by a

pas-sive attitude by the group’s members concerning knowledge creation and by an opportun-istic attitude concerning old knowledge diffusion.

3.1.2 Differentiating phases of attentism

Phases of attentism differ through the type of delay they suppose. Mintzberg, Raisinghani and Théorêt (1976) defined three types of delays within unstructured decision processes: scheduling delays, feedback delays and timing delays due to the waiting for “better conditions”. We associ-ated each phase of attentism with corresponding type of delay. The association was based on the internal interactions happening during the phases (cf. Table 5).

Local loop unbundling 3 knowledge-structuring 2 pre-coordination 3 organisation

Preselection 1st phase 1 pre-coordination 1 organisation

Preselection 2nd phase 1 organisation 1 preparation

Preselection 3rd phase 2 knowledge-structuring

1 brainstorming 5 organisations 1 preparation

The second phase of attentism in the CPS case is a scheduling delay: the theme doesn’t have pri-ority. Internal interactions in this phase concern long run issues: the preparation of a document that is due within two months. The third and last phase of attentism is a timing delay: the group waits for “better conditions”, i.e. the occurrence of new competitive events. Internal interactions show the successive sensemaking by the group when new competitive events are detected. The group’s attentism is not chosen but rather subjected: the group has created knowledge that it wishes to exploit but the lack of new competitive events prevents it to do so.

3.1.3 Role of phases of attentism at the beginning of the processes

The phase of attentism in the case of local loop unbundling is appealing. Although it is a time when the group is not very interested by the theme, it is one of the phases of attentism in both cases that contains most knowledge-structuring interactions. Actually, this high level of interac-tions supports the assertion that the group shows an attitude of passive scanning during phases of attentism. The group waits for “better conditions” for action: it punctually discusses some issues related to local loops unbundling in order to detect if those better conditions have happened. Those punctual debates are getting less and less frequent and stop when someone is entrusted with the task of monitoring the existence of documents relating to the theme and of gathering them, thus entrusted with the task of this passive scanning of the competitive environment that characterise phases of attentism.

We found again this allocation of the task of passive scanning to a unique person in the first phase of attentism of the case of CPS. Like in the case of local loop unbundling, this allocation is the last interaction in the phase. Yet there are no anterior knowledge-structuring interactions. However, the phase of incomplete integration that comes before this phase of attentism contains four such interactions. Therefore we assume that knowledge-structuring interactions don’t aim at “testing” if better conditions for action happened – as we mentioned it to explain the role of those interactions within the case of local loop unbundling. Rather they provide the group’s

members with an initial shared knowledge that in turn helps them to make sense of per-ceived competitive events and to decide whether better conditions have happened (i.e. if

those new events are significant).

If so, first knowledge-structuring interactions would help the group to build a first “task envi-ronment” (Newell and Simon, 1972). The task of passive scanning could then be delegated to a unique person so that the group spares its resources. This person plays a role of boundary span-ner, other group’s members being sure that the task environment is shared. Cohen and Levinthal (1990) pinpointed the necessity for a minimal common knowledge between boundary spanners and other organizational members so that the former can transfer the latter new knowledge cre-ated from his environmental scanning.

Comparing attentism and exploitation

Comparing the different phases of attentism also leads us to precise the distinction we made be-tween phases of exploitation and phases of attentism. Indeed there are few differences bebe-tween the phase of exploitation in the case of local loop unbundling and the last phase of attentism of the case of CPS. Nor the lack of diffusion, nor the lack of internal interactions does make a suffi-cient criterion to differentiate both phases since we have shown that a phase of attentism can contain diffusion or internal interactions. The distinction is made upon the content of the interac-tions. In the case of the phase of exploitation, internal interactions are integrated, showing

the group’s willingness to exploit all new data it gathers. We also observed external

interac-tions consisting in a sharing of old knowledge rather than in quesinterac-tions from partners or unwanted interactions.

Comparing fragmentation and integration

Phases 1 and 3 of the process of knowledge creation on CPS arise a question. We showed they are characterised by an integration of the group’s internal interactions but not by an integration of the knowledge it created. Reasons for this incompleteness lay in the study of the numbers of themes quoted or discussed during those phases (cf. table 7, annex B). Sub-themes are sub-sets of knowledge relating to the themes under study. They are a simplification of the problem raised by the need of creating knowledge on a given theme thanks to its division into sub-problems (March and Sevon, 1988). Each sub-problem is a sub-theme. Thus sub-themes are foci of attention (March and Simon, 1958, pp. 149-151) on some types of events relating to the theme. The group’s allocation of attention to sub-themes allows it to deepen its knowledge in them but mitigates its capacity to create knowledge on other sub-themes and its understanding of the remaining events in the environment (Weick, 1995, pp. 100-101).

The study of the number of sub-themes quoted (any internal interaction) in the case of local loop unbundling shows that this number decreases between the phase of fragmentation and the phase of integration. However, the number of sub-themes discussed by the group (knowledge-structuring or brainstorming interactions) remains the same though the sub-themes don’t. More-over, if the number of discussed sub-themes is steady, the total number of knowledge-structuring and brainstorming interactions increases. So does its ratio to the total number of internal interac-tions. Consequently, the transition from the phase of fragmentation to the phase of integration can be summarised by the following trends:

• a more selective allocation of the group’s attention (Cyert and March, 1963) upon some sub-themes, as shown by the decrease of the number of sub-themes quoted during internal inter-actions;

• a collective deepening of those selected sub-themes, as shown by the increase of the number of knowledge-structuring and brainstorming interactions;

• a transition from a logic of individual knowledge creation to a logic of collective knowledge creation, as shown by the decrease of the ratio of the number of discussed sub-themes to the number of quoted sub-themes and by the increase of the ratio of the number of knowledge-structuring and brainstorming interactions to the number of internal interactions.

We can discuss the utility of the phase of fragmentation by the general frame of reference for the theme it provides to the group. This frame helps the group to understand the key issues at stake in the theme and to more efficiently assess the importance of the different sub-themes.

Let consider the sub-themes discussed during the different phases of the CPS process to illustrate this assertion. Discussed sub-themes during the first phase of integration in the CPS process are not the same than the ones discussed during the second phase, nor are they during the third phase. The criteria used to decide which sub-themes should be discussed are not stable. The lack of a phase of fragmentation can explain the group’s inability to achieve a phase of complete in-tegration: in the two first phases of incomplete integration, discussed sub-themes are too numer-ous and thus too resource consuming compared to the group’s resources. Moreover, they are not adequate sub-theme on which to integrate other knowledge relating to the overall theme. This looks like Simon’s limited rationality and March’s local rationality. The phase of fragmentation helps the group to widen the scope of possible alternatives before selecting which sub-themes to discuss.

Comparing phases of complete and incomplete integration

The absence of a phase of fragmentation in the case of CPS leads us to compare the case’s suc-cessive phases of integration (incomplete and complete) with the phase of integration in the case of unbundling. We observe a progressive migration towards the latter: the first phase of incom-plete integration is characterised by a low number of discussed sub-themes (knowledge-structuring and brainstorming interactions) compared to the number of quoted sub-themes (any internal interactions) while the numbers are grossly equal in the last phase of integration. So there is actually a focus of the group’s attention on some sub-themes.

We also observe the migration from a logic of individual work towards a more collective work: the ratio of the number of knowledge-structuring and brainstorming interactions to the total number of internal interactions continuously increases during the three phases of integration (the ratios are respectively 40%, 60% and 78%).

Consequently, we can characterize existing differences between phases of incomplete integration and (complete) integration the same way that we did between the phase of fragmentation and the phase of integration in the case of local loop unbundling: a more selective allocation of the group’s attention, collective deepening of selected sub-themes and migration from a logic of in-dividual knowledge creation towards a logic of collective knowledge creation.

During the two phases of incomplete integration, the fact that internal interactions are integrated shows that the group is willing to deepen some themes it evaluated as important. However, both phases show a lack of knowledge integration. Attempts to integrate created knowledge in a global knowledge of CPS fail: the group twice comes back to a phase of attentism. That is why we called both phases “phases of incomplete integration”.

Thus a phase of complete integration contains a sequence of two sub-phases: a phase of interac-tions integration that comes before and enables a phase of knowledge integration. An interpreta-tion of such a sequence is that the phase of integrainterpreta-tion has to begin by a decrease of the number of sub-themes that the group quotes so that it can deepen its knowledge on the sub-themes it evaluates as the most important ones. The deepening of those few sub-themes (knowledge-structuring interactions) supposes a new organisation of the people engaged in knowledge crea-tion (task organisacrea-tion interaccrea-tion) and by the identificacrea-tion of partners the group can ask for missing data (pre-coordination interactions). This sub-phase of interactions integration allow the group to gather all the “strings of knowledge” it needs. During the second sub-phase, the group uses those strings to gain a global understanding of the theme under study. It is characterised by brainstorming interactions and by a final diffusion that integrate all the knowledge created dur-ing those brainstormdur-ing interactions.

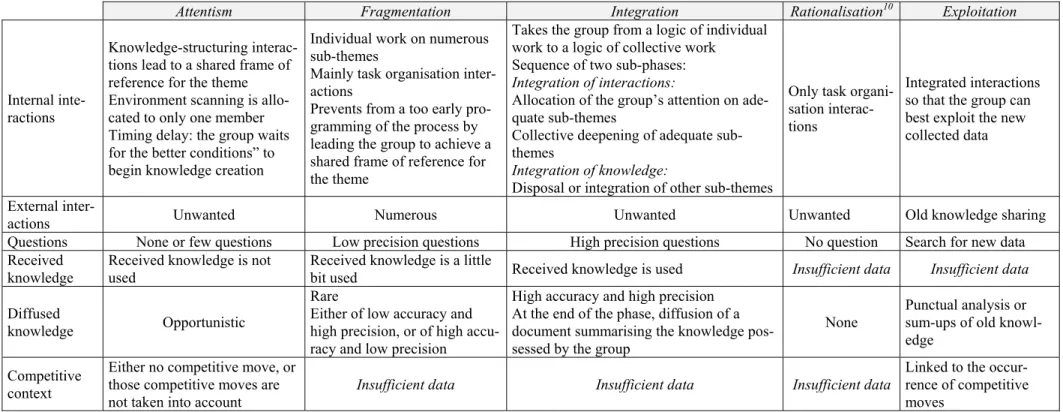

A model of collective processes of knowledge creation

Table 6 next page sums up the phases’ characteristics. They are put in the order of an ideal proc-ess – a linear procproc-ess ending in the creation of a coherent set of knowledge. The five succproc-essive phases are described using five generic variables: internal interactions, external interactions, questions from or to the group, received knowledge and diffused knowledge. Context affects the process too.

Attentism Fragmentation Integration Rationalisation10 Exploitation

Internal inte-ractions

Knowledge-structuring interac-tions lead to a shared frame of reference for the theme Environment scanning is allo-cated to only one member Timing delay: the group waits for the better conditions” to begin knowledge creation

Individual work on numerous sub-themes

Mainly task organisation inter-actions

Prevents from a too early pro-gramming of the process by leading the group to achieve a shared frame of reference for the theme

Takes the group from a logic of individual work to a logic of collective work

Sequence of two sub-phases:

Integration of interactions:

Allocation of the group’s attention on ade-quate sub-themes

Collective deepening of adequate sub-themes

Integration of knowledge:

Disposal or integration of other sub-themes

Only task organi-sation interac-tions

Integrated interactions so that the group can best exploit the new collected data

External

inter-actions Unwanted Numerous Unwanted Unwanted Old knowledge sharing

Questions None or few questions Low precision questions High precision questions No question Search for new data

Received knowledge

Received knowledge is not used

Received knowledge is a little

bit used Received knowledge is used Insufficient data Insufficient data

Diffused

knowledge Opportunistic

Rare

Either of low accuracy and high precision, or of high accu-racy and low precision

High accuracy and high precision At the end of the phase, diffusion of a document summarising the knowledge pos-sessed by the group

None

Punctual analysis or sum-ups of old knowl-edge

Competitive context

Either no competitive move, or those competitive moves are

not taken into account Insufficient data Insufficient data Insufficient data

Linked to the occur-rence of competitive moves

Table 6: Comparison of the five phases of the model of knowledge creation processes along the six variables used for the processes’ description

10 We couldn’t determine the characteristics of the phase of rationalisation because this type of phase appears only once during both processes. In table 6, we sum up the general characteristic of the phase of

4. Conclusion

Our research aimed at understanding how knowledge about an organization’s competitive envi-ronment is created in competitive intelligence services. We worked on this question through the systematic study of interpersonal interactions within and outside such a group. We showed that collective processes of knowledge creation can be described with five distinct phases: atten-tism, fragmentation, integration, rationalisation and exploitation.

It is mainly during the three first phases that knowledge is created. The phase of attentism helps the group to create a shared frame of the competitive environment. The phase of fragmentation is marked by a set of individual creation of knowledge about distinct and numerous sub-themes. Finally, the collective discussion about some of those sub-themes during the phase of integra-tion leads to a global knowledge of the theme.

Knowledge creations occurring during the phase of fragmentation are an essential part of the whole process. They help the group’s members to make informed choices about which sub-themes they have to focus on. This phase prevents the group to choose too many sub-sub-themes compared to its resources or to select inadequate sub-themes for the forthcoming integration of the whole knowledge about the theme.

In this paper, we detailed the characteristics of the different phases of the model by comparing the two processes we studied. Both processes were observed within a three-persons competitive intelligence service. This small size made possible the exhaustive gathering of interpersonal in-teractions. Yet it is a limit of our research as far as generalisation is concerned. We need further research to extend our model’s validity. The model itself can be of great help: the phases’ char-acteristics along six variables can be used to build a faster and more practical methodology based upon the recognition of phases rather than on an exhaustive and systematic collection of interpersonal interactions. Theoretically, our model should fit knowledge creation processes within larger groups with few adaptations. As an example, phases with individual knowledge creation would probably correspond to phases with sub-groups knowledge creation in larger competitive intelligence services.

Processes of knowledge creation are not isolated. They take place in longer organizational rou-tines, such as decision-making or change processes. Thus, the integration of our model with ex-isting models in organization science should get more attention.

Bibliography

Brown J. S., Collins A. and Duguid P., 1989, “Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning”, Educational researcher, 18, 1, pp. 32-42

Cohen W. M. and Levinthal D. A., 1990, “Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation”, Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, pp. 128-152

Cook S. D. N. and Brown J. S., 1999, “Bridging Epistemologies: The Generative Dance Be-tween Organizational Knowledge and Organizational Knowing”, Organization Science, 10, 4, pp.381-400

Cyert R. M. and March J. G., 1963, A behavioral theory of the firm, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

David A., 2001, “La recherche-intervention, cadre général pour la recherche en management?”, in David A., Hatchuel A. and Laufer R. (Eds.), Les nouvelles fondations des sciences de ges-tion, Vuibert, pp. 193-213

Ekstedt, E., 1988, Human Capital in an Age of Transition: Knowledge Development and Cor-porate Renewal, Stockholm: Allmänna Förlaget

Eisenhardt K. M. and Santos F. M., 2002, “Knowledge-Based View: a new theory of strat-egy?”, in Pettigrew A. M. (Ed.), Handbook of Strategy and Management, pp. 139-164

1 Hatchuel A., Le Masson P. and Weil B., 2002, “De la gestion des connaissances aux

organisa-tions orientées conception”, in Rowe F. (Ed.), Faire de la recherche en systèmes d’information, Vuibert, pp. 155-170

Hatchuel A. and Weil B., 1992, L'expert et le système, Economica

James W., 1950, Principles of psychology, New York: Dover Publications

Langley A., 1999, “Strategies for theorizing from process data”, Academy of Management Re-view, 24, 4, pp. 691-710

March J. G. and Sevon G., 1988, “Behavioral perspectives on theories of the firm”, in Van Raaij W. F. and al. (Eds.), Handbook of economic psychology, Kluwer, pp. 369-402

March J. G. and Simon H. A., 1958, Organizations, New York: Wiley

Martinet A. C. and Ribault J. M., 1989, La veille technologique, concurrentielle et commer-ciale, Editions d'Organisation

Mintzberg H., Raisinghani D. and Théorêt A., 1976, “The structure of unstructured decision processes”, Administrative Science Quarterly, 21, pp. 246-275

Newell A. and Simon H. A., 1972, Human problem solving, Prentice-Hall

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi H., 1995, The knowledge-creating company, Oxford University Press, New York

Reix R., 2000, Systèmes d’information et management des organisations, 3rd edition, Vuibert

Scribner S., 1986, “Thinking in action: some characteristics of practical thought “, in Sternberg R. and Wagner R.K. (Eds.), Practical intelligence, Nature and origins of competence in the everyday world, Cambridge MA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 13-30

Weick K. E., 1979, The social psychology of organizing, New York: Random House Weick K. E., 1995, Sensemaking in organizations, Sage

Annex A: graphical representation of the two processes of

knowl-edge creation

The processes are chronologically represented. Different areas stand for the evolution of the occurrence of the analysed categories. From up to down, we represent internal interactions (successively distinguishing their frequency, task organisation interactions, knowledge-structuring interactions, pre-coordination interactions) then external interactions (working in-teractions then coordination inin-teractions). Then we represent questions by the competitive intel-ligence service, received knowledge and diffused knowledge.

In all cases, the height of the rectangles standing for interactions measures their frequency dur-ing the phase. Height of the rectangles standdur-ing for documents (received and diffused knowl-edge) measures their precision; their colour measures the type of knowledge they contain (facts, formatted facts, punctual analysis, global analysis).