THESE PRESENTEE

L'ECOLE DES GRADUES DE L'UNIVERSITE LAVAL

POUR L'OBTENTION

DU GRADE DE MAITRE ES ARTS (M.A.) PAR

ENO-LAFON EMMA LICENCIEE ES LETTRES

FACULTE DES LETTRES UNIVERSITE DE YAOUNDË

BILINGUALISM AND LANGUAGE ACHIEVEMENT OF FINAL YEAR PRIMARY SCHOOL

PUPILS IN CAMEROON

a relationship, which struggles on in the survivors mind towards some resolution which it may never find".

Robert Anderson

'I never song for my father1

To my daughter Petra Kibong LAFON.

Wishing that you'll do more.

To my brothers and sisters, convinced you'll surpass this example.

And last but most important,

To my parents Joseph and Angela LAFON as a token of unqualified love, affection and gratitude for the sacrifies you've made to give your children a sound education. Hoping we'll always be your pride.

This work was made possible by funds from the Ford Foundation "Projet ouest-africain de formation à la recherche en éducation", who sponsored my courses at Laval University and also provided funds for research work and writing out for this thesis.

A special acknowledgement to professor Jean-Paul Voyer, my advisor, who despite the distance, continued to send constructive commentary and guidelines on my work and did the final editing. I would never thank you enough.

I am in debt to professor Francis Mackay who helped to deepen my knowledge and interest on bilingualism, a topic on which he has worldwide renown.

Special thanks to Dr. Omer Yembe who was invaluable in the cons truction and administration of my research instruments and gave my

assistance at all stages of the field work.

My thanks also go to Dr. Amin who helped in the codification and analysis of my data.

Special gratitude also goes to Miala Diambomba, the coordinator of the Projet ouest-africain, who did his best to see that I received the funds for the research and also supervised the final typing and bounding of the work.

Final thanks go to the many friends who encouraged me not to give up, among them are Ayuk Martha, Seydi Becky, Kamanyi Janet, Besane Sekimbaye and Abba, to name only a few.

Table of contents ... 111 List of tables ... v CHAPTER I : INTRODUCTION ... 1 1.1 Ethno-Linguistic F a c t o r s ... 5 1.2 Historical f a c t o r s ... 6 1.3 Language policy in C am er ou n... ® 1.4 The Bilingual Primary School ... 13

CHAPTEP II : REVIEW OF L I T E R A T U R E ... 19

CHAPTER III : RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY ... 37

3.1 Description of s t u d y ... 38

3.2 Description of sample and population of study . 40 3.3 Variables in the s t u d y ... 45

3.4 Measurement instruments ... 45

3.5 Data collection ... 50

3.6 Data analysis p l a n ... 51

CHAPTER IV : PRESENTATION OF RESULTS ... 53

4.1 Analysis of variance. T-Test ... 54

4.2 Pearsons correlation analysis ... 57

4.3 Analysis of c o v a r i a n c e ... 57

4.4 Summary ... 59

CHAPTER V : DISCUSSIONS AND CONCLUSIONS ... 61

5.1 Discussion of results ... 52

5.2 Limitations on generalisability of results . . . 67

5.3 Comparison of results with past studies on bilingualism ... 70

5.4 Conclusions and recommendations ... 71

APPENDIX A: PARENT QUESTIONNAIRE ... 79

APPENDIX B: ENGLISH LANGUAGE ACHIEVEMENT TEST ... 85

APPENDIX C: TEST DE F R A N Ç A I S ... 99

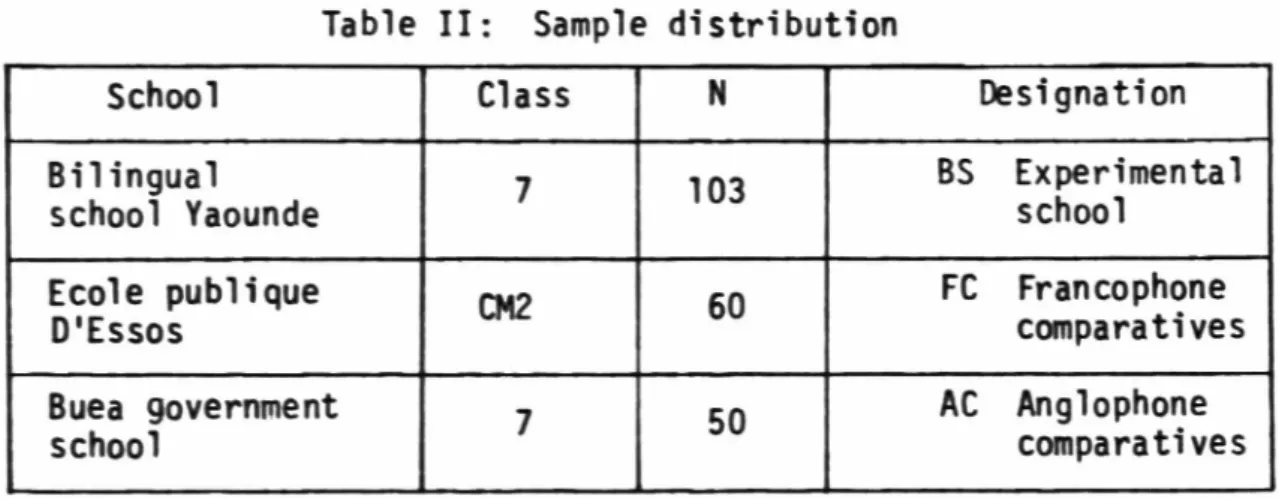

Table II Sample distribution

Table III Sample characteristics

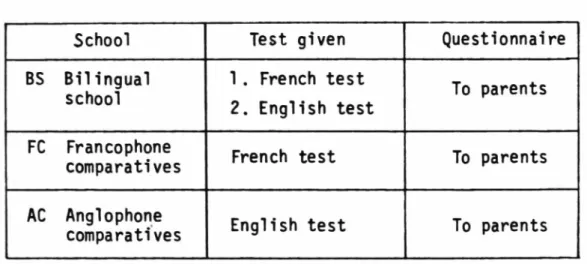

Table IV Administration of research instruments

Table V Mean scores of pilot test

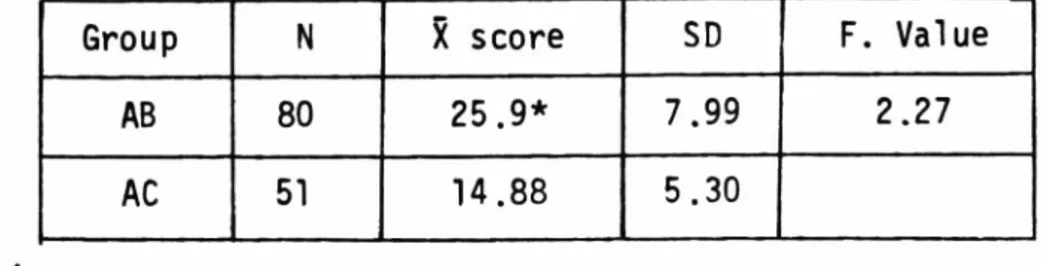

Table VI T-Test comparison of mean scores of AB & AC

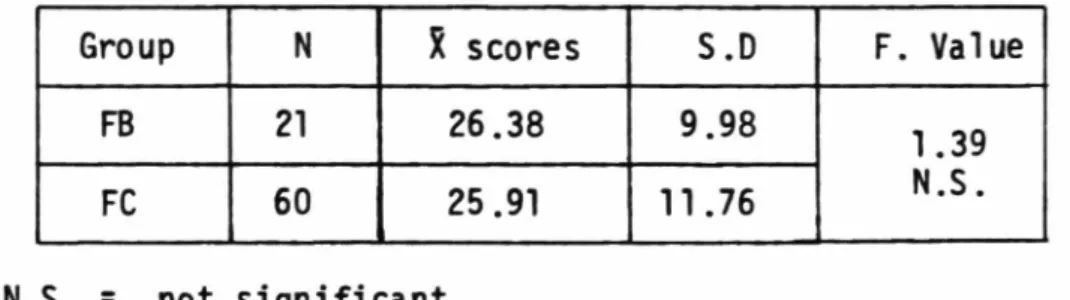

Table VII T-Test comparison of mean scores of FB & FC

Table VIII T-Test comparison of mean scores of AB & FC

Table IX T-Test comparison of mean scores of FB & AC

Table X Pearsons corr. English text with age & SES

Table XI Analysis of covariance for AB and AC; with SES, AGE as covariates for performance in English test

Table XII Pearsons corr. analysis for four groups

This study sets out to investigate the differences in language per formance between pupils in bilingual and non-bilingual schools.

Bilingualism in this study will refer to official bilingualism in Cameroon which recognizes English and French as the two official languages.

This evaluation study will set out to compare the performance in English and French language tests of bilingual pupils in the experimental school, with two comparative groups of non-bilingual pupils.

A statistical analysis of the scores of both groups will provide a basis for comparison and the results of the study.

These results will be discussed and their implications for the de sign of a type of bilingual primary school program appropriate for Came roon will be examined.

This chapter will take a brief look at the bilingual problem as a world phenomenon. It will then go on to examine the language background of Cameroon and those ethno-linguistic, geographical and historical factors which have produced the official language policy of bilingualism in Came roon today. A clear description of the bilingual primary school will be attempted and major terms defined.

Though there are few countries where one would not find some form of bilingual education, people are only grudgingly recognising it for the world phenomenon it is, and bilingualism today still remains a very controversial issue.

Some of the reasons for the bilingual nature of the world as Mac- key (1976) points out is the number of languages. There are about 3000 languages in the world with only 200 countries to harbour them. One does not need to do any calculation to see that many states will have to har bour more than one language. Political frontiers then are rarely linguis tic frontiers. Other reasons are movement of peoples either for migration, trade, studies or pleasures. In each case people are obliged to learn the language of their host country in order to communicate. Other causes of bilingualism could be historical or political events and colonialisation. The problem is further complicated by the fact that despite the great num ber of languages, few international languages dominate. These are the languages of the politically, economically and technologically strong coun tries like Britain, USA, France, Germany, USSR and Japan. Most educated people have a tendency to be bilingual in order to be able to benefit from knowledge transmitted in these languages. In Africa and most third- world countries, to be educated is to be bilingual.

Bilingualism raises political, social and educational pro

blems which are seldom solved by impartial analysis as language is often emotionally linked to the speakers. Most of this controversy is ceptred around the bilingual school. Bilingual schooling has long been looked on as an undesirable alternative to the norm which is unilingual education. The main questions has been: what type of bilingual school is best ? Are bilingual schools as good as unilingual schools ?

Bilingual schools are often born from a social need, hence each school is adapted to a particular context. The combination of languages

involved often differs from country to country, and school programs also differ. This has led to a lot of research on bilingual education from which three main views emerge. The first view, backed by most studies carried out in the early 20th century, sees bilingualism as the cause of various educational, psychological and social problems. Another view pre tends that bilingualism has no effect at all on educational achievement, and a third view considers that bilingualism has positive effects on achie vement and social relations.

The bilingual school is today an expanding institution. In some countries like the United States of America and Canada, the recognized right of some minorities to study their languages, and the maintenance of the official international language creates the bilingual school. Typical among these, are the Spanish, English, and Jewish, English schools in the USA and Canada.

In developing nations an official foreign language is one of the vestiges left by colonial masters. Often, the rise to status of one or more vernacular languages, combined with the need to maintain the interna tional language of the colonial master is the main condition for bilin gualism. In some countries like Cameroon for instance, a complicated co lonial past and a more complicated home-1anguage situation still create another type of bilingualism which constitutionally permits the existence of two foreign languages, English and French. The constitution of the

Federal Republic of Cameroon stipulates that:

"The official languages of the Federal Republic of Ca- meroun shall be French and English". (Art. I Constitu

tion of the Federal Republic of Cameroon, 1961).

What then are the geographical, linguistic and historical fac tors in Cameroon's past that have today led this bilingual language policy which the schools are attempting to implement?

The language situation in Cameroon today, is a consequence of its geographical situation, and historical past.

The United Republic of Cameroon stands on the gulf of Guinea and is bordered by Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, the Congo and Tchad. The rugged nature of the country presents difficulties in communication and contact, and the nearest Cameroon has ever come to a Lingua-Franca is the Pidgin English which is today widely spoken especially in the urban areas. Several large rivers cut across the country among which are the Benoue, the Wouri, the Sanaga, the Mbam and the Manyu. The country is further cut-up by the Buea mountains, the Adamawa and Bamenda highlands. All these geographical divisions have created a multiplicity of climatic regions ranging from the tropical rain forest in the south, to the dry

sahelian zone in the north. With this type of relief, contact between

Cameroonian tribes, especially in the south was practically impossible hence people tended to regroup on small tribes each speaking its own language.

1.1 Ethno-linguistic factors

Cameroon is often called 'Africa in miniature' because it is the melting pot of major african ethnic groups. There are the Bantus who claim kinship with people as far south as the cape. There are also the Sudanese and Fulani in the north, whose race extends as far west as Senegal and Mauritania. There are also Semetic peoples like the Shuwa-Arabs founds all over the African Sahel. There are also the Pigmies, found in many countries of the equatorial jungle. The ethnic groups are so many that Cameroon languages are estimated at over 200. A linguistic survey is being carried out by the research centre for African languages and oral literature (CERELTRA) to establish a linguistic atlas. None of the Came roon languages is spoken over a sufficiently wide area to make it a

of the languages. There are languages like the Bamileke group with over 1 million speakers making it the largest single group and others with less than 100,000 speakers. Cameroon then is a mosaic of small states linguistically and culturally different from each other. In such a situa tion there could be no question of nationality based on language union. Language unity often has to be forged around a foreign language for as Mackey (1979, p. 51) points out "if colonial languages like English, French and Spanish are still officially used throughout the third world it is less out of choice than out of necessity'. Cameroon then has never had the choice even of regional Cameroon languages, as is the case in some African countries like Nigeria where they have the Yoruba, Hausa and Igbo languages and the Central African Republic where they have the Sango. No Cameroonian language except the Bamileke and Beti is spoken over a large area, and even though these languages have many feuding dialectal groups. Unity and communication in Cameroon then is based on the two official languages, English and French with Pidgin English fast becoming a Lingua Franca.

1.2 Historical factors

The language situation in Cameroon today reflects the complex his torical past of Cameroon.

Cameroon was discovered in 1472 by Portuguese explorers who found an abundance of shrimps in the Wouri and named it; "Rio des Cameroes" meaning River of Shrimps. The Portuguese however never settled in Cameroon

but the name they had given to the Wouri river was later adopted by the other colonial settlers, with slight modifications as the name for the whole country. It was known as the Cameroons by the British, Kamerun by the Germans, and Cameroon by the French.

By 1848 the first Christian mission was established in Cameroon at Bimbia by Alfred Saker of the British Baptist mission. The mission house and the church in those days as today, were invariably accompained

by the school, thus English was the first foreign language to be taught in Cameroon. Missions and schools were opened all over along the coast in Douala and even inland, but the British delay in declaring Cameroon a protectorate soon put an end to English influence.

In July 11 1884, Dr. Machtigal, Bismark's plenipotentiory, arri ved in Douala and hoisted the German flag, and the next day he signed a treaty with King Bell and King Akwa establishing German rule. The En glish Baptist missionaries then left, and the Basel mission with German and Swiss missionaries took their place. Their policy was to supplant English with German and limit the influence of dominant vernaculars. Many schools were opened and progress and education were very promising. The German period however ended in 1916 after the first world war with the victorious French and English troups occupying all German colonies. In April 18, 1916, Cameroon was tentatively divided into British and French Cameroon. The melting pot which the Germans had tried to institute va nished, and between 1918 and 1960, Cameroon had developed into two dis tinct linguistic and cultural zones.

French Cameroon gained independence in 1960 and in Oct. 1961, the British Cameroons gained independence by joining the Cameroon Repu blic. Both sides decided to re-unify and form the Federal Republic of Cameroon on February 11, 1961. On May 20th 1972, in another referendum, the Federal Republic of Cameroon because the United Republic of Cameroon still maintain English and French as the two official languages.

Looking at the geographical, historical and ethno-1inguistic background of Cameroon one understands why the Cameroon government had to adopt English and French as the two official languages. They didn't really have much of a choice, since the educational and administrative systems of Cameroon were already in English and French. In order then to maintain the languages of both the anglophone and francophone sections of the country, and to place Cameroon on its way to modernism, two fo reign languages had to be maintened.

When the Cameroon government opted for a bilingual state in 1961, and adopted English and French as the official languages, one of the main aims was, as Tchoungui (1977) points out

"the implicit desire not to arouse ethno-cultural contro versy deriving from the heterogeneity of the new state, and the desire to mould national unity on linguistically neutral grounds"

Bilingualism was to be an instrument of national unity and cohesion. The main problem would be to translate this linguistic choice which was

in fact a political option into the everyday realities of Cameroon life; a country with over 200 home languages. Cameroonians had to feel they belonged to one nation and bilingualism was to contribute in fostering this feeling

"en donnant â chaque Camerounais quelles que soient ses origines et sa langue maternelle, la conscience d'appar tenir 3 une seule et même nation!" (Ngone, 1978).

Nationalism in Cameroon was not to be based on a Cameroonian language as was the case with nation-states like Biafra. National lan guages on the contrary were looked on as dividing forces and despite d e clarations by the government that Cameroonians should be culture cons cious, government policy is silent on Cameroon languages.

Nationalism in Cameroon was to be named around two foreign

languages. The government was faced with some practical problems in the implementation of this bilingual policy; could the government afford to provide services in both languages for all Cameroonians? How then was the bilingual state to function?

Despite watchwords like "harmonisation' which was geared at m e r ging the administrative and educational systems of both sections of the 1.3 Language policy in Cameroon

^By giving to each Cameroonian, irrespective of their tribal origines, the feeling of belonging to one nation (writers translation).

country Cameroon remained a typical bilingual state in which the two sec tions guarded their unilingual nature jealously, and in which there were very few bilingual individuals.

Some Cameroonian scholars argued that if bilingualism was to be a reality English and French must be introduced at primary school level, since children show a greater readiness, motivation and aptitute to learn a new language and arrive at native-like speech. Fonlon in an article "A case for early bilingualism" (1963) used physiological, psychological and lo gical arguments to urge the introduction of both official languages in

the primary school saying that

"My present contention is that if the importance of bilin gualism in our national life has become so primordial, we must begin it early enough to bear it through success fully; in other words, the teaching of English and French together, here in Cameroon, should start right from the very first day that the child takes his seat in the infant school" p . 87.

Others like Tchounqui (1977) Harrison & Wilson (1979) reviewed the Came roon language situation and found that Cameroon still largely functions as two seperate linguistic and educational zones. Some of the realities of the Cameroon state make bilingualism difficult. The anglophone popula tion is just about one quarter of the total population hence French domi nates in official documents, over the national radio station and in the

national daily - The Cameroon Tribune. There are however regional radio stations in which the language of the area predominates, and regional newspapers. Theoretically, official business is supposed to be carried out in both English and French but that seems limited to the presentation of documents in both languages. Since the capital town is in the franco phone section, most administration is done in French, but most offices have a translation service which translates all important documents to English and vice versa. For the rest of the country, work is done almost exclusively in the language of the region either English or French.

the anglophone minority has more bilingual individuals than the francopho nes as they need to speak French to work in Yaounde and Douala the big town. As has been pointed out, when the citizens of a country become bi lingual, they no longer need a bilingual state as they can now function in one language. Cameroon is however still very far from large scale bi lingualism of its citizens. Though there is a good percentage of bilin gual people among the working population of the big towns, this percen tage is negligable when compared to the general population.

The government decided to pass on to the schools the responsibi lity for bilingualism and in 1970 the Ministry of Education launched "Ope ration Bilingualism" whose main aim was to implement early bilingualism.

The main aim of Operation Bilingualism, was to implement the po licy of early bilingualism all over the country. The teaching of the se cond official language had to be introduced from primary school level. In the anglophone section, where English was the medium of instruction, French was to be introduced as a subject, and in the francophone section, English was to be introduced on the timetable.

The ministry realised that such a move needed specially prepared language programs, so the first task of those handling Operation Bilin gualism was the production of entirely new language textbooks. This pro ject was entrusted to two teams of research workers and language teachers working for the Pedagogic Institute for Rural Development - IPAR, with of

fices at Yaounde and Buea.

These teams had to produce new textbooks for both English and French, adapted to the Cameroon area and to second language learning. They had to train language teachers and run experimental and pilot schools.

Yaounde, definite decisions were taken on the implementation of Operation Bilingualism. It was decided:

a) that the 2nd official language will be taught in the last three clas ses of the primary school for five periods a week and given a choice place on the timetable;

b) that by 1981 the two teams handling Operation Bilingualism should be prepared to generalise the teaching of French and English in all primary schools in the country.

Operation Bilingualism then had a definite program of language planning, which as Fishman (1974) points out: "is the methodical activity of regu lating and improving existing languages, or creating new common regional national or international languages". Thus then was a step forward toward regulating the teaching of official languages.

However it is unlikely that all the goals of this project will be met in the near future due mainly to an acute shortage of language teachers.

As the Yaounde team handling Operation Bilingualism points out,

"it will be approximatively forty years before there are sufficient teachers of English to ensure that all primary school children if the francophone provinces have the opportunity to learn English". (Harrison & Wilson, 1979, p. 4).

If the progress of Operation Bilingualism is to be judged from the above statement, then it is a dark pronouncement and Fonlon's (1963), warning might still apply even now.

"Either we gear up ourselves and set about the task vi- gourously now, or in Cameroon bilingualism will remain forever an empty expression".

There has however been some progress. In most of the big town like Douala, Buea, Yaounde, Bamenda etc, the second official language has been introduced in the last three classes of the primary school for most schools. This project is still at the experimental stage and the extent of its effectiveness is still to be evaluated.

The Cameroon government has not limited its efforts to bilingua lism at primary school level only. It would be interesting to take a look at what is being done at secondary school and university level, even

though that is not our main concern in this study.

The teaching of French was introduced in all anglophone secondary schools as a compulsory subject since 1961 but French is used as a medium of instruction for anglophones only in the bilingual grammar school B u e a .

The francophone secondary schools however had always taught En glish as a subject following a French tradition which taught selected m o dern languages in secondary schools.

The teaching of the 2nd official language in Cameroon secondary schools at first was confined to "coopérants" and Canadian aid personel who taught French to anglophones and the American Peace Corps and British volumters who taught English to francophones. Right now however, French and English are taught mostly by Cameroonians graduates of the University of Yaounde. Due to the shortage of language teachers, and the emphasis which the government now places on bilingualism, the Ministry of Education

has been recruiting graduates in mathemetics, history, geography etc. as language teachers. The idea is to have anglophone teachers teaching En glish to francophones, and francophones teaching French to anglophones.

Bilingualism at the university level

With independence in 1961, Cameroon was faced with the problem of the type of university that would satisfy its bilingual status. The bilingual university was the only alternative since Cameroon could not afford for two universities.

Tchounqui (1977) looking at this university has summarized the strategies of language use employed.

Firstly all students have "Formation Bilingue" classes, advanced language courses in the 2nd official language. These courses count as part of their final exams, so they are taken seriously by the students.

Secondly content courses are given in either English or French. The lecturer teaches in the language he prefers, and the students are

expected to be bilingual and follow the courses. In the Yaounde Univer sity then, the obligation to be bilingual rests with the student. In some faculties of the university, like the school of medecine, the teaching of the second official language to the students has been very effective and individual bilingualism of the students is quite high. The proportion of francophone students in the university far exceeds that of anglophones

which according to Gwei (1975), formed only 10% of the university population in 1978. The number of francophone teachers is more than anglophone

teachers.

In conclusion, one can see that definite steps were taken after independence to regulate bilingualism at secondary school and university level. If this policy of dual language instruction is to be maintained at the university, individual bilingualism should not only be assumed, it must be a reality. If one is to believe those who think that early bilingualism is effective then the importance of the bilingual primary school becomes imminent. That is why a study like this one chose to study bilingualism in the primary schools because whatever is done at later stages should be a continuation of what was done in the primary school. What then is the Cameroon bilingual primary school today ?

1.4 The bilingual primary school

In most multilingual countries, the bilingual school is a target for political, social and educational controversy. Who should attend these schools ? How best should the school be organized ? Are they as good as the unilingual school ? are but few of the questions often raised

about bilingual schools. Operation Bilingualism in Cameroon is geared at solving all these problems, for in the long run all primary schools will be bilingual if it succeeds. This study however was not aimed at any of the experimental schools opened by operation bilingualism, but

at the existing bilingual primary schools from which Operation Bilingua lism took its inspiration.

The concept of the bilingual school is often used without dis tinction to cover a wide range of uses of two languages in education.

Often the combination of languages is not defined nor their use in school. M a c k e y (1969)who has attempted a detailed typology of bilingual education, classifies them from single medium to dual medium schools. Before deci ding under what category the Cameroon bilingual school can be classi fied, it is necessary to review the history of bilingual primary schools in Cameroon; especially the Yaounde bilingual primary school which is the experimental school in this study.

The Yaounde bilingual primary school

The Yaounde bilingual school was opened in 1967 thanks entirely to the anglophone community living there. Most of the families working in Yaounde had been obliged to leave their children in former west Cameroon to continue schooling in their first offical language: English. Because this type of arrangement was very inconvenient, the various families affected came together, contributed money and opened a school for their children in 1967. It was only in 1971 that the Ministry of Education

took over the complete running of the school . Most of the financial burden then had been on the parents.

This school then was initially a typical anglophone school trans planted to a French environment and textbooks were identical to those of any primary school in the anglophone section of Cameroon, so why is it

Its bilingual character came about because of a few particulari ties. The parents who had founded this school, living in Yaounde were sufficiently sensitized on the importance of bilingualism for many rea sons. Firstly, Yaounde being the nations capital was in the francophone section of the country, and though in principle the working languages were English and French, they found that a basic knowledge of French was indispensable in Yaounde not only for work, but also in order to live in Yaounde and benefit from services like the hospital, the post office, the market etc. Secondly, a Cameroonian who could speak both English and French was considered an ideal Cameroonian. These parents then decided that French will be taught as a subject from the very first year in pri mary school by a French teacher, using the French language textbooks and syllabus used for francophone pupils. At that time French was not taught in any primary school at all, so this gave the school its bilingual status. Since the children will be living in a French-speaking environment and would have occasion to speak French outside the classroom, the teaching of

French was considered necessary.

A second reason for the bilingual status of the school did not come from the anglophone parents this time, but from some francophone parents. No sooner was an anglophone primary school opened in Yaounde than some francophone parents who personally wanted their children to be bilingual, decided to let them attend the bilingual primary school. But for the French classes, these francophone children had to follow the conventional anglophone primary school program. This would be called in Canadian bilingualism: immersion. These children attend school side by side with the anglophones. This trend has continued and 40% of the total school population today is of francophone background. English is the medium of instruction while French is the first official language for these children.

The important point to note is that in both cases, parents took the initiative. Similar cases can be noted in Canada, specifically the St. Lambert experiment on bilingualism, in which parents in a Montreal suburb wrote and asked for bilingual schooling for their children.

This explains why official legislation on bilingualism is often difficult. Bilingual schools are created out of a social need and cannot be imposed on a community who do not see the need for second language edu cation. That is why bilingual schools differ in their combination of languages and the formula used. In Canada for example, linguists talk of

bilingualism as a situation of a home - school language switch but the situation in Cameroon is slightly different. Bilingual children in Came roon study English and French, both foreign languages. The child switches from the home-1anguage to two foreign languages at school. In Cameroon no home language is taught at school. These bilingual children are really tri-lingual. These children live in a state of continous code-switching. Though they speak English and French in class, they speak mostly Pidgin English with friends outside class, and their Cameroon languages at home with their family. The longterm effects of such code-switching on pupils

speach is obvious. One would expect the phenomenon of interference, trans fer and borrowing to be taking place.

Similar bilingual schools were later opened in most of the big towns like Buea, Douala and Bafoussam. How then can the Yaounde bilin gual school be classified. For the francophone children who make-up 40% of the school population it is an 'immersion' program as the medium of instruction is English their 2nd official language. Mackay (1969), classifies all schools in which a child follows instruction in a language other than his home language as dual medium schools. According to this classification then, one can consider this school as DAT; dual medium

accultural transfer for the anglophone pupils.

This school has had very good performance in the usual end of primary school exams set by the Ministry of Education, such as. The first school leaving Certificate Exam - FSLE, and the common entrance into secondary schools exams. In the FSLE, their performance since 1967 has ranged from 70% - 90%. This has led many Cameroonians to conclude without further analysis that bilingual education has positive effects on performance.

Some terms which will be used frequently in this study will now be clearly defined.

Bilingualism when used in this study will refer to official bi lingualism in Cameroon as specified in the constitution cited earlier. It will refer to the two official languages,English and French, and bilin guals will be the pupils in the bilingual school studying these languages.

Language achievement will refer to the performance scores of children in given French and English tests. The Yaounde bilingual primary school which is the experimental school in this study has already been described.

The terms anglophone and francophone are also used very often. Anglophones will refer to Cameroonians from the English speaking section of Cameroon whose first official language is English. Francophones will be Cameroonians from the French speaking section of Cameroon whose first official language is French.

The purpose of this study

The practical justification for research on bilingual school ing inorganisation of school activities in such a way as to minimise the disadvantages of bilingualism, and maximise its advantages. Innova tions and changes in bilingual schools, are always guided by research which can either be evaluative or operational. There are however a lot of contradictions in results on bilingual studies, because most case studies are quite different from one another. Each bilingual school sys tem often has to do its own research to obtain the solutions to its pro blems .

In a country, like Cameroon, which Vernon - Jackson (1972) des cribed as a "vast laboratory for linguistic experimentation" the impor tance of language research cannot be overemphasized. A Cameroonian

child attending primary school can easily speak four languages a day, switching from one to the other as situations demand. A child will speak English in class, Cameroon language a home with parents, Pidgin English with anglophone friends, and French with francophone friends. This type o f complex linguistic interaction no doubt causes some consequences on

the speech and achievement of the pupils.

Research into the bilingual primary schools in Cameroon, then is important from two points of view. Firstly it will help educators plan a better type of bilingual school structure suited to the complex linguis tic situation in which the children live. Secondly it will help adminis trators take pertinent decisions as to the future of bilingual schools in Cameroon. Results of research done on bilingualism in other countries can hardly be used in Cameroon without prior investigation to see if the Cameroon situation produces the same results.

Since bilingual schools are regarded as an exception and often surrounded by controversy, it is important to carry out research so as to reassure parents that their children would suffer some or no setbacks for being in bilingual schools; and to correct whatever loopholes exist in bi lingual programs.

This chapter will be divided into two main sections. The first section will review literature and past research on bilingualism and pre sent some of the results of this research. The second section will look at some of the theoretical issues raised by bilingualism and come up with research hypothesis and some research questions. Major terms used in this study will then be more clearly defined.

The concept of bilingualism

Spokly (1977) raises one of the crucial questions on bilingualism when he says

"It must be obvious that incomprehensible education is im moral : there can be no justification for assuming that

children will pick up the school language on their own; and no justification for not developing some program that will make it possible for children to learn the standard

language and for them to continue to be educated all the time this is going on", p. 2 0 .

This text assumes that there is a causal relationship between the language of instruction and achievement. This problem is however very complex be cause the determinants of school achievement could be many among which are socioeconomic status, school inputs IQ, age and sex. In a bilingual situation a second language then becomes another factor.

that bilingual education was responsible for lower academic achievement. This could be because as Fishman (1978) point out "The majority of refe rences to this phenomenon are in terms of poverty or disharmony or dis advantages and debits of other lands" p. 42. Even though the bilingual nature of the world and the universality of the bilingual phenomenon are now more readily accepted, research on bilingualism, as will be seen from some of the studies reviewed in this chapter, still produces mixed results. The results of past research will be examined with a critical eye, be

cause due to the many factors which influence achievement, research on bilingualism and language must be well organised for the results to be valid. The domain of bilingual education is broad and populations that are served differ in the combination of languages involved, and the types of bilingual programs used. Research in bilingual education then is con fronted with this lack of uniformity in various bilingual situations and generally it is difficult to compare results from various bilingual situa tions. Recent research on bilingual education is geared at finding out how best bilingual education can be organised to ensure optimum achieve ment.

As pointed out above, due to the many different types of bilin gual schools, it is always very necessary to define clearly what is

meant by bilingualism when talking about it, to avoid ambiguity.

Definitions of bilingualism

Many linguists have differentiated between two types of bilingua lism: individual and national bilingualism. There are then officially bilingual countries like Cameroon, Canada and most African countries in which an African language or languages has been raised to official status and serves alongside the European language as a medium of instruction or administration as a lingua Franca. This does not necessarily suppose the bilingualism of individual citizens. A larger number of bilingual individuals could exist in an officially uni lingual country. The Royal

Commission on bilingualism in Canada, in its report pointed out that most Canadians were divided as to what bilingualism should be. While one new

considered bilingualism a mather of personal concern, another considered it a problem for the state and its institutions, and an evil to be resisted. The word bilingualism then applies to people as well as to countries.

Bloomfield, defined bilingualism as "the native like control of two languages" (1933, p. 56). These earlier definitions which considered bilingualism as synonymous with equilingualism have been broadened as they posed great theoretical problems to research. People realised that bilingualism was a relative concept, and the question to ask was the de gree of bilingualism; the role played by the languages and the consequen ces of their interaction.

Haugen (1953) broadened the definition of bilingualism to include the ability to produce "complete meaningful utterances in the other lan guage" .

Weinrech called bilingualism "languages in contact" and inter ference. He defines languages in contact "If they are used alternati vely by the same person" (1953, p. 1) and interference as "deviations from the norms of either language which occur in the speech of bilin guals as a result of their familarity with more than one language" (1953, p. 1). He points out that in long established bilingual communities

"there is hardly any limit to interference" (1953, p. 81).

MacNamara sees bilinguals as persons who possess at least one of the language skills even to a minimal degree in their second language

(1967, p. 59) Cohen sees a bilingual "as a person who possesses at least some ability in one language skill or any variety from each of the two languages" (1975 , p. 8 ).

Fishman (1971) insists that a bilingual must be diglossic, using one language more in certain situations and the other language in other

Lewis (1965) again raises the dual nature of bilingualism. He considers it an individual and a social phenomenon. For an indivi dual it means the ability to speak two or more languages. For a commu nity it means the recognition of the equality of two or more official languages. He points out that bilingualism can be promoted either by " coding the monolingualism of the minority", or by helping to preserve the integrity of minority groups.

All these different definitions show one of the main problems e n countered by research in bilingualism. Each researcher plans his study' on a particular bilingual situation, based on a definition of bilingua lism he chooses. However the definition of bilingualism given by Weinrech (1953) which considers bilingualism as the alternate use of two or more languages by the same individual will be regarded as appropriate in this study.Language proficiency ranges from the ideal or theoretical nature like ability in both languages, to a passive knowledge of the second lan guage, so it serves no purpose to situate the definition of bilingualism at some level of the continuum.

Linguists and sociologists don't study language from the same point of view. While linguists concentrate on the structural aspects like borrowing, code switching and interference, psychologists concentrate on social interactions. Educationists like psychologist could be interested in the effects of acquiring a second language on the cognitive and

social functioning of the individual , but they will be more interested in the use of languages in education.

This study falls in this domain as it sets out to evaluate the effects of bilingualism on language achievement. The problems of defin ing a bilingual school are like those of defining bilingualism. The term bilingual school is today used to designate various formulas in the use of two or more languages in schools. The bilingual school used in this study has been clearly described in the former chapter. Other terms which will be encountered frequently in this paper will be described.

When language achievement will be used in this study it will be with reference to the performance of the sample population in given lan guage tests. Their scores in these tests will be used as an indice of achievement. A high score will be interpreted as high achievement, and a low score will indicate poor achievement. Achievement will then be synonymous to performance in the language tests.

These test scores will also serve as a tool for measurement. Since this is a quasi experimental study, it involves the comparison of groups on performance, so statistical methods will be used to compare the scores of the comparison and experimental groups. Measurement then will refer to this comparison of scores.

Educational achievement has a wider connotation than language achievement. It will refer to the performance of pupil in all school subject. It will refer to cognitive growth in general. It will some times be used synonymously with language achievement, since language achievement is also an indice of cognitive growth.

Bilingualism and school achievement: some past research

Some writers have attempted to review and summarize research re sults on bilingualism and academic achievement, among which are Peal and Lambert (1962), Cummins (1976, 1979). Many of these studies conclude that bilingualism had detrimental effects on intellectual functioning. A few found no influence of bilingualism on intelligence, and some found a favorable influence of bilingualism on intelligence.

As Peal and Lambert point out, researchers in the early 20th cen tury generally expected to find all sorts of problems associated with bi lingualism of problems associated with bilingualism and usually did. It might be because as Fishman points out "Modern man, and even modern so

cial science (including modern linguistics), has had difficulty conceiv ing bilingualism positively" (1 978, p. 42).

Cummins (1979) in his review of bilingual studies saw that these could be divided into two groups. He noticed from past research that bi lingualism was cognitively and academically beneficial to middle class and high class children from majority language backgrounds, but did often lead to poor academic achievement in lower class minority language children. This same idea has been evoked by Lambert (1974) when he talks o f additive and substrative bilingualism.

Some writers have associated bilingualism with mental confusion, and a split personality without any research proof, but bilingualism could have negative effects if poorly organized.

Jensen (1962) in summarizing studies on bilingualism found that a child's intellectual development may be handicaped by bilingualism for

"Tending to think in one language and speak in the other, he may become mentally uncertain and confused, particularly if he has only a superficial knowledge of one language, or if he is not of superior intellec tual ability". (1962, p. 135).

This assertion is significant from many points of view. It is difficult to say in what language a bilingual is thinking, and the above statement also supposes that if the bilingual were of superior intellectual abili ty, and had a good knowledge of both languages he would avoid mental con fusion. This again points to the additive bilingualism discussed by Lambert 1974.

i

MacNamara (1966) in a study of Irish primary school children con cluded that when a child received instruction through the medium of a weaker language, it led to retardation in the subject matter taught.

These studies argue that since language is the medium of instruction, it is necessary that a child gets a good grasp of language first in order to benefit from instruction in that language. This view has been clearly stated by the U.S. commission of civil rights that

"When language is recognized as the means for represent ing thought and as a which of complex thinking, the

importance of allowing children to use and develop the language they know best, becomes obvious. (1975, p. 44).

One can only conclude by saying that the level of linguistic com petence attained by bilingual children does act as an intervening varia ble in influencing the effects of bilingualism on cognitive and academic development.

MacNamara (1966) studied the effects of bilingualism on the lin guistic and arithmetic attainments of Irish bilingual primary school chil dren and concluded that monolinguals were superior to bilinguals in lin guistic and grammatical skills but there was no difference in vocabulary and self expression. He also found out that bilingualism didn't affect childrens progress in arithmetic provided they were taught all along in one language.

Peal & Lambert carried out a study on the achievement of m on o lingual and bilingual 10 year-olds in Montreal French schools and con cluded that "contrary to previous fundings, this study found that bilin guals performed significantly better than monolinguals on both verbal and non-verbal intelligence tests". (1972, p. 279). The Peal & Lambert study attempted to resolve the inconsistencies of past studies by demons trating that bilingualism could have and did have positive effects on achievement. One of their conclusions was that

"Several explanations are suggested as to why bilinguals have this general intellectual advantage. It is argued that they have a language asset, are more facile at con cept formation and have greaters mental flexibility. (1972, p. 279)

Their study then seems to suggest that bilinguals have a more diversified structure of thought and intelligence. Other studies have confirmed their fundings. Ben-Zeev (1972) found that English - Jewish bilinguals in Montreal and Israel had greater "cognitive flexibility" than monolinguals.

St. Lambert experiment has been carried out in Montreal by Lambert and Tucker. This is a longitudinal study in which these researchers wanted to find out the cognitive, social and attitudinal consequences of immersion education in the 2nd language, through primary school. This experiment

is closely followed and yearly evaluations are done. In an annual evalua tion, Lambert and Tucker conclude as follows

"All told then, by the end of grades 5, the bilingually trained pupils show no handicap whatever on measures of intelligence. In fact there are signs that they may be developing more flexible or creative strategies for pro blem solving than the controls" (1973, p. 156).

Yembe (1979) in a study of bilingualism and academic achievement in the Cameroon secondary schools saw that pupils of the bilingual grammar school outperformed their comparison groups on most tests. He came to the conclusion that "bilingualism and bilingual education in the B.G.S. seemed to exert a more positive influence on the learning of the students dominant or first official language".

Cunmins (1979) points out that most of the studies showing posi tive effects on bilingualism involve pupils whose bilingualism is addi tive. He goes on to ask the question

"Why does a home-school language switch result in high levels of functional bilingualism and academic achieve ment in middle-class majority language children and yet lead to inadequate command of both first LI and second languages L2 and poor academic achievement in many m i nority language children". (U.S. Commission on civil rights, 1975).

This touches some of the theoretical issues which will be examined below.

Most studies seem to find no difference between bilinguals and monolinguals on non-verbal tests, but bilinguals are likely to be hampered on verbal intelligence measures.

initiated by Lambert and other American scholars. Some of these research don't distinguish between summative and formative evaluation. Often a re searcher does one study, writes his report and further evaluations are not carried out. In such cases it is difficult to interprete on the basis of a single research. So far the single experiment where there is perio dic evaluation is the St.Lambert experiment.

Also the tests used are often standardized tests built for unilin- guals. Most researchers argue that since a bilingual posseses two codes his scope of thinking is wider . Are conventional tests capable of bring ing out all these ?

In some of these studies, other variables that might influence achievement are not property controlled and performance is erronously ascribed to bilingualism. Most studies carried out in the early 1920s are

today considered by Peal & Lambert (1962) among others as poorly controlled.

One point is clear however, the use of two languages by the same individual will generate borrowing and interference. The implications of all these need to be examined carefully. The positive fundings on bilin gualism should not cancel the fact that bilingual education should be spe cially planned and controlled for as Fishman points out "Bilingualism will not be spuriously oversold now as it was spuriously undersold (or written off) in the past". (1977, p. 38).

Looking at literature on bilingual education, certain theoreti cal questions are raised. What are the main factors or variables which influence bilingual education programs, and what are the possible outcomes of bilingual programs ? There is no one answer to these questions, but an examination of various theoretical framework used to explain and pre dict bilingual education will give a better understanding of research re sults.

poorly managed. This was mainly because all other variables which affect achievement in general were ignored and all educational outcomes were ascribed to bilingualism. It has also been argued that bilingual programs were drawn as though language learning was the only objective of the pu pils and other subject matters suffered. The use of two languages in edu cation by the same individual, cannot be without some consequences - cer tain writers have proposed various theories which attemps to explain the consequences of this interaction.

MacNamara (1966) in his "Balance Effect" hypothesis argued that a bilingual child paid for his L2 skills by a decrease in LI skills. That competence in one language reduces competence in another. He also saw that when a child received instruction in a weaker 1anguage it led to re tardation in subject matter taught. One can only say that a bilingual always uses one language more than the other. In some cases, the LI of the bilingual might take second place if L2 becomes the language of com munication and work. In such a case LI skills might decrease due to lack of use, but if both languages are used often, that might not be the case. It has been stated, that language being the medium of instruction, a child must master a language well in order to benefit from instruction in the

language. If a child is taught then in a language he doesn't master, it is likely that there will be retardation.

Toukomaa & Skutnabb-Kangas (1977) on the other hand, propose in the Developmental Interdependence Hypothesis that the level of L2 compe tence which a bilingual child attains is partially a function of the type of competence which the child has developed in LI. They argue that: "The basis for the possible attainment of the threshold level of L2 com petence seems to be the level attained in the mother tongue". (1977, p. 28). Some research studies (Cziko 1976, Tucker 1975) have also found some correlation between LI and L2 scores. It can only be said that when one can already read and understand a language, he can easily learn to read another especially if like English and French, the alphabet is the same.

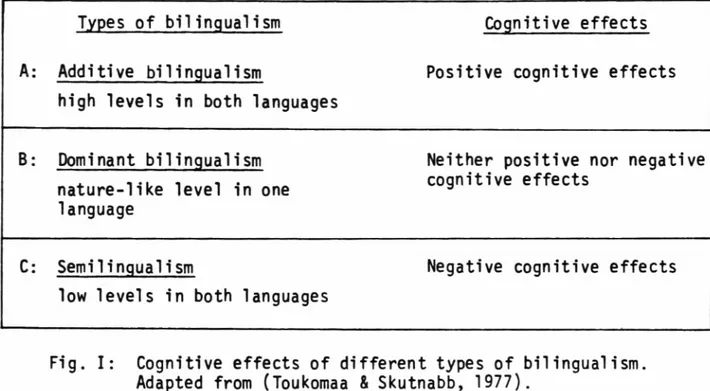

The Threshold Hypothesis (Cummins, 1976, 1978, Toukomaa and Skutnabb-Kangas, 1977) say that there is a threshold of language compe tence which a bilingual must reach in order to avoid the negative effects of bilingualism and benefit fully from instruction in that language. They argue that semi-lingual ism - less than nature-like skills in both languages can have detrimental cognitive and academic consequences. They divide the threshold into three stages which are clearly portrayed in the figure

below.

Types of bilinqualism Cognitive effects

A: Additive bilinqualism

high levels in both languages

Positive cognitive effects

B: Dominant bilinqualism nature-like level in one language

Neither positive nor negative cognitive effects

C: Semilinqualism

low levels in both languages

Negative cognitive effects

Fig. I: Cognitive effects of different types of bilingualism. Adapted from (Toukomaa & Skutnabb, 1977).

They found that groups of migrant children in Canada were characterized by semi lingual ism with its cognitive and academic consequences.

All the above hypothesis go to show that linguistic competence is important in the bilingual child's interaction with his environment. The educational implication of these hypothesis then is that if a bilingual child has to attain optimum cognitive and academic levels, additive bilin gualism which will permits him to attain high levels in both languages must be the goal .

The outcomes of bilingual education however cannot be understood in the light of linguistic factors alone. Uninterpretable data has often been due to failure to take account of other variables that influence achievement like SES, child input and educational treatment.

Many writers have argued on the importance of socio-economic status (SES) on achievement. As Cummins points out it has been observed that children from high and middle class backgrounds show no poor achie vement in bilingual schools, whereas children from poor backgrounds per form poorly.

Beinstein (1961, 1972) was one of the first sociolinguist to de velop a theory on the relationship between linguistic development and so cial class. His theory states the potential intelligence of children from all classes in society is the same, but the context of life, educa tion and communication are different and would influence cognitive develop ment. He points out that since the schools tend to favour the language and environment of the higher SES pupils, these pupils will have an advan tage over poorer SES pupils. The poor performance then of lower SES

pupils is not due to any prior lower intellectual capacity, but to a dif ficulty in adapting to a school environment quite different from the one at h o m e .

This theory looks quite consistent, since what is often called a standard language was formely the idiolect of the elite or of royalty. Children from higher SES backgrounds often have teaching aids at home or an environment where they continually learn. All these put them on an advantage over poorer pupils. As far as language learning is concerned, it has been noticed with pupils learning French in USA and Canada, those from higher classes are sent to France on vacation and summer schools and of course they come back with a better knowledge. These children are

more likely to reach the threshold of language competence. Their bilingua lism becomes additive and they benefit from instruction in both languages.

Another variable which has been known to influence achievement is educational treatment. The school environments, textbooks used, dynamism of the teacher all contribute to achievement.

Pupil input also influences achievement; though some writers think that Initial IQ scores are important, one is more inclined to this variable with motivation. Gardner and Lambert carried out a series of studies on attitudes and motivation and came out with a socio-psycho- logical theory of second language learning which maintains that a success ful learner of a second language must be psychologically prepared to

adopt certain behavior of the other linguistic group. It states that "His motivation to learn is thought to be determined by his attitudes towards the other group in particular and towards foreign people in gene ral". (1972, p. 3).

Carrol (1962) even thinks that aptitude accounts for about 50% success in language while attitudes and motivation account for the other 5 0 % .

Sex and age are other variables that have been supposed to in fluence achievement.

Past research points out that girls are often more advanced than boys in language learning.

A lot of debate has surrounded the subject of age and language learning. What is the ideal age to learn a second language ? Writers like Stern, and Burstall think that there is no optimal age, but the tendency today is to teach the second language from primary school level . Since time is an important element in learning anything, the young child has more time to learn the language.

Looking at all the theoretical issues treated above and the con tradictory findings of past research results, an intergrative model for evaluating bilingual education programs has been chosen. This model sug

St.Lambert experiment. This model tries to take into account socio economic variables, child input and educational treatment variables, and their interaction with achievement. Linguistic variables are not regard ed as the only element in language achievement.

Taking a closer look at the St.Lambert experiment which serves as a model for this study, one notices that some of their objectives were

"we wanted to determine how the home-school language switch would affect their progress in French as well as their standing in English". (1972, p.

8). In their model, they used an experimental design which foresaw various

pretesting and postesting, and educational treatment for both experimental and control groups. They carried out a sociolingulstic survey which collec ted material on pupils SES, age, sex and parents aspirations for pupils educational future. They also administered an IQ test to initially equate the pupils.

The above is a model and the present study has not followed it step by step. The present study used a quasi experimental, posttest only design. It carried out a socio-linguistic survey and attempts were made as much as possible to control for sex, age and SES. All this will be seen

in the next chapter. An attempt has been made in this study to use the intergrative approach of evaluation used by Lambert & Tucker (1972) and others, so that results could be valid within the context of the Came roon bilingual setting.

Language learning in perspectives

Language tests will used in this study to measure achievement. These tests will be described detailly in the next chapter, but they have been built to test the major language skills. A brief look at the language learning process will show later the appropriateness of these tests.

generally follows a certain pattern. He begins with the reception skill of listening comprehension, speaking follows text, later the reading and writ ing skills. For second language learners however, language acquisition does not necessarily follow this pattern. It is often easier for a second language learner to read and write than to speak and sometimes even listen ing comprehension is difficult due to difficulty in understanding the fo reign accent or lack of direct contact with other speakers of the language outside class. We shall take a closer look at the four basic language skills above.

a) Listening comprehension

Teaching language for communication has become the accepted aim of the language teacher. Comprehension of the spoken language, a skill often taken for granted especially by native speakers is of primary importance to the second language learner. This ability to associate sounds to con crete objects and concepts is stressed in modern language methods. This is seen with the increasing used of language laboratories, and the audio

visual method.

b) The speaking skill

The speaking skill is more difficult and demanding for the teacher to teach and is often neglected, or left to a later stage. The best way to develop this skill is to live among speakers of the language, but this is not always possible. Second language learners who come away able to speak are satisfied and more motivated to learn, since the main function of lan guage remains communication. Many supporters of early bilingualism have used the argument that it is easier for a child to master the accent of a foreign language than for an adult.

c) The reading skill