-UNNERSITÉ DU

QUÉBEC À

MONTRÉAL

PROJECTIONS PHOTOGRAPHIQUES HYBRIDES

EXPLORANT LE LIEN

ENTRE ESPACES URBAINS

EN TRANSFORMATION

ET MÉCANISMES DE PERCEPTION

MÉMOIRE

-

CRÉATION

PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE

DE

LA MAÎTRISE EN ARTS VISUELS ET MÉDIATIQUES

OLGA ZARAPINA

Avertissement

La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé

le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles

supérieurs (SDU-522

-

Rév.0?-2011 )

.

Cette autorisation stipule que

«

conformément

à

l

'

article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs

,

[l

'

auteur] concède

à

l

'

Université du Québec

à

Montréal une licence non exclusive d

'

utilisation et de

publication de la totalité ou d

'

une partie

importante

de [son] travail de recherche pour

des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales

.

Plus précisément

,

[l

'

auteur] autorise

l

'

Université du Québec à

Montréal

à

reproduire

,

diffuser

,

prêter, distribuer ou vendre des

copies de [son] travail de recherche

à

des fins non commerciales sur quelque support

que ce soit

,

y compris l

'

Internet. Cette licence

et

cette autorisation n

'

entraînent pas une

renonciation de [la] part [de l

'

auteur]

à

[ses] droits moraux ni

à

[ses] droits de propriété

intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l

'

auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de

commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire

.

»

First and fore most, I would like to thanlrs my direclor of research, David Tomas for the support and Jreedom to experimenl in visu al and written work. Secondjy, I am fore ver indebted to René Daigle, for his patience and ingenui.!JI in motorizing the projector thal is at the base of this research. And to n;y famijy for indulging '19i constant cross-continental search for antiquoted machinery. And lastjy to Nicole Burisch,Myriam Jacob-A/lard, Katie Sinclair and Erin Weisgerbcr, for endless moral support and much needed editing help, as weil as Bérengère Marin -Dubuard for her indispensable translation skills!

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLEOFCONTENTS.... .. . . .. . . .. . . .... . . ... ... ... . . v LIST OF IMAGES . . . • . . . vu

RÉSUMÉ- SUMMARY Xlll

INTRODUCTION . . . .. . .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . .... . . l 9

OBJECTIVITY THROUGH ACCUMULATION IN TEXT AND IMAGE . . . 29 SPACE AND TIME ... ... . . ... .. . .. .. . ... . ... . .. .. . .. . .. . ... ... ... 41

SPATIAL PERCEPTION AND THE PHOTOGRAPHie IMAGE... 87

17.Tl+l7.T2 >P-06-069+04-047-34 ... 157 AFTERWORD.. ... ... .. . ... ... . . . .. . ... . ... ... . ... .... . . .. . ... ... . .. 175 APPENDIX A APPENDIX B APPENDIX C 181 185 199 BIBLIOGRAPHY .. ... .. . ... ... ... ... ... ... . . ... . ... 220

LIST OF IMAGES

INTRODUCTION

20 Michel De Certeau, "Walking in The City" in The Practice afEverydqy Life, ro8 21 Gaston Bachela1·d, "House and the Universe" in The PoeticsoJSpace, 59

22 Hilary Geoghegan and Tara Woodyer, "(Re)enchanting geography? The nature of being critical and the character of critique in human geography" in Progress in Human CeograpJ:y, 206

23 Hilary Geoghegan and Tara Woodyer, "(Re)enchanting geography? The nature of being critical and the character of critique in hu man geography" in Progress in

Human CeograpJ:y, 201

24 Alexandra Molotkow, "Toronto And The Problem of Fun" from Weekend At Bernie Taupin's Blog

OBJECTIVITY THROUGH ACCUMULATION IN TEXT AND IMAGE 30 Susan Sontag, "Melancholy Objects" in On PhotograpJ:y, 74

31 Susan Sontag, "Happenings: An Art of Radical juxtaposition" in Against Interpretation And Other Essqys, 269

32 Michel De Certeau, "Story Ti me" in The Practice oJEverydqy Life, 78 33 Gene Youngblood, "The Artist as Ecologist" in Expanded Cinema, 346 34 Roland Barthes, "The Dea th of the Au thor" in Image-Music- Text, 145 35 Roland Barthes, "The Death of the Au thor" in Image-Music- Text, 146 36 Roland Barthes, "The Death of the Au thor" in Image-Music- Text, 148 37 Michel De Cerleau, "Reading As Poaching"" in The Practice oJEverydqy Life, r6g 38 Max Wertheimer, "Gestalt Theory" in Social Research, 3II

SPACE AND TJME

42 Elizabeth Roberts, "Geography and the Visual Image: A Hauntologïcal Approach" in Progress in Hwnan GeograpJ:y. 390

43 Mike Crang and Penny S. Travlou, "The City and The Typologies of Memory" in Environ ment and Planning D: Socie!J and Space 163

·~4 Michel De Certeau, "Spacial Stories" in ThePracticeofEverydqyLife, rr8 45 Michel De Certeau, "Spacial Stories" in The Practice oJEverydqy Life, II7 46 Yi-Fu Tuan "Introduction" in Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, 3 47 Yi-Fu Tuan "Inti mate Experience of Place" in Space and Place: The Perspective of

48 Yi-Fu Tuan, "Visibility: The Creation of Place" in Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, 16 9

49 Michel De Certeau, "Walking in The City" in ThePracticeofEverydayLife, 95 50 Michel De Certeau, "Walking in The City" The Practice afEveryday Life, 103 51 Yi-Fu Tuan "Visibility: The Creation of Place" in Space and Place: The Perspective of

Experience, 170-171

52 Roland Barthes, "To Waken Desire" in Camera Lucida, 38,40 53 Roland Barthes, "To Waken Desire" in Camera Lucida, 39

54 Marc Augé, "From Place to Non-Place" in Non Places: An Introduction to Supermodemi!J, 87 55 Jeanne Moore, Placing Home ln Context. Journal of Environmental P9'chology, 208 56 Tina Pei!, "Home" International Encyclopedia ofHttman Geograpi]y, r8o

57 Tina Pei!, "Home" International Encyclopedia ofHuman GeograpJ:y, 181 58 Tina Pei!, "Home" International En9>clopedia ofHuman GeograpJ:y, 182

59 Tina Pei!, "Home" International Encyclopedia ofHuman GeograpJ:y, 183

60 Yi-Fu Tuan, "Time And Place" in Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, 183-184 61 Marc Augé, "Anthropological Place" in Non Places: An Introduction to Supermodemi!J, 45 62 Yi-Fu Tuan, "Time And Place" in Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, 198 63 Michel De Certeau, "Walking in The City" The Practice ofEverydC!)' Life, 106 64 Marc Augé, "Anthropological Place" in Non Places: An Introduction to Supermoderni!J, 4·9 65 MarcAugé, "From Place to Non-Place" in Non Places: An Introduction to Supermoderni!J, 69 66 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, "'Association' And The 'Projection of Memories"' in

Phenomenology of Perception, 2 2 - 2 3

67 Yi-Fu Tuan, "Intimate Experiences of Places" in Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, 140

68 Yi-Fu Tuan, "Time ln Experiential Place" in Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, I 2 9

69 Maurice Merl eau-Ponty, " Space" in Phenomenology of Perception, 321 70 Maurice Merleau-Ponty," Spa ce" in Phenomenology of Perception, 308-309 71 Michel De Certeau, "The Art of Me mory And Circumstance" in The Practice of

Everyday Life, 82-83

72 Mike Crang and Penny S. Travlou, "The City and The Typologies of Memory" in Environment and Planning D: Socie!J and Space, 172

73 Mike Crang and Penny S. Travlou, "The City and The Typologies of Memory" in Environment and Planning D: Sacie!J and Space, 165

74 Susan Sontag, "The Image World" in On Photograpl;y, 164

75 Gene Youngblood, "200I:The New Nostalgia" in Expanded Cinema, 144

76 Gaston Bachelard, "The Ho use And The Universe" in The Poe tics aJSpace, 58 77 Marc Augé, "The Near and The Elsewhere" in Non Places: An Introduction to

Supermaderni!Ji, 2I

78 Susan Sontag, "In Plato's Cave" in On Photograpl;y, 15

79 Mike Crang and Penny S. Travlou,"The City and The Typologies ofMemory"

in Environ ment and Planning D: Socie!Ji and Space r66

80 Nadia Atia and jeremy Davies,"Nostalgia and the shapes ofhistory: Editorial" in Memory Studies, r82

81 Nadia Atia and jeremy Davies,"Nostalgia and the shapes ofhistory: Editorial" in Memory Studies,I84

82 Mike Crang and Penny S. Travlou, "The City and The Typologies of Memory" in Environ ment and Planning D: Socie!Ji and Space 165

83 Yi-Fu Tuan, "Visibility: The Creation ofPlace" in SpaceandPlace: ThePerspectiueoJ Experience, 19 2

84 Harriet Hawkins, "Geography and Art, An Expanding Field: Site, the Body andPractice Progress" in Human Geograpl;y, 66

SPATIAL PERCEPTION AND THE PHOTOGRAPHie IMAGE

88 Elizabeth Roberts, "Geography and the Visual Image: A Hauntological

Approach" in Progressin Human Geograpl;y, 387-388

89 Mike Crang and Penny S. Travlou,"The City and The Typologies ofMemory" in Environ ment and Planning D: Socie!Ji and Space, r66

90 Roland Barthes, "The Photographs Unclassifiable" in Camera Lucida, 6

91 Susan Sontag, "In Plato's Cave" in On Photograpl;y, r6

92 Susan Sontag, "In Plato's Cave" in On Photograpl;y, 4-5

93 Elizabeth Roberts, "Geography and the Visual Image: A Hauntological

Approach" in Progress in Hu man Geograpl;y, 392

94 Elizabeth Roberts, "Geography and the Visual Image: A Hauntological Approach"

in Progress in Human Geograpl;y, 389

95 Elizabeth Roberts, "Geography and the Visual Image: A Hauntological Approach"

in Progress in Human Geograpl;y, 397

96 Mike Crang and Penny S. Travlou, "The City and The Typologies of Memory" in Environ ment and Planning D: Socie!Ji and Space 174-175

97 Susan Sontag, "The Image World" in On Photograpi;y,I67 98 Susan Sontag, "Melancholy Objects" in On Photograpl;y, 57

99 Gene Youngblood, "Synaesthetic Synthesis: Simultaneous Perception of

Harmonie Opposites" in Expanded Cinema, 8r

OnPhotograpf:y,I25-!26

l 04 Susan Sontag, "Photographie Evangels" in On Photograpf:y,I24

105 Michel De Certeau, "Walking in The City" in ThePracticeofEverydC!JLife, lOI l 06 Elizabeth Roberts, "Geography and the Visual Image: A Hauntological Approach"

in Progress in Human Ceograpf:y, 388

107 Yi-Fu Tuan, "Visibility: The Creation of Place" in Space and Place: The Perspective ofExperience, r6r

l 08 André Bazin, "The Concept of Present" What ls Cinema, Volume 1,96 109 Susan Sontag, "Plato's Cave" in OnPhotograpi:J,n-r8

llO Mike Crang and Penny S. Travlou, "The City and The Typologies of Memory" in Environment and Planning D: Socie!J and Space, r68-r69

111 Gilles Deleuze, "From Movement Image and Its Varieties" in Cinema 1: The Movement-lmage, 61-62

112 Susan Sontag, "Melancholy Objeets" in On Photograpf:y,8r

113 Gene Youn~blood, "Synaestheties And The Kinaesthetics: the Way Of All Experience' in Expanded Cinema, 105

114 Gene Youngblood, "Technoanarchy: An Open Empire" in Expanded Cinema, 415 115 Gene Youngblood, "Videographie Cinema" in Expanded Cinema, 323

116 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, "Space" in Phenomenology of Perception, 313 117 André Bazin, "Cinema And Exploration" What Is Cinema, Volume 1, 163 1 18 Gilles Deleuze, "Iclentity of Image and Movement" in Cinema 1:

The Movement-Image, 57

119 Gilles Deleuze, "Identity of Image and Movement" in Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, 59-6o-6r

120 Marcel Duchamp, "Nucle Descending The Staircase, No2" 1912

121 Barbara andJoseph Anderson, "The Myth ofPersistence ofVision Revisited," in Journal of Film and Video

122 123

124

125

Gilles Deleuze, "The Reverse Proof" in Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, 68 Gene Youngblood, "Synaesthetic Cinema And Extra-Objective Reality" in Expanded Cinema, 122

Gene Youngblood, "Synaesthetic Cinema And Extra-Objective Reality" in Expanded Cinema, 126

Gene Youngblood, "Cinema And The Code" in Leonardo. Supplemental Issue, 28-29 126 Gene Youngblood, "Syncretism and Metamorphosis: Montage as Collage"

1 '27 Susan Sontag, "Melancholy Objects" in On PhotograpJ:.y, 68

1 '28 Gene Youngblood, "Cinema And The Code" in Leonardo. Supplemental Issue, 28 1 '29 Gene Youngblood, "Syncretism and Metamorphosis: Montage as Collage"

in Expanded Cinema, 86-87

130 Gene Youngblood, "Syncretism and Metamorphosis: Montage as Collage" in Expanded Cinema, 85

131 André Bazin, "The Evolution of The Language of Cinema" in What ls Cinema, Volume 1, 34

13'2 Marc Augé, "Introduction" Non Places: An Introduction to Supermoderni!JI. xiii 133 André Bazin, "The Evolution of The Language of Cinema" in What Is Cinema,

Volume 1, 35-36

134 André Bazin, "An Aesthetic of Reality" What Is Cinema, Volume 2, 28 135 André Bazin, "An Aesthetic of Reality" in What Is Cinema, Volume 2, 32 136 André Bazin, "An Aesthetic of Reality" in Wh at Is Cinema, Volume 2, 37

137 Gene Youngblood, "Cinema And The Code" in Leonardo. Supplemental Issue, 29 138 Gene Youngblood, "Synaesthetic Cinema And Extra-Objective Reality"

in Expanded Cinema, I2 7

139 André Bazin, "Theater And Cinema- Part Two" in What Is Cinema, Volume 1, 99 140 André Bazin, "Painting And Cinema" in What Is Cinema, Volume 1, r66

141 André Bazin, "Behind the Decor" in What Is Cinema, Volume 1, !02 14'2 André Bazin, "Painting And Cinema" in WhatlsCinema, Volume1, 165 143 Gene Youngblood, "The Artist as Ecologist" in Expanded Cinema, 348 144 Gene Youngblood, "Intermedia Theater" in Expanded Cinema, 366-167

145 Delphine Bénézet, "Varda 'sEthics of Filming" 71, "Aesthetic And Technique" 42 in The Cinema of Agnès Varda: Resistance and Eclecticism

146 Delphine Bénézet, "Agnès Varda: A Woman Within History" in The Cinema of Agnès Varda: Resistance and Eclecticism, 30

147 Delphine Bénézet, "Poetics of Space"in The Cinema of Agnès Varda: Resistance and Eclecticism, 107

148 Delphine Bénézet,"Poetics of Space"in The Cinema of Agnès Varda: Resistance and Eclecticism, 103-104

149 Gene Youngblood, "The Artist as Ecologist" in Expanded Cinema, 349

150 Gene Youngblood, "Cinema And The Code" in Leonardo. Supplemental Issue, 30 151 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, "Space" in PhenomenologyofPerception,338

17.TI+I7.T2 > P-06-069 + 04-047-34

158 Aerial view of the construction site. Top Photo A: Olya Zat·apina, April 2015. Bottom Photo B: Google Maps

160 lnterior and Exterior Views of Exhibition Space at 6833 Rue De l'Epee Photos A, B, C: Olya Zarapina, June, December 2014

Photos D,E: ImmoCan, Eric Gross

162 Camera Obscura. I7 .TI+I7 .t2 > P-o6-o6g + 04-047-34 Exhibition View Photos A,B: Olya Zarapina. December 2014

164 Scanned photo-film included in 17 .TI+I7 .T2 > P-o6-o6g + 04-047-34 166 Strip-slide projector. 17.Tr+r7.T2 > P-o6-o6g + 04-047-34 Exhibition view 168 17.TI+I7.T2 > P-o6-o6g + 04-047-34 Exhibition View, December 2014 170 Photo A: Outremont Roundhouse, 1938. Scott Henderson persona! collection

Photo B: Deconstruction of the Railyard, 2006, Michael Berry 172 17.TI+I7.T2 > P-o6-o6g + 04-047-34 Exhibition Poster

AFTERWORD

176 Harriet Hawkins, "Geography and Art, An Expanding Field: Site, the Body and Practice Progress" in Progress in Human Geography, 66

178 Susan Sontag, "Godard's Vivre Sa Vie" in Against Interpretation And Other Ess9Js. rg8 179 Gene Youngblood, "Synaesù1etic Cinema:The End ofDrama" in Expanded Cinema, 76

<<HOME>> L'ESPACE URBAIN

PHOTOGRAPHIE FILM INSTALLATION

PROJECTION

RÉSUMÉ

Mon approche de la création artistique est à la croisée des chemins entre l'anthropologie, l'urbanisme, la géographie créative et l'art. Cette interdiscipli-narité me permet d'explorer le rôle du document photographique dans la rela-tion entre le temps, la mémoire, la nostalgie et leurs effets combinés sur notre perception des espaces ordinaires.

La recherche réalisée lors de la maîtrise en arts visuels et médiatiques à l'Université du Québec à Montréal, qui culmine en l'exposition 17.TI+I7.T2 > P-06-069 + 04-047-34, prend pour objet la ville de Montréal, ses cartiers et leur transformation architecturale progressive et permanente ainsi que la mutation des attitudes des habitants. Ce phénomène, qu'on le nome "gentri-ncation", progrès, ou tout simplement changement inévitable, n'est absolu-ment pas réservé à Montréal. Il est étroitement lié à l'économie de marché et concerne les villes qui se développement selon les dynamiques spécinques qu'il instaure, ce qui est largement abordé dans la culture populaire aussi bien que dans les écrits universitaires.

Le site qui est au centre de cette recherche est l'ancienne gare de triage du Canadien Pacinque. Lorsque je l'ai découvert pour la première fois, c'était un terrain semi-abandonné dont les résidents du quartier avoisinant avaient fait une sorte de parc communautaire informel. Aujourd'hui, c'est le chanter de construction du futur campus de l'Université de Montréal et de sa résidence universitaire qui y a pris place. En une dizaine d'années, cet endroit, un micro-cosme à l'image d'un phénomène global, subira une transformation non seul e-ment de sa forme spatiale, mais celle-ci affectera aussi la composition socio-économique de tout le voisinage.

17.TI+I7.T2 > P-06-069 + 04-047-34, nommé d'après les numérota-tions des lots en transformation et des numéros de permis de construire, rend compte de la métamorphose spatiale en regroupant plusieurs cadres temporels du même lieu de manière à amplifier l'expérience du présent en faisant écho à la nostalgie du passé. Mon installation photo-filmique rassemble des photogra-phies amateurs et des photographies d'archives, du cinéma expérimental et du cinéma élargi (expanded cinema) ainsi que le caractère in situ de l'installation qui explore la capacité de l'image photographique à appréhender la perception individuelle et collective de ce lieu ordinaire et particulier.

C'est par l'accumulation de sources visuelles et littéraires variés que ce texte qui accompagne l'installation vise à accentuer la question des attitudes envers notre environnement en devenir. Individuellement, ces transformations spa-tiales sont à peine perceptibles. Rassemblées, elles forment les fragments d'une culture en mouvement.

URBAN SPACE PHOTOGRAPHY FILM 1 N STALLATION PROJECTION MEMORY

SUMMARY

My overall artistic approach is positioned amongst anthropology, urb an-ism, creative geography and art; this interdisciplinary focus permits me to explore the role of the photographie process in documenting the relationship between time, memory, nostalgia, and their combined effects on our percep-tion of ordinary spaces.

More specifically, the research clone as part of the maitrise en arts visuels et médiatiques at the Université du Québec à Montréal and culminating in I7.Tr+r7.T2

>

P-o6-o6g + 04-047-34 exhibition is really about Montréal, its neighborhoods, and their ongoing transformation in architecture, as well as in the attitudes of the inhabitants. This phenomenon-gentrification, or progress, or inevitable change-is in no way exclusive to Montréal. lt is closely tied to the free-market economy and the cities that exist within it, and has already been extensively discussed in popular culture as well as in academie writing.For my part, the site that became the focus of this research was once a Ca -nadian Pacifie Rail yard. At the time I encountered I, it was a semi-abandoned lot casually used by the neighboring residents. It is currently a construction site for the future campus and student residences of the Université de Mon-tréal. Within a decade, this place, a microcosm of a global phenomena, will go through a major transformation that will not only affect the appearance of the space itself, but also the socioeconomic makeup of the surrounding neighborhoods.

J7.TI+I7.T2 > P-o6-o6g + 04-047-34-named after the municipal lots being transformed and the permit numbers authorizing the construc-tion-documents the site's spatial metamorphosis by bringing together mul-tiple time frames of the same location as the means to amplify the experience of the present and echo the nostalgia of the past. My photo-filmic installation is an amalgamation of amateur and archivai photography; experimental and expanded cinema; as well as architectural site specifie installation that explores the capacity of the photographie image to capture individual and communal perception of a particular but ordinary location.

Through accumulation of various visual and literary sources, this text and the accompanying installation aim to accentuate and question our atti-tudes toward our changing surroundings. Individually, these spatial transfor-mations are barely perceptible, but accumulated together they become frag -ments of the changing culture.

108 WALKING IN THE CITY

.

;ii=

~&=====

'l'he d!~P.ersiQ.ll ..

oJ

storit.!i JJ.c.iul~ tp the dispersion Qf the memQra~~w:!_rÀ-nd

Ü1

fru;Lroemorx

is..a

sort of anti-m.Ym~~ments of

it

come out in legends. ()bjects ~nfl_'!."or~~o h_ave hollow places in which a past _sleep_s, as in Jlte _ever d.~ ~c.ts ?f walking:-eàtîrig7 i g(5îfigiobed, lnwhicl}_ancient revolutions slumber. A 'memory iso nlf a Prinèëê

har

~ing_;

ho ~~a~s jn~>

~J

~g

enough.J..Q.a;~~~

·

Sleeping 1B

~;ttlie

~

o

urwordle~~~ories.

"li

re, there us-edü;""bea -bài<erf--.....

~

here--e-ld

-

11ld·y

-

Oupu1

usedQ...)jy;-.'

-

I

Îi~

strig}n here""tharthe-_ p!aces e~ tht:.Pr:~encçs!!f

diy!!fse absences. What can be se~Jit:sjgnates-wha.t..is-no ~onger_~~~ " Ol:! s~t:_ h~ !here used to be . . . " but it cal}_ n..2 .J.2.nge.r..he...se~o. DemonstraJives indicate the in--vtslbie identities of the visible: it is the ve definitio_!! of .!Jllace, in act, - atitis composed b these series of displacements and effèëtSàmong "flielrimen .. tëd._m hat-form itÏwd that-it -playsM thësèfiïOVïïïg-_.... - -- - - - -- --...:::>

layers:

___;:;_;~lU!-'L~...w.;s~to~that place ... . lt's persona!, not interesting to r

a

ïith

~Î

·; wfiàï-givèsa n·eighboëtü.iQd its char-• actë"r:" The re is no lace that is not hauntedb'Y;t;;;y

different spirits hiddenther

~

lence,

spii="iïS o-;}ëëiin-:fn"voke" or not. Haunted places 'are'the'only()iiëSj;ëople can live in-

.

-.:...---··

-·-

--

--

.~ .. ·.'-.. ~

..

..

. - ··

- - - -

-·--,;.,·_."spirits," them selves broken into pieces in like manner, do not speak any more than they see. This is a sort of knowledge that remains silent. Only hints of what is known but unrevealed are passed on "just between you and me."

l

-

Places are fra mentar and inward-turning histories, pasts ·that ~ are not allowed to read, accumulated times a ca ëun oldëefbut like, .!Iories held

in

_

r:

~~

mai

n

ms

~

in

ane~ig;ila

t

ië

state..:sy

mbol

~

1

encysted in the pain o_r.l

~

su

~(2

f

.!b.:_b~

dy

.

"~fee!

gooa hei-ë':

'

0t~

--·

well-being un r-expres•ed iR the language

it

appears 1n 1 e a-neetlng , iîimméris a spatial practice.----<·

59 howe and universe

... .._ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ _ . . . _.._. .... _ _ __ I..: ..... _._ L - - . 1 . . ! .. ~---7 :-...::t.D.r.nA--.b A., • 6 ..;.. -1 ..1 ----....! -... L-...-...-....____-....)_ _ __ _

1

1 1 ,w ;,

T'

1

,

8

....,,

--~W

~,

1

...

_.._ "In _a_pass~ge like this, ima~na_:~on,. ~mory and perception

e~an~ft;,ncti?ns· The i!Dage_is creatsd thr~g!; co-opet:_a· tion between real and unreal, with the help of the functions o!'-tlïe

~

al a

mf

--

l

!J.

~

linrëàl. -

To-

us~

y the

i

mplem~n

u~

dialèctiè:al logic forst

~g

,

not this alternative, but thisfusion, of opposites, would be quite useless, for they would produce tlle anatomy of a living thing. But if a bouse is a living value, it must integrate an element of unreality. Ali values must remain ·vulnerable, and those that do not are g.ead.

206

l M ?

'pd

Notwithstanding the different

conceptions of

s

ubjectivity

at

play

,

this focus

on

!ife knowledge

represents

a

disciplinary return to

a

longer

trajectory

of 'intu

_

iti

_

on' as advocated

by the

humanistic

geographers such as Seamon

(

1979),

specifically 'the

nature

of

noticing

and

a

ttention

'

imbricated

-

in

our encounters and

mer~gings wlfh

·

iïlë

·

w

-

orld

.

-

It

is the in-betweenness

of

the

se

relàtionships that is

interesting

here

,

nal!_l~ly

the

_

communicative

rel_

ationships

between things that evoke feelings of love, ca re

ar1Tattâêl1mënt

.

.

T

his

attention

helps us move

away

from causal relationships of power,

thereby

estabrishïng

à

n

·

émotional and ethical

cori1ëxt

fo

_

r

_

o

ur relations

.

-

This

counters -

the

normative

detached role

... of

the

academie

.

ln

challenging a

disregard for

what

lies

at

the mar

-gins

of

sense,

researchers

are reguired

to

re alize

that

'we are

only part of the

world, ofthe

ma_&

mg

of

place

,

for

the world

materialities

e

1eves in us

as

muchas we

(emotions)

believe

in

it'

(Dewsbury,

2003:

1908)

.

Witnessing

immateriality

is

not

easy

because

it 'calls

us to

betray our roots in

habitable

modes ofthinking'

(p.

1923)

,

but

it is a worthwhile

task

as we

now

outline

in discussing the benefits

of

adopting~Wright's

work

is instructive for thinking

through enchantment as

he

attends

to both the

pleasurable

sense of

mystery

and its

simulta-neous

si

nister

edge. Attentive

to the

'disrepute

in which subjectivity is often

held in

scientific

circles' (Wright,

1947

:

5)

,

he

stressed

the

criti-cal

distin

è

tion

betw~en illu.

s

ion

an

d

-'

ëîéï

ii

s'

ioo

~

"'

focusing on'

aesthètié

imagiiling'

,

a process thàt

encompasses

·

the

.

communication of

the results

ofOür lmagi

-

n

i

ng

.

It is

theref~re

'entirely legiti-

·'

ma

'ïé

-

i

oë

iiiïchand add

colour

and vividness

to

the

style of an otherwise

objective

geographical

exposition' (p. 8) as

this brings

the audience

'down

to earth

from

the lofty

observation

point

of

the

objective', allowing

them to

'see

and fee)

through

our eyes and

feelings'

(p

.

9)

.

The aim.

then

,

is not to de lude

.

the

audience,

but to rende.L

teaching and writing

more

evocative and

thus

powerful than they might

otherwise

be

.

Wright's

'geosophy' was an

importa

-

nt

ante~cedent

to

a

broader humanistic

geography

con-cemed with

the intimacy of people-place

relatï'ons

.

To provide but

a brief account of

this

field

is neces

sa

rily to

do a

disservice to the

diverse character of a rich

and fragmented

gath-ering of

philosophies

,

methods

and substantive

s

tudies

.

Broadly

s

peaking

,

humanistic

geogra-phy developed

as a critique of

the

'peop1eless'

s

patial

science of

the 1950s,

we

might

say a

dis

~

ench

-

a~

tê

d

appr;ach

th

at

.

w~~

insensitive to the

humanity

of

both

the geographer and

those

under

study.

To

counteract

the reification

of

human

subjects as

'

little more than dots on

a

map

,

statistics on a graph

or numbers in

an

equation' (Cloke et al.

,

1991: 69)

,

humani

s

tic

geog

raphers looked to phenom

e

nology

and

ex

i

ste

ntialism

for inspiration

.

Central

to

this

move was

'

reawakening a sense of wonder

about

the

earth and

its places

'

(Rel

ph

,

1985

:

1

6)

by

attending

to direct human

experience;

···-

. . ---- ···--··· ·-- --- ... -···-

-fostering

a 'compassionate

mte 1gence t

at

seeks

to

see

things in

and

for themselves'

(p

.

16). These

geogra

phers

were

in

the

process

JUl\"E 6, 2011 ·2:05PM

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Montreal is a trading post where you exchange your hop es and dreams for a mansion th at costs 25 cents a mon th. Vvhen you get there, angels gently unburden you of your ambitions and band you

INTRODUCTION

Severa! years after moving to Montréal, I came across the previous passage on an internet blog. The twenty-nve-cent mansions and Jack of am-bition are, of course, an exaggeration. However, in this humorous and poetic way, the author explained why so many people from ali over Canada, North America and the world, despite apparent economie and linguistic obstacles, are drawn to this city. During the last few decades, the city's affordable hous -ing made up for employment difnculties and created the now notable artistic hub. This allowed its residents to pursue unostentatious work plus the time and space for artistic endeavors, often fueled by creativity desires over mon-etary aspirations.

For my part, I did not move to Montréal for school, or for work, or for people. I did not know anyone in the city and did not have a job lined up. I moved here because it felt more like home than anywhere I had lived or visited before; this remains true today. By that point in my !ife I was already interested in the effects places had on their inhabitants, and conscious about which places fit with my lifestyle, poli tics, and citizenship restrictions.

I was born in Kyiv, Ukraine in the last decade of the Soviet Union, when values regarding property and community were rapidly changing. I spent my childhood shuffled between two cities and three different resi-dences. Shortly before I turned twelve, my family immigrated to Edmonton, Canada. A place which if Augé ever visiting I am sure he would agree when I say th at the wh ole city is a non-place', constructed according to sorne kind of permanent temporality. Ten years and another three residences later, I left as soon I could. After sorne wandering around the world, I eventually settled clown in Montréal.

1 ln this context, 1 use the lerm "non-place" to reference of not only transient physical locations, but also fleeting attachments to a permanent place.

r

propose that a city of inhab-itants with predominantly flexible spatial attachments can be as much of a non-place as, for example, a historie train station, beloved by its community.The empty spaces and the cheap rents are losing their signiflcance and are being replaced by condos occupied by the new ambitious professional class. The places that once fostered community and creativity are capitalizing on their locations and their inhabitants move on as the cycle repeats itself in a new place.

According to my mother, there is nothing more permanent than the temporary.

Having to adapt from an early age to different places and remark-ably different cultures clid not necessarily make me long for home or a place of my own. However, while often foreign to the memories and traditions of

my surroundings, growing up in various places did make me conscious of

peoples' behaviors and attitudes toward public spaces and private property, which I flnd emblernatic of society's economie and political values. The

re-search that led to the production of 17.TI+17.T2 > P-o6-o6g + 04-047-34

was original! y fueled by my recognition of my persona! perspectives toward my

surroundings, but it is also an exploration into the more universal aspects of

the perception of space and the effects of ti me and memory on attachments

to our habitats.

17 .TI+I7 .T2 > P-o6-o6g + 04-047-34 foc uses on a portion of land in

the middle of Montreal, surrounded by Outremont, Mile End and Parc Ex-tension neighborhoods, that is being developed from a former rail yard into a

future science campus and student residences of the Université de Montréal.

I became aware of the site a few years after the lot had already be en sold

by Canadian Pacifie to the Université de Montréal, but before the

construc-tion started, which in tu rn was already underway when I started the documen-tation that makes up the visual portion of this research.

time when there are still remnants ofwhat it once was, but just before we start saying "do y ou remem ber wh en ... ?" The space and its immediate surround-ings are on the verge of change, but are still within the grasp of memory; its previous character is still remembered by its former inhabitants and can still be experienced on the fringes of construction.

This site is one of many such transformations happening throughout Montreal and the world, each emblematic of the unique changes happen-ing in each of the neighborhoods that houses them. Aside from my personal familiat·ity with the former train yard, I also found it a f:ttting final project for an academie degree, not only because the site is symbolic of the socioeco-nomic shifts of the surrounding neighborhoods, but also because the deve l-opment juxtaposes the transient nature of university students and staff with the permanent community. Academie institutions gather a variety of people from different backgrounds under increasingly short-term projects and con

-tracts. The temporality of their positions often results in internal networks of interactions and a potential dissonance from the communities that foster them. The intrusion of the future university campus into already established neighborhoods will bring about cohabitation of people with severely different

attitudes to the space they occupy. This difference in commitment to a place has often be en at the base of my research and artistic practice.

OBJECTIVITY THROUGH ACCUMULATION

IN TEXT AND IMAGE

~""""'--''' ..

74]

---Photographs-and

quotatj_2n~=-~~f!l,__ because

they

are

taken to be

pieces

of

reality

,

more authentic than

ex-tended literary

narratives.

The

only prose that seems

credi-ble to

more and more readers

is

no~ th

~

fi~e

.

~riti~g

of

someone like Agee,

but the

raw

record~ditedor

unedit~dtalk into tape

recorders;

fragments or the integral texts of

sub-literary documents (court records, letters, diaries,

psy-chiatrie

case

histories, etc

.

); self-d

.

eprecatingly sl

?

ppy, often

paranoid first-per1on reportage

.

·

"" ..,

·"·

rr.

~··: .. ,,..,.,..,.,

~

1

/ '

__ _

Happenings: an art of radical iuxtaposilion 269

.

.

·_.,_ ~· ·- .... ... -~·~'\·t.·~ ,..., •.. ._.::,..,..--·~··' ........ ;j: .. ·~·- •l.\..:.,._

.

Fr

q_

m .tbe.

Jl§§

.

cm.plage

to the who

le

room or

"envi

ronment" i

s

only one further

stcp

.

,

nl~fi

n

a

step,

th

e

. Happening,

simp

l

y

puts peo_

ple

_iÏ'lt

o

th

è

-

~nviron-_

ment and

sets

it

in

motion.

·~--

-

_,._• .. • ·~ ... • .. • " ' > • • ~ •• <! l

.

Th

erc

is

a Surr

ca

li

st

tr

ad

iti

o

n in

ttheater,

in p::1inting, in poetry,

in

the

cine

ma, in mu

sic, and in

the

novel;

even

in

archit

ecture

• • • • • • ••••••••!!BIBl•

.

The Surrealist trad

it

iop

in

ail thcse arts

is

united

bythe idea of

destro

y

in

g

c~n

-

vcnti~naÎ

~

_$

,e

n

in

g

s;~

_

{

c

r

~â

ting

n

ew

meaning

s

or co

untc:

-

mcanin

gs

throu

gh

radi-cal~0'~!aposition(the "co

ll

age

prin

c

iple

").

·

1

\

1 -78 STORY TIMEa·

,

LliiCSIISld; F 1 1 '1 1 l!2

'· ' Il ' 2 '2 -w'q " cl tbétld Iiig

1 5F

,

s 3 3:::=::::::::::::::::::::

~~

B

s r

'

y a---llillill-....

""'·-illllll--illllli ...

t, . . . ~ . . . ~? 7 1 1b

'

'?

z

so

ssiu

the'huet'

5 1 1,,

·

e

t b fiswwtw Rœstisn Bisa

th;wst'ir

l

rn

'ggn

1:

"1911'1 31§2be

'7 · Il · 'fi ' ·g 'f' ?? toç?

;; 21a tu

SI !l:gt!ss ;:

I!it

3 1 5 F le·----IIIIMiililiM.

It no longer has the status of a document that does nol know what il says, cited (summoned and quoted) before and by the analysis thal knows it. On the contrary, it is a know-how-to-say ("savoir-dire") exactly adjustcd to its abject, and, as such, no longer the Other of knowledge; rather it is a variant of the discourse that knowsand an authority in what concerns thcory.l j j • • • • • • • l l l i l *

al

2 ;· ·hgd;;gl

hoœ

e

'

ssis;

2d

,

.

1-z

1s

1

2W2

in

1

:l'

h?Ji

!:ssr

·

'

2 'Il

3 1F:'

t '. '?nr

iiiStGI§

ICibTM

The Artist as Ecologist

•

•••••lillillllilliil•ilil

·

•

·

Ecology is defined as the totality or pattern of relations bet\vecn organisms and their cnvironment. Thus the act of creation for the new artist is not so much theinveQtion of new objects as the revelation of previously unrecog::-· nizcd relationships between existing phenomena, both physical and

metaphysical.

--~~~----·••••••••••••

Artists and scicntists rearrangc the erlVironmcnt to the advantage of society. Moreover, we find that ali the arts and sciences have moved alo-;·}g an evollTtTonary path whose milestones are Form,

"Structure, and Place. In fact, man's total development as a sentient o eing can be said to follow from initial concerns with Form or surface appearances, to an examination of the Structure of forms, and finally to a desire to comprehend the totality of relationships between f.orms, th at is, Places. il

ce

lt §dilCI Lill)t

s

tl gl 1 il. Œt'WSR ' el

.

i

1 ·~ 1• 0 Î W

Ftk

es

iiccp

liS;;

m

li15

p

ii!!qHs s

6 ?('Ph

E

on

1·

b

1q

•

l

a

fil:ul

Uanua!1

û

I

r·-~~'"'·""

r

t:

1

;

" !''. ~·

l

g

-ii ~:

~

~

~

"i~,lTh

e

D

eath of

the Author

. . . ~ . . . ~ . . ~--J

• • • • • wntmg is Jhe destruqtion __ qf_~y~ry __ yoi_ç_~,.-Qf every point_ of or.igin. Writing js_ thaLil_~u.tral, _composite, oblique space where our subject slip~ away, the negative

where ail iden.tity is !ost, starting with the very id~ntity of th~ body writing.

- - - -disconnection occurs, the voice !oses its origin,

the author enters into his own death, writing begins. The

sense of this phenomenon, however, has varied; in ethno-graphie societies the responsibility for a narrative is never assumed by a person but by a mediator, shaman or relator

whose 'performance' - the mastery of the narrative code

-may possibly be admired but ncver his 'geni_us'. ]'

mt

rr

n

&

·

1r

'

·

r

'

ssis

i

fe

m

f ;~;.

t.

!_~

,_,::.J.:~

146 1 IMAGE - MUSIC - TEXT

•!.,~, '... ' . ,, • .....,. • ...,..,_ ... , ...,"!>!•··~ ~~w.-.r&~~mw....:--.,i-..l!illM . . . . S.~.,Ll:LCJ'~U-U-1. .. ~~~

't~~1éŒdlatm:tl!it~

--~~-Having buried the Author, the modern scriptor can thus no longer

believe, as according to the pa the tic vicw of his predecessors,

that this hand is too slow for his thought or passion and that

consequently, making a law of neccssity, he must emphasiz.e

this delay and indefinitely 'polish' his form. For him, on

the contrary, the hand, eut off from any y~ic_c,_ bq_r_ne by.a

pure gesture of inscription (and not of expression), traces a

field without origin

e~•

~

..~

W[

fown

owtha

t

a text is nota

li ne of words releasinga single 'theological' meaning (the 'message' of the

Author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of

writings, none of them original, blend and clash. The text

is

a

tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerablè ..èe~tr

~s

~

·

of

~uÏt~r~.·

:

w

.

.

.

il

,·.· ,,

BI· .. ,.~,,,,.-,i-

l

·

..

·

.

··

•

•

... ~,·

·.·.--.-..

.

.

·

.. •

• • ••HV~..-1 ... "" •• .,{. • t-'Il • 1 '• • '< ,.\ 1 ~ .. : .. ~ · ."'~· · ·'-~~t· ... '"' ,vJ~r .. ,,-;~)··:v .. ~·~.v ~ .~~"f~~:~ ",.t~·'

.. t,V~1thf:•·l ''!' r. \,;;tq . .:(.1 ·.·.:<\$r.s1':'·~~4i;1/·.s ~'.t-~

the writer can only imitate a gesture that is always anterior,

never original. His only power is to mix writing~ •. to_c_o_unter

the ones with the others, in such a way as never to rest on.

any one of them. Did _hewish. to express himsez(, he_pught ..

i

V

!east to know that the inner 'thing' he thinks to 'translate'

is itself only a ready-formed diciionary, its V:,ords only

cxplainable through other words, and so on iridefi.riitely; ·

••• , 1.. '1\>. ,i_ ... ~ J!~ "'\.·' . A~~,..:'s:..:. ·· ... ;,.~ \~/).~: .. ·:; .. · .. · ·?.:: .

:.· ! r ,.-i~'J).'',.v,:1'l-.::~1•w:i.u.;~j~,!~·~!}H'i'-' _,: !\·~ l,.'t•·t~*•'.:)·i.~~il.,.. ~~.'.

~Wti~iGJMWMmMftiNiiJtfi'iM ~~Md*""'l

J

Sf~MltY~DliD .il..

l'

i-; •1[:

~

~

!'r:

f 'l

r

t

~;·

•

J'

'

$

Th us is revealed the tota

l

existence.

of writing:

a

text is made of multiple

writings,

drawn from many

cultÜres and entering

into

mutual

relations

of

dialogue,

parody, contestation, but there

is one

place

where JJ1is

multiplicity

is focused

and

that place

is

the reader, not,

as was

hitherto

said,

the

aut

h

or.

The reader is the space

on whicl),

ali the quotations

'

that

m

i

kë'

-

ûp

-

a

\Y

rlting are

inscr

i

b

-

~d

_

y.r

i

J_

h,

o

u

t

apy of them

being lçi

'

s

_

t.;

-

~ t

e~t'-

~

.

unity !!,

es

n

ô

'

t

·

-

;~

~

ü

'

~

o

_

rigin

,

but in. i_

t.s

,

destinatiQ!:l~

..

i!iiff::Jifï!,L ,'

s )

, ,

1

/

1

;

têf

•••11

we

know that to give

writing

its

future,

i

t is

necessary to

overthrow

the my th: the birth

o

f the reader

must be

at

the

cost of the death of the Au

thor.

READING AS POACHING 169

ii

JI

I!iéiiAPII

bill]

Yiiàpea

&il&sa:

•.:

n

TP J" 1

1

g

&ClA2611 IE&Gi!i§ &ilS:!

1 , . 27br'

nes

r 1 1s

sù

'

.

1l' ( 1 LilY Lb CCii CYQGI:S lb Il§

itEl'f!

-., t

tb

hd5::'

liih? ES WP 1 1 1 • T 1 JIa

.

5J

!ilS III&i::PSI&tSlJ Sig g

.

What has to be put in question is unfortunately not this division of la bor (it is only too real), but the assimilation of reading to passivity. ln fact, to read is to wander through an imposed system (that of the text.

analogous to the constructed order of a city or of a supermarket). Recent analyses show th at "cvery reading modifies its object. "8 that (as Borges

already pointed out) "one literature differs from another less by its text th an by the way in which it is readl "9 and th at a system of verbal or

iconic signs is a reservoir of forms to which the reader must give a meaning. If then "the book is a result (a construction) produced by the

reader,"10 one must consider the operation of the latter as a sort of

le

c

rio,

----

the _production proper to the----

"reader" ("lecteur")." The reade~ kes n;_i!~!:. the positiono

C

the· author nor an author's position:...tJ_ei:nve~~-~-~~-~t~me_thing ~ifferent from wh at they ~'intendeg." {-le detac~~E:!. from their (lost or accessory) origin. He combjnes t~jr Jrag_ments a11d cr~ates something un-known in the spac~ qrgani~ed by

their capacity for allowing an indefinite plurality of meanings.~ ..._

.

..

. ..

..

.

-

.

..

l 1~

1J

1

1

1

Il

Ill 1!!11

1!111

1!11~1!!1!!,111111

..

sdrs

I 11

2

1

2

23

Ç!GBL

bd 1

1•

li

1

.

.

,

p

2 Gbiliiii

1

;

1 1

g

1 1

p

1

1

.

t']SS

~.

•

111111!1

Ill

1111!1

Ill

1

11

1

1

Il

11

fi

..

1

'.

1 1 t t._.._

_1 • _._..

. '.

'

.

t1

Lb

Sté

IL&h21

Of

51!1152222

;113)

15

1 ')?a

;-:..

_1 .1.C.. • _1 ; . ·pli

1

IMISÇL&II Lj8151

1

65

t 1 t.

ai

t

cou'

d

t1

2 Jfi

"

-

I f I : , 51

9

IF

RI

.1..

..1 ..1 .L ..1fi

2--

-

agg agas

;

1

·ag

cs

GE

àtsscessJ

l

PP

il

al

a as;

men

1 IIi&§[

§[ddj

..

Cid

1

!@,

.

g

A)]

sb

1 1 1!'A

t.

,.

2 1s'

J a 25

5

1

6

2 j f._ 1.,

.

:,. -~.

.

L .L ; ~~il

...

Il

~&Il 21!!1.

un

m1~ ~~ ~~~~nen.

1!1

1

i&iiiil~

~hlill~&i

iii

i(!Ji

iii.

1

Il

siiii!IIIIIJ

Ill Mie I

.

IIIIUU

1!!11

li

lUi

prjag,

11

;

LLI§h

a

1

1

11

surs

?re

~UiiliUI ·~

g

1

1

1

1

'

•

•

1

i

IUiliiilli;l.

&jpg;lg

sds:'

tl&$1§

ecc;:cea

&ddt

li !dt

.

'

1rsmjçhs

er

..

1•

1

5

i

1

Îiill

1!1,

t

•

"

1

.-.

J

• SI?ES

.

i

1

••

1

., 11

6

d

1

1

Gestalt theory believes it has discovered a decisive aspect

i

n

r

ecogn

izi

ng

t

he ex

i

stence of phe

n

ome

n

a a

n

d co

n

te

x

t o

f a

different-of a formall

y

diffe

r

en

t

-

n

at

ur

e

.

And this

n

ot

merely

I l lthe humanities

.

The basic

th~sisof gestalt tb eor v

might be formulated thus: There are contexts in which wbat is

~

lï~

p_pening

in the whole cannot be deduced from the

charac-teristics of the separate :eieces, but converselyj what

ha:r;u~ens~to

a

eart of the whole isl in clear-cyt cases

:t_

dete

r

mined by the

l

aws of the 1nner structure of

its

whole.

_ .::;_

..

n...

1

1

1

,

1

1111!!111

~'

hui

llllil

}r

fi"'*

1.

2

&3222321& 3

9

p

2

•

gts

a tic

&Gl&Zl&

•~'

rtss ps

1

s&hm

t;

JtHM

a

.

,

'

ï

1I l l

1

l!i

l

l

,(~1

·

i

li

1

1

1

;

1 1

Copyright (c)

2000

Bell &

Howell

Info

r

mation

and

Learning Company

Copyright

(c) New

Schoo

l

of Social Research

1 2

;OBJECTIVITY THROUGH ACCUMULATION IN TEXT AND IMAGE

If the pUt·pose of written mémoire is to supplement the artwork and to situa te it in the larger context not only of art history, but also history in

gen-eral, I fmd the best way to do this is not by claiming persona! originality, but

rather by recognizing the shared nature of knowledge. By physically

structur-ing my written research as a literary scrapbook of voices gathered from

dif-ferent theoretical backgrounds including; geography, anthropology, socio

l-ogy, urbanism, photography, and film theory, among others; I aim to bring together a number of disciplines that are the basis for my practice. This text is an accumulation ofwriting by scholars who devoted their lives to the study of the nu merous disciplines that guide my work today.

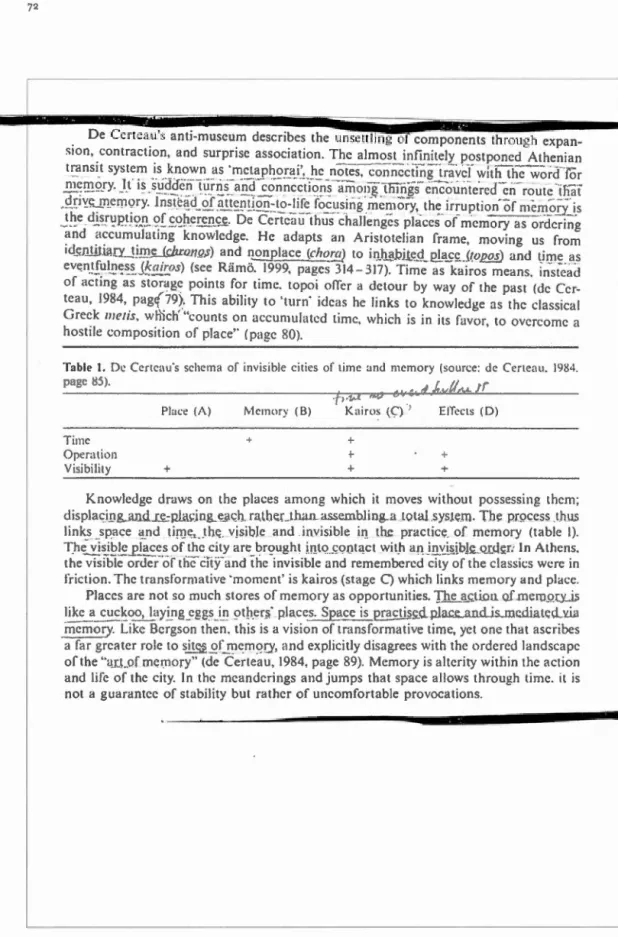

Although accumulation has always been a part of my visual work pro-cess-either through painterly collage or multi-projection slide installa-tions-this is my nrst attempt to translate collecting into a writing strategy. This concept took shape as I became conscious of the number of citations, footnotes, paraphrases, and changes in the authors' voices within various aca-demie and theoretical texts. I became progressively frustrated by the constant interruptions to look up the original sources and found myself incapable of finishing one book or article without reading the cited original, then looking up the citations in the cited text, and so on and so on. For me, contemporary academie writing became reminiscent of a continuous game of broken tele-phone.

Recognizing the role of the author (or artist, or scientist) as a

col-lector and interpreter of pre-existing information allowed me to resolve my

frustrations with the conventional structure of academie writing, and to ap-proach the text according to the same logic I often apply in my visual prac-tice. ln part, influenced by the theories of Gestalt psychology as outlined by

Max Wertheimer'-stipulating the ability to derive new totalities from patterns

of information-! aim to examine written knowledge and visual perception

through the accumulation of individual components, be it images, texts, ob-jects, or thoughts.

As is evident by this point, this mémoire is a compilation of photo co pied books and articles re ad prior and d uri ng the maitrise en arts visuels et mediathiques. By including the original texts, I acknowledge the voices of my theoretic pre-decessors with minimal interpretive distortion. For the sake of coherence and

continuity, the information not entirely pertinent to the parameters of this

research has been redacted, although I still include handwritten notes and markings as evidence of my personalline of thought.

Additionally, the collaged structure of the text references the process

of reading as the means of accumulating information. While working within

the restrictions of academie text requirements, the layout of this mémoire is

de-signed to mimic a traditionallayout of a book. The borders around the pages,

the classical typeface (Mrs Eaves I'2/I8pt), li ne length, leading as well as the double-sided prin ting are meant to further allude to reading as source of ac-quired knowledge.

The resulting text aims for objectivity though a multitude of sources rather than privileging one voice of the individual author. Furthermore, it demands active engagement from the reader/viewer. ln addition to the con-ceptual logic behind scrapbooking as academie writing, this mémoire is also a physical compilation of reference material for anyone interested in topics of

spatial perception or the photographie means of its documentation.