Schoolyard Agency

Childhood, mobility, and cultural reproduction amongst mobile

families.

Thèse

Gabriel Asselin

Doctorat en Anthropologie

Philosophiae Doctor (Ph.D.)

Québec, Canada

© Gabriel Asselin, 2014

iii

Résumé

L‘expérience que les enfants font de leur communauté est le résultat de l‘interaction de plusieurs facteurs. Parmi ceux-ci, l‘agencéité des enfants est identifiée comme étant d‘une grande importance, malgré les contraintes imposées par des facteurs externes tels les structures organisationnelles et institutionnelles ou la participation au sein de registres sémiotiques. En utilisant le cas présenté par les familles militaires francophones de Cold Lake, en Alberta, cette dissertation contribue à tracer le portrait d‘enfants qui jouent un rôle d‘importance dans l‘expérience de la vie communautaire ainsi que dans les processus de formation identitaire au niveau de la communauté.

La vie sociale des jeunes francophones de Cold Lake est caractérisée par un haut niveau de mobilité et est assujettie à des registres sémiotiques persistants au travers de discours couvrant des sujets tels la mobilité, le militaire, et l‘identité francophone. Le travail ethnographique accompli à Cold Lake permet de décrire une communauté où se rencontrent des individus ayant vécu leur mobilité familiale dans des contextes différents et de documenter les effets de cette diversité sur l‘expérience communautaire des enfants ainsi que sur leur concept d‘identité et d‘appartenance.

Cette réflexion est fondée sur un travail the terrain ethnographique autour de la communauté associée à la base de la 4ième Escadre de Cold Lake, une base de l‘Aviation royale canadienne. En

étudiant une communauté caractérisée par la mobilité de ses membres, je fais la démonstration que la continuité au niveau communautaire, ainsi que la reproduction culturelle, n‘est pas nécessairement liée à une continuité au sein de la population. Ce faisant, je présente la communauté comme résultant de l‘expérience d‘environnements sociaux par le biais d‘une l‘agencéité entrant en contact avec des registres sémiotiques au sein de structures institutionnelles.

Finalement, cette dissertation fait aussi la description des défis et des opportunités que rencontrent les familles militaires francophones de Cold Lake. Leur situation particulière, en tant qu‘individus mobiles vivant en marge de plusieurs institutions et organisations, nous permet d‘affiner la compréhension des impacts de la mobilité et des conflits de loyauté sur les concepts d‘appartenance et d‘identité.

v

Abstract

In this dissertation, I show that while the experience that children have of their community is influenced by external factors such as semiotic registers and structural relationships, it is also shaped through their own agency. Through working with children of French-speaking military families in Cold Lake, Alberta, I contribute to a portrayal of children as playing an important role, not only in how they experience community, but in the very shaping of the community itself.

Through a focus on how children of military members attending the French school École Voyageur experience their social environment, it becomes apparent that while this is characterized by a high degree of mobility, they are nevertheless subjected to lasting semiotic registers defined by ongoing discourses surrounding topics such as mobility, the military, and francophone identity. By taking account of how children of mobile families, and adults involved in their lives, express their understanding of their place within various institutions, this dissertation contributes to furthering the understanding of potential effects of various patterns of mobility on childhood experiences of community and concepts of identity and belonging.

This work is grounded in data collected during fieldwork in and around a military community associated with 4 Wing Cold Lake, a Royal Canadian Air Force base. What is shown with the data gathered from fieldwork is that continuity in a community, and even cultural maintenance, does not require continuity within the population. In doing so I show that conflicting views concerning the idea of community can be reconciled by describing it as the result of experience of social environments through the encounter of individual agency with semiotic registers and networks of institutional structures.

Finally, this work also describes some of the challenges and opportunities encountered by children of French-speaking military families in Cold Lake. Their particular situation, as mobile individuals evolving on the margin of multiple institutions and organisations, makes them subjects of interest to understand the impacts of mobility and of diverging loyalties on concepts of belonging and identity.

vii

Table of Content

Résumé ... iii

Abstract ... v

Table of Content ... vii

List of Tables ... ix List of Figures ... xi Acknowledgments ... xiii Chapter 1 Introduction ... 1 1.1 Research Context ... 1 1.2 Research Questions ... 4

1.3 Children and Community... 5

1.4 The military and Community ... 8

1.5 Research Contributions ... 10

1.6 Thesis Breakdown ... 12

Chapter 2 Theoretical Background ... 15

2.1 Introduction ... 15

2.2 An Anthropology of the Military ... 17

2.2.1 Military culture ... 17

2.2.2 Institutional Demands ... 20

2.2.3 Military families ... 21

2.3 The Anthropology of Childhood ... 22

2.3.1 Child-centered anthropology ... 23

2.3.2 Childhood and Adolescence ... 26

2.3.3 Children and the community ... 29

2.4 Mobility ... 31

2.4.1 Transnational studies ... 31

2.4.2 Children of mobility and transnational families ... 32

2.4.3 Military brats ... 36 2.5 Theoretical Concepts ... 37 2.5.1 Agency ... 38 2.5.2 Community ... 40 2.5.3 Discourse ... 43 2.5.4 Semiotic Registers ... 44 2.6 Conclusion ... 46 Chapter 3 Methods ... 49 3.1 Introduction ... 49 3.2 Methodology ... 51 3.2.1 Data collection ... 51

3.2.2 Data treatment and analysis ... 59

3.2.3 Ethical Concerns ... 60

viii

3.4 Research Focus ... 67

3.4.1 Cold Lake ... 69

3.4.2 Schools and the Canadian Forces ... 76

3.5 Conclusion ... 80

Chapter 4 Structures: ethics and bureaucracy when researching the Canadian Forces ... 83

4.1 Introduction ... 83

4.2 A Bureaucratic Fieldwork ... 84

4.3 Ethical Concerns ... 87

4.4 The Approval Process ... 89

4.4.1 First contacts ... 90

4.4.2 First field season ... 92

4.4.3 Second field season ... 96

4.5 Elements of the Structural Framework ... 98

4.5.1 Gatekeepers ... 98

4.5.2 Control ... 100

4.5.3 Respect of ethical principles ... 103

4.6 Conclusion ... 103

Chapter 5 Agency: children and the construction of social structures ... 109

5.1 Introduction ... 109

5.2 École Voyageur ... 111

5.3 Military families ... 122

5.3.1 The roots of mobility ... 123

5.3.2 Having military parents ... 125

5.4 Life on the Base ... 128

5.4.1 Military families and the Canadian Forces: ... 136

5.5 Conclusion ... 139

Chapter 6 Semiotic Registers: patterns of mobility amongst military brats and oil-patch kids. ... 143

6.1 Introduction ... 143

6.2 Patterns of Mobility ... 145

6.3 Families on the Move: Military Brats ... 150

6.4 Families on the Move: Oil-Patch Kids ... 156

6.5 Intersecting Trajectories: Mobility at École Voyageur ... 159

6.6 Conclusion ... 166

Chapter 7 Meeting Ground ... 173

7.1 Introduction ... 173

7.2 Encountering Institutional Structures ... 174

7.2.1 The military from a management perspective ... 176

7.2.2 Communicative competence within institutional structures ... 179

7.2.3 Overlaps of institutional structures ... 180

7.3 Encountering Networks of Meaning ... 182

7.3.1 Lifestyle encounters ... 183

7.3.2 Cohesion and isolation ... 187

7.3.3 A community based on mobility ... 188

ix

7.4.1 The play ... 191

7.4.2 The Youth Centre ... 193

7.4.3 Choices in education ... 195

7.5 Conclusion ... 199

Chapter 8 Conclusion ... 201

8.1 Introduction ... 201

8.2 Contributions to Anthropological Perspectives ... 203

8.2.1On civil-military relations ... 204

8.2.2 On patterns of mobility ... 205

8.2.3 On the concept of community ... 207

8.3 Applied Perspectives ... 208

8.3.1 On children of military families at École Voyageur ... 209

8.3.2 On francophones and the 4 Wing Military Family Resource Centre ... 211

8.4 Perspectives on Future Research ... 212

Bibliography ... 215

Appendix I – Participant consent forms ... 223

Appendix II – Interview participants ... 229

Appendix III – Research approval submission forms with the Social Science Research Review Board ... 231

ix

List of Tables

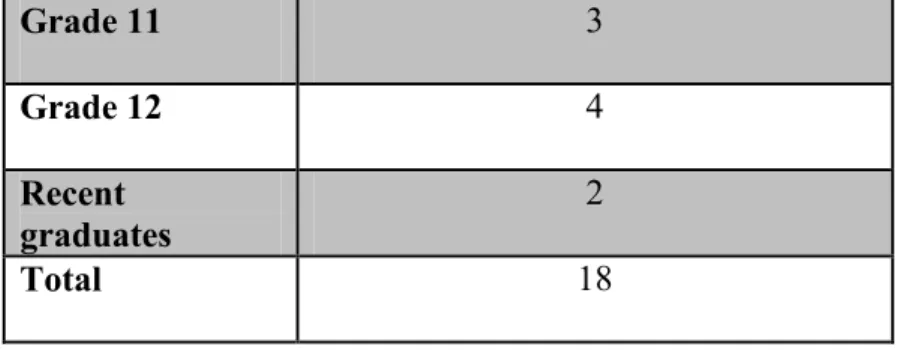

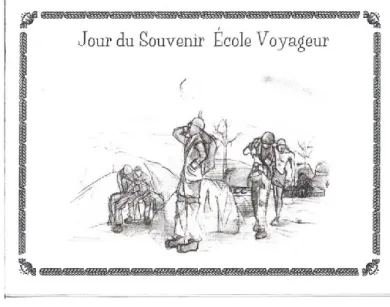

Table 2 - Youth Participants ... 58 Table 2 - Albertan communities with more than 400 first official language French speakers.

xi

List of Figures

Figure 1- Welcome sign at CFB Cold Lake ... 66

Figure 2 - Map 1 - Northen Alberta oil triangle (map from Natural Resources Canada, triangle added by author) ... 71

Figure 3 - École Voyageur vehicle logo (photo by author) ... 74

Figure 4 - Map 2 - Northeast Alberta, with the following locations identified : (A) Cold Lake; (B) Bonnyville; (C) St-Paul; (D) Plamondon (source Google Maps) ... 80

Figure 5 – École Voyageur (photo by author) ... 111

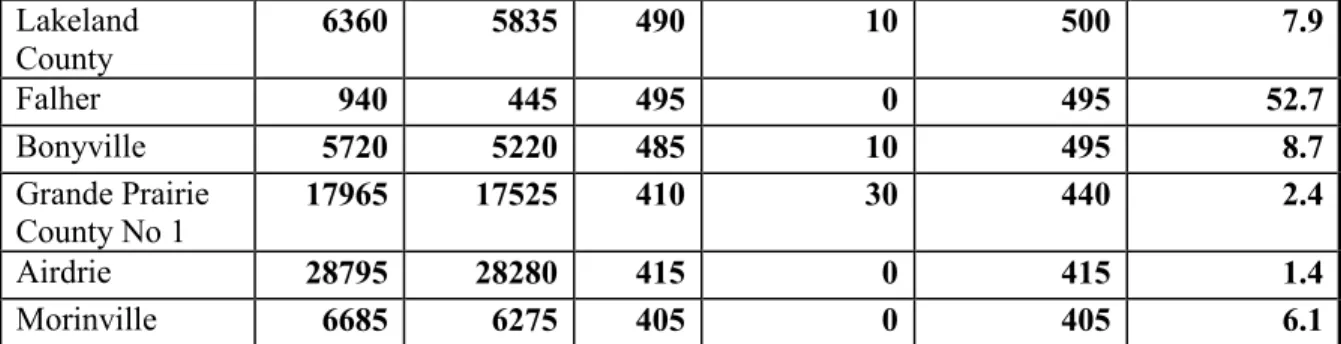

Figure 6 - Commemorative plaque at École Voyageur (photo by author) ... 113

Figure 7 – Project on careers and values at École Voyageur (photo by author) ... 117

Figure 8 – Sign posted in from of the Art Smith Aviation Academy (photo by author) .... 119

Figure 9 - Cover of program for 2010 Remembrance Day Ceremony at École Voyageur 121 Figure 10 – Airplane on display at a Cold Lake major intersection (photo by author) ... 129

Figure 11 - Business catering to military members in Cold Lake (photo by author) ... 131

Figure 12 - Hallmark greeting card no. 1 ... 132

Figure 13 - Hallmark greeting card no. 3 ... 132

Figure 14 - Hallmark greeting card no. 2 ... 133

xiii

Acknowledgments

The completion of this dissertation was made possible by contributions from many groups and individuals. While a complete list would be quite lengthy, here are some of those for whom I am particularly grateful.

First and foremost, I would like to thank the staff, students, and families of École Voyageur, who welcomed me in their houses, halls, and classrooms during my fieldwork, providing both the data and motivation which constitute the core of this thesis. I hope that the words they find in these pages remain true to what they have shared with me during the eight months I spent in Cold Lake. I would also like to thank the school administration for accepting to be part of this research project as well as for their ongoing technical support while I was in the field.

I would like to acknowledge the 4 Wing Military Family Resource Center and CFB Cold Lake for their willingness to participate in this project and to sponsor the approval of my research with the Canadian Forces. Here, I am also especially grateful to the members of military and oil-industry families who took the time to share stories about their life in Cold Lake and in other communities.

I would like to acknowledge the contributions from the funders who made this research possible: the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the Association des

universités de la francophonie canadienne, the University of Alberta, and Université Laval.

Having transferred institutions during my PhD program, I find it important to thank those at the University of Alberta who helped me in setting up my project, in particular the faculty members who sat on my supervisory committee and the administrative staff at the Department of Anthropology. At the Université Laval, I would like to thank everyone who helped with my transition there as well as the members of my examination committee whose insights were very valuable.

xiv

In both institutions, I would like to give special thanks to my graduate supervisor, Michelle Daveluy, whose continuous support and critical eye throughout my entire graduate student career were instrumental in shaping this thesis.

On a personal level, I also would like to thank the help and support of many friends and family members who encouraged me in numerous ways to complete this research project and thesis. Be it through moral support, editing, professional advice or child care, these individuals helped me in their own ways at various stages of my graduate program.

My understandings of the nature of community and family have of course been shaped by my own personal trajectory. I would therefore like to thank my parents, Jocelyne Bertrand and François Asselin, for instilling in me the curiosity in human nature which led me to pursue my graduate studies.

Finally, I would like to give my most grateful thanks to my wife and ever-present research partner, Jodie Asselin, who accompanied me throughout this entire process. Her competent support as reviewer, consultant, editor, to mention only of a few of the roles she played, warrant her more credit towards the completion of this thesis than I can possibly give her here. In fact, having travelled with her and our children to multiple fieldwork locations and having relocated various times for work reasons as academics, I cannot escape the fact that something else I have to thank for the motivation in completing this thesis is the support and sacrifices made by our very own mobile family.

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

“Children aren’t coloring books, You don’t get to fill them with your favorite colors.”

Khaled Hosseini 2004 – The Kite Runner

1.1 Research Context

In 2008, I wrote a commentary in Anthropology News where I explained how I felt that being a parent provided grounding for my academic work (Asselin 2008). As a researcher interested in notions of community, language socialisation and cultural reproduction, having children of my own provided new and personal perspectives on issues I had previously approached from largely theoretical standpoints. One realisation that came from this was the extent to which my children were moulding, not only my identity, but my perspective on the world and the framework I used to evaluate and motivate activities. I progressively got acquainted and started using services I had never interacted with before, or had little knowledge about, changed the ways in which I travelled around the city I lived in and adapted the rhythm of my days to new priorities. I also started relating to people differently as my lifestyle and outlooks were changed by the necessities, and experience, of parenting. Slowly but surely, my children and my relationship with them were changing the way I was experiencing community.

2

This should not be a surprising statement for anyone who has had experience with parenthood, but remains important for me as it marks a change of focus in my research. Surely, if children can have such an impact on how individuals experience their lives and social environments, their role as agents in processes that define group and cultural identity must also be of importance. While children had always been present in my research, they were often in the background, a factor to be taken into account in how their parents interacted within social networks, but not as primary sources of cultural production and reproduction. Indeed, many anthropologists have pointed this out as a generalised problem in literature pertaining to the anthropology of childhood (e.g. Montgomery 2009, Hardman 2001, Hirschfeld 2002).

This is in part what motivated the research project from which this dissertation draws its data. Where my previous work (Asselin 2007) has looked on parents as the main focus in understanding how members of French-speaking military families experience their community, I shifted my attention to the children of such families.

In 2009 and 2010, I conducted fieldwork in the City of Cold Lake, Alberta, in order to study how children of military families relate and experience their community. In continuity with a previous research project, I focused on a specific sub-group of the Canadian military, that of French-speaking families. My main research partner was a kindergarten to grade 12 (K-12) French school, École Voyageur (http://www.centreest.ca/voyageur), that provides services to many military families. While the project originally aimed at studying the socialisation of children raised in military families, I quickly reoriented my theoretical approach to document not only how children were being socialised, but also how they themselves contributed to their community and group identity, as well as to processes of cultural production.

Over the course of this research project, as I oriented my focus on issues of mobility, I found not only that children of mobile families have their own experience of community that differed from that of their parents, but that they actively contributed to shaping semiotic registers on mobility itself. Also apparent was the fact that the normality of

3 mobility in a school that caters to highly mobile families can be both beneficial and detrimental in fostering practices which would minimize the challenges of such lifestyles. Mobility is only one of the elements imposed upon the families of military members. For the sake of operational efficiency, they are required to share one of their own with an institution which tolerates very little divided loyalties from its members. In a way, the clause of unlimited liability to which military members have to agree, according to which any sacrifice can be required of them in the line of duty, is extended to their families that must also accept that the needs of the military will often take precedence over theirs. Children of military members must also face this. Some of the challenges with which are faced children of Canadian military families are adroitly portrayed by Claire Corriveau (2010) in her recent documentary portraying the lives of a number of military families living near the Petawawa army base in Ontario. While there differences between the reality of military families from different bases, and in particular from different branches of the military, I found that the context described in Corriveau‘s documentary corresponded on many points to the one I found in Cold Lake. Children of military members may have to go for weeks, even months without one of their parents, who may miss important moments in their lives. Older children may have to step up and shoulder some additional responsibilities while their military parent is away. Through this, they continue going to school, bringing in this public environment the burden of private matters. In a school that caters to many military families, children are often aware that their situation is not unique. But children of military families are not simple victims of circumstances; their actions and interactions influence their social environments, not only for them but for the entire community.

Through this dissertation, I show that while the experience that children have of their community is influenced by external factors such as semiotic registers and structural relationships, it is nevertheless also shaped through their own agency. The example provided by children of French-speaking military families in Cold Lake contributes to an understanding of children as playing an important role, not only in how they experience community, but in the very shaping of the community itself.

4

1.2 Research Questions

The main research question leading my enquiry was the following: How do children of French-speaking military families in Cold Lake experience their community? This meant documenting how they felt about issues such as the military, their mobile lifestyle, their school, and their linguistic identity. This initial interest gave rise to a number of secondary questions. Most important among these were: What roles do children and youth play in defining community experience, what is their role in processes of cultural production and reproduction, and what are the main factors influencing their experience of community? Among these questions is a thread that constitutes the core of this dissertation; a query into the nature of community. This enquiry concerns an apparent contradiction between conceptions of community as an abstraction with the actual experience of social environments that take place from an individual perspective.

Therefore, in this dissertation, I suggest a conception of community experience and community identity as shaped by individual agency encountering systems of structural relationships along with networks of meaning. This approach makes it possible to view communities as entities while acknowledging their fluxing nature and the fact that they are made up of a multiplicity of constantly changing individuals who are each experiencing their social environments in their own way.

Throughout this dissertation I use examples drawn from fieldwork to address the various components of this understanding of community experience. In chapter 4, ―Structures‖, I use my experience navigating the Canadian Forces‘ bureaucracy as an example of how institutional structures provide frameworks for community experience while chapter 5 focuses on agency, where I discuss life in Cold Lake from the perspective of children belonging to French-speaking military families. In the following chapter, ―Semiotic Registers‖, I discuss the patterns of mobility of military and oil-industry families in Cold Lake to show how individuals experience their community in part as interactions within

networks of meaning. Together, these chapters provide a foundation, from which we can

5 examine the idea of community itself. Each chapter emphasises the lived experience of community from the children‘s perspective, as subjects of various influence as well as agents in and of themselves.

École Voyageur and Cold Lake constitute a particularly fertile source from which to draw examples of this understanding of community experience. This is the result of the overlapping of elements within its population giving it unique characteristics, which will be outlined in the following chapters. These features of the research population allow for analysis in regards to communities which are characterized by occupations, age, language use, and mobility.

1.3 Children and Community

Rather than looking at children as mere components or subaltern group of an adult society, this research considers them as main agents of community building and cultural production. My interest in childhood and the family is twofold: 1) the family as foci of socialisation and language and culture transmission and 2) for the experience of community from children‘s perspectives. Morrow and Richards (1996) point out that most social research concerning children is looking at childhood as a developmental process and is interested in children mostly as ―future adults‖. The focus is therefore on who the child will become, through an analysis of various influences. While this facet of childhood is part of this research through the focus of the reproduction of culture, I mostly document how children are experiencing their community in the here and now.

Robert LeVine‘s 2007 article entitled Ethnographic Studies of Childhood: A Historical

Overview, provides a thorough account of anthropological interest in children. His focus on

―ethnographies of infancy and childhood in domestic and community settings‖ (LeVine 2007, 247) narrows his observation considerably since he openly omits school studies, theoretical works, studies of immigrant children, chronically ill or disabled children, research on child abuse, cultural politics of childhood, and archaeology of childhood.

6

LeVine presents ethnography as an essential contribution which anthropology can provide to improve the understanding of childhood.

―The ethnography of childhood, then, is based on the premise—constantly reexamined in empirical research—that the conditions and shape of childhood tend to vary in central tendency from one population to another, are sensitive to population-specific contexts, and are not comprehensible without detailed knowledge of the socially and culturally organized contexts that give them meaning.‖

(LeVine 2007, 247)

LeVine attributes a large part of the early anthropological work on children as reaction to other disciplines‘ search for universal concepts, mostly to psychology. Margaret Mead and Bronislaw Malinowski‘s works were at least in part such reactions, to the claims of Stanley Hall and Sigmund Freud, respectively. The relationship between anthropologists and psychologists is a complex one since while anthropology focusing on child development is always tainted by the psychology of the day, anthropologists ceaselessly endeavour to provide cultural critiques to find counter arguments to these same prevalent developmental theories. LeVine points out that to a great extent, psychology at large seems unconcerned with this problem, since most studies on childhood and development are conducted in the United States and other developed countries even if 88% of the world‘s primary school children live in ‗less developed regions‘ (LeVine 2007, 250).

LeVine claims that the extent of ethnographic work on children is still largely inadequate and that a documentation of the wide array of contexts in which children live is necessary to a better understanding of childhood. Such documentation would be precursor to cross-cultural comparison and theory building. Hardman (2001, 504) also expresses this view by stating that her interests lie in a synchronic understanding of children‘s lives rather than in the usual diachronic approach looking at children as future adults.

This dissertation provides an ethnographic portrait of life in a military community, focusing on elements which are of importance for children. In the following pages, while I discuss elements which are not directly connected to children‘s lives in Cold Lake, or that are related through adult perspectives of life in the community, these are shown to consistently

7 go back to children, be it their experiences or their impact on social networks and semiotic registers. While this dissertation may not present what would be considered a child-centered anthropology, it definitely finds childhood as a focus of its concerns. In a recent article on the various uses of communities of practice, Bonnie McElhinny (2012) outlines some of this concept‘s contributions to the field of materialist-feminist anthropology. Among other, she points out that the emphasis on the learning element involved in communities of practice make it particularly useful in a perspective which looks at categories of identity such as gender as ―something one continually does‖ in opposition to ―something one has‖ (McElhinny 2012). I believe that similar thinking can be applied to our understanding of childhood. By showing that children understand their own place and identity through their active participation in social networks, semiotic registers, and as operating within certain institutional structures, we can present childhood not only as a stage of life defined by biological age, but as a component of the self which is in constant fluctuation. Maybe being a child is more the result of activity (something one does) rather than a state of being (something one is).

Worthy of mention is that throughout this dissertation, I use the terms child and children broadly, in relations to school-age individuals from kindergarten to grade 12. As such, it includes many who could also be otherwise described as youths rather than children. However a number of factors contribute to my decision to mostly use the term children. Foremost among these is the fact that the individuals in whose perspectives I focus on in the context of this research are of interest not because they are young but because of their belonging to family units within which they are children. A focus on youths could be warranted, but I find that it would divert from my purpose of examining the community experience of individuals defined primarily as children of military families. This leads to a second reason for this choice, which is that the offspring of military members, which constitute the core of my research population, are generally referred to not as military youth or young members of military families, but as either military kids, children of military

8

families, or children of military (aside from the also common military brats)1. While many of the individuals I interviewed during fieldwork may more easily self-identify as jeunes (youths), rather than as enfants (children), they all relate to the label of children in the context of discussing their families. Therefore, using the term children allows referring to the entirety of my research population among the students of École Voyageur. The relative age differences of the individuals, and their impacts, is acknowledged and addressed when relevant throughout the dissertation.

1.4 The military and Community

Working with the military and with what some call military culture (Académie Canadienne de la Défense 2003, English 2004, Winslow 1997) provides an opportunity to better understand children of Canadian military families and the role of children as agents in community making. In her book discussing American military families, Mary Edward Wertsch (1991) claims that ―it [the military] exercises such a powerful shaping influence on its children that for the rest of our lives we continue to bear its stamp‖. Similarly, Ender (2002) has looked at the impact of mobility on such families. In line with such enquiries, this research explores the relationship between children, community, and the military in Canada.

More specifically, this project focuses primarily on French-speaking military families living in English-speaking localities. While French-Canadians have always been involved in Canadian military institutions, civil-military relations have generally been very different between English and French speakers (Bernier and Pariseau 1991, 1987). Bernier and Pariseau explain this in part as a result of the historical process which lead to the 1867 British North America Act, and the subsequent creation of a permanent armed forces in Canada. Up until 1920, when the 22nd Regiment was created, the only Canadian military units operating primarily in French were militias, and French-speakers had to wait until the

1 In French, common appellations include enfants de soldats, enfants de militaires and enfants de familles

9 1950s for the creation of other French-speaking environments in the Canadian military. Even then, it is only the adoption of the Official Languages act in 1969 which started a systematic creation of French language units in the Canadian Forces.

Furthermore, military operations have traditionally received significantly less support in Quebec than in the rest of Canada. Some, such as Granatstein (2004), claim that the Canadian Forces‘ focus on peacekeeping missions had as one of its objectives the promotion of a positive federal government image amongst civilians, particularly with Quebecers. French-speaking military families thus have to negotiate various perceptions of the military world, and children of such families are socialised to many discourses, including that of the military community, of the French-speaking minority, and of their parents‘ views towards these. Furthermore, they must also face both the way francophones are perceived in the military community and the vision that civilians have of the military institution.

Prior to the adoption of bilingualism programs, the historical dominance of English in the Canadian military, joined with the fact that many elements of the Canadian Forces are deeply rooted in British military tradition, shaped a work environment where being French-speaker could be seen as a liability. In discussing her research with the Canadian Navy, Daveluy (2008) pointed out that many individuals had to make difficult choices in regard to their linguistic identity as a result of their work. Some of these choices were individual but others were made by parents on behalf of their family unit and had lasting consequences for their children. For example, Daveluy spoke of a military member interviewed as part of her research onboard a Canadian Navy ship, who expressed a clear memory of the day when his parents gathered the family to inform the children of their decision to stop using French and start using English.

Through the case study provided by children of military families at l‘École Voyageur in Cold Lake, this dissertation provides a contribution to various fields of inquiry concerned with furthering the understanding of the ways childhood is experienced. For example, being the child of a military member differs from that of others because the parent‘s loyalty and

10

energies are appropriated by an institution that goes so far as to request unlimited liability. Having a parent whose responsibility it is to potentially sacrifice their lives in the line of duty puts a certain amount of pressure on their children. Many of the children encountered during fieldwork expressed being very conscious of the risks involved in their parents‘ occupation.

1.5 Research Contributions

By providing an example of how agency, structures, and meaning, interact to shape the nature of a community and individual experience, this dissertation contributes to anthropological knowledge at the theoretical, methodological, and empirical levels. At the theoretical level, the data collected about the children of École Voyageur illustrate the capacity of children to influence social environments and inform my conclusion that we adopt flexible interpretation of the concept of agency. I argue in these pages that some of the trends in defining agency are not adequate in taking into account more passive forms of action. Related to this idea is the importance of the dialogic relationship between children and the semiotic registers which they encounter and partake in. Once discourse is considered as social action which is constitutive of social structures, children`s participation in these processes must be taken as form of agency even if their intentionality is not always clearly articulated.

Another important theoretical contribution is in relation to the lasting debates surrounding the nature of community. In focusing on an environment mostly populated by mobile individuals but which still maintains continuity in its structures and identity, I propose not that the nature of community rests in localities, institutional structures, or networks of meaning, but at the interface of all of these as they are encountered by individual agency. This dissertation therefore contributes to a discussion on the impact of mobility on children, their notion of identity and belonging, and their relation to community. For a large part of the student population at École Voyageur, mobility is a fact of life which cannot be avoided and is incorporated to individual and collective identity.

11 At the methodological level, a central contribution of this dissertation is found in the discussion of the research approval process in chapter 4. Through it, I make a case for considering ethical and methodological approval process by third parties as a distinct part of fieldwork and data collection rather than as peripheral activities. I suggest the notion of bureaucratic fieldwork as a way to express this perspective, and argue that anthropologists deliberately expand their fieldwork methodologies into the preliminary phases of their research in order to gain a fuller perspective of the forces that influence their participant‘s lives.

Finally, this dissertation contributes to empirical anthropological knowledge in multiple ways. First, it draws the portrait of a population which is uniquely positioned at a crossroads between multiple communities. The children of École Voyageur are solicited for participation in multiple local groups: the Franco-Albertan community, the military community, and the wider Cold Lake community, as well as whatever community of belonging that their parents associate with. This allows for documenting the processes and experiences which take place in such a situation. Given the increasingly connected nature of global society, exploring the impact of multiple communities of belonging among children is an important step towards understanding this growing connectively more generally.

Secondly, this dissertation provides important details on the manners in which children of mobile families express their experience of community. Through this is presented comparative descriptions of community experience by both military and oil industry families. Finally, a thread which is apparent in the following chapters is the similarity between individuals experiencing mobile lifestyle in Canada and those of other mobile groups such as transnational families and Third-Culture Kids. The impact of movements of families within a country can be minimalized to the detriment of those they affect. For example, while participating in local communities of practice surrounded around their school, they also maintain connections with other parts of the country which extend their sense of belonging beyond their immediate social environment.

12

1.6 Thesis Breakdown

In chapter 2, I lay the foundation for the remainder of this dissertation by providing its theoretical background. In order to situate the research, the chapter begins by a brief literature review in key anthropological fields. These include the anthropology of the military, the anthropology of childhood, and anthropological studies on mobility. Looking primarily at the military as it relates to community and civil-military relations through the military family, the review of anthropological interest on the military focuses on the concept of military culture as well on the interaction between family and military institutions. Within the exploration of the anthropology of childhood, I begin by discussing previous calls for what has been labelled a child-centered anthropology. I discuss some key notions related to children in an anthropological perspective, including the relationship between youth and community. Finally, I focus the overview of the study on mobility in looking more specifically at work dealing with family mobility. In the last part of chapter 2, I discuss some theoretical concepts in order to define their use within this dissertation. First among these is that of agency, which is at the core of the thesis. Secondly, I discuss the concept of community, which has seen a wide number of definitions. I address a few of the more common ways in which community is defined, before settling on definitions that are grounded in interactions, such as the community of practice. Thirdly, as I look at community life as participation within networks of meaning, I consider the notion of

discourse. This is linked with the third concept which is discussed, that of semiotic registers, which constitute a basis for the way processes of cultural production and

reproduction are articulated within this dissertation.

Following the definition of theoretical concepts, chapter 3 lays out the more concrete aspects of the research project. I begin by providing a description of the fieldwork site, which is the City of Cold Lake, Alberta. I explain the historical background of the town, along with its connection to French-speaking populations, the Canadian military, and the oil-extraction industry. Afterwards, focusing more closely on my research population, I explain the historical connections between the military base of 4 Wing Cold Lake and École Voyageur. In the second part of chapter 3, I focus on methodology and ethical

13 concerns. As this research project involved both working with children and a military institution, a number of research approvals were necessary to alleviate ethical concerns. As chapter 4 describes in more detail the approval process with the Canadian Forces, in this section I mostly concentrate on issues relating on research on children and on conducting fieldwork in a school. In the rest of the chapter, I provide details on data collection and analysis methods which were used during and after fieldwork. This includes a description of observations and interviews.

Chapter 4, which focuses on structures, provides an example of the way in which institutional structures can influence community experience. Based around a discussion of ethical principles involved in negotiating the approval of a research project with an institution such as the Canadian Forces, I begin by explaining some of the existing tensions surrounding research with military institutions before providing an account of my own bureaucratic journey through the approval process of the Canadian Forces. I show that while it may be perceived as a bureaucratic hurdle, going through a research approval process was not only an ethical requirement, but also an important research tool. Through this process, I show that the institutions which have an interest in children can have impacts over them, and even some degree of control, even though they are not aware of it.

Chapter 5 focuses on the notion of agency and discusses how children shape their own social environments in various ways. To do so, I provide details of how children can bring changes and apply their agency to social environments such as their family, their school, and their town. I use the data collected during fieldwork to draw a portrait of community experience as a child of a military family in Cold Lake. These observations allow me to explain how various factors influence their experience of community as well as how they are themselves active participants in processes of cultural production and reproduction. In the following chapter, Chapter 6, I focus on some of the semiotic registers that are encountered by the children of École Voyageur, such as those concerning mobility. I explain how the French-speaking population of Cold Lake, Alberta, is mainly constituted by mobile individuals coming from two sectors: the oil industry and the Canadian military.

14

Based on my fieldwork in Cold Lake, I describe the impacts of having such a resident make-up on the community. From the parents, educators, and most importantly from the children‘s perspective, I ask how these mobile families relate to the many communities to which they belong, how they see themselves, and how they articulate their sense of belonging. Chapter 6 focuses on discourses on mobility that are common in the community and which contribute to creating and maintaining semiotic registers in which children of mobile families participate. This provides examples of how mobile individuals take part in semiotic encounters which in part define their community.

Drawing from the three preceding chapters, chapter 7 presents a discussion of the material from the perspective of encounters. Using examples from fieldwork, I explain how the experience of community from an individual perspective is the result of the encounter of agency, structures, and semiotic registers. I begin by showing how institutional structures of the Canadian Forces impact individual behaviour and orient some types of actions. I also discuss the complex situations which arise when a population is subject to the influence of overlapping, and sometimes competing, structures. Secondly, in great part drawing from discourse on mobility and mobile populations, I explain how an individual‘s framework for interpretation is shaped through interactions within chains of semiotic encounters, in a manner which is similar to that suggested by Agha (2007). Finally, focusing once more on children of military families at École Voyageur, I discuss how individual action has profound impacts, not only on how individuals experience community, but also in contributing to defining community itself. But first, I begin with the theoretical groundwork which will allow situating this research and its contributions.

15

Chapter 2

Theoretical Background

“One of the curious things about language is that it allows us to formulate models of phenomena that are highly abstract, even timeless; one of the curious things about our folkviews of language is their tendency to neglect what is obvious to our senses, namely that any such representation, however general in import, must be conveyed by a perceivable thing – i.e., be materially embodied – in order to become known to someone, or communicable to another. These moments of being made, grasped, and communicated are the central moments through which reflexive models of language and culture have a social life at all. And persons who live by these models (or change them) do so only by participating in these moments” (Agha 2007, 1-2)

2.1 Introduction

Like Agha (2007), I consider that language is of primary importance in orienting our experience of social environments and that meaning is not an essential value of the world around us but an attribute which emerges as we engage with it and participate in communicative encounters. In fact, as Ahearn (2001) points out, most linguistic anthropologists will see language not only as a tool which orients and frames our experiences, but also as a process through which we continually contribute to building, reproducing, and transforming social structures – as social action. This perspective puts

16

communication and interaction at the centre of attempts to understand how any individual experiences the communities they encounter and how they define their own identity. In this context, interaction is understood widely as a simple communication of meaning between individuals, be it directly in face-to-face dialogue or through intermediaries such as mass media, cultural consumption, public discourse, and signs. In fact, public policies and institutional structures can be seen as manifestation of a certain understanding of how society and organisations should work, such that individuals encountering them can be considered as interacting with them, and to be indirectly subjected to the discourses they represent. An example of such interaction is that of individuals with the military institution that is discussed in further detail in chapter 4.

The premise that meaning is an attribute of engagement supposes an understanding of key theoretical concepts. In this chapter, I provide the necessary theoretical background to situate the research and provide grounding for the discussions in the remainder of this dissertation.

This research project is in part inspired from previous works in a number of anthropological fields of inquiry. I will therefore first situate it in relation to anthropological perspectives on the military, on childhood, and on mobility, particularly from the perspective of the family. Following this a number of theoretical concepts of importance in this dissertation are presented and discussed. I begin with the notion of agency, for which I suggest adopting a flexible perspective allowing considering the subtle ways in which children can impact their environments. I also define the terms community and discourse, as they are theoretical concepts which have been used in a wide number of perspectives. Another element requiring discussion is the semiotic register which, while related to the notion of discourse, differs in that it constitutes an analytical tool used in this dissertation to reconcile dynamics of individual perspectives and personal experience of social environments with notions of cultural and institutional group identity.

17

2.2 An Anthropology of the Military

One of the defining identifiers of the individuals at the centre of this research is that they are children of military families. This dissertation explains various implications of this characteristic on their lives, in various sectors of their social environments. In order to situate this reflection, I discuss below some key elements of academic work on military communities. I begin by exploring the debated concept of military culture as it is one of the primary elements used to explain challenges in civil-military relations. Following this, I explain some of the unique tensions in civil-military relations through discussing conflicts of military institutional demands and priorities of the military members‘ families. In the context of this discussion I understand the military to be a valuable subject of anthropological inquiry as it provides material to help better understand complex relations between subsets of a population as well as concepts such as identity, practice, nationalism and identity.

2.2.1 Military culture

While engaging with individuals who experience situations of contact between military and civilians during fieldwork, differences of perspectives were often mentioned, that is, values and outlooks which create a divide between people who otherwise share similar backgrounds. For example, many participants interviewed during this research, both military and civilian, children and adults, expressed that civilians could not properly understand elements of the military lifestyle.

One spouse of a military member would tell me of conversations she had had with civilian acquaintances, where her interlocutor would sympathize with her situation when her husband was away on deployment. She would appreciate the intent, but also expressed some frustration, because she felt her situation minimized. Her friend had told her that she understood her situation as she also had been left alone at home with her children for a few weeks while her husband was away on a trip. The military spouse strongly felt that this comparison was unjustified, and that her friends‘ experiences did not justify her understanding of her own situation, in which her husband was away for up to 6 months, in high stress situations, and would likely be deployed again sometime in the future. The

18

frustration came from the fact that the civilian thought she could relate to the military spouse‘s situation, and that the feeling was not reciprocal. In fact, this discourse of misunderstanding between civilians and military members and their families is so common that it is possible that in itself contributes to the sense of disconnect. One could wonder if being constantly surrounded by a discourse which speaks of differences in lifestyles does not create, or at least contribute to the sense of isolation. Maybe being part of the military community involves taking part in this discourse and developing the sense of not being civilian, regardless of the actual differences in lifestyles. In this case, one could look at this discourse as a strategy in boundary maintenance similar to that described by Fredrick Barth (1969). Whether this is the result of systemic constraints on lifestyle or of enculturation within a different subculture, it remains that the concept of military culture is instrumental in how this gap is understood.

In the past, Canadian anthropology has contributed very little to the social research on contemporary military institutions. This is in part due to anthropology's focus on ‗exotic‘ cultures along with some discomforts in working with military institutions, particularly for researchers of American origin. Notably, individuals such as David Price documented a history of contestation and collaboration between anthropologists and American defence and security agencies (Price 2011, 2008, 2004). Among others, he produced work exploring the relationship between anthropologists and the FBI and CIA, their involvement with government agencies during the Cold War, as well as more recent collaboration with the American military, including through the Human Terrain System (HTS). Throughout, he describes uneasiness in relation to the nuances which must be articulated in order to accommodate professional and ethical guidelines in such contexts.

However, anthropology is well suited to the study of military communities, who abound with elements of interest to its practitioners such as jargon, traditions, rituals, and distinct worldviews. They can therefore be studied with the same approach taken to study any cultural group. Indeed, some openly talk of the existence of a military culture which has to be accounted for in order to understand the military as well as civil-military relations in particular (Académie Canadienne de la Défense 2003, English 2004, Winslow 1997). In

19 their own publications (Académie Canadienne de la Défense 2003), the Canadian Forces talk about military ethos, which represent values and worldviews which can be equated with elements of a promoted institutional culture. The Canadian Forces thus present a set of Canadian military values (duty, loyalty, integrity), which gives an opportunity to articulate fundamental beliefs and expectations of the military career (unlimited liability, fighting spirit, discipline, teamwork) within a wider framework of Canadian values.

Canadian military values — which are essential for conducting the full range of military operations, up to and including warfighting — come from what history and experience teach about the importance of moral factors in operations, especially the personal qualities that military professionals must possess to prevail. But military values must always be in harmony and never in conflict with Canadian values.

(Department of National Defence 2003, 30)

Others, such as Harrisson and Laliberté (1997, 1994) and Winslow (1997) focus on elements of military culture which can be problematic because of the divergence with civilians‘ values. For example, Winslow (1997, 15) cites Cockerham and Cohen (1980) to express the level at which civilians and militaries are divided by a redefinition of what are acceptably social acts: ―…what most distinguishes the military is that it must train and socialize its membership to norms that are non-normative in civilian society, such as kill people and obey orders implicitly‖.

The common point is that there is a general agreement that military members are subjected to a military culture which is distinct from that of civilians, and that their values and practices can sometimes be at odds with that of the general population. However, while military organisations across national borders may share elements of this organisational culture because it is formed in practice through the nature of military activities, it remains important to consider national and local re-articulations of these characteristics in specific contexts. While what is considered Canadian military culture contains elements that are typical of military organisations, it is re-defined and actualized in relation to a Canadian national reality, which allows the legitimization of the Canadian Forces. We must therefore take into account that in Cold Lake the reality of military life and the influence of the military institution on the family is played out in locally unique ways. In this sense, it is

20

useful to consider the situation in terms of Pierre Bourdieu‘s notion of habitus (Bourdieu 1977). Instead of considering military and civilian cultures from essentialist perspectives, the concepts presented through practice theory allow us to understand the various outlooks, values and predispositions shared by groups of individuals as resulting from shared experiences and of navigating social environments which belong to similar fields. Throughout this dissertation, the use of this theoretical perspective on culture proves useful as it corresponds with the nature of experiences and discourses collected in regards to concepts of identity and community. Indeed, military members and civilians whom I met in Cold Lake tended to articulate their identity as consequences of particular trajectories rather than as some intrinsic element of their personality associated with natural predispositions. While it is likely that individuals who join the military occupation may share in some general outlooks, military members come from a variety of backgrounds and it is therefore through the shared experience of socialization processes, and through practice of a profession within certain institutional and semiotic frameworks, that the military identity is forged.

2.2.2 Institutional Demands

As I have discussed elsewhere (Asselin 2007), the Canadian military, along with military institutions in general, can be described as a greedy institution. The term coined by Lewis Coser (1974), presented in relation to Erving Goffman's total institutions (1961), describes an institution which requires a complete commitment from its members, even though it may not encompass their entire lives. Indeed, military forces expect the complete dedication and unwavering loyalty of their members to be able to maintain operational efficiency. In fact, even in the face of a growing tendency of seeing a military career with an occupational approach (Moskos, Williams and Segal 2000), the main discourse in the military forces presents the profession of arms as ―a job like no other‖, as a vocation or an answer to a call which is accompanied by a sense of purpose (Académie Canadienne de la Défense 2003). Military members are expected to make sacrifices in order to have a successful career. Some of these sacrifices are explicit. For instance, upon enlistment, military members must agree to a clause of unlimited liability under which it is understood

21 that all legitimate orders must be obeyed even if these put the member at risk, possibly of losing his or her own life. I believe that this characteristic of the military forces is central to understanding military life and civil-military relations, as it explains much of its attitudes towards other groups who would seek their members' loyalty. One group which seeks such loyalty is the family.

2.2.3 Military families

If, in the words of Lewis Coser (1974, 4), greedy institutions ―seek exclusive and undivided loyalty and attempt to reduce the claims of competing roles and status positions on those they wish to encompass within their boundaries.‖, institution such as the family, that command considerable loyalty, can be problematic. Indeed, Mady Wechsler Segal (1986) positioned the family as another greedy institution. In many Western cultures, the fact that priority be given to one‘s family is generally accepted. This is generally accompanied by a relatively clear separation between private and public spheres of activity, with the family firmly entrenched within former and employment in the latter. Other than exceptions such as family businesses, this division of work and family is seen as fairly clear. Prioritizing family members in a public, professional setting would be seen as nepotism.

Instead of monopolizing its members' loyalty by cutting out the family, the military institution's strategy has been to include military families in its community. This fosters the creation of a sense of belonging, not only for military members but also for their civilian spouses who also can develop loyalty towards the institution, which then allows the Canadian Forces to demand from them certain sacrifices. Be it through the enlisted member, or through their own involvement in the military community, spouses of military members participate, contribute, and to some extent belong in the institution. However, can the same thing be said of their children? Do military children share a sense of belonging to the military community? Are they expected, explicitly or implicitly, to make contributions and/or sacrifices for the sake of operational efficiency? Alternatively, are they being purposefully excluded from the military world by their parents, so as to withdraw them from its influence? Some of these questions have recently been explored by Claire Corriveau in two documentary films on military families. However, Corriveau explores the

22

challenges facing military families from a different perspective. In her first documentary, entitled Nomad‘s Land (Corriveau 2007), she focuses on the impacts of the military lifestyle, including mobility on spouses and families of military members, but do not delve into the children‘s experiences of community. While her second documentary, Children of Soldiers (Corriveau 2010), focuses on children, the main element that is explored is the impact of deployment and sacrifice on children and family. While Corriveau‘s work contributes towards building a portrait of Canadian military families, more work is required to give an adequate account of the relationship between children of military families and their social environments. While deployment is one of the most obvious and taxing demands on military families, it is not the only activities which impact them. Another element of the military lifestyle which impact families and children of military members is the high degree of mobility which is involved in the military career, and which comes under scrutiny within this dissertation.

It is questions such as these that an anthropological approach to the military is particularly well suited to examine. Through looking at the military from an anthropological perspective, I recognize the complex interrelation of concepts such as military culture and the impact of military institutions on individuals and organisations, both military and civilian. Considering these observations within a holistic approach, the anthropology of the military is also interconnected with other aspects of anthropological inquiry, such as the anthropology of childhood.

2.3 The Anthropology of Childhood

Children of military families, and the individuals revolving around them, are the centre of this research and as such, a thorough review of previous anthropological work on childhood and the family is necessary. The following section provides an overview of key concepts from the anthropology of childhood placed in relation to this project. I begin by highlighting some of the recent calls for a child-centered anthropology before discussing

23 some of the dominant perceptions of the concepts of childhood and adolescence in an anthropological perspective. Finally, I discuss the role of children within communities along with some theoretical perspectives on their contributions to cultural reproduction.

2.3.1 Child-centered anthropology

In the last twenty years, there has been a renewal of interest in the study of children in anthropology (Lancy 2008, LeVine 2007, Montgomery 2009). While children have been part of the anthropological landscape for a long time, what the recent movement suggests is an extensive change of focus. A common critique is that while children were being talked

about in general terms in ethnographic work, there was a lack of research focusing

specifically on children (Montgomery 2009). Many anthropologists have tried to understand why this is the case. Hirschfeld (2002) for instance suggests two main reasons why there is little anthropological work focusing on children even though they are at the centre of cultural reproduction. He points to an ―overestimation of the role of adults in cultural reproduction‖ along with a ―lack of appreciation for the scope of the force of children culture, in particular in shaping adult culture‖ (Hirschfeld 2002, 611). This idea that children should be looked at as evolving within their own cultural world is a common thread among many theorists. To explain this point, Hirschfeld quotes Harris (1998) stating:

A child's goal is not to become a successful adult, any more than a prisoner's goal is to become a successful guard. A child's goal is to be a successful child.... Children are not incompetent members of adults' society; they are competent members of their own society, which has its own standards and its own culture. Like prisoner's culture and the Deaf culture, a children's culture is loosely based on the majority adult culture within which it exists. But it adapts the majority adult culture to its own purposes and it includes elements that are lacking in the adult culture. [Harris 1998:198-199].

(Hirschfeld 2002, 615)

The comparison between children and prisoners may seem somewhat charged, but the idea that the study of children should take into consideration power relations is supported by others. Hardman (2001), in her questioning on the possibility of there being an anthropology of children, relates the matter to early feminist work and compares children‘s

24

situation to that of women as muted groups. It could therefore be anthropology‘s mission to provide a voice to these individuals who are sometime left unperceived by researchers working with more vocal members of society. In extending the label of children to teenagers, it is also necessary to consider where older children may be placed in regard to the voicelessness. While teenagers are often characterized as in the process of finding their voice, it remains that their perspectives are often look upon in paternalistic ways by the adult population. Therefore, while older children progressively gain more opportunity and capacity to express their opinions, the degree of concern awarded to these in many respects remains conform with the concept of muted group.

One of the elements that is central to child-centered anthropology is thus the need to look at children and their experiences in order to understand their reality here and now, rather than to explain what they will become. Although my research is not strictly speaking ―child-centered‖, this focus on child experience in and of itself is a perspective I advocate. When studying socialization processes, researchers try to understand how one develops competence in one‘s culture. However, the nature of the community I am studying creates problems in that regard. Military brats2, while being subjected and socialized to military culture, are not necessarily themselves destined to become members of an adult military community. While some children of military members do follow in their parents‘ footsteps, most of the late teenagers I encountered in Cold Lake had no aspirations of a military career. Furthermore, the mobility which is inherent to the military lifestyle makes it that children of military families are not even likely to be members of the towns in which they are raised. This context thus provides a good example of a situation where child experience should be understood for what it is in the moment, and not only in terms of what impact it will have on their community in the future.

A common endeavour among anthropologists promoting a child-centered anthropology is that of refuting the representation of children as incomplete individuals. Montgomery (2009) expresses this in term of human being vs. human becoming. The interest of

2 While the term brat can have negative connotations, the use of military brat is generally not seen as