Université de Montréal

Linking foodscapes and dietary behaviours: conceptual insights and

empirical explorations in Canadian urban areas

par Christelle Clary

Département de médecine sociale et préventive École de santé publique

Thèse présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Philosophiae Doctor (PhD) en Santé publique

option Promotion de la santé

Octobre, 2015

Université de Montréal

Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales

Cette thèse intitulée :

Linking foodscapes and dietary behaviours: conceptual insights and empirical explorations in Canadian urban areas

Présentée par Christelle Clary

A été évaluée par un jury composé des personnes suivantes :

Dr. Sylvana Côté, président-rapporteur Dr. Yan Kestens, directeur de recherche

Dr. Lynne Mongeau, membre du jury Dr. Jean-Michel Oppert, examinateur externe Dr. Marie Marquis, représentante du doyen de la FES

i

Résumé

La manière dont notre environnement influence le lieu et la nature de nos achats alimentaires n’est pas bien comprise. Un accès facilité ou limité aux commerces d’alimentation dits « sains » et « non-sains » a été considéré comme central dans la relation entre environnement et comportements alimentaires. De fait, la recherche a surtout tenté d’établir un lien entre, d’une part, facilité d’accès aux commerces « sains » et comportement sains, et, d’autre part, « déserts alimentaires » ‒ ces environnements socialement défavorisés offrant un accès limité aux sources d’alimentation saine ‒ et comportements non sains. Les écrits en santé publique manquent cependant de perspective sur les facteurs influençant le lieu et la nature des achats alimentaires dans les situations où les options qui s’offrent aux individus sont multiples, saines et moins saines. Pourtant, dans les villes occidentales caractérisées par une densité de commerces élevée et une mobilité individuelle facilitée, la réunion des conditions d’accès aux commerces d’alimentation « sains » comme moins « sains » est probablement situation courante.

Partant de ce constat, cette thèse explore le lien entre environnements et comportements alimentaires dans plusieurs grandes villes canadiennes. En premier lieu, un cadre conceptuel est proposé, qui décrit les multiples facteurs influençant le lieu et la nature des achats alimentaires. Partant du postulat couramment adopté selon lequel les individus cherchent à tirer un maximum de bénéfices de leur environnement, ce cadre souligne l’importance de considérer les caractéristiques des commerces d’alimentation « sains » et « non sains » (ex. localisation, prix) en relation avec les préférences, moyens et contraintes des individus. L’attention est cependant attirée sur la capacité limitée des individus à opérer des choix pleinement informés. En effet, la réalisation de ces choix s’opère parfois sans grande conscience, en réaction à certains stimuli environnementaux. Sont notamment discutées les situations dans lesquelles le caractère approprié d’un comportement alimentaire est implicitement suggéré par

ii

l’environnement. Il est proposé que les densités relatives de commerces alimentaires « sains » et « non-sains » dans l’environnement auquel les individus sont exposés reflèteraient la relative popularité de ces lieux d’achat, et suggèreraient quels types de commerce il est « approprié » d’utiliser.

Pour tester la plausibilité d’une telle proposition, cette thèse explore dans quelle mesure le pourcentage de commerces « sains » dans l’environnement des résidents adultes de cinq grands pôles urbains au Canada est associé à leur consommation de fruits et légumes. Les recherches présentées dans cette thèse portent à la fois sur les environnements autour du lieu de résidence (environnement résidentiel) et autour des divers lieux fréquentés par ces individus (environnement non résidentiel). Sont également testées d’éventuelles différences homme-femme dans ces associations, des différences de genre ayant été soulignées dans les recherches s’intéressant à la relation entre environnements et comportements alimentaires.

Conformément aux hypothèses émises, une association positive entre pourcentage de magasins « sains » dans l’environnement résidentiel et consommation de fruits et légumes est observée. Une relation plus forte chez les hommes que chez les femmes est également relevée. En revanche, la consommation de fruits et légumes n’est pas reliée au pourcentage de magasins « sains » dans l’environnement non résidentiel et ce, ni chez les hommes ni chez les femmes.

En proposant un cadre conceptuel innovant, que viennent en partie conforter les résultats de notre recherche empirique, cette thèse contribue à la construction d’une meilleure compréhension des influences environnementales sur les comportements de santé.

Mots-clés: environnement alimentaire; accès; exposition; environnements résidentiel et non résidentiel; comportements alimentaires; fruits et légumes; différences de genre; adultes; Canada.

iii

Summary

In westernised cities where food is mostly acquired in the retail and catering environment, there may be a link between the foodscape - i.e. the multiplicity of publicly available sites where food is displayed for purchase - and where and what we buy and eat. Yet, how the foodscape shapes dietary behaviours remains unclear. Ease and difficulty of access to “healthy” and “unhealthy” food sources has been recognised as central in the foodscape-diet relationship. As a result, empirical research has mostly investigated the associations between ease of access to healthy outlets and healthy behaviours, on one hand, and “food deserts” – deprived environments lacking access to healthy food outlets – and unhealthy behaviours, on the other hand. However, public health literature lacks perspective on the factors that influence where to purchase and what to eat in situations of multiple – healthy and less healthy – choices. Yet, in industrialised urban contexts characterised by pervasive food retail and facilitated individual mobility, conditions for accessing both healthy and less-healthy food sources are probably commonly met.

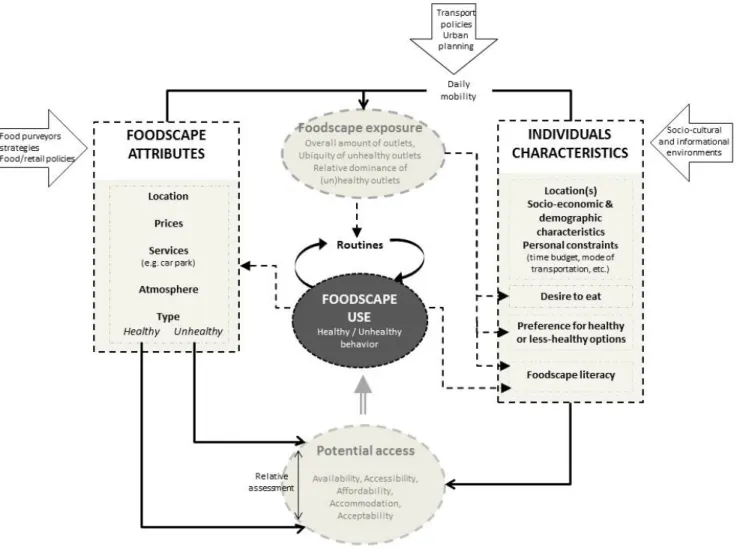

Based on these observations, this thesis intents to explore the relationship between foodscapes and dietary behaviours in Canadian urban areas. Firstly, conceptual insights on the multiple factors shaping where to shop and what to eat are provided. Drawing from the commonly held assumption that individuals operate choices that tend to maximize their self-interests, the proposal highlights the importance of considering food outlets’ characteristics (ex. localisation, price, services offered) relatively to individuals’ preferences, constraints and means. However attention is brought on individuals’ limited ability to operate fully-informed choices. Food choices sometimes unfold without much deliberation, as a result of the mere perception of cues in the environment. Especially discussed are the situations where exposure to cues signaling appropriateness of a dietary behaviour provokes the adoption of similar behaviours. It is then suggested that the relative densities of healthy and unhealthy outlets individuals

iv

get exposed to may drive a normative message about the relative popularity of these places, and suggest which places are “appropriate” to use.

This thesis then investigates the extent to which relative exposures to healthy and unhealthy food outlets are associated to dietary behaviours. Drawing on multiple secondary datasets pertaining to adult residents of five large Canadian cities, associations between the percentage of healthy outlets in the residential neighborhood and fruit and vegetables intake are examined. As literature highlighted gender differences in the foodscape-diet relationship, whether these associations are different for men and women are further investigated. Finally, these investigations extend to the non-residential environment.

Consistent with our expectations, our research provides evidence of a positive association between the percentage of healthy outlets around home and fruit and vegetable intake. Stronger associations for men than for women were further observed. However, fruit and vegetable intake was not related to the non-residential foodscape, neither for men nor for women.

By providing conceptual justification for, and empirical evidence of, a link between dietary behaviours and relative exposures to healthy and unhealthy outlets, this thesis contributes to better understand how the foodscape shapes dietary behaviours.

Keywords: foodscape; access; relative exposure; residential and non-residential environments; dietary behaviors; fruit and vegetable; gender-differences; adults; Canada.

v

Table of contents

Résumé ... i

Summary ... iii

Table of contents ... v

List of tables ... viii

List of figures ... ix

List of abbreviations ... x

Remerciements ... xi

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ... 13

1.1. From food deprivation to food abundance, the sustaining burden of diet-related diseases ... 14

1.2. Toward the increasing recognition of environmental influences on dietary behaviours ... 16

1.2.1. Advent of ecological models ... 16

1.2.2. Geographies of food retail and dietary behaviours: synchronised evolutions . 17 1.3. Linking foodscape and dietary behaviours ... 20

1.3.1. The central concept of access ... 20

1.3.2. Access and the question of alternatives: current positions and limitations ... 22

1.4. Thesis plan ... 26

CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 27

2.1. The ‘slippery’ notion of access ... 28

2.1.1. Distinguishing real from potential access ... 28

2.1.2. Earliest conceptual foundations of access ... 29

2.2. Is there only spatial accessibility in access? ... 32

2.2.1. Individuals’ mobility or the stretching opportunities for food shopping ... 32 2.2.2. Proximity… and the many other outlet characteristics influencing food outlet choice 34

vi

2.2.3. The multidimensional concept of access ... 35

2.3. Access to healthy outlets, to unhealthy outlets or to both? The disregarded question of alternatives ... 38

CHAPTER 3. CONCEPTUAL PROPOSAL ... 41

ARTICLE 1 ... 42

ABSTRACT ... 44

BACKGROUND ... 45

Access and the disregarded question of alternatives ... 49

Biological beings or foodscape’s propensity to stimulate food desire ... 51

Social beings or foodscape’s normative dimension ... 53

Food purchase routines ... 55

Towards the need to differentiate access from exposure ... 56

Implications for research ... 58

CONCLUSION ... 59

REFERENCES ... 61

CHAPTER 4. TWO EMPIRICAL CASE STUDIES: RELATIVE EXPOSURE TO HEALTHY AND UNHEALTHY OUTLETS AND FRUIT AND VEGETABLE INTAKE AMONG WOMEN AND MEN IN URBAN CANADA ... 73

4.1. Rationale ... 74

4.2. Specific objectives and research hypotheses ... 79

4.3. Methods ... 81

4.3.1. Study design and population ... 81

4.3.2. Variables ... 84 4.3.3. Analytical procedure ... 89 CHAPTER 5. RESULTS ... 91 ARTICLE 2 ... 92 ABSTRACT ... 94 INTRODUCTION ... 95 METHODS ... 96 RESULTS ... 100

vii DISCUSSION ... 105 CONCLUSION ... 107 REFERENCE LIST ... 109 ARTICLE 3 ... 114 ABSTRACT ... 118 INTRODUCTION ... 120 METHODS ... 123 RESULTS ... 128 DISCUSSION ... 133 CONCLUSION ... 135 REFERENCES ... 136 ANNEXE ... 140 CHAPTER 6. DISCUSSION ... 141

6.1. Executive summary and key findings ... 142

6.2. General interpretations and future research perspectives ... 144

6.3. Implication for public health policies ... 150

6.4. Limitations of the present research ... 152

6.4.1. Limitations on the way the foodscape was defined and operationalised ... 152

6.4.2. Issues pertaining to residential and non-residential exposure assessment ... 153

6.4.3. Issues pertaining to the study design... 155

CHAPTER 7. CONCLUSION ... 157

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 159

APPENDIX I ... xiii

viii

List of tables

ARTICLE 2

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics and dietary intakes of CCHS participants, Canada, 2007-2010………..p.101 Table 2 Associations between foodscape exposure and daily fruit and vegetable intake - Whole sample, Canada, 2007-2010 (N=49,403)……….…………..p.104 Table 3 Associations a between foodscape exposure and daily fruit and vegetable intake in gender- and CMA-stratified samples, Canada, 2007-2010………...p.105

ARTICLE 3

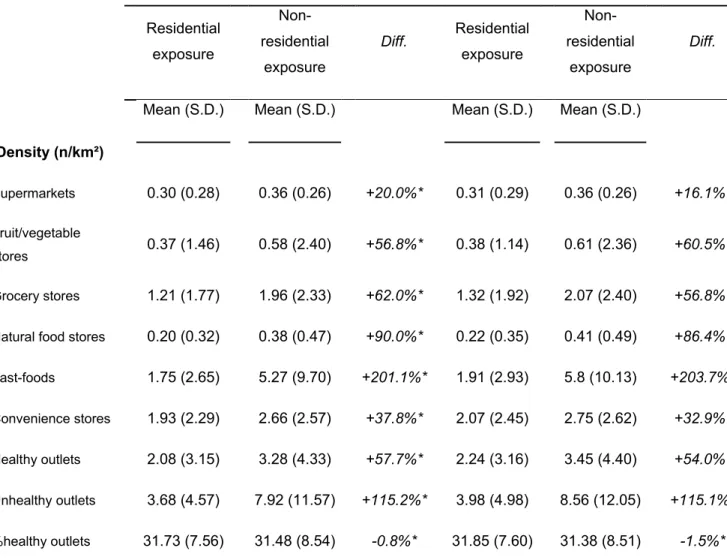

Table 1 Descriptive statistics for OD and CCHS participants……….p.129

Table 2 Descriptive statistics for residential and non-residential exposures for OD-participants………p.131

Table 3 Associations between foodscape exposure and fruit/vegetable intake, CCHS participants, Montreal, 2007-2010……….p.132

ix

List of figures

ARTICLE 1

Figure 1 Conceptual framework depicting foodscape influences on dietary behaviours…….……….p.48

x

List of abbreviations

AIC Aikake Information Criteria

CCHS Canadian Community Health Survey CMAs Census Metropolitan Areas

CT census tract

DA dissemination area

EPOI Enhanced Points of Interest FFQ food frequency questionnaire FFR fast-food restaurants

FSR full-service restaurants FVI fruit and vegetable intakes FVS fruit and vegetable stores

GIS Geographic Information Systems GWR geographically weighted regressions KDE Kernel Density Estimation

MCMA Montreal Census Metropolitan Area

MI Multiple Imputation NFS natural food stores OD Origin-Destination

RFEI Retail Food Environment Index SIC Standard Industrial Classification VIF Variance Inflation Factor

xi

Remerciements

Il serait bien inconsistant de consacrer une thèse au rôle de l’environnement sur l’action des individus, et ne pas reconnaitre les nombreuses contributions de mon entourage à ce travail de réflexion, d’analyse et d’écriture. Chaque étape qui a conduit à la production de cette thèse a été rendue possible par l’implication plus ou moins directe d’acteurs, dont je ne citerai que les principaux, mais que je remercie tous au-delà de ces mots.

Yan, merci pour la confiance que tu m’as accordée, pour ton inébranlable optimisme qui m’a encouragée à persévérer, et pour avoir élargi mon horizon intellectuel.

Merci Louise pour tes cours. Ils furent pour moi une manière nouvelle et inspirante de recevoir un enseignement.

Merci Yuddy pour ton soutien et ta bonhomie, et Martine pour tes encouragements et pour avoir été un exemple à suivre.

Benoit, merci d’avoir été si généreux en bons conseils. Il était rassurant de savoir qu’aucun souci technique ne résisterait une fois franchi le seuil de ton bureau.

Merci à Camille, Cat, Thomas, Stéphanie, Tarik, Julie, Annie, Marie A. et Claire B. pour m’avoir permis de garder l’équilibre et voir « le verre toujours à moitié plein ».

Je remercie également Jean-Louis Lambert et Bernard Maire, mes anciens professeurs de l’ENITIAA et de l’IRD, pour m’avoir épaulée dans mon désir d’entreprendre une thèse.

Merci à ma famille pour m’avoir aidée à me construire et à rendre possible la réalisation de ce projet.

xii

Merci enfin à Matthew, par qui tout a commencé, et sans qui rien n’aurait pu aboutir. Et à ma fille Chloé, qui donne tout son sens à ma démarche et à mon espoir de voir se construire une société plus en santé.

14

1.1. From food deprivation to food abundance, the sustaining burden of diet-related diseases

For millennia, the human race struggled to overcome hostile environments, food scarcity and undernutrition-related diseases. From the earliest forms of agriculture to the advent of the industrial revolution, humans have continuously sought to push aside the limits of food insecurity (Weill 2007). Well-fed individuals are necessary to healthy populations and, in turn, social equilibrium, a good economy and the political might of nations. Accordingly, countries have intended to increase food availability for their growing populations by supporting the development of efficient food systems based on intensive farming practices, mechanical and computerized food-processing (Cotterill 1992; Caballero 2007), novel foods (Cordain, Eaton et al. 2005) and large-scale retailing (Wrigley and Lowe 1998). Partly as a result of these efforts, westernised countries have progressively seen the height, weight and life expectancy of their population increase (Caballero 2007). Yet from the 1950s onwards and the raging epidemic of diet-related chronic diseases across industrialised countries (WHO/FAO 2003), the challenge of feeding people became of a different nature for governments (Caraher and Coveney 2004).

From the mid-20th century, epidemiological studies have pointed out the existence of a link between the nutritional quality of diet and a set of increasingly prevalent chronic diseases (Dawber, Meadors et al. 1951; Keys, Menotti et al. 1986), including type 2 diabetes (van Dam, Rimm et al. 2002; Hu 2011), cardiovascular diseases (Fung, Willett et al. 2001; Mente, de Koning et al. 2009; Lee, Kim et al. 2011), and certain cancers (Hill 1987; Block, Patterson et al. 1992; Slattery, Boucher et al. 1998). For instance, abundant research agreed on the health-detrimental effect of high intakes of sugar (Malik, Popkin et al. 2010; Malik, Pan et al. 2013; Yang, Zhang et al. 2014) and saturated

15

fat (Hu, Manson et al. 2001; Mozaffarian, Katan et al. 2006). Inversely, the protective effect on health of certain foods like fruit and vegetable was widely recognised (Ness and Powles 1997; Liu, Manson et al. 2000; Lock, Pomerleau et al. 2005; Pomerleau, Lock et al. 2006; Wang, Ouyang et al. 2014). Hence, it has been acknowledged that it is not just the overall quantity of foods consumed by populations that matters, but also the nutritional quality of these foods.

The enormous costs of nutrition-related diseases for governments, and their dramatic consequences on people’s life (Gortmaker, Must et al. 1993; Wellman and Friedberg 2002), have pushed health authorities to adopt preventive measures (Tunstall-Pedoe 2006). The political individualism dominant from the 1950s onwards in many industrialised countries, added with methodological and conceptual emphasis on risk factors in epidemiological studies, encouraged countries to adopt behavioural change perspectives among at-risk individuals (Macintyre, Ellaway et al. 2002). Health authorities came up with nutritional guidelines providing recommendations on the target amount or frequency of consumption of foods deemed to play a key role in a balanced diet (Nishida, Uauy et al. 2004). Educational programs were implemented (Sherwin, Kaelber et al. 1981; Farquhar, Fortmann et al. 1985; WHO 1997; Antipatis, Kumanyika et al. 1999) with intent to shift unhealthy diets towards diets more consistent with these national guidelines. Yet, the spread of chronic diseases kept occurring in the face of increasing education about nutrition (Foreyt, Goodrick et al. 1981; Carleton, Lasater et al. 1995; Orleans 2000).

16

1.2. Toward the increasing recognition of environmental influences on dietary behaviours

1.2.1. Advent of ecological models

Nurtured by the observation of social (Steele, Dobson et al. 1991; Roos, Lahelma et al. 1998; Martikainen, Brunner et al. 2003) and spatial (Daniel, Kestens et al. 2009; Lebel, Pampalon et al. 2009; Michimi and Wimberly 2010) patterning of dietary behaviours, the late 1990s have seen research interest redirected towards environmental effects on health behaviours (Macintyre, Ellaway et al. 2002; Entwisle 2007). With the advent of ecological models for health promotion over that same period (Sallis, Owen et al. 2008; Richard, Gauvin et al. 2011), physical and social environments became increasingly recognised as potent determinants of what we eat (Booth, Sallis et al. 2001; Glanz, Sallis et al. 2005). A central tenet of ecological models is that it usually takes the combination of both individual and environmental factors to explain health behaviours (Sallis, Owen et al. 2008). For instance, individuals with strong health awareness may be limited in their intent to consume fruit and vegetables if their environment does not readily provide such foods. Inversely, living in an environment providing plentiful fruit and vegetables does no guarantee that people will make use of that resource. In short, healthy behaviours are thought to be maximized when environments support healthy choices, and individuals are motivated to make those choices (WHO 1986; Wang, MacLeod et al. 2007). Alongside keeping on educating people, the public health nutrition field has therefore sought to identify the promoting and health-detrimental features of the food environment (Holsten 2009; Giskes, van Lenthe et al. 2011).

17

1.2.2. Geographies of food retail and dietary behaviours: synchronised evolutions

In the westernised world where food is mostly acquired through market-guided systems (Eckert and Shetty 2011), attention has been especially directed towards the retailing and catering environment, or foodscape, defined as the multiplicity of publicly available sites where food is displayed for purchase (Winson 2004). The 1950s onwards have witnessed considerable changes in the foodscape across most industrialised countries, especially in North America. The emergence of large chain-owned supermarkets on the edge of towns (Cotterill 1992; Wrigley 1998; Guy, Clarke et al. 2004; Einarsson 2008) and more recently their inner-city reduced-scale variant (Jeffery, Baxter et al. 2006; White 2007; Cohen 2008; Black, Moon et al. 2014), has resulted in a decline in the number of smaller general and specialist grocery shops (Wilson and Oulton 1983; Fotheringham and Knudsen 1986; Cotterill 1992; Guy 1996; Wrigley 1998; Guy, Clarke et al. 2004; White 2007). Chaining allowed retailers to lower operating costs, while offering a great selection of goods, undermining the attractiveness of local grocers (Wrigley and Lowe 1998). In parallel, cities have witnessed the rapid multiplication of fast-food restaurants and convenience stores (Cotterill 1992; Wrigley 1998; Guy, Clarke et al. 2004).

Overall, this evolution led to an increased availability of food at the city scale. Yet, from a public health nutrition perspective, this should be considered with a more nuanced view. Food outlets are not similar in quality from a health standpoint. Studies have pointed out in-store disparities in the availability of both healthy and unhealthy foods. Overall, supermarkets, fruit and vegetable stores and grocery stores propose a wider range of food items whose consumption is advocated by health authorities (e.g. fruit and vegetables) than convenience stores and fast-food restaurants (Lewis, Sloane et al. 2005; Rose, Bodor et al. 2009; Reedy, Krebs-Smith et al. 2010; Ohri-Vachaspati, Martinez et al. 2011; Black, Ntani et al. 2014). They also have a greater ratio of the total

18

shelf space dedicated to healthy food items to the total shelf space dedicated to unhealthy items (Farley, Rice et al. 2009; Zenk, Powell et al. 2014). Now, there is some evidence that the higher the availability of healthy foods in stores, the higher the quality of customers’ diet (Cheadle, Psaty et al. 1991; Fisher and Strogatz 1999; Zenk, Schulz et al. 2005; D'Angelo, Suratkar et al. 2011; Aggarwal, Cook et al. 2014). This makes sense in the light of marketing research on shelf space demonstrating that supply can drive demand (Curhan 1973; Curhan 1974; Chevalier 1975; Wilkinson, Mason et al. 1982; Desmet and Renaudin 1998; Eisend 2014). Drawing on the assumption that food outlet type influences food choice, supermarkets (chain and independent), grocery stores and fruit and vegetable stores/markets have been traditionally referred to as “healthy” resources, while convenience stores and fast-food restaurants as “unhealthy” ones (Sallis, Nader et al. 1986; Horowitz, Colson et al. 2004; Ohri-Vachaspati, Martinez et al. 2011; Cannuscio, Tappe et al. 2013; Black, Ntani et al. 2014).

From a public health perspective, this retail evolution has hence been marked by two trends: on one hand, the transition from small-scale and dispersed to large-scale and clustered healthy food sources, and on the other hand, the local invasion of unhealthy food stores. Recent research has consistently reported an overwhelming predominance in the number of unhealthy outlets compared to healthy ones. For instance, there are almost 12.5 times more fast-food outlets than supermarkets in Edmonton (Smoyer-Tomic, Spence et al. 2008). Cannuscio et al. have reported that convenience stores comprise almost 80% of the food retail outlets in the 30 Philadelphia city blocks they have studied (Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014). The average California adult is exposed to four times as many fast-food restaurant and convenience stores than supermarkets, grocery stores and markets (Babey, Diamant et al. 2008). Consistently, the residential neighbourhood of adults living in one of the five largest Canadian cities encloses on average three times as many unhealthy outlets than healthy outlets (Clary, Ramos et al. 2014). In a similar vein, a study based in Cambridgeshire, UK, reported an

19

overwhelming majority of convenience stores and takeaways/fast-food restaurants compared to supermarkets, both around home and work places of the participants (Burgoine and Monsivais 2013).

Locally, this evolution has resulted in disparities in the availability of food resources, with areas facing a disproportionate lack of healthy food resources or abundance of unhealthy ones. Depicted through the metaphor of “urban grocery store gaps” (Cotterill and Franklin 1995) these trends have been well-documented (Smoyer-Tomic, Spence et al. 2008), especially in the field of social justice interested in disparities with regard to neighbourhood-level SES. Overall, this literature has consistently referenced unequal distribution across urban neighbourhoods, both regarding supermarkets (Cotterill and Franklin 1995; Moore and Diez Roux 2006; Ford and Dzewaltowski 2008; Larson, Story et al. 2009; Lovasi, Hutson et al. 2009; Rose, Bodor et al. 2009; Walker, Keane et al. 2010) - chain and non-chain (Powell, Slater et al. 2007), grocery stores (Moore and Diez Roux 2006; Powell, Slater et al. 2007; Beaulac, Kristjansson et al. 2009; Walker, Keane et al. 2010), convenience stores (Powell, Slater et al. 2007; Rose, Bodor et al. 2009), fast-food restaurants (Powell, Chaloupka et al. 2007; Smoyer-Tomic, Spence et al. 2008; Daniel, Kestens et al. 2009; Larson, Story et al. 2009; Lovasi, Hutson et al. 2009; Fraser, Edwards et al. 2010; Hilmers, Hilmers et al. 2012), but also fruit and vegetable stores, bakeries, specialty stores, and natural food stores (Moore and Diez Roux 2006).

Parallel to this food retail evolution, westernised countries have witnessed significant changes in dietary behaviours, both regarding the quality of the diet and the mode of consumption. There is consistent evidence of a shift towards more refined sugar (HCSP 2000; Popkin and Nielsen 2003; Cordain, Eaton et al. 2005; Garriguet 2007; Wells and Buzby 2008) – partly linked to increased soft drink intakes (Harnack, Stang et al. 1999; Popkin and Nielsen 2003; Nielsen and Popkin 2004), and fat (Chevassus-Agnès 1994; USDA 1998; HCSP 2000; Cordain, Eaton et al. 2005; Garriguet 2007; Wells and Buzby 2008). Concomitantly, an increase in away-from-home eating practices has been reported (Zizza, Siega-Riz et al. 2001; Popkin and Nielsen 2003; Garriguet 2007). Those

20

changes have been particularly well documented in North America, but similar trends have been observed in Europe (Ziegler 1967; Cordain, Eaton et al. 2005; Hébel 2011). The potential impact of this changing foodscape on local consumer’s dietary behaviours has therefore been the focus of many studies.

1.3. Linking foodscape and dietary behaviours

1.3.1. The central concept of access

It has been largely accepted that the foodscape influences dietary behaviours by enabling or limiting the acquisition of healthy and unhealthy foods (Story, Kaphingst et al. 2008). Driven by the fundamental assumption that the effort to reach a food resource declines with decreasing distance from home, especially due to time and transportation cost (Pacione 1974; Brown 1989), research has mainly approached the question of access to food resources in terms of spatial accessibility (Charreire, Casey et al. 2010). Under that perspective, consumers have been assumed to patronize the nearest places from home that offer the required goods or services. The type(s) of food resources located in close vicinity from home have hence been presumed to shape dietary behaviours (Charreire, Casey et al. 2010; Caspi, Sorensen et al. 2012; Black, Moon et al. 2014). In the context of disparities in the healthy and unhealthy food outlets distributions (described above), a considerable amount of research has assessed the extent to which shortened distance from home to, or increased density around home of healthy and unhealthy food sources would relate to dietary behaviours. Particularly prolific, research on ‘food deserts’ has focused on the situation where poor

21

people live in residential areas lacking healthy food options (Cummins and Macintyre 2002).

Yet, discrepancies in findings (Charreire, Casey et al. 2010; Caspi, Sorensen et al. 2012) have pushed researchers to question the conceptual positions they were relying on regarding how the foodscape relates to dietary behaviours (Cummins, Curtis et al. 2007; Lytle 2009). In recent years, conceptual refinements of access have been driven by two considerations. First, in an era of facilitated mobility (Miller 2007), individuals actually tend to purchase food outside their residential neighbourhood (Day 1973; Inagami, Cohen et al. 2006; Hillier, Cannuscio et al. 2011; Kerr, Frank et al. 2012). Thus, defining access exclusively as a measure of spatial accessibility to local amenities is misleading and may explain why research based on proximity-driven conceptualisations of access has shown discrepancies. Second, an extensive host of research has reported that a wide range of outlets’ characteristics including prices policy (Drewnowski, Aggarwal et al. 2012), facilities provided (e.g. car park (Widener, Metcalf et al. 2011; Chen and Clark 2013)), and point-of-sale atmosphere (e.g. kid-friendly (Ayala, Mueller et al. 2005)) also inform the decision making process regarding where to shop and what to eat (Smith and Sanchez 2003; Krukowski, Sparks et al. 2013). Accordingly, contemporary research on the foodscape has mostly stood behind the assumption that individuals rationally evaluate food outlets on a set of attributes (e.g. price, location, services provided) and then patronize the option that will best accommodate their desire and means (financial, material, etc.) (Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014). Under that perspective, both the characteristics of individuals and the characteristics of food outlets interrelate to create the conditions of use. It has therefore been suggested that environmental and individual features should be looked at in a relational approach (Cummins, Curtis et al. 2007). Drawing from Penchansky and Thomas’s work on access (Penchansky and Thomas 1981), current reflections on access have suggested to measure the level of access one has of a given food outlet type by assessing the ‘fit’ between the individuals’ and outlets’ characteristics. A good ‘fit’ was deemed to make a given type of outlet a

22

potential candidate for use. When either healthy or unhealthy outlets were deemed potential candidates for use, then the foodscape was considered either health-promoting or health-detrimental, respectively.

Yet, in urban contexts, food retail is pervasive (Fielding and Simon 2011), and mobility facilitated (Miller 2007). Without dismissing food insecurity, which remains a major issue for some people, situations where both healthy and less-healthy food outlets are potential candidates for use are certainly common. In this case, is the foodscape’s influence positive or negative on health behaviours? In sum, the question may not only be whether healthy and unhealthy food resources, taken separately, are potentially accessible, but also how likely healthy options are to be chosen in a situation where both healthy and unhealthy resources are potential candidates for use. Yet, we argue that current conceptual positions on access fail to provide comprehensive insights on the factors which push individuals to select a healthy rather than a less-healthy option (and vice-versa) when found in a position of choice. Overall, there is a need to bring further understanding of the decision making process for healthy and less-healthy food outlet choice.

1.3.2. Access and the question of alternatives: current positions and limitations

Individuals are often presumed to be engaged ‘actively, rationally and creatively’ with the foodscape (Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014), that is, ‘act in their own self-interest with full awareness of how that self-interest is achieved’ (Welsh and MacRae 1998). This means for consumers to objectively evaluate food outlets on a set of attributes and then patronize the best option given their preferences, means and constraints (Bhatnagar and Ratchford 2004). Put differently, food choices are assumed to describe

23

a fully-informed preferential behaviour toward one (or a few) option(s) out of a larger field containing competing alternatives.

In the cases where consumers’ primary concern(s) relate to questions of proximity, price, convenience, or point-of-sale atmosphere (or a combination of those), the place actually selected will be healthy only if this place is more advantageous with regard to these aspects than the less-healthy alternatives also evaluated. Rose et al. have therefore suggested that a sound conceptualisation of access should consider the

relative assessment of healthy and unhealthy food outlets with regard to relevant

criteria for choice (Rose, Bodor et al. 2009). In the cases where the healthfulness of food outlets is a concern, beyond questions of proximity, price, or convenience, the outlet selected will be healthy if the individual is inclined to prefer healthy behaviors, and unhealthy in the opposite case. Consequently, a comprehensive conceptualisation of access should also be informed by influences on motivation to shop/eat at healthy or less-healthy places. Inclination for healthy and less-healthy food options are commonly presumed to be shaped by genetic predispositions (Brown and Ogden 2004) and, throughout the life-course, by both the sociocultural (e.g. family (Benton 2004; Delormier, Frohlich et al. 2009), local residents (Delormier, Frohlich et al. 2009; Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014)) and the ‘information’ environments – the latter referring to food marketing and advertising (Glanz, Sallis et al. 2005). In sum, the dominant conceptual position of access is nurtured by two tenets. First, people consciously process information before they decide where and what to buy or eat (Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014). Second, they tend to opt for the option that is optimally satisfying, with regard to a set of consciously assessed outlet characteristics such as proximity, price, convenience, social atmosphere and healthfulness.

Although one cannot reasonably deny that outlet choice relies to some extent on a rational decision-making process, we argue that considering individuals as utility-maximizers with full awareness of how to achieve this maximisation is challenged in the view of two elements. First, maximising one’s interest implies to have a clear idea about

24

the relative priority one attaches to different store characteristics. Yet, there is little evidence that individuals are able to readily identify their own priorities when it comes to food purchase. In a study by Krukowski et al., surveyed individuals who were asked to spontaneously report the two most important factors for food store choice evoked most often proximity from home and price. Yet, among the very same group of people, freshness of meat and a well-maintained store were the two factors from a list of 49 factors including proximity and price that gathered the average highest ranking for importance in food store selection (Krukowski, Sparks et al. 2013). The fact that individuals rank factors for food store choice differently when those factors are considered spontaneously or as part of a list illustrates the complexity that surrounds the decision for food store choice in a context of many available options. In sum, choices tend to be satisfying, rather than optimal (Brown, 1993). Second, recent work in the field of environmental psychology and retail marketing suggests that the ability to exercise conscious and intentional choices is actually quite limited (Dijksterhuis, Smith et al. 2005; Cohen and Farley 2008). Laboratory and in-store experiments have demonstrated that food choice often unfolds unconsciously as a result of the mere perception of cues in the environment (Dijksterhuis, Smith et al. 2005; Cohen and Farley 2008). For instance, increased shelf space dedicated to a given food item is steadily followed by increased sales of this item (Curhan 1973; Curhan 1974; Chevalier 1975; Wilkinson, Mason et al. 1982; Desmet and Renaudin 1998; Eisend 2014), proving that supply drives consumers’ behaviours. Relying on external cues is assumed to be an automatic mechanism naturally developed to ease the decision-making process through reduced brain involvement – ‘involvement’ here referring to feelings of interest, concern and enthusiasm held towards something (Beharrell and Denison 1995). This may be especially true nowadays; in the complex context food choices are made, what, how much and where to eat is rendered especially difficult to monitor (Bargh and Chartrand 1999; Wansink 2004). Returning to the example of shelf space driving sales, it has been suggested that if a product is given a large shelf space, it is more likely to be seen by customers and, in turn, purchased more frequently (Dreze,

25

Hoch et al. 1995; Desmet and Renaudin 1998). Furthermore, shelf organization may signal item attractiveness and steer purchase decisions; items that receive more shelf space than other alternatives are thought to be more successful and hence more attractive (Eisend 2014). Thus, without dismissing the existence of fully-informed influences on the decision making process of where and what to shop/eat (e.g. price or proximity considerations), it may be fruitful to take some distance with the assumption of fully conscious food choices, and consider also the complementary influences that occur outside of conscious awareness (Dijksterhuis, Smith et al. 2005; Cohen and Farley 2008). In light of these elements, we may logically question whether the foodscape may unconsciously influence the decision to patronize a healthy place rather than a less-healthy one (and inversely).

Empirical research in very recent years has shown that the relative density of healthy and unhealthy food outlets around home is more strongly related to the healthfulness of dietary behaviours than absolute densities of either healthy or unhealthy outlets taken separately (Mason, Bentley et al. 2013). Overall, the higher the proportion of healthy stores, the higher fruit and vegetable purchases and intake (Mason, Bentley et al. 2013), the better the overall quality of diet (Mercille, Richard et al. 2012), and the lower the consumption of fast-food and soda (Babey, Wolstein et al. 2011). This invites the question of whether the extent to which the relative densities of healthy and unhealthy food outlets in individuals’ living places may signal outlets’ popularity and impact food purchase behaviours. Yet, the use and usefulness of relative densities of healthy and unhealthy outlets requires both better conceptual integration and more empirical evidence. This thesis attempts to fill this gap.

26

1.4. Thesis plan

The next chapter (Chapter 2) is a literature review of how the central concept of access to the foodscape has commonly been approached in public health nutrition. It concludes that there is a need to put in perspective and better articulate the various influences, conscious and less conscious, that push individuals to opt for a healthy or a less healthy food outlet when the foodscape offers multiple alternatives to choose from. Chapter 3 (Article # 1) proposes a novel conceptualisation of access to the foodscape. Specifically, it upholds the original idea that the relative distributions of healthy and unhealthy food outlets drives a normative message about where and what to buy/eat. Chapter 4 introduces two case studies directly inspired from our conceptual proposal. They consist in exploring the association between relative densities of healthy and unhealthy food outlets and fruit and vegetable intake. Chapter 4 includes an explanatory statement and a description of the research objective, research questions, and methods employed to answer them. Drawing on multiple secondary datasets pertaining to adult residents of five large Canadian cities, chapter 5 examines the association between the percentage of healthy outlets both in the residential (Article # 2) and in the non-residential (Article # 3) environments and fruit and vegetable intake. Finally, Chapter 6. and 7. respectively discuss the findings, identify the potential impact and limitations of this research, and conclude.

28

2.1. The ‘slippery’ notion of access

2.1.1. Distinguishing real from potential access

Access is a complex concept lacking a clear and consensual definition (Penchansky and Thomas 1981). It has been indifferently referred to as a verb relating to the act of using a system, and as a noun referring to the potential for a system to be used (as in ‘accessibility’) (Guagliardo 2004). Recent literature on foodscape has usefully distinguished real (or realized or actualised (Guagliardo 2004)) from potential access (Zenk, Thatcher et al. 2014). On one hand, real access refers to the action of walking into a store or a restaurant to actually buy food or eat, and is directly measured by observing or surveying individuals’ behaviours. On the other hand, potential access refers to the potential for a food resource to be used and is determined by assessing whether the conditions for using that resource are met. It implies to identify the factors enabling or restricting the use of an outlet, and disentangle the mechanisms explaining how individuals use the foodscape.

From a public health nutrition perspective, it is not so much where people actually go for food shopping, as the factors that shape where they shop for food which is meaningful (Chaix, Meline et al. 2013; Zenk, Thatcher et al. 2014). At a time when guidance for creating health-supportive food environments is lacking, identifying the factors which facilitate or restrict the use of healthy and unhealthy food outlets represents a promising avenue for research and policies (Story, Kaphingst et al. 2008).

N.B.: Because this thesis will focus on potential access, from now on and until the end of the document ‘potential access’ will be simply referred to as ‘access’ for ease of reading.

29

Actual use will explicitly be referred to using the full expression ‘real access’ to avoid confusion.

2.1.2. Earliest conceptual foundations of access

Earliest conceptual foundations of access inspired by ‘gravity models’ have drawn on the fundamental assumption that interest for a given facility (i.e. food outlet) declines with distance from home, especially due to ‘frictions’ of time and transportation costs (Pacione 1974; Brown 1989). Doing so, consumers have been assumed to use the nearest places from home that offer the required goods or service (i.e. foods). This perspective led a wide range of studies to approach the question of access to the foodscape exclusively from a spatial accessibility perspective (Charreire, Casey et al. 2010; Caspi, Sorensen et al. 2012). They were motivated by the concern that individuals may opt for unhealthy food outlets for the simple reason that this outlet type was more readily accessible in the close vicinity of home than more distant healthy resources. Accordingly, various methods, subjective or objective, have been adopted to assess the degree of spatial accessibility to either healthy or unhealthy food outlets (McKinnon, Reedy et al. 2009). With regard to subjective measures, researchers have drawn on individual perceptions of accessibility (Pearson, Russell et al. 2005; Caldwell, Miller Kobayashi et al. 2009; Sharkey, Johnson et al. 2010; Williams, Ball et al. 2010; Gustafson, Sharkey et al. 2011; Sohi, Bell et al. 2014), for instance, by asking participants whether they perceived certain types of food outlets to be within walking distance of their homes (Caspi, Kawachi et al. 2012). Studies using objective measures have mostly relied on proximity (i.e. distance) or density (i.e. number in a bounded area), using Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Proximity has variably been measured using travel time (Pearce, Witten et al. 2006; Burns and Inglis 2007; Pearce, Blakely et al. 2007; Jiao, Moudon et al. 2012) or metric distance to food stores - either

30

Euclidean (Laraia, Siega-Riz et al. 2004; Winkler, Turrell et al. 2006; Apparicio, Cloutier et al. 2007; Wang, Kim et al. 2007; Bodor, Rose et al. 2008; Murakami, Sasaki et al. 2009; Michimi and Wimberly 2010; Izumi, Zenk et al. 2011), Manhattan (Zenk, Schulz et al. 2005) or street-network based (Donkin, Dowler et al. 2000; Clarke, Eyre et al. 2002; Pearson, Russell et al. 2005; O'Dwyer and Coveney 2006; Jago, Baranowski et al. 2007; Liu, Wilson et al. 2007; Larsen and Gilliland 2008; Sharkey and Horel 2008; Smoyer-Tomic, Spence et al. 2008; Timperio, Ball et al. 2008; Pearce, Hiscock et al. 2009; Sharkey, Johnson et al. 2010; Thornton, Crawford et al. 2010; Williams, Ball et al. 2010; Gustafson, Sharkey et al. 2011; Caspi, Kawachi et al. 2012; Sharkey, Dean et al. 2013; Wedick, Ma et al. 2015). Density has usually referred to the number of food outlets within a certain perimeter from home. Some have relied on administrative boundaries such as census tract enclosing home (Morland, Wing et al. 2002). Others have used home-centered units of aggregation such as circular buffers (Laraia, Siega-Riz et al. 2004; Jeffery, Baxter et al. 2006; Winkler, Turrell et al. 2006; Wang, Kim et al. 2007; Bodor, Rose et al. 2008) or street-network buffers (Burdette and Whitaker 2004; Jago, Baranowski et al. 2007; Liu, Wilson et al. 2007; Smoyer-Tomic, Spence et al. 2008; Timperio, Ball et al. 2008; Paquet, Daniel et al. 2010; Thornton, Crawford et al. 2010; Williams, Ball et al. 2010) with a radius chosen to match the supposed distance individuals are ready to travel to get their food. Yet, in absence of consensus on what that distance is, various values roughly ranging from 100 meters to 5 miles have been used (Charreire, Casey et al. 2010; Caspi, Sorensen et al. 2012). In short, finding appropriate and consistent criteria for defining geographic boundaries of spatial accessibility has proven challenging (Charreire, Casey et al. 2010).

Overall, the relationship between dietary behaviour and spatial accessibility to various food outlets has lacked consistent evidence both with objective and perceived measures (Charreire, Casey et al. 2010; Caspi, Sorensen et al. 2012). Whereas increased spatial accessibility to healthy (Morland, Wing et al. 2002; Laraia, Siega-Riz et al. 2004; Rose and Richards 2004; Zenk, Schulz et al. 2005; Caldwell, Miller Kobayashi et al. 2009;

31

Michimi and Wimberly 2010) and unhealthy (Satia, Galanko et al. 2004; Timperio, Ball et al. 2008; Moore, Diez Roux et al. 2009; Gustafson, Sharkey et al. 2011) food sources have been associated with diets of better and lower nutritional quality respectively, many studies have found no associations (Burdette and Whitaker 2004; Rose and Richards 2004; Cummins, Petticrew et al. 2005; Simmons, McKenzie et al. 2005; Jeffery, Baxter et al. 2006; Bodor, Rose et al. 2008; Pearce, Hiscock et al. 2008; Turrell and Giskes 2008; Pearce, Hiscock et al. 2009; Thornton, Bentley et al. 2009; Jaime, Duran et al. 2011). Furthermore, the few studies that have investigated interventions bringing healthy food sources (e.g. supermarkets or grocery stores) in underserved residential areas did not provide convincing evidence that increased local availability of healthy food outlets would alter dietary behaviours of local residents (Cummins, Petticrew et al. 2005; Cummins, Flint et al. 2014).

Despite a lack of consistent evidence between spatial accessibility to food sources and dietary behaviour, it would be premature and potentially misleading to conclude that altering retail distribution may not impact health. Instead, the studies carried out to date have provided justification for a reinforced investigation of how and how much the distribution and type of food outlets shape dietary behaviours and health. Beyond the practical necessity for improved measurement of diet outcomes (Kirkpatrick, Reedy et al. 2014) and of exposure variables (Lytle 2009; McKinnon, Reedy et al. 2009; Burgoine, Alvanides et al. 2013), scholars have also called for an improved conceptualisation of access to the foodscape (Macintyre, Ellaway et al. 2002; Cummins, Curtis et al. 2007). Doing so requires to identify the elements of the foodscape that may influence dietary behaviours and the corresponding mechanisms (Entwisle 2007).

32

2.2. Is there only spatial accessibility in access?

In recent years, conceptual refinements of access have been driven by two considerations. First, individuals are mobile (Miller 2007) and do not systematically get their food in the vicinity of home (Day 1973; Inagami, Cohen et al. 2006; Hillier, Cannuscio et al. 2011; Kerr, Frank et al. 2012). As individuals do not always shop locally, other dimensions beyond home proximity should be accounted for when conceptualising access. Second, individuals do not experience the foodscape in a same way (Thompson, Cummins et al. 2013). A sound conceptualisation of access should therefore consider how both individual and environmental characteristics interrelate and create the conditions for use (Cummins, Curtis et al. 2007).

2.2.1. Individuals’ mobility or the stretching opportunities for food shopping

Individuals’ daily mobility has been growing, helped by the advent of transportation and information technologies (Miller 2007). Individuals travel on a daily basis through and beyond the invisible boundaries traditionally used by researchers to delineate units of aggregation and derive measures of access (Matthews 2010). Surely, movement across space is constrained by certain spatial boundaries, since individuals have to compose with their mobility potential (Shareck, Kestens et al. 2014), depending on both intrapersonal (e.g. physical disability) and structural (e.g. public transport availability) factors. The extent of daily mobilities is therefore subject to variation among populations. For instance worse-off (Hanson and Hanson 1981; Murakami and Young 1997; Clifton 2004), the elderly (Tacken and Rosenboom 1998; Inagami, Cohen et al. 2007; Lord, Després et al. 2011) and women (Hanson and Hanson 1980; Hanson and Hanson 1981; Hanson and Johnston 1985; Frändberg and Vilhelmson 2011) have been

33

reported to travel shorter distances on a daily basis than their counterparts. Yet, overall, access may not be as confined and bounded as we have tended to feature it (Matthews 2010). Defining access exclusively as a measure of spatial accessibility to local resources is misleading and may explain why research standing behind that conceptual position has shown discrepancies (Chaix, Merlo et al. 2009; Perchoux, Chaix et al. 2013).

As people move throughout the city, additional opportunities to get food present to themselves, mostly because of cumulative exposure (Kestens, Lebel et al. 2010), but also because densities of food outlets experienced away from home tend to be higher compared to at home (Kestens, Lebel et al. 2010; Burgoine and Monsivais 2013; Crawford, Jilcott Pitts et al. 2014; Clary and Kestens Unpublished results). As a result, daily mobility tends to considerably stretch the range of food shopping possibilities (Widener, Farber et al. 2013). Empirical evidence attests that individuals actually use food shopping opportunities located far beyond the home vicinity (Day 1973; Inagami, Cohen et al. 2006; Hillier, Cannuscio et al. 2011; Kerr, Frank et al. 2012). They do not necessarily do so in order to escape a scarcity of supply in the vicinity of home (Day 1973; Cummins, Petticrew et al. 2005; Drewnowski, Aggarwal et al. 2012; Cannuscio, Tappe et al. 2013). Instead, they bypass closer food outlets for more distant but more desirable destinations. Even worse-off individuals, presumed to be limited in their mobility potential (Shareck, Frohlich et al. 2014), are actually reported to take advantage of food stores located far beyond their residential neighbourhood (Hillier, Cannuscio et al. 2011; Aggarwal, Cook et al. 2014). Cannuscio et al. highlighted that distance traveled to reach the primary shopping place did not differ significantly by socioeconomic status (Cannuscio, Tappe et al. 2013). Overall, consumers do not seem to strictly minimize traveled distances (Dellaert, Arentze et al. 1998).

34

2.2.2. Proximity… and the many other outlet characteristics influencing food outlet choice

When making decisions about where to buy food, consumers evaluate the interest of food sources on complementary characteristics beyond location. There is evidence that food store choice is made regarding financial considerations (Ayala, Mueller et al. 2005; Krukowski, Sparks et al. 2013; Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014). For instance, Drewnowski et al. have shown that the nearest food stores from home tend to be bypassed for more distant but cheaper options (Drewnowski, Aggarwal et al. 2012). Consistent with these findings, supermarkets have been reported as a privileged outlet for primary food shopping at the expense of closer places (Rose and Richards 2004; White, Bunting et al. 2004; Ayala, Mueller et al. 2005; D'Angelo, Suratkar et al. 2011; Cannuscio, Tappe et al. 2013), especially due to their relatively low prices (Pacione 1974; Chung and Myers 1999; White, Bunting et al. 2004; Rose, Bodor et al. 2009). Given the essential nature of feeding and the frequency with which individuals need to eat, food represents an unescapable and considerable expenditure for families. This may help understand why travel costs may be sacrificed to the interest of more distant, but more financially profitable options.

Several studies have further demonstrated that factors pertaining to the convenience of a store were also relevant to store selection. For instance, facilities to complete shopping quickly, store opening hours, and presence of a parking area have all been reported as influencing factors for deciding where to shop (Ayala, Mueller et al. 2005; Helgesen and Nesset 2010; Krukowski, Sparks et al. 2013).

Now, food shopping is more than an instrumental activity for maintenance of the household. Cultural and symbolic aspects have further been shown to complementarily influence the decision about where to shop for food (Day 1973). For instance, individuals have reported to selectively shop at stores that aligned with their self-perceived socioeconomic and cultural status, that is where they had positive

35

interactions with customers and personnel (Ayala, Mueller et al. 2005; Cannuscio, Weiss et al. 2010; Helgesen and Nesset 2010; Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014) and where culturally congruent foods were available (Wang, MacLeod et al. 2007; Cannuscio, Tappe et al. 2013; Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014). The search for social interactions may also sometimes outweigh the primary purpose of food purchasing (Cannuscio, Weiss et al. 2010).

Hence, in recent years, conceptual refinements of access have increasingly recognised the multiple influences that impact the way individual use the foodscape (Cummins, Curtis et al. 2007; Story, Kaphingst et al. 2008).

2.2.3. The multidimensional concept of access

Individuals tend to use the various resources provided by their surroundings differently, because they have different capacities and motivations to do so (Entwisle 2007; Frohlich and Potvin 2008). For instance, a person may judge the delicatessen store next door his/her house inaccessible, as prices may be considered too high relatively to his/her income, and therefore shop at the corner store further down the street which proposes cheaper options. Yet, this very same delicatessen shop may be frequently used by a wealthier neighbour whose generous pension makes financial considerations less relevant. People are selective with their foodscape in a manner that tend to accommodate their means, constraints and preferences (Entwisle 2007). Consequently, it is neither the location, nor the price, the type of service available, or the atmosphere

in itself that will help designate a food store as a potential candidate for use. Instead, it

is a combination of all those characteristics in relation to individuals’ ability and desire to accommodate to them (Cummins, Curtis et al. 2007). Individuals’ trade-off between value-for-money and distance, or between convenience and friendliness of staff, for

36

example, is likely to vary (Smith and Sanchez 2003). In sum, both individual and foodscape characteristics interrelate to create the conditions of use.

Borrowing from Penchansky and Thomas’ work on access to healthcare (Penchansky and Thomas 1981), most recent conceptualisations of access have built upon five dimensions of ‘fit’ between individuals’ capacity and predispositions to use the foodscape, and the actual characteristics of food outlets. These five dimensions, known as availability, spatial accessibility, affordability, accommodation, and acceptability (e.g. (Charreire, Casey et al. 2010; Caspi, Sorensen et al. 2012; Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014)), have been transposed from Penchansky and Thomas’ definition (Penchansky and Thomas 1981) (with a few “adjustments” discussed further in this paragraph). 1)

Availability is commonly referred to as the actual existence of the outlet type of

interest, and is mainly operationalised as the objective or perceived number of this outlet type within a certain perimeter (Morland, Wing et al. 2002; Jeffery, Baxter et al. 2006; Bodor, Rose et al. 2008; Turrell and Giskes 2008; Moore, Diez Roux et al. 2009; Murakami, Sasaki et al. 2009; Zenk, Lachance et al. 2009; Williams, Ball et al. 2010; Gustafson, Sharkey et al. 2011; Jennings, Welch et al. 2011). 2) Spatial accessibility usually represents the relationship between the location of food resources and individuals’ ability to reach that location, accounting for transportation resources and travel time, distance and cost. It has mostly been assessed in terms of distance perceived (Inglis, Ball et al. 2008) or objectively measured (Laraia, Siega-Riz et al. 2004; Pearce, Hiscock et al. 2008; Turrell and Giskes 2008; Pearce, Hiscock et al. 2009; Zenk, Lachance et al. 2009; Michimi and Wimberly 2010; Sharkey, Johnson et al. 2010; Williams, Ball et al. 2010; Gustafson, Sharkey et al. 2011). 3) Affordability is the relationship between prices and the individuals' ability to pay. It has been operationalised, for instance, as participants’ perceptions of produce affordability (Zenk, Schulz et al. 2005; Inglis, Ball et al. 2008; Sharkey, Johnson et al. 2010; Williams, Ball et al. 2010) or store auditors’ accounts of food prices (Pearson, Russell et al. 2005; Zenk, Lachance et al. 2009). 4) Accommodation represents the relationship between

37

the manner in which the food resources are organized to accept individuals and individuals' ability to accommodate to these factors; it has variously designated hours of operation (Thornton, Crawford et al. 2010; Chen and Clark 2013), car-/bike-park and walk-in facilities (Widener, Metcalf et al. 2011; Chen and Clark 2013), as well as acceptance of informal credit payment (Horowitz, Colson et al. 2004). 5) Acceptability refers to one’s feeling of socio-cultural harmony (Day 1973). This concept builds on the idea that food places provide the structuring context for social relations (Feagan 2007) and has been operationalised as a measure of socio-cultural harmony both regarding the staff (Cannuscio, Weiss et al. 2010), the customers (Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014) and the products sold (Wang, MacLeod et al. 2007; Cannuscio, Hillier et al. 2014). In practice, empirical studies have assessed the extent to which one type of outlet (either healthy or unhealthy) was meeting the condition for access with regard to one or a few dimensions enumerated above (Charreire, Casey et al. 2010; Caspi, Sorensen et al. 2012). Unhealthy outlet types of interest have generally included fast-food restaurants (Morland, Wing et al. 2002; Burdette and Whitaker 2004; Baker, Schootman et al. 2006; Jeffery, Baxter et al. 2006; Burns and Inglis 2007; Liu, Wilson et al. 2007; Smoyer-Tomic, Spence et al. 2008; Timperio, Ball et al. 2008; Turrell and Giskes 2008; Moore, Diez Roux et al. 2009; Pearce, Hiscock et al. 2009; Thornton, Bentley et al. 2009; Paquet, Daniel et al. 2010; Jennings, Welch et al. 2011) and convenience stores (Morland, Wing et al. 2002; Laraia, Siega-Riz et al. 2004; Liu, Wilson et al. 2007; Pearce, Hiscock et al. 2008; Timperio, Ball et al. 2008; Zenk, Lachance et al. 2009; Izumi, Zenk et al. 2011), while healthy ones have mainly included supermarkets (Donkin, Dowler et al. 2000; Morland, Wing et al. 2002; Laraia, Siega-Riz et al. 2004; Rose and Richards 2004; Pearson, Russell et al. 2005; Zenk, Schulz et al. 2005; Baker, Schootman et al. 2006; O'Dwyer and Coveney 2006; Apparicio, Cloutier et al. 2007; Burns and Inglis 2007; Liu, Wilson et al. 2007; Bodor, Rose et al. 2008; Larsen and Gilliland 2008; Moore, Diez Roux et al. 2008; Moore, Diez Roux et al. 2008; Pearce, Hiscock et al. 2008; Smoyer-Tomic, Spence et al. 2008; Timperio, Ball et al. 2008; Zenk, Lachance et al. 2009; Michimi and

38

Wimberly 2010; Sharkey, Johnson et al. 2010; Thornton, Crawford et al. 2010; Williams, Ball et al. 2010; Jennings, Welch et al. 2011), grocery stores (Morland, Wing et al. 2002; Laraia, Siega-Riz et al. 2004; Zenk, Lachance et al. 2009; Gustafson, Sharkey et al. 2011; Izumi, Zenk et al. 2011), and fruit and vegetable stores/markets (Timperio, Ball et al. 2008; Williams, Ball et al. 2010; Izumi, Zenk et al. 2011; Jennings, Welch et al. 2011). However, the choice to look at one outlet type over another has overall lacked sound justification.

In their original work on healthcare access, Penchansky and Thomas defined availability strictly as “the relationship of the volume and type of existing services (and resources) to the clients' volume and types of needs”. This notion of needs appears central to their definition of availability - and, in turn, access - as it provides guidance on what

resources should be looked at when access concerns are raised. Healthcare resources to

which access should be assessed are those which people need. Yet, “access to what?” is a question that has been rather absent from the literature on foodscape access. This may explain why the choice to look at one given food outlet rather than another one seems rather arbitrary. In sum, the public health nutrition field has recently been valuably marked by a shift from a purely geography-driven definition of foodscape access to a more inclusive and comprehensive approach. Yet, we suggest that there is still room for improvement in our conceptualisation of access, especially regarding what resources should be looked at when foodscape access is put in relation to dietary behaviors, and the reasons why.

2.3. Access to healthy outlets, to unhealthy outlets or to both? The disregarded question of alternatives

With regard to the healthcare system, the linkage between a given health disorder, the corresponding need(s) and the required resource(s) is somehow straightforward,

39

because it is dictated by the health system itself. For instance, nobody would reasonably contest that an individual suffering with eye disorders (initial concern) is in need for an eye examination/care (corresponding need), and that eye services represent the most appropriate resource (required resource) to use in order to tackle that issue. Thus, if we meant to assess how much the healthcare system has a positive or detrimental impact on an individual suffering from eye disorders, the focus would be on eye services, and studies would, in turn, assess whether eye services were spatially accessible, affordable, convenient and acceptable.

However, unlike the healthcare system, the foodscape is an exclusively market-guided system whose economic rules are established in the primary aim of its own economic viability (Evans, Bridson et al. 2008), not consumers’ health. It encloses both healthier (e.g. fruit and vegetable stores) and unhealthier (e.g. fast-food restaurants) food sources. Thus, depending on the selected options, individuals convert their need for food into either healthy or less healthy behaviours. Assuming that individuals tend to ‘maximise’ health benefits associated with consumption of food – or, put differently, assuming that food choices are driven by a need for healthy food, then, we might expect healthy resources to be used when accessible. Under that perspective where the default choice is presumed to be a healthy one, questioning foodscape influences on dietary behaviors could be restricted to assessing access to healthy food sources. And following along the same lines, an environment offering at least one spatially accessible, affordable, convenient and acceptable healthy food outlet could be deemed health-promoting, regardless of the access the environment may concomitantly offer to unhealthy outlets. Yet, there is evidence that individuals do not use unhealthy food sources for the mere reason that healthier options are non-accessible (Kubik, Lytle et al. 2003; Fox, Gordon et al. 2009; Cohen, Sturm et al. 2010; Yeh, Matsumori et al. 2010). That is, the ‘need for healthy food’ decreed by health authorities is a public health construct more than a universally accepted reality.

40

This statement has important consequences on the way access should be conceptualised. First, it appears misleading to stand behind the position that healthy dietary behaviours are constrained exclusively by how accessible healthy resources are ‒ and inversely that unhealthy dietary behaviours are constrained exclusively by how accessible unhealthy resources are. Rather, this invites to better considering what the foodscape has to offer as a whole. Second, for the field to move forward, it appears that a sound conceptualisation of access should better account for the various influences which push individuals to opt for a healthy food outlet or a less-healthy alternative when in a context of multiple, healthy and less healthy, choices. This led us to develop a novel conceptualisation of access to the foodscape. This conceptual proposal is presented in the following chapter.