Disponibleenlignesur

ScienceDirect

www.sciencedirect.comNeuropsychiatriedel’enfanceetdel’adolescence62(2014)477–488

Original

article

Early

deprivation

as

a

risk

factor

for

narcissistic

identity

pathologies

in

adolescence

with

regard

to

international

adoption

La

déprivation

affective

comme

facteur

de

risque

pour

les

pathologies

narcissiques

identitaires

chez

l’adolescent

adopté

D.

Vandepoel

,

I.

Roskam

∗,

S.-M.

Passone

,

M.

Stievenart

Psychologicalsciencesresearchinstitute,CatholicuniversityofLouvain,10,placeduCardinal-Mercier,1348Louvain-la-Neuve,Belgium

Abstract

Thecurrentstudyisapsychoanalyticreadingoftheclinicalmaterialarisingfromongoingdevelopmentalresearchintointernationaladoption withintheframeworkoftheAttachmentAdoptionResearchNetwork(AAARN).Theprimaryobjectiveofthestudyistoverifywhethertheseverity ofdeprivationexperiencedpreadoptionisariskfactorfornarcissisticidentitypathologiesinadolescencewithregardtointernationaladoption. Agroundedtheoryapproachisusedtoidentifyasetofqualitativevariables,whicharelaterquantitativelyassessed.Thefindingsarediscussed intermsofbothqualitativeandquantitativeresultsandsuggestthegreaterpresenceofchronicsomatictroublesandobservablesignsofprimary traumaintheadoptionpopulationcomparedtothecontrolgroup.Futureareasforresearcharesuggestedintheconclusion.

©2014ElsevierMassonSAS.Allrightsreserved.

Keywords:Primarytrauma;Narcissisticidentitypathologies;Somatictrouble;Adolescence;Internationaladoption

Résumé

Laprésenteétudeconsisteenunelecturepsychanalytiqued’unmatérielcliniquecollectédanslecadred’uneétudedéveloppementaleportant surl’adoptioninternationale:l’AttachmentAdoptionResearchNetwork(AAARN).Sonobjectifprincipalestdedéterminersilasévéritéde ladéprivationexpérimentéeavantl’adoptionconstitueunfacteurderisquepourlespathologiesnarcissiquesidentitairesàl’adolescence.Une approchethéoriquementfondéeestutiliséeenvued’identifierunensembledevariablesqualitativesquiseront,dansundeuxièmetemps,évaluées demanièrequantitative.Lesrésultatssontdiscutésqualitativementetquantitativement;ilssuggèrentlaprésenceaccruedetroublessomatiques chroniques,ainsiquedesignesobservablesd’untraumatismeprimaireparcomparaisonavecungrouped’adolescentscontrôle.Despistesde recherchesfuturessontsuggéréesdanslaconclusiondecettecontribution.

©2014ElsevierMassonSAS.Tousdroitsréservés.

Motsclés:Traumatismeprimaire;Pathologiesnarcissiquesidentitaires;Troublesomatique;Adolescence;Adoptioninternationale

1. Introduction

Itisincreasinglyacceptednowadaysthataprimarysource ofemergingnarcissisticidentitypathologiesisearlyrelational trauma[1–6].Ifthisisthecase,shouldnotseverityofdeprivation

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:isabelle.roskam@uclouvain.be(I.Roskam).

experiencedpreadoptionbeariskfactorfornarcissisticidentity pathologies inadolescencewithregard tointernational adop-tion?

Despitecontrastingempiricalresearchresultsregardingthe long-term effects of international adoption on mental health [7–11],largecohortstudiesevidencethatadolescentsandyoung adultswhohavebeenadoptedininfancyareoverallmoreatrisk ofseverementalproblems,includingsuicideorattempted sui-cide,thantheirnon-adoptedpeers[12,13].Suchhigherriskfor http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neurenf.2014.09.002

suicideisconsistentwiththeidentitydisordersoftenobserved ininfantpsychiatry inthe caseof adolescentsinternationally adopted in infancy [14].What is also clear is that length of preadoptiontimeandseverityofcaregivingdeprivationemerge astwopredictingfactorsofdelaysinthedevelopmentof neuro-logicalandage-levelmotorskills,andthatthesimpleenrichment oftheadopted child’senvironmentfollowingadoptionproves insufficienttorepairsuchdamagebeyondcertaincriticalages orsensitiveperiods[10,15–18].Thesesensitiveperiodsand cut-offagesdifferdependingontheinstitutionandcountryoforigin accordingtotheseverityofdeprivationtowhichthechildhas beenexposed[19].

International adoption is obviously an extreme early life situation,characterizedbyintrapsychicandintersubjective dis-continuities, all of them potentially traumatic, as well as by exposure to different culture/language (and group symbolic contents)andrace/ethnicity.Itmaythereforerepresentalimiting caseinthemathematicalsense, towhichitisworthapplying theoreticalconceptsregardingtheeffectoftraumaonearly cog-nitiveandemotionaldevelopment.Thecurrentresearchdraws ontwopsychoanalyticalmodelsregardingtheeffectoftrauma on early cognitive and emotional development: Bion’s alpha functionandRoussillon’sprimarytrauma.Theirmainconcepts areshortlyreviewedhere,togetherwiththeir consistencyand reliabilityinregardtothelimitingcaseofinternationaladoption, inthelightofthefindingsofrecentneurobiologicalresearchon earlyrelationaltrauma.

1.1. Alphafunctionandsomatization

Bothattachmenttheoryandpsychoanalyticalmodelsagree ontheessentialroleplayedbythecaregiver’sresponsetothe child’sexpressionof need [20].Bion consideredthe endoge-nous andexogenous perceptionsof a young childin distress aspreliminaryformsofthoughtresultingfromanuncompleted symbolizationprocess.Themalleabilityoftheobject’sresponse expressedbyBion’sconceptofmaternalreverieensures,onthe partofthechild,thealphafunctionthattransformsperceptions into first representations,enabling thecompletion of primary symbolization.Itisakeyrequisiteforaseamlesstransitiontothe secondarysymbolizationinvolvedintheaffectiveandcognitive regulatingfunctionsoftheself[21–23].Thechildprogressively internalizes andstabilizes incontact with his or her primary caregivers, the alpha function, prompting the organization of theselfthroughtheprismofacontactbarrierconstructedfrom alpha elements designed to buffer contrasting experiences of the primaryobject’s level of attention(absence/presence, sat-isfaction/frustration,good/badexperiences)andleadingtothe integrationofambivalence.Asaresult,itbecomespossiblefor the childtoovercome the depressive positionin thesense of Klein [24]whichoccurs mainlyinthe second six months of lifewiththedisillusionthatfollowsthelossofinfantfantasies ofomnipotentcontrol,butwhichisrevisitedthroughouta per-son’slifewheneveralossisexperienced[25].Conversely,the experienceofachildwhoisdramaticallyand/orlong-lastingly deprivedofmaternalreverie,andhence,unabletotransform per-ceptivetracesintoasymbolizedmaterial,isoneofterror[22],

andstabilizationofthealphafunctioniscompromised.Laterin thecourseofdevelopment,thesubjectdeprivedofastabilized alphafunctionisalsomoreatriskofunloadingexcessive excita-tionbackontothesoma.Theimmunesystemwillhavedifficulty copingwiththisload,andthispavesthewayforchronicsomatic troubles.Theagesatadoptionof theadolescentsstudiedhere andthedefiningoftheseagegroupsarethereforeexpectedtobe afirstcriticaldesignconsiderationinordertoassessthealpha functiondegreeofinternalizinginadolescence.

1.2. Primarytraumaandstateofagony

Roussillon[26]offersinthesamelineofinfluenceasBiona psychoanalyticalmodelinthreestageswhichincludes dimen-sionsofcaregivingdeprivationseverityanddurationasameans ofdescribingearlyandultra-earlytraumasassociatedwiththe terrorexperiencegeneratedbythefailureofthematernalreverie. The model describes how a situation that is onlypotentially traumatic becomes increasingly traumatic depending on how theenvironmentrespondstothechild’sdistress.Failureatthe first stage, inwhichthe child attemptstodrawuponinternal mentalresourcestobindordischargetheinfluxof excitations leadstoasecondstagecharacterizedbyhelplessness,inwhich thechildtriestosetupanarcissisticcontractwiththeprimary object inordertoreduce anxiety.The contract is narcissistic becauseitistaintedbythecaregiver’sinsufficientlymalleable response,andinvolvesapricethatthechildhastopay.Ifsetting upanarcissisticcontractfailsbecausetheobject’sresponseis too unsatisfactoryor becausethepricetopayistoohigh, the overwhelmingexcitationbreaksthroughthechild’sprotective shield, exertingamentalviolencethat mobilizesan impotent rageandfurtherexacerbatesthestateofhelplessness.Thechild triestogetridofthisragebyprojectingitontheobject.This violenceiscorrelatedwithasenseof primaryguilt,very dis-tinctfromthesecondaryguiltassociatedwithovercomingthe Kleiniandepressiveposition.Thethirdstageofthemodel hap-penswhenthestateofhelplessnessbecomesunbearableinits durationandescalatestheprimarytraumaticsituationintoastate ofagonythatcanproducetheterrortheorizedbyBion[23].This traumatic statebeyondhelplessnessandhope(state ofagony) inducesanexistentialdespair.AccordingtoRoussillon,the sub-jectpreferstofeelguiltyandresponsibleandthereforeincontrol for havingfailedtocopewithwhatheorshewasfacedwith, ratherthanfacingthesenseofhelplessnessassociatedwiththe agonizingexperience. Thus,thesubject fightstomaintainthe illusionofomnipotentcontrol,insteadofintegratingtheaspects ofambivalence.

1.3. Splittingandnarcissisticidentitypathologies

Incontrastwiththeobjectivistapproachthatdominates psy-chiatricclassificationsofnarcissisticdisturbances,Roussillon’s theoreticalapproachprovidesacomprehensiveapproachto psy-chologicalpain,byconsideringthesymptomasanexpression ofamentaldisorderdeterminedbytypesofanxieties,defense mechanismsandobjectrelationships.Roussillontheorizesthat inordertosurvivethestateofagony,thechildwithdrawsfrom

Table1

Mainandadditionaldefensemechanismsassociatedwithprimarytrauma.

Organizationofdefensemechanisms Consequences

Maindefensemechanismagainstexperienceofprimaryagony(primarytrauma):

Splitting

Compulsiontorepeat/splitofftendstoreturntoand reproducethetraumaticstateitself

Additionaldefensemechanismstocounterthereturnofsplitofftrauma Impoverishestheselfandthereforeleadstonarcissistic

identitypathologies;

Unrepresentedpartofthementalsystemgenerates excitationinexcess

Amputationofpartoftheselftomaintainarelationwiththeobjectandregressfrom stateofagonytostateofhelplessness

FalseSelf(partofthementalsystemisdedicatedtoprotectingthe(true)selfagainsta worldfelttobeunsafe)

Globalorganizationofthementallifethatseekstolimitobjectinvestmentandin generalallrelationshipsthatcanevoketheprimarytraumaareaanditsstateof helplessness

Otherssolutionsaimedatbindingexcessiveexcitationduetounrepresentedexperiences

Tiethankstosexualexcitation

Absorbbyplacingexcessiveemphasisonperceptionsandsensations

Trytosymbolizesecondarilywhatwasnotsuccessfullysymbolizedattheprimary stageusingdelirium(orthe“return”oftheperceptivememorytrace)

theprimarytraumaticexperience inordertostopfeeling,and this withdrawal “beyond the self” is described as a form of splitting.Theparadoxisthattheselfsplitsfromanexperience thatwasfeltandthatthereforeproducedlastingmemorytraces butdidnotgainarepresentation.Inthecourseoftheprimary symbolizationprocesswhichtransformsperceptions intofirst representations,afailureoccursthatpreventsitsfulfilmentand thereby,alsoinhibitsthefurtherprocessingofsecondary sym-bolization.Roussillon makestheassumption thatthe primary trauma thathas beensplitoff isgoverned bythe compulsion torepeat and tendsto returnto and reproduce the traumatic state itself. Additionalmechanisms appear beside the princi-palmechanismofsplittinginordertopreventthereturnofthe traumaticstate,andinthisway,animprovisedsolutionis struc-turedintoadefensivesyndrome.Table1providesanoverview ofthe mainandadditionaldefensemechanismsinvolved and howthoseimpoverishtheselfandthereforeleadtonarcissistic identitypathologies,theunrepresentedpartofthemental sys-temgeneratingexcitationinexcess.Roussillonregardssplitting asthekeymechanismbehindallformsofnarcissisticidentity pathologies,whilethedefensivesyndromeusedtopreventthe returnofthe splitoffprimary trauma definesthe formof the disorder [27]. Two clinical illustrations of how splitting and defenseagainstthe returnof thesplit offtrauma might oper-atewithadopteesaregivenintheworkofFagan[28]andHarf etal.[29].Suchamodeldrawsatheoreticallinkbetween pri-marytrauma,primaryviolenceandguilt,antisocialbehaviorand somaticandidentitydisorders.Itissupportedbyrecent neurobi-ologicalresearch[30–33].Itisalsoconsistentwiththerecurrent comorbidityobservedininfantpsychiatrybetweensomatization andpsychopathicpersonalitytraits[34].

1.3.1. Adoptionasanamplifieroffantasiesinadolescence

Adolescenceisasensitiveperiodwherealpha dysfunction mayberevealedevenmorestarkly, aspubertyinvolvesmajor neuralchangesintheaffectiveandexecutiveregionsofthebrain [35–37],andadolescentsdetachingfromtheirprimaryobjects

havetorelyincreasinglyontheirownresources,leavingtheir narcissisticvulnerabilityexposed[38].Suchreorganizationsare likelytoreactivatepotentialinfantileelementswhichwerestill pendingsecondarysymbolization(e.g.fantasies)onthepartnot onlyofadolescentsbutalsooftheirparents.Adoptionthusplays aroleasanamplifierofthecognitiveandaffective reorganiza-tionsspecifictopuberty,asadolescents’andparents’fantasies resonate with each other. Typical fantasies related to parent-ageandthesearchfororiginsinadolescencearemorecomplex for adopteesandafortiori forthosewhowereinternationally adopted than for their non-adopted peers, as the former deal withintrapsychicrepresentationsofbothadoptiveand biolog-icalparents,whoareoftencharacterizedbyoppositevalences. Theeffectsofpubertyandchronologicalagearenotclosely cor-relatedinearlyadolescence,especiallywithregardtoaffective braindevelopment[39].Thishighlightsthedifficultyof catego-rizinganddefiningagegroupsappropriately,andforthecurrent study,theagesoftheparticipantsstudiedandthelabelsusedfor differentagegroupsareexpectedtobeanothercriticaldesign consideration.

1.4. Objectiveandaddressedquestion

The question addressed in this study was “Is severity of deprivationexperiencedpreadoptionariskfactorfornarcissistic identity pathologies in adolescence with regard to interna-tionaladoption?”Inordertoaddressthisquestion,agrounded theory approach [40] was used to analyze the transcripts of semi-structuredinterviewsconducted with50adolescentsand their parents according to proven and validated variants of the AAI protocol, the Parental Development Interview [41] and Friends and Family Interview [42] respectively. Poten-tially suitable themes andcategories emergingduring coding wereclassifiedfirstlyastypesofanxiety,defensemechanism andobjectrelationship,secondlyaccordingtodegreeofalpha functioningandfinallyinrelationtoformsofnarcissistic iden-tity pathologies according to Roussillon’s classifications. All

subjects–bothadolescentsandparents–alsoself-administered theChildBehaviourCheckList[43].

2. Method

2.1. Participants

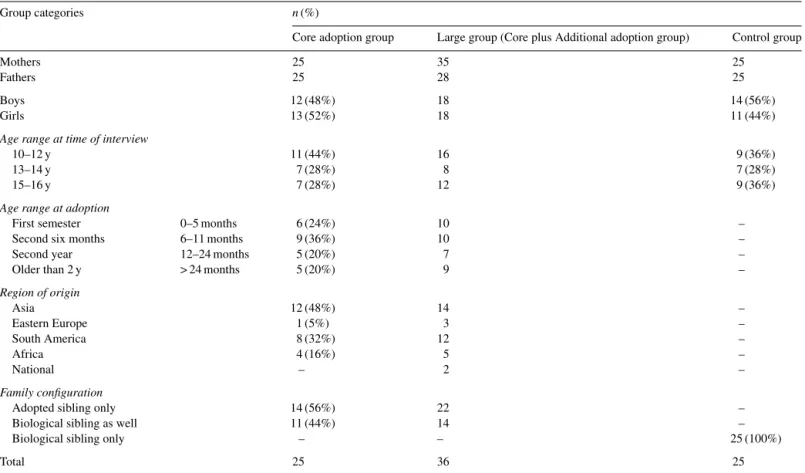

Theoriginaldevelopmentalresearchframedbythe Attach-ment Adoption Adolescents Research Network (AAARN) included 80Belgian adolescents and their parents, recruited usingaconveniencesamplingapproach,withthestudybeing advertisedinthelocalarea.

Casesforwhichdataweremissing,partialorextremewere discarded here.Asaresult,the current researchfocusesona coregroupoffiftyadolescents(25girls)aged10to16,ofwhom 25hadbeenadoptedinternationallyininfancyorinchildhood, andoftheirmothersandfathers.Theadolescentswereraisedin familieswithmid-to-highsocioeconomicstatus,i.e.theparents’ educationlevelwasmoderateorhighandtheyhadaccesstothe labormarket.

Table2summarizestheparticipants’distributionbygender, agegroupatthetimeofinterview,agegroupatthetimeof adop-tion,regionoforiginandadoptionfamilysiblings.Theagegroup designunderlyingthisdistributionisbasedoncriticalguidelines discussedintheintroduction.CBCLdatawereavailableforall subjects.Anadditionalgroupof11adoptedadolescentsinitially

discardedfromthestudy(e.g.becausethefather’sinterviewwas missing,orbecausetheadoptionwasnationalinsteadof inter-national)participatedinthefinaltestingofthemodeldeveloped duringtheresearch(seealsoTable2),inordertotestandvalidate thelimitsofthemodel.

2.2. Interviewsandtranscripts

TheParentDevelopmentInterview(PDI)isa59-item semi-structured clinical interviews designed to examine parents’ representations of their children, themselves as parents, their relationships with their children and their past relationships with their own parents. The Friends and Family Interview (FFI)isa36-item semi-structuredclinicalinterviewdesigned to examine adolescents’ representations of self, friends and family. Both are designed to assess internalworking models of relationshipsandareanautobiographical memorymeasure [42].Interviewswereconductedbypairsofextensivelytrained master’s students in developmental psychology,according to clearlydefinedprotocols[44,45].TheChildBehavior Check-list [43] is awidelyused parent andchild-reportmeasure of emotionalandbehavioralproblemsinyoungpeoplefromboth clinicalandresearchperspectives.ThederivedsixCBCL DSM-OrientedScaleswereconstructedthroughagreementinratings among22highlyexperiencedchildpsychiatristsand psycholo-gistsfrom16cultures.

Table2

Participants(adolescents).

Groupcategories n(%)

Coreadoptiongroup Largegroup(CoreplusAdditionaladoptiongroup) Controlgroup

Mothers 25 35 25

Fathers 25 28 25

Boys 12(48%) 18 14(56%)

Girls 13(52%) 18 11(44%)

Agerangeattimeofinterview

10–12y 11(44%) 16 9(36%)

13–14y 7(28%) 8 7(28%)

15–16y 7(28%) 12 9(36%)

Agerangeatadoption

Firstsemester 0–5months 6(24%) 10 –

Secondsixmonths 6–11months 9(36%) 10 –

Secondyear 12–24months 5(20%) 7 –

Olderthan2y >24months 5(20%) 9 –

Regionoforigin Asia 12(48%) 14 – EasternEurope 1(5%) 3 – SouthAmerica 8(32%) 12 – Africa 4(16%) 5 – National – 2 – Familyconfiguration

Adoptedsiblingonly 14(56%) 22 –

Biologicalsiblingaswell 11(44%) 14 –

Biologicalsiblingonly – – 25(100%)

Table3

Dataanalysisplan. Analysisplan

Thematicanalysis Stage-by-stage

process

Results

Deductivereasoning Opencoding, Axialcoding, Electivecoding Finalthemes, categoriesand theirdimensions andproperties Theoreticalsampling

Singlecasesorientedapproach Inductivereasoning

Primarytraumamodel Narcissisticidentitypathologies Variableorientedapproach

Quantitativeapproach Validation–Comparison

2.3. Dataanalysis

Table 3 gives an overview of the methodological back-bone that sustained the analysis. The data analysis process was non-linear, combining qualitative and quantitative pro-cedures, deductive andinductive reasoning, single cases and variableorientedapproaches.Theframeworkof psychoanalyt-icaltheory always prevailedand isa primary element of the researcher’ssubjectivity. From achronologicalpointof view, thefirstphasewaspurelyqualitative,usingthematicanalysis,a suitablemethodforexploringthelargedataset.Theprocessof dataanalysisoscillatedbackandforthbetweendata-drivenand theory-drivenapproaches;theemergingtheoreticalhypothesis ofprimarytraumaanticipatedinthetheoreticalintroductionof thispaper andits verificationswere heldinconstant interac-tionuntilthesaturationofcategories[46].Thefinaltheoretical items werelimited tothe themes andcategoriesvalidated by thedata.Thefinalresultsregardingadolescentscanbefoundin Table4.Thedevelopmentofreportsemergedfromthedetailed codingtablesandsummarizestheiroutcome;meanwhile, under-lyingideas were recorded in memos. The quantitative phase convertedaselectivesetofcategoriesintodichotomized varia-bles,computedtheminto SPSS21andcomparedtheirvalues totheavailableCBCLDSM-orientedScalesscoresthroughone wayANOVAtreatment,theChi2testandPearsoncorrelations.

2.3.1. Thematicanalysisandmeasurementtools

AssummarizedinTable3,thestage-by-stagedataanalysis processincludedopencoding,axialcodingandselective cod-ing.Itstartedwiththereadingofatheoreticallysampledsetof casesintheadoptiongroupandinthecontrolgroupinorderto saturategroupcategoriesusingasinglecaseapproach;itwas completedafter testingthe resulting modelwiththe enlarged groupofcases,includingtheadditionaldatasetofelevencases, usingavariableorientedapproach.Emergingthemesand cat-egoriesandrecurringdiscursivestructuresdrovethedesignof generationsofcodingtablesembeddingtheindividualaffective andcognitiveorganizationsidentifiedfor eachadolescentand parent.

2.3.2. Measures

Duringopencoding,textfragmentsfromparentsand adoles-cent’stranscriptswerecross-tabbedaccordingtotheirproperties

and dimensions (e.g. type of affect, representation, conflict, defensemechanism,objectrelationship)infirst-generation cod-ingtablesusingadata-drivenapproach.Thecodingtable,which was theoretically anchored at the beginning of the analysis, became simplified and focused once recurrent elements had appeared. During axial coding, the search for repeated inter-grouppatternsledtotheidentificationofdistinctcategories(e.g. projectionasdefensemechanism,dualrelationship).Selective codingwasarticulatedaroundtheresearchquestioninregardto narcissisticidentitypathologiesasanoutcomeofearlytrauma, duetoseverityof caregiving deprivation, firstlyroughly esti-matedbyageatadoption[19]andthenbygroup.Keycategories whichcouldembedgroupsofcategoriesweredefined. Insuffi-cientlyrepresentedcategorieswerediscarded.

Acodingjournalandcodingmemowerecreatedinorderto ensureinternalreliability.Coderreliability wasestablishedin twoways:

• during opencoding,threeinterviewsinbothtranscriptand videorecordingformweresubmittedtoagroupofclinicians workinginthechildcaresector.Thoseexpertscameoutinan independentgroupsessionwithallthecategoriesidentifiedby theresearcherintermsofmentalmechanismsanddiscovered noadditionalones;

• during selectivecoding, emerging key categories andtheir sub-hierarchywerelaterdiscussedandreviewedwithexperts innarcissisticidentitydisorderandinfantpsychopathology.

Duringaxialcoding,triangulationwasachievedbycollecting andcross-tabulatingdatafrombothparentsandadolescents.In ordertoestablishtheexternalvalidityofthequalitativemethod, thefindingsregardingonekeycategorywerequantitatively com-pared withthoseprovidedby theCBCL datacollection. The discussioncreatesadialoguebetweenqualitativeand quantita-tiveresults.

3. Results

3.1. Thematicanalysis

Table4 reports the finalcategories of anxietyanddefense mechanismsthatemergedfromthetriangulatedanalysisof par-ents’andadolescents’interviewtranscripts(derivingfromthe data-driven approachapplied during open andaxial coding). Their occurrence(overall) andfrequency(numberofadopted adolescentsfor whomthecategory wasspottedatleast once) arequantifiedfor boththecore(n=25)andthelarge(n=36) groups of adoptees. Categories are hierarchically organized according to the research question following the model pro-posedbyRoussillon[26](theory-drivenapproach)assignaling theexistenceofprimarytraumacorrelatedtolaternarcissistic identitydisorder(e.g.amputationofapartoftheself:refusalto thinkorlearnaboutorigins),defensebreakdown(e.g.returnof splitofftrauma:stateofagonytriggeredbycyclicevents)and othersolutionsaimedatbindingexcessiveexcitation(e.g. exag-gerated emphasison perceptions or sensations:the child can onlyassociatethe experience of separationwithsmells). The

Table4

Reportonthethematicanalysisforadolescentsadoptedininfancyorchildhood.

Keycategory Category Numberofcodes Numberofadolescents %adolescents

n* 25 36 25 36 25 36

Signsofprimary

Trauma Helplessness 24 36 16 25 64 69

Compliance 24 34 16 22 64 61

Shame 10 13 8 10 32 28

Stateofagonywhensick 10 14 10 15 40 42

Control 22 32 14 21 56 58

Rage 18 27 14 20 56 56

Withdrawal 39 51 17 25 68 69

Hyper-excitation 16 22 13 18 52 50

Somatizing Chronictroubles 17 25 13 19 52 53

Alphafunction

Functioning 23 30 14 18 56 50

Dysfunction 42 57 18 24 72 67

Otherssolutions

Sexualexcitation(inordertobindexcessiveenergy) 3 6 3 6 12 17 Petinorder(tointernalizethealphafunction) 10 12 9 12 36 33

Sounds 7 12 7 12 28 33

*Coregroup:n=25;Enlargedgroup(core+additionalset):n=36.

mappingschemabetweencategoriesandnarcissisticdefenses isillustratedinTable5.

3.1.1. Defensemechanismsamongadoptedadolescents

The content of information appeared at the outset to dif-fersubstantiallyaccordingtothe ageof theadolescentatthe momentofinterview.Thesharpanxietiesanddefense mecha-nismswereself-describinginthegroupof10–12yearsold,while falseselfandstrategiesfornegotiatingwithauthorityappeared moreclearlyintheoldergroups.

Overallhowever, adoptees seemedmore likelyto develop extremedefensemechanismsthantheirnon-adoptedpeers, dis-playing:

• strategiesofcontrol(56%),mainlyinordertopreserve free-domortomanagechange,asalltransitionsandseparations aredifficultandassociatedwithfear/stress;

• compliance(64%),e.g.over-attentivenesstoothers’mental state,tryingtoagree,psychologicalinsight,acuity,finesse; • withdrawal (68%),e.g. avoidingcontact when feeling sad,

self-representationaslazy;

• feelings of helplessness (64%), e.g. triggered by threat of disruptioninobjectrelationshipduetoconflict;

• episodesofrage(56%)triggeredbyfeelingofinjustice,e.g. alosswashiddenfromthechild,withprojectionanddenial offeelingsofanger(andfear).

Although helplessness is often denied,either by the ado-lescent (e.g.denialof loss)or bytheparents(e.g.trivializing daughter’s needs for attention), many adoptees, once over-whelmed,withdrawoutofreach inwhatparentsdescribed as theirownfantasyworld.Aremarkabletypeofobject relation-shipseemedtosubsistduringthiswithdrawal,asthe childor preadolescent indistressoftenfirstsoughtcontact withapet. Halfof the adoptedadolescents inthe 10–12-year-old group and36%overallreferredtoaspecialrelationshipwithafamiliar cat,rabbitorhorse.

Thecollapseofdefensesoftenappearedincorrelationwith thereturnofthestateofagony(e.g.triggeredbycyclicevents: birthdays, familycelebrationsorbyrelivingtheexperience of loss:losingafriend,associatedwithfantasyofdeath)andcould taketheformofsomatization(e.g.feelinglikedyingwhensick). Table5

Narcissisticdefensesyndromesandcategorymapping.

Thematicanalysis Narcissisticdefensesyndromes Defensebreakdown

Category Amputationofapart oftheself

Falseself Globalorganizing Othersolutions Defensebreakdown Stateofhelplessness e.g.Refusaltothink

orlearnaboutorigins

e.g.Triggeredby threatofdisruptionin objectrelationship (duetoconflict) e.g.Denialof feelings;Denialof loss

e.g.Returnofsplitofftrauma– stateofagonytriggeredby cyclicevents(birthdays,family celebrations)

Compliance Codes

Control Codes Codes

Rage Codes Codes

Withdrawal Codes Codes Codes Codes

The inputprovided bythe analysis of the 10- to12-year-old andtheir parentsevokes theexistence of the splitoff part of theadolescent’sselfthatsuddenlynearsthesurface,givingthe parentsthestrangefeelingthatthechildortheadolescentisatthe sametimethereandnotthereand“actualizingthestupor–the archaicterror”–thatwecanassumethechildonceexperienced andthatnowthreatenstherelationship.Suicideattemptsorrisks werementionedbytheparentsfor3adopteesand1biological child.Onlyinthe caseof thebiologicalchilddidthe mother associate the suicide attempt withher own brother’s suicide. Thisfrequency,despitebeingstatisticallyinsignificantwiththis smallsizesample,matchestheriskratioobtainedbyHjernand al.[12].

3.1.2. Otherobservedsolutionsaimedatbindingor dischargingexcessiveexcitation

Theotherobservedsolutionsare:

• contrastbetweenphysicalmaturity(e.g.earlysexualactivity asanattempttointegratetraumaticexperienceswhichhave notbeenworkedthroughbymeansofsexualexcitation)and affectiveimmaturity,withadelayinaffectiveandcognitive mentalizing(e.g.adopteesreportedtobeimmatureintermsof understandingandhencealsolearning:theyneedto“replay” dialogsinordertograspemotionsorreceiveattentionfrom othersinordertolearnconcepts);

• sensory perceptions are a first means of describing expe-riences of separation while memories are still missing. Soundsandmusicplayaroleinprovidinganexperienceof accordancewithothersbutalsohelpwiththinkingand con-ceptualizing,calmanxietyoropenupatransitionalspacefor encounterwithparentsandpeers[47];

• the sense of belonging offered by the group of peerswas anothersolution frequently usedby the adoptees(inyouth clubsandsportsteams).

3.1.3. Alphafunction

Ten to 12-year-old adoptees tended more than their non-adopted peers to have developed only one side of the ambivalence.Feelingsof sadness anddepressive feelings are oftenmentionedwhichrecallheretheearlydeprivation corre-latedwiththe primarystate of agony experiencesrather than theovercomingofthedepressiveposition.Amongadoptees,it seemedmorefrequentfortheambivalence(normallyresolved bytheovercomingoftheKleiniandepressiveposition)toextend largelybeyondnormalage.Itappearsonlytoberesolvedlater, withinthe15–16-year-oldgroup,whoseemedtointegrate con-trastingemotions.Adolescentsof10–12and13–14yearsofage were observed to more frequently verbalize how they strug-gledwith adysfunction of the alpha function withissues of absence/presence(e.g.excessiveattentiontoothers’presence), temporalitywhenfacedwithuncertainty,whichinducesstress andimpatience (e.g. timeis necessary to handle constraints, planningisanissue)andtransitionality(e.g.“allornothing” atti-tudeassociatedwithsleepproblemsandhyper-excitation;lack ofaccesstofeelings,ordifficultywithexpressingfeelings).As saidabove,calminganxiety(whichcanleadtotheinternalizing

ofthealphafunction)oftenseemedtobemediatedbyaclose relationshipwithapet.

Inordertoverifywhetherthecategoriesweremorespecific toadopteesthantonon-adoptedadolescents,theywere quan-tifiedandsystematicallymeasuredintheadoptionandcontrol groups,whereapplicableinrelationwithgroupdesignvariables (ageatadoptionandageatinterview)inordertorebutorconfirm theassumptionsthatemergedfromthethematicanalysis.Two keycategories,signsofprimarytrauma(embeddingtheextreme defensemechanismsobservedandpresumablyputinplaceto preventthereturnofthesplitoffprimarytrauma)andsomatic troubles(correlatedwithchronic/geneticdisease,andor asso-ciatedwithearlyinfancy illness) werecomputedinSPSS21. OnewayANOVAanalysisandChi2testswereperformedand verifiedfor:

• sample independence,equality ofvariancesandequalityof meansforthefirst;

• sampleindependenceandexpectedcountforthesecond.

3.2. Quantitativeanalysis 3.2.1. Variables

Categories taken into account as signsof primary trauma wererage,excessivecontrol–initspreventiveandanticipating function, compliance, withdrawal when upset or sad, hyper-excitationand feeling astate of agony whensick. The result isaqualitative dichotomousvariableassessedonthebasisof thetriangulatedinterviews,withatleasttwomainsignsof pri-marytraumaneedingtobeidentifiedforthatadolescent.Somatic troublesisadichotomousvariableassessedbytriangulatingdata fromtheinterviewsoftheadolescentandbothparents.The crite-riaofinclusionorexclusionwerebasedonthechronicnature ofthetroubles[48],whichweredividedintothreenonexclusive categories:

• earlysomatictroublesininfancy; • geneticdisease;

• chronicsomatictroublesinchildhoodand/oradolescence. Thequalitativeindicatorwasnextadjustedafterco-varying out cases with genetically sourced or early infancy diseases thatpre-andpostnatalmalnutritionandpoor healthcarecould explain. The adjusted indicator was therefore a more likely measureoftheexistenceofchronicsomatictroublesgenerated bymentalshortcomingsduetotheproblemswiththeprimary symbolizationprocess.Finally,anunusualparameterwasalso measured,namelywhetherarelationshipwithapetwas impor-tanttothechild/adolescent.

CBCLDSM-orientedscalesconstructedfromtheCBCL col-lecteddataassessedbyadolescentsandparentswerealsotaken intoaccountinthesearchforpossiblecorrelations.Thescales consideredweretheSomaticProblemsScaleandConduct Prob-lemsScale[49].

Theindependentvariablestakenintoconsiderationwerethe group [adoption, control],the ageat adoption infour ranges

Table6

Comparisonbetweenadoptionandcontrolgroup(p<0.05).

Categories n(%) p

Adoptiongroupn=25 Controlgroupn=25

Signsofprimarytrauma(atleasttwooffollowingcriteriafilled:

rage,control,compliance,withdrawal,stateofagonywhensick

19(76%) 12(48%) 0.04

Somatictroubles 17(68%) 11(44%) 0.04

Chronic 13(52%) 6(24%)

Early 8(35%) 6(24%)

Genetic 3(12%) 2(8%)

Somatictroubles(adjusted) 9(36%) 2(8%) 0.02

Attachmenttopet 9(36%) 2(8%) 0.019

CBCLDSM-orientedSomaticProblemsScales Averagescore(SD)

Parents 0.78 0.25 0.036

Adolescents 2.7 1.0 0.034

[0–5months,6–11months,12–24months,over24months]and theageattimeofinterviewinthreeranges[10–12y,13–14y, 15–16y).The fourrangesof ageatadoptionwere definedin the light of the sensitive periodsidentified inearly cognitive andaffectivedevelopment[25]andcorrelatetotheagegroups definedintheoriginaldevelopmentalresearch[44].Empirical researchidentifiedacut-offageof6monthsatadoptionforno neurologicaldelaycomparedwithnon-adoptees,andthesecond agerangeof6–11monthswasparticularlydesignedtoobserve thedegreeofinternalizingofthealphafunction.Afifthgroup wasinitiallyaddedthattookintoconsiderationtheexperienceof childrenadoptedduringtheirfirstthreemonthsoflife.Although thiscategorizationprovidedinterestingresults,itwasbiasedas addingagroupresultedinlesssignificantsamplesintheother group.Thethreerangesfinallydefined toassesstheeffectof ageatinterviewconsidertheinputofneurobiologicalresearch regardingthe impactof pubertyon affective functions devel-opmentinthebrain,withtwoextremeagegroupsandagroup centeredonthecritical14–15yearsperiod.SeeTable2forthe numberofparticipantsineachofthesecategories.

3.2.2. Mainadoptioneffects

Table6showsthat althoughsignsof primarytrauma were alsopresentamongpeerswithinthecontrolgroup,theywere significantly morefrequently observedin the adoption group (76% vs. 48%;χ2=4.16; p=0.0401). Somatic troubles were alsosignificantlymorefrequentintheadoptiongroup(68%for adopteesvs.44%fornon-adopted;χ2=4.161,p=0.04and36% vs. 8%;χ2=5.712,p=0.02 after adjustment). They included chronicdigestivedisordersinducedbystress(diarrhea,stomach ache),chronic sleepproblemswithanxietyatthe momentof

1 Zerocells(0.0%)haveexpectedcountlessthan5.Theminimumexpected

countis9.5.

2 Zerocells(0.0%)haveexpectedcountlessthan5.Theminimumexpected

countis5.5.

goingtosleeporatnight,andrecurrentepisodesofbronchitis, pneumonia,allergies,eczemaandasthma.

3.2.3. CorrelationbetweenSomaticProblemsScaleand somatictrouble(adjusted)

TheCBCLDSM-orientedSomaticProblemsScalemeasured withparentsandwithadolescents,quantitativelyscored,could add aseverity indicationto the somatic troubles observedin the twogroups.ResultsaresummarizedinTable6.Both par-ents’andadolescents’assessmentscoresshowedonaveragea significant adoption effect (F=4.68; p=0.036and F=4.808;

p=0.034 respectively), valuesbeing on thepathological side when assessedin adoptees.Moreover, somatic problemsand somatictroublecorrelatemoderatelyoverall(r=0.52;p=0.000 forparentsandr=0.31;p=0.038foradolescents),whichmakes sense sincemostqualitativeinformationregardingthe adoles-cents’somatictroubleswasprovidedbyanalysisoftheparents’ transcripts.

3.2.4. Correlationbetweensomaticproblemsand antisocialpersonalitydisorder

Theassociationbetweenantisocialpersonalitydisorderand somatization disorder isa co-morbidity consistently reported in the psychopathology literature, confirming the idea of a shared etiological origin [34].It is also an idea already sug-gestedinthereviewofthepsychoanalyticalliterature,associated withapoorlyinternalizedand/orstabilizedalphafunctionand the construction of the contact barrier. Lilienfeld and Hess [34] foundthatonlysecondarypsychopathology–the antiso-cial lifestyle component of psychopathy ratherthan the core affective traits– correlates with somatization disorder. Other DSM-OrientedScalesconstructedfromtheCBCLcollecteddata were alsoanalyzedusingANOVAI.Theonlyotheradoption effect observed was that adoptive parents rate conduct prob-lemshigherthanbiologicalparentsdo(F=5.9;p=0.019)and higher thantheir childrendo.Actually, the somaticproblems score assessedbyparents correlates overall withthe conduct problemsassessedbythem(r=0.55;p=0.000),acorrelation

that remains significant after agesand gendervariables have beencontrolledfor.

3.2.5. Petattachment

As indicated in Table 6, adopted children are indeed morelikely to attach importance to a relationshipwith their pet (2=5.71, p=0.0193), especially in childhood and pre-adolescence.

In summary, the quantitative analysis suggests the greater presence of observable signs of primary trauma andchronic somatic troubles in the adoption population compared tothe controlgroup.Thedifferenceinaveragebetweenadoptionand controlgroupsisreflectedbytheDSM-OrientedScalescored byparentsandadolescentsforthesomatictroubles. Addition-ally,theSomaticProblemsScalescoresprovidedbytheparents correlateoverallwiththeConductProblemScalescores,afact whichisinaccordancewiththecorrelationoftenobservedin theliterature[34]betweensomatizationandantisociallifestyle. Sadly,adopteesalsoseemedmorelikelytoconsidersuicidethan non-adoptees.

4. Discussion

4.1. Somatizing

Although not necessarily the variable conveying the most powerfuladoptioneffect, onestrikingfindinginthe thematic analysiswas the highprevalence of chronicsomatic troubles amongadoptees(Table4)furtherconfirmedbythecomparison ofCBCLDSMSomaticProblemsOrientedScaleswithin adop-tionandcontrolgroups(Table6).Whatisstrikingabout this isthatinthebestcase,itsignalsahigh-costsolutionagainsta disorganizationthreat(e.g.throughthetransitionaltime/spaceit providesforthesymbolizationofadisruptiveevent)[50],while intheworstcaseitsignalsthe(renewed)experienceofa(past) stateofagony(e.g.theadolescentfeelinglikedyingwhensick –acharacteristicfeatureofthestudy)oncealldefensesagainst thereturnofthesplitoffhavebeenoverwhelmed/abandoned. Althoughthesomaticproblemsscoresofbothparentsandthe adolescentcorrelate(moderately)withthepresenceofsomatic troubles identified in the interviews (r=0.52; p=0.000 and

r=0.31; p=0.038 respectively), parents seemed to underrate suchtroubles.Themeansomaticproblemsscoreofadolescents seemedconsistent withthe higher perceived somatic distress amongtheadoptees andmightillustrate the psychoanalytical concept of state of agony correlated toprimary trauma. Pos-sibleexplanationsfromapsychoanalyticalperspectiveofwhy theparentsunderratedsomatic troublescompared tothe ado-lescents–andcomparedtotheresultsofthethematicanalysis– couldbe(1)thepresenceofasocialdesirabilitybiassupported byasecondarythoughtprocessmorepresentintheadultthan inthe(pre)adolescent,(2)anunderlyingdenialofthesuffering enduredbytheadolescent,becauseiteitherdamagestheparents’

3 Zerocells(0.0%)haveexpectedcountlessthan5.Theminimumexpected

countis5.50.

illusionofbeingall-powerful[51]orthreatensareaswhichare traumaticfortheparentsthemselves,or (3)both.The theoret-icallinkestablishedbytheliteraturereviewmakesittempting tocorrelatesomatizingtoalowerdegreeofalphafunctioning andofprimary symbolization[52],whichcouldbeestimated by theratio betweensignsof alpha functioning(e.g.creative gamesandactivities,successinachievingowngoals,capacity tobealone,driveforacquiringknowledge,capacitytomanage time,etc.)andalphadysfunctiononalargersample.

4.2. Degreeofalphafunctioning

Threeaspectsofthefailingfunctionwhichemergedduring thestage-by-stagethematicanalysiswereapreoccupationwith thepresence/absenceofotherfamilymembers,temporalityand weaktransitionalbarrier.Oneadopteevividlycomplainedthat herparentsdidnotleaveherenough(internal)objectstooccupy theirabsence,suggestingthatthehallucinatorythinkingbythat adolescentwasdeprivedofthenecessaryinternalobjects. Inter-nalizing (of the alpha function) seemed tobe aprocess that adoptees hadparticularlydifficulties with(atleast morethan non-adopteesseemedtohaveonaverage).Meanwhile,the attri-butionofexaggeratedimportance topets(Table6)seemedto play ahugecalming role andtherefore tofavorinternalizing of the alpha function,especiallyamongthe youngest adoles-cents.Insuchcircumstances,thepetmayprovidethefunction ofprotectiveshield,butalsothatofobjectpresenting(rejecting, retrieving).Althoughthisisaratherdemandingtaskforapet, itmaybetheonlyonewiththeabilitytoperformit,andthis makesitprecious.

4.3. Narcissisticidentitypathologies

Onewaytomapthecategoriesofanxietyanddefense mech-anisms which emerged from the thematic analysis (Table 4) andpresenceofnarcissisticidentitytroublesamongadolescents (Table1)wastoclassifycategoriesasafunctionofthe increas-ingleveloforganizationofthedefense,andthenateachlevel to:

• identify the possible shadow of the main primary defense mechanism(theprimarysplitting)[26];

• detectanypresenceofthethreemainandadditionaldefense mechanisms whichwere once put inplaceby the childto counter the return of the split off primary trauma as well as detectthepresence ofothersolutionsforbindingexcess energyandreducingexcitationlevels(Table5).

The categories of anxieties and defensemechanisms (e.g. helplessnessandwithdrawal)canassumeadifferenttheoretical meaningaccordingtotheorganizationofthedefensive mech-anism(e.g.avoidingotherswhensadasanamputationofpart oftheself,orFalseSelfindicatedbywithdrawalintoownlittle world).

Themappingoftheresultsshowsthatallthemainsignsofthe presenceofnarcissisticidentitytroublesarepresentTherefore itappearsfromthecategoriesthatemergedfromthedata-driven

andtheirtheory-drivenmappingwiththecomponentsofa psy-choanalyticalmodelassumingatraumaticoriginfornarcissistic identity troubles in adolescents that adoptees of the studied groupshowedahigherprevalenceofnarcissisticdefensesthan their non-adoptedpeersdid (76%of adoptees vs.48%inthe controlgroup).

4.4. Sensitiveperiods

Implicitsensitivedevelopmentalperiodssupportedby vari-oustheoreticalperspectiveswoulddeserveacloserlookinfuture studiesonlargeradoptionpopulationsamples,inparticular: • the second six months of life and the following months

regardingthelevelofinternalizingofthealphafunctionand itslong-lastingeffectsonsomaticrisk;

• the ageof 5–8y for the perceptionof differentiationanda firstroundofthequestfororiginsamongadoptees(e.g.the childrealizesthathe/shehasbeenadoptedatthetransition fromnurserytoprimaryschool[53],leadingtomomentsof profoundsadnessandmalaise,butalsospecifichealth prob-lems);

• theageof14–15ywithitsemotionalreactivitypeak[39]. Especially,possibleeffectsofparentalmentaldimensionson thewayinwhichtheinfantandlatertheadolescentnegotiates thesethreesensitiveperiodsmightbeworthmeasuring.Inthe smallstudiedsample(n=25),the9adolescentsadoptedduring theirsecond sixmonthsof life(5–11monthsoldatadoption) alsoshowed overallthehighest frequencyof chronicsomatic troublesatadolescence(80%consideringtheadjusted indica-torcomparedtoanaverageoverallof 36% forthe adoptees). Thissubgroupwasthereforeamaincontributortothepresence ofsomaticcomplaintsamongthegroupofadoptees.Thismay meanthatsignsofprimarytraumaandsomatictroublesarenot necessarilycongruent,althoughtheybothsignalanissuewith primarysymbolization.Thecurrentstudysuggeststhat interna-tionaladoptionisverylikelycorrelatedtoprimarytrauma(even adolescentsadopted intheir first trimesterof life showedthe signsinthisstudytothesameextentastheirpeersadoptedata laterstage),toprimarysplittingdefensemechanismsandtolater narcissisticidentitypathologieswithvariouslevelsofdefense organizing.Verylikely,eventhelessdisruptivecircumstances of very earlyadoption canhardly preventadrastic failureof the maternal reverie,so that ayoung adoptee hastosplit off from experienced, representation-less material, drivenby the compulsiontorepeat.Thispointaside,narcissisticdefense orga-nizationpreventingthereturnofthestateofagony,isasolution that preserves the adolescent fromthe disorganization threat, frompsychoticdisordersandtheirassociated defense mecha-nisms,anxietiesandrelationshippatterns.Keepingthesplitoff trauma lockedawayconsumesthe self.Still,it mightbe rea-sonabletoassumethat internalizingandstabilizing thealpha function–the primary symbolizationprocessenabler– inthe presenceofanadequatematernalreverieprovider(e.g.adoptive parent),canoccurinparallel.Aprivilegedperiodforthe (prelim-inary)acquisitionofthisfunctionisthesecondsemesteroflife.

Thisperiodmaybeparticularlysensitiveforadoptees,andfor anychildthathasexperiencedprimarytrauma.Howdifferences betweengroupsymboliccontents(culture/language),whichare oftenafeatureofinternationaladoption,interferewithoraffect the chance for the adopted child tograsp the alpha function fromthematernalreverieathand,isanotherquestionthatmay deserve furtherconsideration.Theextenttowhichanadoptee tendstosomatize(measuredbythe adjustedsomatic troubles indicator)maybeanindicationofthedegreeofsuccessofthe alphafunctionstabilizationinthissensitiveperiod.

4.5. Methodologicallimitations

Thereviewoftheliteratureprovidedtheinitialjustification for reading the clinicalmaterial collectedthrough a develop-mentalparadigm withadifferent,psychoanalytical, paradigm bythefactsthat:

• bothagreeonthekeyfactorsthatshapeearlydevelopment; • the method chosen for material collection based on

semi-structured interviews gave the necessary place to the subjectivityoftheinterviewees.

Theparadoxofusingtheindividualsingularitytoreachintra andintergroupinferencesshouldhowevernotbeoverlooked. This point aside, the subjectivity of the researcher,who was workingwithasingletheoreticalframework,i.e.thegrounded theory approach, has already been mentioned as a potential sourceof bias,althoughadeliberateeffortwasmade to chal-lengethatvisionwiththeresultsprovidedbyothertheoretical perspectives,forexampleneurosciences.Questionscouldalso beraisedaboutinternalvalidityandreliabilitylimitationsdueto usingonlyoneencoder,althoughthesewerepartiallycorrected for. A moreserious methodological limitation maylie inthe factthatbothtermsoftheresearchquestionwere operational-izedwithasingletheoreticalmodel[26],implicitlyvalidating the existenceofthefirstterm fromthe clinicalobservation of the secondmeasured atadolescence.Adopteeswere assumed defactotobemorelikelytohaveexperiencedprimarytrauma, an assumption supported by empirical research whichshows thatpreadoptionlengthoftimeandseverityofcaregiving depri-vation aretwopredictorsof neurologicalandage-levelmotor development delays. From a quantitative perspective, for the measurementofriskofprimarytraumacouldhavebeenbetter approximatedbymeasuringageatadoptionmoderatedbythe countryoforiginwithaconstructedratio.Giventhelimitedset of data,thisoption was discarded.The adoption factoralone remained,anddidinfactprovesufficienttoshowamainoverall effect.

5. Conclusion

Theprimary objectiveofthecurrentstudywastoexamine severityofearlydeprivation–assumedtohavebeenexperienced preadoption–asariskofnarcissisticidentitypathologiesin ado-lescenceinthespecificcontextofinternationaladoption.The answerforthestudiedsampleisclearlythatthereisaneffect,

althoughonlyamoderateone.Theaffectiveandcognitive reor-ganizationstakingplaceduringadolescenceexposeadolescents’ narcissisticvulnerability.Inthiscontext,adopteesshowed: • a higher activation of narcissistic defenses, in particular

compliance,rage, control andwithdrawal, whichcan indi-catetheneedtoresorttosplittingandtheexistenceofasplit offpart;

• ahighersomatization,incomparisonwiththeirnon-adopted peers.

The prevalence of the more silent physiological solution (somatization) vs the behavioral solution may indicate poor internalizationofthealphafunction.Furtherstudiesareneeded inordertounderstandtheinteractioneffects ofthe following factors:ageatadoption,parents’empathyandcapacityto men-talize[54],supportfromothers,siblingconfiguration,difference ingroupsymboliccontentswhichareoftenafeatureof interna-tionaladoption,etc.).

Twomaintheoreticalimplicationsemergefromthisstudy: • existing theoretical models describing the general

popula-tion’saffectiveandcognitivedevelopmentanddysfunctions areprobablysufficienttocoverandunderstandthepopulation ofadolescentsadoptedininfancy;

• themodelproposedbyRoussillonwasparticularlyusefulin correlatingrecurrentdefenseorganizationswithformsof nar-cissisticidentitypathologiesandthehigherriskofsuicidethis populationincurs.

To the question:“Are adoptees a populationwith specific issuesrequiringspecifictheoreticalwork?”theansweris there-foreno.However,thisresearchsuggeststhat,inadditiontotheir higherriskofsuicide,specialattentionneedstobepaidtothe higherlevelofsomaticcomplaints.Thehighersomaticriskthat oscillateswithinthe studiedpopulationbetweenself-defense, self-treatment andthe experience of astate of agony, proba-blysignalstherecurrent failureofthe primary symbolization processes,bothsecondaryandprimary,suggestingtwopossible areasofwork.Oneispreventive,theotheristherapeutic.The therapeuticperspectivesuggeststhatalltherapiesfocusingon therepairorcompletionofaproblematicprimarysymbolization processarewellworthexploringandusingwiththese adoles-cents. With respect toprevention, stressshould be placedon waystodecreasethesomaticriskand,asacorollary,tofavorthe internalizingbythechildofthealphafunction.Inthisrespect, althoughadoptionasearlyaspossiblemayappeartobethebest optioninordertominimizethelong-lastingeffectsofcaregiving deprivationobservedhere,largerstudiesmeasuringtheeffectof sensitiveperiodsinlatesomatic risk(andinternalizingof the alphafunction)couldcontradictsuchahastyconclusion.

Disclosureofinterest

Theauthors declare that theyhaveno conflictsof interest concerningthisarticle.

References

[1]BrussetB.L’avant-couptrouvé/créé.RevFrPsychanal2009:1539–43. [2]GreenA.Lescaslimite.Delafolieprivéeauxpulsionsdedestructionet

demort.RevFrPsychanal2011:375–90.

[3]JeammetP.Ledéveloppementdel’individu:uneco-construction perma-nenteàlamercidesrencontres.RFAS2013:11–4.

[4]KernbergOF. Quelquesobservationssurleprocessusde deuil.Année PsychanalIntern2011:153–75.

[5]WidlöcherD.Stupeuretfiguresdansladépression.In:Dépressiondubébé, dépressiondel’adolescent.Eres:Toulouse;2010.p.13–27.

[6]KimWJ.Benefitsandrisksofintercountryadoption.Lancet2002:423–4. [7]BrandAE,BrinichPM.BahaviorProblemsandMentalHealthProblems inAdopted,FosterandNon-adoptedChildren.JChildPyscholPsychiatry 1999:1221–9.

[8]Gagnon-OosterwaaN,etal.Pre-adoptionadversity,maternalstress,and behaviorproblemsatschool-ageininternationaladoptees.JApplDev Psychol2012:236–42.

[9]PalaciosJ,MorenoC,RománM.Socialcompetenceininternationally adoptedandinstitutionalizedchildren.EarlyChildResQ2013:357–65. [10]RoeberBJ,et al.Grossmotordevelopment in childrenadopted from

orphanagesettings.DevMedChildNeurol2012:527–31.

[11]Wiik KL, et al. Behavioral and emotional symptoms of post-institutionalizedchildreninmiddlechildhood.JChildPsycholPsychiatry 2011:56–63.

[12]HjernA,LindbladF,BoV.Suicide,psychiatricillness,andsocial mal-adjustment inintercountryadopteesinSweden:acohortstudy.Lancet 2002:443–7.

[13]LaubjergM,PeterssonB.Juveniledelinquencyandpsychiatriccontact amongadopteescomparedto non-adopteesinDenmark:Anationwide register-basedcomparativestudy.NordJPsychiatry2011:365–72. [14]DrieuD,JohnstonG.Résonancestraumatiquesfamilialeschezdes

adoles-centsadoptésvenantd’uneautreculture.Dialogue2007:45–56. [15]CohenNJ,etal.ChildrenadoptedfromChina:aprospectivestudyoftheir

growthanddevelopment.JChildPsycholPsychiatry2008:458–68. [16]RoskamI,etal.AnotherwayofthinkingaboutADHD:thepredictiverole

ofearlyattachment.SocPsychPsychEpid2013:133–44.

[17]Rutter M,etal.Earlyadolescent outcomesof institutionallydeprived andnon-deprivedadoptees.III.Quasi-autism.JChildPsycholPsychiatry 2007:1200–7.

[18]SmykeAT.Developmentandinstitutionalcare.DevMedChildNeurol 2012:487.

[19]JulianMM.AgeatAdoptionfromInstitutionalCareasaWindowinto theLastingEffectsofEarlyExperiences.ClinChildFamPsycholRev 2013:101–45.

[20]Guedeney N,Dubucq-GreenC.Adoption,lesapportsde lathéoriede l’attachement.Enfances&Psy2005:4–94.

[21]Anzieu-PremmereurC.Lejeudanslesthérapiesparents-bébés.RevFr Psychanal2004:143–55.

[22]DuparcF.Winnicottetlacréationhumaine.In:Winnicottetlacréation humaine.Toulouse:Eres;2012.p.219–39.

[23]GrinbergL,SorD,TabakdeBianchediE.Nouvelleintroductionàlapensée deBion.Lyon:CesuraLyon;2006.

[24]KleinM.Lesstadesprécocesduconflitœdipien.In:Éssaisdepsychanalyse, 1921–1945.Paris:Payot;1928.p.229.

[25]CicconeA.Psychopathologiedubébé,del’enfantetdel’adolescent.In: Manueldepsychologieetdepsychopathologiecliniquegénérale.Masson; 2007.

[26]RoussillonR.Primitiveagonyandsymbolization.London:KarnacBooks; 2010.

[27]RoussillonR.Agonie,clivageetsymbolisation.Paris:Presses Universi-tairesdeFrance;1999.

[28]FaganM.Relationaltraumaanditsimpactonlate-adoptedchildren.JChild Psychother2011:129–46.

[29]HarfA,etal.L’enfantadoptéàl’étranger,entrelanguematernelleetlangue d’adoption.Lapsychiatriedel’enfant2012:315–38.

[30]FieldT,DiegoM,Hernandez-ReifM.Prenataldepressioneffectsonthe fetusandnewborn:areview.InfantBehavDev2006:445–55.

[31]FonagyP,GergelyG,TargetM.Theparent–infantdyadandtheconstruction ofthesubjectiveself.JChildPsycholPsychiatry2007:288–328. [32]MascaroR,etal.Evaluationdeseffetsduplacementprécocedubébéen

pouponnière.Devenir2012:69–115.

[33]SchoreAN.Theeffectsofearlyrelationaltraumaonrightbrain develop-ment,affectregulationandinfantmentalhealth.InfantMentalHealthJ 2001:201–69.

[34]LilienfeldSO, HessTH.Psychopathicpersonalitytraitsand somatiza-tion:sexdifferencesandthemediatingroleofnegativeemotionality.J PsychopatholBehavAssess2001.

[35]Dayan J, Guillery-Girard B. Conduites adolescentes et développe-mentcérébral:psychanalyseetneurosciences.RevAdolesc2011:479– 515.

[36]McRaeK,etal.Thedevelopmentofemotionregulation:anfMRIstudyof cognitivereappraisalinchildren,adolescentsandyoungadults.SocCogn AffectNeurosci2012:11–22.

[37]StortelderF,Ploegmakers-BurgM.Adolescenceandthereorganizationof infantdevelopment:aneuro-psychoanalyticmodel.JAmAcadPsychoanal DynPsychiatry2011:203–532.

[38]LamotteF,etal.Lesachoppements delaconstructionidentitaire dans les adoptions internationales. Neuropsychiatr Enfance Adolesc 2007: 381–8.

[39]PfeiferJH,BlakemoreSJ.Adolescentsocialcognitiveandaffective neu-roscience: past, present,and future.Soc Cogn AffectNeurosci 2012: 1–10.

[40]StraussA,CorbinJM.Basicsofqualitativeresearch:groundedtheory pro-ceduresandtechniques.ThousandOaks,CA,US:SagePublications;1990 [Inc.270].

[41]AberJL,etal.Theparentdevelopmentinterview.1985.

[42]SteeleM.Alongitudinalstudyofpreviouslymaltreatedchildren: attach-mentrepresentations,adoption,indevelopmentalscience,psychoanalysis: integration,innovation,Y.C.,s.,Center,Editor.2003:NewHaven,CT.

[43]AchenbachTM,RescorlaLA.ManualfortheASEBAschool-ageforms andprofiles.Burlington:UniversityofVermont,researchcenterfor chil-dren,youth,andfamilies;2001.

[44]Halfon O. Adopted adolescents: attachment and behavior problems. “Core project” submitted to the teams of the network “adop-tion/attachment/adolescence”.Lausane:LausanneUniversityChildand AdolescentPsychiatryDept;2009.

[45]StievenartM,etal.Friendsandfamilyinterview:measurementinvariance acrossBelgiumandRomania.EurJDevPsychol2012:737–43. [46]VoynnetFourboulC.Ceque«analysededonnéesqualitatives»veutdire.

Revueinternationaledepsychosociologieetdegestiondescomportements 2012:71–88.

[47]KohutH.Observationsonthepsychologicalfunctionsofmusic.JAm PsychoanalAssoc1957:389–407.

[48]KreislerL.Lapsychosomatiquedel’enfant.4eÉd.Paris:Presses

Univer-sitairesdeFrance,coll.“Quesais-je”;1992.

[49]AchenbachTM,DumenciL,RescorlaLA.DSM-orientedandempirically basedapproachestoconstructingscalesfromthesameitempools.JClin ChildAdolescPsychol2003:328–40.

[50]DebrayR.Expression somatiqueettransitionnalité.Rev FrPsychanal 1995:1571–3.

[51]ColbèreMT.Adoptionetadolescence:parentsenquestion(s).Dialogue 2001:89–98.

[52]FineA.Interrogationssurledéfautdesymbolisationprimairecomme paramètreduphénomènepsychosomatique.In:Métapsychologie:écoute et transitionnalité. Paris: Presses universitaires de France; 1995. p. 1699–704.

[53]BebirogluN,PinderhughesEE.Mothersraisingdaughters:new complex-itiesinculturalsocializationforchildrenadoptedfromChina.Adoption Quarterly2012:116–39.

[54]DebrayR,BelotRA.Lapsychosomatiquedubébé.Paris:Presses Univer-sitairesdeFrance;2008.