Essays on uncertainty and foreign direct investments

Thèse

Mankan Mohammed Koné

Doctorat en agroéconomie

Philosophiæ doctor (Ph. D.)

Essays on Uncertainty and Foreign Direct

Investments

Thèse

Mankan Mohammed Koné

Sous la direction de:

Lota D. Tamini, directeur de recherche Carl Gaigné, codirecteur de recherche

Résumé

L’objectif de cette thèse est d’explorer l’impact de l’incertitude sur les IDE. Elle s’intéresse plus particulièrement à l’industrie agroalimentaire en tenant compte des spécificités de la chaîne de valeur agricole. Les flux et les stocks d’IDE sont généralement très instables et il est admis que l’incertitude est le principal facteur causant les baisses fréquentes de l’IDE au niveau mondial. Nous voulons savoir si et dans quelle mesure l’incertitude causée par la volatilité de la demande et de l’offre peut affecter les IDE dans l’industrie agroalimentaire. À cette fin, nous utilisons des modèles théoriques et empiriques.

Dans le premier chapitre, nous étudions empiriquement la mesure dans laquelle l’incertitude provenant des variabilités de la demande du marché, de la production et du commerce peut expliquer la probabilité d’avoir des IDE dans l’industrie agroalimentaire. On s’attend à ce que les IDE soient retardés lorsque l’incertitude augmente car les entreprises qui font ces investis-sements mobilisent des ressources conséquentes pour réaliser leurs IDE. Nous utilisons un modèle d’analyse de survie et des données d’IDE bilateraux. Cela nous permet de constater que la volatilité réduit la probabilité d’observer l’IDE entre les pays. Ce comportement est observé dans l’industrie agroalimentaire mais aussi dans d’autres industries. Cependant, toutes les sources de variabilité ne jouent pas nécessairement un rôle. Par exemple, les IDE des entreprises multinationales européennes et américaines dans l’industrie alimentaire sont négativement affectés par la volatilité des importations du pays de destination. Les IDE de ces pays dans l’industrie des produits chimiques sont négativement affectés par la volatilité de la production. La volatilité des exportations diminue l’attrait de capitaux étrangers dans le secteur des équipements de transport des pays d’accueil.

Dans le second chapitre, nous construisons un modèle théorique pour expliquer le compromis entre les exportations et les IDE compte tenu de l’incertitude quant à la taille de la demande. Nous observons que l’incertitude de la demande induit un comportement d’attente des entre-prises multinationales qui explique pourquoi les IDE peuvent être retardés dans les marchés où l’incertitude est grande. L’IDE devient une option réelle dans laquelle l’attente permet de réduire l’incertitude. Nous adoptons la littérature sur l’analyse des options réelles pour construire notre cadre théorique. En plus de l’incertitude de la demande, nous examinons également des facteurs comme les coûts au commerce et l’environnement de la concurrence.

Nous observons qu’une forte concurrence, une faible différenciation des produits et une dimi-nution des barrières commerciales amplifient le comportement d’attente des multinationales. Par exemple, la réduction des coûts au commerce peut nuire aux IDE, car elle augmente leur sensibilité à l’incertitude et l’attente devient une option plus intéressante.

Dans le dernier chapitre, nous analysons les IDE dans l’industrie agroalimentaire en tenant compte des différences de volatilité dans l’offre agricole entre les pays. Cette analyse nous permet d’étudier la question de l’incertitude dans l’industrie agroalimentaire du point de vue de la chaîne d’approvisionnement, car nous considérons l’incertitude dans le secteur en amont. En fait, les variations des prix agricoles ou des quantités livrées aux transformateurs par les agriculteurs sont souvent importantes et imprévisibles. Par conséquent, ces transformateurs de l’industrie agroalimentaire sont exposées à une incertitude croissante et persistante. Notre cadre théorique tient compte du pouvoir de marché des entreprises de transformation et des IDE de type horizontaux et verticaux. Nous obtenons que même les entreprises neutres au risque sont préoccupées par la variabilité de l’offre. En effet, dans le contexte de l’industrie alimentaire, la relation entre le profit et le choc d’offre est concave étant donné la concurrence imparfaite et le moment de la résolution de l’incertitude. Notre approche empirique confirme que les entreprises multinationales réalisent leurs décisions en matière d’IDE en considérant les disparités de variabilité de l’offre entre les pays parce que la volatilité du secteur agricole dissuade les IDE. Nous testons cette prédiction à l’aide de données bilatérales de stocks d’IDE dans l’industrie agroalimentaire.

Abstract

The three essays of this thesis explore the impact of uncertainty on FDI in the food industry by taking into account the specificities of the food value chain. FDI flows and stocks are very unstable and evidence suggests that uncertainty is the main factor causing frequent declines in FDI globally. We want to know whether and to what extent the uncertainty caused by the volatility of demand and supply affects FDI in the food processing industry by using theoretical and empirical models.

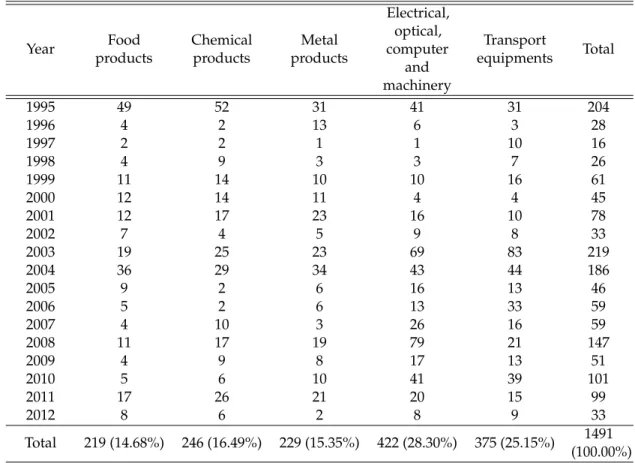

The first essay empirically studies whether uncertainty related to variables such as volatile market demand, production variability and trade volatility affects the hazard rate of FDI in the food industry. As FDI is irreversible investment, it is likely to be delayed when uncertainty increases. Using a survival analysis model and bilateral FDI data, we find that volatility reduces the hazard rate of FDI. This behavior is observed in the food industry but also in other industries. However, not all sources of variability are relevant. For example, FDI by European and US multinational companies in the food industry is negatively affected by the import volatility of the country of destination. FDI of these countries in the chemical industry is negatively affected by the volatility of production. Export volatility plays a role in attracting foreign capitals in the transport equipment sector of host countries.

The second essay provides a theoretical model to explain the choice between export and FDI given the uncertainty about the size of demand. The fact that FDI is delayed when uncertainty increases is explained by the wait-and-see behavior of multinational companies when investing in very uncertain foreign markets. FDI decisions can be considered as real options in which the decision to invest can be postponed to reduce uncertainty. We build a model that relies on the literature of real options. In addition to the uncertainty of demand, we also examine factors such as trade costs and the competitive environment. We find that intense competition, low product differentiation and reduction of trade barriers amplify the wait-and-see behavior of multinational firms. For example, trade liberalization can be harmful for FDI, as it increases the sensitivity of FDI to uncertainty and waiting becomes a more valuable option.

In the last essay, we analyze FDI in the food processing industry, given the differences in the volatility of agricultural supply between countries. This analysis allow us to examine the issue of uncertainty in the food processing industry from a supply chain perspective, as we consider

uncertainty in the upstream sector. In fact, variations of farm prices or of quantity delivered to processors by farmers are problematic as they are large and unpredictable. Consequently, food processing firms, as they use massively primary agricultural commodities as ingredients, are exposed to an increasing and persistent uncertainty. Our theoretical framework takes into account the market power of processors and horizontal and vertical FDI are discussed. We find that even risk-neutral companies are concerned by the variance of supply. Indeed, in the context of the food industry, the relationship between profit and supply shock is concave given imperfect competition and the timing of the resolution of uncertainty. Our empirical approach (a gravity model) confirms that multinational firms achieve their FDI decisions by considering the difference of supply shocks between countries as the volatility of the agricultural sector deters FDI. We test this prediction using bilateral FDI stocks data in the food processing industry.

Contents

Résumé iii Abstract v Contents vii List of Tables ix List of Figures xi Acknowledgements xiv Foreword xv Introduction 11 Empirical Analysis of the Timing of FDI under Risk at the Industry Level 18

1.1 Introduction . . . 19

1.2 An overview of the FDI data. . . 23

1.3 Empirical framework . . . 25

1.4 Estimation results . . . 31

1.5 Robustness check . . . 38

1.6 Conclusion . . . 43

1.7 Bibliography . . . 43

2 FDI, Trade Barriers and Imperfect Competition under Uncertainty: A Real Option Approach 48 2.1 Introduction . . . 49

2.2 Theoretical Model . . . 52

2.3 Structure of the game . . . 58

2.4 Resolution and Equilibrium . . . 59

2.5 Role of product differentiation . . . 63

2.6 Conclusion . . . 67

2.7 Bibliography . . . 68

3 Does Agricultural Market Uncertainty Reduce FDI in the Food Processing Industry? 72 3.1 Introduction . . . 73

3.3 Model of foreign production decision in uncertainty . . . 77 3.4 Empirical evidence . . . 87 3.5 Conclusion . . . 97 3.6 Bibliography . . . 99 Conclusion 104 A Appendix of chapter 1 107 A.1 Lists of countries and industries. . . 107

A.2 Description of variables . . . 108

B Appendix of chapter 3 109 B.1 The timing of the resolution of uncertainty . . . 109

B.2 FDI model with competitive fringe . . . 110

B.3 Multiplicative shock with no competitive fringe . . . 117

B.4 Diversification: additive shock . . . 121

B.5 List of countries . . . 122

B.6 Volatility measure . . . 123

B.7 Additional regressions . . . 123

B.8 Correlation between monthly and annual volatility 2010-2014 . . . 127

List of Tables

1.1 New FDI relationships by industry and year . . . 24

1.2 Descriptive statistics of the volatility measures . . . 29

1.3 Cross-correlation of the volatility measures . . . 30

1.4 Regression table, dependent variable: hazard rate, probability of FDI in the food industry . . . 35

1.5 Regression table, dependent variable: hazard rate, probability of FDI in the chemical industry . . . 36

1.6 Regression table, dependent variable: hazard rate, probability of FDI in the transport equipment industry . . . 37

1.7 Regression table, dependent variable: hazard rate, probability of FDI in the food industry . . . 39

1.8 Regression table, dependent variable: hazard rate, probability of FDI in the chemical industry . . . 40

1.9 Regression table, dependent variable: hazard rate, probability of FDI in the transport equipment industry . . . 41

1.10 Regression table, dependent variable: hazard rate, probability of FDI in all industries. . . 42

2.1 Baseline parameter values . . . 64

2.2 Simulation of the optimal threshold with different volatility values . . . 64

2.3 Simulation of the optimal threshold with different trade costs levels . . . 64

3.1 Descriptive statistics of the standard deviation of agricultural price indices, 1997-2012 . . . 93

3.2 Regression table, dependent variable: FDI stocks, PPML . . . 94

3.3 Regression table, dependent variable: FDI stocks, several specifications . . . . 98

A.1 List of countries . . . 107

A.2 List of industries . . . 108

A.3 Variables definition and sources . . . 108

B.1 List of countries . . . 122

B.2 Regression table, dependent variable: FDI stocks, PPML, regression using HP filter . . . 124

B.3 Regression table, dependent variable: FDI stocks, PPML, regression excluding United States . . . 125

B.4 Regression table, dependent variable: FDI stocks, several specifications, regres-sion excluding United States . . . 126

B.5 Correlation between monthly and annual volatility 2010-2014 . . . 127 B.6 Variables definition and sources . . . 128 B.7 Summary statistics of main variables . . . 128

List of Figures

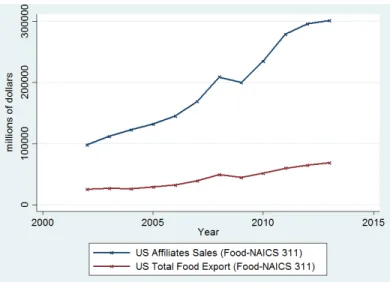

0.1 Evolution of trade and foreign affiliate sales of US food processing . . . 1

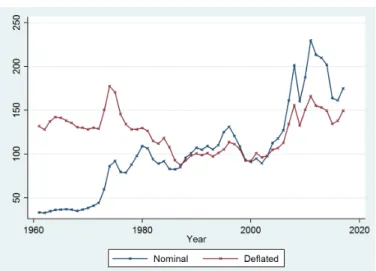

0.2 Annual FAO Food price index 1961-2017, reference year: 2002-2004 . . . 5

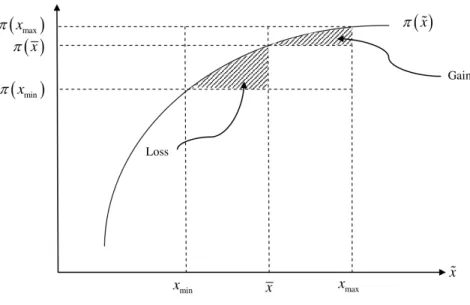

0.3 Risk with a convex profit function . . . 6

0.4 Risk with a linear profit function . . . 6

0.5 Risk with a concave profit function . . . 7

1.1 Survival function with respect to number of years: All industries (left), by industry (right) . . . 26

2.1 Optimal entry thresholds with respect to the degree of product substitution for different values of uncertainty (left) and relative risk aversion (right) . . . 65

2.2 Optimal entry thresholds with respect to preferences for local products for different values of uncertainty (left) and relative risk aversion (right) . . . 66

3.1 Outward FDI stock evolution for Europe (left) and United States (right), 1997-2012 90 3.2 Average bilateral FDI stock by destination (US millions dollars), main hosts: Europe (left), United States (right), 1997-2012 . . . 90

3.3 Average bilateral FDI stock by origin (constant 2010 US millions dollars), main European investors, 1997-2012 . . . 91

3.4 Relation between estimated distance elasticity and destination country agricul-tural uncertainty. . . 96

A major motive for entering any country is the pursuit of profit.

Mark Casson & Teresa da Silva Lopes

Acknowledgements

I first thank the Lord, ALLAH, creator of the universe, for all his blessings in my life, for giving me strength and patience during these five years.

I address a special thanks to my supervisor, Professor Lota D. Tamini, professor at the Faculty of Agricultural Economics and Consumer Sciences, on whom I was able to count to guide me in this research work by his advice and encouragements. To my co-supervisor, Professor Carl Gaigné, I am grateful for all your consideration, your help and your assistance during the realization of my thesis. I would also like to thank Professor Bruno Larue who taught me in the international trade class and accepted to be a member of my thesis committee. Thank you Professor José de Souza and Professor Sylvain Dessy Eloi for accepting to be a member of my thesis committee.

I also thank the administration and the Faculty of Agricultural Economics and Consumer Sciences at Laval University for the academic and social training I received during these studies. I thank the Centre de Recherche en économie de l’Environnement, de l’Agroalimentaire, des Transports et de l’Énergie (CREATE) and the Centre d’études pluridisciplinaires en commerce et investissement internationaux (CEPCI) for all the support available to students.

To my father and my mother, Mr. Ibrahima Koné and Mrs. Koné born Cissé Fanta, may you know all the consideration and love I have for you, and may GOD reward you. To my brothers and sisters (Kadi, Zarha, Noura, Faman, Soumahiya), to the big family for their prayers and their support of which I am always the object. To my friends and acquaintances who by simple gestures showed me the way to follow and encouraged me during all these years. Special thanks to Jean-Baptiste, Wilfried, Safiatou and Charli, Lacina, Rocard, Ismaelh and Fatim, Bouba Housseini, Ismael Mourifie. Thank you for your support.

Foreword

This paper represents a work to understand the effect of uncertainty on FDI in the food industry. It was written as part of a thesis by article. Each chapter explores a different topic of the relationship between uncertainty and FDI decisions and, therefore, corresponds to a separate article. All articles are preceded by a general introduction and the document ends with a general conclusion.

All articles have been written by the author of this thesis with his research directors, Pr Lota D. Tamini and Pr Carl Gaigné. This is an opportunity to thank them for their support and contribution to this work. The author of this document, however, remains the first author of each of the three articles.

Introduction

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in the food processing industry has become important world-wide. In the food processing industry, greenfield FDI projects reached US $ 22 billion in 2014 and 2015 and cross-border mergers and acquisitions purchases reached US $ 28 billion in 2015, in comparison to US $ 34 billion in 2014 (UNCTAD,2016). Moreover, multinational firms’ total trade of processed food has been growing but to a lesser extent than foreign affiliates sales by US agri-food multinational firms (Figure0.1for the USA).1This evolution has been facilitated by the fact that markets are more economically and financially open. Furthermore, foreign markets represent a source of growth opportunities for multinational firms, which is materialized by the preponderance of large multinational firms abroad. FDI also enables firms to circumvent the barriers to trade. Previous empirical models found that the drivers of FDI in the food industry are entry barriers, market size, per-capita income, export price, and protection measures of host country (Adelaja et al.,1999;Gopinath et al.,1999;Makki et al., 2004;Hajderllari et al.,2012;Phillips and Ahmadi-Esfahani,2012).

Figure 0.1: Evolution of trade and foreign affiliate sales of US food processing

FDI flows constitute an international movement of capital (tangible or intangible) to establish

a subsidiary or affiliate abroad or to establish joint ventures or merge with a foreign com-pany (Buckley,1998). Moreover, FDI implies that the investing firm acquires a substantial controlling interest in a foreign firm (at least 10% of the control). There are many purposes of FDI in the food processing industry. FDI in the food processing industry may be directed toward production facilities to meet the demand expressed in the host countries. FDI in food processing industry may also be intended to source agricultural products from local farmers in some cases.2

FDI in the food processing industry is beneficial for the receiving countries and have many implications for the global food value chain. They create important horizontal and vertical spillovers, help to increase productivity in farm production and solve incomplete contract problems (Gow and Swinnen,1998;Zepeda,2001;Weatherspoon and Reardon,2003;Dries and Swinnen,2004).3 For the host countries, FDI also helps to increase capital invested in the targeted industry or sector. Thus, FDI is important for the global economy, multinational firms and receiving countries.

The food industry is a good case study in the context of FDI. First, barriers to trade in the agri-food sector are very high. The weight/value ratio of agricultural products is high and may represent a substantial shipping cost for these products (Hummels,2010). Second, trade in the food industry is very important in comparison of trade in the primary agricultural sector. For example, agricultural raw materials accounted for only 1.43% of world total export in 2014, whereas food products accounted for 8.61% (WITS data, accessed Nov. 11, 2015). In other words, the composition of global agricultural trade has shifted toward processed food products. Third, the food industry has become more differentiated with the increasing importance of food safety and quality standards. Markusen(1995) noted the presence of multinational firms in industries characterized by specific advantages such as scale economies, imperfect competition, high levels of product differentiation, branding and high value of intangible assets. Antràs and Yeaple(2014) also noted that multinational firms are relatively important in capital-intensive and R&D intensive goods.

In this context, exploring the evolution of FDI in the agri-food sector by investigating factors affecting the decision to invest is of interest. Considering the international dimension of the food processing industry is also relevant because, as noted byHenson and Reardon(2005), the agricultural and food product value chains tend to become global and transcend borders, facilitated by the improvement of communications, transportation and technologies and by liberalization.

2For example, the Chinese agri-food firm Synutra invested in a milk powder plant in France. http:

//www.ouest-france.fr/bretagne/lait-apres-synutra-euroserum-simplante-carhaix-4500060(accessed

Oct. 23, 2016)

3However, FDI may increase market concentration, reduce local companies’ market share and imply

Determinants of FDI and uncertainty in the food value chain

The literature about the emergence of FDI (transfer of capital across countries) has evolved with the literature of international goods trade (Helpman,2006;Antràs and Yeaple,2014). By relaxing capital immobility in the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson (HOS) model,Mundell(1957) explained the emergence of FDI as driven by international differences in rates of return of capital. In fact, not only goods but also production factors may be traded. The second theory is the life cycle theory ofVernon(1966). According to this theory, FDI occurs to meet demand expressed in less-developed countries (where production costs are generally low) after the new product is first introduced in the most-advanced countries. In the transaction cost economy theory, firms become multinationals when certain transactions can be made at lower cost within the company than through other market agents. Rather than using licensing or a foreign distributor, foreign activities generally occur within the firm boundaries (Antràs and Yeaple,2014). The subsequent theory is the Uppsala Model (Johanson and Vahlne,1977), which asserts that firms follow a path where every step provides more market information about a foreign market. Each step is characterized by a different level of commitment in the foreign markets as these markets become increasingly familiar to multinationals firms.

The eclectic paradigm ofDunning(1977) reconciled all the previous theories and summarized the emergence of multinational firms to the possession of the ownership, location and inter-nalization advantages (OLI). The ownership advantages include scale economies, product differentiation, marketing skills, better access to capital, and preferential borrow interest rates. The location advantages include market demand, production and distribution cost, host country competition, and government policy. The internalization advantages require that the ownership advantages are transferable within the firm boundaries.

However, it is surprising that the FDI literature ignored uncertainty. Yet, uncertainty in the economic and institutional environment of the firm is an important factor in the future profitability of any investment decision. This explained why global FDI flows are highly unstable. They have declined by 18% in 2012 and by 16% in 2014 due to political, policy and economic instability (UNCTAD,2014,2015).

Uncertainty influences FDI through two channels. First, uncertainty may influence FDI because for most economic decisions, there is a time gap between the moment the decision is made and the realization of the variable subject to uncertainty. In production theory,Sandmo (1971) asserted that price risk impacts the expected profit from production and alters the predictions of producers because most decisions are made ex ante, after which natural and economic conditions change. Antle(1983) assessed that firms need not be risk averse to be concerned with risk because the latter affects both technical and economic efficiency. The second reason why uncertainty influences FDI is because FDI is an irreversible investment. FDI entails fixed sunk costs, such as communication, administration and transportation costs

(Buckley,1998). Thus, it is valuable for multinational firms to know if they can succeed in a foreign market before actually entering that market. Given this role of uncertainty, multinational firms may not be solely concerned with the traditional comparative advantages presented above. We could observe FDI due to other advantages, such as a low level of risk.4 The food value chain is subject to significant factors of risk, including the price volatility of agricultural products, weather issues, climate change, natural disasters, farmers’ expectations of future prices, rigid short-term supply, contract issues, consumers concerns, the evolution of demand, health issues, trade policy changes, farm policy, and the resources ownership prob-lem (OECD,2010;Boussard,2010;UNCTAD,2014). These uncertainties represent challenges for the food value chain. In particular, demand volatility, output and input price instability can explain most FDI decisions of processors in the food industry.

The supply of agricultural raw materials is volatile due to farmers’ inability to perfectly predict future prices (Ezekiel,1938), the seasonality of production, climate-sensitive and bulkiness characteristics of agricultural production (Chandrasekaran and Raghuram,2014) and farmers’ private information about future production (Hennessy,1996;Van der Vorst and Beulens, 2002). As a result, agricultural raw prices are volatile because the price elasticity of demand of agricultural products is low; consequently, the volatility of the supply of agricultural raw materials is transfered to price. Hence, agricultural input prices are sensitive to crop output, the seasonal characteristics of output and climate conditions. As an illustration of the volatility of agricultural raw prices, we present the FAO food price index in Figure0.25. We see that nominal price is increasing but volatile, especially in the 2000-2020 period. Deflated price is also more volatile in the 2000-2020 period.

For the demand side, the sources of volatility include income shocks and consumers concerns. Income growth and urbanization affect food consumption because as income grows, con-sumers require food products with additional attributes and concon-sumers tastes and standards of products are scalable (Gorbachev,2011). Moreover, as noted byHenson and Reardon (2005), consumer concerns about food safety are still substantial due to food scandals6, in-dustrialization and internationalization of food production, the emergence of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and the environmental footprint of agriculture.

4Note that FDI may be motivated by risk diversification from home to host countries. For example,Wheeler

and Mody(1992) noted that risk averse investors aim to reduce their downside risk by investing in foreign

locations when events across countries do not move in a perfectly synchronous manner. Flamm(1984) noted that ‘’diversification of country risk is an important feature of the investment decisions of multinational firms siting export plants in developing countries”. In addition to cheap labor, country-specific risk motivated the maintenance of a “portfolio of plant locations“.Ramondo and Rappoport(2010) found that it is optimal to open affiliates in economies that are least correlated with world (aggregate) risk, such as small countries.

5The FAO price index is a measure of the monthly change in international prices of a basket of food

commodi-ties (meat, dairy, cereals, oils and fats, and sugar).

6Examples include BSE (mad cow) in the 1990s, Avian influenza (H1N1) in 2003, 2007’s product recall of

the Peanut Corporation of America, 2008 Chinese milk and infant formula scandal, and the European horse meat scandal in 2013 that involved horse meat sold as beef.

Figure 0.2: Annual FAO Food price index 1961-2017, reference year: 2002-2004

Relationship between uncertainty and investment

As previously stated, uncertainty is important to investors due to irreversibility and the fact that economic conditions may change between the moment the decision to invest is made and the realization of the variable subject to uncertainty. The literature confirms this fact and gives a prominent place to adjustment costs7(time gap consideration) and irreversibility in investment decisions. Regarding the impact of uncertainty, a first strand of the literature found that investment may be non-decreasing with uncertainty when the firm is competitive and has constant return to scale and convex adjustment costs (Hartman,1972;Abel,1983). In this literature, uncertainty has a positive effect on the value of a marginal unit of capital and this incites a competitive firm to increase its investment. This result requires the marginal product of capital for this firm to be convex in price (or any other stochastic variable) so that an increase in the uncertainty of price raises the expected return on a marginal product of capital.

In fact, the mechanism through which uncertainty may positively or negatively affect firms is linked to the convexity or the concavity of the profit function (Klemperer and Meyer,1986) or of the marginal product of capital as inHartman(1972) andAbel(1983)’ configuration. We can consider Figure0.3-0.5. Let x be a stochastic variable (price or quantity) following a symmetric distribution with mean ¯x in the interval [xmin, xmax]. We represent the profit function with respect to the stochastic variable in Figure0.3-0.5. We see that risk can affect investment even for risk-neutral firms. In fact, the variance of shock will increase profit if profit is convex with the stochastic variable or π(E(x)) <E(π(x)), will leave profit unchanged if profit is linear

with the stochastic variable or π(E(x)) =E(π(x))and will decrease profit if profit is concave

7Adjustment costs refer to internal costs made by a firm for the new investment to be fully incorporated into

with the stochastic variable or π(E(x)) >E(π(x)).

Figure 0.3: Risk with a convex profit function

Figure 0.4: Risk with a linear profit function

The results ofHartman(1972) andAbel(1983) received some criticism. According to McDon-ald and Siegel(1986), uncertainty makes investment less likely to occur when the firm has the possibility to wait (the waiting option). Sunk costs of FDI have two effects in uncertainty. First, they create a selection of firms that are sufficiently productive to make the investment (as in the theory of heterogeneous firms ofHelpman et al.(2004)). Second, they create a

Figure 0.5: Risk with a concave profit function

reluctance to invest. The possibility to wait until conditions improve in an investment project creates a flexibility in the investment decision and represents an opportunity cost of investing today rather than waiting and keeping ”the option” to invest in the future. The theory of real options finds that this option is sensitive to uncertainty (McDonald and Siegel,1986;Pindyck, 1991;Dixit,1991;Dixit and Pindyck,1994).Bloom(2014) explained this result well. In fact, Hartman(1972) andAbel(1983) assume that the choice of capital accumulation will leave the future marginal revenue product of capital (profitability) unchanged. However, actions taken today influence the returns observed later. Due to adjustment costs, uncertainty makes investors less sensitive to changes in business conditions.

The second criticism came fromCaballero and Pindyck(1996). According to these authors, uncertainty reduces the optimal rate of investment of firms under imperfect competition and when considering aggregate uncertainty rather than idiosyncratic uncertainty. While a positive or negative idiosyncratic shock has a symmetric effect on the marginal product of capital, a negative aggregate productivity shock will lower profit whereas a positive shock will increase profit if entry of new firms is allowed. Then, aggregate uncertainty has asymmetric effect on the marginal product of capital.

The objective of this thesis is to analyze the effect of the relevant sources of uncertainty on FDI in the food processing industry. The studies on this topic are scarce. The goal of this thesis is to fill this gap. In addition, we want to explain the mechanism by which uncertainty affects FDI in the food industry. We use various methodologies and approaches to achieve this. The objective of this thesis is to answer two main questions: i) given the uncertainty, are FDI commitments made late in comparison to export? (as alternative option)

ii) and is FDI in the food processing industry affected by the uncertainty in the upstream agricultural sector? For the first question, we are interested in the temporal dimension (when to invest?). While for the second question, we are interested in the location problem (where to invest?). In fact, multinational companies face both problems in their international strategy. Multinational companies such as Nestlé invest in countries to access foreign consumers and provide products tailored to their specific tastes. On the other hand, some Chinese multinational companies are investing in Europe to take advantage of the comparative advantage of European countries in agricultural production and export their production to China. To this end, this thesis is separated into three chapters. We begin by answering the first question in the first and second chapters of the thesis. The third chapter provides a response to the second question. Ultimately, our interest is to assert whether reducing agricultural value chain uncertainty can attract more FDI in the food processing industry.

Empirical model of the timing of FDI

In the first chapter, we empirically study how uncertainty can explain the timing of FDI in the food processing industry. We want to explain the optimal moment to undertake FDI. The empirical literature on the timing of FDI is relatively scarce, particularly at the industry level. Campa(1993) show that uncertainty about the future exchange rate can deter entry by multinationals, particularly in industries where sunk investments in physical and intangible assets are relatively high. He tests the effects of real exchange rate fluctuations on the number of foreign firms entering the United States during the 1980s. Li and Li(2010) investigate the choice of ownership strategies of multinationals in the face of demand volatility in the manufacturing industries of China. They find that demand volatility makes multinational firms prefer to start internationalization via a flexible strategy before a committed strategy (e.g., a joint venture over a wholly owned subsidiary) and that this relation is reduced in industries with strong growth potential or intense competition. Conconi et al.(2016) argue that uncertainty leads firms to test foreign markets through export before investing there. The time of exporting before FDI depends upon the realization of firm productivity, the fixed cost of FDI and trade costs. The authors use the firm exit rate, country risk index, and expropriation risk as measures of the degree of uncertainty firms face.

However, to the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies have explored the relationship between demand volatility and the timing of FDI in the food industry. It is known fromGorbachev(2011) study that food consumption volatility increases. This is explained by income growth and urbanization that affect consumers requirement of additional attributes of food products and influence consumers tastes and standards of products. Moreover,Henson and Reardon(2005) noted that food consumption are also influenced by consumer concerns about food safety due to food scandals that are unpredictable.

In addition, we want to know if there is other possible sources of uncertainty for FDI in food industry. We also want to know what occurs in terms of FDI in industries oriented toward the export market that are less concerned with the host market demand size or for FDI in market-oriented industries that are more concerned with the economic environment in the host country. Thus, for the food processing, chemical products and transport equipment industries, we assess the impact of demand volatility and other sources of volatility. For example, we want to know if, for a certain type of industry oriented toward exports, a reduction in the export volatility of a country leads to an increase of inward FDI stock in that country.

Our interest in this topic is motivated by the lack of literature empirically assessing the impacts of uncertainty on the optimal timing of FDI. We assume that uncertainty increases the probability of undertaking FDI at some later point. Evidence ofHenderson et al.(1996) in the food industry suggest that multinational firms international strategy is to jump trade barriers to capture a foreign market. For example, they stated that US multinational firms go abroad to reach new consumers and take advantage of growth opportunities unavailable in the US. Thus, the question is whether the fact that realized demand is unpredictable or that there is uncertainty in the host market production deters FDI at the industry level. We follow the literature and test these predictions using duration analysis (Hess and Persson,2012). Export versus FDI under demand uncertainty

In the second chapter, we analyze the trade-off between export and FDI given uncertainty about the size of the market demand using the real options literature. In addition to demand uncertainty, we also consider factors such as trade barriers, risk attitude (aversion to risk) and the competition environment.

The literature on the choice between export and FDI is mainly based on the “proximity-concentration trade-off” model (Brainard,1997;Helpman et al.,2004). This model states that FDI and trade are substitutes with respect to the trade costs and fixed costs of FDI. FDI is substitute to trade in countries with high transport costs and a small difference between FDI and export fixed costs. Brainard(1997) argue that lower trade costs have a positive effect on FDI relative to export sales and that higher FDI fixed costs have a negative effect on FDI relative to export. The firm would choose between proximity (saving on trade costs) and concentration (taking advantage of scale economies). In addition to this result,Helpman et al. (2004) find that a large productivity dispersion of firms has a positive effect on FDI relative to export and that more productive firms use affiliates, intermediate firms use export, and less productive firms serve only the domestic market.

However, the proximity-concentration trade-off model has received criticisms. Later theo-retical developments reveal that the relationship between FDI and trade appears to depend

on market size and the nature of competition between firms (Neary,2009;Mukherjee and Suetrong,2012), the size of trade costs and the possibility to export back (Pontes,2007). Neary (2009) andMukherjee and Suetrong(2012) find that trade cost reduction may encourage FDI for export purposes. Pontes(2007) find that the relationship between FDI and trade cost is non-monotonic; it is positive for low trade costs and becomes negative for high trade costs. Conconi et al.(2016) show that export and FDI may be complementary when considering the dynamic nature of the internationalization process of firms. Firms test foreign markets by exporting before investing to produce abroad. Thus, the decision to engage in FDI after exporting depends upon the realization of firm productivity, the fixed cost of FDI and trade costs.

There is an extensive literature on the timing of FDI decisions. This literature is mainly based on the fact that the relationship between export and FDI depends not only on trade costs and fixed costs but also on the increase in exposure to risk resulting from FDI. The real options model has been extensively used to address this question.Campa(1993) studies the impact of exchange rate fluctuation on the decision to make FDI by firms exporting to the United States. He shows that exchange rate uncertainty increases the waiting option. Rob and Vettas(2003) study the choice between export and FDI with a growing demand. They find that the waiting period before FDI is longer when the cost of investment and the probability that demand growth stops are large and when the cost of exports is small.Pennings and Sleuwaegen(2004) find that the optimal value threshold to switch from export to FDI increases with uncertainty about the project value.

We rely on this literature to assess the optimal moment to undertake FDI in a market served by exports. We add more structure to the investment project value by allowing for imperfect competition. In fact, we consider that multinational firms face local rivals in their host markets. This is a more realistic situation than a monopolist, as was previously assumed by (Pennings and Sleuwaegen,2004). Moreover, we consider product differentiation due to monopolistic advantages of multinational firms such size, technologies and R&D (Markusen,1995). We focus on uncertainty over the host market number of consumers.

Vertical and horizontal FDI with supply and price volatility

In the last chapter, we analyze the trade-off between home and the foreign locations of production given cross-border differences in farm supply volatility while distinguishing between horizontal and vertical FDI. We use theoretical and empirical analyses to study the question of uncertainty in the food processing industry from a supply chain perspective as we consider uncertainty in the upstream sector.

The distinction between horizontal and vertical FDI is central and helps to understand the reason behind the emergence of multinational firms. In fact, FDI takes many forms, including

horizontal, vertical and export-platform FDI. Horizontal FDI refers to the installation of one or more plants in the host market that was previously supplied by exports. Thus, horizontal FDI arises between countries with little difference in factor endowments and country size (Carr et al.,2001). Vertical FDI arises due to factor endowment differences between countries (Elberfeld et al.,2005), which enables the exploitation of factor cost differences between the home country and foreign countries. An example of vertical FDI is when the parent firm is located in a country abundant in skilled labor while the foreign plant is located in a country abundant in a different factor like unskilled labor or arable land.

International flows data strongly support the presence of these different types of internation-alization. For example, almost three-quarters of total sales of foreign manufacturing affiliates of US multinationals is domestic, and the remaining quarter is traded, with one-third of that exported back to the US and approximately two-thirds exported to third countries (Ekholm et al.,2007;Garetto et al.,2016). However, the literature provides no evidence in the food industry.

As horizontal FDI is the predominant form of FDI, vertical FDI is concentrated among large multinational firms (Antràs and Yeaple,2014). Also, the distinction is not always clear because the two types are not necessarily mutually exclusive (Hanson et al.,2005;Neary,2008). They may reinforce each other if the firm wishes both to supply the home market at the lowest production cost and foreign markets to avoid transportation costs. In this sense,Carr et al. (2001) introduce a “knowledge-capital model” that integrates the horizontal and vertical modes of FDI and allows for the exploitation of both plant-scale economies and factor-price differences. A particular case of the knowledge-capital model is the third form of FDI known as export-platform FDI (Ekholm et al.,2007). This strategy allows production in a single country and export back to the home market or to a third country to avoid the replication of fixed costs (Bénassy-Quéré et al.,2001).

This distinction of FDI by type is also central to understanding the role of trade costs in multinational firm activities (Carr et al.,2001). First, trade costs must not be too high to motivate vertical FDI, even between countries with differences in factor endowments, because affiliates’ production of vertical multinational firms consists mainly of intermediate products and is exported to the parent firm, creating intra-firm trade.Antràs and Yeaple(2014) suggest that vertical specialization is more difficult at long distances. Second, trade costs have to be moderate to high to motivate horizontal FDI because horizontal FDI is made in countries previously served by exports and to save on trade costs. Thus, horizontal FDI and trade are substitutes.

In the empirical literature, FDI is determined by country size, relative factor endowment and distance. The theoretical foundation of empirical FDI models relies on the gravity model (Egger and Pfaffermayr,2004;Kleinert and Toubal,2010). In addition to the host market size,

FDI depends on the possibility to supply neighboring markets from the host country (Neary, 2009), the labor endowment and the wage (Billington,1999). Taxation and monetary policy in the home country also play a role (Billington,1999). Medvedev(2012) note that non-trade provisions of regional trade agreements influence FDI. Political stability, an existing colonial relationship, and a common language are also important for multinationals (Du et al.,2008; Castro and Nunes,2013).

However, these studies do not consider risk. This shortcoming has been addressed by the literature interested with exchange rate volatility.Cushman(1988) find that while bilateral exchange rate risk increases a multinational’s overall market risk, in the case where export is allowed, it may increase FDI if risk exposure is negative. Goldberg and Kolstad(1995) find that exchange rate uncertainty may increase FDI by risk-averse United States multinational firms if the exchange rate is correlated with export demand shocks and because FDI, as substitute for exports, reduce the firms’ exposure to risk.

We rely on a more recent literature focused on supply and demand volatilities. Aizenman and Marion(2004) find that uncertainty affects FDI and impacts horizontal and vertical FDI in different ways. This is particularly true now that we know that the two modes do not have the same motivations. They find that demand shocks discourage both vertical and horizontal production modes, that supply shocks discourage vertical FDI and may increase horizontal FDI and that sovereign risk has a more negative impact on vertical FDI than on horizontal FDI. This differential effect arises because by exploiting production cost differences between countries, vertical FDI makes the production process dependent on the economic conditions in all countries where production is located. Ramondo et al.(2013) analyze the proximity concentration trade-off in the context of stochastic productivity. They theoretically and empirically test for a positive impact of production (GDP) volatility on FDI and export resulting from the convexity of the profit function.

We develop a theoretical model and an empirical application about the choice between exporting and horizontal FDI and between domestic production and vertical FDI for the food processing industry that account for uncertainty. There is no consensus in the literature about the sign of the relationship between uncertainty and FDI and it is relevant to analyze this question while accounting for the specificities of the food processing industry. Our theoretical model takes into account the market power of processing firms and agricultural production specificities such as inelastic short run supply and seasonality. In addition, in contrast to previous analyses, we are interested in uncertainty regarding input costs. Moreover, the results of the second chapter regarding trade costs are complemented by the third chapter as we distinguish FDI by type.

0.1

Bibliography

Abel, A. B. (1983). Optimal investment under uncertainty. The American Economic Review, 73(1):228–233.

Adelaja, A., Nayga, R., and Farooq, Z. (1999). Predicting mergers and acquisitions in the food industry. Agribusiness, 15(1):1–23.

Aizenman, J. and Marion, N. (2004). The merits of horizontal versus vertical fdi in the presence of uncertainty. Journal of International economics, 62(1):125–148.

Antle, J. M. (1983). Incorporating risk in production analysis. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 65(5):1099–1106.

Antràs, P. and Yeaple, S. R. (2014). Multinational firms and the structure of international trade. Handbook of International Economics, 4:55–130.

Bénassy-Quéré, A., Fontagné, L., and Lahrèche-Révil, A. (2001). Exchange-rate strategies in the competition for attracting foreign direct investment. Journal of the Japanese and international Economies, 15(2):178–198.

Billington, N. (1999). The location of foreign direct investment: an empirical analysis. Applied economics, 31(1):65–76.

Bloom, N. (2014). Fluctuations in uncertainty. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(2):153– 175.

Boussard, J.-M. (2010). Pourquoi l’instabilité est-elle une caractéristique structurelle des marchés agricoles? Économie rurale. Agricultures, alimentations, territoires, (320):69–83. Brainard, S. L. (1997). An empirical assessment of the proximity-concentration trade-off

between multinational sales and trade. The American Economic Review, 87(4):520–544. Buckley, A. (1998). International investment-value creation and appraisal: a real options approach.

Handelshøjskolens Forlag.

Caballero, R. J. and Pindyck, R. S. (1996). Uncertainty, investment, and industry evolution. International Economic Review, 37(3):641–662.

Campa, J. M. (1993). Entry by foreign firms in the united states under exchange rate uncer-tainty. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 75(4):614–622.

Carr, D. L., Markusen, J. R., and Maskus, K. E. (2001). Estimating the knowledge-capital model of the multinational enterprise. The American Economic Review, 91(3):693–708.

Castro, C. and Nunes, P. (2013). Does corruption inhibit foreign direct investment? Política. Revista de Ciencia Política, 51(1):61–83.

Chandrasekaran, N. and Raghuram, G. (2014). Agribusiness Supply Chain Management. CRC Press.

Conconi, P., Sapir, A., and Zanardi, M. (2016). The internationalization process of firms: from exports to fdi. Journal of International Economics, 99:16–30.

Cushman, D. O. (1988). Exchange-rate uncertainty and foreign direct investment in the united states. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 124(2):322–336.

Dixit, A. (1991). Analytical approximations in models of hysteresis. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(1):141–151.

Dixit, A. K. and Pindyck, R. S. (1994). Investment under uncertainty. Princeton university press. Dries, L. and Swinnen, J. F. (2004). Foreign direct investment, vertical integration, and local

suppliers: evidence from the polish dairy sector. World development, 32(9):1525–1544. Du, J., Lu, Y., and Tao, Z. (2008). Economic institutions and fdi location choice: Evidence from

us multinationals in china. Journal of comparative Economics, 36(3):412–429.

Dunning, J. H. (1977). Trade, location of economic activity and the mne: A search for an eclectic approach. In The International Allocation of Economic Activity, pages 395–418. Springer. Egger, P. and Pfaffermayr, M. (2004). Distance, trade and fdi: a hausman–taylor sur approach.

Journal of Applied Econometrics, 19(2):227–246.

Ekholm, K., Forslid, R., and Markusen, J. R. (2007). Export-platform foreign direct investment. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(4):776–795.

Elberfeld, W., Götz, G., and Stähler, F. (2005). Vertical foreign direct investment, welfare and employment. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 5(1):1–30.

Ezekiel, M. (1938). The cobweb theorem. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 52(2):255–280. Flamm, K. (1984). The volatility of offshore investment. Journal of Development Economics,

16(3):231–248.

Garetto, S., Oldenski, L., and Ramondo, N. (2016). Life-cycle dynamics and the expansion strategies of us multinational firms. Technical report, Boston University mimeo.

Goldberg, L. S. and Kolstad, C. D. (1995). Foreign direct investment, exchange rate variability and demand uncertainty. International Economic Review, 36(4):855–873.

Gopinath, M., Pick, D., and Vasavada, U. (1999). The economics of foreign direct investment and trade with an application to the us food processing industry. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 81(2):442–452.

Gorbachev, O. (2011). Did household consumption become more volatile? The American Economic Review, 101(5):2248–2270.

Gow, H. R. and Swinnen, J. F. (1998). Up-and downstream restructuring, foreign direct investment, and hold-up problems in agricultural transition. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 25(3):331–350.

Hajderllari, L., Karantininis, K., and Lawson, L. G. (2012). Fdi as an export-platform: A gravity model for the danish agri-food industry. Technical report, University of Copenhagen, Department of Food and Resource Economics.

Hanson, G. H., Mataloni Jr, R. J., and Slaughter, M. J. (2005). Vertical production networks in multinational firms. Review of Economics and statistics, 87(4):664–678.

Hartman, R. (1972). The effects of price and cost uncertainty on investment. Journal of economic theory, 5(2):258–266.

Helpman, E. (2006). Trade, fdi, and the organization of firms. Journal of Economic Literature, 44(3):589–630.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., and Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Export versus fdi with heterogeneous firms. The American Economic Review, 94(1):300–316.

Henderson, D. R., Handy, C. R., and Neff, S. (1996). Globalization of the processed foods market. US Department of Agriculture, ERS.

Hennessy, D. A. (1996). Information asymmetry as a reason for food industry vertical integration. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 78(4):1034–1043.

Henson, S. and Reardon, T. (2005). Private agri-food standards: Implications for food policy and the agri-food system. Food policy, 30(3):241–253.

Hess, W. and Persson, M. (2012). The duration of trade revisited. Empirical Economics, 43(3):1083–1107.

Hummels, D. (2010). Transportation costs and adjustments to trade. In Trade Adjustment Costs in Developing Countries: Impacts, Determinants and Policy Responses, pages 255–263. The World Bank.

Johanson, J. and Vahlne, J.-E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm—a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of Interna-tional Business Studies, 8(1):23–32.

Kleinert, J. and Toubal, F. (2010). Gravity for fdi. Review of International Economics, 18(1):1–13. Klemperer, P. and Meyer, M. (1986). Price competition vs. quantity competition: the role of

uncertainty. RAND Journal of Economics, 17(4):618–638.

Li, J. and Li, Y. (2010). Flexibility versus commitment: Mnes’ ownership strategy in china. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(9):1550–1571.

Makki, S. S., Somwaru, A., and Bolling, C. (2004). Determinants of foreign direct investment in the food-processing industry: a comparative analysis of developed and developing economies. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 35(3):60–67.

Markusen, J. R. (1995). The boundaries of multinational enterprises and the theory of interna-tional trade. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(2):169–189.

McDonald, R. and Siegel, D. (1986). The value of waiting to invest. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 101(4):707–727.

Medvedev, D. (2012). Beyond trade: the impact of preferential trade agreements on fdi inflows. World Development, 40(1):49–61.

Mukherjee, A. and Suetrong, K. (2012). Trade cost reduction and foreign direct investment. Economic Modelling, 29(5):1938–1945.

Mundell, R. A. (1957). International trade and factor mobility. the american economic review, 47(3):321–335.

Neary, J. P. (2008). Foreign direct investment: The oli framework. Princeton encyclopaedia of the world economy.

Neary, J. P. (2009). Trade costs and foreign direct investment. International Review of Economics & Finance, 18(2):207–218.

OECD (2010). Managing risk in agriculture. OECD Publishing.

Pennings, E. and Sleuwaegen, L. (2004). The choice and timing of foreign direct investment under uncertainty. Economic Modelling, 21(6):1101–1115.

Phillips, S. and Ahmadi-Esfahani, F. Z. (2012). Inbound cross-border mergers and acquisitions in australian agrifood manufacturing: Macro and industry determinants. Economic Papers: A journal of applied economics and policy, 31(3):337–345.

Pindyck, R. S. (1991). Irreversibility, uncertainty, and investment. Journal of Economic Literature, 29(3):1110–1148.

Pontes, J. P. (2007). A non-monotonic relationship between fdi and trade. Economics Letters, 95(3):369–373.

Ramondo, N. and Rappoport, V. (2010). The role of multinational production in a risky environment. Journal of International Economics, 81(2):240–252.

Ramondo, N., Rappoport, V., and Ruhl, K. J. (2013). The proximity-concentration tradeoff under uncertainty. Review of Economic Studies, 80(4):1582–1621.

Reardon, T., Barrett, C. B., Berdegué, J. A., and Swinnen, J. F. (2009). Agrifood industry transformation and small farmers in developing countries. World development, 37(11):1717– 1727.

Rob, R. and Vettas, N. (2003). Foreign direct investment and exports with growing demand. The Review of Economic Studies, 70(3):629–648.

Sandmo, A. (1971). On the theory of the competitive firm under price uncertainty. The American Economic Review, 61(1):65–73.

UNCTAD (2014). World investment report. UNCTAD (2015). World investment report. UNCTAD (2016). World investment report.

Van der Vorst, J. G. and Beulens, A. J. (2002). Identifying sources of uncertainty to generate supply chain redesign strategies. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 32(6):409–430.

Vernon, R. (1966). International investment and international trade in the product cycle. The quarterly journal of economics, 80(2):190–207.

Weatherspoon, D. D. and Reardon, T. (2003). The rise of supermarkets in africa: implications for agrifood systems and the rural poor. Development policy review, 21(3):333–355.

Wheeler, D. and Mody, A. (1992). International investment location decisions: The case of us firms. Journal of international economics, 33(1):57–76.

Zepeda, L. (2001). Agricultural investment, production capacity and productivity. FAO Economic and Social Development paper, pages 3–20.

Chapter 1

Empirical Analysis of the Timing of

FDI under Risk at the Industry Level

Abstract:This paper examines the relationship between risk and the probability of undertaking FDI using industry-level data. Our objective is to test the role of reducing risk as a motive to attract foreign investments. We aim to analyze industry-level investment decisions and how specific industry characteristics affect these decisions. We test this hypothesis for FDI in food product, chemical and transport equipment industries. We find that high import volatility decreases the probability to make FDI in the food industry and chemical products industry. High output volatility decreases the probability to make FDI in the chemical industry. Export volatility decreases the hazard rate of FDI in the transport equipment industry. Some industries are more influenced by risk than others, and the nature of risk differs across industries.

JEL classification: D43, D81, D92, F21

1.1

Introduction

Data from recent years reveal considerable variability in foreign direct investment (FDI) stocks/flows between countries. Global FDI flows have declined by 18% in 2012 and by 16% in 2014 (UNCTAD,2014,2015) as a result of political and economic instability (global economy fragility, policy uncertainty, geopolitical risks) in the receiving countries. Risk has a large influence on the FDI of multinational firms. For example, data suggest that few exporting firms become multinational firms (Conconi et al.,2016;Gumpert et al.,2016). This results from the fact that FDI encompasses sunk costs that make the investment choice irreversible. Risk also influences international resource allocation when parent firms choose FDI for efficiency-gain purposes or to produce at the lowest costs. In this situation, the cross-country resource allocation may be sub-optimal as risk increases. We observe that risk constitutes a substantial concern for foreign investors and also for the destination countries of these FDI and the global economy.

In this article, we study the timing of the FDI decision, that is, the optimal time to undertake FDI in foreign markets, taking into account the risks in those markets. The starting point is that risk may delay FDI in the receiving countries. The possibility that risk may be a concern for multinational firms has been studied by Aizenman and Marion(2004) who find that supply shocks, demand shocks and sovereign risk discourage FDI.Ramondo and Rappoport (2010) find that risk plays a role in the production location decision and the risk diversification strategy of multinational firms. Other studies have considered the role of variability or risk due to the exchange rate, interest rate, and politics (Cushman,1988; Goldberg and Kolstad,1995;Büthe and Milner,2014). Those studies assess the impact of risk on the level of FDI, whereas studies concerned with the timing of FDI are, for the most part, theoretical analyses (Rob and Vettas,2003;Pennings and Sleuwaegen,2004;Yu et al.,2007). According to the real options model, the decision to make irreversible investment is delayed due to uncertainty, resulting in an option value of waiting (McDonald and Siegel,1986). FDI are irreversible because they encompass sunk costs, and by undertaking FDI, a firm needs to make considerable resources available. Thus, the opportunity cost of undertaking FDI rather than waiting is highly sensitive to uncertainty.

The decision to undertake FDI is influenced by different factors. In the literature,Johanson and Vahlne(1977) note that firms follow a path of internationalization, with each step providing information about foreign markets. Thus, firms start by exporting and make FDI when they have acquired sufficient information about foreign markets.Buckley and Casson(1981) address the decision of multinationals to switch from export to FDI and find that multinational firms switch to FDI when the market demand increases. Brainard(1997) state that costs incurred for export, economies of scale and investment barriers play important roles in this decision. This is known as the proximity-concentration trade-off model. In this model, low trade costs and high firm-level fixed costs have a positive effect on FDI relative to export

sales while high plant-level fixed costs decrease FDI relative to export. Other factors, such as industry-level heterogeneity or elasticity of substitution between varieties, also play a role (Brainard,1997;Helpman et al.,2004).

According to the real options model, another factor is the uncertainty in the investment project. Multinational firms consider uncertainty before they invest because FDI generally involves a higher resource commitment in the local foreign market (Möhlmann et al.,2009). Campa (1993) shows that uncertainty about the future exchange rate can deter FDI entry. Rob and Vettas (2003) study the choice between export and FDI with a growing demand. They find that the waiting period before FDI is longer when the cost of investment and the probability that demand growth stops are large and when the cost of exports is small. Pennings and Sleuwaegen(2004) find that the timing of FDI is influenced by the uncertainty of the value of the investment project. However, there are some results showing a positive effect of uncertainty. Cushman(1988) find that FDI, as a substitute to export, can be increased by exchange rate uncertainty if FDI reduces the firm’s risk exposure in a country previously served by export. Goldberg and Kolstad (1995) also find that exchange rate uncertainty may increase FDI by risk-averse multinationals if the exchange rate is correlated with export demand shocks.

Consequently, it is natural to ask whether and to what extent risk affects FDI entry from an empirical perspective. We explain the probability of observing FDI between two countries in three industries. Because of the interest of countries in FDI, it is important to explore empirically the host market characteristics defining the location advantages of these countries from the foreign investors’ perspective, which can help to attract FDI. Previous studies are limited as they use firm-level data of one particular country. Li and Li(2010) investigate the choice of ownership strategies of multinationals in the face of demand volatility using FDI in the manufacturing industries of China. They find that demand volatility makes multinational firms prefer flexible strategies over committed strategies (e.g., joint ventures over wholly-owned subsidiaries). Conconi et al.(2016) are interested in multinational firms’ export experience before FDI in the context of uncertainty. The authors use the firm exit rate, country risk index, and expropriation risk as measures of the degree of uncertainty firms face. They find that multinational firms delay their investment decisions until they have acquired sufficient export experience when faced with more uncertain conditions. Our model differs from the previous models with respect to the methodology, the type of data used and the measures of risk.

We use duration analysis to investigate the effect of risk on the likelihood of undertaking FDI. Survival analysis has proved to be useful when analyzing the impact of some variables on the length of time before an event occurs (namely, the hazard rate). It has been used in international trade byHess and Persson(2012) and also in the context of FDI timing at the firm level byRivoli and Salorio(1996);Blandón(2001);Raff and Ryan(2008). Conconi

et al.(2016) use survival analysis to incorporate the fact that firms test foreign markets before investing. However, they also use a continuous time Cox survival analysis.Hess and Persson (2012) suggest the use of discrete time analysis for international flows such as trade. We take this recommendation into account, and it is discussed in Section1.3.1.

Moreover,Conconi et al.(2016) use data about Belgian firms to conduct their analysis. We use two sources of industry-level FDI data, EUROSTAT data for the European Union Member States and the BEA (Bureau of Economic Analysis) for the United States. These data are collected for several industries, including the food processing, chemical and transport equip-ment industries. Our database is unique because we are able to collect bilateral data (allowing us to exploit the dimension of the countries of origin and destination), sectoral data as well as annual data on FDI. We also collected data on FDI in European Union Member States and the United States. The choice of countries forming our database may be rationalized as the major global actors of FDI in the food industry are European Union Member States and the United States. We focus our analysis on manufacturing industries, similar toRamondo et al.(2014). The interest in studying this question for different industries is motivated by the fact that comparative advantages are heterogeneous across sectors (Antràs and Yeaple,2014). Thus, we do not expect that all industries will be impacted by risk to the same extent. We will see how the effect of risk on FDI timing changes across different manufacturing industries. We use several variables to capture the degree of uncertainty multinational firms face in our empirical analysis. The computation of the volatility measure is discussed in Section1.3.2. We consider the volatility of output, the volatility of consumption, the volatility of exports and the volatility of imports. The goal is to determine the consequences of these risks on FDI timing. To understand the roles that consumption, production, import and export risk play in FDI timing, we assert that FDI exists under different forms. We distinguish between domestic-oriented FDI and export-domestic-oriented FDI1. In the first case, the main purpose of FDI is to satisfy

local demand, whereas in the second case, the main purpose is to satisfy demand expressed in foreign markets. We also distinguish between FDI motivated by technology-based ownership advantages and FDI motivated by technology sourcing (Driffield and Love,2007). In the first case, multinational firms bring their knowledge and skills to the host countries while in the second case, multinational firms seek to benefit from a technological advantage of the receiving countries.

With these distinctions, our first measure of risk is the market consumption risk, which is particularly relevant for FDI intended to satisfy demand expressed in foreign markets as local demand is hard to predict in foreign markets (Nguyen,2012). Evidence suggests that domestic consumption is volatile, and that this volatility is caused by income shocks and

1According toWorld Trade Organization(1996), FDI of other countries in the United States is mainly

market-seeking FDI and the United States’ FDI in Mexico is mainly export-oriented FDI (Pacheco-López,2005). Relatively open markets tend to attract export-oriented FDI while relatively protected markets tend to attract market-oriented FDI (World Trade Organization,1996).

consumer concerns. For example, income growth and urbanization have been shown to affect consumption (Gorbachev,2011).Galí(1993) study the variability of durable and nondurable consumption. Thus, multinational firms cannot predict the evolution of demand on foreign markets, but this prediction is crucial to reduce the disadvantage of doing business abroad (Johanson and Vahlne,1977).

Production in destination countries is also volatile.Ramey and Ramey(1995) andMalik and Temple(2009) reveal that output can be highly volatile.Ramey and Ramey(1995) find that countries with higher output volatility have lower economic growth. In our context, this production volatility may caused an uncertainty in the technology available in the destination country. However, in industries that are capital and R&D intensive, such as the chemical industry, technology plays an important role. Consequently, production volatility may be an important driver of FDI when multinational firms seek to access a given technology. Thus, we integrate the volatility of industry-level output into our empirical investigation.

Low export and import volatility in a country may be a driver of FDI at the industry level. As stated byEngel and Wang(2011), imports and exports are approximately three times as volatile as GDP. Export volatility influences export-oriented FDI, that is, when multinational firms use export to access neighbor markets of the destination market. This is particularly true when investing in tradable sectors and when the fixed FDI costs are important. This strategy also intends to provide inputs or final goods to the source country via intra-firm trade. For example, some industries, such as transport equipment, electronic and textiles, are export-oriented industries (Antràs and Yeaple,2014)2. Import volatility in destination countries may be evidence that market demand is very volatile. According toFontagné(1999); Pacheco-López (2005), high imports of a particular product by countries is evidence that local firms are not able to satisfy all of the domestic demand. Thus, FDI might be used by multinational firms to fill the local production. To assess the relevance of export and import on the FDI timing, we add export and import volatility to our empirical specification. Our results suggest that high consumption volatility does not reduce the hazard rate, i.e., the instantaneous rate at which FDI relationships start. We explain this by the openness to trade of the targeted industry. In fact, consumption volatility is more harmful for domestic-oriented industries than for trade-oriented industries. The factors that most influence FDI in some sectors may be different from the factors that influence FDI in other sectors. When we control for market size, low import volatility increases the hazard rate of FDI in the food industry. Output volatility reduces the hazard rate of FDI in the chemical industry, and export volatility reduces the hazard rate of FDI in the transport equipment industry. We study consumption uncertainty in addition to production uncertainty, import uncertainty and export uncertainty in the context of the timing of FDI. These factors have not previously been explored in the literature.