Toward a Taxonomy of Key Success

Factors for SME’s in a Changing

Environment

The case of the Luxury Industry

France Riguelle, Didier Van Caillie

HEC School of Management, University of Liège, Belgium e-mails: France.Riguelle@ulg.ac.be, d.vancaillie@ulg.ac.be

Abstract

Considering the multiple challenges that SME’s in the luxury industry have to face in the current fast moving environment, especially the incredible growth of big industrial groups, and the difficulty for SME’s to sustain their position on the market, our paper aims at

proposing a state of the art of key success factors (KSF) for SME’s evolving in this industry. This research is conducted in order to contribute to a better understanding of how SME’s can survive under these conditions, and is based on a critical review of the existing specific literature about KSF’s in a perspective of global performance management. In particular, we focus on SME’s and on their management practices in the luxury industry. We aim to derive a synthetic taxonomy of key success factors for SME’s in the luxury industry from the

specialized literature. In a managerial perspective, this may help them to sustain or to recover their performance in the current changing socio-economic context.

2 Introduction

New challenges, such as the increasing importance of big companies still more proactive in this industry, are shaping tomorrow’s landscape in the luxury industry [1]. Particularly, it becomes more and more difficult for many manufacturing SME’s that are present in this industry since a very long time to stay independent when confrontated to giants that jeopardize them even more with takeovers [2].

Literature dedicated to management practices in this industry has paid attention to each field of management (i.e. marketing and sales, supply chain management, etc.) Some of these areas are tackled more than others, but in general, every scholar focus on the luxury industry as its research object [e.g. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7].

A critical literature review in this very specific field shows a gap and a missing link which may partially explain the independency problem of manufacturing SME’s in this industry, e.g. highlighted by [8]: the absence of a model that gathers and organizes their specific KSF’s along with the “value chain model” [9], and which is built up in a resource-based view perspective [10, 11]; while when doing so, those SME’s could adapt more easily their management practices to their changing environment. The aim of this research is thus to fill up this gap.

The paper is organized as follows. Section II presents the adopted approach and the context in which the research is inscribed. Section III explains the methodology applied for this research. Then, results are presented and discussed in section IV. Section V draws up conclusions and opens to further researches. Finally, section VI presents possible managerial applications.

Context and approach

This explorative study requires a definition of the nature of the firms that we consider, and a clarification of the industrial context in which these companies evolve. Based on the findings from [12] for SME’s and of [13], [14] or [15], e.g., for the concept of luxury we clarify the concept of an SME in the luxury industry as an entrepreneurial manufacturing

company that is organized around its founder’s name, which employs people that share the same vision of traditions coming from the company’s history, and that interact to produce a particular object, which reflects the company’s values. This object is rare and exclusive; it is made of high quality materials and provides to its owner a high added value for which he/she agrees to pay a high price. This object may have a value of use, as well as a symbolic value. At last, it allows the customer to get access to a desired social class and specifically, to a social group.

As, in this paper, we seek to assess the capacity of the small firm to adapt to its changing environment, we focus our attention on three contingent factors which relate to the evolving environment of the firm [12]: the size of the firm, its age, and its industry.

Considering the size, we focus on small and medium firms as defined by the European Commission, i.e. companies with less than 250 people employed [16].

The firm's age relates to its current position in its life cycle such as depicted by Adizes [17]. In this model, also according to Penrose [18], the dynamic of the firm is

articulated in four phases: the creation phase, the growth phase, the maturity phase and the decline phase. As literature on luxury management does not make specifically any difference between these, we do not focus on a phase in particular.

The luxury industry is depicted regarding the Porter's five forces model [19] applied to the current industry situation. Literature shows that barriers to entry are middle to high [2] while suppliers’ power remains low [20, 21]. The customers’ power is steadily

3

increasing regarding the changing consumption behaviours [2]. The threat of

substitutes, especially in “accessible luxury”, becomes still more worrying [21, 22]. At least, competition is really high, in particular for SME’s that must fight against giant firms [2, 8].

Some authors, such as Brun & al. [4] and Caniato & al. [23], underline the importance of identifying KSF's for SME's in the luxury industry. In particular, they discuss the case of supply chain and retail activities. Because our aim is to highlight what can make SME’s in the luxury industry successful in a perspective of global performance management, we need however a broader view of these KSF's.

According to Van Caillie [24], the study of the firm’s performance requires a

transversal view of the firm’s processes through the detailed activities that generate value both externally and internally. He proposes to modelize the company according the Porter’s value chain model [9].

To know which activities generate value, we identify what should be achieved by these activities in terms of key success factors. Indeed, [25] underlines that KSF’s are appropriate to study performance. Moreover, Atamer & Calori cited by [25] show that a KSF is an intrinsic element of the firm’s value chain [9]. Thus, we choose to organize the KSF’s identified within the Porter’s value chain [9].

Concerning the choice of the specific KSF’s for SME’s of the luxury industry, Crutzen [12] presents the characteristics of performing SME’s. In particular, she insists on the

importance of the resources available and their deployment within the company. Moreover, Van Caillie [24] demonstrates that SME’s benefit from fewer resources than big firms. Then, to be sure to meet the requirements highlighted by Crutzen [12], and to know which KSF’s are in essence the most difficult to achieve in order to resist to the power of big firms, we retain KSF’s that are high-demanding in terms of resources (financial, human, and technical resources). Therefore we screen all KSF’s identified for companies of the luxury industry without distinction through the filter of the SME’s business failure prevention model [12].

Methodology

To identify KSF’s for SME’s in the luxury industry, we first examine two major reference books from the professional literature [20, 26] from which we derive nine managerial areas. These areas constitute the basis for further researches in the EBSCO

Business Source Premier data base in order to confirm and expand the series of KSF’s initially

identified in the professional literature. Concretely, we identified human resources management, finance, communication, customer relationship management, distribution, brand, brand extension and retail, innovation, and supply chain management as managerial areas.

Out of the search in the data base, a total of 23 articles are retained, based on their abstract. All of these articles were published between 2005 and 2011. Among these 23

articles, 16 of them are empirical researches. 8 of them are based on a quantitative analysis, 4 on a qualitative analysis, and 4 present both one or more qualitative and quantitative analyses. Moreover, 5 of the empirical researches are conducted within a sample of management or marketing students in different universities, and 5 of them within luxury companies. 44% of these studies have been conducted at least partially in Europe, 19% in America, and 22% in Asia.

The other 7 articles are based on theoretical researches, from which 2 refer to a

literature review. One of these literature reviews uses a manual instead of a theoretical model, i.e. the Oslo Manual. The other 5 articles left present pure constructive theoretical researches.

4

Results and discussion

In this section, we gather KSF’s that are retained as leading to a sustainable long-term performance for SME’s in the luxury industry. We consider these as enabling them to resist to their moving environment: these KSF's are presented through the Porter’s value chain model [9]. They are depicted with respect to their belonging either to support or to primary activities.

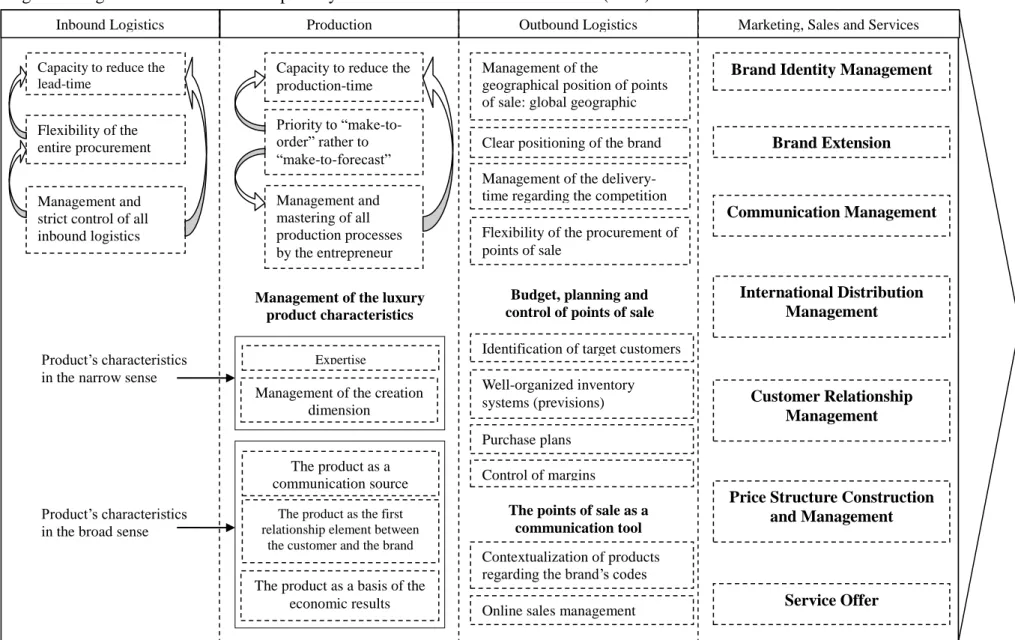

Detailed KSF’s are presented in figures 1 to 3. Figure 3 especially details the specific KSF’s for marketing, sales and services, which emerge from the specific literature as the most crucial activities with reference to the Porter's model [9].

Results

Managing the brand appears really as being at the heart of the global performance management problem in the luxury industry. Indeed, literature highlights that the brand and its management usually appear as the central key elements to master to be successful. As a consequence, activities that are directly linked to brand management (i.e. communication, distribution, customer relationship management (CRM) and appraisal of the environment) are also considered as critical by authors. Specifically, the most widely tackled management problem remains then the importance of the representation of the brand identity through communication activities [20, 26]. Especially, Keller [27] and Tynan, McKechnie & Chhuon [28] underline the prevalence of a well-organized network of points of sales all around the world to ensure brand visibility. They also insist on the communication role of retail.

Simultaneously, several scholars deal with other management issues. In particular, they show the primacy of vertical integration of activities within the value chain. This means a close collaboration with suppliers to protect access to scarce resources [21], as well as the need for flexibility in the supply chain [4]. The same authors underline the importance of managing luxury product characteristics both in a narrow and in a broad perspective. Product characteristics in a narrow perspective refer to the characteristics of the product by itself (materials, quality, etc.), while product characteristics in a broad perspective refer to elements that are engendered by the product (i.e. the product as its first source of communication). It is thus imperative to keep the know-how into the firm to be able to manage all of these

elements.

In the continuity of these considerations, the question of innovation remains also of a considerable importance.Becheikh, Landry & Amara [29] insist on the ability of innovating both in products and in processes. Then, Caniato & al. [23] show the prevalence of the retention of scarce resources within the company to sustain innovation. This is aligned with the KSF referring to the retention of the know-how within the firm that the same authors identify.

Discussion

We select a series of KSF’s that appear as relevant as explained in section II for the socio-economic context in which SME’s in the luxury industry currently evolve.

Nevertheless, KSF’s are by nature influenced by contingent factors such as the firm size, its age and its industry or even, its sub-industry. Thus, KSF’s that we identify and select, even if transversal, remain global. Indeed, they may differ considering the different situation of each company in terms of its internal and its external environments.

Moreover, the literature on KSF’s in this industry related to primary activities – and in particular the literature regarding marketing and sales (i.e. literature on brand management, communication and retail) – is far more important than on other fields of management such as human resources management, financial management, etc. To assess the relevance of the results, an empirical validation could be conducted.

5 Ge ne ra l and Fi na nc ial Mana ge ment Huma n Resour ce s Mana ge ment P roc ur ement R ese arc h and De ve lopm ent Fin an cial Ma n ag em en t Ma n ag em en tMa n ag em en t G ene ra l M ana g em

ent Management and communication of the

company’s culture among all firm’s actors Performing information system regarding the firm’s need Creation of collaborating networks with competitors to share experience Capacity to generate important margins on a few products Capacity to determine reasonable salaries for managers and

employees

Capacity to remain independent from the market pressure Capacity to realize consequent investments that will yield cash flows in the long run

Employment stability – low personnel turnover

Management of the sales staff: training and evaluation

Hiring of staff from outside of the luxury market for new ideas Training the staff for communication

Hiring of staff from other luxury brands for their experience

Continuous staff training

Staff evaluation and motivation: individual and/or global sales commissions, and special bonus if objectives achieved

Product innovation

Process innovation

Conservation of the industrial and

manufacturing know-how within the company

Protection of the access to rare resources Integration of important suppliers into the whole value chain

6

Inbound Logistics Production Outbound Logistics Marketing, Sales and Services

Capacity to reduce the production-time Priority to “make-to-order” rather to “make-to-forecast” Management and mastering of all production processes by the entrepreneur Capacity to reduce the

lead-time

Flexibility of the entire procurement line

Management and strict control of all inbound logistics operations

Management of the luxury product characteristics

Product’s characteristics in the narrow sense

Expertise

Management of the creation dimension

Product’s characteristics in the broad sense

The product as a communication source

The product as the first relationship element between

the customer and the brand

The product as a basis of the economic results

Brand Identity Management

Brand Extension Management Communication Management International Distribution Management Customer Relationship Management

Price Structure Construction and Management

Service Offer Management of the

geographical position of points of sale: global geographic coverage

Management of the delivery-time regarding the competition Flexibility of the procurement of points of sale

Clear positioning of the brand

Budget, planning and control of points of sale

Identification of target customers Well-organized inventory systems (previsions) Purchase plans Control of margins

The points of sale as a communication tool

Contextualization of products regarding the brand’s codes Online sales management Figure 2. Organized KSF's within the primary activities of the Porter's value chain (1998)

7 Figure 3. Detailed KSF's for the Marketing, Sales and Services function

Price alignment with the customers’ perception of the product value (unique price, except transport and fees)

Offer of a purchase experience which is aligned with the brand identity and the value perceived by the customer Mastering of the international distribution channels Management of particular duty-free systems Fight against counterfeit and parallel markets Brand competition management Brand identity reflection Generation of emotions, frames of mind, attitudes Visual impact Integrate socio-cultural differences within the communication strategy Study of the communication efficiency upon the customer Construction of the idea that the company is the leader in innovation in its sector Capacity to invest huge amounts to extend the brand

Capacity to propose directly a wide product range

Capacity to grant time to the customer to convince him/her of the extension’s value

High coherence between all lines and the brand identity/values Brand identity recognition by all members of the firm and by everyone (customer and circle) Brand identity alignment with the trends

Products and services design aligned with the brand identity Brand identity differentiation

Coherence between the price and the brand identity

Coherence between the strategy and the brand identity Brand Identity Management Brand Extension Management Communication Management International Distribution Management Customer Relationship Management Price Structure Construction and Management Service Offer “Basic contract” definition with the customer Dynamic segmentation development Experience offer next to the product itself (events and education management around the product, individualistic characteristics management, and customer’s aesthetic perception management) Comprehension of customers’ attitude toward the brand Measurement of the value of the brand for the customer

8

Conclusions and further researches

Through a critical review of the literature concerning the management of firms (especially the smallest ones) in the luxury industry, we identify a major gap regarding the difficulties that SME’s of this sector face in the current socio-economic context: the absence of a global taxonomy of KSF’s that could help them to tackle changing elements in their internal and external environment. In order to fulfil this gap, our article proposes a selection of KSF’s identified specifically by the literature as critical for SME’s in the luxury industry, and organized around the Porter’s value chain [9].

The following major elements result from this analysis:

1. A SME in the luxury industry has to reconcile its strategy and its staff around the same long term vision and this vision has to be aligned with the brand identity. Moreover, everyone should adhere to it and goal congruence has to be realized round and around this alignment.

2. This identity has to take into account the evolution of the company’s environment, even if it is built upon the historical credentials of the firm.

3. The ability to understand customers’ wishes and requirements is compulsory for the firm in order to create a particular long lasting relationship with them. Therefore the firm should offer personalized products and services, which are aligned with the brand identity.

4. To reach these customers, it is crucial to deal correctly with communication issues. Indeed, they constitute the best way to vehicle the brand identity to the customer. 5. Ultimately, vertical integration in the supply chain (inbound and outbound) within the

firm is the best way to meet these former requirements. This can only be realized by the mastering and the retaining of know-how within the firm. This requires developing strong partnerships with suppliers to guarantee to the firm the access to scarce

resources on the one hand, as well as with retailers that make the link between the firm and the customer on the other hand.

Limitations and further researches

Being based on a broad literature review, the taxonomy that we propose requires undoubtedly an empirical validation to be completed and/or corrected. This is clearly the aim of further researches.

In addition, different taxonomies have to be developed to assess the different

contingent possibilities that SME’s in the luxury industry could have to tackle. These could be assessed regarding the specific sub-industry, the position of the firm within its life cycle, its size, or the design of its management (family business, small group of investors, etc.)

At last, it appears useful to deal with the necessary deployment of resources within SME’s in the luxury industry by using the resource-based theory [10, 11] articulated around the Porter’s value chain as presented here. This could be done in a timeless approach on the one hand, and then regarding the firm’s life cycle steps on the other hand. This approach could lead to find out more dynamic key performance indicators for SME’s in the luxury industry.

Possible managerial applications

The taxonomy that we develop may be considered as a basic material for managers of SME’s in the luxury industry, because it provides a good overview of the most critical issues to tackle in the current socio-economic environment. These KSF’s are then a guideline for

9

managers in small firms to check whether they meet – or not – the basic conditions leading to a long-term sustainable performance.

References

[1] Roux, E. & Floch, J.M. (1996), Gérer l'ingérable: La contradiction interne de toute maison de luxe, Décisions Marketing, 9, 15-23.

[2] Eurostaf (2011). Le marché mondial du luxe et ses perspectives. Paris: Les Echos.

[3] Vickers, J.F. & Renand, F. (2003), The Marketing of Luxury Goods: An exploratory study - three conceptual dimensions. The Marketing Review, 3, 459-478.

[4] Brun, A. & al. (2008), Logistics and supply chain management in luxury fashion retail: Empirical investigation of Italian firms, International Journal of Production Economics, 114, 554-570.

[5] Atwal, G. & Williams, A. (2009), Luxury brand marketing - The experience is everything!,

Journal of Brand Management, 16, 338-346.

[6] Cailleux, H., Mignot, C. & Kapferer, J.N. (2009), Is CRM for luxury brands?, Journal of

Brand Management, 16, 406-412.

[7] Dion, D. & Arnould, E. (2011), Retail Luxury Strategy: Assembling Charisma through Art and Magic, Journal of Retailing, 87: 4, 502-520.

[8] Lipovetsky, G. & Roux, E. (2003), Le luxe éternel. De l'âge du sacré au temps des

marques, Paris: Gallimard.

[9] Porter, M.E. (1998), Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance, New-York, NY: Free Press.

[10] Wernerfelt, B. (1984), A Resource-Based View of the Firm, Strategic Management

Journal, 5, 171-180.

[11] Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of

Management, 17: 1, 99-120.

[12] Crutzen, N. (2010). Essays on the Prevention of Small Business Failure: Taxonomy and Validation of Five Explanatory Business Failure Patters (EBFPs), in CeFiP-KeFiK Academic

Awards 2009. Bruxelles, Belgique: De Boeck & Larcier.

[13] Berry, C.J. (1994). The Idea of Luxury. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [14] Vigneron, F. & Johnson, L.W. (2004), Measuring perceptions of brand luxury, Brand

Management, 11: 6, 484-506.

[15] Mortelmans, D. (2005), Sign values in processes of distinction: The concept of luxury,

Semiotica, 157: 1-4, 497-520.

[16] European Commission. (2003), Recommandation de la Comission du 6 mai 2003

concernant la définition des micro, petites et moyennes entreprises, Journal officiel de l'Union

Européenne, Recommandation 2003/361/CE.

[17] Adizes, I. (1979), Organizational Passages: Diagnosing and Treating Life Cycle Problems in Organizations, Organizational Dynamics, 9, 3-25.

[18] Penrose, E.T. (1952), Biological analogies in the theory of the firm. American Economic

Review, 42, 804-819.

[19] Porter, M.E. (2008, January), The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy. Harvard

Business Review, 25-40.

[20] Chevallier, M. & Mazzalovo, G. (2008). Luxury brand management: a world of

privilege. Singapour : Wiley.

[21] Kapferer, J.N. & Bastien, V. (2009a), The specificity of luxury management: Turning marketing upside down, Journal of Brand Management, 13, 311-322.

[22] Allérès, D. (2006). Luxe…métiers et management atypiques. 2nd Edition. Paris: Economica.

10

[23] Caniato, F. & al. (2009), A contingency approach for SC strategy in the Italian luxury industry: Do consolidated models fit?, International Journal of Production Economics, 120, 176-189.

[24] Van Caillie, D. (2001), Principes de comptabilité analytique et de comptabilité de

gestion, Liège, Belgium: Les Editions de l'Université de Liège.

[25] Verstraete, T. (1997), Essai de conceptualisation de la notion de facteur clé de succès et de facteur stratégique de risque? VIe conférence de l'Association Internationale de

Management Stratégique, Montréal.

[26] Kapferer, J.N. & Bastien, V. (2009b), The luxury strategy: Break the rules of marketing

to build luxury brands, London, United Kingdom: Kogan Page.

[27] Keller, K.L. (2009), Managing the growth tradeoff: Challenges and opportunities in luxury branding, Journal of Brand Management, 16, 290-301.

[28] Tynan, C., McKechnie, S. & Chhuon, C. (2010), Co-creating value for luxury brands,

Journal of Business Research, 63, 1156-1163.

[29] Becheikh, N., Landry, R. & Amara, N. (2006), Lessons from innovation empirical studies in the manufacturing sector: A systematic review of the literature from 1993–2003,