HAL Id: hal-03048334

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03048334v2

Preprint submitted on 8 Apr 2021HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Risk Perception Biases and the Resilience of Ethics for

Complying with COVID-19-Pandemic-Related Safety

Measures

Bako Rajaonah, Enrico Zio

To cite this version:

Bako Rajaonah, Enrico Zio. Risk Perception Biases and the Resilience of Ethics for Complying with COVID-19-Pandemic-Related Safety Measures. 2021. �hal-03048334v2�

Title

RISK PERCEPTION BIASES AND THE RESILIENCE OF ETHICS FOR COMPLYING TO COVID-19-PANDEMIC-RELATED SAFETY MEASURES

Authors

Bako Rajaonah1, Enrico Zio23 Affiliations

1Laboratory of Industrial and Human Automation control, Mechanical engineering and Computer Science (LAMIH UMR CNRS, 8201), Université Polytechnique Hauts-de-France, Valenciennes, France

2Centre de Recherche sur les Risques et les Crises (CRC), MINES ParisTech/PSL Université Paris, Sophia Antipolis, France.

3Department of Energy, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy. E-mail addresses

Dr. Bako Rajaonah: bako.rajaonah@uphf.fr

Professor Enrico Zio: enrico.zio@mines-paristech.fr; enrico.zio@polimi.it Corresponding author

Dr. Bako Rajaonah bako.rajaonah@uphf.fr

LAMIH, Université Polytechnique Hauts-de-France, Campus Mont Houy, Valenciennes, F-59313

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised discussions on ethics for individual and social resilience. This paper dissects the cognitive biases and heuristics, affective influences and social and cultural factors which impact on the COVID-19-related risk judgments and the compliance with protective behaviors. The analysis shows that these factors may distort people’s mental models of risk—including their individual and shared moral values—as well as their confidence and trust related to distinct stakeholders involved, such as government, science, the health system, vaccination, etc. This leads to an innovative articulation between risk education and communication on the one side, and the resilience of moral values, mental models of risk and trust on the other side. The objective is to increase people’s understanding and acceptance of the authorities’ recommendations in order to enhance social resilience, not only during the pandemic, but also in view of future disasters. We conclude by discussing the need for a framework that integrates the resilience of ethics and ethics of resilience for

disaster management, which should include the culture and societal aspects.

KEYWORDS

1. MOTIVATION

After more than one year of pandemic, nearly three million deaths1 and considerable socio-economic damages in the world, we extend the short communication written in April 2020 during the “first wave” of the pandemic2 to examine the need for a resilient ethic and a deep change of people’s moral values, to fight the pandemic. The paper goes more thoroughly in exploring the relationships between risk judgment in the context of the pandemic and the related risk decision-making which the risk judgment informs. The goal is to draw insights from the influences of biases, heuristics, personality and social factors on risk perceptions, and their impacts on risk decisions, to provide communication guidance so as to adjust guiding values. The next section goes on to discuss these influences. Section 3 takes them into consideration to provide assets for communication and education for resilient ethics. The last section concludes the paper with reflections on the aspects related to resilience.

2. INFLUENCES ON RISK JUDGMENTS AND RISK DECISIONS

First, for the purpose of this paper, we choose the definition of Huang to define risk: it is “a scene in the future associated with some adverse incident” [1]. Next, we recall that in Decision Science, a bias is defined in comparison with normative, rational reasoning, whereas heuristics are adaptive mental strategies, a shortcut that facilitates judgment and decision processes in making sense of the world, with small effort and time costs[2]. Most initial experimental studies of biases and heuristics in judgment under uncertainty are detailed in [3,4,5]. Table 1 presents those we think relevant in the context of the pandemic, but also other sources of influence such as personality and social factors, through the lens of the book by Glynis Breakwell, The Psychology of Risk [6].

Notice that even though these influences are here categorized in terms of cognitive,

personality, affective, and social factors for their readability, in fact, they interact each other and provide different levels of explanation from the individual to the societal levels, as emphasized by Breakwell. Through some examples from COVID-19-related scientific literature, we examine those influences on individuals perceived risk of the pandemic and their protective behaviors.

1 https://covid19.who.int/

Table 1 Cognitive, personality, affective, and social factors influencing risk judgment and

decision-making, according to Breakwell [6]. The factors are in italics.

Cognitive Factors

Availability heuristic: Tendency to assume that the frequency or the probability of an event is greater

if people can easily remember an instance of the event (p. 87). It may interact with the confirmation

bias, i.e. to favor paying attention to information that confirms existing hypotheses or beliefs (pp. 108–

109).

Anchoring bias: Tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered (the anchor)

about a hazard (p. 90).

Representativeness heuristic: Tendency to assume that the probability that an object A belongs to a

category B (categorical judgment) is greater if A resembles B in some fashion (p. 86).

Optimistic bias: Tendency to believe to be less likely to experience negative events, and more likely to

experience positive events, than other people (p. 91).

Mental model of risk: A system of beliefs, feelings and attitudes that the individual holds about the risk

(p. 16), which can influence the way people use information and bring into play their heuristic biases (p. 103).

Personality factors

Perceived self-efficacy and locus of control: Representation of how much control individuals believe

they have over they do or what happens to them (p. 63).

Affective factors

Affect heuristic: Refers to the influence of the affect associated with the object of risk judgment and

decision-making (p. 124, p. 131).

Feeling of risk: Refers to the primacy of emotion in the response to the hazard (p. 123). Social factors

Group norms: Perceived norms of the group to which the individual belongs to (p. 113). Cultural biases: Attitudes and beliefs shared by a group (p. 80).

Social trust: Comprising public trust (i.e. the amalgamated feelings of trust towards all societal

institutions and leaders, the diffuse communal acceptance of the values of the system, p. 158), institutional trust (i.e. the general feeling of trust about a particular organization or social category, p. 109), and specific trust (i.e. the acceptance of the morals and feeling of confidence in a particular institution as it deals with a specific issue at a single time, p. 109).

2.1. Availability Heuristic

The study of Rosi et al. carried out in Italy between 9 April and 3 May 2020, with 1765 participants aged from 18 to 80 years [7], shows that experience with the disease among their relatives, friends or acquaintances was a predictor of perceived vulnerability for all the participants, except for those aged over 70: this was interpreted as the nonuse of the

availability heuristic by the older people because of possible cognitive resources reduction. Regarding this heuristic in general, the more information is repeated, as it is the case for misinformation spread over social networks regarding the COVID-19 topic, the more it is available and easily recalled; still, many who express themselves on this topic are themselves victims of the bias of ultracrepidarianism, that is that they give their opinion and advice without sufficient knowledge of the situation and topic [8]. The result of the use of the

availability heuristic is to miss the relevant information for correct assessment of risk. For example, it can affect attitudes towards vaccination: the results of two studies carried out by LaCour and Davis, with 227 recruited among MTurk workers [9], showed an effect of information availability on vaccine skepticism, in interaction with the affect heuristic, precisely the negativity bias: individuals based their judgment on only the negative information about vaccination, such as the side effects, rather than taking the time in analytical reflection.

2.2. Anchoring Bias

The availability heuristic may interact with the anchoring bias. A French survey carried out in April 2020 with 1566 participants3, showed that a quarter of the respondents thought that the COVID-19 death rate was similar to that of the seasonal flu; about a third of the respondents perceived less risk to be infected by the Coronavirus and around a third thought to have no serious consequences in case of having the disease. The authors of the study interpreted the results in terms of anchoring bias: the flu was the anchor in respondents’ risk judgment. The supposed similarity between the two diseases had reassured people at the beginning of the pandemic when information from political and scientific authorities were too fragmented; some respondents had thus held on to this comforting information and used it in their risk judgment. The study carried out in March and April 2020 in Italy by Guastafierro et al. with participants older than 60, showed that they perceived less risk to contract the Coronavirus compared to perceived risk related to flu and cancer [10]. This might also be interpreted in terms of anchoring bias, but in interaction with perceived control: Guastafierro et al.

hypothesized that the results could be related to the perception of control, due to the fact that the study was carried out during the confinement: the respondents felt safer and perceived relatively low level of risk.

2.3. Confirmation Bias

This bias, like the availability heuristic and the anchoring bias, may also lead to an incomplete assessment of the situation: people tend to search for, select, interpret and

remember only the piece of information that is congruent with their expectations and beliefs. They, then, use this information to confirm or reject their preferred hypothesis; for instance, that the COVID-19 disease was a form of flu, in the earlier stage of the pandemic [11].

3 https://theconversation.com/covid-19-et-biais-dancrage-quand-notre-cerveau-nous-empeche-de-prendre-la-mesure-du-risque-141390 (accessed November 2, 2020)

2.4. Representativeness Heuristic

It appears when we believe than a particular group is unlikely to be infected by the COVID-19 virus or to believe that asymptomatic people represent a “mild” case, which may lead to misperceptions of virus transmissibility [12].

2.5. Optimistic Bias

It may be the strongest bias that could most explain the observed persistence of attitude and behavior concerning self and others’ protection after more than one year of pandemic and serious worldwide socio-economic damages. This bias was observed by Druica et al. [13] through a survey carried out in March 2020 in Romania and Italy: in both countries, the respondents underestimate their likelihood to be infected comparatively to the likelihood assigned to others. However, one of the hypotheses was that Romanians would show a stronger optimistic bias than Italians did, because at the time of the study the pandemic severity was high in Italy: the result does not confirm this hypothesis, in the sense that the observed difference was slight. This may be explained by the fact that the optimistic bias was measured with two questions asking about the perceived likelihood that an infection by COVID-19 could happen to the respondent (i) and to another person (ii), the comparison not being between Romanians and Italians. Another example of optimism bias during the

pandemic is provided by the study carried out in March 2020 in Poland with students, by Dolinsky et al. [14]: they showed that men were more sensitive to the bias than women were, but both populations were globally optimistic regarding the perceived likelihood to become infected, comparatively to the likelihood for others of the same sex in their class. It is worth noticing that the optimistic bias was measured three times: before the first case announced in Poland, after the first case revealed by the Minister of Health and after several reported cases in Poland plus the reports of deaths in Europe. Even though perceived risk to fall ill were higher for the third measures than the first two ones, the optimism bias remained over the three measures. This example shows that the optimism bias is a robust phenomenon.

Moreover, as it was shown by Weinstein, the optimism bias may be influenced by perceived controllability [5] and perceived self-efficacy [15].

The belief that we are less at risk than others may very well explain the noncompliance or partial compliance with preventive measures such as mask wearing, social distancing and vaccination: we let others, whom we think being more at risk than we are, adopt these measures, and the fact that we believe we have some control on our own health may lead us

to determine which guidelines are better for us and, thus, select the ones that suit to our convenience.

2.6. Affective Factors

Affective reactions are “inescapable” and would be the very first reactions that would guide information processing, providing the emotional component of judgment: people first “feel” the information from the environment, before they analyze it [16,17]. This is because of the human mind’s experiential System 1, which processes information quickly, automatically, without effort, differently to the analytic System 2 [18]. COVID-19-related information does not escape such processing of information, with little room being left for a critical analysis of the huge quantity of information daily flowed by social media. This may explain the

interaction with the availability bias and the anchoring bias, especially when prior

information is associated with a strong emotional charge. The study carried out in April 2020 by Vacondio et al. [19] with students from United Kingdom, Italy and Austria showed that worry (measured through the combination of worry about the disease, public policies, and media communication) was a strong predictor of COVID-19 related perceived threat. The study also showed that both perceived threat and worry well predict self-reported preventive behavior.

2.7. Social Factors

Even though people are not sensitive to either cognitive biases or affective biases, they heavily rely on social norms, sometimes independently of perceived risks. For example, Nakayachi et al. showed that wearing masks in Japan relies more on the social norm itself rather than on risk reduction intention [20]. Other group and community effects, as well as cultural biases had been observed since the beginning of the pandemic: risk perceptions depending on the political partisanship [21]; promotion of attitudes such as ageism [22]; mask wearing in altruistic communities [23] or the contrary in anti-quarantine groups [24]; social distancing behavior in risk-averse countries [25]; attitudes towards vaccination depending on political affiliation [26].

Social media play an important role on shared beliefs. For example, the study by Dinga et al. [27], with around two thousand Cameroonians and using the tool developed by WHO to analyze vaccination hesitancy4, showed the impact on vaccine hesitancy of negative

4https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesit ancy_final.pdf

information disseminated through the Internet, about COVID-19 vaccination; the results also showed that hesitant individuals wondered about the pharmaceutical industry’s true interests.

2.8. Trust

Last trust is often referred to in the literature about the measures against the pandemic. The analysis by Schmeltz of a survey carried out in Germany from 29 April to 8 May 2020 with 4799 participants [28] showed a high overall agreement with preventive measures such as tracing app, vaccination, mask wearing, travel limitations, and contact restriction, whether voluntarily or enforced, when the government was perceived as trustworthy, and the less the respondents trusted the government, the less they agreed with enforced measures. The study carried out with 5995 participants from France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States, from 20 March to 10 April 2020, showed that the respondents’ intention to install a contact-tracing app on their phone decreased when they less trusted the government “to do what is right” [29]. Trust has also an impact on intention to uptake the COVID-19 vaccine, for instance, trust in the health system [30], trust in health care professionals and trust in science [31], trust in vaccine manufacturers [32], and trust in the effectiveness and safety of vaccines [33].

Finally, the role of social norms and culture in trust is also important: depending on their cultural group, people may choose which source to trust and, thus, what to fear [34]. It is important to underline that trust has two aspects: trust as a feeling that predisposes to action, which can be related to confidence, and trust as reliance on the trusted party, that is, an engagement in action motivated by the belief that the trusted party will come up to my expectation [35]. Hunyadi thinks that the literature on social trust relates more often to the feeling of confidence than to trust strictly speaking. Even though confidence has an important role in the motivation to engage in action, the difference is huge: on one side, confidence relates to judgment, on the other side, trust relates to an engagement in action.

In the context of the current pandemic, both confidence and trust may not well be calibrated to behave appropriately with respect to the authorities’ protective strategies.

2.9. Overall View

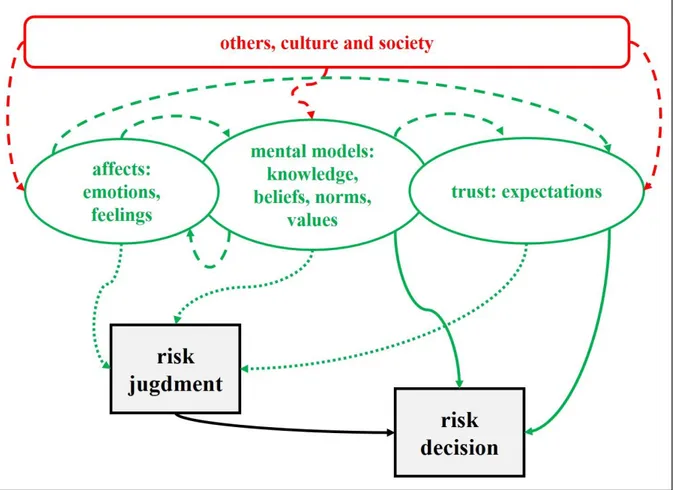

Figure 1 shows the various influences on both risk judgment and the related risk decision-making. Heuristics do not appear in the Figure because they are strategies intrinsic to

judgment. Risk judgment is influenced by (i) affective factors (e.g. feeling of confidence); (ii) mental models of risk, including knowledge (e.g. of virus transmissibility), beliefs (e.g. self-efficacy), social and cultural norms (e.g. attitude towards mask wearing) and moral values (e.g. altruism); and (iii) trust as an engagement in action (e.g. intention to get vaccinated).

Figure 1 Influences of cognitive, affective and social factors on risk judgments and risk decisions. Influence

among influences is in broken line, influence on risk judgment in dashed line and influence on risk decision in solid line.

Risk decisions with regard to the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic by the lay public concerns mask wearing, physical distance keeping, contact tracing app usage, vaccination, movement restriction, lockdown acceptance. Such decisions cannot be made on the impulse but are rather taken after careful thought based on information received, which means that risk decision in the context of the pandemic relies directly on risk perceptions, mental models and trust, and not on confidence.

This leads us to focus risk communication on mental models of risk and trust. Why mental models? The goal of risk communication is to change individuals’ view of risk, and this view is generated by their mental model of risk, which is “a system of beliefs (which can include explanations) and attitudes, with their affective connotations, that the individual holds about the risk” ([6], p. 147). According to Fischhoff, risk communication consists in filling the gaps in the mental model with regard to risk understanding, reinforcing correct beliefs, and

correcting misconceptions [36]. And why trust?Working on confidence and trust is one of the goals of COVID-19-related risk communication [37,38,39]. It is interesting to note that mental models and trust have a common denominator, namely the beliefs, including shared beliefs, held by individuals: the mental “ingredients” of trust are beliefs, expectations, evaluations, goals and motivations [40].

3. RISK COMMUNICATION AND RESILIENT ETHICS

Social resilience for disaster risk reduction can be defined as the capacity of groups and communities to prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters [41]. The challenge of risk communication is here not to just change individuals’ attitude and behavior until the COVID-19 pandemic is mastered, but to change them in a durable way to better face future social crises of various kinds. Therefore, besides working on mental models of risk, trust and confidence, communication should also work on moral values, which is another influence on the individuals perceived right way to behave [42]. Clearly, social resilience relies on groups and communities, but also on their members as individual responsible moral entities who are distinct from each other but influence each other within a given group or community:

therefore, social resilience goes through resilience of ethics, more precisely through adaptation of moral values. Moral values are included in mental models (Figure 1), but we consider them here separately to better highlight them. Then, we deal with mental models and trust, working on them also contributing to the resilience of ethics.

3.1. Moral Values

Communication must be persuasive to make people see the hazard in a different way, but also educative to induce durable changes in behavior [6,43]. Civic education programs could help increase civic engagement, which will be beneficial in the long-term [44]. Message design should be bidirectional and collaborative between government officials, experts and the public at large to acknowledge their motives, for the two formers, and their needs, for the latter [39,45], and also to avoid discordance between messages. The efficacy of draft

messages should be tested [46]. Besides reinforcing social norms that influence individuals by social pressure, risk communication should also work on moral obligation that is an internal constraint [47]. Messages should, thus, contain some kinds of moral lessons addressing both individual and shared social and moral values, to really make messages an opportunity of attitude and behavior change: advocating altruism and pro-social behavior, emphasizing the effectiveness of protective measures at both personal and societal levels, as well as the sense of sacrifice for the greater benefit of society [48]; emphasizing on a shared sense of identity, as well as the sense of cooperation [49]; stressing preventive measures as common goals to be collectively pursued [44].

Repeating messages over and over is a good strategy to avoid familiarization with risk, which induces less perceived health risk and, thus, increases nonprotective behaviors [50], but it should also serve to avoid discouragement of people who make sacrifices but, when they observe that other people “don’t bother,” they may feel unfairness and become less

cooperative [51]. Messages encouraging people to maintain their efforts are, thus, necessary. Communication should make the public aware of the impacts of the behavior of a handful of individuals on the whole society5, for instance, the extreme exhaustion of healthcare workers, the despair of people who had lost their job, the increasing poverty: in short, all aspects of the socio-economic fallout. Looking at these societal impacts, defending the value of individual freedom, for example, through organization of, or participation in public demonstrations against COVID-19 restrictions may be perceived as insulting with regard to the millions of deaths.

However, values such as altruism are not enough. The imperative of responsibility of Jonas considers that the humans are responsible for their action regarding the future of humanity [52]: education should also include that we are responsible “for and to a distant future,” and behaviors towards the compliance with protective measures are part of the respect for humanity.

3.2. Mental Models of Risk

Firstly, assessing the mental models of the COVID-19 pandemic (or any further social crisis of whatever nature) held by people is required to identify gaps and misperceptions, to enable designing relevant communication. Such models can be examined through interviews

beginning with a question like “what do you know about,” and continue with more specific

questions [53]. Knowledge about the COVID-19 disease, especially the mechanisms of transmission and infectiousness, helps people to be more reflective in their judgments and use less heuristics [54]. One way to enhance individuals’ mental models of risk is to provide them with the tools to better understand risk and its management. In the context of the present situation, Donnarumma and Pezzulo5 suggest new educational strategies that make available to the public the relevant knowledge on cognitive and social sciences—e.g. regarding cognitive biases—in order to help them make informed decisions; providing statistic tools is also relevant, for example, to understand the concept of exponential growth, a mechanism that underlies the pandemic and which the lay public understands with difficulty [55,56]. The transmission process should be clearly explained to the public, for instance, in the form of a mental model [57], such as the model suggested by Michie et al6. The use of affective information may be useful: fear is a negative emotion that can have a functional role in the reduction of risky behavior [58,59]. Under this view, maintaining a certain level of fear through risk communication may help to maintain vivid fear mental imagery and, thus, help people to remain cautious in their behavior. Finally, besides addressing tailored messages to specific communities (younger population, little educated people, etc.), communication should be addressed through the right channels to the right population. Indeed, more than 3.8 billion people use social media around the world [60] and they are likely to rely on these media to get informed on the pandemic, not on traditional media (television, radio,

newspapers). Authorities and experts should, thus, make sure that their messages reach everybody in the right form and through the right channel.

3.3. Confidence and Trust

Regarding confidence and trust, the objective of risk communication would be to induce confidence and/or create trust in order to lead recalcitrant people—i.e. those who can comply with protective measures but do not, due to lack of confidence or trust—to adopt protective behaviors.

Firstly, it is important to know whether the noncompliance is truly due to a lack of confidence or trust. But this is difficult: the role of trust is often investigated through questionnaires and surveys, with analysis of correlation relationships (for instance, between perceived trust and reported compliance with protective measures), and not through causal relationships. Yet it is possible that there is no causal effect: for instance, the study carried

6 https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/03/11/slowing-down-the-covid-19-outbreak-changing-behaviour-by-understanding-it/

out by Druckman et al. [61] showed that the respondents expressed affective polarization that leads to an unconditional support to the political party to which they feel to belong to (or an unconditional hostility towards the party they do not like). In such a case, and in other cases where people choose what to fear [34], attitude and behavior are related to uncritical approval (or rejection) that does not rely on particular expectations in terms of confidence and trust. This absence of particular expectations may be applied to the global decrease of public trust observed by Breakwell since the 90’s with the arrival of new channels of communication which have increased societal uncertainty [62]. Anyway, this general skepticism may be something more complex than trust and, above all, it is multidimensional [63]. Eventually, noncompliance to protective measures may be the expression of hostility to any form of authority, which excludes the question of the role of both confidence and trust in risk judgment and risk decision (the problem is that this rejection of authority drives to attitude and behavior that ignore others).

Therefore, if communication aims at improving confidence and trust, it is important to distinguish the object of confidence and trust, especially if different objects of trust and distrust coexist as it is noticed in [63], each of them having its own dimensions.

Communicating towards people who are not confident in government in general, and

communicating towards people who do not trust a vaccine manufacturer in particular, cannot be the same. It is, thus, very important to identify people’s expectations for each object of confidence and trust in order to address specifically these expectations in the messages. Such investigation is difficult regarding confidence because, as a feeling, it is produced by human mind’s experiential System 1, that is without effort and rather unconsciously [18]. An attempt to analyze the causes of confidence will necessarily require a posteriori rationalization, which will bias the results.

We consider here two COVID-19-related trust issues, namely, trust in political institutions and trust in vaccines, in order to make clear the need to identify the object of trust and related expectations, and their consequences on communication and education.

3.3.1. Trust in Political Institutions

The international survey related by Han et al. carried out with 23 countries during April and March 20207 showed that the determinants of trust in government associated to health and pro-social behavior during the pandemic were: government’s organization in response to the

pandemic; transparency and effective communication (i.e. clear information and knowledge about the number of infected cases, the capacity of the health system, and unambiguous health instructions); and fairness (i.e. equal treatment for all people in the society). A study carried out in Australia and New Zealand with data collected in July 2020 [64] shows that trust in government had increased during the pandemic, and this increase was associated with positive perceptions of the government management of the pandemic. These two studies show that expectations towards political institutions seem to be: responsiveness to the pandemic management, information and knowledge, and fairness for all citizens.

Communication should, thus, emphasizes on: government efforts, the progress of knowledge of the disease and pandemic, the known and unknown uncertainties8, and the consideration of all population strata, despair of individuals and economic interests. A study carried out with data collected during March and April 2020 in 178 countries [65,66] show that trust in government increases with age and health conditions, and decreases when the level of

education increases. These results confirm that communication should be shaped according to audience socio-demographics and use various channels to reach all people (see Section 3.2). Eventually, trust is mutual, so that the question of trust in the public must also be raised [67]: communication should emphasize the collective efforts, from the government on one side, and from the citizens who are expected to comply with protective measures on the other side.

3.3.2. Trust in COVID-19 Vaccination

The literature shows that trust in COVID-19 vaccination depends on several kinds of trust, among which those mentioned in Section 2.8, i.e. trust in the health system, trust in the vaccine manufacturer, trust in the effectiveness and safety of vaccines, trust in health-care professionals and trust in science. Rutjens et al. pointed out that vaccination skepticism may reflect a lack of trust in science [68]: this shows that confidence in vaccination in general is a different concept from trust in COVID-19 vaccines. In the former, communication may, for instance, focus on the researchers’ efforts and the progress of knowledge on the Coronavirus, the disease and the pandemic; in the latter, it should focus on vaccines, i.e., their effectiveness and safety, the benefits for self and others. The World Health Organization (WHO) points out that communication on vaccines should be “targeted, credible and clear,” and made by trusted sources to ensure trust in health system and favor vaccination uptake; trust in vaccines must be built timely, before people form a negative opinion against them9. The WHO emphasizes

8 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331513

the role of social pressure and interpersonal trust in vaccination decision-making: the mutual influence of people “can spread through a social cascade”; it is thus important to target the central people in a given network (e.g. health professionals) who will have the task to influence vaccination decision-making. People primarily expect safety of COVID-19 vaccines, but trust in vaccines may be influenced by information contradicting the safety of vaccines, such as past reported side effects of other vaccines [69], which reflects confidence rather than trust, involving both the availability and affect heuristics: people do not take the time for analytical reflections (see Section 2.1). Communication should, thus, repeat the positive effects of vaccination, such as long-lasting protection and socio-economic welfare, in order to induce positive feelings towards vaccination and vaccines.

4. CONCLUSION

In this paper, we have detailed the relationships between various kinds of factors—namely, biases and heuristics, affective and social factors—which influence how people see the scene associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. We highlighted that the perceptions of risk and decision-making related to protective behaviors are shaped by people’s mental models of risk—including their individual and shared moral values—and by the confidence and trust in involved parties, such as government, science, the health system, vaccination, etc. This has led us to advocate, with an innovative look, a view of risk education and communication articulated around the resilience of moral values, mental models of risk and trust, for improved social resilience, not only during the pandemic, but also for future disasters. The societal resilience can be considered through another concept that of ethics of resilience, which is implicit in the work of the philosopher Naomi Zack when she recommended

building a code of ethics for disaster [70]. Both resilient ethics and ethics of resilience must be the basis for deployment of the four phases of the integrated approach of risk and

resilience management needed to deal with disasters: prevention/mitigation comprising all activities for reducing the probability of disaster occurrence; protection/preparation related to all safety measures and activities that are designed and planned to enter in action when the disaster occurs, in order to reduce its impact and minimize losses; response as obtained by the activities of emergency and crisis management implemented during the aftermath of the accident to control its impact, prevent additional damage and loss; finally, recovery for restoring back to a normal or improved situation after the disaster [71].

To conclude, an ethic of resilience for disaster management would necessarily have an inclusive view, such as the qualitative model of patterns of resilience and vulnerability described in [72], and the globalization and global risk perspective [73]. Nevertheless, more fundamental and transdisciplinary research is needed to develop an ethic of resilience and achieve the integration of the two faces of ethics in disaster management.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors warmly thank the reviewers for their constructive comments.

Many thanks to Atlantis Press for the authorization to deposit in HAL Archives Ouvertes this revised manuscript submitted to the Journal of Risk Analysis and Crisis Response.

REFERENCES

[1] C. Huang. Analysis of death risk of COVID-19 under incomplete information. J Risk Anal Crisis Response, 2020, Volume 1(2), 43-53. https://dx.doi.org/10.2991/jracr.k.200709.002. [2] G. Gigerenzer, H. Brighton. Homo heuristicus: Why biased minds make better inferences. Top

Cogn Sci, 2009, Volume 1(1), 107-143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2008.01006.x. [3] D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, A. Tversky. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases.

Cambridge University Press, New York, 1982.

[4] P. Slovic, M.L. Finucane, E. Peters, D.G. MacGregor. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Anal, 2004, Volume 24(2), 311-322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x.

[5] N.D. Weinstein. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J Pers Soc Psychol, 1980, Volume 39(5), 806-820. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.806.

[6] G.M. Breakwell. The psychology of risk, 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2014.

[7] A. Rosi, F.T. van Vugt, S. Lecce, I. Ceccao, M. Vallarino, F. Rapisarda et al. Risk perception in a real world (COVID-19): How it changes from 18 to 87 years old. Front Psychol, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646558.

[8] N. Villain. Ultracrepidarianism, cognitive biases, and COVID-19. Rev Neuropsychol, 2020, Volume 12(2), 216-217. https://www.jle.com/10.1684/nrp.2020.0549.

[9] M. LaCour, T. Davis. Vaccine skepticism reflects basic cognitive differences in mortality-related event frequency estimation, 2020, Volume 38(21), 3790-3799.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.02.052.

[10] E. Guastaffiero, C. Toppo, F.G. Magnani, R. Romano, C. Facchini, R. Campioni. Older adults’ risk perception during the pandemic in Lombardy Region of Italy: A cross-sectional survey. J Gerontol Soc Work, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2020.1870606.

[11] J.M. Garcia-Alamino. Human biases and the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Intensive Crit Care Nurs, 2020, Volume 58, 102861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102861.

[12] A.A. Madison, B.M. Way, T.P. Beauchaine, J.K. Kiecolt-Glaser. Risk Assessment and heuristics: How cognitive shortcuts can fuel the spread of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.02.023.

[13] E. Druica, F. Musso, R. Ianole-Călin. Optimism bias during the Covid-19 pandemic: Empirical evidence from Romania and Italy. Games, 2020, Volume 11(3), 39.

https://doi.org/10.3390/g11030039.

[14] D. Dolinski, B. Dolinska, B. Zmaczynska-Witek, M. Banach, W. Kulesza. Unrealistic optimism in the time of coronavirus pandemic: May it help to kill, if so—Whom: Disease or the person? J Clin Med, 2020, Volume 9(5), 1464. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051464. [15] N.D. Weinstein, J.E. Lyon. Mindset, optimistic bias about personal risk and health-protective

behaviour. Br J Health Psychol, 1999, Volume 4(4), 289-300. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910799168641.

[16] P. Slovic, M.L. Finucane, E. Peters, D.G. MacGregor. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Anal, 2004, Volume 24(2), 311-322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x.

[17] R.B. Zajonc. Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. Am Psychol, 1980, Volume 35(2), 151-175. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.35.2.151.

[18] D. Kahneman. Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2011. [19] M. Vacondio, G. Priolo, S. Dickert, N. Bonini. Worry, perceived threat and media

communication as predictors of self-protective behaviors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Europe. Front Psychol, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.577992.

[20] K. Nakayachi, T. Ozaki, Y. Shibata, R. Yokoi. Why do Japanese people use masks against COVID-19, even though asks are unlikely to offer protection from infection? Front Psychol, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01918.

[21] J.M. Barrios, Y. Hochberg. Risk perception through the lens of politics in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Working paper No. w27008, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2020. Available at: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/bfiwpaper/2020-32.htm (accessed 6 March 2021).

[22] X. Xiang, X. Lu, A. Halavanau, J. Xue, Y. Sun, P.H.L. Lai, Z. Wu. Modern senicide in the face of a pandemic: An examination of public discourse and sentiment about older adults and COVID-19 using machine learning. J Gerontol, Series B: Psychol Soc Sci, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa128.

[23] K.K. Cheng, T.H. Lam, C.C. Leung. Wearing face masks in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic: Altruism and solidarity. The Lancet, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30918-1.

[24] D.R. Forsyth. Group-level resistance to health mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic: A groupthink approach. Group Dyn-Theor Res, 2020, Volume 24(3), 139-152.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/gdn0000132.

[25] T.L.D. Huynh. Does culture matter social distancing under the COVID-19 pandemic? Saf Sci, 2020, Volume 130, 104872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104872.

[26] A.L. Whitehead, S.L Perry. How culture wars delay herd immunity: Christian nationalism and anti-vaccine attitudes. Socius: Sociol Res Dyna World, 2020, Volume 6, 1-12.

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2378023120977727.

[27] J.N. Dinga, L.K. Sinda, V.P.K. Titanji. Assessment of vaccine hesitancy to a COVID-19 vaccine in Cameroonian adults and its global implication. Vaccines, 2021, Volume 9(2), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020175.

[28] K. Schmelz. Enforcement may crowd out voluntary support for COVID-19 policies, especially where trust in government is weak and in a liberal society. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A., 2021, 118(1), e2016385118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2016385118.

[29] S. Altmann, L. Milsom, H. Zillesen, R. Blasone, F. Gerdon, R. Bach et al. Acceptability of app-based contact tracing for COVID-19: Cross-country survey study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 2020, Volume 8(8), e19857. https://doi.org/10.2196/19857.

[30] M. Al-Mohaithef, B.K. Padhi. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine in Saudi Arabia: A Web-based national survey. J Multidiscip Healthc, 2020, Volume 13, 1657-1163.

https://dx.doi.org/10.2147%2FJMDH.S276771.

[31] P. Verger, E. Dubé. Restoring confidence in vaccines in the COVID-19 era. Expert Rev. Vaccines, 2020, Volume 19(11), 991-993. https://doi.org/10.1080/14760584.2020.1825945. [32] M. Schwarzinger, V. Watson, P. Arwidson, F. Alla; S. Luchini. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy

in a representative working-age population in France: A survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health, 2021, Volume 6(4), e210-e211.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8.

[33] L.C. Karlsson et al. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: The case of COVID-19. Pers Indiv Differ, 2021, Volume 172, 110590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110590.

[34] A. Wildavsky, K. Dake. Theories of risk perception: Who fears what and why? Daedalus, 1990, Volume 119(4), 41-60.

[35] M. Hunyadi. Au début était la confiance [At the beginning was trust]. Éditions Le Bord de l’Eau, Lormont, France, 2020.

[36] B. Fischhoff. Risk perception and communication unplugged. Twenty years of process. Risk Anal, 1995, Volume 15(2), 137-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb00308.x. [37] O.A. Atabuga, J.E. Atabuga. Social determinants of health: The role of effective

communication in the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Global Health Action, 2020, Volume 13(1), 1788263. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2020.1788263.

[38] R. Chatterjee, S. Bajwa, D. Dwivedi, R. Kanji, M. Ahammed, R. Shaw. COVID-19 risk assessment tool: Dual application of risk communication and risk governance. Progress Disaster Sci, 2020, Volume 7, 100109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100109. [39] L. Zhang, H. Li, K. Chen. Effective risk communication for public health emergency:

Reflection on the COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) outbreak in Wuhan, China. Healthcare, 2020, Volume 8(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010064.

[40] C. Castelfranchi, R. Falcone. Trust is much more than subjective probability: Mental components and sources of trust. Proc. 33rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Maui, HI, USA, 7 Jan. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2000.926815. [41] A.H. Kwok, E.E. Doyle, J. Becker, D. Johnston, D. Paton. What is ‘social resilience’?

Perspectives of disaster researchers, emergency management practitioners, and policymakers in New Zealand. Int J Disas Risk Reduction, 2016, Volume 19, 197-211.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.08.013.

[42] J. Mizzoni. Ethics: The basics, 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, United Kingdom, 2017.

[43] M.L. Finucane. Improving quarantine risk communication: Understanding public risk

perceptions. Decision Research Faculty Work (Report No. 00-7), University of Oregon (OR), 2000. Available at: https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/20645 (accessed 4 April 2021).

[44] G. Alessandri, L. Filosa, M.S. Tisak, E. Crocetti, G. Crea, L. Avanzi. Moral disengagement and generalized social trust as mediators and moderators of rule-respecting behaviors during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychol, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02102.

[45] E.M. Abrams, M. Greenhawt. Risk communication during COVID-19. J Allerg Clin Immunol Pract, 2020, Volume 8(6), 1791-1794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.012.

[46] B. Fischhoff. The importance of testing messages. Bull World Health Organization, 2020, Volume 98, 516-517. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.030820.

[47] L. Yang, Y. Ren. Moral obligation, public leadership, and collective action for epidemic prevention and control: Evidence from the corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emergency. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020, Volume 17(8), 2731.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082731.

[48] S. Dryhurst, C.R. Schneider, J. Kerr, A.L.J. Freeman, G. Recchia, A.M. van Der Bles. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J Risk Res, 2020, Volume 23(7-8), 94-1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193.

[49] J.J. Van Bavel, K. Baicker, P.S. Boggio, V. Capraro, A. Cichocka, M. Cikara et al. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav, 2020, Volume 4, 460-471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z.

[50] M. Siegrist, L. Luchsinger, A. Bearth. The impact of trust and risk perception on the acceptance of measures to reduce COVID-19 cases. Risk Anal, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13675. [51] P.D. Lunn, C.A., Belton, C. Lavin, F.P. McGowan, S. Timmons, D. Robertson. Using

behavioral science to help fight the Coronavirus: A rapid, narrative review. J Behav Public Adm, 2020, Volume 3(1). https://doi.org/10.30636/jbpa.31.147.

[52] H. Jonas. Technology and responsibility: Reflections on the new tasks of ethics. Soc Res, 1973, Volume 40(1), 31-54.

[53] P. Slovic. The perception of risk. Earthscan, New York, 2000.

[54] V. Thoma, L. Weis-Cohen, P. Filkulková, P. Ayton. Cognitive predictors of precautionary behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol, 2021, Volume 12, 589800. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.589800.

[55] R. Banerjee, J. Bhattacharya, P. Majumdar. Exponential-growth prediction bias and compliance with safety measures related to COVID-19. Soc Sci Med, 2021, Volume 268, 113473.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113473.

[56] H. Kunreuther, P. Slovic. Learning from the COVID-19 pandemic to address climate change. Management and Business Review, 2021. Available at:

https://mbrjournal.com/2021/01/26/learning-from-the-covid-19-pandemic-to-address-climate-change/ (accessed 4 April 2021).

[57] S. Van den Broucke. Why health promotion matters to the COVID-19 pandemic, and vice versa. Health Promot Int, 2020, Volume 35(2), 181-186.

https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa042.

[58] L. Cori, F. Bianchi, E. Cadum, C. Anthonj. Risk Perception and COVID-19. Int J Env Res Public Health, 2020, Volume 17(9), 3114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093114. [59] C.A. Harper, L.P. Satchell, D. Fido, R.D. Latzman. Functional fear predicts public health

compliance in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Addiction, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00281-5.

[60] C. Cuello-Garcia, G. Pérez-Gaxiola, L. van Amelsvoort. Social media can have an impact on how we manage and investigate the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Epidemiol, 2020, Volume 127, 198-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.028.

[61] J.N. Druckman, S. Klar, Y. Krupnikov, M. Levendusky, J.B. Ryan. Affective polarization, local contexts, and public opinion in America. Nat Hum Behav, 2021, Volume 5, 28-38.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01012-5.

[62] G.M. Breakwell. Mistrust, uncertainty and health risks. Contemp Soc Sci, 2020, Volume 15(5), 504-516. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2020.1804070.

[63] L. Fjaeran, T. Aven. Creating conditions for critical trust – How an uncertainty-based risk perspective relates to dimensions and types of trust. Saf Sci, 2021, Volume 133, 105008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.105008.

[64] S. Goldfinch, R. Taplin, R. Gauld. Trust in government increased during the Covid-19 pandemic in Australia and New Zealand. Aust J Public Adm, Volume 80(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12459.

[65] T.R. Fetzer, M. Witte, L. Hensel, J. Jachimowicz, J. Haushofer, A. Ivchenko et al. Global Behaviors and Perceptions at the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Working Paper 27082. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge (MA), 2020. DOI: 10.3386/w27082. [66] G. Gozgor. Global evidence on the determinants of public trust in governments during the

COVID-19. Appl Res Qual Life, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09902-6. [67] C.M.L. Wong, O. Jensen. The paradox of trust: perceived risk and public compliance during

the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore. J Risk Res, 2020, Volume 23(7-8), 1021-1030. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1756386.

[68] B.T. Rutjens, S. van der Linden, R. van der Lee. Science skepticism in times of COVID-19. Group Process Intergroup Relat, 2021, Volume 24(2), 276-283.

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1368430220981415.

[69] A. Borriello, D. Master, A. Pellegrini, J.M. Rose. Preferences for a COVID-19 vaccine in Australia. Vaccine, 2021, Volume 39(3), 473-479.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.032.

[70] N. Zack. Ethics for disasters. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., Lanham (MD), 2010. [71] E. Zio. Challenges in the vulnerability and risk analysis of critical infrastructures. Reliab Eng

Syst Saf, 2016, Volume 152, 137-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2016.02.009.

[72] T. Kontogiannis. A qualitative model of patterns of resilience and vulnerability in responding to a pandemic outbreak with system dynamics. Safety Sci, 2021, Volume 134, 105077.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.105077.

[73] T. Aven, E. Zio. Globalization and global risk: How risk analysis needs to be enhanced to be effective in confronting current threats. Reliab Eng Syst Saf, 2021, Volume 205, 107270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2020.107270.