ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Mammalian

Biology

j o ur na l ho me p ag e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / m a m b i o

Original

investigation

Comparison

of

diet

and

prey

selectivity

of

the

Pyrenean

desman

and

the

Eurasian

water

shrew

using

next-generation

sequencing

methods

Marjorie

Biffi

a,∗,

Pascal

Laffaille

a,

Jérémy

Jabiol

a,

Adrien

André

b,

Franc¸

ois

Gillet

b,

Sylvain

Lamothe

a,

Johan

R.

Michaux

b,c,

Laëtitia

Buisson

aaEcoLab,UniversitédeToulouse,CNRS,INPT,UPS,118routedeNarbonne,31062Toulousecedex9,France

bLaboratoiredeBiologieEvolutive,UnitédeGénétiquedelaConservation,UniversitédeLiège,InstitutdeBotaniqueB22,QuartierVallée1,Chemindela

Vallée4,4000Liège,Belgium

cCIRAD,AgirsUnit,TAC-22/E-CampusinternationaldeBaillarguet,34398MontpellierCedex5,France

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received9December2016 Accepted12September2017 HandledbyLauraIacolina Availableonline14September2017 Keywords: COI Dietaryoverlap Foragingstrategy Scatanalyses Semi-aquaticmammal

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Inthisstudy,theinteractionsbetweentwosemi-aquaticmammals,theendangeredPyreneandesman GalemyspyrenaicusandtheEurasianwatershrewNeomysfodiens,wereinvestigatedthroughtheanalysis oftheirsummerdietusingnext-generationsequencingmethods,combinedwithanalysesofprey selec-tivityandtrophicoverlap.Thedietofthesepredatorswashighlydiverseincluding194and205genera forG.pyrenaicusandN.fodiensrespectively.Overall,bothspeciesexhibitedrathernon-selectiveforaging strategiesasthemostfrequentlyconsumedinvertebrateswerealsothemostfrequentandabundantin thestreams.ThissupportedageneralistforagingbehaviourforG.pyrenaicusandN.fodiensinthestudy area.ThePiankaindex(0.4)indicatedasignificantbutmoderatedietaryoverlapasG.pyrenaicusmostly reliedonpreywithaquaticstageswhereaspreyofN.fodiensweremainlyterrestrial.Moreover,no dif-ferenceinG.pyrenaicuspreyconsumptionwasfoundinpresenceorabsenceofN.fodiens.Adifferential useoftrophicresourcesthroughmechanismssuchasplasticfeedingbehaviourordifferencesinforaging micro-habitatarelikelytofacilitatethecoexistencebetweenthesetwomammalspecies.

©2017DeutscheGesellschaftf ¨urS ¨augetierkunde.PublishedbyElsevierGmbH.Allrightsreserved.

Introduction

Biodiversityconservationrequiresathoroughknowledgeofthe

complexnatureofinteractions betweenspeciesand their

envi-ronment.Accordingtotheecologicalnichetheory(Hutchinson,

1957),sympatricspeciesareexpectedtoexhibitsomeniche

dif-ferentiationinpreyorhabitatusetocoexist(Pianka,1974).Under

limitingconditions,strongnicheoverlapbetweenspeciesmaylead

tostrongcompetitiveinteractions,andmayultimatelyresultinthe

competitiveexclusionoftheweakestcompetitorimplying

conse-quencesonitslocalandregionaldistribution(Wiszetal.,2013).The

studyofresourceuseandpotentialnicheoverlapwith

competi-torsseemsthuscrucialtoassessthevulnerabilityofspecieswith

Abbreviations:FOdiet,frequencyofoccurrenceofinvertebratetaxainthe

preda-tordiet(numberoffaecescontainingthetaxondividedbythetotalnumberof predatorfaeces); FOstream,frequencyofoccurrenceofinvertebratetaxainthe

streams(numberofSurbersampleswiththetaxadividedbythetotalnumberof Surbersamplescollectedinthestudysites).

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:m.biffi@live.fr(M.Biffi).

conservationconcern.Thisisparticularlytruewhenfocusingon

specieslivinginecosystemsthatarevulnerabletoanthropogenic

alterations,suchasfreshwaterecosystems(Dudgeonetal.,2006).

Anyquantitativeor qualitativeshiftin theresource availability

and/ordiversity(e.g.preycommunity)followingdisturbance(e.g.

aquaticpollution,alterationofriverflow)mayexacerbatethe

com-petitiveinteractionsbetweenconsumers.

ThePyreneandesman,Galemyspyrenaicus(E.Geoffroy

Saint-Hilaire,1811,Talpidae)isasmallsemi-aquaticmammal,endemic

tothePyreneesMountainsandtheIberian Peninsula(northern

and central Spain, northern Portugal). The species is listed as

vulnerable by the IUCN (Fernandes et al., 2008)and is legally

protectedinallthecountriesencompassingitsdistributionarea.

ThealarmingdeclineofG.pyrenaicuspopulationsovertherecent

decadesacrossitswholerange(Charbonneletal.,2016;Gisbert

andGarcía-Perea,2014)hasencouragedlocal,nationaland

Euro-peanconservationinitiatives(e.g.,inFrance:Life+Desman,2013;

Némozetal.,2011).Yet,inspiteofanincreasingnumberof

stud-iesfocusingonthisspecies(e.g.,AymerichandGosàlbez,2015;Biffi

etal.,2016;Charbonneletal.,2016;Escodaetal.,2017),the

respec-tiveinfluenceofprey,competitorsandpredatorsonitssurvivaland

distributionstillremainstobeexplored.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2017.09.001

Modernadvancesinmoleculargeneticswererecentlyapplied

toinvestigate the diet of G. pyrenaicus in the French Pyrenees

(Gillet, 2015; Gilletet al.,2015).Theystressed thewide

diver-sityof prey(156genera) withhalfof them beingfoundinthe

dietofG.pyrenaicusforthefirsttime.Besides,thesefirststudies

confirmedthedietarypreferencesof G.pyrenaicustowards

Tri-choptera,EphemeropteraandPlecoptera(Insecta),aspreviously

knownfromtraditionalmethodsbasedongutcontentanalysisor

visualinspectionoffaecesremains(e.g.,Bertrand1994;Castiénand

Gosálbez1995;Santamarina1993;SantamarinaandGuitian1988).

Inaddition,Gillet(2015)emphasizedasubstantialconsumptionof

terrestrialprey.

Several aquatic or semi-aquatic animals are knownto prey

and use similar food and habitat resources as G. pyrenaicus

and act as potential competitors for resource acquisition: the

browntroutSalmotruttaandthedipperCincluscinclus(Bertrand,

1994; Santamarina, 1993; Santamarina and Guitian, 1988), the

EurasianwatershrewNeomysfodiens(CastiénandGosálbez1999;

Morueta-Holmeetal.,2010;SantamarinaandGuitian1988),the

MediterraneanwatershrewNeomysanomalus(Santamarina,1993)

and thePyreneanbrook newt Calotritonasper(Bertrand, 1994).

AmongthesespeciesN.fodiensexhibitssimilarhabitatpreferences

asG.pyrenaicus,i.e.swiftly-flowingstreamswithnumerous

shel-ters(e.g.cavities)ontheriverbeds(Greenwoodetal.,2002;Keckel

etal.,2014).N.fodiensisalsoknownasanopportunisticfeeder

consumingbothaquatic(e.g.,crustaceans,insectlarvae)and

ter-restrial(e.g,coleopterans,gastropods,spiders,earthworms)prey

(CastiénandGosálbez,1999;Churchfield,1985;Churchfieldand Rychlik,2006;Haberl,2002).Moreover,N.fodiensexhibitsa

simi-larpolyphasicactivitypatternasG.pyrenaicus(Meleroetal.,2014),

withactivityphases varyingacross seasons(Churchfield, 1984;

Greenwoodetal.,2002;Keckeletal.,2014;Rychlik,2000).Despite

importantsimilaritiesintheirhabitat,resourcepreferencesandlife

style,fewstudieshavefocusedonthetrophicoverlapbetweenN.

fodiensandG.pyrenaicustodate.Thesestudies,limitedtosmall

samplessizes(e.g.,onlysixG.pyrenaicussamplesinSantamarina,

1993)andrelyingsolelyonthevisualinspectionofpreyremainsin

faecesorgutcontent,concludedthatcoexistenceanddiet

differ-entiationwerelikelytheresultofadifferentuseofmicro-habitats

(CastiénandGosálbez,1999).

Duringthepastyears,moleculargeneticmethodsbasedon

fae-cesanalyseswereincreasinglyusedinsteadof‘traditional’methods

basedongutcontentanalysisorvisualinspectionoffaecesremains

(Pompanonetal.,2012).Theirmainadvantagesarethat(i)they

donot requestanimal sacrificecomparedtogutcontent

analy-sis,(ii)theyidentifypreywithhightaxonomicresolution(genus

andspecieslevels),(iii)includinghighlydegradedorsoft-bodied

species(molluscs,earthworms)thatcannotbeidentified

morpho-logically,(iv)theyarelesstime consuming,and (v)theydonot

requireanytaxonomicalexpertiseoftherangeofpotentialpreyas

longastaxaarepresentingeneticdatabases(seePompanonetal.,

2012forareview).Todate,thoughthedietofG.pyrenaicushasbeen

recentlydescribed usingmolecularmethods(Gillet,2015;Gillet

etal.,2015;Biffietal.,2017),suchdataaboutN.fodienshavenever

beengathered,makinganycomparisonoftherespectivedietsof

thesetwospeciesratherspeculative.

Inthisstudy,weaimedatdescribingthesummerdietofthese

twomammals,usingrecentmoleculargeneticmethods,inapart

oftheFrenchPyrenees(i.e.,theAriègedepartment)where they

areknowntoco-occur.Moreover,wecomparedthepreyofthese

predatorspecieswithstreambenthicinvertebratecommunities,on

whichG.pyrenaicusmostlyfeeds.Thisallowedusassessingtheprey

selectivityofthesetwomammalspeciesandthepotentialtrophic

overlapduringsummerinordertodiscussmechanismsthatcould

facilitatetheircoexistence.

Materialandmethods

Studyareaandsamplingsites

Samplingwas conducted in 65 sites spread over the Ariège

department,aFrenchadministrativeregioninthePyrenees

Moun-tains(Fig.1).ThisareaexhibitsrelativelyhighoccurrenceofG.

pyrenaicus(Biffietal.,2016;Charbonneletal.,2015,2016),and

the presence of N. fodiens was recently reported (Charbonnel

et al., 2015). The mean elevation of the 65 sampling sites is

757.9±259.3mandvariesbetween375.2mand1755.6m.Mean

monthly streamflow equals to1.1±2.0m3/s witha maximum

of13.2m3/s(Charbonneletal.,2016).Naturalzoneswith

herba-ceous or shrubby vegetation (52.1±36.1%), agricultural lands

(43.9±34.7%)andforests(40.6±32.5%;CorineLandCover©DB

2012)dominatethelandcover surroundingthe65sites.Inthis

mountainous area, the climate is cold (mean annual air

tem-perature=10.4±1.3◦C, SAFRAN © DB) and wet (mean annual

rainfall=1141.0±110.9mm,SAFRAN©DB).

Faecessamplingandmoleculargeneticsanalyses

FaecescollectionofG.pyrenaicusandN.fodienswereconducted

twicebetweenJuneandSeptember2015inthe65selectedsites

(Fig.1).Skilledobserversmeticulouslyinspectedeachemergent

item(i.e.,rock,treerootorbranch)alonga250mriverbed

tran-sect.Thislengthisacompromisebetweenthehomerange(HR)size

andtheaveragedistancetravelledalongstreamchannels(ADTS)

during24hforN.fodiens(narrowandlinearHRalongastream:

106–509m2,ADTS:49±25m;Cantoni,1993;Lardet, 1988)and

G. pyrenaicus (linear HR: ≈500m; ADTSbetween resting sites:

≈250m;Meleroetal.,2012,2014).Oursamplingprotocolmeets

therecommendationsofParryetal.(2013)whofoundthat

repeat-ingvisitsinasinglesiteratherthanenlargingthesampledarea

allowedbetterdetectionprobabilitiesfortheEurasianotter.Itis

alsoinagreementwithCharbonneletal.(2014)whoobtained

rea-sonabledetectionprobabilitiesforG.pyrenaicus(0.58)inasurvey

of 100m-longsectionsof riversusingtemporal replicates.The

searchforfaecesisastandardandeffectiveprotocolfor

detect-ingthepresenceofG.pyrenaicus(Charbonneletal.,2014)andhas

alsoprovenefficiencyforN.fodiens(AymerichandGosálbez,2004).

AllputativeG.pyrenaicusorN.fodiensfaeces basedontheir

colour,size,smellandposition,werecollectedandanalysedwith

moleculargenetictoolsbothtoconfirmthespeciesidentityofthe

consumerandthepreyconsumed.Followingthemanufacturer’s

instructions, DNA wasextracted from faecal samplesusing the

StoolMiniKit(Qiagen Inc.,Hilden,Germany).PCRamplification

wasduplicated for each sample ona portionof the

mitochon-drialcytochromeoxydaseIgene(COI;fordetails,seeGilletetal.,

2015).NegativeDNAextractionandnegativePCRcontrolswere

includedintheprocedure.AgencourtAMPureXPbeads(Beckman

CoulterLifeSciences,IN,USA)and thenQuant-iTTM PicoGreen®

dsDNAAssayKit(ThermoScientific,MA,USA)wereusedto

puri-fiedPCRproductsandtoquantifiedpurifiedampliconsrespectively.

Afterthequantificationstep,productswerepooledat

equimolar-ityandsenttotheGIGAGenomicsplatform(UniversityofLiège,

Belgium) for sequencing on an ILLUMINA MiSeq V2 benchtop

sequencer.Rawsequencesweresortedandfilteredusingascript

mixingFASTXToolkit(http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastxtoolkit;

23-09-16) and USEARCH (Edgar,2010)functions (seeAndré etal.,

2017fordetailsonbioinformatics).Sequencesoriginatinglikely

fromextractionorPCRcontaminantswereexcludedfromfurther

analyses.Theremainingsequenceswerethencomparedwith

pub-lished sequencesavailable intheonline BOLDdatabaseforCOI

(Ratnasinghamand Hebert,2007).Sequencesthat hadaunique

Fig.1. Locationofthestudyareaandsamplingsites(blackdots)inFrance.

score(i)higherorequalto90%fortheidentificationofpreytaxaat

thegenuslevel(whenpossible),and(ii)higherorequalto99%for

theidentificationofthepredatoratthespecieslevel.

PreytaxawerevalidatedaspotentiallyoccurringinFranceand

inthePyreneesusing theFrenchNationalInventoryof Natural

Heritage(Muséumnationald’Histoirenaturelle,2003–2017)and

theFrenchOfficeforInsectsandtheirEnvironment(OPIE-Benthos,

2017)onlinedatabases.Taxaidentifiedasendemicofotherpartsof

theworldwerekeptintheanalysisanddesignatedbyanasterisk

hereafter(*)astheymorelikelycorrespondtoageneticallysimilar

taxonpresentinthePyreneesbutabsentinthegeneticdatabases.

Whenpreytaxacouldnotbeidentifiedatthegenuslevel,theywere

groupedtogetheratahighertaxonomiclevel.

Aquaticmacroinvertebratessampling

Aquaticmacroinvertebrateswerecollectedin27outofthe65

sites,amongwhich N.fodiensandG.pyrenaicuswerepresentin

19and25sites,respectively(called“Neomyssites”and“Galemys

sites”,respectively).G.pyrenaicuswasdetectedaloneineightsites

(“Galemysalonesites”)andbothspecieswerefoundtoco-occurin

17sites(“Galemys+Neomyssites”).N.fodienswasdetectedalonein

twosites(“Neomysalonesites”).

The available habitats for aquatic macroinvertebrates were

describedaccordingto12categoriesofsubstratetype:bryophytes,

hydrophytes, helophytes, litter, twigs roots, algae,large stones

(>25cm),cobbles/pebbles(2.5–25cm),gravel(0.2–2.5cm),mud,

sand,bedrock;andfourcategoriesofcurrentvelocity:null,slow,

medium,fast.Thepercentagecoverofeachcombinationof

sub-stratetype/currentvelocitywasvisuallyestimatedineachsite.

Six Surber net samples (mesh size: 500m, sampled area:

0.04m2)wereconductedineachsiteaccordingtoastratified

sam-plinginthedominanthabitats(e.g.mainlycoarsemineralsubstrate

inhigh-flowfacies)coveringmorethan5%ofeachstreamtransect

inordertoberepresentativeofthesite.Thesampled

macroinver-tebrateswerefrozenbeforebeingsorted,countedandidentifiedat

thefamilylevel(exceptforOligochaetaandHydracarina)following

Tachetetal.(2000)atthelaboratory.Themeandensity(numberof

individuals/m2),andthefrequencyofoccurrence(FO

stream:relative

numberofSurbersampleswiththetaxon)werethencalculatedfor

eachsiteandinvertebratetaxon.

Mean macroinvertebrates densities were compared with

Wilcoxonsign-rankedtestsandP-valuesadjustedwiththe

Bon-ferronicorrection,betweencategoriesofsites(i.e.,Galemysalone

sites,NeomysalonesitesandGalemys+Neomyssites).

Dietcompositionandcomparisonbetweenmammals

Presenceor absenceof prey in each faeces of G. pyrenaicus

andN.fodienswereusedtodescribethedietcompositionofboth

species.Thefrequencyofoccurrence(FOdiet,i.e.,thenumberof

fae-cescontainingthetaxondividedbythetotalnumberoffaeces)inG.

pyrenaicusandN.fodiensdietwascalculatedforeachorder,family

andgenusofinvertebratesandforthedifferenttypesofprey’s

habi-tat(i.e.,exclusivelyaquatic,exclusivelyterrestrialorwithaquatic

andterrestrialstages).Tocomparethefaecescompositionbetween

thetwo species,aCorrespondenceAnalysis(CA)wasappliedto

presence-absencedataofpreyinfaecesatthegenuslevel.The

coor-dinatesofeachfaecesonthefirstandsecondaxesoftheCAwere

comparedbetweenthetwospecieswithaStudenttestfor

homo-geneousvariances.Rarepreytaxa,withFOdietbelow5%bothinG.

pyrenaicusandN.fodiensfaeces,werenotincludedinthisanalysis.

ToassesspreyselectivityofG.pyrenaicusandN.fodiens,the

pres-enceofinvertebratesinthefaeceswereconsideredatthesitescale.

Whenaninvertebratetaxonwaspresentinatleastonefaecesof

themammalspeciesinasite,itwasconsideredasbelongingto

themammaldietinthissite.PreyFOdietinthefaeceswerethen

calculatedforthe19Neomyssitesandthe25Galemyssites.Data

onpreyavailabilityinthestreams(i.e.,FOstreampersitefromthe

Surbersamples)andpreyconsumedbythepredatorinthesite

(i.e.,FOdietpersiteinthesampledfaeces)atthefamilylevelwere

comparedusingtheIvlev’selectivityindex(Ivlev,1961).Thisindex

rangesfrom−1(i.e.,avoidanceofprey)indicatingthatthetaxon

isfrequentinstreamsbutneverfoundinfaeces,to1(i.e.,active

selection)whenthetaxonisrareinstreamsbutfoundinavery

highnumberoffaeces.Azerovalueindicatesthatconsumptionis

proportionaltotheamountofinvertebratesavailableinstreams.

5%inboththeSurbersamples(FOstream)andthefaecesofG.

pyre-naicusandN.fodiens(FOdiet)werenotconsideredinthisanalysis.

Trophicoverlapbetweenmammals

TodeterminethedegreeoftrophicoverlapbetweenG.

pyre-naicusandN.fodiensduringsummer,thePianka’sdietaryniche

overlapindex(Pianka,1973)wascalculatedfromthepreyFOdietin

thefaecesatthegenusandfamilylevels.Thisindexrangesfrom0

(notrophicresourceusedincommon)to1(fulldietaryoverlap).

Moreover,totestiftheco-occurrenceofbothmammalspecies

inasitecouldmodifythedietofG.pyrenaicus,thefaeces

composi-tioninpreywascomparedbetweentheGalemysalonesites(8)and

theGalemys+Neomyssites(17).Themeanfrequencyofoccurrence

ofeachpreytaxonfoundinthefaecesofG.pyrenaicus(atthefamily

level)werecomparedwithaWilcoxonsign-rankedtestbetween

thetwocategoriesofsites.ThedietofN.fodienscouldnotbe

com-paredbetweenNeomysalonesitesandGalemys+Neomyssitesdue

toaverysmallnumberofNeomysalonesites(2).

AllstatisticalanalyseswereconductedinR3.3.1(RCoreTeam,

2014)usingtheade4andspaapackages.

Results

Molecularidentificationofpredatorsproducingthefaecesand

preycontents

Atotalof464faeceswerecollectedfromthe65sampledsites

(7±2faecespersite)andanalysedusingmoleculargeneticstools.

AfterthetwoPCRamplifications,atotalof2,160,447readswere

obtained.1,348,331readswerecorrectlyassignedto199faeces

(42.9%)thatbelongedtoG.pyrenaicus(3±2faecespersite)and

whosepresencewasconfirmedin58sites.Amongthem,itwas

possibletoidentifypreyin184faeces.Seventy-ninefaeces(17%

offaeces–463,706reads),including78faeceswithdiet

informa-tion,belongedtoN.fodiens(2±1faecespersite)whichconfirmed

itspresencein39sites.Fromtheremainingfaeces,51(11.0%)were

assignedto14otherhostspecies(mammalssuchasNeomys

anoma-lus,Apodemussp.,Sorexsp.;batsorbirds).Molecularidentification

ofpredatorsandpreyfailedfor29.1%ofthesamplesdueto

insuf-ficientDNAquantityordegradedsamples.

Overalldiversityofpreyinthepredatorfaeces

ThefaecesofG.pyrenaicusandN.fodienscontainedalmost

exclu-sivelyinvertebrate preyexcept oneamphibian foundinone G.

pyrenaicusfaeces.Preydiversitywashighwith10and9classes,

30and33orders(Table1),111and117families,and194and205

genera(AppendixAintheSupplementarymaterial)forG.

pyre-naicusandN.fodiens,respectively.Intotal,309differentgenera

wereidentifiedwhose178wereconfirmedtooccurinthe

Pyre-nees,95inFranceand9wereendemicofotherpartsoftheworld

(e.g.,Australia,America,Asia).Theremaining27taxacouldnotbe

identifiedatthegenuslevelinthedatabasesandtheirdistribution

rangeisunknown.

Forthetwomammalspecies,frequentlyconsumedprey(i.e.,

presentinmorethan5%ofthefaeces)representedasmall

propor-tionofthetotalpoolofpreyconsumed(12.9%and20.5%ofgenera

eatenbyG.pyrenaicusandN.fodiens,respectively).Thedominant

preyfoundinthefaecesofG.pyrenaicuswereInsecta(93.5%of

thefaeces),Malacostraca(23.4%)andDiplopoda(21.7%).Among

insects,G.pyrenaicuspreyedmorefrequentlyonEphemeroptera

(71.2%)whichincludedthemostfrequentfamily(Heptageniidae:

61.4%)butnotthemostfrequentgeneraHydropsyche(Insecta

Tri-choptera Hydropsychidae: 52.7%). N. fodiens seemed to have a

morediversedietwithDiplopoda(89.7%offaeces),Insecta(83.3%),

Arachnida(47.4%),Gastropoda(25.6%) andMalacostraca(24.3%)

occurringfrequentlyinthecollectedfaeces.Thepreyfoundthe

mostfrequentlyfor thisspeciesbelongedtothegenusGlomeris

(75.6%).

AbouthalfofG.pyrenaicuspreybelongedtoEphemeroptera,

Ple-copteraandTrichopteraorderswhileonly16.6%ofpreybelongedto

theseordersforN.fodiens.Theproportionofexclusivelyterrestrial

preywashigherforN.fodiens(70.8±29.4%)thanforG.pyrenaicus

(20.6±30.5%),whiletheproportionofpreywithaquaticand

ter-restrialstageswashigherforG.pyrenaicus(74.6±31.4%)thanforN.

fodiens(26.1±28.3%).Exclusivelyaquaticpreyweremarginalfor

bothspecies.

Amongthe309identifiedgenerainthefaecesofbothmammals,

only90generawereconsumedbybothG.pyrenaicusandN.fodiens.

Thepreytaxaconsumedbyonlyoneofthetwospeciesweremostly

exclusivelyterrestrialgenera(52and80%inG.pyrenaicusandN.

fodiensfaeces,respectively).

Preycompositionoffaeceswassignificantlydifferentbetween

G.pyrenaicusandN.fodiensonthefirstaxisoftheCA(Student:

t=14.2,df=149.2,p<0.001).Thisdifferencecouldbeduetothe

majorityofterrestrialpreyinN.fodiensfaecesincontrastwithprey

withbothaquaticandterrestrialstagesfoundmorefrequentlyin

G.pyrenaicusfaeces(Fig.2).

Aquaticmacroinvertebratesavailability

Inthe27 siteswherestreaminvertebratesweresampled,G.

pyrenaicusandN.fodiensconsumedrespectively81and88

inver-tebratefamiliesintotaloutofwhich40and25familiesincluded

invertebrateswithatleastoneaquaticstageintheirlifecycle.

Fromstreaminvertebratessamples,atotalof51different

inver-tebratefamilieswereidentified(27±5persite)amongwhich42

familiesofInsecta,1Malacostracafamily,1Hydracarinafamily,2

Gastropodafamilies,1Bivalviafamily,1flatwormfamily,2

Clitel-latafamiliesand1Nematodesfamily.Insectataxahadthehighest

meandensitiesintheSurbersamples(Fig.3a).

Nineinvertebratefamilies(Rhagionidae,Caenidae,

Mermithi-dae, Planariidae, Leptoceridae, Gyrinidae, Calopterygidae,

Hydrophilidae,Psephenidae)wereexcludedfromfurtheranalyses

as they were found in the Surber samples and in faeces with

FOstream and FOdiet below 5%. Conversely, one-quarter of the

invertebratefamilieswithatleastoneaquaticstagefoundinthe

faecesofbothG.pyrenaicusandN.fodienswerenotfoundinthe

invertebratessamples.Thisconcerned9familiesoutof40forG.

pyrenaicusand5outof25familiesforN.fodiens.However,these

familieshada FOdietbelow10%inbothdiets,exceptthefamily

Anthomyiidae(20%inG.pyrenaicusdietand10.5% inN.fodiens

diet)andThaumaleidae(10.5%inN.fodiensdiet),andwerethus

alsoexcludedfromfurtheranalyses.

Densitiesofavailableinvertebrateswerenotsignificantly

differ-entbetweentheGalemysalonesites,theNeomysalonesitesandthe

Galemys+Neomyssites(Wilcoxonsign-rankedtests:alladjusted

p>0.05)allowingthecomparisonofinvertebratescontentin

fae-cescollectedinthedifferentcategoriesofsites.Forty-sixfamilies

and 50familieswereavailablein Galemysalone sitesand

Gale-mys+Neomyssitesrespectively,including45familiescommonto

bothtypesofsites.

Preyselectivitybetweenthetwomammals

Overall,themostfrequentlyconsumedpreybyG.pyrenaicus

corresponded to the most frequent and abundant invertebrate

taxa in streams (Fig. 3a and b). Seven out of the nine most

abundantpreywereconsumedinaccordancewiththefrequency

of occurrence and density estimated in the streams

Table1

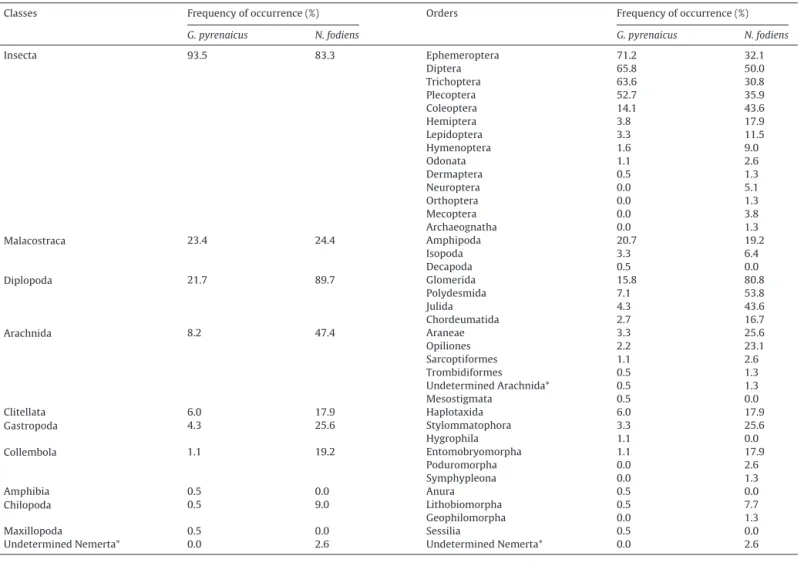

Preytaxaidentifiedwithpositivematches(≥80%)from184faecesofG.pyrenaicusand78faecesofN.fodienscollectedinthestudyarea.Thefrequencyofoccurrence(%of faecescontainingtheprey)isdisplayed.SeeAppendixAinthesupplementarymaterialforthefulllistoftaxaatthefamilyandgenuslevel.*indicatesmisidentifiedtaxaby geneticdatabases.

Classes Frequencyofoccurrence(%) Orders Frequencyofoccurrence(%)

G.pyrenaicus N.fodiens G.pyrenaicus N.fodiens

Insecta 93.5 83.3 Ephemeroptera 71.2 32.1 Diptera 65.8 50.0 Trichoptera 63.6 30.8 Plecoptera 52.7 35.9 Coleoptera 14.1 43.6 Hemiptera 3.8 17.9 Lepidoptera 3.3 11.5 Hymenoptera 1.6 9.0 Odonata 1.1 2.6 Dermaptera 0.5 1.3 Neuroptera 0.0 5.1 Orthoptera 0.0 1.3 Mecoptera 0.0 3.8 Archaeognatha 0.0 1.3 Malacostraca 23.4 24.4 Amphipoda 20.7 19.2 Isopoda 3.3 6.4 Decapoda 0.5 0.0 Diplopoda 21.7 89.7 Glomerida 15.8 80.8 Polydesmida 7.1 53.8 Julida 4.3 43.6 Chordeumatida 2.7 16.7 Arachnida 8.2 47.4 Araneae 3.3 25.6 Opiliones 2.2 23.1 Sarcoptiformes 1.1 2.6 Trombidiformes 0.5 1.3 UndeterminedArachnida* 0.5 1.3 Mesostigmata 0.5 0.0 Clitellata 6.0 17.9 Haplotaxida 6.0 17.9 Gastropoda 4.3 25.6 Stylommatophora 3.3 25.6 Hygrophila 1.1 0.0 Collembola 1.1 19.2 Entomobryomorpha 1.1 17.9 Poduromorpha 0.0 2.6 Symphypleona 0.0 1.3 Amphibia 0.5 0.0 Anura 0.5 0.0 Chilopoda 0.5 9.0 Lithobiomorpha 0.5 7.7 Geophilomorpha 0.0 1.3 Maxillopoda 0.5 0.0 Sessilia 0.5 0.0

UndeterminedNemerta* 0.0 2.6 UndeterminedNemerta* 0.0 2.6

Fig.2.CorrespondenceAnalysis(CA)computedonthefrequentlyusedpreytaxa(FOdiet>5%)derivedfrom184G.pyrenaicusand78N.fodiensfaeces.(a)Projectionsofprey taxaonthefirst(8.4%)andsecond(4.2%)axisoftheCA:preytaxaaredepicteddifferentlyaccordingtothetypeofhabitatduringtheirlifecycle.(b)ProjectionsofG.pyrenaicus (“Galemys”)andN.fodiens(“Neomys”)faecesonthefirstfactorialplane.

Fig.3. PreyselectivityforG.pyrenaicus(Galemys;darkbarsfor25Galemyssites)andN.fodiens(Neomys,lightbarsfor19Neomyssites).(a)Meandensitiesofinvertebrate preyintheSurbersamplesforeachsiteinGalemysandNeomyssites.(b)Frequencyofoccurrenceofprey(FOdiet)incollectedfaeces.(c)Ivlev’selectivityindex.Theelectivity indexisbasedonthefrequencyofpreyinfaecesrelativetopreyavailableinstreamswherethefaeceswerecollected.Blacktrianglesidentifyexclusivelyaquaticinvertebrate familiesasopposedtofamilieswithouttrianglesthatincludeinvertebrateswithatleastoneaquaticstageandoneterrestrialstageintheirlifecycle.

Simulidae,Nemouridae;Fig.3c). N.fodiensconsumed

Gammari-daeaccordingtotheirrelativeamountinthestreamsandavoided

theothermostabundantfamilies.

However,mostinvertebratefamiliessampledinstreamswere

avoidedbyG.pyrenaicusandN.fodienswithnegativeIvlev’svalues

below −0.25 for 22 and 31 available taxa out of 41,

respec-tively(Fig.3c).BothG.pyrenaicusandN.fodiensseemedtoavoid

Brachycentridae and Elmidae prey in spite of their high

den-sities in streams. An active selection of invertebrate prey was

highlightedforsevenfamiliesforG.pyrenaicus(Cordulegastridae,

Blephariceridae,Tipulidae,Scirtidae,Limnephilidae,Psychodidae,

Ephemeridae)andfivefamiliesforN.fodiens(Cordulegastridae

Dix-idae,Limnephilidae,Scirtidae,Tipulidae).

Trophicoverlapbetweenmammals

ThedietaryoverlapbetweenG.pyrenaicusandN.fodienswas

moderateatthegenus(Piankaindex=0.4)andfamily(0.5)levels.

NodifferenceintheFOdietofthepreyfoundinG.pyrenaicus

faeces wasdetectedat thefamily level betweenthesites with

orwithoutthepresenceofN.fodiens(Wilcoxonsign-rankedtest:

V=2748,p=0.3).Whenconsideringallconsumedpreyfamilies,72

wereconsumedbyG.pyrenaicusinGalemysalonesites(38with

FOdiet>5%)and86inGalemys+Neomyssites(44withFOdiet>5%).

Only47 taxawereconsumed inboth categoriesof sites.Ratios

betweennumbersofrareprey(i.e.,FOdiet<5%)andfrequentprey

(i.e.,FOdiet>5%)inG.pyrenaicusdietweresimilar(around50%)in

GalemysalonesitesandinGalemys+Neomyssites.

Discussion

NovelinsightsintothedietofG.pyrenaicusandN.fodiensduring

summer

This study provides additional support to the usefulness of

moleculargenetictoolsindietanalyses,asitprovidesanenhanced

identificationofpreycontentfromindirectsignsofpresence(i.e.,

faeces)ofpredators.Theproportionoffaecesmisidentificationin

thefield(i.e.,belongingtootherhostspecies:11%)orunidentified

faecesinthelaboratory(29%)areconsistentwithpreviousstudies

ofG.pyrenaicusdiet(Gillet,2015)confirmingtheissuesarisingfrom

visualidentificationoffaecesandDNAextractionfromdegraded

faeces.

Fromthe194invertebrategeneraidentifiedinthefaecesofG.

pyrenaicusinthepresentstudy,only61werecommonwiththe156

generaidentifiedinapreviousstudyusingsimilargeneticmethods

butconductedinthewholeFrenchPyrenees(Gillet,2015;Biffietal.,

2017).Newlyidentifiedpreyincludedanamphibian,aquaticand

terrestrialsnails,leeches,earwigs,Hydracarina,Chilopoda,

Maxil-lopodaandCollembola.

Thisstudyalsoprovidesunprecedentedinsightsintothe

sum-mertrophicnicheofN.fodiens,byidentifyingpreyidentityatthe

familyandgenuslevelsforthefirsttime(butseeattheorderlevel:

Castiénand Gosálbez,1999; Churchfield,1985;Churchfield and Rychlik,2006).Inaccordancewithpreviousstudiesconductedat

ahighertaxonomiclevel,wefoundthatN.fodiensfedon

terres-trialpreyatalargerextentthanG.pyrenaicus,withadominance

Ephemeroptera,PlecopteraandTrichopterawaslow(about17%)

comparedtoG.pyrenaicus(55%).

Thedensity and species composition of streaminvertebrate

communitiesdescribedinthisstudyareconsistentwithprevious

reportsoffreshwaterinvertebratefaunaoftheFrenchPyrenees

(e.g.,Brownetal.,2006;Finnetal.,2013).BothG.pyrenaicusand

N.fodiensexhibitedrathernon-selectiveforagingstrategiesasthe

mostfrequentlyconsumedinvertebrateswerealsothemost

fre-quentandabundantinthestreams.Thissupportedageneralistdiet

forbothspeciesinthestudyareaalthoughasignificantnumberof

taxawereconsumedinlowerorhigherfrequenciesthanexpected

(Fig.3).

N.fodiensavoidedahighernumberofpreyandactivelyselected

asmallernumberofpreythanG.pyrenaicusintheaquatic

envi-ronment.Thissupportsthedifferenceintrophicnichesbetween

thetwospecies,withmoreterrestrialtaxainN.fodiensdiet

com-paredwith G.pyrenaicus. This latter species hasmorphological

features adapted to livein aquatic environments (e.g.,webbed

feet,Palmeirim,1983;Puisségur,1935;highdivingskills:1–4min,

Richard and Micheau, 1975 compared to 3–24s for N. fodiens,

Lardet,1988;Mendes-SoaresandRychlik,2009)thatlikelyresult

inabetterefficiencyinthecaptureofaquaticpreythanN.fodiens.

Foragingefficiencymaydeterminepreyselectivityinorderto

maximiseindividualsuccess.Itdependsonthebalancebetween

theenergyprovidedbypreyconsumptionandtheenergeticcosts

offoragingunderwater. Themostvaluableresourcesmaythus

correspond to easy-to-catch prey with low mobility (e.g.,

Tri-choptera)and/orhighabundance(e.g.,Gammaridae),soft-bodied

preythatcanbecompletelydigested(e.g.,incontrastwithsmall

and chitinous Hydracarina or Coleoptera,Costa et al., 2015) or

largeprey(Bertrand,1994).Inthisstudy,invertebrateswithhard

andchitinousbodies(e.g.Elmidae,HydraenidaeHydracarina)and

hard casesmadeof wood(Brachycentridae) or mineral

materi-als(Glossossomatidae,Sericostomatidae)wereavoidedbybothG.

pyrenaicusandN.fodiens.

SomeofourresultsaboutpreyselectivitybyG.pyrenaicus

con-tradictpreviousobservationsbyBertrand(1994)andSantamarina

(1993).Forinstance,Rhyacophilidaewereavoidedand

Limnephil-idaeactivelyselectedbyG.pyrenaicusinourstudywhereasthe

oppositewas observedby Bertrand(1994). Chironomidaewere

avoided and Sericostomatidae activelyselected in Santamarina

(1993)whereaswefoundtheoppositepatternforthesefamilies.

Thesedifferencesmaybeduetodifferentsamplingmethods

(stom-achanalysesvs.digestedremainsinfaecesvs.molecularanalyses)

aswellassamplesizes.Theymayalsoreflectthegeneralistdietof

G.pyrenaicusthatmayvarybetweenregions(i.e.,acatchmentof

Spainvs.thewholeFrenchPyreneesvs.asub-regionoftheFrench

Pyrenees)andseasons(Santamarina,1993).Finally,the

variabil-ityinlife-historytraitswithinandbetweeninvertebratespeciesof

thesamefamilyorgenus(e.g.,developmentstage,bodysize,local

adaptations)mayinfluencetheirexposuretopredation.

Trophicoverlapbetweenmammals

Thefaecesandaquaticinvertebratessamplingswereconducted

duringsummerwhenmany late instarsof aquaticinsects have

emergedfrommountainstreamsandlefttheaquaticenvironment

(Fürederet al.,2004).Invertebratecommunities are dominated

bysmall-sizedinvertebratesforthisperiod.Thisimpoverishment

inpreydiversityanddensitymayexacerbatethetrophicoverlap

betweentheirpredators,suchasG.pyrenaicusandN.fodiens,

com-paredtotherestoftheyear.Inspiteofthis,thePianka’sindex

oftrophicoverlapbetweenthetwospeciesequalled0.4

indicat-ingasignificantbutratherlowoverlapinthesummerdiets.This

valueisconsistentwithapreviousestimateofoverlap(Castiénand

Gosálbez,1999).

G.pyrenaicusconsumedalargernumberofdifferentpreyinthe

siteswhereN.fodienswasalsopresent.Thisincreasewasdrivenby

ahigherconsumptionofterrestrialtaxabutwasnotlinkedtoany

increaseinrarepreyconsumptionasratiosofrareprey/frequent

preyweresimilarinsiteswithorwithoutN.fodiens.However,no

significantdifferencewasfoundindietcompositionofG.pyrenaicus

betweensiteswhereN.fodienswasdetectedornot.Alltheseresults

suggestnoevidenceofashiftofG.pyrenaicusdiettowards

sub-optimalpreyinthepresenceofanotherinsectivorespecieswith

similarfeedingstrategies.

Theabsenceof shiftin G.pyrenaicusdiet inthepresence of

N.fodienscouldresultfromthenon-limitingtrophicresourcesin

streamsand/oronterrestrialhabitatsduringsummer.Actually,the

measureofnicheoverlapmaymostlyreflectthepotential

compe-titioninthecaseoflimitingresources(Abrams,1980).

ItcouldalsobeduetoresourcepartitioningbetweenG.

pyre-naicusandN.fodiens.First,asynchronyofseasonalordailyactivity

periodsmayplayanimportantroleinresourcepartitioningand

facilitatecohabitation(e.g.,Harringtonet al.,2009).A temporal

shiftofnichehasbeenobservedinherbivorestoreducethelength

ofthetrophic overlapatwaterholesduringaridseasons(Valeix

etal.,2007).RadiotrackingconductedonafewindividualsofG.

pyrenaicusandN.fodiensseemstoindicatepolyphasicactivity

pat-terns(Lardet,1988;Meleroetal.,2014;Stone,1987)withasimilar

timingofactivityduringdayandnightperiods.Thissuggeststhat

thismechanismisprobablynotinvolvedintheresource

partition-ingbetweenthesetwospecies.

Second,successfulresourcepartitioningmayberelatedtohow

thepredatorsaccesstofoodresourcesaccordingtotheirforaging

strategies. Thesegregationof trophic nichesbased on

differen-tiation of foraging modes and foraging micro-habitats is well

documentedamongshrews(e.g.,ChurchfieldandRychlik,2006;

ChurchfieldandSheftel,199).First,G.pyrenaicusandN.fodienshave

differentbodysize(i.e.,10–15cmvs.7–9cmwithoutthetailforG.

pyrenaicusandN.fodiens,respectively)andmass(i.e.,50–60gvs.

8–17gforG.pyrenaicusandN.fodiens,respectively).Duetothis

differenceofsize,thetwospeciescouldtargetcontrasted

develop-mentstageandpreysizewithinagiventaxa,asitisknowntoallow

resource partitioning among shrew species (Churchfield et al.,

1999).Second,theuseofdifferenthabitatstratawasalsoidentified

insmallmammalcommunitiestomodulatetheintensityof

inter-specificcompetition(CastiénandGosálbez,1999;Churchfieldand

Sheftel,1994;Rychlik,1997).Specializationonparticular

micro-habitatsinstreamsisalsoknownforothersemi-aquaticmammals.

Forinstance,theplatypusOrnithorhynchusanatinusdoesnot

allo-cateanequalforagingefforttobenthicmacroinvertebratesacross

allhabitats,itspreferencegoingtopoolsandlittoralmarginsrather

thanriffles(McLachlan-Troupetal.,2010).Theoveralllow

selec-tivity,activeselectionoravoidanceofdifferenttaxa,togetherwith

thedistincttrophicnicheweobservedinthewholestudyareain

G.pyrenaicusandN.fodiens,suggestthattheyusedistinctforaging

micro-habitats(CastiénandGosálbez,1999)withinthestreamand

riparianmosaic.Otheraquaticpredatorssuchasthebrowntrout

S.truttacouldhavehigherdietoverlapwithG.pyrenaicusdueto

theirbroaduseofhabitatswithinstreamsandhighlyopportunistic

feedingstrategies(GillerandGreenberg,2015).

Methodologicalconsiderationsandperspectives

Whilemolecularmethodsprovideanenhancedidentificationof

preycomparedtotraditionalmethods(i.e.,visualinspectionofprey

remainsingutsorfaeces),theyalsohavesomeshortcomings.First,

identifyingmanyadditionalpreytaxawithmoleculartools

com-paredtotraditionalmethodsisconsistentwithClareetal.(2014)

who suggest that preyoccurrence data obtainedfrom

preyandoverestimaterareprey(Clareetal.,2014;Krügeretal.,

2014).Nevertheless,20taxaidentified,suchasCollembolaor

sev-eralgenusoftheTachinidaefamily,areunlikelytobedirectpreyof

G.pyrenaicusorN.fodiens,astheyarepartofthesoilmicrofaunaor

areinvertebrateparasites.Othertaxa,suchassomeAnthomyiidae

(e.g.Polietes)orsmallterrestrialColeoptera,mayhavebeen

col-lectedwiththefaecesastheymaydevelopatthelarvalstageorfeed

onscat.Finally,taxaidentifiedaspreycouldhavebeenpassively

ingestedwiththeconsumptionofpredatororscavenger

inverte-brates(e.g.Trichoptera,Plecoptera,Odonata).Thiscontributesto

thedebateaboutthehighsensitivityofnext-generation

sequenc-ingmethodsandthedetectionofsecondarypredation(Sheppard

etal.,2005).

Second,moleculardatadonotgiveinformationonthestage

orsizeatwhichpreyareconsumed.Thisisaparticularlystrong

limitationwhen(i)feedingstrategiesareadapted tothemouth

morphologyandsizeofthepredatoror(ii)preyexhibit

impor-tantvariationinhabitatuseduringtheirlifecyclesuchasmany

aquaticinvertebratespecies.Giventherelativeshortnessofthe

terrestrialstageincomparison withtheaquaticstagefor many

invertebratespecies,theprobabilitythat invertebratesfoundin

thefaeceswereconsumedattheaquaticstage(oratthetimeof

emergence)remainshigh,whichissupportedbyprevious

morpho-logicalidentificationofpreyitemsinfaecalsamples(Trichoptera;

e.g.,Bertrand,1994;DuPasquierandCantoni,1992).The

combi-nationofmolecularandtraditionalmethodsofpreyidentification

seemsthusimportanttobringdetailedinformationontheidentity,

sizeandstageofeatenprey.

Third,themoleculardataweuseddonotallowaquantitative

assessmentofthepreyconsumed(e.g.relativeandabsolute

abun-dance/biomass ofdifferenttaxa). Klareetal. (2011)stated that

suchqualitativeestimates(i.e.,presence-absenceandfrequencyof

occurrenceofprey)tendtooverestimatenichebreadthanddietary

overlapsbetweenspeciesleadingpotentiallytounreliable

conclu-sions.However,theyalsopointedoutthatsuchbiasremainslow

whenthedietsofthecomparedspeciesarecomposedofsimilar

taxonomicgroupsofprey,whichisthecaseforG.pyrenaicusandN.

fodiens.Moreover,thelikelybiasindietestimationduetotheuse

offrequenciesofoccurrenceissimilarbetweenG.pyrenaicusand

N.fodienswhichenablesareliablequalitativecomparisonofdiet

overlapandpreyselectionpatternsintermsofpreyidentity.Thisis

supportedbythePiankaindexoftrophicnicheoverlapquantified

inthisstudywhichisconsistentwithpreviousobservationsbased

onquantitativemethodsofpreyestimates.

Despitethoselimitations,molecularmethodsprovedefficiency

intheidentificationofahighlydiversedietforG.pyrenaicusand

N.fodiens that werehighlighted toexhibit a generalist feeding

behaviour.Thissuggeststhattheidentityofpreytaxaisnotthe

most important criteria for both mammals prey selection and

thattheymayexhibitsometolerancetovariationin prey

com-munitycomposition.Hence,stream communitychanges dueto

anthropogenicimpactsonriverecosystemsshouldhavemoderate

consequences(Costaetal.,2015)aslongasfoodresourcesremain

abundantenoughintheirrespectiveforaginghabitats.However,

pressuresonpreycommunitiescouldincreasethetrophicoverlap

betweenthetwospeciesaswellaswithotherspotential

competi-tors.

ThisstudyalsostressedthatthepresenceofN.fodiensdidnot

affectG.pyrenaicuspreyselection.However,thehigherproportion

ofexclusivelyterrestrialpreyinN.fodiensdietfoundhere

com-paredtootherdietarystudies(e.g.Churchfield,1984;DuPasquier

andCantoni, 1992)maysuggesta shiftinthedietofN.fodiens

towardsamoreterrestrialnicheinpresenceofG.pyrenaicus.The

verysmallnumberofsiteshostingN.fodienswithoutG.pyrenaicus

didunfortunatelypreventustotestforthispotentialcompetitive

interaction.

Identifyingmorefinelytheforagingmicro-habitatsofG.

pyre-naicusandN.fodiens,comparingthedietofN.fodiensinpresence

andabsenceofG.pyrenaicusandobservingtheirbehavioural

inter-actionsinthefieldalongtheyearshouldbefurtherinvestigatedin

thelightofterrestrialinvertebratessamplingandtheuseofdietary

quantitative data (e.g.abundance or biomass of prey in scats).

Thiswouldimproveourknowledgeaboutmechanisms

facilitat-ingtheircohabitationorcausingpotentialcompetitiveinteractions

andtheirvulnerabilitytohabitatandtrophicresourcealterations.

Acknowledgements

Wearegratefultoallpeoplewhohelpedcollectingdatainthe

field:C.Dupuyds,M.Alvarez.,C.Lauzeral,F.Colas,F.JulienandV.

Lacaze.Wealsothankthe“Conservatoired’EspacesNaturels

Midi-Pyrénées”(CEN-MP),especiallyM.NémozandF.Blanc,fortheir

preciousadviceatmanystepsofthestudy.Thisstudywasfunded

byANRT(Cifren◦2011/1018),EDF(ElectricitédeFrance)andthe

EuropeanUnion(FEDER)inthecontextoftheLIFE+Nature

pro-grammedevotedtoG.pyrenaicus(LIFE13NAT/FR/000092).M.Biffi

wassupportedbyaPhDfellowshipgrantedbythe“EcoleDoctorale

Sciencesdel’Univers,del’Environnementetdel’Espace”(SDU2E)

attheUniversityofToulouse.

AppendixA. Supplementarydata

Supplementarydataassociatedwiththisarticlecanbefound,in

theonlineversion,athttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2017.09.

001.

References

Abrams,P.,1980.Somecommentsonmeasuringnicheoverlap.Ecology61,44–49. André,A.,Mouton,A.,Millien,V.,Michaux,J.,2017.Livermicrobiomeof

Peromyscusleucopus,akeyreservoirhostspeciesforemerginginfectious diseasesinNorthAmerica.Infect.Genet.Evol.52,10–18.

Aymerich,P.,Gosàlbez,J.,2015.Evidenciasderegresiónlocaldeldesmánibérico (Galemyspyrenaicus)enlosPirineosmeridionales.Galemys27,31–40. Aymerich,P.,Gosálbez,J.,2004.Laprospeccióndeexcrementoscomometodología

paraelestudiodeladistribucióndelosmusga ˜nos(Neomyssp.).Galemys16, 83–90.

Bertrand,A.,1994.Répartitiongéographiqueetécologiealimentairedudesman desPyrénées,Galemyspyrenaicus(Geoffroy,1811)danslesPyrénées franc¸aises.Thèsededoctorat.UniversitéPaulSabatierdeToulouse(50pp). Biffi,M.,Charbonnel,A.,Buisson,L.,Blanc,F.,Némoz,M.,Laffaille,P.,2016.Spatial

differencesacrosstheFrenchPyreneesintheuseoflocalhabitatbythe endangeredsemi-aquaticPyreneandesman(Galemyspyrenaicus).Aquat. Conserv.Mar.Freshw.Ecosyst.26,761–774.

Biffi,M.,Gillet,F.,Laffaille,P.,Colas,F.,Aulagnier,A.,Blanc,F.,Galan,M., Tiouchichine,M.-L.,Némoz,M.,Buisson,L.,Michaux,J.R.,2017.Novelinsights intothedietofthePyreneandesman(Galemyspyrenaicus)using

next-generationsequencingmolecularanalyses.J.Mammal.,http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jmammal/gyx070.

Brown,L.E.,Milner,A.M.,Hannah,D.M.,2006.Stabilityandpersistenceofalpine streammacroinvertebratecommunitiesandtheroleofphysicochemical habitatvariables.Hydrobiologia560,159–173.

Cantoni,D.,1993.Socialandspatialorganizationoffree-rangingshrews,Sorex coronatusandNeomysfodiens(Insectivora,Mammalia).Anim.Behav.45, 975–995.

Castién,E.,Gosálbez,J.,1995.DietofGalemyspyrenaicus(Geoffroy,1811)inthe NorthoftheIberianpeninsula.Neth.J.Zool.45,422–430.

Castién,E.,Gosálbez,J.,1999.Habitatandfoodpreferencesinaguildof insectivorousmammalsintheWesternPyrenees.ActaTheriol.44,1–13. Charbonnel,A.,D’Amico,F.,Besnard,A.,Blanc,F.,Buisson,L.,Némoz,M.,Laffaille,

P.,2014.Spatialreplicatesasanalternativetotemporalreplicatesfor occupancymodellingwhensurveysarebasedonlinearfeaturesofthe landscape.J.Appl.Ecol.51,1425–1433.

Charbonnel,A.,Buisson,L.,Biffi,M.,D’Amico,F.,Besnard,A.,Aulagnier,S.,Blanc,F., Gillet,F.,Lacaze,V.,Michaux,J.R.,Némoz,M.,Pagé,C.,Sanchez-Perez,J.M., Sauvage,S.,Laffaille,P.,2015.Integratinghydrologicalfeaturesandgenetically validatedoccurrencedatainoccupancymodellingofanendemicand endangeredsemi-aquaticmammal,Galemyspyrenaicus,inaPyrenean catchment.Biol.Conserv.184,182–192.

Charbonnel,A.,Laffaille,P.,Biffi,M.,Blanc,F.,Maire,A.,Némoz,M.,Sanchez-Perez, J.M.,Sauvage,S.,Buisson,L.,2016.Canrecentglobalchangesexplainthe

dramaticrangecontractionofanendangeredsemi-aquaticmammalspeciesin theFrenchPyrenees?PLoSOne11,e0159941.

Churchfield,S.,Rychlik,L.,2006.DietsandcoexistenceinNeomysandSorexshrews inBiałowie ˙zaforest,easternPoland.J.Zool.269,381–390.

Churchfield,S.,Sheftel,B.I.,1994.Foodnicheoverlapandecologicalseparationina multi-speciescommunityofshrewsintheSiberiantaiga.J.Zool.234,105–124. Churchfield,S.,Nesterenko,V.A.,Shvarts,E.A.,1999.Foodnicheoverlapand

ecologicalseparationamongstsixspeciesofcoexistingforestshrews (Insectivora:soricidae)intheRussianFarEast.J.Zool.248,349–359. Churchfield,S.,1984.Aninvestigationofthepopulationecologyofsyntopic

shrewsinhabitingwater-cressbeds.J.Zool.Lond.204,229–240.

Churchfield,S.,1985.ThefeedingecologyoftheEuropeanwatershrew.Mammal Rev.15,13–21.

Clare,E.L.,Symondson,W.O.C.,Broders,H.,Fabianek,F.,Fraser,E.E.,MacKenzie,A., Boughen,A.,Hamilton,R.,Willis,C.K.R.,Martinez-Nu ˜nez,F.,Menzies,A.K., Norquay,K.J.O.,Brigham,M.,Poissant,J.,Rintoul,J.,Barclay,R.M.R.,Reimer,J.P., 2014.ThedietofMyotislucifugusacrossCanada:assessingforagingqualityand dietvariability.Mol.Ecol.23,3618–3632.

Costa,A.,Salvidio,S.,Posillico,M.,Matteucci,G.,DeCinti,B.,Romano,A.,2015. Generalisationwithinspecialization:inter-individualdietvariationintheonly specializedsalamanderintheworld.Sci.Rep.5,13260.

DuPasquier,A.,Cantoni,D.,1992.Shiftsinbenthicmacroinvertebratecommunity andfoodhabitsofwatershrew,Neomysfodiens(Soricidae,Insectivora).Acta OEcologicaOEcal.Gener.13,81–99.

Dudgeon,D.,Arthington,A.H.,Gessner,M.O.,Kawabata,Z.-I.,Knowler,D.J., Lévêque,C.,Naiman,R.J.,Prieur-Richard,A.-H.,Soto,D.,Stiassny,M.L.J., Sullivan,C.A.,2006.Freshwaterbiodiversity:importance,threats,statusand conservationchallenges.Biol.Rev.81,163–182.

Edgar,R.C.,2010.SearchandclusteringordersofmagnitudefasterthanBLAST. Bioinforma.Oxf.Engl.26,2460–2461.

Escoda,L.,González-Esteban,J.,Gómez,A.,Castresana,J.,2017.Usingrelatedness networkstoinfercontemporarydispersal:applicationtotheendangered mammalGalemyspyrenaicus.Mol.Ecol.,http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mec. 14133.

Füreder,L.,Wallinger,M.,Burger,R.,2004.Longitudinalandseasonalpatternof insectemergenceinalpinestreams.Aquat.Ecol.39,67–78.

Fernandes,M.,Herrero,J.,Aulagnier,S.,Amori,G.,2008.GalemysPyrenaicus.The IUCNRedListofThreatenedSpecies.Version2014.2(<www.iucnredlist.org> Downloadedon1June2014)http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS. T8826A12934876.en.

Finn,D.S.,Khamis,K.,Milner,A.M.,2013.Lossofsmallglacierswilldiminishbeta diversityinPyreneanstreamsattwolevelsofbiologicalorganization.Glob. Ecol.Biogeogr.22,40–51.

Giller,P.,Greenberg,L.,2015.Therelationshipbetweenindividualhabitatuseand dietinbrowntrout.Freshw.Biol.60,256–266.

Gillet,F.,Tiouchichine,M.-L.,Galan,M.,Blanc,F.,Némoz,M.,Aulagnier,S., Michaux,J.R.,2015.AnewmethodtoidentifytheendangeredPyrenean desman(Galemyspyrenaicus)andtostudyitsdiet,usingnextgeneration sequencingfromfaeces.Mamm.Biol.80,505–509.

Gillet,F.,2015.GénétiqueetbiologiedelaconservationdudesmandesPyrénées (Galemyspyrenaicus)enFrance.Thèsededoctorat,UniversitéPaulSabatierde Toulouse(France)/UniversitédeLiège(Belgique),228pp.

Gisbert,J.,García-Perea,R.,2014.Historiadelaregresióndeldesmánibérico Galemyspyrenaicus(É.GeoffroySaint-Hilaire,1811)enelSistemaCentral (PenínsulaIbérica).Conservationandmanagementofsemi-aquaticmammals ofsouthwesternEurope.MunibeMonogr.Nat.Ser.,3.,pp.19–35.

Greenwood,A.,Churchfield,S.,Hickey,C.,2002.Geographicaldistributionand habitatoccurrenceofthewatershrew(Neomysfodiens)intheWealdof South-EastEngland.MammalRev.32,40–50.

Haberl,W.,2002.Foodstorage,preyremainsandnotesonoccasionalvertebrates inthedietoftheEurasianwatershrew,Neomysfodiens.FoliaZool.51,93–102. Harrington,L.A.,Harrington,A.L.,Yamaguchi,N.,Thom,M.D.,Ferreras,P.,

Windham,T.R.,Macdonald,D.W.,2009.Theimpactofnativecompetitorsonan alieninvasive:temporalnicheshiftstoavoidinterspecificaggression?Ecology 90,1207–1216.

Hutchinson,G.E.,1957.Concludingremarks.ColdSpringHarb.Symp.Quant.Biol. 22,415–427.

Ivlev,V.S.,1961.ExperimentalEcologyofFeedingFishes.YaleUniversityPress, NewHaven,Connecticut(302pp).

Keckel,M.R.,Ansorge,H.,Stefen,C.,2014.Differencesinthemicrohabitat preferencesofNeomysfodiens(Pennant1771)andNeomysanomalusCabrera 1907inSaxony.Germany.ActaTheriol.59,485–494.

Klare,U.,Kamler,J.F.,Macdonald,D.W.,2011.Acomparisonandcritiqueof differentscat-analysismethodsfordeterminingcarnivorediet.Mammal Review41,294–312.

Krüger,F.,Clare,E.L.,Greif,S.,Siemers,B.M.,Symondson,W.O.C.,Sommer,R.S., 2014.Anintegrativeapproachtodetectsubtletrophicnichedifferentiationin thesympatrictrawlingbatspeciesMyotisdasycnemeandMyotisdaubentonii. Mol.Ecol.23,3657–3671.

Lardet,J.-P.,1988.Spatialbehaviourandactivitypatternsofthewatershrew Neomysfodiensinthefield.ActaTheriol.33,293–303.

Life+Desman,2013.TechnicalApplicationForms–ConservationoftheFrench PopulationsofGalemysPyrenaicusandItsPopulationsontheFrenchPyrénées (LIFE13NAT/FR/000092).274p.

McLachlan-Troup,T.A.,Dickman,C.R.,Grant,T.R.,2010.Dietanddietaryselectivity oftheplatypusinrelationtoseason,sexandmacroinvertebrateassemblages.J. Zool.280,237–246.

Melero,Y.,Aymerich,P.,Luque-Larena,J.J.,Gosálbez,J.,2012.Newinsightsinto socialandspaceusebehaviouroftheendangeredPyreneandesman(Galemys pyrenaicus).Eur.J.Wildl.Res.58,185–193.

Melero,Y.,Aymerich,P.,Santulli,G.,Gosálbez,J.,2014.Activityandspacepatterns ofPyreneandesman(Galemyspyrenaicus)suggestnon-aggressiveand non-territorialbehaviour.Eur.J.Wildl.Res.60,707–715.

Mendes-Soares,H.,Rychlik,L.,2009.Differencesinswimminganddivingabilities betweentwosympatricspeciesofwatershrews:Neomysanomalusand Neomysfodiens(Soricidae).J.Ethol.27,317–325.

Morueta-Holme,N.,Fløjgaard,C.,Svenning,J.-C.,2010.Climatechangerisksand conservationimplicationsforathreatenedsmall-rangemammalspecies.PLoS One5,e10360.

Muséumnationald’Histoirenaturelle[Ed].2003–2017.InventaireNationaldu PatrimoineNaturel.https://inpn.mnhn.fr.Accessed15May2016. Némoz,M.,Bertrand,A.,Sourie,M.,Arlot,P.,2011.Afrenchconservationaction

planforthepyreneandesmanGalemyspyrenaicus.Galemys23,47–50. OPIE-Benthos,2017.OfficePourlesInsectesetleurEnvironnement

(http://www.opie-benthos.fr/opie/insecte.php.Accessed15May2016). Palmeirim,J.M.,1983.Galemyspyrenaicus.Mamm.Species207,1–5. Parry,G.S.,Bodger,O.,McDonald,R.A.,Forman,D.W.,2013.Asystematic

re-samplingapproachtoassesstheprobabilityofdetectingottersLutralutra usingspraintsurveysonsmalllowlandrivers.Ecol.Inform.14,64–70(The analysisandapplicationofspatialecologicaldatatosupporttheconservation ofbiodiversity).

Pianka,E.R.,1973.Thestructureoflizardcommunities.Annu.Rev.Ecol.Syst.4, 53–74.

Pianka,E.R.,1974.Nicheoverlapanddiffusecompetition.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.71, 2141–2145.

Pompanon,F.,Deagle,B.E.,Symondson,W.O.C.,Brown,D.S.,Jarman,S.N.,Taberlet, P.,2012.Whoiseatingwhat:dietassessmentusingnextgeneration sequencing.Mol.Ecol.21,1931–1950.

Puisségur,C.,1935.RecherchessurleDesmandesPyrénées.Bull.Soc.Hist.Nat. Toulouse67,163–227.

RCoreTeam,2014.R:ALanguageandEnvironmentforStatisticalComputing.R FoundationforStatisticalComputing,Vienna,Austriahttp://www.R-project. org/.

Ratnasingham,S.,Hebert,P.D.N.,2007.BOLD:thebarcodeoflifedatasystem (www.barcodinglife.org).Mol.Ecol.Notes7,355–364.

Richard,P.B.,Micheau,C.,1975.Lecarrefourtrachéendansl’adaptationdudesman desPyrénées(Galemyspyrenaicus)àlaviedulc¸aquicole.Mammalia39, 467–478.

Rychlik,L.,1997.Differencesinforagingbehaviourbetweenwatershrews:Neomys anomalusandNeomysfodiens.ActaTheriol.42,351–386.

Rychlik,L.,2000.Habitatpreferencesoffoursympatricspeciesofshrews.Acta Theriol.45(Suppl.1),173–190.

Santamarina,J.,Guitian,J.,1988.Quelquesdonnéessurlerégimealimentairedu desman(Galemyspyrenaicus)danslenord-ouestdel’Espagne.Mammalia52, 302–307.

Santamarina,J.,1993.Feedingecologyofavertebrateassemblageinhabitinga streamofNWSpain(Riobo;Ullabasin).Hydrobiologia252,175–191. Sheppard,S.K.,Bell,J.,Sunderland,K.D.,Fenlon,J.,Skervin,D.,Symondson,W.O.C.,

2005.DetectionofsecondarypredationbyPCRanalysesofthegutcontentsof invertebrategeneralistpredators.Mol.Ecol.14,4461–4468.

Stone,R.D.,1987.TheactivitypatternsofthePyreneandesman(Galemys pyrenaicus)(Insectivora:talpidae),asdeterminedundernaturalconditions.J. Zool.213,95–106.

Tachet,H.,Richoux,P.,Bournaud,M.,Usseglio-Polatera,P.,2000.Invertébrésd’eau douce.Systématique,Biologie,Ecologie,CNRSEditions,Paris.

Valeix,M.,Chamaillé-Jammes,S.,Fritz,H.,2007.Interferencecompetitionand temporalnicheshifts:elephantsandherbivorecommunitiesatwaterholes. Oecologia153,739–748.

Wisz,M.S.,Pottier,J.,Kissling,W.D.,Pellissier,L.,Lenoir,J.,Damgaard,C.F., Dormann,C.F.,Forchhammer,M.C.,Grytnes,J.-A.,Guisan,A.,Heikkinen,R.K., Høye,T.T.,Kühn,I.,Luoto,M.,Maiorano,L.,Nilsson,M.-C.,Normand,S., Öckinger,E.,Schmidt,N.M.,Termansen,M.,Timmermann,A.,Wardle,D.A., Aastrup,P.,Svenning,J.-C.,2013.Theroleofbioticinteractionsinshaping distributionsandrealisedassemblagesofspecies:implicationsforspecies distributionmodelling.Biol.Rev.88,15–30.