Coping with mild inflammatory catamenial acne

A clinical and bioinstrumental split-face assessment

Ludivine Petit1, Claudine Pie´rard-Franchimont1, Emmanuelle Uhoda1, Vale´rie Vroome2, Geert Cauwenbergh2and Ge´rald E. Pie´rard1

1Department of Dermatopathology, University Hospital of Lie`ge, Belgium and2Barrier Therapeutics, Geel, Belgium

Background: Acne is a multifactorial disease exhibiting distinct clinical presentations. Among them, the catamenial type is a matter of concern for young women. Some oral contraceptives may help without, however, clearing the skin condition.

Aim: The present open study aimed at evaluating the effect of overnight applications of a paste made of petrolatum, 15% zinc oxide and 0.25% miconazole nitrate.

Method: The split-face trial was conducted in 35 women. A non-medicated cream was used as control. Clinical evalua-tions and biometrological assessments on cyanoacrylate follicular biopsies were performed monthly for 3 months. Comedometry and the density in autofluorescent follicular casts were used as analytical parameters. In addition, the five most severe cases at inclusion were tested at the completion of the study for follicular bacterial viability using dual flow cytometry.

Results: Compared with baseline and to the control hemi-face, the medicated paste brought significant improvement of acne. The number of papules and their redness were re-duced beginning with the first treatment phase. A reduction in the follicular fluorescence was yielded beginning with the second treatment phase. The ratios between injured and dead bacteria, on the one hand, and live bacteria, on the other hand were significantly increased at completion of the study.

Conclusion: A miconazole paste applied for 1 week at the end of the ovarian cycle has a beneficial effect on catame-nial acne.

Key words:acne – biometrology – comedometry – micona-zole – ovarian cycle

&Blackwell Munksgaard, 2004

Accepted for publication 5 April 2004

A

CNE VULGARISis one of the most common skindiseases. It has a mulifactorial origin affect-ing some of the pilosebaceous follicles of the face and trunk, particularly in adolescents and young adults. Increased sebum production, Propionibac-terium acnes hypercolonization, comedo forma-tion and follicular inflammaforma-tion are obviously involved in the lesions (1). However, the precise inflammatory pathogenesis is not entirely under-stood (2). This is particularly the case for recur-rent catamenial acne, which cannot be explained by sudden changes in the recognized factors underlying acne vulgaris. There is much varia-tion in the age of onset and the age of resoluvaria-tion of catamenial acne. Most often, it remains mild in severity. However, the perceived psychosocial impairment, which is highly subjective (3), is not unfrequently influenced by overrating acne severity by the affected young women.

Currently, there is a variety of topical and systemic drugs that counteract the main aspects of acne pathology. However, none of them targets

specifically catamenial acne with the exception of some oral contraceptives. Usually, these pharma-cological agents only bring slow improvement without completely clearing the disease (4–7). There is also much variation in the response of women to acne therapy. The success of the treat-ment depends on both the selection of the appro-priate medications and the compliance of the subject. Oral isotretinoin is contra-indicated in women with catamenial acne. Continuous cures of oral antibiotics show efficacy (8, 9), but they are not recommended due to bacterial resistance that may occur during long-term treatment (8– 10). Most of the classical topical treatments bring no satisfactory inhibition of the crops of catame-nial acne, most probably because they are applied for a too short period of time. In addition, they target pathomechanisms that are not directly responsible for the specific presentation of cata-menial acne. Hence, it would be advisable to look for safe topical formulations that could bring a fast relief of inflammatory acne papules without

necessarily acting upon the underlying chronic acne-prone status.

The present clinical and bioinstrumental study aimed at assessing the effect of a non-steroidal, antibiotic-free anti-inflammatory paste on cata-menial acne resistant to oral contraceptives.

Patients and Methods

This open, single center, outpatient study was conducted in accordance with the Declaraton of Helsinki. The protocol was reviewed by the local Ethics Committee. A total of 35 students and qualified nurses aged from 19 to 25 years were enrolled after giving their written informed con-sent. All the patients complained from mild acne corresponding to grades 2 or 3 according to the Leeds revised acne grading system (11). The medical history was reviewed for each volunteer and did not reveal any other relevant finding. All the volunteers suffered from acne lesions recur-ring in catamenial crops for at least 2 years. They were on oral contraceptive for 10 months to 7 years. The current pills contained the 19-nortes-toserone derivatives desogestrel or gestodene, which had been shown to improve acne in pre-vious clinical studies (4, 5).

The oral contraceptive was kept unchanged while the volunteers entered a 3-month split-face assessment of the effect of a medicated paste on the inflammatory acne papules. The paste made of petrolatum, 15% zinc oxide and 0.25% miconazole nitrate (Zimycans

, Barrier Therapeu-tics, Geel, Belgium). Concomitant treatments tar-getting acne were prohibited. The test medication was applied once daily in the evening for 1 week on a randomized hemiface; the treatment started from day 24 of the ovarian cycle to end on day 2 of the following one. The symmetrical facial area received an unmedicated formulation (Eucerins

, Beiersdorf, Brussels, Belgium) to serve as control for any placebo effect. The ingredients are listed in Table 1. Clinical and bioinstrumental assessments were performed monthly at day 3 of each cycle.

Acne papules were counted. Their redness was measured using an advanced version of the Visi-Chroma (Biophotonics, Lessines, Belgium). As shown using an older version (12), this device allows to measure skin colors, in particular para-meter a*on small spots. The median value of all the papules was calculated. Cyanoacrylate skin surface strippings (CSSS) were used to collect follicular casts as previously described (4, 8,

13–17). In short, they were collected from both cheeks using plastic strips (Melinex Os

, Imperial Chemical Industries, London, UK) coated with

cyanoacrylate adhesive (Superglues

, Loctite, Brussels, Belgium). Image analysis was per-formed on these CSSS following the comedome-try procedure (4, 8, 13–17) in order to assess the microcomedo density and their cumulative size/ cm2 of skin surface. An indication of the amount of P. acnes was also determined on the same CSSS by detecting the porphyrin-induced follicular fluorescence (18, 19). The percentage of fluores-cent follicular casts seen under fluorescence mi-croscopy was calculated. In addition, the five most severe acne cases at inclusion (i.e. exhibiting more than 20 papules on the face) were selected for quantitative microbiology. This procedure was applied as previously described (4, 8) to the CSSS harvested at the last evaluation session. In short, the follicular casts were scraped from the CSSS using a sterile scalpel. The collected mate-rial was dispersed in sterile PBS before filtering through a gauze to remove clumps of corneo-cytes. Equal volumes of the two fluorescent

reagents of the live/deads

Baclight bacterial viability kit (L-7012, Molecular Probe Europe, Leiden, The Netherlands) were mixed thor-oughly. An aliquot of 3 mL/mL of this solution was added to the suspension of bacteria and small debris of cornified material. After incuba-tion at room temperature for 15 min, the material was submitted to dual flow cytometry.

Fluorescence data from both live (green fluor-escence) and dead (red fluorfluor-escence) bacteria were analyzed by a FACStar flow cell sorter coupled with the lysys II software for data ana-lysis (Becton-Dickinson, London, UK). Green TABLE 1. Eucerins ingredients Paraffinum liquidum Cera microcristallina Oenothera biennis Ceresin Zinc oxide Ceteareth 6

Hydrogenated castor oil Magnesium stearate Stearyl alcohol Cholesterol

Lanolin alcohol (Eucerit) Aluminum stearates Chamomilla recutita Ethoxydiglycol Propylene glycol BHT Aqua

fluorescence values measured at 530 nm were plotted against red fluorescence values measured at 620 nm. Data were analyzed for the percen-tages of live bacteria, dead bacteria and injured bacteria. The ratios of injured-to-live bacteria, and of dead-to-live bacteria were evaluated.

Missing evaluations were replaced using the ‘Last Observation Carried Forward’ (LOCF) method. The data distributions were skewed. Hence, the medians and percentiles 20 (P20) and 80 (P80) were determined. Proportions were calculated to describe the changes from baseline. For both test sites and each parameter, the differences between median values calculated at each cycle were tested for significance using the paired non-parametric Friedman and Dunn tests. At each evaluation time, the differences and the Wilcoxon-matched paired test were used to compare parameters between the two topically treated sites. All results were considered to be significant at the 5% critical level (Po0.05).

Results

At inclusion in the study, no difference was present in any of the evaluation parameters between the hemifaces ascribed for receiving the given products. All the 35 volunteers com-pleted the study, but a total of six visits were missing because the defined days of assessment was not respected by the volunteers. The toler-ance of both products was excellent with any sign of intolerance and any complaint of discomfort.

Some significant changes were yielded in time in the values of the evaluation parameters.

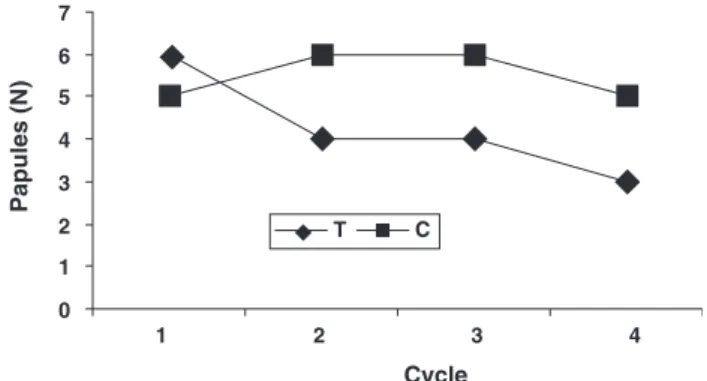

Compared with baseline, the number of pa-pules was already decreased after the first treat-ment cycle (Po0.05), and the improvetreat-ment was further increased (Po0.01) after the second and third cycles (Fig. 1). No significant changes were yielded at the control sites. The difference be-tween the two hemifaces reached significance (Po0.01) since the first treatment period.

Compared with baseline a*values, the erythe-ma was significantly decreased after one treat-ment period (Po0.01) and further on (Po0.001) (Fig. 2). No significant changes were present on the control hemiface. The reduction in the para-meter a* at the treated sites compared with the control site was highly significant (Po0.001) after each of the three treatment phases.

The Friedman test indicated a significant change in both the number (Po0.05) and cumulative

size (Po0.01) of follicular casts during treat-ment, but the Dunn post-test failed to identify a specific time of efficacy. No variations in time of these parameters were disclosed on the control site. The comparison between the two hemifaces indicated a significant decrease (Po0.01) in both the number and cumulative size of follicular casts beginning at the second treatment phase (Figs 3 a, b).

Compared with baseline values, the percentage of fluorescent follicular casts was significantly reduced after two (Po0.05) and three (Po0.001) treatment phases (Fig. 4). By contrast, the control area showed an increase in the percentage of fluorescent follicles between baseline and the second month (Po0.01), and between the first and the second month (Po0.05). The difference

between the two hemifaces was

signifi-cant (Po0.0001) beginning the second month of treatment.

Data on flow cytometry assessments are pre-sented in Table 2. The median value in the injured-to-live bacteria ratio reached 66% and

0 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 T C Papules (N) Cycle

Fig. 1. Median number (N) of acne papules on the hemifaces treated by the medicated paste (T) or receiving the non-medicated preparation (C). Intersite difference***Po0.01.

0 1 2 3 4 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 T C a* Cycle

Fig. 2. Erythema of the acne papules measured by the parameter a*on the hemifaces treated by the medicated paste (T) or receiving the non-medicated preparation (C). Intersite difference***Po0.001.

25% on the treated and control hemifaces, respec-tively. The median value in the dead-to-living bacteria ratio reached 84% and 14% on the trea-ted and control hemifaces, respectively. The

differences between each of these two assess-ments reached significance (Po0.01).

Discussion

Compliance is undoubtedly one important rea-son for treatment failures of acne. The presently tested formulations were well tolerated and the overnight applications did not interfere signifi-cantly with the individual life-styles of the pa-tients. Compliance was much better than that experienced with many other topical anti-acne therapies.

It is accepted that a placebo or vehicle effect in acne trials can be as high as 40% (20, 21). There is also a natural background variation in the ther-apeutic response of milder acne forms including catamenial acne. Psychological factors indepen-dent of other aggravating or precipitating factors are also operative in the disease evolution. In-deed, some improvement may occur in indivi-duals when they are seeking treatment, and when they expect to get better (20). Such a complexity in the acne process incited us to conduct an intra-individual comparison of two topical products using the split-face method. Thus we expected to minimize many of the intercurrent uncontrolled confounding factors.

Some reports (20) and our own experience suggest that the average duration of inflamma-tory papules in young women run over about 10 days. The severity of catamenial acne seems to peak in the very first days of the ovarian cycle in parallel with variation in the sebum excretion (22, 23). Hence, the trial planned a 1-week topical treatment followed by assessments early in the course of the ovarian cycle.

The medicated paste contained miconazole nitrate, which is a time-honored compound ac-tive against many fungi including Malassezia yeasts, and against many gram-positive bacteria including Staphylococcus spp. and P. acnes (24, 25).

0 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 T C Microcomedo (N/cm 2) Cycle 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2 1.4 1.6 T C

Microcomedo cumulative size

(mm 2/cm 2) Cycle a b

Fig. 3. Microcomedones on the hemifaces treated by the medicated paste (T) or receiving the non-medicated preparation (C). a, density; b, cumulative size. Intersite difference**Po0.01.

0 1 2 3 4 2 4 6 8 10 12 T C

Fluorescent follicular cast (%)

Cycle

Fig. 4. Percentage of fluorescent microcomedones on the hemifaces treated by the medicated paste (T) or receiving the non-medicated preparation (C). Intersite difference***Po0.001.

TABLE 2. Dual flow cytometry assessment of intrafollicular bacterial viability at completion of the study in the five most severely affected patients at inclusion

Patient

Injured/live bacteria (%) Dead/live bacteria (%)

Treated Control Treated Control

1 40.1/23.3 (172) 28.4/37 (77) 30.8/23.3 (132) 18.6/37 (50)

2 29.9/45.4 (66) 13.5/73.3 (18) 21.5/45.4 (47) 10.2/73.3 (14)

3 8.7/66.7 (13) 10.1/81.2 (12) 20.6/66.7 (31) 3.6/81.2 (4)

4 35.0/33.4 (165) 31.2/37.2 (84) 28.2/33.4 (84) 24.1/37.2 (65)

All these microorganisms may be involved in acne and acne-related disorders (2, 26, 27). The present study shows that the paste was signifi-cantly more effective in acne than the non-medi-cated cream. A similar paste formulation was previously tested with success in other inflam-matory dermatoses (28). In this study, the anti-inflammatory properties of the paste appeared to be one important facet involved in the rapid resolution of papular lesions. The seemingly comedolytic effect is more puzzling because no specific and direct effect can be expected in intercorneocyte binding from the components of the medicated paste. This is at variance with other products (16, 17). An indirect and yet undisclosed effect might be operative.

References

1. Toyoda M, Merohashi M. Pathogenesis of acne. Med Electron Microsc 2001; 24: 29–40.

2. Zouboulis CC. Is acne vulgaris a genuine inflammatory disease? Dermatology 2001; 203: 277–283.

3. Mulder MMS, Sigurdsson V, van Zuuren EJ et al. Psy-chosocial impact of acne vulgaris. Evaluation of the relation between a change in clinical acne severity and psychosocial state. Dermatology 2001; 203: 124–130. 4. Pie´rard-Franchimont C, Gaspard V, Lacante P et al. A

quantitative biometrological assessment of acne and hormonal evaluation in young women using a triphasic low-dose oral contraceptive containing gestodene. Eur J Contracep Reprod Health Care 2000; 5: 275–286. 5. Vartiainen M, de Gezelle H, Broekmeulen JH.

Compar-ison of the effect on acne with a combiphasic desoges-trel-containing oral contraceptive and a preparation containing cyproterone acetate. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2001; 6: 46–53.

6. Worret I, Arp W, Zahradnik HP, Andreas JO, Binder N. Acne resolution rates: results of a single-blind, rando-mized, controlled, parallel phase III trial with EE/CMA (Belaras

) and EE/LNG (Microgynons

). Dermatology 2001; 203: 38–44.

7. Jemec GBE, Linneberg A, Nielsen NH et al. Have oral contraceptives reduced the prevalence of acne? A popu-lation-based study of acne vulgaris, tobacco smok-ing and oral contraceptives. Dermatology 2002; 204: 179–184.

8. Pie´rard-franchimont C, Goffin V, Arrese JE et al. Lyme-cycline and minoLyme-cycline in inflammatory acne. A ran-domized, double-blind study on clinical and in vivo antibacterial efficacy. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 2002; 15: 112–119.

9. Kawada A, Aragane Y, Tezuka T. Levofloxacin is effec-tive for inflammatory acne and achieves high levels in the lesions: an open study. Dermatology 2002; 204: 301–302.

10. Eady EA. Bacterial resistance in acne. Dermatology 1998; 196: 59–66.

11. O’Brien SC, Lewis JB, Cunliffe WJ. The Leeds revised acne grading system. J Dermatol Treat 1998; 9: 215–220.

12. Barel AO, Clarys P, Alewaeters K et al. The Visi-Chroma VC-100s

: a new imaging colorimeter for dermatocos-metic research. Skin Res Technol 2001; 7: 24–31. 13. Mills OH Jr, Kligman AM. The follicular biopsy.

Derma-tologica 1983; 167: 57–63.

14. Pierard GE, Pie´rard-Franchimont C, Goffin V. Digital image analysis of microcomedones. Dermatology 1995; 190: 99–103.

15. Letawe C, Boone M, Pie´rard GE. Digital image analysis of the effect of topically applied linoleic acid on acne microcomedones. Clin Exp Dermatol 1998; 23: 56–58. 16. Pie´rard-Franchimont C, Henry F, Fraiture AL et al.

Split-face clinical and bio-instrumental comparison of 0.1% adapalene and 0.05% tretinoin in facial acne. Dermatol-ogy 1999; 198: 218–222.

17. Uhoda E, Pie´rard-Franchimont C, Pie´rard GE. Comedo-lysis by a lipohydroxyacid formulation in acne prone subjects. Eur J Dermatol 2003; 13: 65–68.

18. McGinley KJ, Webster GF, Leyden JJ. Facial follicular porphyrin fluorescence: correlation with age and den-sity of Propionibacterium acnes. Br J Dermatol 1980; 102: 437–441.

19. Sauermann G, Ebens B, Hoppe U. Analysis of facial comedos by porphyrin fluorescence and image analysis. J Toxicol-Cultan Ocul Toxicol 1990; 9: 369–385.

20. Shalita AR. Clinical aspects of acne. Dermatology 1998; 196: 93–94.

21. Dreno B, Moyse D, Alirezai M et al. Multicenter rando-mized comparative double-blind controlled clinical trial of the safety and efficacy of zinc gluconate vs. minocy-cline hydrochloride in the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris. Dermatology 2001; 203: 135–140.

22. Burton JL, Cartlidge M, Shuster S. Variations in sebum excretion during the menstrual cycle. Acta Derm Vener-eol 1973; 53: 81–84.

23. Pie´rard-Franchimont C, Pie´rard GE, Kligman A. Rhythm of sebum excretion during the menstrual cycle. Derma-tologica 1991; 182: 211–213.

24. Van Cutsem J, Thienpont D. Miconazole, a broad spectrum antimycotic agent with antibacterial activity. Chemotherapy 1972; 17: 392–404.

25. Degreef H, Vanden Bussche G. Double blind evaluation of a miconazole-benzoylperoxide combination for topi-cal treatment of acne vulgaris. Dermatologica 1982; 164: 201–208.

26. Back O, Faergemann J, Hornqvist R. Pityrosporum folli-culitis: a common disease of the young and middle-aged. J Am Acad Dermatol 1985; 12: 56–61.

27. Yu HJ, Lee SK, Son SJ et al. Steroid acne vs Pityrosporum folliculitis: the incidence of Pityrosporum ovale and the effect of antifungal drugs in steroid acne. Int J Dermatol 1998; 37: 772–777.

28. Pie´rard-Franchimont C, Letawe C, Pierard GE. Tribolo-gical and mycoloTribolo-gical consequences of the use of a miconazole nitrate-containing paste for the prevention of diaper dermatitis: an open pilot study. Eur J Ped 1996; 155: 756–758.

Address: Prof. GE Pie´rard

Department of Dermatopathology CHU Sart Tilman

B-4000 Lie`ge Belgium

Fax: 132 4 3662976