Parents’ Childhood Maltreatment and Subsequent

Parenting

Thèse

Laura-Émilie Savage

Doctorat en psychologie - recherche et intervention

Philosophiæ doctor (Ph. D.)

Parents’ Childhood Maltreatment and Subsequent

Parenting

Thèse

Laura-Émilie Savage

Sous la direction de :

Résumé

L’objectif principal de cette thèse est de documenter l’association entre les expériences de maltraitance vécues à l’enfance par les parents et leurs comportements parentaux subséquents et d’explorer les mécanismes et les variables sous-jacents à cette association.

D’abord, une méta-analyse des études qui ont examiné l’association entre la maltraitance vécue à l’enfance par les mères et leurs comportements parentaux subséquents à l’endroit de leurs enfants de 0 à 6 ans a été conduite. La possibilité que certaines variations méthodologiques et conceptuelles puissent agir comme modérateurs de cette association a aussi été testée. Au total, 32 études ont été retenues et les analyses ont révélé une association faible et significative entre le vécu de maltraitance à l’enfance et les comportements parentaux subséquents (r = –.13, p < .05). Les analyses de modération ont également révélé que l’association entre ces deux variables est de plus grande magnitude lorsque les comportements parentaux mesurés étaient des comportements négatifs, potentiellement abusifs, ou encore faisaient état de la qualité de la relation parent-enfant. L’association était également plus élevée dans les échantillons contenant une plus grande proportion de mères de garçons et lorsque les études étaient moins récentes.

Deuxièmement, une étude empirique a été conduite afin de répliquer les résultats impliquant une association entre l’exposition des mères à de la maltraitance à l’enfance et leur sensibilité maternelle ainsi que pour tester les mécanismes sous-jacents potentiels. Alors que des études ont démontré que certaines caractéristiques maternelles (i.e., adaptation psychosociale, représentation d’attachement) et environnementales (i.e., faible vs haut risque) pouvaient partiellement expliquer l’association entre l’historique de maltraitance et la sensibilité maternelle, aucune de ces études n’a testé toutes ces variables dans une même étude. C’est pourquoi cette étude visait à tester ces variables comme potentiels médiateurs et modérateurs de cette association ainsi que tester leur effet direct sur la sensibilité maternelle. Les résultats ont permis de répliquer l’association entre la maltraitance vécue à l’enfance et la sensibilité de mères envers leurs enfants de 18 mois. En plus de la maltraitance vécue à l’enfance, le risque et les représentations d’attachement étaient tous prédicteurs de la sensibilité maternelle. Toutefois, aucune médiation n’a été trouvée, suggérant que bien ce ces variables agissent simultanément sur la prédiction de la sensibilité maternelle, nous ne sommes toujours pas en mesure de documenter comment celles-ci interagissent ensemble. Les résultats ont aussi révélé que l’adaptation psychosociale agit comme un modérateur de l’association principale, celle-ci étant de plus grande magnitude pour les mères présentant moins de difficultés d’adaptation.

Abstract

The purpose of this research project is to document the association between parents’ experiences of childhood maltreatment (CM) and their subsequent parenting behaviors and to further our understanding of the processes and variables influencing this association.

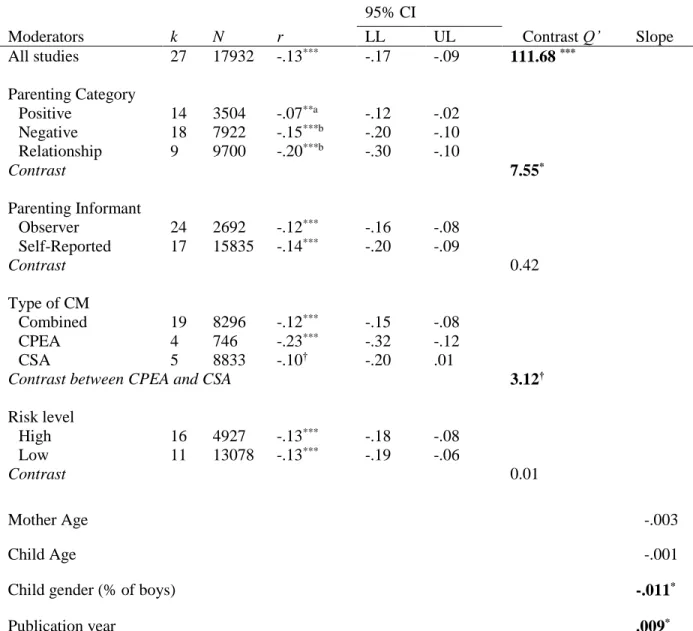

First, a meta-analysis of studies that have examined the association between mothers’ exposure to CM and their subsequent parenting behaviors towards their 0-6 years old children was conducted. The potential impact of both conceptual and methodological moderators has also been tested. A total of 32 studies were retained for analysis and results reveal a small but statistically significant association between maternal exposure to CM and parenting behavior (r = –.13, p < .05). Moderator analyses reveal that the association between CM and parenting are of greater magnitude when parenting measures involved relationship-based or negative, potentially abusive behaviors, when samples have greater proportions of boys compared to girls, and when studies were older versus more recent.

Second, an empirical study was conducted in order to replicate the findings suggesting an association between mothers’ exposure to CM and maternal sensitivity and to test its potential underlying mechanisms. While previous studies have suggested that maternal (i.e., psychosocial adjustment, attachment state of mind) and environmental (low- vs high-risk) characteristics partially explain the association between CM and parenting, none of these studies have considered all these variables together. This second study thus aimed to test the potential mediating or moderating effect of these variables on the association between CM and parenting outcomes as well as their direct effect on maternal sensitivity. Results replicated the association between CM and lower maternal sensitivity of mothers of 18-months-old children. Together with CM, risk and attachment state of mind were all predictive of maternal sensitivity. However, no mediation effect was found, suggesting that while all these variables act simultaneously, we remain uncertain as how they interact with each other. Results also revealed that psychosocial adjustment acts as a moderator of the association between CM and maternal sensitivity, the association being stronger for mothers presenting fewer adjustment difficulties.

Table of contents

Résumé ... ii

Abstract ... iii

Table of contents ... iv

List of tables and figures ... vii

List of abbreviations ... ix

Thanks ... x

Foreword ... xii

Introduction ... 1

Research Paradigm ... 4

CM: Definition and Prevalence ... 6

CM: Impact on Parenting ... 9

Attachment state of mind. ... 11

Psychosocial adjustment. ... 13

Accounting for the developmental ecology: an addition to the CM-parenting model ... 16

Methodological Considerations and Enduring Questions ... 17

Objectives and Hypothesis ... 19

Chapter 1. Maternal history of childhood maltreatment and later parenting behavior: A meta-analysis. ... 21 1.1 Résumé ... 21 1.2 Abstract ... 21 1.3 Introduction ... 24 1.4 Methods ... 30 1.5 Results ... 33 1.6 Discussion ... 34 1.7 References ... 38

Chapter 2. Risk Ecology and Exposure to Childhood Maltreatment ... 53 2.1 Résumé ... 53 2.2 Abstract ... 53 2.3 Introduction ... 55 2.4 Methods ... 56 2.5 Results ... 57 2.6 Discussion ... 58 2.7 References ... 60

Chapter 3. Childhood Maltreatment Experiences, Attachment State of Mind, and Psychosocial Risk as Predictors of Maternal Sensitivity ... 67

3.1 Résumé ... 67 3.2 Abstract ... 68 3.3 Introduction ... 69 3.4 Method ... 73 3.5 Results ... 78 3.6 Discussion ... 80 3.7 References ... 84 Conclusion... 98 Research objectives ... 98

Maternal history of childhood maltreatment and later parenting behavior: A meta-analysis. ... 98

Childhood maltreatment experiences, psychosocial risk, and attachment state of mind as predictors of maternal sensitivity ... 100

Dissertation Contributions... 101

Dissertation Limits ... 103

Future Directions ... 104

Annexe A. French Adaptation of the Maltreatment Classification Scale (Barnett, Cicchetti and Manly, 1993) ... 117

List of tables and figures

Tables presented in Chapter 1.

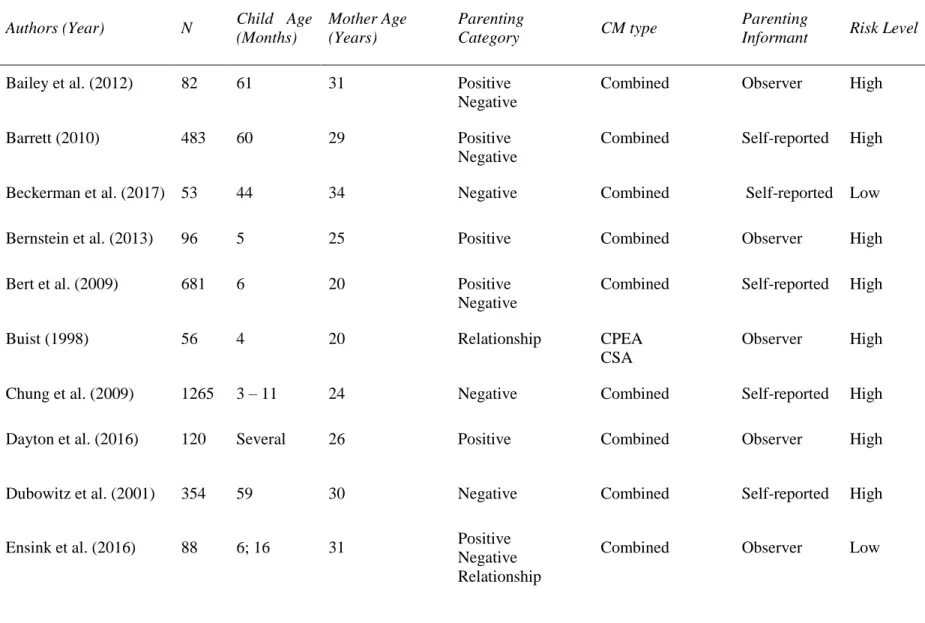

Table 1. Studies Included in Meta-Analysis ... 46

Table 2. Parenting Aspects/Behaviors in Function of their Category of Belonging ... 49

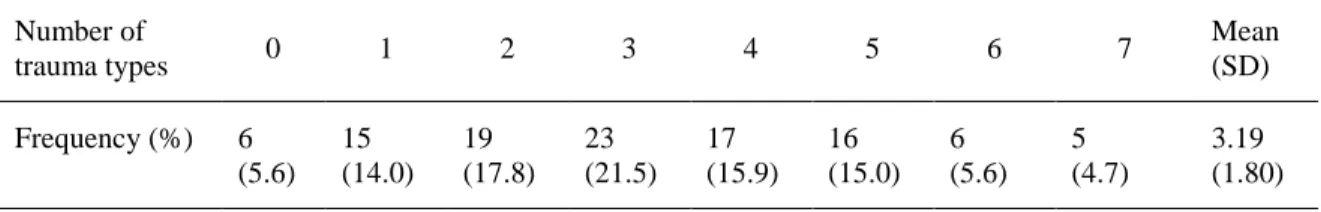

Table 3. Association Between CM and Parenting for All Studies and as a Function of Moderators 51 Tables presented in Chapter 2. Table 1. Number of Childhood Maltreatment Types Experienced for All Mothers ... 62

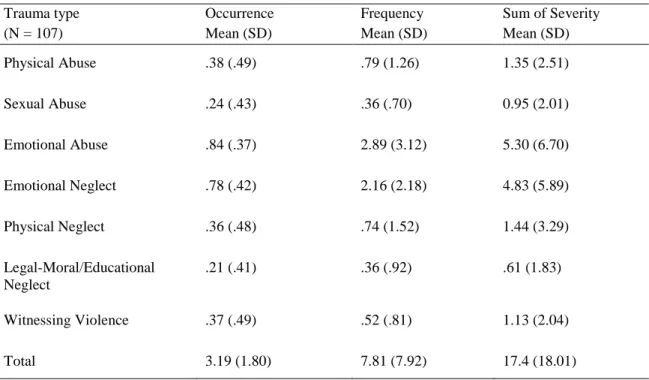

Table 2. Occurrence, Frequency and Sum of Severity of Each CM Type Among All Mothers ... 63

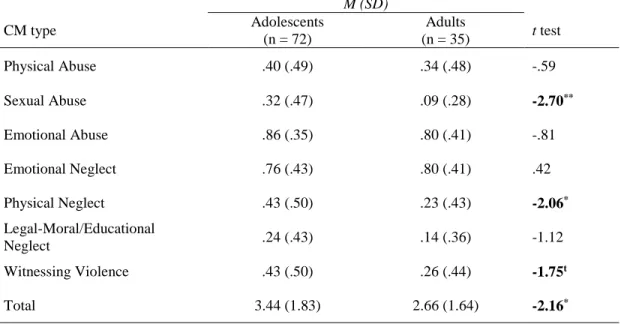

Table 3. Mean and Standard Deviation of Each Type of CM Occurrence by Group ... 64

Table 4. Mean and Standard Deviation of Each Type of CM Frequency by Group. ... 65

Table 5. Mean and Standard Deviation of Each Type of CM Sum of Severity by Group. ... 66

Tables presented in Chapter 3.

Table 1. AAI Three-Way Classification as a Function of Risk Status ... 92Table 2. Exploratory Factor Analysis Results for the MCS Sum of Severity Subscales ... 93

Table 3. Means, Standard Deviations and Bivariate Correlations among Study Variables ... 94

Table 4. Summary of Regression Analyses Predicting Maternal Sensitivity with the Abuse and Neglect Variables ... 95

Figures presented in Chapter 1.

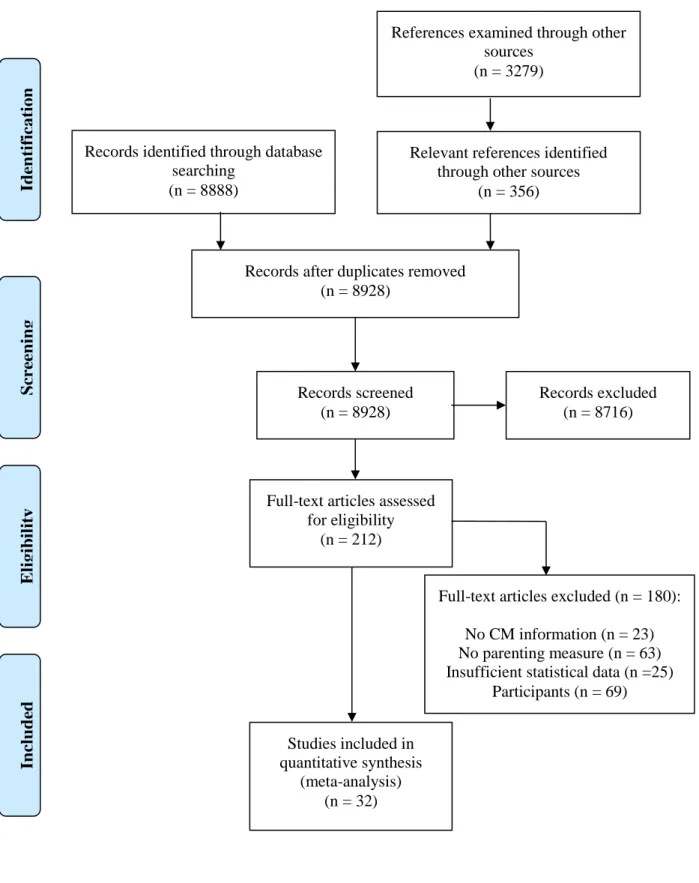

Figure 1. Flow Diagram for Selection of Articles ... 45 Figure 2. Forest Plot of Included Studies ... 50

Figures presented in Chapter 3.

Figure 1. Scatter plot of Maternal Sensitivity by Abuse as a Function of the Depressive Symptoms Level (with risk and coherence of mind as covariates) ... 96 Figure 2. Scatter plot of Maternal Sensitivity by Neglect as a function of the Depressive Symptoms Level (with risk and coherence of mind as covariates) ... 97

List of abbreviations

AAI: Adult Attachment Interview CI: Confidence IntervalCM: Childhood Maltreatment COM: Coherence of Mind

CPEA: Childhood Physicial and/or Emotional Abuse CSA: Childhood Sexual Abuse

MBQS: Maternal Behavior Q-Sort

NDACAN: National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect NCTSN: National Child Traumatic Stress Network

Thanks

Le dépôt de cette thèse annonce la fin d’un parcours parsemé de petits et de grands apprentissages. Bien qu’il s’agisse d’une tâche académique, sa réalisation n’aurait été possible sans l’humanité des mentors, proches et amis qui m’ont épaulée et soutenue dans cette aventure des cinq dernières années, que je tiens à remercier. Tout d’abord, un grand merci à mon directeur de thèse et mentor, M. George Tarabulsy, qui a vu en moi un potentiel que je ne me connaissais pas et qui m’a donné tant d’opportunités de me développer sur les plans académique, scientifique et humain. George, ta volonté à non seulement mener des études auprès de populations vulnérables malgré les défis que cela comporte, mais aussi de te mobiliser pour t’assurer que ces gens puissent bénéficier de cette recherche me sera toujours un guide professionnel et éthique. Merci pour ta grande générosité, pour ton dévouement et pour les nombreux souvenirs de congrès et de formation qui ont agrémenté de rires et d’intéressantes discussions mon parcours au doctorat.

Merci également aux membres de mon comité de thèse, Mmes Célia Matte-Gagné et Delphine Collin-Vézina. Vos conseils m’ont permis de me dépasser et de considérer tous les aspects de la recherche, passant des statistiques aux humains qui se cachent derrière ces chiffres. Merci à M. Stéphane Sabourin et Mme Andrea Gonzalez d’avoir accepté de faire partie de mon jury de thèse et d’ainsi m’accompagner vers l’accomplissement et l’achèvement de ce parcours.

Je souhaite également remercier mes mentors cliniques qui m’ont permis, chacun à leur façon, de faire le pont entre les connaissances théoriques acquises au cours de mon doctorat et leur application pratique, et vice-versa. Mme Normandin, merci d’avoir sollicité mes connaissances théoriques à l’application pratique de la thérapie et de m’avoir montré qu’on doit avoir confiance en ses moyens pour être en mesure d’aider réellement. M. Sabourin, merci pour votre bienveillance et pour votre accompagnement rigoureux et passionné au cours des trois dernières années. Tel un sage superviseur, vous m’avez permis de m’approcher de la thérapeute que je peux être en respectant mon style, mon bagage théorique et mes préférences. Votre disponibilité et votre générosité m’ont permis non seulement d’avoir accès à vos réflexions et compétences, mais aussi de m’approprier les miennes en tant que thérapeute. Mme Lefebvre, merci de votre pédagogie accélérée et de vos encouragements récurrents. Vous m’avez appris que le regard que l’on porte sur les gens a le pouvoir de les faire se sentir vivants, intéressants et importants. Marie-Hélène, merci de toute la confiance que tu me voues et de l’impressionnante humilité que tu m’enseignes au quotidien, tout ça enrobé de muffins et de chocolats. Merci d’incarner aussi vigoureusement les convictions qui te mènent à vouloir travailler auprès des enfants et adolescents en difficulté, te faisant ainsi une gardienne de notre société. Marie-Soleil, merci de ta passion et de ta curiosité contagieuses pour la psychologie. Ton éthique rigoureuse

dans l’application des meilleures pratiques auprès des gens que nous soignons rend bien vivante l’une des principales vocations de la recherche, soit celle d’aider le mieux possible.

Merci aussi aux ami(e)s du labo et du doctorat pour les moments partagés, les discussions, les galettes et le plaisir, tous nécessaires à la vie doctorale. Un merci spécial aussi à Claire et Jessica. Je me sens très privilégiée d’avoir pu compter sur vous comme sur des mentors, mais également pour l’amitié qu’on a pu développer au fil des ans. Je n’ai aucune idée de comment j’aurais pu traverser ce parcours sans vous, votre précieux support, nos nombreux fous rires et nos dîners au Matto. Merci aussi de m’avoir impliquée de diverses manières dans vos projets, votre confiance à mon endroit me touche énormément.

Enfin, merci à ceux qui, en dehors de la sphère académique, m’ont été d’un support inébranlable au fil des ans. P’pa, M’man, Alexe, vous êtes le meilleur fan club que j’aurais pu espérer! Merci de vos encouragements, de vos visites, de votre accueil toujours chaleureux et de votre fierté à mon endroit. Vous êtes pour moi le point de départ de toutes les expériences et réussites de ma vie car j’ai la certitude que je pourrai toujours compter sur vous. Myriam, merci de ton amour, de ta patience, de ta bienveillance et d’avoir été compréhensive du mode de vie qu’implique la réalisation d’un doctorat. Merci de m’avoir permis un certain équilibre entre la vie et les études et d’avoir toujours veillé à mettre du plaisir dans notre quotidien. Merci de t’être intéressée à mes travaux et à mon bien-être au fil des ans et d’avoir ramé parfois pour deux pour qu’on se retrouve dans tout cela. Mon parcours n’aurait pas été le même sans ta présence réconfortante à mes côtés.

Foreword

The first paper included in the present dissertation, entitled « Maternal history of childhood

maltreatment and later parenting behavior: A meta-analysis » was published in Development and Psychopathology on February 13th 2019. The author of this paper and dissertation was primarily

responsible for all aspects of this study (i.e., systematic review, data extraction, analyses, interpretation of results and writing). The contribution of the co-authors go as follows:

George M. Tarabulsy, Ph.D., Associate Professor at Laval University and Director of the University Centre for Research on Youth and Family: Thesis director, supervised and guided every step of the study, helped code papers and collaborated in the analyses, interpretation and the writing of the report. Jessica Pearson, Ph.D., University of Québec at Trois-Rivières Professor: Helped elaborate the data extraction grid, took part in the analyses and interpretation process and reviewed different versions of the manuscript.

Delphine Collin-Vézina, Ph.D., Associate Professor at McGill University and Director of the Centre for Research on Children and Families: Helped with conceptual and theoretical issues at the core of the study and reviewed different versions of the manuscript.

Lisa-Marie Gagné, B.A.: Helped with the coding of studies, the elaboration of coding criteria and reviewed different versions of the manuscript.

Introduction

Many studies have shown that maternal experiences of child maltreatment (CM; including exposure to physical, psychological and sexual abuse, psychological and physical neglect that occurred before age 18) may be linked to child socioemotional development (Briggs et al., 2014; Lyons-Ruth & Block, 1996). Children of mothers exposed to CM are at greater risk of developing problems such as impulsivity, aggressiveness, reactivity to novelty, depression and anxiety and to develop disorganized attachment with their caregiver (Madigan, Moran, & Pederson, 2006; Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, & Jenkins, 2015).

Ainsworth and others working from an attachment paradigm (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005) have long postulated that child socioemotional development is associated with the attachment relationships they form with their parents and that the quality of these relationships highly depends on the parenting they receive in the context of daily interactions (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Bowlby, 1982; De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997; Verhage et al., 2018). The attachment the child forms with his or her parents functions as a blueprint for other social interactions and relationships, and indeed, much of the early work on validating the attachment paradigm came in the form of predictions, based on early attachment, of different aspects of social functioning (for a review, see Pallini, Baiocco, Schneider, Madigan, & Atkinson, 2014). It is pertinent to note, in this empirical context, that maltreated children are more likely to form insecure or disorganized attachment relationships with their parents (Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, 2010). Also, parents that are assessed as being insecure or unresolved with regard to loss or trauma more frequently engage in less sensitive and sometimes potentially abusive interactions with their offspring, which often leads to other insecure or disorganized relationships (Madigan et al., 2007; Reijman et al., 2017).

In addition to the attachment paradigm, the more general developmental psychopathology framework, which implies that an individual’s psychological adjustment can be hindered by early experiences of adversity with long term developmental consequences, suggests another complementary path through which CM may affect later parenting. Here, experiences of CM can impinge on multiple spheres human development that may also impact parenting. For example, victims of CM tend to show more frequent difficulties in individual adjustment and more often report higher levels of anxiety, depression, hostile behaviors and high levels of stress (Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, et al., 2014), all of which have been linked to difficulties in mother-infant interactions and parenting (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000). Whether it be from an attachment or a developmental perspective, much of the research suggests that when CM victims become parents, there is a greater likelihood that parent-child

interactions may be problematic and less conducive to positive child development (Madigan et al., 2019; Savage, Tarabulsy, Pearson, Collin-Vezina, & Gagne, 2019). As such, the effects of CM may be passed on to the next generation (Tarabulsy, Moran, Pederson, Provost, & Larose, 2011). Indeed, the possibility that CM victims transmit the consequences of their experiences of CM through parenting has been suggested in a broad array of research (for reviews, see Madigan et al., 2019; Savage et al., 2019). Yet, it is not all women that experienced CM that go on to become insensitive mothers. Although there is a statistical tendency suggesting a relation between CM experiences and later parenting behaviors that emerges from the data, CM is not deterministic. Many women with experiences of CM become sensitive mothers despite their past, suggesting that the association between CM and parenting is complex and that other factors may influence the transmission of the consequences of CM onto the next generation.

In fact, the results of studies that have examined the transmission hypothesis have not always yielded consistent results. The proposed links between constructs have sometimes been difficult to document. For example, in a study of the association between CM and later adjustment difficulties, Jansen and colleagues (2016) found no relation between sexual abuse and maternal depression. Madigan and her colleagues (2014) found no relationship between a history physical abuse and symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents transitioning to motherhood. Others found no link between maternal interactive sensitivity and prior experiences of physical and/or sexual abuse (Bailey, DeOliveira, Wolfe, Evans, & Hartwick, 2012; Fitzgerald, Shipman, Jackson, McMahon, & Hanley, 2005) or emotional abuse and physical and/or emotional neglect (Dayton, Huth-Bocks, & Busuito, 2016). Thus, while there is general support for the basic hypothesis that CM leads to different types of problematic parenting, results that do not support this hypothesis are also regularly found and require attention.

Such discrepancies may be attributable to variations in the methodologies used to address this issue. For example, some authors operationalize CM based on the presence or absence of any such experience, with no consideration for the severity or frequency of the CM experiences. Others have not explored the potential differences in the impacts related to different types of CM. Moreover, measurement issues and the operationalization of different variables may also affect findings in this type of research. For example, some have focussed on negative parenting behaviors (e.g., abusive behaviors), while others documented more normative indices of parenting behaviors such as maternal sensitivity during infancy. These different parenting concepts may be measured via observations in laboratory or home settings, with different types of procedures, or, alternatively, by way of self-reports. These types of variations in assessment may induce differences in the operationalization of the construct that is analysed. Finally, part of the discrepancies can arise from differences in the ecological context in which the studies take place. Indeed, the majority of studies have focused mainly on the direct relation between variables, such as the link between CM and their

outcomes or problems in attachment state of mind, adjustment and sensitivity, with little or no attention to the context in which they took place. It is possible that certain critical or otherwise confounding variables may have been missed in different analyses and may have a bearing on the relations between variables. In this perspective, these missing environmental variables may be viewed as being part of the developmental processes involved in testing the role of CM in parenting. Examples of such factors include maternal age and education, past attachment experiences and state of mind, as well as marital and partner presence, support and adjustment.

Researchers who have addressed the relation between CM and parenting have proposed two major hypotheses to explain the relations between variables: First, some consider CM as a traumatic event that instigates a cascade of subsequent problems in terms of attachment state of mind (e.g., Huth-Bocks, Muzik, Beeghly, Earls, & Stacks, 2014; Reijman et al., 2017) or psychosocial adjustment (e.g., Ehrensaft, Knous-Westfall, Cohen, & Chen, 2015; Pereira et al., 2012). In this perspective, CM has its impacts on parenting through a process involving maternal attachment state of mind or adjustment difficulties. Thus, the link between maternal CM and parenting is mediated principally by maternal characteristics such as attachment state of mind and psychosocial adjustment. Second, some have hypothesized that the experience of CM is more likely in certain high-risk environments and, as such, are part of many kinds of experiences that may challenge early attachment relationships as well as affect maternal adjustment, and in turn mother-infant interactions (e.g., Stack et al., 2012). In this perspective, it is perhaps CM that mediates the relation between the quality of the home environment and parenting. Attachment state of mind and adjustment are also, in this perspective, a mediator of this basic association. This hypothesis places a greater emphasis on the potential toxic effects of some forms of home environments that favour the incidence of CM. In this particular hypothesis, subsequent difficulties in attachment state of mind, maternal adjustment and parenting may be directly linked to these difficult environments, reducing their potential meditational impact (Tarabulsy et al., 2005). Both basic hypotheses find some level of support in the literature.

The purpose of this study is to examine the processes by which CM may lead to problematic parenting while considering both methodological issues and environmental variables. Specifically, this project will examine the potential relation of CM to maternal interactive sensitivity and maternal attachment state of mind and adjustment in a high-risk sample of adolescent mother-infant dyads. By considering the ecology within which CM occurs, potentially linked to parenting outcome and somewhat confounding the direct link between CM and outcome, this study will enable us to examine the two major hypotheses that have attempted to account for this relation, as well as the potential discrepancies in results that have been observed. Although different elements of these two hypotheses have been empirically supported, there has not been a systematic effort to distinguish whether one accounts for the data better than the other. Part of

the goal of this research project is to understand the processes involved in the relationship between CM and parenting behaviors, considering elements related to the mother (i.e., attachment state of mind and adjustment) as well as to characteristics of the family ecology.

Two studies are proposed as part of this dissertation project. First, a meta-analysis on the relationship between maternal CM and parenting, with consideration for methodological and environmental aspects as potential moderators was conducted. Second, the relation between CM and maternal characteristics will be tested in an empirical study among mothers from low- and high-risk environments. Maternal psychosocial adjustment will be tested as potential mediator of this association. In both studies, the relative contributions of the CM and the environment will be verified.

This dissertation proposal is divided into six sections: First, the research paradigm in which this research is carried out is defined. Second, a broad definition of CM is given. This definitional exercise is important to the degree that different definitions have been considered as maltreatment and it is necessary to stipulate how this issue will be presently defined. Third, a description of the association between CM and maternal interactive sensitivity and potential mediating variables (i.e., psychosocial adjustment and attachment state of mind) is provided. Fourth, the role of the family ecology will be discussed and possible processes by which CM may affect parenting behaviors will be explored. Fifth, some of the enduring methodological issues that have affected our understanding of how CM may affect parenting will be addressed. Sixth, the objectives and hypothesis that will be used to accomplish the meta-analysis and the empirical study will be described.

Research Paradigm

What should be considered as childhood maltreatment or psychosocial risk? According to who? Why? As suggested by the dissertation committee, it is of particular importance to define the epistemological paradigm within which this research is embedded. When studying sensitive matters such as the long-term impacts of childhood maltreatment and psychosocial risk, it becomes crucial to define and articulate, as much as is possible, beliefs about the structure of reality and how it can be known and appropriated. In response to this request, this section aims to define the philosophical stance on which this project is based, and to disclaim some of the consequences of such positioning.

This research project is grounded in the postpositivist paradigm. In summary, postpositivists believe in the existence of only one, objective truth, which can however only be known imperfectly and probabilistically. They argue that the theories, background, knowledge and values of the researcher may

influence what is observed, leading to unavoidable biases. Postpositivists pursue objectivity by recognizing the possible effects of biases (Ryan, 2006).

The notion of bias is important in the context of the present research, examining variables such as childhood maltreatment, social risk, and maternal sensitivity. For example, what can be seen as parental educational practices in some cultures, such as spanking, can also be defined as abusive practices in others. Postpositivists do not intend to adopt a relativist point of view, questioning every position. Rather, they accept that there are biases and that some decisions are made in the process, influencing interpretation and perceptions of research results, and always acknowledging their potential impact on the understanding of concepts. In order to account for these possible biases, postpositivists are thus cautious in their interpretation of their results.

Guided by postpositivism, this dissertation addresses sensitive questions such as « Are experiences of CM related to later parenting behaviors »? In order to answer this question, decisions concerning the definition of childhood maltreatment as well as optimal parenting behavior have been taken. For example, the definition of CM has been guided by empirical evidence that some parental behaviors can be detrimental to further child development (what is detrimental also being subject to postpositive interpretation). But, although many parental behaviors have been examined, it is evident that many more have not received much attention, sometimes just because they are not socially believed to be harmful to child development. In other words, we pay attention to what our values and experiences lead us to believe might be harmful, which in turn implies a bias as we can only confirm or infirm what we considered important and thus measured in the first place. While we may not be able to completely uncover the mechanisms underneath many of the multifaceted questions that arise in a such complex field of research that is human development, we believe that research efforts are still helpful to uncover parts of that truth that are accessible to our means of investigation.

In considering the complexity of human experience, the imperfections of research methodology and the biases that we bring to the questions we study, it is expected that the results of our scientific quest be interpreted with consideration of these complexities and flaws. More specifically, how can we interpret the answers that arise from the present research? If indeed maternal CM experiences were associated to later parenting, would it mean that every mother that experienced CM would exhibit insensitive parenting? Obviously not. Rather, this finding would indicate that statistically, the fact that a mother experienced CM could put her at greater risk to interact less sensitively towards her children, insofar as our measures are valid indicators of the phenomena we have examined. On a clinical level, such an association may inform clinicians, orient their interventions in order to prevent such transmission of risk or help break the cycle in families that are perpetuating these behaviors. Yet, the research paradigm and the methodology, the latter

being described in a further section, are not helpful in the inference of causal relationships where one is « known » to cause the other. Rather, we here talk about statistical probabilities that CM can influence later parenting, but that many more factors may also be involved in predicting parenting. That CM may be seen as a risk factor does not preclude that it is an uncertain predictor of future maternal behaviour. In sum, it is important to acknowledge that in identifying the domain of study, the research design and in choosing the specific measures and analytic techniques, different biases have been at play. Some are known and some are not. To the degree that the author of this dissertation is aware of some, and to the degree that the reader is aware of the same strengths and limitations of the present research, the purpose of the dissertation is seen as both scientifically and clinically pertinent.

CM: Definition and Prevalence

Research on the intergenerational effects of the exposure to childhood maltreatment has grown exponentially over the last decades. Since there are great variations in what can be defined as maltreatment, a broad definition of what is meant by CM in the present research project is provided.

Experiences of CM are often referred to as childhood relational traumas. In order to grasp the impact of such experiences, it appears pertinent to first define and document the effects of childhood trauma in general, and second, to describe it in a relationship context. Childhood trauma can be defined as an individual under the age of 18 years witnessing or experiencing an event that poses a real or perceived threat to their life or well-being, thus overwhelming their ability to cope and causing feelings of fear, horror, or helplessness (National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2013). Since childhood is characterized by fundamental developmental processes, including the rapid growth of many areas of the brain (Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, 2009), as well as the formation of internal working models of social interactions (Bowlby, 1969; Koren-Karie, Oppenheim, & Getzler-Yosef, 2008), trauma that takes place during childhood may have a lasting impact on development by affecting such aspects of developmental process (Kliethermes, Schacht, & Drewry, 2014; World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). Among the broad range of events that can be traumatic for children (e.g., exposure to natural disasters, motor vehicle accidents, painful medical treatments, acts or threats of terrorism, abuse, neglect, etc.), traumatic events that occur within the context of a relationship (i.e., abuse and neglect) have been found to be the most detrimental (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2012), and to be more strongly related to the transmission of trauma-related symptomatology to the next generation than non-relationship-based trauma (Lambert, Holzer, & Hasbun, 2014).

Whether it involves neglect or abuse, CM is viewed as causing a break in a relational context; where a vulnerable child depends on someone who does not respond to their needs (i.e., neglect), is

malevolent (i.e., abuse) or both. The harm caused to the child is viewed as part of the loss of protection, the exposure to danger and often the loss of relationship with an attachment figure (Alexander, 2013). Although they can be perpetrated by other figures than the primary caregivers (e.g., relatives, household members, or people who provide temporary care or supervision such as day care providers, teachers, coaches), recent data show that in the United States, 91.4% of all victims of CM were abused or neglected by one or both of their parents (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015), supporting the often reported finding that most forms of CM takes place in the home and involve individuals who have a relationship with the child (Harden, Buhler, & Parra, 2016). The following are definitions of specific forms of CM:

Physical abuse. Physical abuse refers to violent physical acts directed towards a child. Physical

abuse can result in different levels of tissue injury, ranging from bruises and skin lacerations to broken bones or teeth. In extreme cases, physical abuse can lead to death (Briere & Jordan, 2009).

Sexual abuse. Sexual abuse is defined as any sexual contact directed against a child for the sexual

gratification of the offender, when the offender is in an age-related power imbalance (Briere & Jordan, 2009). In rare cases the offender is unknown. Most of the time and especially when directed towards younger children, sexual abuse is perpetrated by an attachment figure or another caregiver (Kaehler, Babcock, DePrince, & Freyd, 2013).

Emotional abuse. Emotional or psychological abuse is defined as a repeated pattern of

non-physical, harmful interactions with the child leading to feelings of worthlessness, of being unloved, unwanted and endangered on the part of the child (Glaser, 2011). Psychological abuse can take different forms such as criticism, rejection, devaluation or humiliation (Briere & Jordan, 2009). Parental behaviors such as spurning, terrorizing, isolating or exploiting/corrupting the child are also said to be abusive (American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children, 1995). A growing body of literature suggests that psychological abuse underlies other forms of maltreatment (Hart & Glaser, 2011).

Emotional neglect. Emotional or psychological neglect refers to the failure of the caregivers to

provide significant and sensitive caring, support and emotional stimulation to the child (Briere & Jordan, 2009). Here, we perceive the child as building representations of themselves and the world in a context where caregiver responses to child needs, emotions and signals are highly problematic and send the message that the child is perhaps a nuisance or that the caregiver is indifferent to the presence of the child.

Physical neglect. Physical neglect corresponds to the incapacity of the caregivers to provide

necessities such as food, clothing and shelter, as well as safety, supervision and physical (e.g., medical, dental) cares (NCTSN, 2015). While abuse is seen in the commission of behaviors, neglect is more about

the omission of behaviors necessary to the child’s wellbeing. Developmentally, lack of care has often been viewed as potentially harmful as other forms of abuse (Friedman & Billick, 2015).

Moral/Legal or Educational Maltreatment. Moral/legal or educational maltreatment refers to

parental behaviors or omissions that may undermine the child’s adequate socialization. The caregiver either exposes or involves the child in illegal activities, which may contribute to foster delinquency or antisocial behaviors. The failure of the parent to ensure that the child receives proper education is also included in this category, considering that failing to send the child to school might contribute to missocialization and hinder the child’s integration into the society’s expectations (Barnett, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1993).

Witnessing Violence. Witnessing violence refers to the child’s exposure to a caregiver’s acts or

threats of psychological or physical violence towards someone else (e.g., other parent, adult, other child). Such parental behavior is seen as an indicator of the parental lack of consideration for the child’s emotional well-being and security (Statistics Canada, 2017).

Depending on the specific events that are involved, most definitions of CM implicate repeated events rather than acute occurrences of single events, limited in time. Long-term events have sometimes been labeled as “complex trauma” (NCTSN, 2013). This finding is coherent with the idea that the perpetrator is usually part of the family ecology. Indeed, the presence of a threat in the proximal ecology can lead the child to experience a kind of perpetual trauma, not necessarily because of perpetrated maltreatment, but because the threat is ever present (Alexander, 2013). Similarly, although it is possible for a child to be exposed to a single kind of CM, most often these difficulties are related and co-occur and their effects are often heightened by their occurrence (Harden et al., 2016). Furthermore, many studies have found CM to be a risk factor for further exposure to multiple traumatic events (Brown, 2009; Chapman et al., 2004; Lanktree & Briere, 2013). As a result of this co-occurrence of different forms of trauma, CM tend to interfere with developmental process, often leading to long-lasting behavioral and emotional dysregulation (Milot, St-Laurent, & Éthier, 2016).

The context in which children develop seems to be particularly important in the understanding of the impact of CM on an individual. First, children growing up in high-risk family ecologies (e.g., poverty) are more susceptible to be exposed to traumatic experiences than their low-risk counterparts (Enlow, Blood, & Egeland, 2013). Second, not only does the risk in the environment increase the likelihood that a child will be exposed to CM, it also exacerbates the effects of such exposure on the child. Often, such environments involve younger parents who more frequently experience adjustment difficulties and possess fewer resources to help children cope with such events (Harden et al., 2016). Thus, the environments that

provide the context for CM, and which may serve to increase the possibility of their occurrence, also may in and of themselves have a negative impact on child outcome, whether or not CM has taken place, and may serve to exacerbate its impact if CM does occur. This inter-relation between CM and the family ecology has rarely been considered. In light of the important correlation between environment and CM, it is necessary to consider the environment in which CM occurs to understand their relative contributions to both parental and child outcome.

Prevalence. According to the WHO (2016), a quarter of all adults report having been physically

abused as children, and every one in five women report having been sexually abused as a child. In Canada, a community health survey performed in 2012 (Statistics Canada, 2013) revealed a similar portrait. Consistent with these data, one in five women experienced child physical abuse, and almost one in six women experienced sexual abuse (Afifi et al., 2014). In addition, more than three out of four victims of abuse have also experienced emotional or physical neglect (U.S. Department of Health Human Services, 2015). Correspondingly, a meta-analysis conducted by Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van Ijzendoorn (2013) revealed emotional neglect, followed by physical neglect, to be the most common forms of maltreatment.

Since CM are so highly prevalent and are associated to serious negative psychosocial adjustment across the lifespan of the victims (Milot et al., 2016) and their children (NCTSN, 2015), it is important to speculate as to the developmental processes that may serve to communicate parental experiences to child outcome.

CM: Impact on Parenting

One of the main hypotheses to explain the link between maternal CM and child outcome involves

the potential impacts on the mother and the possibility that this impact may serve as a mediator. The basic hypothesis is that CM affects the way mothers interact with their children, which is related to child outcome, by way of its first impact on maternal attachment states of mind and maternal adjustment. This model has certainly been suggested within the context of attachment research (e.g., Madigan et al., 2006) but it has also been proposed by other researchers whose work involves other aspects of developmental psychopathology (Babcock Fenerci, Chu, & DePrince, 2016; Martinez-Torteya et al., 2014)

A growing body of literature explores the potential effects of CM on parenting in general and maternal interactive sensitivity in particular (Bert, Guner, & Lanzi, 2009; Dilillo & Damashek, 2003; Fuchs et al., 2015; Pereira et al., 2012). However, the results vary greatly between studies. Some studies report a strong relationship between CM and maternal sensitivity. Among them, Fuchs and colleagues (2015)

examined the potential impact of maternal history of abuse on maternal sensitivity by observing mother-child interactions when mother-children were 12 months old in a low-risk sample. The sample was divided in two groups: one group including mothers with a self-reported history of childhood physical or sexual abuse (n = 58; maltreatment group), and one control group, including women who matched the characteristics of the mothers in the maltreatment group but who reported no such experiences (n = 61; control group). When compared, mothers from the control group were significantly more sensitive to their children than those from the maltreatment group during the 20 minutes free-play interaction.

Although of smaller magnitude, Bert and colleagues (2009) also found an association between CM and maternal sensitivity. In order to assess maternal sensitivity, they asked 681 mothers to complete self-reported questionnaires at 6 months postpartum. Correlation analyses revealed that exposure to both childhood emotional and physical abuse was associated with self-reports of parental behavior. These findings support the idea that maternal childhood adversity may impact future parenting behavior.

Conversely, some authors find no relationship between CM and maternal sensitivity. For example, Bailey and colleagues (2012) examined this relationship in a sample of 82 dyads of mothers with their 4- to 6-year-olds from a moderate-risk sample. Results showed no association between maternal CM and observed maternal interactive sensitivity. However, a history of sexual abuse was associated to maternal self-reports of parenting. Self-reported parenting outcomes and observed parenting behavior were unrelated, underlining the importance to have both sources of assessments when addressing the issue of parenting behavior.

These contradictory results and the difficulty that researchers have had in replicating results of the same magnitude between studies suggest that differences in methodology (i.e. type of CM measured; assessment of maternal sensitivity; timing) may be at stake. In addition, even within studies, sensitivity scores vary greatly. Indeed, not all mothers with CM show reduced maternal sensitivity, with some mothers being capable of high levels of sensitivity despite their history of CM. This heterogeneity within groups can lead to reduced statistical power and a lower probability to find significant differences in sensitivity between groups.

In an effort to make the model more complete and to account for a greater proportion of maternal experiences following CM, and to more accurately relate these experiences to maternal sensitivity, three predictors have been taken into account: 1) Attachment state of mind; 2) Psychosocial Adjustment; 3) Family Ecology.

Attachment state of mind. The Adult Attachment Interview (AAI; George, Kaplan, & Main, 1985)

is the most validated method of assessing individuals’ attachment state of mind (or attachment representations). The AAI is an hour-long, semi-structured interview during which individuals are asked to describe their childhood relationships with their attachment figures. From this interview, coders focus on the coherence of the discourse (Main & Goldwyn, 1998), which is thought to reflect individuals’ attachment state of mind, to first assign each participant to one of the three mutually exclusive categories: autonomous (secure); dismissing (insecure) or preoccupied (insecure). Secure individuals (Autonomous) tend to value relationships, and to acknowledge their influence in their lives. Their discourse about these relationships are coherent and consistent in nature. Conversely, insecure individuals tend to minimize the importance of relationships and their impacts on them and to talk about them in an overly defensive manner (Dismissing) or to remain caught up in their relationships with their parents, expressing anger or preoccupation in their discourse (Preoccupied). In addition to these three classifications, individuals that appear to become disoriented or psychologically confused when discussing experiences of loss or CM are classified as having an unresolved state of mind.

CM and attachment state of mind. Bowlby (1969, 1980) suggested that interaction patterns with

parents since early infancy lead to the construction of « internal working models » of self and others from which the individual then interprets and experiences other attachment relationships. In the case of abuse or neglect, these internal working models are typically negative. For example, maltreated children often conclude that they must be deserving of such treatment, are intrinsically unacceptable, and come to believe they are helpless, unlovable, weak, and to see others as dangerous, malevolent, rejecting or unavailable (Godbout, Briere, Sabourin, & Lussier, 2014). As a result, exposure to childhood maltreatment places individuals at high risk of developing unresolved or insecure states of mind of attachment, as measured by the AAI. Indeed, the association between CM and insecure or unresolved attachment has received much empirical support in abused or neglected children (Muller, Thornback, & Bedi, 2012), and in adults with CM histories (Bailey, Moran, & Pederson, 2007; Madigan, Vaillancourt, McKibbon, & Benoit, 2012; Roisman et al., 2017). It has been documented that mothers that experienced CM are more likely to present a nonautonomous or unresolved attachment state of mind than those without such experience (Bailey et al., 2007).

Attachment state of mind and parenting. Attachment theory stipulates that when presented with

the task of developing a relationship with their infant, mothers interact with their infant according to their internal working models. Haft and Slade (1989) suggested that generally, caregivers appear to perceive, organize, interpret, and sometimes avoid or distort emotional attachment information in ways that are consistent with their internal working models, and hence preserve their attachment state of mind.

The hypothesis that attachment state of mind predicts maternal behavior has received considerable empirical support (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985; van IJzendoorn, 1995; Verhage et al., 2016). Specifically, secure attachment state of mind in mothers is robustly associated with sensitive and supportive caregiving toward infants (Pederson, Gleason, Moran, & Bento, 1998; Shlafer, Raby, Lawler, Hesemeyer, & Roisman, 2015; Ward & Carlson, 1995; Zajac, Raby, & Dozier, 2019). Among others, Ward and Carlson (1995) examined the association between attachment state of mind and sensitivity in a group of high-risk, adolescent mothers. Their results suggested that mothers with a secure attachment state of mind are more sensitive than mothers with unresolved or insecure representations of attachment. Conversely, considerable evidence suggests that mothers with nonautonomous or unresolved states of mind display lower quality parenting behaviors (e.g., less sensitivity) than do those with secure states of mind when interacting with their infants (Pederson et al., 1998; Riva Crugnola et al., 2013; Tarabulsy et al., 2005; Zajac et al., 2019). Also, mothers with an unresolved state of mind toward attachment-related trauma such as CM show more atypical behaviors in interaction with their children than other mothers (Madigan et al., 2006; M Main & Hesse, 1990). Unresolved scales of maternal attachment state of mind have been linked to less adequate dyadic attention and emotion regulation (Riva Crugnola et al., 2013) and to more parenting problems and maltreatment behaviors (Reijman et al., 2017).

CM, attachment state of mind and parenting. While the attachment state of mind,

CM-parenting and attachment state of mind-CM-parenting associations have received important empirical support, very few studies have integrated all three variables into one model. Furthermore, authors that did examine these three variables only found partial support in favor of the attachment state of mind mediational hypothesis. Huth-Bocks, Muzik, Beeghly, Earls, & Stacks (2014) examined the association between maternal attachment state of mind and maternal positive and negative behaviors in a group of 115 mothers who had been oversamples for their experience of CM. The severity of CM was taken into account. Their results revealed that mothers with more secure attachment states of mind were likely to display more positive and less negative parenting behaviors than those with less secure states of mind toward their infants. However, the severity of the CM experienced was not related to maternal sensitivity. Similarly, Zajac and her colleagues (2019) examined whether CM experiences and attachment state of mind predicted maternal sensitivity among 178 mother-child dyads who were involved with Child Protective Services. Their results suggested CM did not predict maternal sensitivity, but attachment state of mind did. Indeed, unresolved and dismissing attachment states of mind were predictive of insensitive parenting when children were 20 months old. Taken together, these two studies highlight that although the associations between each of the variables have been well supported, the support for the mediational hypothesis is not as conclusive. In regard to the absence of association between CM and sensitivity, both groups of authors speculated that it

may be attributable to the low variance in the distribution of CM in their specific samples. Studies with more sensitive tools for CM assessment, or in a lower-risk sample would be necessary to further the understanding of the risk in this context. Furthermore, no study to our knowledge has examined the possibility that maternal attachment state of mind could act as a moderator of the CM-sensitivity association.

Psychosocial adjustment.

CM and psychosocial adjustment. The relation between CM and adjustment throughout the

lifespan is well established (see, Afifi et al., 2014; Dvir, Ford, Hill, & Frazier, 2014; Lomanowska, Boivin, Hertzman, & Fleming, 2015 for reviews). Individuals with a history of CM have been found to be at greater risk of lifetime and current depressive disorders (Capaldi, Tiberio, Pears, Kerr, & Owen, 2019; Chapman et al., 2004; Jansen et al., 2016), as well as stress related symptoms (Cougle, Timpano, Sachs-Ericsson, Keough, & Riccardi, 2010; Ford, Stockton, Kaltman, & Green, 2006), and this among individuals from high and low-risk environments. Furthermore, CM severity as well as the amount of types of CM experienced have been found to aggravate adjustment issues (Capaldi et al., 2019; Chapman et al., 2004).

In addition to adjustment difficulties that emerge throughout the lifespan of CM victims, the parenting role can represent a major life change that is closely intertwined with their own experience of CM and to which they have to adjust. Growing evidence shows that CM contributes to greater levels of reported stress in the parenting role (Ammerman et al., 2013; Steele et al., 2016). Madigan and colleagues (2014) examined how CM impacts the course of depression and anxiety in a sample of 55 pregnant-adolescent women. In this study, CM was assessed via an interview conducted during the mothers’ last trimester of pregnancy. Their symptoms of anxiety and depression were reported via questionnaires during pregnancy, as well as at 6 and 12 months postpartum. Their results revealed that sexually abused mothers were particularly at risk for sustained mood problems in the postpartum period, in opposition to the decline of symptoms observed in adolescent mothers with no such experience.

Psychosocial adjustment and parenting. Lower levels of maternal sensitivity often characterize

the parenting behavior of mothers with adjustment issues during interactions with their infant. As mentioned earlier, the concept of maternal sensitivity is derived from the attachment-based literature and refers to the ability of mothers to perceive, interpret and respond accurately to child needs, emotions and other behaviors (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Goodman, 2007). Indeed, some of the symptoms relative to poorer maternal adjustment may testify to maternal inability to respond to child needs, signals and behaviors (Lovejoy et al., 2000).

The relationship between maternal adjustment and sensitivity is well documented. Lower sensitivity is found in mothers with adjustment issues (see, Biringen, Derscheid, Vliegen, Closson, & Easterbrooks, 2014 for review). For example, lower levels of maternal sensitivity have been reported in mothers with acute symptoms of depression (Easterbrooks, Bureau, & Lyons-Ruth, 2012; Trapolini, Ungerer, & McMahon, 2008) and anxiety (Zelkowitz, Papageorgiou, Bardin, & Wang, 2009). In addition, many studies report lower sensitivity levels among mothers recruited from clinical populations in comparison to those recruited from community samples (e.g., Bailey et al., 2012; Fuchs et al., 2015).

The research is fairly consistent in providing robust associations linking maternal adjustment to CM and maternal sensitivity. However, there has been relatively less work that has combined these variables to examine whether adjustment might mediate the relation between CM and sensitivity. This demonstration is at the heart of the model that will be tested in the current dissertation.

CM, psychosocial adjustment and parenting. Considering that CM by definition occurs during

childhood and most of the time with a proximal attachment figure, transitioning into parenthood may represent a major challenge for those who have had such experiences. Several authors have noted that parenthood creates an important demand for adaptation in adults and that those who are at risk for different reasons may be less well equipped to manage this transition (O’Connor, 2003; Tarabulsy et al., 2010). In addition, becoming a parent also elicits a number of representational issues that may exacerbate personal vulnerabilities. Lieberman (2007) and others (e.g., Lyons-Ruth & Block, 1996) have postulated that the personal and projective features involved in parenthood may serve to facilitate fears that were experienced by parents when they themselves were children, making more difficult the executive functions and regulation involved in dealing with the task of parenting and the role of parenthood. In that context, mothers having trouble regulating their own emotions may show maladaptive parenting practices such as aggressiveness or withdrawal in the context of interactions with their children (Ehrensaft et al., 2015), both testifying to lower levels of interactive sensitivity. In this perspective, some authors have explored a potential mediation effect of maternal psychosocial adjustment in the relationship between CM and maternal sensitivity.

Ehrensaft et al. (2015) utilized a longitudinal design to test the influence of CM on parenting practices and the mediating influence of psychosocial adjustment difficulties among 396 mothers. Data on CM were obtained using a combination of prospective official records as well as two retrospective self-reports assessed for the first time when mothers were 22 and for the second time when they were 33. Psychiatric disorders were assessed via a clinical interview and data on parenting practices were derived from self-reported questionnaires. The results revealed an association between CM and parenting: parents

who had experienced sexual abuse spent less time with their child. Further analyses of the data showed that this relationship was mediated by symptoms of anxiety. Sexually abused parents used more avoidance strategies like emotional distancing to cope with their lack of resources to manage the complex demands of parenting (Dilillo & Damashek, 2003; Ehrensaft et al., 2015), linked to less sensitive interactions with the child.

Pereira and colleagues (2012) tested the hypothesis that parenting stress mediates the relation between CM and maternal sensitivity among 291 low-risk mother-child dyads. Any psychiatric disorder diagnosis was an exclusion criterion. CM and parenting stress were assessed through questionnaires. Maternal sensitivity was assessed based on the observation of the interaction between mothers and their 16-month-old children. The results indicated a dose-response relationship between CM, parenting stress and sensitivity: mothers who reported greater CM scores also endorsed higher parenting stress and were less sensitive in their interaction with their infants. Interestingly, the analysis of the joint effect of both CM and maternal adjustment revealed that CM history did not contribute unique variance beyond that explained by parenting stress, suggesting an indirect association between CM and sensitivity, via maternal adjustment. In other words, these findings support the idea that the precise context of parenting triggers or exacerbates adjustment difficulties in mothers with CM, which in turn undermines sensitivity.

Integrative model.

Attachment state of mind and psychosocial adjustment. Attachment state of mind has been

associated to emotion regulation in adulthood (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2008; Riggs & Jacobvitz, 2002). Research on the topic has revealed nonautonomous attachment states of mind are associated with psychosocial adjustment difficulties such as dysthymia (West & George, 2002), emotional dysregulation (Caldwell & Shaver, 2012), and suicidal ideation (Riggs & Jacobvitz, 2002). Caldwell and Shaver (2012) found that, in a sample of 388 young adults, individuals with nonautonomous attachment states of mind were more likely to exhibit emotional dysregulation and impaired resilience, which they define as the ability to regulate oneself to respond adaptively to punctual challenges. Individuals with unresolved attachment states of mind are over-represented in patients with borderline personality disorders and severe depressive or anxiety disorders (Dozier, Stovall, & Albus, 1999; Fonagy et al., 1996)

CM, attachment state of mind, psychosocial adjustment and parenting. The attachment states of

mind and their associated regulation mechanisms (or the lack thereof in the case of unresolved state of mind) are believed to influence how mothers perceive, interpret, and respond to their children’s affect (DeOliveira, Moran, & Pederson, 2005). Similarly to how they cope with their own affect, dismissing

mothers are expected to minimize their infants negative emotions, thus be unlikely to respond sensitively to these emotions. Preoccupied mothers, on the other hand, are expected to be overly involved in their children’s negative affect and to perceive these negative emotions as overwhelming or dysregulated, and thus be unlikely to respond effectively to relieve such distress. Unresolved mothers, because of their own emotional dysregulation and their ongoing lack of resolution, are expected to be most negatively affected by their children’s emotional signals. Lyons-Ruth and Block (1996) have hypothesized that infant distress could act as a trigger to the mother’s own unresolved fear and trauma and thus give rise to competing needs: 1) To take care of her child; and 2) To protect her own ability to function, to maintain her caregiving capacities. While struggling with their own overwhelming fears, mothers would thus struggle to respond to their infant’s needs (Lyons-Ruth, Bronfman, & Atwood, 1999), displaying frightened behaviors in response to the infant’s distress (Madigan et al., 2006).

Empirical evidence of the association between CM, attachment state of mind, psychological adjustment and parenting is scarce. Caldwell, Shaver, Li, & Minzenberg (2011) studied the associations between CM, preoccupied and dismissing attachment states of mind, maternal depression, and parental self-efficacy in a community sample of 76 at-risk mothers. Their results suggested that CM predicted higher levels of preoccupied attachment and maternal depression, and that CM predicted lower parental self-efficacy through indirect pathways involving preoccupied attachment and depression. Specifically, CM’s influence on maternal depression was mediated by preoccupied attachment state of mind, while its influence on parental self-efficacy was mediated by depressive symptoms.

Accounting for the developmental ecology: an addition to the CM-parenting model

Several authors have suggested that since CM are more likely in high-risk environments (Bailey et al., 2012; Dohrenwend, 2000), it may be possible to consider CM as an indicator of the level of risk that is present in the family ecology in a broader sense. Indeed, children who grow up in poverty are at greater risk of being exposed to adverse experiences of different kinds that may cause trauma (Briggs et al., 2014). High-risk family ecologies may be at the origin of multiple adverse outcomes such as maternal exposure to CM (Steele et al., 2016). In addition to providing a fertile ground for the occurrence of CM, high levels of risk may provide a context that reduces maternal ability to interact sensitively, and increase problems in maternal adjustment (Stacks et al., 2014). In that perspective, CM is perceived as a marker of the negative environment that provides the context for maternal and child development, as well as a mediator of the relationship between the quality of the home environment and parenting outcome.

Methodological Considerations and Enduring Questions

Although the results of the studies presented above guide our understanding of the relationship between maternal CM and parenting, this review of the literature raises an important limit: the studies and their results are difficult to compare and contrast, which we believe is due, in part, to the great variability in research designs and methodology. The issues are specifically addressed.

Operationalization of CM. One of the reasons why it is difficult to compare results among studies

of CM resides in that they do not all operationalize maternal CM in the same way. First, the assessment procedure is not the same among all of the studies. Although some researchers assessed CM via interviews (e.g., Madigan et al., 2014), most used a self-reported questionnaire (e.g., Chapman et al., 2004; Delker, Noll, Kim, & Fisher, 2014). This may create differences in results as in the best of circumstances, reliably measuring CM constitutes an important challenge (Madigan, Vaillancourt, Plamondon, McKibbon, & Benoit, 2016). Second, the conceptualization of CM is not the same for all authors. For some, it included a broad range of adverse childhood experiences, including abuse and neglect (e.g., Bailey et al., 2012; Chapman et al., 2004), for some others, it included only some types of CM (e.g., only physical and sexual abuse; Bert et al., 2009). Again, these differences may well influence effect sizes that are found. Third, some authors used a binary assessment (presence/absence) of CM (e.g., Ford et al., 2006), while others used a score that reflects either the severity or frequency of the CM (e.g., Chapman et al., 2004; Cougle et al., 2010). Fourth, the timing when maternal CM were assessed varies greatly among studies. For example, Madigan and colleague's (2014) longitudinal design allowed for assessing CM during maternal pregnancy. Conversely, Babcock Fenerci and colleagues (2016) assessed maternal CM seven to eleven years postpartum. These variations may have an impact on the assessment of the very sensitive subject that is CM.

Operationalization of maternal sensitivity. Similar differences may be observed in the way the

different research groups assess maternal sensitivity. First, as with CM, the assessment procedures differ greatly between studies. Some authors assess maternal sensitivity from self-reported questionnaires (Bert et al., 2009; Ehrensaft et al., 2015), whereas others assess it from observations of the mother-child dyads interactions in either short video segments or prolonged home observations (e.g., Fuchs et al., 2015; Pereira et al., 2012). When both sensitivity and CM are measured using self-reports, there is shared methodological variance that may affect findings. When observations are used, interactions may involve different types of tasks, varying from free-play tasks (e.g., Fuchs et al., 2015) to stressful tasks (e.g., Martinez-Torteya et al., 2014). Second, the timing of the assessment of maternal sensitivity also varies, ranging from assessments during early infancy (e.g., Madigan et al., 2006), toddlerhood (e.g., Bailey et al., 2012). In brief, although all these ways of measuring maternal sensitivity may be valid, it is possible to imagine that they may not