© Annie Delamatta, 2020

Participant observation of an inerdisciplinary

educational innovation project on the Saint Lawrence

River in a Grade 11 class in Quebec City

Mémoire

Annie Delamatta

Maîtrise en administration et politiques de l'éducation - avec mémoire

Maître ès arts (M.A.)

Participant observation of an interdisciplinary educational

innovation project on the Saint Lawrence River in a Grade 11

class in Quebec City

Mémoire

Annie Laurelle Delamatta

Sous la direction de :

Claire Lapointe, directrice de recherche

Barbara Bader, codirectrice de recherche

ii

Résumé

Les principes fondateurs sur lesquels les systèmes éducatifs occidentaux reposent font l’objet de nombreux débats depuis des décennies. Des études ont montré d'importantes lacunes qu'il faut résoudre (Giroux, 1988 ; Koehler et Kim, 2012 ; Shields, 2003). Il est donc primordial d’envisager des avenues structurantes qui pourraient y pallier. Afin de contribuer à cette réflexion, ce mémoire,

qui se situe dans le champ de l’administration scolaire, a pour but de réfléchir sur les pratiques éducatives innovantes afin de mieux comprendre ce qui fait appui ou obstacle à l’innovation pédagogique en milieu scolaire. La démarche méthodologique retenue s’inspire de l’ethnographie, à partir de l’observation participante d’une étude de cas unique dans le cadre du projet international d’Éducation Interculturelle à l’Environnement et au Développement Durable (EIEDD): Rapports

aux savoirs scientifiques, aux territoires et engagement écocitoyen de jeunes de la fin du secondaire en France et au Québec de Barbara Bader et Jean-Marc Lange (2017-2020,

FRQSC-ANR). Les données sont recueillies à l’aide d’enregistrements audio, de notes de journal de bord et de différents documents relatifs aux réflexions des élèves. La présente recherche porte plus particulièrement sur la démarche menée à Québec auprès de 19 jeunes de 5e secondaire en collaboration avec deux enseignantes.

Le principal apport de cette recherche est de décrire les éléments ressortis au cours de la mise en œuvre de la démarche ainsi que les réflexions qui accompagnent ce processus d’innovation pédagogique, et ce en portant une attention particulière au leadership de la direction d’école et à son rôle transformatif. Par ses observations des activités pédagogiques, et le contraste entre les entretiens des jeunes et ceux des enseignantes, cette recherche contribue à la réflexion sur les pratiques pédagogiques innovantes et émancipatrices, ainsi qu’à l’élaboration des pistes qui paraissent les plus prometteuses pour soutenir la mise en place de ce type d’innovation pédagogique.

Mots clés : éducation relative à l'environnement ; éducation au développement durable ; innovation pédagogique ; leadership transformatif ; pratiques innovantes ; collaboration

iii

Abstract

The founding principles on which western education systems hinge have been the subject of much debate for decades. Studies have shown important shortcomings in the system that remain to be addressed (Giroux, 1988; Koehler et Kim, 2012; Shields, 2003). It is therefore essential to consider structuring avenues that could alleviate them. In order to contribute to this reflection, this thesis, set within the field of educational administration, ponders innovative educational practices in order to better understand what prevents or supports pedagogical innovation in schools. To that end, the methodology is based in a participant observation of a case study with an ethnographic approach as part of the international project Intercultural Education for Environment and Sustainable Development (IEESD): Young people’s rapport to scientific knowledge, territories and their eco-citizen commitment at the end of secondary school in France and Quebec led by Barbara Bader and Jean-Marc Lange (2017-2020, FRQSC-ANR). Data are collected via audio-recordings, a journal with field notes and different documents relating to students’ reflections. This research particularly focuses on the implementation process in Quebec City, with 19 high school students in Grade 11 and in collaboration with two female teachers.

The main contribution of this research is to describe the emerging elements that support and hinder educational innovation as well as the reflections that accompany its implementation, with an emphasis on the school administration leadership and its transformative role. Through its observations of educational activities, and descriptions of the contrast between the student and teacher interview content, this research contributes to the reflection on innovative and emancipatory educational practices, as well as to the development of avenues that seem most promising to support the implementation of this type of educational innovation.

Keywords: environmental education; education for sustainable development; transformative leadership; educational innovation; innovative practices; collaboration

iv

Table of contents

Résumé ... ii Abstract ... iii Table of contents ... iv LIST OF TABLES ... viLIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ... vii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS & DEDICATION ... viii

Introduction ... 1

CHAPTER 1. THE RESEARCH PROBLEM, THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND METHODOLOGY ... 3

1. Experience-based research problem ... 4 2. Shortcomings in Education ... 6 2.1. The need for mentorship during novice teaching years ... 6 2.2. The need to study the sub-population of experienced teachers who leave the profession .... 7 2.3. The need for curriculum revision for societal transformation ... 8 3. Links between my professional experience, my master's studies and the project in IEESD ... 10 4. Theoretical Framework: transformative leadership as a lens for analysis ... 12 4.1. Defining transformative leadership ... 12 4.2. Applying transformative leadership to the research problem ... 13 4.3. IEESD as transformative pedagogy ... 18 5. Methodology: Ethnographic-inspired participant observation in a case study ... 19 5.1. Study background ... 19 5.2. Research methods & design ... 19 5.3. Research context and participants ... 21 5.4. Data collection and strategies ... 22

CHAPTER 2. RESEARCH RESULTS AND MAIN OBSERVATIONS ... 33

1. Quebec City IEESD research context ... 34 2. Chronological narrative ... 35 2.1. Important sequence of events during the IEESD project ... 35 2.2. Important sequence of events regarding the educational project activities ... 39 3. Data analysis ... 44 3.1. Contrasting profiles : teacher perspective vs. student perspective ... 44 3.2. Support received and obstacles met by teachers during the participant observation ... 48 3.2.1. Means of support: institutional and pedagogical elements ... 48 3.2.2 Means of constraint: institutional, pedagogical and cultural ... 54 CHAPTER 3. : DISCUSSION ... 59 Conclusion ... 63 References ... 65

APPENDIX A: RESOURCE DOCUMENT ... 69

APPENDIX B: EXAMPLE FOR PRODUCTION 1 ... 79

v

APPENDIX D : TEACHER INTERVIEW PROTOCOL ... 86 APPENDIX E: CHARLOTTE DANIELSON FRAMEWORK FOR TEACHING ... 87 APPENDIX F: PROPOSED CALENDAR OF EVENTS FOR THE IEESD PROJECT ... 91

vi

LIST OF TABLES

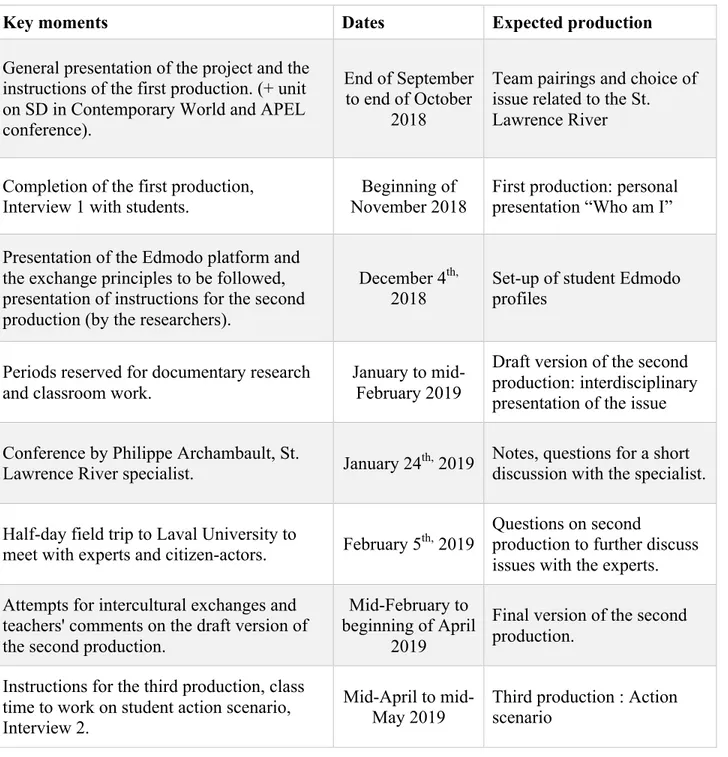

Table 1 Calendar of data collection ... 24 Table 2 Main early stages of the IEESD project implementation in the Grade 11 class... 36 Table 3 Key steps of the instructional process for the St. Lawrence Initiative... 42

vii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

EIEDD Éducation Interculturelle à l’Environnement et au Développement Durable IEESD Intercultural Education for the Environment and Sustainable Development

FRQSC Fonds de recherche du Québec - Société et Culture

Quebec research funds – Society and Culture

ANR Agence National de la Recherche

National Agency of Research

EESD Environmental Education and Sustainable Development SDG Sustainable Development Goal

APEL Association pour la protection de l'environnement du lac Saint-Charles et des Marais du Nord

Association for the protection of the St. Charles lake environment and northern swamps

viii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS & DEDICATION

First, I would like to thank my research director, Professor Claire Lapointe, and my co-director of research, Professor Barbara Bader. Your guidance, counsel, patience and investment have made the achievement of this thesis a reality. Thank you for inspiring me beyond my own vision, this project would not have been possible without you. More particularly, your passion for education and supervision have allowed me to deepen my questioning and improve the writing of this thesis. I am grateful to both of you, for the confidence and support you offered from the very beginning of this journey until its realization.

I would like to thank several of my professors as well, for it is your quality instruction that led me to become a researcher. A special thank you to Abdoulaye Anne, Mélanie Bédard, David Litalien and Joanni Joncas for teaching me the skills, rigor and methods needed to share this new-found knowledge.

Given the methodology used for this research, it is imperative to highlight my gratitude for the teachers of the Quebec City high school. Their openness to allow me to observe the educational contexts and collaboration enabled me to be at the heart of the research to explore my question. I am also grateful to the IEESD project team members for their collaboration during this project. I would also like to thank my family for their unconditional support, especially my father David, my mother JoEllen, my sisters Lindsay and Lydia, my uncle Mitch and aunt Marcia, Dee and Billy, my cousins and grandparents. Your support and love allowed me to pursue my dreams all the way in Quebec. Your prayers have given me wings to complete this memoir which, on several occasions, seemed beyond my reach. Mom, without you I would not have survived my first year as a teacher, I’m so thankful for all the ways you supported and encouraged me in my first years as a teacher, it is a blessing to have learned from such a talented and passionate teacher.

I sincerely thank all my friends in America and Quebec contributed to the realization of this research, I know you will recognize yourselves. I am grateful for all those quality moments that embellished my experience in Quebec and gave me unforgettable memories over the past two years. A most heartfelt thank you to my dear friend Etienne who was there for me every step of the way these past two years and without whom I would not have succeeded. Thank you for continuing to be such an amazing friend. And thank you to my extraordinary friends and colleagues Rachel and Beth Ann who have shown me the ropes in World Language, and continue to inspire me yearly. I am so grateful for your love and support me in this education journey.

In closing, I would like to dedicate this thesis to my cousin Zachary Cochran, in loving memory of his own pursuit, dedication and perseverance in making his dream become a reality.

1

INTRODUCTION

This thesis focuses on the leadership-related factors that support or hinder educational innovation in the educational environment. The research question explores the complexities of implementing an innovative and interdisciplinary educational project in secondary school. The nature of this research required an in-depth approach to describe and interpret participants’ behaviors, staff educational practices, and other related phenomena. Hence, a participant observation based on an ethnographic approach was employed. The data derive from participant and non-participant observations, interviews, documents, as well as field notes. The data analysis provides a basis to characterize and contrast the emerging elements within the educational environment that facilitated and challenged educational innovation, which seeks to make effective change in teaching practices (Orr & Cleveland-Innes, 2015; Shields & LaRocque, 1998). The research findings shed light on possible solutions to effectively change educational practices from a transformative leadership perspective.

This research is as part of a larger international research project conducted in five different cultural contexts in France and Quebec. This study seeks to provide a unique reflection surrounding the collaboration between the research team and the chosen educational environment. In providing insight into the structure surrounding educational innovation, this research helps open a discussion for future innovation. The main limitation of the project is the timeframe during which the participant observation was conducted in order to be included in the thesis, resulting in the exclusion of some data.

This thesis has three chapters. The first consists of two large parts. The first part presents the experiential problem, as well as the underlying educational context supporting such a research project. The relevance of the subject under study will be demonstrated through three current issues in the education system that I personally experienced during my first years as a teacher and which will lead to a more definite delineation of the research problem, the purpose of the research, and the question it intends to explore. Subsequently, this chapter deals with the theoretical framework

2

and the methodological aspects of this thesis. It includes information pertaining to transformative leadership theory, as well as the methodological approaches, sample, data collection and analysis. The second chapter describes the IEESD project in which the participant observation took place: it presents the context studied, the actors involved and a chronological narrative of the project’s evolution and the main findings. Subsequently, using the collected data, an analysis of the results is carried out to show the means of support and the constraints to educational innovation. Finally, the third chapter further examines the research findings by interpreting them in terms of the tenets of transformative leadership. This chapter is devoted to discussing potential solutions for school transformation in light of the main obstacles the IEESD project encountered.

3

CHAPTER 1. THE RESEARCH PROBLEM, THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

AND METHODOLOGY

The first part of this chapter will establish the context for conducting this research, which is first characterized by the experiential research problem, inspired by my own experience as a teacher. Following, I will outline three distinct shortcomings in education discussed in literature pertaining to pedagogical innovation and school transformation: the need for mentorship during novice teaching years, the need to study the sub-population of experienced and invested teachers who leave the profession, and the need for curriculum revision.

The second part of this chapter focuses on the theoretical framework and methodology used to address the research question. As a first step, it is important to delineate transformative leadership theory and associated practices which constitute the conceptual framework in this research. The ties between the purpose of this study and transformative leadership are thereupon demonstrated. In a second step, this section includes information regarding the research methods chosen to carry out this study, namely participant observation of a case study using an ethnographic approach. It includes a description of the chosen methodology characteristics and provides research examples to justify the use of such methods in the context of this research. Thirdly, it is important to describe the general context of the educational project, the participants and the data collection aiming at identifying what supports or hinders pedagogical innovation. Finally, there will be a discussion of the processing applied to data analysis and of the measures taken to ensure its transferability and reliability.

4

1. EXPERIENCE-BASED RESEARCH PROBLEM

My interest in educational administration was ignited by the mentors I encountered during my first few years of teaching, notably my world language supervisor, my lead teacher and my school principal who supported me throughout my learning process. My lead teacher was a valuable mentor during my first year of teaching, as her availability and counsel intrinsically shaped my instruction. Her role entailed assisting new and inexperienced teachers in their classroom management, building rapport with parents, as well as providing advice to enhance language instruction and guidance with regard to meeting the state objectives. My supervisor’s mentorship was certainly one of the biggest contributions that influenced my decision to pursue a career in education. During my first year, feedback from her numerous formal and informal observations suggested ways to improve and frame the lessons and creativity in my classroom according to the curriculum outlined by the county. This mentorship positively shaped the development of my identity as a teacher, honing the necessary educational and instructional skills to meet the needs of students and a distinguished evaluation criterion. Furthermore, the invitation to participate in curriculum development workshops during my second year, strengthened my knowledge of the material and eventually led to my being part of the curriculum development team. This mentorship consistently provided allotted time to observe other more experienced teachers, and develop innovative instructional resources to engage students as well as collaborative opportunities to create a county-wide culture of sharing among all teachers. This supportive environment exerted a salutary effect on my own professional development and mastery of the content, allowing me to build rapport with my colleagues and successfully meet the needs of my students.

Indeed, my first-year teaching was one of the most difficult challenges I have hurdled. I accepted a High School French teacher position which included five class preparations as I was the only French teacher, and therefore responsible for levels 1 through Advanced Placement. Having a native background in the French language helped open the door into a career that would be a stepping stone to accomplishing a future dream. I pursued teaching in order to better understand

5

the American education system, in the hopes of one day opening an innovative school in a developing country. However, it quickly became clear that the task at hand was much more than I had initially expected. Amidst the challenges of preparing for five different levels and developing classroom management skills, each class presented its own set of needs, which I was responsible for assessing while navigating the difficulties of the school culture. Like many novice teachers before me, the realities of the profession overwhelmed the expectations I previously had imagined as my priority. Indeed, as stated by Schaefer (2011) “for beginner teachers the dominant institutional narrative in which they find themselves as a character is one trying to keep their head above water” (p.262). In that first year, I realized that all preconceived notions of making a difference and changing lives weren’t possible until I learned how to swim.

Teaching in an underprivileged community led me to find creative ways to engage my students and captivate their interest. Indeed, these measures were indispensable to develop students’ skills and enduring understandings “as hyper-standardization becomes more pronounced in our educational climate, schooling that neither captures the attention nor engages students through traditional classroom teaching is unsurprising” (Schultz, McSurley & Salguero, 2013, p.54). Our county focus, when it came to curriculum development and implementation, was “college and career readiness.” In world language, this concept was categorized into interpersonal communication, interpretive listening and reading, and presentational goals according to each proficiency level. However, world language is a mandatory class for students who are planning to go to college. Guidance counselors encourage students to take two basic language courses to give each of them the opportunity to go to university. Nonetheless, world language, or ‘foreign language’ as it is often still referred to, remains an extracurricular course, which means it is not a requirement to graduate. To a certain extent, this stance seems to assign a depreciated value to language, as it is not considered a necessity, only an enrichment option. Therefore, students invest efforts relative to the value they attribute to the discipline, a contributing factor in the pressure faced by world language teachers who are expected to expand their programs without compromising high standards of learning while implementing instruction to enhance students’ motivation and overall outlook on language.

6

This experience as a teacher grew my interest to learn how to become actively engaged in a quest to transform educational practice. Being part of the curriculum development team initiated my desire to work together with others towards building a greater vision that provides students with an empowering education and find solutions to the current system’s shortcomings. In North American schools, administration provides the required platform as successful future change lies in the leadership of superintendents, school principals, assistant principals and lead teachers (Shields, 2003). Inquiring into ways the curriculum can be developed to support beginner and experienced teachers, this questioning led me to focus on the reasons we become teachers: making a difference in students’ lives. In an effort to develop my personal knowledge and skills with respect to the responsibility of school administrators, to innovate in a collaborative and ethical approach in order to bring about more social justice in schools, I pursued a Master’s degree in Educational Administration and Policy studies at Laval University. The invitation to collaborate in an innovative interdisciplinary project with Professor Barbara Bader enabled me to experience a concrete application of school transformation.

2. SHORTCOMINGS IN EDUCATION

2.1. The need for mentorship during novice teaching years

The challenges faced by novice teachers in regard to their professional integration have been well documented (Adoniou, 2016; Carr, Holmes, & Flynn, 2017; Koehler & Kim, 2012). Researchers have called attention to the particular vulnerability teachers face during their first years, as this period serves to form their teaching identity through practical experience in the classroom (Fantilli & McDougall, 2009; Koehler & Kim, 2012). The challenge for novice teachers’ professional integration lies in the gap between their training and the practical classroom experience, as well as the noticeable absence of support during their first years of teaching (Adoniou, 2016). The irregularity of educational support during these formative teaching years reinforces the vulnerability of beginning teachers who often lack the means to respond to their students’ needs (Koehler & Kim, 2012). The professional integration of novice teachers is therefore

7

of great importance, as the feeling of inadequacy and the need for further professional development directly impact their decision to stay in education (OCDE, 2016). In effect, the paucity of collaboration and sharing opportunities with more experienced teachers contributes significantly to the high rate of teacher turnover and their commitment to stay in the profession (Adoniou, 2016). Along these lines, Douglas (2017) underlines the importance of promoting a professional community as a means of valuing cooperative learning that applies the strategic discussions and theoretical foundations into the everyday classroom practices (Douglas, 2017). Previous studies identify mentorship as playing an essential role in teacher retention as it provides the support needed for new teachers to develop confidence, and master their craft while building a sense of belonging (Adoniou, 2016; Johnson, 2001; Sowell, 2017).

2.2. The need to study the sub-population of experienced teachers who leave the profession

It is well known that the high challenges faced by novice teachers are critical factors in the reasons for high turnover (Adoniou, 2016; Certo & Fox 2002; Fantilli & McDougall, 2009). Although there is a considerable body of literature concerning turnover rates in novice years, the factors that contribute to the decision of more experienced teachers to leave the classroom remains to be more thoroughly investigated. The gap in literature is surprising, nonetheless, a study conducted at Stanford University focuses on “invested leavers” from three regions in the United States to determine the cause of their departure from education. Glazer (2018) defines “invested leavers” as teachers who have overcome the ‘survival period’ (Huberman, 1989) of their career, found confidence and success in their teaching methods and have thus entered the ‘stabilization and commitment’ period (Huberman, 1989). Moreover, these teachers are also qualified as invested as they demonstrated significant commitment to their craft by pursuing higher education degrees and certifications. By all means of observation and factors outlined by previous studies on attrition, these teachers should not have left the profession. However, in each case of invested leaver studied, the teachers experienced a strenuous situation between their aspirations for entering the profession and the demands placed on them by the administration. Glazer (2018) states that “these invested leavers experienced a loss of authority which interfered with their ability to achieve pedagogically,

8

and what emerged was a dissonance between their feeling of efficacy, their belief (and experience) that they could achieve the results they desired, and their inability to do so because of new limitations on their work” (p.57). In effect, the change in their professional environment challenges their self-efficacy and competence, leading them to feeling overwhelmed and without any control over the situation, ultimately resulting in their decision to leave the profession. This study supports the need to document this sub-population of teachers more attentively, in order for administrators to circumvent preventable turnover.

2.3. The need for curriculum revision for societal transformation

Another factor having cause much debate in education is that of the school curriculum.

Bowles and Gintis (1976) present a theory of correspondence, inspired by the work of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1966) who first identified schools as conduits for the reproduction of social inequalities. Bourdieu highlights the importance of cultural factors, the persistent behaviors acquired in the familial setting which symbolize one’s conduct in social life. Another important critical sociologist, Bernstein (1975), discusses from another angle the differences between social relationships in his analysis of social classes. By inquiring into the differences in social classes in the relation to the knowledge of language, Bernstein (1975) finds that language is another learned mechanism that is reproduced according to one’s social class. The use of elaborate codes and analytical symbols demonstrates a higher manifestation of language, distinguishing the upper class, while the working class uses more restricted codes and condensed symbols.

Similarly, the theory of correspondence points out links between institutionalized strategies that serve to propagate social inequalities. By structuring social interactions and individual rewards to reproduce the work environment, the American school system replicates the expected personality and the internalization of a social destiny in each individual’s mindset. The economic and social role of young people is transmitted by values, norms, personal aspirations, modes of speech and learned conduct within the family (Bowles & Gintis, 1976). Hence, students’ familial

9

heritage contributes to the hierarchical success of each individual, through the advantages or disadvantages that lie in the socioeconomic status of their family from generation to generation. Bowles and Gintis (1976) conclude that the stability of the economic systems relies solely on whether “the consciousness of the strata and social classes which compose it remains compatible with the social relations which characterize it as a mode of production” (p.147).

In looking at American schools as a salient vehicle for the reproduction of the dominant social class in society, Bowles and Gintis (1976) also present existing parallels between education and capitalism. Given that the education system prevents social mobility by conforming to a class-centered logic in which teaching is limited to the acquisition of specific skills necessary to function in the hierarchical structure of society, inequality between social classes is perpetuated. Disparity between schools encourages compliance with the hierarchy of employment, where low-income classes do not receive the same opportunities as high-income ones. The impact of capitalism on child-rearing patterns allows for the intergenerational transmission of social inequalities from the family structure (Bowles & Gintis, 1976).

Education aiming at creating a better world must be grounded in a larger question that seeks to uncover the purpose for schooling, the reason of its existence (Giroux, 1988). Critical pedagogy points out that the viability and survival of the education system relies on social justice in order to improve privileges for all social groups and ensure that success is accessible for all individuals. Indeed, Giroux (1989) states that “public schools need to be organized around a vision that celebrates not what is but what could be, a vision that looks beyond the immediate to the future, and a vision that links the struggle to a new set of human possibilities” (p.10). Central to the critical pedagogy theory is the view of schools as public democratic spheres as well as the view of teachers and students as transformative intellectuals (Giroux, 1989, 2004). By considering them as such, it undergirds a counter-ideology that completely redefines teacher and student behavior by changing the instrumental and management pedagogies which “call into play the political and normative interests that underlie the social functions which structure and are expressed in teacher and student

10

work” (Giroux, 1988, p.101). This concept of teachers and students as transformative intellectuals, places them in a unique position to challenge the subjectivity imposed on them by cultural forms and political organization which reproduce social inequality. Instead, they are equipped with a new form of power that devises a cultural production based on agency and a structure where “the role of teaching cannot be reduced to merely training in the practical skills, but involves, instead, the education of the class of intellectuals vital to the development of a free society, then the category of intellectual becomes a way of linking the purpose of teacher education, public schooling and in-service training to the very principles necessary for developing a democratic order and society” (Giroux, 1988, p.126).

3. LINKS BETWEEN MY PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE, MY MASTER'S STUDIES AND THE PROJECT IN IEESD

As mentioned above, I had the opportunity to participate in an Environmental Education and Sustainable Development research project aiming at educational innovation and student automatization. EESD is mentioned by most authors as a means to empower young people to take action and become agents of change (Chawla & Cushing, 2007; Hayward, 2012; Pruneau & al., 2001). Indeed, alarming statistics reveal that 836 million people continue to live in extreme poverty, resulting in more than 160 million children suffering from malformation due to the lack of proper nutrition (UNICEF, 2015). Mobilizing global efforts remains a critical need to alleviate the growing inequality between developed and developing countries (Nyoni, 2010). Recognizing the importance of engaging future generations, UNESCO has developed learning objectives for education for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). As the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals is ambitious, UNESCO aims for a large-scale mobilization and involvement to accomplish their set objectives (UNESCO, 2017). Applying learning objectives for each SDG transforms the way of thinking about education for sustainable development in the skills on cognitive, socio-emotional and behavioral elements at different levels of progression. By integrating SD into all aspects of the school's operations, we can rethink leadership, management, day-to-day practices, curriculum and activities. The learning objectives are categorized into

socio-11

emotional, cognitive and behavioral spheres aimed for the development of social, critical thinking, and action-related skills. Youth engagement is identified as a critical factor in the changes that need to be made for their participation allows them to identify themselves as part of the process (Wals & Jickling, 2010). Their contribution is increasingly appreciated, and advances in technology are facilitating a communication network, creating a larger community of international collaboration (UNICEF, 2015, Wals & Jinckling, 2010). It is for this reason that it is essential to develop critical thinking and promote environmental commitment in sustainable development so that young people are able to participate in public debates, search for solutions and eco-social innovation. Different levels of participation are related to EESD (Wals & Jickling, 2010), thus the sense of belonging and empowerment, as well as values develop during a student’s life beginning in primary school (Gadotti, 2010).

One of the goals of the education system is to convey a pedagogical ideal so that students can thrive in their professional and personal environment (Durkheim, 1999). In fact, schools instill the moral values that serve as a foundation for society (Duru-Bellat & van Zanten, 2012), highlighting their role of production since these values reinforce the habits and behaviors of future generations (Durkheim, 1999). Given the current challenges of the education system and the need to involve future generations of young citizens, the search for solutions continues. Many scholars support the creation of meaningful opportunities, projects, and teaching practices that involve children and youth and enable them to become agents of change (Brown, 2016; Driskell & Chawla, 2009; Malone, 2016; Satchwell, 2016). However, most of the research in this field focuses its attention on children, particularly in elementary school. What seems to be missing from the many reflections and developments to cultivate an environmental identity among future generations, is greater knowledge of the obstacles faced in engaging adolescents leading to the underlying research question for this study: What elements support or prevent an innovative and interdisciplinary educational project in EESD in secondary schools?

12

4. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: TRANSFORMATIVE LEADERSHIP AS A LENS FOR ANALYSIS

4.1. Defining transformative leadership

The inherent mandate for schools to prepare students in their role as citizens who will contribution to society requires sustainable leadership. Corroborating studies by Hayward (2012), Steg and Vlek (2009) and Chawla and Cushing (2007) emphasize the cultivation of a sustainable global economy that engages politicians, teachers and entrepreneurs in behaviors conducive to a more just and viable world. Therefore, we must understand the “relationship between sustainability and democracy. (…) this relationship can be captured as follows: deep sustainability requires deep participation, while shallow democracy will lead to shallow sustainability” (Wals & Jickling, 2010, p.79). On the one hand, the worldwide socioeconomic gaps entail the need for effective and viable leadership to break the cycles of inequity. On the other hand, privileged groups of people seem to have the power of decision, as they hold the influential voice over the marginalized (Shields, 2003, 2017). Therefore, the need for leadership grounded in an ethical framework and a sincere concern for social justice is obvious to many researchers, educators and social activists who promote a leadership for change “in which social, political, and cultural capital is enhanced in such a way as to provide equity of opportunity for students as they take their place as contributing members of society” (Shields, 2010, p. 572).

In calling for a high standard of leadership, Shields (2003, 2010) advocated for leaders to critically examine the ideologies, attitudes, and assumptions that maintain disparities in our society in order to promote a democratically just education system. Armed with what Shields (2010) refers to as ‘enlightened understanding’, transformative leadership challenges the status quo by enacting a “deconstruction and reconstruction of knowledge frameworks that perpetuate the inequities (…); offering a balance of critique and promise related to existing beliefs, structures, policies and practices” (p.2). Early articulations of the concept of transformative leadership are associated with

13

work by several authors, particularly Burns (1978) in business administration, as well as Giroux (1983) and Starratt (1991) in educational administration, according to Shields (2010) and Langlois (2011). Shields (2010) attributes the transformative ideals to Freire’s (1970) “call for personal, dialogic relationships to undergird education, because without such relationships, he argues, education acts to deform rather than to transform” (p. 566) which, she contends, ultimately resulted in founding transformative leadership theory as a response to this premise.

4.2. Applying transformative leadership to the research problem

In writing about the nature of transformative leadership, one must clarify the distinction between transformative and transformational leadership as both concepts have been applied in various contexts. While these terms have been used synonymously in prior work, Shields (2003, 2011) and Langlois (2011) have documented how the core components of transformative leadership are distinct from transformational leadership and other theories in that it begins with a reflection on the social material realities. Fostering a hegemony of power and privilege prevents students from having equal opportunities to attain success and prosperity. In explaining transformative leadership, Shields (2003) holds that this style of leadership goes beyond the organization or institution in order to transform society, whereas transformational leadership primarily aims for efficiency within organizations. The practical foundation of the theory is based on leaders taking account of differences in power in order to address the resulting injustices. According to Shields (2011), the questions which are at the heart of transformative theory seek to determine ways to create inclusive learning environments, better understand and recognize the role educators play in empowering students, as well as the influences individual particularities have on student commitment in order to identify those who are “marginalized, excluded, or disadvantaged by a given decision and [those who are] privileged and included” (p.10).

14

According to Shields, transformative leadership combines eight instrumental tenets to ensure equitable change and identifies key elements for leaders to exemplify in their commitment to integrity and democracy. The eight tenets encapsulated by Shields (2011, 2017) are :

1. working towards equity and justice to effect deep and equitable change; 2. acknowledging the ways power and privilege propagate inequity;

3. deconstructing social-cultural knowledge frameworks that generate inequity and reconstruct them on the basis of equitable distribution of power;

4. achieving balance in individual and collective purposes (public and private good); 5. seeking transformation: liberation, emancipation, democracy, equity, and

excellence;

6. acknowledging our interdependence and interconnection with others; 7. balancing promise and critique;

8. calling for moral courage and activism in leaders.

Langlois (2011) offers an interesting perspective in her exploration of ethics as a fundamental concept in the application of transformative leadership. Citing scholarly literature, Langlois (2011) delineates ethics “as an intellectual discipline offering tools for reflection. Ethics can also be approached in terms of specific language, such as vocabulary, concepts, or reasoning modes, in order for those who use ethics to identify and gain knowledge of certain fundamental aspects of human experience” (p. 88). Thus, a relation with ethics exists in the articulation of transformative leadership’s mandate, as the context of applied ethics is made visible through the application of “a process allowing the analysis of underlying principles, such as a decision that leads to specific action” (p.88). In the delineated tenets, transformative leaders exhibit an openness to diversity and learning from others, as well as respect for different perspectives and traditions, while the power of their decisions serves as a tool for moral and ethical use (Shields, 2003, 2011). Therefore, ethics encompasses the basis for each of the eight tenets identified by Shields.

15

The interconnectedness of the second and third tenets provide an overview of some of the salient aspects of transformative leadership. Indeed, awareness of the manifestations of privilege, social conditions, prejudices and familial settings is essential in addressing the injustices students face daily. Shields (2017) explains that injustice derives directly from frameworks of knowledge such as color-blind racism, homophobia, xenophobia, and classism. To palliate the propagation of these social-cultural thought patterns and conduct, Shields (2010, p.47) posits the importance of building communities of difference where educational leaders uphold respect for diversity of language, race, gender, ethnicity and perspectives. A learning context built on inclusion seeks to understand difference, and provides interventions to reconstruct new and powerful knowledge frameworks. In order to do so, it is crucial to recognize the investment of time needed to apply this notion to schools as initiating a discourse that builds tolerance, mutual understanding, and multicultural values of inclusion and respect within school contexts defies current cultural rules and expectations (Shields, 2003, 2017). Thus, educational leaders are tasked with organizing activities to create a sense of unity as one community, enabling common ground to be reached and a progressive appreciation for differences which were formerly perceived as an obstacle (Shields, 2017). In mobilizing parents and students towards a common objective, “a shared vision is the driving force (…) inspiring action, acting as a benchmark for decision making, helping individuals and groups determine whether a suggested action or activity is consistent with and advances the mission of the community as a whole, then it provides the focus and energy for learning” (p. 49). Thereby, it is in educational leaders’ commitment to an ethical and social justice-based leadership that transformative change can occur (Shields, 2003).

Expanding on transformative leadership, Shields (2011) articulates individual and collective purposes “in terms of mutual benefit and societal change” (p. 6). In reflecting on the well-being of our democratic society with a global perspective, she explains how to achieve balance in public and private goods. It becomes clear at this point that this leadership inherently mandates a proactive strive to work towards transformation. In their aim to reach liberation, emancipation, democracy, equity, and excellence, educational leaders must take students’ unique needs into

16

account (Shields, 2011, 2017). Acknowledging these personal circumstances and individual particularities enables educators to provide better support for each student in the development of her or his full potential (Shields, 2011, 2017). It is only in doing so that both curriculum and educational practices can optimize learning outcomes and “help young people envision and create a just, diverse, and multicultural society” (Shields, 2003, p. 64). This tenet positively correlates to the recognition of our interdependence and interconnection with others. Shields (2017) insists on the importance of having a global perspective as individuals have a reciprocal influence over one another. Interdependence requires to be informed on local and global matters and to develop an overall curiosity beyond ourselves.

It is in the questioning that educational leaders can elucidate the purposes of schooling as well as the changes to be enacted in the curriculum and practices in order to achieve transformative goals (Shields, 2010). In an interview, Shields (2017) elaborates on the fundamental task of balancing the promise with the critique, where action also results in the provision of hope. The term promise is grammatically categorized as a verb and a noun, providing context for the parallel made with the tenet. When thinking about the well-being of a democratic society, both the public and the private good must be balanced through critique “for the promise of schooling that is more inclusive, democratic, and equitable for more students” (Shields, 2010, p. 570). The strive and efforts to foster inclusive norms call for moral courage and activism as transformative leaders must consistently take an ethical stance to uphold the outlined values (Shields, 2011, 2017).

Ensuring the promise of an ethical and social justice approach to change entails considerable responsibilities. Transformative leadership addresses the challenges in schools through the implementation of solutions and contextualized contributions by inspiring leaders to move towards an inclusive school culture where educational practices are related to students’ interests and culture. Embracing transformative leadership theory as a framework for analysis, this research thesis aims to identify the elements that support and hinder an educational innovation project that seeks to understand young people’s relationship to their territory, their rapport to

17

scientific knowledge and learning as well as their forms of commitment on SD issues related to the St. Lawrence river.

18

4.3. IEESD as transformative pedagogy

Transformative pedagogy creates collaborative learning environments to foster student creativity, agency and identity development (Gagné & Soto Gordon, 2015; Harrell-Levy & Kerpelman, 2010). Transformative pedagogy practices challenge the status quo by questioning students’ beliefs and understandings to broaden the focus (…) by emphasizing the relevance not only of transmitting the curriculum and constructing knowledge but also of enabling students to gain insight into how knowledge intersects with social realities and power relations » (Gagné & Soto Gordon, 2015, p.534). Transformative pedagogy is rooted in meaningful exchanges between students and teachers, where mutual learning is anticipated to develop cognitive and emotional skills such as problem-solving, confidence, patience, interpersonal communication, honesty and a respect for diversity (Gagné & Soto Gordon, 2015; Harrell-Levy & Kerpelman, 2010; Pavlou, 2020). By advocating for student engagement and interest, transformative pedagogy emancipates students as 21st century citizens and facilitates their actions and reflection according to Freire’s ideals.

The international research project in which this Master’s study is framed, examines young people’s relationship to the world from a sociological point of view, by studying their relationship to knowledge1. The IEESD research project created a project-based learning opportunity for youth through a unique cross-cultural collaboration supported by interdisciplinary learning, practical engagement based on their interests and an enriched learning environment. This project sought to equip youth in exploring their identity through a connection to their local territory where students would collaborate with groups from another cultural context as well as real-world experts and citizen-actors to broaden their learning beyond the classroom into the 21st century. It is important to reiterate that EESD provides a platform supporting social justice and the empowerment of young people as it aligns with the SDGs. The IEESD project provided the support and resources to further develop students’ knowledge, facilitate discussions to enable students to formulate opinions, and

1

19

foster a cooperative learning environment to inspire creativity, connection and societal action ensued from their reflections. These values seem to reflect similar commitments as seen in the communities of difference. Parallels with transformative leadership form in the similar quest to factor the understanding of the environment in which students learn to enhance their educational outcomes and to develop a multipurpose set of abilities fit for a multicultural society.

5. METHODOLOGY: ETHNOGRAPHIC-INSPIRED PARTICIPANT OBSERVATION IN A CASE STUDY

5.1. Study background

This thesis is embedded in a larger study in intercultural education in science, environment and sustainable development (IEESD) whose objective is to document Grade 11 students’ interest with regard to the sustainable development (SD) of a river they live alongside. More specifically, the IEESD project seeks to investigate five different academic and cultural settings, in rural, urban and semi-urban areas, in order to better understand Grade 11 students’ knowledge, concerns, positions and commitment (or lack of commitment) to this issue. To do so, five comparative case studies were conducted in different cultural and environmental settings in Quebec and France. A mixed method was employed in which both qualitative and quantitative data collections techniques and analyses were used to bring out "typical profiles" of young people in terms of their relationship to scientific knowledge and territories, their dispositions and practices, as well as their eco-citizen commitment with regard to social, political, economic, ethical or ecological issues that they associate with the SD of a river.

5.2. Research methods & design

The research methods for this qualitative study emerged from the possibility of experiencing the questioning of transformative leadership and educational innovation in relation to

20

social and environmental challenges. Guided by an ethnographic approach, a participant observation methodology was used to collect data, analyze and interpret it, and present the outcomes of this study. The particular use of participant observation in the interdisciplinary educational innovation project allowed for immersion into its day-to-day progress and access to extended observations. Being part of the research team, I had the opportunity to live the reality of the project’s implementation and examine various phenomena, as indicated by Berg (2001), such as student and teacher behaviors, impressions, and experiential learning. Participant observations are deemed as “descriptive studies and studies aimed at generating theoretical interpretations. In the end, participant observation aims to generate practical and theoretical truths about human life based on the realities of everyday life” (Jorgensen, 2015, p. 13-14).

As this study seeks to investigate the complexities of educational innovation, its epistemological stance is ethnographic. The concept of ethnography is delineated by Berg (2001) as a “practice [that] places researchers at the heart of what they study. From this point of view, researchers can examine various phenomena as perceived by the participants and represent these observations in the form of reports” (p.134). An ethnographical approach was utilized as a tool in attempt to provide an in-depth account of educational innovation beyond the scope of the IEESD project implementation, showing the complexities of the interactions, perspectives, and issues confronted. Since ethnography is conducive to a more representative depiction of the cultural and social environment being investigated, this approach allowed to uphold the rigorous standards noted by Berg (2001). He posits that in being a part of said environment, ethnographers should be driven beyond the description of the social world investigated as “they must strive to understand their populations, and if possible, explain their activities” (p.139).

Another key element that contributed to the research design is the choice of location for conducting the study. Of the five academic and cultural settings, the IEESD project seeks to investigate in France and Quebec, only one was used in order to meet the requirements for this Master thesis. As the participant observation consisted in the exploration of one particular academic

21

and cultural context, a case study field technique was strategically employed to further analyze the data results. According to Jorgensen (2015), “case studies conducted by way of participant observation attempt to describe comprehensively and exhaustively a phenomenon in terms of a research problem” (p.19). The extensive case description conducted allowed for rich and relevant findings regarding patterns encountered in the academic environment (Berg, 2001).

5.3. Research context and participants

Our study draws on several sources of data to accurately examine the research question. This case study recorded the developments of the IEESD project in a Grade 11 class in the Languages and World concentration, an intercultural openness and language-oriented program at a secondary school located in Quebec City. Numerous attempts were made to recruit secondary teachers, in science, language, ethics and cultural studies and contemporary world. Given the substantial resistance from teachers to commit to a project outside of the curriculum, there appeared to be a fear concerning additional workload that would not serve in the results of the end-of-year national exams. Potential participants were recruited by word-of-mouth with the help of a personal connection.

This study happened in collaboration with two teachers, a Spanish language teacher, responsible for the Languages and World Concentration Focus project, and a Contemporary World teacher (a class which covers topics such as history and geography). The withdrawal of the Contemporary World teacher, due to conflicts with the administration, led to the English teacher’s recruitment. At the time of the study, both teachers had significant experience teaching secondary or high school education and had collaborated on several educational projects. The Spanish teacher has 11 years of secondary education experience, entrusted with all levels of secondary (1-5) which is equivalent to Grade 7 through Grade 11. Her responsibilities to teach Spanish, Culture and Ethics as well as lead extracurricular activities qualify her duties at 92% capacity. The English teacher has over 30 years of experience including 8 years of substituting both in primary and secondary

22

education, during which time she was also involved in several school committees. This project marked her final collaboration prior to entering retirement.

The secondary school is considered to be a Brundtland2 establishment, located in an environment surrounded by a commercial area, near bridges crossing the St. Lawrence river. It is important to note that the river is not visible from the school, and the general landscape surrounding the school is of the commercial area. Overall, the socio-economic environment is quite privileged and particularly educated. There has been a considerable increase in the number of immigrants and students with an immigrant background, which was reflected in our sample as 27% of students in the school are issued from immigration. The participants in this study included 21 students, ages between 15 and 16 years of whom 19 were able to complete all the activities involved for the duration of the project. Of the 21 11th grade class students, 6 students (3%) were not born in Quebec, and 8 students (4%) have parents who were not born in Quebec.

5.4. Data collection and strategies

The strategies for data collection, processing and analysis were based in a qualitative research approach according to the methods and techniques associated with participant observation, ethnography and case study research. The following table identifies the main moments when I collected data for this study.

2 The network of Brundtland Green Establishments (EVB-CSQ) initiated in Quebec in 1993 by Centrale des

syndicats du Québec (Central Labor Union of Quebec), in collaboration with partners, including RECYC-QUÉBEC, the EVB-CSQ network, now has 1,500 institutions registered since its creation. Composed mostly of primary and secondary schools. It is an institution that is described as thinking globally and acting locally to foster a sustainable future.

Key moments during participant observation Dates

23

Table 1. Calendar of data collection

Collaboration with teachers to plan project calendar September 19th 2018

Presentation of the instructions for the first production October 18th 2018

Interview 1 with students November 6, 7 et 82018 th

APEL Conference with Marie-Christine Alarie October 31st 2018 Presentation of the Edmodo technology platform and the exchange

principles to be followed, presentation of instructions for the second

production (by the researchers). December 4

th 2018

Online Edmodo assistance December 11th 2018

Conference with Philippe Archambault January 24th 2019 Classroom visit: assist students during period reserved for documentary

research. February 1st 2019

Non-participant classroom observation (English) February 8th 2019

Interview with English Teacher February 15th, 2019

Non-participant classroom observation (Spanish) March 5th 2019

24

Aspects of participant observation presented by Kawulich (2005) include collaborating with participants as well as “selecting key informants, the processes for conducting observations, deciding what and when to observe, keeping field notes, and writing up one's findings” (p.3). Kawulich (2005) also points out that there as four stances the researcher can adopt: complete participant, participant as observer, observer as participant and opposite extreme stance. The role of observer as participant was adopted by this study for this stance “enables the researcher to participate in the group activities as desired, yet the main role of the researcher in this stance is to collect data, and the group being studied is aware of the researcher's observation activities. In this stance, the researcher is an observer who is not a member of the group and who is interested in participating as a means for conducting better observation and, hence, generating more complete understanding of the group's activities” (p.7). During this study all groups including students, teachers and the larger research team members, were made aware of the observation activities conducted. Kawulich (2005) suggests that the focus on data collection rather than participation, with a clear indication of the observation activities involving the group being studied, provide the basis for this stance to be regarded as the most ethical approach. Participant observations are often used as a tool in ethnographic research to “study the meaning of behavior, the language, and the interaction among members of the culture-sharing group” (Creswell & Poth, 2018, p.90). Research literature voices the importance of acquiring the confidence of the participants in order to gain access (Berg, 2001; Bogdan & Biklen, 1997; Creswell & Poth, 2018). In this study, establishing rapport with the participating teachers allowed for an insider standpoint to describe the academic culture within the classroom.

According Creswell and Poth (2018), the relevance of case study research is the exploration of “a real-life, contemporary bound system (a case) (…) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information” (p.96). In this instance, the case study was focused on the implementation, over the span of the school year, of an interdisciplinary project in a Grade 11 class in Quebec City, and was used as an exemplary case regarding the complexity of educational innovation in an educational environment. Case study research typically uses field notes with descriptive and reflective notes post observation, as well as interview and observational

25

protocols (Creswell & Poth, 2018). This methodological approach allowed to depict the fundamental reality of the project implementation, and to gain insight into the contextual conditions that supported or hindered the educational innovation.

The data collection strategies are as follows: 1) Participant observations

2) Non-participant observations 3) Semi-directed interviews 4) Journal with field notes

5) Variety of documents: Project resource document and student work (3 productions)

a. Participant observation: A participant observation was conducted to seek reflections on the embodied experiences articulated by the 19 students, two teachers and three research team members through two waves of interviews, classes visits and time spent with them over a period of ten months. The participant observation also involved attending conferences organized at the school, and meetings with the international IEESD research team. The field notes described the observation of day-to-day routines, activities, facial expressions and body language. In addition to the descriptive material, the field notes contained my own personal reflections, with an emphasis on feelings, issues, ideas and impressions. These observations allow to formulate generalizations and interpretive theories regarding the everyday life situations encountered throughout the implementation of the St. Lawrence Initiative educational project (Jorgensen, 2015; Kawulich, 2005). For instance, in a recently published multi-approach research, the participant observation documented activities, student roles and concept development to “access non-verbal expressions of students in order to determine how interactions and communications between group members unfolded” (Aflatoony, Wakkary & Neustaedter, 2018, p.440). In comparison, an ethnographic study on the different types of musical activities used a participant observation in two periods. The first period involved daily observations over a month where a researcher became an additional teacher in the class while during the second period, the same researcher observed the class once every two weeks for four months (Pérez–Moreno, 2018). As can be seen in these two studies, the

26

characteristics of a participant observation approach and data collection are determined by each case.

b. Non-participant observation: Prior to the interviews with the teachers, two non-participant observations were conducted to identify the strategies they used in lesson planning and instructional approach as well as the elements contributing to the classroom environment. The non-participant observation of classroom instruction included the learning activities, lesson structure and materials, classroom management techniques, facial expressions and body language. Each non-participant observation session lasted between 1 hour and 1 hour and a half and was written up in ethnographic field notes. An example is found in Varley and Busher (1989) who studied the spectrum of interruptions that teachers faced in 11 junior high schools. Non-participant observation of 16 teachers documented the types of interruptions, the time and duration of occurrence, the context in which it occurred and the students’ reactions.

To better understand the real pedagogy used in secondary schools, non-participant observation of instruction was conducted in English and Spanish classes using an observation protocol for courses taught by participating teachers. Semi-structured interviews followed each observation to further discuss the teachers’ pedagogy. The protocol used to gather information during the observations stemmed from the Charlotte Danielson Framework for Teaching3. This observation protocol identifies critical attributes for teacher evaluation and was approved by the principal investigators of this research. An example of a similar study was the use of the Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) protocol in five California hospitals in order to facilitate direct observation of contextual factors and strategies supporting and hindering the implementation and adaptation process (Mitchell & al., 2017). In the same manner, the protocol used in this study seeks

3 The Framework for Teaching is a common language for instructional practice that is grounded in a philosophical

approach to and understanding of great teaching and the nature of learning. The Framework defines a distinct aspect of an instructional domain; two to five elements describe a specific feature of a component. Levels of teaching performance (rubrics) describe each component and provide a roadmap for improvement of teaching.

27

to gain insight and impressions on the classroom experiences to establish a profile of participating students and teachers. The Charlotte Danielson Framework for Teaching (see Appendix E) provides a basis for evaluation, identifying key contributing factors in each profile.

c. Semi-structured interviews: According to Corona & al. (2012), semi-structured interviews are commonly used in qualitative research as these interviews “have the potential to generate rich data that allow us to examine important issues” (p.791). From this perspective, a study investigating the reasons for teacher turnover in a Canadian context interviewed teachers “to allow the voice of the novice teacher to inform the research” (Fantilli & McDougall, 2009, p.816). In this study, two waves of semi-structured, face-to-face interviews were completed with the same group of Grade 11 students so as to discuss the content of their productions. The transcription and coding between interviews allowed for more in-depth insight into the initial study findings to help build the questions for the second interview guide. For more in-depth understanding of participants’ experiences, and growth throughout the project, the second interview guide also took into account the two final student productions. The interview guides for the two waves consisted of different questions. Interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes in length and were conducted at the school over three lunch periods. However, given the requirements for a Master’s thesis, this present study only discusses findings from the first wave of interviews. The results from the questionnaires administered in the first phase of the IEESD project to approximately 600 young people in France and Quebec, guided some of the interview questions, although not administered to the students of the case study. The primary objective of the first wave of semi-structured interviews was to clarify some questionnaire answers, better cognize students’ perspectives on the places they live and frequent often as well as their opinions on what the school offers them in terms of environmental questions and SD issues. The first guide’s open questions were designed to establish a “typical student profiles” and better understand the internal and external resources available to students so as to offer them a more meaningful and socially relevant educational environment. Specific questions on the first production were also formulated to elicit a discussion of their reflections after completing the first production. The interview guides were verified by the ethics committee, and then adapted for use in the other four academic and cultural contexts of the larger IEESD project.