Mortalité après éclaircie commerciale

de peuplements résineux du Québec

Mémoire

Karin Rita Rivera Miranda

Maîtrise en sciences forestières

Maître ès sciences (M.Sc.)

Québec, Canada

iii

RÉSUMÉ

L‟éclaircie commerciale est une activité relativement nouvelle au Québec et son utilisation est en augmentation depuis ces dernières années. Dans ce contexte, le ministère des Ressources naturelles du Québec a entrepris une étude des effets du traitement dans les peuplements forestiers de la province. La présente investigation analyse la mortalité des tiges dix ans après l‟éclaircie commerciale. Avec l‟appui du modèle ForestGales, il a été possible de déterminer les vitesses critiques du vent nécessaires au déracinement et à la rupture de tiges d‟épinette noire (Picea mariana (Mill.) B.S.P.) et de sapin baumier (Abies balsamea (L.) Mill.). À partir de régressions logistiques, les variables les plus influentes sur le risque de mortalité au niveau des tiges individuelles ont été identifiées: le taux d‟éclaircie, l‟espèce, le diamètre et le type de dépôt. Finalement, cette étude propose un modèle capable de prédire le risque de mortalité pour les populations étudiées.

v

TABLE DES MATIÈRES

RÉSUMÉ ... III TABLE DES MATIÈRES ... V LISTE DES TABLEAUX ... VII LISTE DES FIGURES ... IX REMERCIEMENTS ... XIII AVANT-PROPOS ... XV

1 INTRODUCTION GÉNÉRALE ... 1

1.1 Éclaircie ... 1

1.2 Chablis ... 3

1.3 Facteurs d‟influence de la mortalité après éclaircie... 4

1.3.1 Conditions climatiques ... 5

1.3.2 Topographie ... 5

1.3.3 Edaphologie et système racinaire ... 6

1.3.4 Peuplements forestiers ... 6 2 OBJECTIFS ... 9 SCIENTIFIC PAPER ... 11 3 INTRODUCTION ... 19 4 METHODOLOGY ... 21 4.1 Study sites ... 21 4.2 Plots implementation ... 22 4.3 Forest description ... 23 4.4 Statistical analysis ... 27 5 RESULTS ... 31

5.2 Predicting mortality at the stand level with the ForestGALES model... 33

5.3 Predicting mortality at the tree level... 35

5.3.1 Thinning rate and windthrow probabilities ... 36

5.3.2 Deposit type and mortality ... 37

6 DISCUSSION ... 41

7 CONCLUSION ... 47

8 CONCLUSION GÉNÉRALE ... 49

vii

LISTE DES TABLEAUX

Table 1. Number of plots by stand type ... 24

Table 2. Number of plots by deposit type ... 25

Table 3. Stands characteristics in treated plots before and after the treatment ... 26

Table 4. Estimates from linear mixed-effects model ... 31

Table 5. Mortality rate in basal area by stand type ... 32

Table 6. Mortality rate in basal area by deposit type ... 32

Table 7. Critical wind speed obtained from ForestGALES model - black spruce and balsam fir ... 33

Table 8. Multiple regression statistics - Black spruce ... 34

Table 9. Multiple regression statistics - Balsam fir ... 35

ix

LISTE DES FIGURES

Figure 1. Plots distribution in relation with bioclimatic sub-domains ... 22 Figure 2. Sample plot spatial distribution ... 23 Figure 3. Correlation between (a) topex, (b) uprooting critical wind speed and mortality rate. ... 34 Figure 4. Probability of mortality by species according to thinning intensity on a till deposit. ... 37 Figure 5. Probability of mortality in control plots according to major deposit types . 38 Figure 6. Probability of mortality in lightly thinned plots (25%) according to major deposit types ... 38 Figure 7. Probability of mortality in heavily thinned plots (50%) according to major deposit types ... 39

xi

A Dios y a mi familia, en especial a mi esposo Arnaud y a mis hijos Iann y Noah.

xiii

REMERCIEMENTS

Je tiens tout d‟abord à remercier mon directeur de recherche, le professeur Jean-Claude Ruel qui m‟a offert la possibilité d‟effectuer ce travail de maîtrise. C‟est grâce à son support, son aide et encouragement, que j‟ai pu réaliser cet ouvrage.

Merci aussi à M. Stéphane Tremblay, responsable du projet au ministère des ressources naturelles du Québec, pour ses conseils et ses commentaires judicieux.

Des remerciements sincères à toutes les personnes qui ont collaboré à l'élaboration de ce projet, spécialement aux spécialistes du Centre d‟étude de la forêt, M. Marc Mazerolle et M. Pierre Racine.

Merci à tout le Département des sciences du bois et de la forêt et à l‟Université Laval.

Je voudrais aussi exprimer ma gratitude à tous mes amis qui m‟ont aidé d‟une manière ou d‟une autre au progrès de ce travail.

Finalmente, agradezco a toda mi familia, en especial a mi esposo Arnaud por su apoyo y comprensión, sin ellos todo esto no hubiera sido posible.

xv

AVANT-PROPOS

Le présent ouvrage a été rédigé dans le cadre d‟une maîtrise en sciences forestières et est présenté sous la forme d‟un mémoire de publication. Il a été conçu selon les critères de présentation adoptés par le comité des programmes de 2ième et 3ième cycles en sciences forestières de l‟Université Laval, en juillet 1998. On retrouve dans le manuscrit intitulé “Mortality after commercial thinning in softwood stands of Quebec, Canada” écrit en anglais par l‟auteure, le directeur et le collaborateur gouvernemental de ce mémoire. L‟analyse des résultats et la rédaction de l‟article ont été faites principalement par l‟auteure. L‟article scientifique inclus dans le présent document sera soumis ultérieurement pour publication.

1

1 INTRODUCTION GÉNÉRALE

Le vent a démontré son pouvoir d‟altération des paysages, notamment dans les forêts aménagées et modifiées par l‟homme. Au fil du temps, le vent est devenu, pour les aménagistes et sylviculteurs, un facteur fondamental à prendre en considération afin d‟en limiter les impacts parfois dramatiques sur un peuplement ou même sur l‟économie de toute une région. Les vents, responsables de rupture d‟arbres ou de déracinement, ont été identifiés comme une menace significative au succès des coupes partielles (Ruel et al. 2003a).

Les dommages générés par les vents provoquent des pertes économiques dans les forêts aménagées du monde entier (Zeng et al. 2010). En Europe, pendant la tempête de décembre 1999, entre 150 et 195 millions m3 de bois furent mis à terre, et la France, pays le plus affecté lors de cette catastrophe naturelle, a connu une perte de 140 millions de m3 (Bomersheim 2000). Ces cas de désastres naturels ont incité les forestiers européens à prendre des mesures pour la réduction des risques, comme par exemple en évitant de retarder les travaux d‟éclaircie (Bomersheim 2000).

Les interactions entre les différents facteurs climatiques, topographiques, édaphiques, les caractéristiques des peuplements forestiers et les traitements sylvicoles pourront être à l´origine d´éventuelles perturbations suite aux travaux d‟éclaircie (Ruel 2000). Les différentes combinaisons de ces facteurs peuvent augmenter les probabilités d‟un grave chablis (Ruel 1995). Ces chablis pourront, entre autres, interrompre la planification, modifier les réseaux hydrographiques, et augmenter les coûts d‟exploitation (Stathers et al. 1994, Mitchell 1995).

1.1 Éclaircie

L‟éclaircie consiste à couper une partie des tiges dans un peuplement ayant au moins atteint le stade du perchis, sans toutefois avoir atteint la maturité, en vue de favoriser la croissance des tiges restantes (Bureau du forestier en chef. 2013). Cette diminution de densité permet de réduire la compétition en offrant plus d‟espace pour la croissance des tiges restantes (Savill et Evans 1986). Ainsi, l‟éclaircie vise à amener le peuplement à sa composition idéale et à favoriser individuellement les meilleurs sujets en leur donnant progressivement un espace suffisant pour les placer dans les conditions de croissance les plus favorables (Bary-Lenger et al. 1999). Grâce cette

diminution de la densité, l‟éclaircie pourrait mener à un meilleur contrôle de l‟accroissement du peuplementet ainsi optimiser l‟utilisation de l‟ensemble des produits marchands récoltés durant la révolution.

Se nomme éclaircie commerciale le traitement sylvicole pratiqué dans un peuplement forestier régulier d‟une seule strate, de couvert fermé et au stade de prématurité (MRNFP 2003), dont les bois abattus ont des dimensions marchandes et une valeur permettant de compenser une partie ou la totalité des frais de récolte. Dans ce sens, Smith et al. (1997) ajoutent que durant une éclaircie commerciale les arbres sont exploités sans considérer la relation entre leur valeur et le coût de leur exploitation. En conservant relativement intacte la canopée, la production totale par unité de surface varie peu en fonction du traitement. L‟éclaircie commerciale a pour but principal l‟obtention d‟arbres de plus fort diamètre à partir de la stimulation de la croissance diamétrale des arbres (Smith et al. 1997). Sur ce point, Tremblay et Laflèche (2012) indiquent qu‟une bonne réussite du traitement sylvicole se mesure suivant la capacité des arbres résiduels à réagir rapidement et favorablement à l‟ouverture du couvert forestier. En outre, la production est meilleure lorsque les éclaircies sont plus faibles et plus fréquentes.

Des études ont démontré que certains peuplements éclaircis pouvaient être plus sensibles au chablis. Ainsi d'importantes pertes ont été observées dans des sapinières matures ou lorsque l‟éclaircie prélevait plus de 40% de la surface terrière (Hatcher 1961). De même, Holt et al. (1965) soulignent les dommages considérables survenus dans des sapinières gaspésiennes à la suite d‟opérations d‟éclaircies. En effet, l‟éclaircie augmente la pénétration du vent dans les peuplements et peut amplifier le risque de chablis pour plusieurs années (Gardiner et al. 1997). De plus, comme l‟affirme Harris (1989), une éclaircie dans un peuplement fermé peut sévèrement réduire la stabilité au vent, et dans un même temps l‟auteur indique qu‟un contrôle de la densité du peuplement, à travers des éclaircies précoces et fréquentes, améliorera la stabilité du peuplement puisqu‟il permettra un meilleur développement du système racinaire. Cependant, Smith et al. (1997) expliquent que, à la suite d‟une éclaircie, le rapport H/D diminue et de ce fait la résistance des arbres au vent augmente.

Par conséquent, la mortalité varie selon les études et des recherches sont nécessaires pour adapter et optimiser les modalités de l‟éclaircie, particulièrement au

3 Québec où la réalisation des éclaircies commerciales est peu documentée et où le traitement a surtout été appliqué dans des peuplements naturels n‟ayant pas subi d‟intervention préalable.

1.2 Chablis

Se désigne chablis tout arbre, renversé, déraciné ou rompu par le vent ou brisé sous le poids de la neige ou du givre (Ressources naturelles Canada 1995). Le chablis est un processus complexe résultant de facteurs naturels et de leurs interactions avec des facteurs anthropiques (Stephens 1956). Ce processus universel joue un rôle important dans la dynamique des peuplements au niveau de la régénération naturelle et de la croissance des individus, de même que dans la dynamique des sols (Ruel 1995).

Un chablis se produira si le moment appliqué par le vent et le poids de l‟arbre qui penche est supérieur à la résistance de la tige, dans le cas d‟un bris de tige, ou des racines, dans celui du déracinement. Ainsi la plus faible résistance au niveau des racines ou de la tige déterminera laquelle des deux ruptures se présentera (Petty et Worrell, 1981 dans Moore 2000). Le moment de flexion critique auquel l‟arbre peut résister a été déterminé pour certaines espèces et conditions de croissance, en simulant les charges appliquées par le vent via un système de câble et de treuil. Une de ces premières études, mise en œuvre par Fraser (1962) et dont les résultats furent confirmés par d‟autres études menées par Fraser et Gardiner (1967), Smith et al. (1987), Fredericksen et al. (1993), montrait une corrélation entre le moment critique en flexion et le poids de la tige.

Durant des vents violents, les arbres entrent dans un état de stress impliquant une aire en tension et une autre en compression, lesquelles correspondent respectivement aux côtés face au vent et sous le vent. Selon Smith et al. (1987) l‟aire en compression cèdera avant celle en tension. La chute, le basculement, la rupture, ou la simple déformation de l‟arbre seront dépendantes de la force du vent, du poids de l‟arbre, de l‟ancrage au sol, et du comportement mécanique du houppier (Drouineau et al. 2000).

En relation avec ces effets, on observe dans la nature trois types d‟adaptation des arbres confrontés au vent: la modification de la distribution du bois dans le tronc,

l‟amélioration du système d‟ancrage, ou l‟altération de la forme et de la taille du houppier (Mergen 1954). Certaines études ont montré des cas de chablis à des vitesses bien inférieures aux prédictions et les auteurs attribuent cet effet au caractère pulsatoire du vent. Drouineau et al. (2000) soulignent ainsi l‟importance d‟un raisonnement dynamique pour l‟étude du phénomène de chablis.

1.3 Facteurs d’influence de la mortalité après éclaircie

Les facteurs influençant la mortalité après éclaircie peuvent être distingués en deux grands types, biotiques et abiotiques. Le premier groupe correspond aux variables de taille, d‟espèce, de type de peuplement, ou de santé des individus, alors que le second inclut l‟intensité des vents, la topographie, les sols, et les perturbations passées (Kuers et Grinstead 2006).

L‟étude des variations au sein de différents groupes d‟espèces a permis d‟observer une relation entre l‟effet du vent et certains facteurs comme la tolérance à l‟ombre, la densité du bois, et la persistance des feuilles (Everham et Brokaw 1996). Par exemple, les feuillus, particulièrement lors de la perte du feuillage durant l‟hiver, demeurent moins susceptibles au chablis que les conifères (Drouineau et al. 2000).

L‟occurrence d‟un chablis dépendra non seulement de la vitesse, de la durée, ou de la fréquence du vent, mais aussi des caractéristiques du peuplement, des espèces, des hauteurs et diamètres, de la surface des houppiers, de la profondeur de l‟enracinement, ou de la densité de peuplement (Coutts 1983, Gardiner et al. 1997, Peltola et al. 2000), et des facteurs géographiques et topographiques (Quine 2000).

Il est important de signaler que les conditions de réalisation de l‟éclaircie auront un impact sur les peuplements résiduels. Un des facteurs fondamentaux pour réduire le risque de chablis est le moment d‟intervention de l‟éclaircie (Everham et Brokaw 1996). De plus, dans une étude expérimentale sur les impacts de l‟éclaircie commerciale, Bertrand et Bolghari (1970) sont arrivés à la conclusion que, 10 ans après la réalisation d‟une éclaircie par le bas et de faible intensité dans un peuplement âgé de 45 ans, les parcelles traitées subissaient un plus faible taux de mortalité.

5

1.3.1 Conditions climatiques

Les principaux facteurs déterminant les climats des différentes régions de la terre sont les masses d‟air, les courants marins, l‟inclinaison du globe terrestre, et l‟altitude. La combinaison de ces facteurs influe sur la température et les précipitations, la radiation solaire, l'humidité, et d'autres éléments qui définissent les particularités d‟un climat. La température, les précipitations et le vent sont le plus souvent considérés comme les éléments les plus importants d'un climat pour la foresterie (Savill et Evans 1986). Pour la présente étude, le vent est reconnu comme le principal facteur climatique influençant la mortalité après éclaircie et ainsi a été l‟unique facteur considéré et développé dans ce projet de recherche.

En effet l‟exposition au vent est l‟un des facteurs critiques qui influe sur l‟incidence du chablis (Ruel 2000). En plus d‟être la principale cause de mortalité dans un peuplement, les vents violents peuvent provoquer des malformations ou retarder la croissance. Ces vents peuvent également occasionner des perturbations majeures à la planification forestière et diverses pertes économiques dues au stockage prolongé, aux bois non récoltés, à la diminution de l‟accroissement dans les peuplements résiduels, ou aux raccourcissements des révolutions (Savill et Evans 1986). Le nombre de chablis est en relation avec la vitesse du vent ; il est cependant complexe de fixer une limite de vitesse au-delà de laquelle le risque de chablis serait significatif (Ruel 1995).

1.3.2 Topographie

Le vent est reconnu comme un des principaux facteurs responsables de l‟occurrence des chablis notamment dans les régions d‟altitude (Savill et Evans 1986). Les caractéristiques topographiques ont une forte influence sur le comportement du vent et donc sur l'exposition au vent (Ruel et al. 2002). L‟exposition, la pente, les variations topographiques locales, modifient la direction et la force des vents endémiques et de tempêtes (Alexander 1967). Les peuplements situés sur des pentes pleinement exposées au vent sont les plus sensibles au risque de chablis. De plus, dans le cas de pentes extrêmes, la pente opposée au sens du vent pourra elle aussi subir des dommages dus à la turbulence des masses d‟air suite à leur sortie de cet obstacle horizontal. Généralement la vitesse des vents est plus importante dans les parties moyennes et supérieures des versants et ainsi ceux-ci sont responsables de davantage de chablis dans ces zones (Navratil 1995).

1.3.3 Edaphologie et système racinaire

Le système racinaire, les propriétés du sol et l‟interaction entre ces deux éléments sont les facteurs définissant la résistance d‟un arbre au déracinement (Cremer et al. 1982). La profondeur de l‟enracinement dépendra des qualités de drainage du sol ainsi que de sa rigidité, sa granulométrie et son épaisseur (Stokes et al. 1995). La capacité d‟ancrage des arbres sera liée à la distribution et à la qualité d‟ancrage des racines respectivement dépendante de la texture et de la consistance du sol.

En outre, Coutts (1983) identifie quatre principaux facteurs d‟ancrage d„un arbre: - les forces de tension des racines face au vent;

- le poids du plateau racinaire;

- la résistance des racines sous le vent dans la zone d‟articulation; - la résistance du sol situé sous le plateau racinaire.

La morphologie du système racinaire sera en relation avec le type de sol. Effectivement, dans des sols mal drainés et peu oxygénés, se développeront des racines fines et peu profondes (Savill et Evans 1986). Les arbres munis de racines superficielles, et notamment situés sur des sols humides ou de faible résistance au cisaillement, seront particulièrement sensibles au chablis (Savill et Evans 1986). Certains auteurs ont montré par ailleurs, qu'outre les contraintes mécaniques générées par les oscillations de forte amplitude sur l'arbre, celles-ci peuvent être à l'origine d'une modification des propriétés physiques des sols notamment argileux et humides, qui peuvent passer à l'état plastique, voire liquide. Ce phénomène permet de comprendre la prépondérance des déchaussements sur sol humide (Drouineau et al. 2000). Aussi, la capacité de résistance des arbres à l‟action du vent sera liée à l‟importance de la carie au niveau des racines (Savill 1983).

1.3.4 Peuplements forestiers

L‟ampleur des dommages suite à une tempête de vent est fonction des caractéristiques du peuplement forestier et plus particulièrement de la hauteur de ses arbres (Peterson 2000). Les arbres les plus hauts sont les plus sensibles à subir des dommages ou à être brisés. En effet, le moment de flexion occasionné par le vent à une vitesse donnée est fonction du bras de levier, qui augmente lui-même avec la

7 hauteur (Savill et Evans 1986). Cependant des conditions extrêmes de vents peuvent affecter des peuplements dès une hauteur de 5 mètres (Savill et Evans 1986).

L‟âge et la composition du peuplement figurent parmi les facteurs importants à considérer, puisque la vulnérabilité au chablis augmente avec l‟âge et varie selon certaines espèces (Ruel et al. 2001). Comme l‟ont démontré Ruel et Benoit (1999), les sapinières présentent une vulnérabilité supérieure qui va en s‟accroissant avec l‟âge et, selon Whitney (1989), les arbres plus âgés auraient une plus grande proportion de pourriture au niveau des racines.

De plus, Ruel et al. (2001) indiquent que la mortalité des espèces augmente au cours des trois premières années après l‟éclaircie, le taux annuel de mortalité diminuant entre les troisième et cinquième années. En effet, durant le processus de fermeture de la canopée, l‟absence de contact entre les cimes ne permet pas de dissiper l‟énergie de turbulence du vent (Cremer et al. 1982).

L‟état sanitaire des tiges est un autre facteur à considérer pour évaluer le risque de mortalité suite à une éclaircie commerciale. La présence de caries du tronc augmentera le risque de bris de tiges (Ruel et Benoit 1999). Silva et al. (1998) ont identifié que les défauts du bois, en l‟occurrence les fentes pour Abies balsamea, peuvent être considérées comme un indicateur potentiel de vulnérabilité au chablis. Ruel (2000) a démontré que Abies balsamea avait davantage tendance à casser plutôt que de se déraciner lorsque des fentes étaient présentes.

Afin d‟intégrer l‟effet des différents facteurs sur le risque de chablis, plusieurs modèles ont été conçus pour prédire la vitesse critique du vent responsable du déracinement ou de la rupture des tiges dans les forêts de résineux. C‟est le cas du modèle ForestGales établi par des britanniques pour l‟évaluation des dommages causés par le vent à l‟intérieur des peuplements de conifères non ou faiblement éclaircis; ou encore du modèle HWIND conçu pour estimer les impacts du vent en bordure de peuplement dans les forêts finlandaises (Gardiner et al. 2000). Le modèle ForestGales calcule la rugosité aérodynamique du peuplement forestier et répartit l‟effet de friction également entre les arbres alors que le modèle HWIND calcule le moment de flexion produit par la prise au vent du houppier. Pour le présent projet de recherche, ForestGales sera utilisé pour la modélisation des risques de chablis, puisqu‟il a déjà fait l‟objet d‟une adaptation pour les espèces de l‟est du Canada (Ruel et al. 2000).

9

2 OBJECTIFS

Cette étude s‟appuie sur un réseau de placettes distribuées dans la province de Québec. Ce réseau comporte des paires de placettes, l‟une ayant subi une éclaircie commerciale, l‟autre étant gardée comme témoin. Le but de cette étude est de préciser le niveau de mortalité après une éclaircie commerciale et d‟en identifier les facteurs responsables. Dans un second temps, cette étude devrait caractériser la variable ou le facteur le plus influent sur la mortalité des espèces. Enfin, un modèle capable de prédire les risques de chablis devra être validé en supposant qu‟une augmentation éventuelle de mortalité après éclaircie serait associée à ce phénomène. Ce projet de recherche devrait ainsi apporter une meilleure connaissance sur la dynamique des peuplements suite à des travaux d‟éclaircie, en permettant, conjointement aux autres volets de l‟étude, d‟évaluer l‟intérêt sylvicole et économique de réaliser ce type d‟opération forestière.

Pour répondre aux objectifs mentionnés, les quatre hypothèses suivantes ont été proposées.

La première hypothèse H1 suppose que l‟exposition au vent influence le taux de mortalité. La probabilité de mortalité augmentera en lien direct à la fois avec la vitesse régionale moyenne du vent et avec l‟exposition liée à la topographie (facteur TOPEX - voir méthodes).

L‟hypothèse H2 définit les modalités de l‟éclaircie commerciale comme un facteur influençant le risque de mortalité après traitement. On prévoit ici que le niveau de pertes va augmenter avec l‟intensité de l‟éclaircie.

L‟hypothèse H3 suggère que les caractéristiques du peuplement demeurent une variable très influente sur la mortalité après une éclaircie commerciale. Le niveau de pertes augmentera avec l‟âge du peuplement. Il sera plus élevé dans les sapinières et plus faible dans les pinèdes.

Enfin, l‟hypothèse H4 suggère que les caractéristiques édaphiques influenceront aussi le niveau de pertes. Ainsi, les pertes seront plus élevées sur les sols minces ou

11

Scientific paper

13

Mortality after commercial thinning in softwood

stands of Quebec, Canada

Rivera-Miranda, K-R.

Département des sciences du bois et de la forêt, Université Laval Québec (Québec) Canada, G1V 0A6

Ruel, J-C.

Département des sciences du bois et de la forêt, Université Laval Québec (Québec) Canada, G1V 0A6

Tremblay, S.

Direction de la recherche forestière, Ministère des Ressources naturelles 2700, rue Einstein, Sainte-Foy (Québec) Canada, G1P 3W8

15

ABSTRACTThe effects of wind on the forest and its potential income are widely known. The current strategies of ecosystem-based management will involve new silvicultural prescriptions which could generate changes in stand stability. Commercially thinned stands of southern Quebec were monitored for 10 years in order to understand the negative and positive effects of this treatment in previously untreated stands. The present study was conducted in order to identify the most influential factors on mortality after commercial thinning, quantify basal area losses, and finally evaluate a windthrow hazard evaluation model. The study focuses on three species: black spruce (Picea

mariana (Mill.) B.S.P), balsam fir (Abies balsamea (L) Mill) and jack pine (Pinus banksiana Lamb.).

In an operational context, 153 pairs of permanents plots (thinned and unthinned) have been established and inventoried before and after the treatment. Thereafter, the permanents plots were monitored every five years. The first stage of the study consisted in calculating the critical wind speed needed to uproot or break the stems using a modified version of the ForestGALES model. A correlation analysis was performed relating the observed losses and the critical wind speed; only for black spruce was a significant correlation detected. The research has demonstrated that a late thinning in high density stands tends to increase mortality. A mixed logistic regression was calibrated to identify the variables affecting the probability of mortality. Individual tree mortality probability is mostly influenced by the species, diameter at breast height, the thinning rate and the deposit type. The observed losses in basal area at stand level showed that black spruce experienced the highest losses, followed by jack pine, while balsam fir ended up being the species with the lowest losses. The morphologic characteristics of the glaciolacustrine-4GA (fine texture) deposits make these sites the most vulnerable to mortality. Finally, it has been identified that mortality increases as thinning rate increases. This indicates the need for proper stand selection and treatment application in order to minimize mortality after thinning.

Keywords: Commercial thinning, windthrow, black spruce, balsam fir, jack pine, ForestGales.

17

RÉSUMÉLes effets du vent sur les valeurs forestières et les revenus économiques sont largement reconnus. Les nouvelles stratégies de l‟aménagement écosystémique s‟accompagneront de prescriptions sylvicoles qui pourront générer une modification de la stabilité des peuplements. La mise en pratique de l‟éclaircie commerciale dans le Québec méridional a été évaluée à la fin des années 1990 dans l‟objectif de comprendre les impacts négatifs et positifs du traitement sur des peuplements auparavant non traités. La présente étude a été menée dans l‟objectif d‟identifier les facteurs les plus influents sur la mortalité après éclaircie commerciale, de quantifier les pertes en surface terrière 10 ans après coupe et finalement d‟évaluer un modèle de prédiction de mortalité par chablis. L‟étude concerne trois espèces: l‟épinette noire

(Picea mariana (Mill.) B.S.P), le sapin baumier (Abies balsamea (L) Mill) et le pin gris

(Pinus banksiana Lamb.).

Dans un contexte opérationnel, 153 paires de parcelles permanentes (éclaircies et non éclaircies) ont été établies et inventoriées avant et après le traitement. Après le traitement, les parcelles permanentes ont été remesurées tous les cinq ans. La première étape de l‟étude consistait à calculer la vitesse critique du vent nécessaire au déracinement et à la rupture de la tige à l‟aide d‟une version modifiée du modèle ForestGALES. La vitesse critique du vent a été mise en relation avec les pertes observées mais seule l‟épinette noire a montré une relation significative. Une régression logistique mixte a été ajustée afin d‟identifier les variables influençant les probabilités de perte. La probabilité de mortalité des individus est principalement influencée par l‟espèce, le diamètre à hauteur de poitrine, le taux d‟éclaircie et le type de dépôt. Les pertes observées en surface terrière au niveau du peuplement montrent que l‟épinette noire est l‟espèce subissant le plus de mortalité, suivi du pin gris tandis que le sapin baumier a connu le moins de pertes. Les dépôts glaciolacustres à texture fine ont été les plus sensibles au chablis. Les peuplements traités étaient âgés, ce qui a pu contribuer à une augmentation du taux de mortalité. Celui-ci a augmenté en fonction de l‟intensité d‟éclaircie. Cela met en évidence la nécessité de bien cibler les peuplements à traiter et les modalités d‟intervention pour minimiser les pertes.

Mots-clé: Éclaircie commerciale, chablis, épinette noire, sapin baumier, pin gris, ForestGALES

19

3 INTRODUCTION

Canada‟s forest represents about one-tenth of the world‟s forest, and Quebec province constitutes 20% of it (Burton et al. 2003). Quebec‟s forest is considered an important ecosystem, not only because of its economic impact in the province but also because it provides habitat for more than 200 bird species and 60 mammal species, while the lakes and watercourses are home of approximately 100 fish species (MRNQ 2013). Furthermore the Quebec‟s forest is considered a great value for actual and future generations in Canada, for which the government focuses its efforts to achieve a responsible forest management. The silviculture - defined by (Côté 2003), as the art and

science of controlling the establishment, growth, composition, health, and quality of forest and woodlands to meet the diverse needs and values of landowners and society on a sustainable basis - will be the key element to achieve the government targets.

Commercial thinning is a relatively new silvicultural practice in Quebec and at the same time has a large potential use. It should be considered as an important tool to handle the forest under the pillars of ecosystem-based management or in a context of intensive forest management. The main goals of commercial thinning are to increase the harvested stand value, through the promotion of the growth of residuals trees, increasing the stand quality, releasing suppressed individuals, and removing undesirable species (Smith et al. 1997, Tarroux et al. 2010). After thinning, the residual trees will benefit with an increase of the photosynthetic rate resulting in an acceleration of diameter growth (Landsberg and Sands 2011). However, a late thinning could bring unexpected consequences, such a decrease in tree growth or an increase in mortality rate (Mergen 1954, Prégent 1998, Tremblay and Laflèche 2012).

Windthrow hazard can become more important after silvicultural practices such as thinning (Mergen 1954, Hatcher 1961, Ruel 2000). The interaction between environmental factors, such as wind exposure, topography and soil, and the stand characteristics will determine the windthrow risk (Cremer et al. 1982, Ruel 1995, 2000). Nevertheless, the wind is going to penetrate more easily into the stands because of the gaps left by the thinning operation. These changes in the stand stability are likely to generate an increase in the mortality rate in the subsequent years after the silvicultural treatments (Moore 2000, Ruel 2000, Cimon-Morin et al. 2010). This effect is likely to be more important in natural stands that were previously untended (Ruel 1995).

In order to improve the knowledge related to the effects of commercial thinning, a permanent sample plots network was implemented by the Quebec Ministry of Natural Resources between the years 1997 and 2000 in the eastern Canadian forest. This network was established and conducted following current guidelines. This study, which examines mortality 10 years after thinning, is part of a large group of researches that look at various aspects of commercial thinning. We present data on stand basal area losses, which allow the identification of the main influential factors in windthrow hazard and finally we propose a model able to predict the probability of mortality after commercial thinning.

21

4 METHODOLOGY

4.1 Study sites

The study was initiated by the Quebec Ministry of Natural Resources through the implementation of a permanent sample plots network. The plots were distributed in the northern temperate vegetation zone which is dominated by deciduous and mixed stands and also in the boreal vegetation zone characterized by coniferous stands. The main species found in the plot network were black spruce, balsam fir and jack pine.

Quebec is a large territory and represents a wide latitudinal, longitudinal and climate variation, which will influence directly the nature of the forest stands (Saucier et al. 2009). Southern Quebec is characterized by a south-north gradient within a mean annual temperature range from -2,5 to 5 °C (Proulx et al. 1987, Robitaille and Saucier 1998). There is an altitudinal climatic gradient comprising a mean temperature annual decrease of -0.6 ° C par 100 m of elevation. Finally there is also a continental gradient, on the longitudinal axis, with variations from west to east, denoting changes in precipitation that becomes more intense eastward (Saucier et al. 2009). The yearly rainfall regime varies from 950 to 1130 mm which classifies the region as sub-humid. This area is located in a climatic zone affected by westerly winds (Proulx et al. 1987).

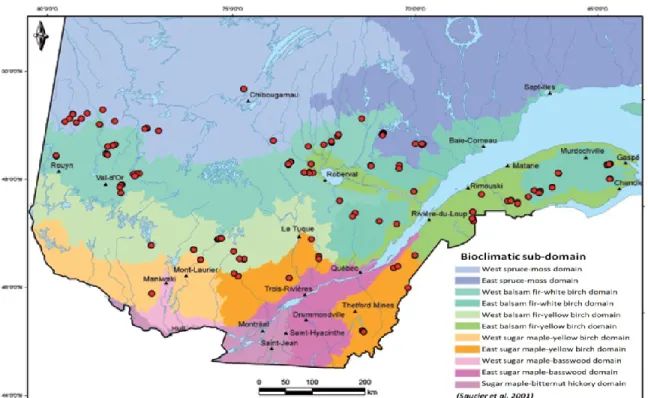

The plots were located in 4 bioclimatic domains (MRNQ 2013) (Figure 1):

Acer saccharum – Betula alleghaniensis domain (orange) covers the

hills bordering the southern Laurentian plateau and the Appalachians; Abies balsamea – Betula alleghaniensis domain (light green)

stretches westward as far as central Québec, between latitudes 47o and 48oN, and encompasses the Gaspé peninsula, the Appalachian hills east of Québec City, the Laurentian foothills north of the St. Lawrence River and the lowlands of Lake Saint-Jean;

Abies balsamea – Betula papyrifera domain (dark green) occupies

the southern portion of the boreal zone;

Picea – Mosses domain (blue) stretches approximately to the 52nd N parallel, and its northern boundary coincides with the boundary of the continuous boreal forest subzone.

Four main stand types were present in the network (MRNF 2009):

Pure stands; EE (Picea mariana), SS (Abies balsamea) and PgPg (Pinus

banksiana)

Mixed softwood stands: EPg (Picea mariana and Pinus banksiana), ES (Picea mariana and Abies balsamea), PgS (Pinus banksiana and Abies

balsamea).

Mixedwood stands where hardwoods are the most important: PeE (Populus spp. and Picea mariana)

Mixed stands where Bj (Betula alleghaniensis)is the most abundant. Soil types were classified into the deposit type inventoried.

4.2 Plots implementation

This project is based on a network of 306 permanent plot samples, established by the Ministry of Natural Resources. Each study area comprises a pair of 400 m2 circular plots, one treated and one untreated (control) (Figure 2). Before treatment, the main site characteristics (topography, drainage and slope) and the dendrometric characteristics had to be similar for both plots. Control plots were installed in the center

23 of an untreated square area (100 m x 100 m) with the objective of avoiding edge effects. Treated and untreated plots centers were separated by 150 m. The plots were inventoried before and after the treatment. The commercial thinning was applied following the regulations established by the MRN at that time (MRNFP 2003). Before the treatment, all the trees with a DBH greater than or equal to 9.1 cm were measured using 2 cm DBH classes. After the treatment, the DBH was measured in millimeters. Marked trees were felled manually (almost 60% of plots) or mechanically (about 40%). Skid trails were created according to the physical environment constraints; therefore their location was independent from the plots. In addition, for stand height evaluation, five coniferous and representative trees from the dominant and co-dominant layers were selected. The main topographic and soil variables were noted. Inventories were made five and ten years after treatment (2002-2005, 2010-2011) (Tremblay and Laflèche 2012). During the second inventory the current status codes could not allow to identify accurately the mortality type of the trees. Therefore, in the present study, the mortality variable includes standing dead trees, uprooted trees, and broken trees.

4.3 Forest description

The difficult access to certain areas 10 years after the first data collection only allowed a total of 238 plots to be retained for the study; these plots were distributed around southern Quebec and include a total of 15419 trees inventoried. The most

representative stand types in our study were EE (black spruce) SS (balsam fir) and PgPg (jack pine). Five other stand types were also found: EPg, PgE, ES, CC and Bj (Table 1). For deposit type, we identified 10 different types (Table 2), the most representative deposit being deep till (1A).

Before the treatment, the mean stem density was 2061 trees per hectare. This number decreased to 1400 tree/ha after thinning, and we found a mean thinning rate of 42.2%. After the treatment, the mean DBH decreased from 15.7 cm to 14.5 cm. The basal areas of the stands before and after treatment were 39.5 m2/ha and 22.8 m2/ha respectively. PgPg was the only main stand where the basal area before thinning was around 29.3 m2/ha, a value much lower than the other forest types (Table 3).

Table 1. Number of plots by stand type

Description Stand Code Species Plots

CC Thuja occidentalis 4

EE Picea mariana 88

PgPg Pinus banksiana 58

SS Abies balsamea or Picea glauca 42

EPg Picea mariana and Pinus banksiana 25

ES Picea mariana and Abies balsamea 5

PgE Pinus banksiana and Picea mariana 11

Mixed stands, deciduous 50 -75% with 1 important deciduous and evergreen specie

PeE Populus and Picea mariana 2

Mixed stands where the Betula

alleghaniensis is 50 to 75% Bj Betula alleghaniensis 3

Evergreen stands > 75% with one principal specie

Evergreen stands > 75% with two principal species

25 Table 2. Number of plots by deposit type

Deposit type Description Deposit code Plots

Till

Loose or compact deposits, without sorting, consisting of rock flour and angular to subangular elements.

1A 92

Glaciolacustrine (fine) Deposit composed of silt, clay and fine sand. 4GA 24

Outwash Deposit composed primarily of sand and gravel,

sorted in distinct layers. 2BE 26

Ice-contact Deposits consist of sand, gravel, pebbles,

stones, and rounded to sub-rounded blocks. 2A 22

Glaciolacustrine (coarse) Deposit consists of sand and sometimes of

gravel. 4GS 28

Shallow till Very thin or absent deposit: where the rocky

outcrops represens more than 50% of the surface 1AR 19

Weathering materials

Deposit consists of angular sediments of various sizes. It is generally made of fine materials (clay to gravel).

8A 18

Marine Deposit consists of sand and sometimes

gravel, generally well sorted. 5S 6

Active dune

Deposits bedded and well sorted, generally composed of sand with a particle size ranging from fine to medium.

Table 3. Stands characteristics in treated plots before and after the treatment

DBH (cm) 15.65 1.45 14.48 1.55

Density (trees/ha) 2061.33 546.79 1400.36 429.05 Basal area (m2/ha) 39.47 10.50 22.81 6.54

Thinning rate(m2/ha)(%BA) 16.66 (42.21%) 7.75

DBH (cm) 15.74 1.40 14.39 1.69

Density (trees/ha) 2224.95 581.53 1477.12 479.67 Basal area (m2/ha) 42.86 10.26 23.71 6.97

Thinning rate(m2/ha)(%BA) 19,16 (44.69%) 8.13

DBH (cm) 16.21 1.48 14.72 1.25

Density (trees/ha) 2040.28 496.20 1359.03 349.55 Basal area (m2/ha) 41.81 10.11 22.88 5.39

Thinning rate(m2/ha)(%BA) 18.92 (45.26%) 7.63

DBH (cm) 14.84 1.07 14.16 1.42

Density (trees/ha) 1699.07 322.99 1189.67 298.54 Basal area (m2/ha) 29.30 5.90 19.30 4.70

Thinning rate(m2/ha)(%BA)

10.77 (36.75%) 4.80 BA : Basal area Total EE SS PgPg Stand Characteristics Before After Mean Standard deviation( ±) Mean Standard deviation( ±)

27

4.4 Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was divided into 3 stages.

The first stage consisted in an analysis of mortality at the stand level. A mixed

linear model was built in order to identify effects of deposit, stand type and treatment, and their interactions. Pairs of plots were included as random factors. To examine interactions, the normal distribution of the data was verified and a paired t-test was used to check for the existence of significant difference between the mortality rate in thinned and unthinned plots.

The second stage refers to the ForestGALES model evaluation. First, a

correlation study relating the observed losses and the uprooting or breakage critical wind speed was performed. Secondly, the uprooting critical wind speed was included in a multiple regression with the regional mean wind speed and the topographic exposure (Topex). The regional mean wind speed was obtained from the Canadian Wind Energy Atlas (http://www.windatlas.ca) which was converted by Environment Canada from a height of 30 to 10 meters with the aim to match data readily available from weather stations.

This model was developed by the UK forestry commission to estimate the critical wind speed required to uproot or break trees under relatively homogeneous conditions and single-storied and even-aged stands (Byrne and Mitchell 2012). ForestGALES uses the relationship between the drag of the air on a surface and the aerodynamic roughness of the surface. It is then possible to obtain the total energy from the wind transferred to the forest canopy and consequently the resultant moment applied at the base of the tree (Gardiner et al. 2000, Achim et al. 2005a, Elie and Ruel 2005). The model predicts the windthrow probability as a function of the wind, stand and site characteristics. The windiness is specified by the detailed aspect method of scoring (DAMS). This method describes the site exposure including wind climate and topography. DAMS scores range from 7 (e.g. sheltered valley bottom) to 29 (e.g. exposed mountain top). Input stand data include species, stocking, top height and mean diameter of trees. Finally, the main variables that represent the soil type were those that directly affect the overturning risk as the cultivation and drainage (Hale et al. 2004).

In the present study, stand characteristics were summarized in an adapted version of the ForestGALES model (Ruel 2000). Species specific relationships were included, based on a number of winching studies (Ruel et al. 2000, Achim et al. 2005b, Elie and Ruel 2005, Bergeron et al. 2009). For thinned plots, stand data from pure stands after thinning were used. This model allows for the calculation of the critical wind speed that can break or uproot a tree, considering all criteria related to the species, soil type, silviculture, and drainage conditions. On the other hand, since the wind exposure component (DAMS) of the model has not been fully adapted for eastern Canada, Topex-to-distance and mean regional wind speed were used to characterize the wind component.

Several authors indicate a good correlation between mean wind speed and the topographic features (Busby 1965, Ruel et al. 1996, Quine and White 1997). The Topex (topographic exposure) is an index that incorporates the wind exposure into the windthrow hazard classification (Miller 1985). Topex is calculated as the sum of the angle to the horizon in the eight cardinal directions (Wilson 1984). As a result, the sum can also take positive or negative values. A routine enabling the calculation of Topex within a finite distance has been built by Ruel et al. (2002). The Topex values were calculated with this routine by the Forest Inventory Unit of the Quebec Ministry of Natural Resources.

The third stage involved modeling the probability of mortality at the tree level

through mixed logistic regressions, including the random effect of the pair of plots. Logistic regression has been extensively used for binomial data (Wang and Puterman 1998). The variable response can here be either alive (Y = 0) or dead (Y = 1). The logistic regressions were conducted using the lme4 package of R statistical package (R Development Core Team 2009).

The independent variables were divided into three categories. The first category consists of the original stand characteristics, represented by the data collected in the field, such as age, diameter at breast height (DBH), dominant height, stem density and basal area. The second category includes the parameters associated with the treatment itself: control vs. thinning, thinning intensity, ratio of mean diameter after treatment vs. before treatment. Finally, the third category includes the site variables such as topography, and soil type.

29 Prior to testing the regression models, the colinearity between variables was examined. For the numeric variables, the Pearson correlation test was performed and, for categorical variables, a contingency table analysis was conducted. For the model selection, the Akaike information criterion corrected for small samples (AICc) was used. Thirteen models were considered, based on the researcher knowledge and the literature reviewed (Mazerolle 2006).

In addition, we proceeded to check the Cook‟s distance and verified the existence of outliers (Chatterjee and Hadi 1986, Williams 1987). Then, because of the absence of a formal test for random effect logistic regressions, a contingency table analysis was performed, to verify the goodness fit of the model by comparing the predicted values to the observed values.

31

5 RESULTS

5.1 Mortality analysis at the stand level

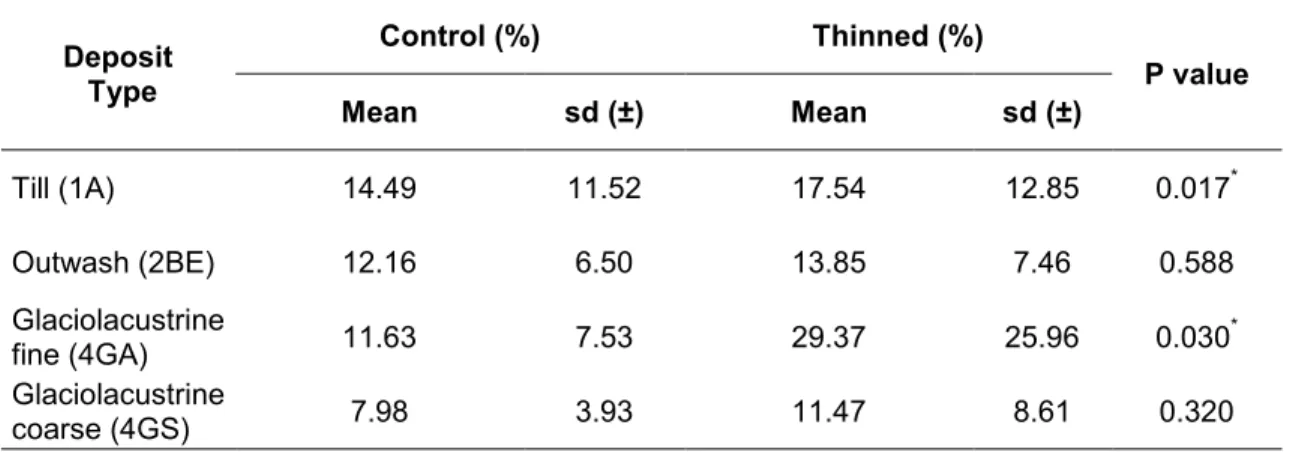

Table 4 presents the results of the mixed linear model looking at mortality at the stand level. The treatment reference level was the control plots (TE). Estimates of stand and deposit type were respectively calculated in reference with EE and till deposit (1A). The negative values indicates that the percentage of losses were lower than the reference level. The treatment presented a p-value of 0.06694 which is close to significance. This tendency translates a higher mortality after thinning in black spruce stands (table 5). Mortality on deposit 4GS was lower than on till (Tables 4 and 6). The interaction between “treatment: stand type” and “treatment vs deposit type” reported only “treatment TR : deposit 4GA” as significant. On deposit till, mortality only slightly increased after thinning whereas mortality more than doubled on deposit 4GA.

Value p-value Intercept 14.75 0.00 Stand PgPg 4.37 0.30 Stand SS -4.35 0.33 Treatment TR 6.06 0.07 Deposit 2BE -5.71 0.19 Deposit 4GA -7.58 0.31 Deposit 4GS -11.46 0.03 Stand PgPg : treatment TR -3.88 0.46 Stand SS : treatment TR -4.35 0.44 treatment TR: deposit 2BE -1.28 0.81 treatment TR: deposit 4GA 53.57 0.00 treatment TR: deposit 4GS -1.40 0.83

Stand Type Control (%) Thinned (%) P value Mean sd (±) Mean sd (±) EE 12.24 10.79 21.80 21.40 0.005* PgPg 12.65 9.20 14.90 10.48 0.282 SS 7.02 5.68 10.39 9.22 0.096 α = 5% Deposit Type Control (%) Thinned (%) P value Mean sd (±) Mean sd (±) Till (1A) 14.49 11.52 17.54 12.85 0.017* Outwash (2BE) 12.16 6.50 13.85 7.46 0.588 Glaciolacustrine fine (4GA) 11.63 7.53 29.37 25.96 0.030 * Glaciolacustrine coarse (4GS) 7.98 3.93 11.47 8.61 0.320 α = 5%

Table 6. Mortality rate in basal area by stand type Table 5. Mortality rate in basal area by deposit type

fir-33

5.2 Predicting mortality at the stand level with the

ForestGALES model

The critical wind speed was obtained using the ForestGales model. Jack pine results are not presented because the model produced critical wind speeds that were unrealistically low. Hence, only black spruce and balsam fir are presented. The critical wind speed for these two species was higher in the control plots than in the thinned plots. Critical wind speeds for uprooting were lower for balsam fir than for spruce but the reverse occurred for breakage (Table 7).

The correlation analysis relating the observed losses and the uprooting critical wind speed showed a coefficient of -0.28 (P<0.001) for black spruce and -0.03 (p=0.813) for balsam fir. Uprooting critical wind speed could only explain 7.6% (R2=0.076) of the variance in mortality for black spruce and 0.1% (R2=0.001) for balsam fir.

The critical wind speed results were submitted to a multiple regression for the two species (black spruce and balsam fir). The variables included in the equation were: Topex, regional mean speed, uprooting critical wind speed.

Table 7. Critical wind speed obtained from ForestGALES model -black spruce and balsam fir-

Main species Plots Uprooting (m/s) Breakage (m/s)

Control 26.84 23.01 Thinned 22.87 19.75 Control 18.00 25.04 Thinned 15.46 22.90 Balsam fir Black spruce

Black spruce

The multiple regressions indicated the regional mean speed as not significant. The Topex and uprooting critical wind speed coefficients were negative, which denote that mortality diminished as these variables increased (Table 8). Figure 3 illustrates the relationships between mortality and the significant variables. An important scatter around the regression line can be seen.

Coefficients Estimate Std.Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 41.640 7.636 5.453 2.51e-07 ***

Topex -0.251 0.110 -2.286 0.024 *

Uprootig critical wind

speed -0.944 0.321 -3.118 0.002 **

signif.codes: '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0,05

R2 =0.1128

p-value= 0.0005297 Table 8 Multiple regression statistics – Black spruce

Figure 3. Correlation between (a) topex, (b) uprooting critical wind speed and mortality rate.

35

Balsam Fir

The multiple regression showed that none of the variables were significant (table 9).

Table 9. Multiple regression statistics - Balsam fir

Coefficients Estimate Std.Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 3.464 14.605 0.237 0.814

Topex 0.071 0.078 0.912 0.367

Regional mean speed 1.832 4.476 0.409 0.685

Uprootig critical wind

speed -0.007 0.582 -0.012 0.990

signif.codes: '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0,05

R2 =0.02376

p-value= 0.8134

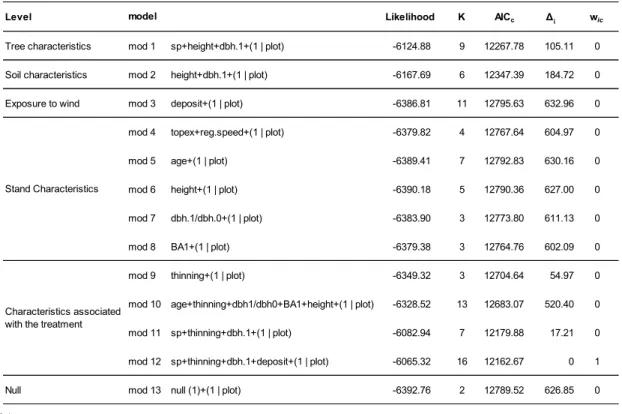

5.3 Predicting mortality at the tree level

The models were designed according to different groups of variables such as tree, soil, wind, and stand variables (Table 10). These models were calculated by mixed logistic regression including the random effect of the pair of plots. The best-performing model was number 12 (AICc = 12162.67; Wic = 1). This model has a Δ¡=0, that represents the lowest value among all the models. An Akaike weight equal to 1 indicates that it has a 100% chance of being the best model from the set of candidates (Mazerolle 2006). The model includes variables associated with tree and soil characteristics and the thinning effect. Likewise, the hierarchical organization of the models shows that the addition of certain variables improves the quality of the model; e.g. model 11 that includes the variable species, thinning rate and DBH after thinning, resulted to be a good candidate taking the second place with an AICc of 12179.88 but adding the deposit effect increases the performance of the model. Finally the Model 12 is adequately fitted with the observed data since it was able to correctly classify 84.5% of cases.

Codes

sp : Species

dbh.1 : Diameter at breast height after thinning dbh.1/dbh.0 : Relation dbh after and before thinning BA1 : Basal area after thinning

5.3.1 Thinning rate and windthrow probabilities

On the most abundant deposit type (till), the probability of mortality increases with thinning intensity. In control plots (thinning =0%) the stands are only submitted to the natural mortality and the probability of mortality will change according to site and stands characteristics. Indeed, the model reported that the trees most susceptible to die were those with small DBH, which means that there exists an inverse relationship between the probability of mortality and DBH. Comparing the three most representative species, the effect of DBH is similar but the model showed that jack pine was the most likely to die whereas black spruce and balsam fir showed relatively similar probabilities (Figure 4).

Table 10. Hierarchy of models obtained using the AIC

Level Likelihood K AICc Δ¡ wic

Tree characteristics mod 1 sp+height+dbh.1+(1 | plot) -6124.88 9 12267.78 105.11 0 Soil characteristics mod 2 height+dbh.1+(1 | plot) -6167.69 6 12347.39 184.72 0 Exposure to wind mod 3 deposit+(1 | plot) -6386.81 11 12795.63 632.96 0 mod 4 topex+reg.speed+(1 | plot) -6379.82 4 12767.64 604.97 0

mod 5 age+(1 | plot) -6389.41 7 12792.83 630.16 0

mod 6 height+(1 | plot) -6390.18 5 12790.36 627.00 0 mod 7 dbh.1/dbh.0+(1 | plot) -6383.90 3 12773.80 611.13 0

mod 8 BA1+(1 | plot) -6379.38 3 12764.76 602.09 0

mod 9 thinning+(1 | plot) -6349.32 3 12704.64 54.97 0 mod 10 age+thinning+dbh1/dbh0+BA1+height+(1 | plot) -6328.52 13 12683.07 520.40 0 mod 11 sp+thinning+dbh.1+(1 | plot) -6082.94 7 12179.88 17.21 0 mod 12 sp+thinning+dbh.1+deposit+(1 | plot) -6065.32 16 12162.67 0 1

Null mod 13 null (1)+(1 | plot) -6392.76 2 12789.52 626.85 0

model

Stand Characteristics

Characteristics associated with the treatment

37

Figure 4. Probability of mortality by species according to thinning intensity on a till deposit.

5.3.2 Deposit type and mortality

According to the best model (i.e. number 12), the probability of mortality varies with deposit type but the effect of this variable is smaller than the effect of species. The increased probability of mortality with DBH and with thinning intensity occurs across all deposit types. Similarly, jack pine is the most likely to die on all deposit types (Figures5, 6, and 7).

Mortality varies with deposit types. The glaciolacustrine-4GA end up being the most vulnerable type of deposit followed closely by the till deposit. Glaciolacustrine-4GS type results as the least vulnerable to mortality.

P rob a bi lity of wi nd throw DBH (cm)

Figure 6. Probability of mortality in lightly thinned plots (25%) according to major deposit types

39

Figure 7. Probability of mortality in heavily thinned plots (50%) according to major

41

6 DISCUSSION

Initially, the planned treatment was a thinning from below - defined as the activity of tree removal primarily from lower canopy, such as suppressed trees and those among the smaller diameter classes (Kerr and Haufe 2011). On the contrary, the mean DBH was reduced by 1.2 cm immediately after treatment, which shows the application of a thinning from above. Although, regulations from 1997 recommended that the relation between DBH after and before thinning should be greater than 1.05, our results showed a ratio of 0.9. With reference to the difference between thinning from above and from below, Cremer et al. (1982) pointed out that it would be preferable to use the thinning from below to reach a more favourable Height/DBH relation of the remnant trees; on the other hand (Busby 1965) considers more effective the thinning from above because it removes the tallest trees, which are associated with higher bending moments.

Schelhaas et al. (2007) mentioned that, in stands of low density, less competition occurs between the individuals, so individual trees would be more stable. Basal area is considered as a good indicator to measure the competition between trees (Bertrand and Bolghari 1970). The regulations of the Ministry of Natural Resources in 1997 (MRNFP 2003) stated that there should be between 23 and 33 m2/ha of basal area before the treatment. The mean basal area in our study was 39.5 m2/ha with a standard deviation of 10.5 m2/ha. Moreover, the mean basal area of spruce and fir stands surpassed the limit advised by the Ministry, mainly with values of 42.9 m2/ha for spruce and 41.8 m2/ha for fir; only the pine stands were within the range prescribed, with a mean value of 29.3 m2/ha. These excessive densities involved a high competition level and could partly explain greater losses in basal area for spruce (21.8%) compared with pine (14.90%). Balsam fir reported 10.39% of mortality in thinned plots. Although this species is considered one of the most vulnerable to windthrow, it ends up being the least affected. These results confirm the importance of an appropriate stand selection to reduce mortality and reach the silvicultural goals of the treatment. Several studies regarding this issue arrive to this same conclusion (Bertrand and Bolghari 1970, Ruel 1995, Prégent 1998, Tremblay and Laflèche 2012). The Ministry regulations also advice the importance to consider the stand age indicating that thinning must be executed at least 15 years before the stand maturity. However, at the beginning of this study 69% of

spruce, 73% of pine and 44% of fir stands had reached or exceeded the optimum rotation age (Tremblay and Laflèche 2012).

One of the expected benefits of a commercial thinning is to reduce the natural mortality by removing trees most likely to die naturally (MRNFP 2003). However, it is widely known that the windthrow hazard is greater during the next two to five years after thinning (Busby 1965, Cremer et al. 1982, Savill 1983). This increase finds its explanation in the increased wind speed after thinning and the reduction of the capacity to dissipate the wind energy between the trees (Cremer et al. 1982, Ruel 1995). Trees can acclimate to winds blowing relatively constantly, while exceptionally strong winds can cause damage such as the breaking of branches or uprooting of trees (Salisbury and Ross 1969, Nicoll and Ray 1995). Busby (1965) explains that trees need up to 15 years to become adapted to the stand structure changes. So, during this adjustment period, wind enters more easily into the forest stands and this translates into a higher mechanical stress on the roots (Nicoll and Dunn 2000, Ruel et al. 2003b, Tarroux et al. 2010). Likewise, Tarroux et al (2010) and Elie and Ruel (2005) reported that in high density stands a great resistance exists due to the interlocking root system. Our study showed a tendency for higher mortality at the stand level 10 years after thinning and a significant increase at the tree level. The fact that stands were initially old and very dense probably aggravated the effects of thinning.

Inter-species variations in susceptibility to windthrow can be examined at two levels. At the stand level, pure jack pine stands experienced no increase in mortality after thinning relative to control stands. Jack pine is considered as one of the least vulnerable coniferous species to windthrow in this region because of its deep rooting abilities and its strong anchoring capacities (Rudolph and Laidly 1990). Burns and Honkala (1990) explain that windthrow is not a serious problem to jack pine except in the shallow soils or when more than 1/3 of its basal area has been thinned. Black spruce and balsam fir are widely known for having a shallow root system which makes them more susceptible to the windthrow hazard (Frank 1990, Elie and Ruel 2005). Additionally, balsam fir is considered as one of the species most vulnerable to overturning, because it is susceptible to stump and root decay. In high density stands, balsam fir is more susceptible to windthrow because of a poor root development (Ruel 2000). In our case, a significant increase in mortality at the stand level was observed for black spruce stands but not for balsam fir stands. Noteworthy the fir stand where

43 identified as the youngest stands in our study which could explain the overall low mortality and the absence of increased mortality after thinning.

At the individual stem level, our results showed a strong impact of species. Jack pine was identified as the species with the highest probability of mortality. This seems to contradict observations at the stand level. This can be explained by the fact that the increased probability of mortality occurred in small stems. In general, there is a lower presence of jack pine trees of small diameter in comparison with black spruce stands, because of its lower shade tolerance (Burns and Honkala 1990). Hence, the greater probability of mortality applied to a small number of stems does not lead to higher losses at the stand level. Species relative vulnerability can also vary according to soil type. Elie and Ruel (2005) found that the root characteristics of black spruce, which are not dependent of the deposit thickness, make it well adapted to shallow soils whereas rooting of jack pine is better developed on deep soils where it is able to develop a tap root. However, Mergen (1954) mentions that the tap root by itself does not necessarily imply wind stability, explaining that a tree of 30m height needs a 3m tap root to support the strength of the wind.

Many factors are involved in tree‟s mortality rate. The windthrow is not the unique potential cause in trees mortality; several studies refer to advanced decay, Infections and spread of root rot in the stand as influential in mortality rate (Putz et al. 1983, Wallentin and Nilsson 2012). These factors could have played a significant role here, given the advanced age of the treated stands. Temperature has also an impact in the mortality rate (Lines et al. 2010), an increase in temperature, combined with higher wind speed after thinning, conducing to water stress (Van Mantgem et al. 2009). In our case, the advanced age and high initial stand density probably meant that residual trees probably had poorly developed crown and root systems. This would be particularly true for small trees that experienced the most mortality.

The results from the mortality analysis at the stand level showed stand type and treatment as not significant. Some effects of deposit type were noted, either as single effects or in interaction. Deriving conclusions on deposit effects however must be made with caution here since confounded effects of stand type and deposit type can be present. In fact the triple interaction treatment*stand type*deposit type could not be tested because too many combinations were poorly represented. Glaciolacustrine-4GA