The Contribution of Word Stress and Vowel Reduction to the Intelligibility of the Speech of Canadian French Second Language Learners of English

Thèse Andrée Lepage Doctorat en Linguistique Philosophiae Doctor (Ph.D.) Québec, Canada © Andrée Lepage, 2015

RÉSUMÉ

Cette thèse porte sur la perception par des locuteurs natifs de l’anglais (L1) de la production orale de francophones parlant l’anglais comme langue seconde (L2). Elle emploie une méthode d’analyse mixte visant à déterminer: (1) l’existence d’une interférence et (2) le degré d’interférence de l’accent tonique et de la réduction vocalique avec l’intelligibilité ; (3) la comparaison de l’impact de l’omission de la réduction vocalique et de son mauvais positionnement sur l’intelligibilité; (4) si un déplacement de l’accent vers la droite nuit d’avantage à l’intelligibilité qu’un déplacement vers la gauche; (5) si les locuteurs anglophones familiers avec l’accent francophone comprennent plus aisément l’anglais des locuteurs francophones.

Nous avons administré un test de perception de type ‘close-shadowing’, composé de 80 mots anglais multisyllabiques prononcés par des Québécois, à 60 anglophones L1. Les mots étaient classés selon les erreurs prosodiques les plus fréquentes. Trente des participants anglophones avaient été rarement ou jamais exposés à un accent francophone L2 (groupe non tolérant). Trente étaient en contact quotidiennement avec le français ou avec des locuteurs francophones de l’anglais L2 (groupe tolérant). Les réponses fournies par les anglophones étaient analysées qualitativement afin de déterminer quelles erreurs prosodiques contribuaient le plus à la perte d’intelligibilité. La mesure du temps de réaction des participants a permis d’évaluer l’effet de ralentissement des différents types d’erreur sur l’identification des mots.

Les résultats montrent que la réduction vocalique nuit davantage à l’intelligibilité que le mauvais positionnement de l’accent et que l’omission de la réduction vocalique nuit moins que son mauvais positionnement. Un déplacement de l’accent lexical à droite nuit d’avantage à l'intelligibilité qu’un déplacement vers la gauche. Le groupe tolérant a identifié plus de mots que le groupe non tolérant, ce qui suggère que l’auditeur natif tire profit pour la compréhension de la production orale L2 de l’exposition à une L2. Néanmoins, les temps de réponse étaient statistiquement similaires chez les deux groupes. Cela pourrait s’expliquer par le fait que les auditeurs tolérants à l’accent connaissent aussi

le français, et activeraient plusieurs candidats lexicaux pendant la recherche de l’unité lexicale appropriée, ce qui ralentirait leur temps de réaction.

ABSTRACT

This thesis studies the perception of French accented English by native English speakers. It presents the results of a mixed methods study aimed at exploring (1) whether both incorrect word stress and incorrect vowel reduction have an impact on intelligibility, (2) if so, whether they interfere equally, (3) whether the omission of vowel reduction has a greater or lesser impact on intelligibility than misplacement, (4) whether rightward misplacement of word stress has a greater impact on intelligibility than leftward misplacement, and (5) whether L2 speech that typically misproduces word stress and vowel reduction is more intelligible to listeners who are familiar with the accent.

Sixty native Canadian English listeners performed a close-shadowing task whereby they evaluated 80 Canadian French (CF) accented two-, three- and four-syllable words categorized according to the naturally occurring prosodic errors they contain. Thirty native English judges had had little or no exposure to CF L2 speech (i.e., are non-accent-tolerant) and 30 use, or are in daily contact with French and/or French-accented English (i.e., are accent-tolerant). The judges’ responses were analysed qualitatively to determine which prosodic error contribute to loss of intelligibility, and quantitatively to determine which errors slow word identification.

Results show that both incorrect stress and vowel reduction interfere with an L2 speaker’s intelligibility (Research Question 1) but they do so unequally. Incorrect vowel reduction is more detrimental (Research Question 2). Results also show that omitting vowel reduction is less detrimental to intelligibility than misplacing it (Research Question 3). As for stress, intelligibility is more impaired by rightward than leftward misplacement (Research Question 4). As for accent familiarity, the accent tolerant group accurately identified more words than the non-accent-tolerant group, suggesting that exposure to a particular L2 does benefit a listener (Research Question 5), though the response times for both listener groups were statistically similar. A possible explanation for these mixed results is that the accent-tolerant listeners, because they speak French, activate more lexical candidates during lexical access, thus slowing down their reaction times.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

RÉSUMÉ ... iii

ABSTRACT ... v

TABLE OF CONTENTS... vii

LIST OF FIGURES ... xi

LIST OF TABLES ... xiii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... xv

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

CHAPTER 2 PHONOLOGICAL AND PHONETIC THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 11

2.1 Metrical Phonology ... 11

2.1.1 Metrical theory and the general properties of stress ... 12

2.1.2 The prosodic hierarchy ... 13

2.1.3 Parameters and parameter settings ... 19

2.1.4 English and French parameter settings ... 23

2. 2 Phonetic manifestations of word stress in French and English ... 30

CHAPTER 3 PERCEPTUAL PROCESSING: THE MERGE MODEL ... 35

3.1 Misconceptions about speech and its perception ... 35

3.2 Prosody in speech perception ... 38

3.3 The Merge model ... 40

3.3.1 Crucial features of the Merge model ... 40

3.3.2 Merge: The general architecture... 52

CHAPTER 4 LITERATURE REVIEW: THE CONTEXT OF THE STUDY ... 57

4.1 Definitions of intelligibility ... 57

4.2 The contribution of suprasegmentals versus segmentals to L2 intelligibility ... 59

4.3 The influence of familiarity on intelligibility... 76

4.4 Summary ... 88

CHAPTER 5 THE STUDY ... 89

5.1 Research Questions ... 89

5.2 Research Design ... 89

5.3 Context for the Study... 91

5.4 Participants ... 93

5.4.2 Native English Speakers ... 96

5.5 Word Production Task for test Design – Phase I ... 99

5.5.1 Materials ... 99

5.5.2 Procedure ... 102

5.6 Data Analysis for Phase I ... 105

5.6.1 Perceptual analysis – Transcription ... 105

5.6.2 Instrumental analysis ... 106

5.7 Perception test – Phase II ... 108

5.7.1 Materials ... 108

5.7.2 Procedure ... 108

5.8 Data Analysis for Phase II ... 110

5.8.1 Qualitative analysis ... 110

5.8.2 Quantitative analysis ... 110

CHAPTER 6 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ... 113

6.1 Preliminary analyses ... 113

6.1.1 Qualitative analyses ... 114

6.1.2 Quantitative analyses and mean estimates ... 114

6.1.3 Descriptive analysis ... 116

6.2 Global statistical analyses and discussion of research questions on the impact of incorrect prosodic errors on perception of L2 intelligibility ... 119

6.2.1 RQ1 – Do both incorrect word stress and incorrect vowel reduction have an impact on intelligibility? ... 126

6.2.2 RQ2 - Do incorrect word stress and incorrect vowel reduction impact intelligibility equally? ... 128

6.2.3 RQ3 - Does omission of vowel reduction impact intelligibility more or less than misplacement? ... 134

6.2.4 RQ4 - Does rightward misplacement of word stress have a greater impact on intelligibility than leftward misplacement of word stress? ... 139

6.3. Descriptive and Statistical analyses comparing accent-tolerant and non-accent tolerant listeners ... 142

6.3.1. Descriptive analysis ... 143

6.3.2. Results of statistical analyses and discussion ... 151

CHAPTER 7 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION ... 159

7.1 Theoretical implications ... 161

7.1.2 L2 teaching and research ... 164

7.2 Limitations of the present study and suggestions for further research ... 167

REFERENCES ... 171 APPENDIX A ... 197 APPENDIX B ... 199 APPENDIX C ... 200 APPENDIX D ... 203 APPENDIX E ... 204 APPENDIX F ... 205 APPENDIX G ... 207 APPENDIX H ... 208 APPENDIX I ... 211 APPENDIX J ... 212 APPENDIX K ... 215 APPENDIX L ... 216 APPENDIX M ... 219 APPENDIX N ... 220

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 3.1 The Merge model (McQueen, Cutler, & Norris, 2000) ... 53

Figure 5.1 Diagram of the research design ... 92

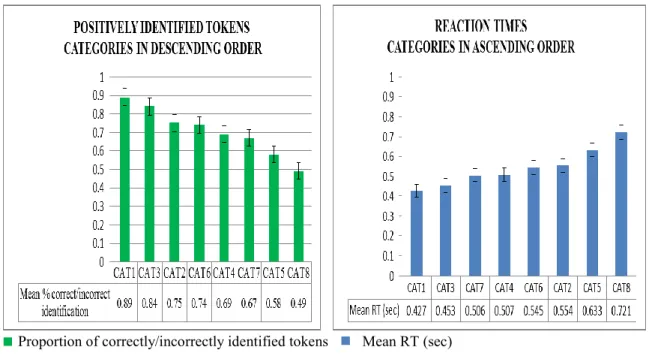

Figure 6.1 Positively identified tokens and RTs per category ... 116

Figure 6.2 The ordering of categories by proportional and mean results ... 118

Figure 6.3 Ordering categories by statistical differences ... 124

Figure 6.4 Ordering categories by statistical differences ... 129

Figure 6.5 Ordering categories by statistical differences ... 132

Figure 6.6 Ordering categories by statistical differences ... 136

Figure 6.7 Ordering categories by statistical differences ... 140

Figure 6.8 The descriptive statistical mean results of positively identified tokens and RTs per category for the accent-tolerant and non-accent-tolerant groups. ... 144

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1 Phonetic cues to stress in English and French ... 33

Table 4.1 Summary of Studies of Segments and Suprasegmentals to Intelligibility (following discussion order) ... 77

Table 5.1 Biographical information of the L2 learners ... 95

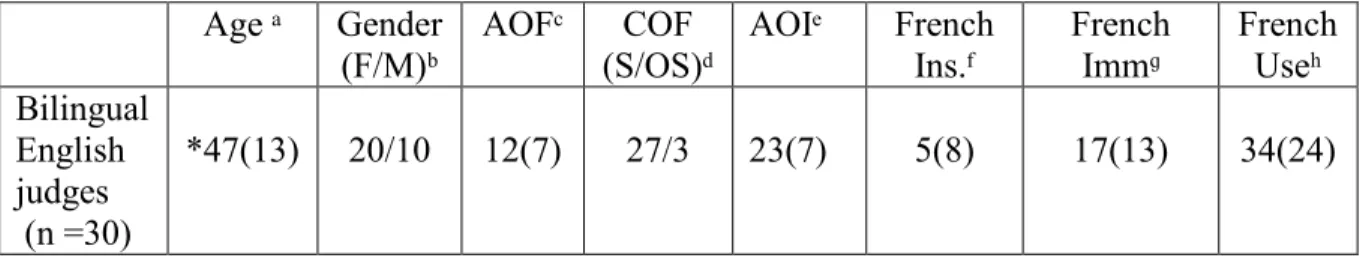

Table 5.2 Biographical information of the accent-tolerant group ... 97

Table 5.3 Biographical information of the non-accent-tolerant (i.e., monolingual) English judges .. 98

Table 5.4 Natural word stress and vowel reduction errors found in CF-accented English ... 107

Table 6.1 Ordering of categories by proportion of positive identification and mean RTs ... 117

Table 6.2 Manova test results of global effect of category on both dependent variables ... 120

Table 6.3 Manova test results of global effect of category on each dependent variable ... 120

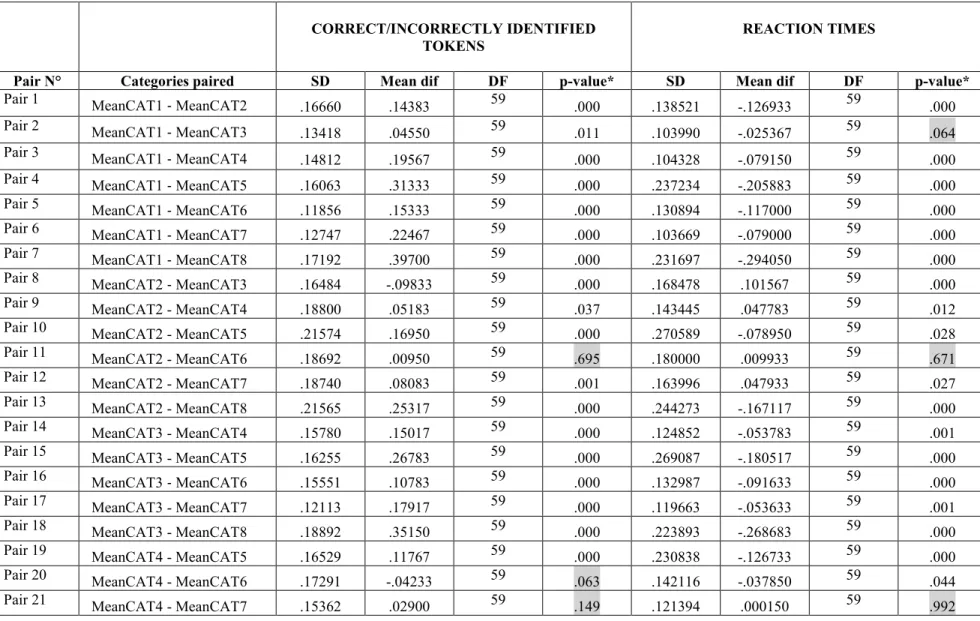

Table 6.4 Results of MANOVA comparison test on the repeated factor 'category' of correctly identified token and RT pairing ... 121

Table 6.5 The comparison test results for pairs that are not statistically different ... 125

Table 6.6 The comparison test results for positively identified data ... 131

Table 6.7 The comparison test results for CAT5 and CAT8 for the positively identified and RT data ... 134

Table 6.8 Mean positively identified token results from the comparison tests ... 136

Table 6.9 Mean RT results from the comparison tests ... 138

Table 6.10 Mean positively identified tokens results from the comparison test ... 140

Table 6.11 Mean RT results from the comparison test ... 142

Table 6.12 Ordering of categories by proportion of positively identified tokens for each group .... 145

Table 6.13 Comparison between the global category ordering results and those obtained for the non-accent-tolerant group ... 146

Table 6.14 Comparison between the global category ordering results and those obtained for the accent-tolerant group ... 147

Table 6.15 Ordering of categories by mean proportion of positively identified tokens for each group ... 148

Table 6.16 Ordering of categories by mean RTs for each group ... 149

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

When I started my academic career I had no idea it would end with a Phd. Life just happened. Throughout this process I have been able to reflect on all the support and encouragement I have received from various sources. I would like to take this opportunity to thank them. During this process, many told me that I was courageous to pursue a Phd. Honestly, I think there is a fine line between courage and stupidity, and during this process I felt many times like I had crossed that line. My running joke was that Phd stood for Permanent-Head-Damage. Now that the process is at its end, I truly appreciate all those who encouraged me to keep focused on my academic path.

I would like to express my deep appreciation and gratitude to my Phd supervisor, Dr Darlene LaCharité, for her critical spirit, sharp mind, and thoughtful guidance in helping me to conceptualize and carry out this research. I sincerely thank you for all the hours you have devoted to this project and for your patience in reviewing this dissertation. You have been a life-changing force and have given me the best learning experience of my life. My sincere gratitude also goes to the two other members of my board, Dr. Shahrzad Saif and Dr Johanna-Pascale Roy. Throughout this process they generously gave their time, expertise, and encouraging words when needed. Without their support, this work would not have been possible.

I am indebted to many other people for their comments, advice and participation. I would like to thank Daniel Stoltzfus for being my second transcriber. Anglophones with a good phonetic transcription background are hard to find in Quebec City, so he was a gem. A very special thanks goes to the ESL students and Native English speakers who participated in this research project. I would also like to thank my friends for understanding why I have been anti-social for the past number of years, or always visited them with a computer and hours of work to do. I promise to be back to my old social self soon.

Last but not least, I want to thank the members of my family. First my mother, who has always been a strong role model for me as an independent, achievement orientated woman. Through this process she always provided me with support, soft words and unconditional

love and understanding of my craziness. You have always been my idol I hope my endeavor will have a similar effect on my girls. Second, I want to thank a special person who I consider not only a sister-in-law but a friend. She was one of my very few proofreaders and provided a supportive ear when needed. Last, I want to thank my girls for encouraging their mother to better herself and also telling me how much they are proud of me.

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

Looking over the history and relative importance of pronunciation and research in second language (henceforth L2) teaching in the 20th century provides a glimpse at how a

pendulum of beliefs and practices can swing from one extreme to another (Levis, 2005). In the first half of the 20th century, approaches such as the reformed method, audiolingualism,

and the silent method established pronunciation as a major concern of L2 instruction (Celce-Murcia, Brinton, & Goodwin, 1996; Derwing, 2010; Levis, 2005; Setter, 2008). The importance given to the teaching of pronunciation was driven by the nativeness principle, which posits that "it is both possible and desirable to achieve native-like pronunciation in a foreign language" (Levis, 2005: 370).

Into the mid-20th century, the pendulum of opinion on the importance that pronunciation

had in language teaching was swinging to the other extreme where it remained for the rest of that century. As of the 1960s and 70s, at the same time as English was expanding its foothold as a world lingua franca (Jenkins, 2000, 2002), the teaching of pronunciation in language classrooms had drastically declined (Breitkreutz, Derwing, & Rossiter, 2009; Celce-Murcia et al., 1996; Derwing, 2010; Derwing & Rossiter, 2003; Jenkins, 2000, 2002, 2006; Levis, 2005). The loss of popularity of pronunciation teaching was due mainly to research findings that suggested biological constraints on L2 attainment, and that recognized that native-like competence was an unrealistic goal for post-pubescent learners (Chomsky, 1965). In short, non-native speakers (NNS) will always have an accent.

One of the major factors that contribute to an L2 accent is the interlanguage system NNSs develop (Flege & Davidian, 1984; Flege & Port, 1981; Gass & Selinker, 1993; Macken & Ferguson, 1981; Selinker, 1972; among others). The L2 learner’s interlanguage system is separate linguistic system that has not, and may never, become fully proficient but that is approximating the target language. As argued by Tarone (2005: 486), the interlanguage system reflects neither the speaker’s L1 nor L2, but rather is "a system with its own formal rules of phonology, morphology, syntax, lexicon, and discourse patterns." Manifestations of the development of the interlanguage system that can be observed are L2 speakers substituting some L2 features with those of their L1, i.e., language transfer,

overgeneralizing target language rules (e.g., making irregular verb forms fit regular patterns - *falled) or creating innovations, among other things (Selinker, 1972; Tarone, 2005; Tremblay & Owens, 2010). The development of an interlanguage system for a L2 learner is systematic, i.e., rule-governed, and common to all learners, any difference being explicable by differences in their learning experience (Selinker, 1972).

Influenced by transformational-generative grammar (Chomsky, 1959, 1965) and cognitive psychology (Neisser, 1967), which viewed language as rule-governed behaviour, or system, rather than habit formation, L2 teaching became focused on grammatical structure and words, and not on speaking skills. But, as argued by Setter (2008), it is rather pointless to study a living foreign language if one does not intend to communicate in it with other speakers of that language. Indeed, with globalization, there was a growing need for L2 speakers to be able to not only read and write in L2, but also to communicate orally (Derwing, 2010). In the latter part of the 20th century, around the 1980s, a new approach

called the communicative approach took hold, and is still currently dominant in L2 teaching today (Celce-Murcia et al. 1996; Derwing, 2010; Liao & Zhao, 2012). The focus of this approach is communication and not form (e.g., pronunciation, formal syntax, etc.) (Celce-Murcia et al. 1996; Hadley, 2001; Harlow & Muyskens, 1994; Pennington & Richards, 1986; Savignon, 1991; Tschirner, 1996).

Under the communicative approach, teachers and students alike believed - as some still do - that L2 speakers can improve their accents just by being extensively exposed to the target language. However, research has shown that this is not necessarily so (Altmann, 2006; Altmann & Vogel, 2002; Elliot, 1997; Macdonald, Yule, & Powers, 1994; Peperkamp & Dupoux, 2002; Tremblay & Owens, 2010). For one thing, the input that a student receives is not necessarily 'good input', even in a classroom setting. Globally, over 80% of the world’s ESL/FL teachers are NNSs (Canagarajah, 1999). Although these teachers should be modeling accurate pronunciation, it is not always the case (Breitkreutz et al., 2009; Derwing, 2010).

Another reason why relying on only natural input to improve an accent is not as effective as believed is due to the sounds we hear being distorted through what is referred to as our

L1-language filter. Our L1 experience produces a L1-language-specific perceptual filter through which all language is perceived (Cutler, 2012ab; Grenon, 2010; Kuhl, 2000). The language-specific filter alters the dimensions of speech we attend to. In the course of learning our L1, our brains are taught to attend to certain features in the speech stream that are important to our L1 and to disregard those that are not; what we perceive is often not what we really hear (ibid). Once formed, language filters make learning a L2 much more difficult because the neural mapping appropriate for one's primary language is different from that required by other languages. Turning back to our discussion on the importance of pronunciation teaching in the end of the 20th century, due to the students being left to their own devices

and not being corrected on form, the result was that their accented speech was riddled with transfer and inter-language errors that obscured intelligibility and comprehensibility.

Although accentness, intelligibility and comprehensibility are related terms that are sometimes used interchangeably in the literature, they have distinct meanings.

Accentedness is a listener’s judgment of how much a speaker’s speech differs from an

expected production pattern (Derwing, 2010; Derwing & Munro, 1997, 2005; Munro, 2011; Munro & Derwing, 1995b). Intelligibility refers not to a judgement but to the extent to

which the acoustic-phonetic content of the words generated by the speaker is phonologically recognizable (intelligible) to a listener (Field, 2005; Hustad, 2012; Jenkins, 2000, 2002; Kent, Weismer, Kent, & Rosenbek, 1989; Kirkpatrick, Deterding & Wong, 2008; Smith & Nelson, 1985). In other words, intelligibility is when the listener’s interpretation of the phonetic signal matches the speaker’s intention – at the word level.

Comprehensibility is the listener’s ability to recognize the meaning of the word or utterance

in its given context (Smith & Nelson, 1985). In short, intelligibility, which is the focus of this thesis, is at the word level and comprehensibility is generally at the sentence level. With respect to L2 pronunciation, the current thinking is that L2 speech has to be intelligible and comprehensible but not native-like (Jenkins 2000, 2002, 2006; Derwing, 2010; Levis, 2005; Levis & Grant, 2003). There is currently a consensus that ''…there is nothing wrong with having an accent…'' (Derwing, 2010: 33). However, the intelligibility of English is a particular concern because English has become firmly entrenched as the language of international communication, commerce and trade, politics, science and

diplomacy. There are more L2 speakers of English than L1 speakers of English, and the great majority, if not all, of these L2 English speakers speak with an accent (Crystal, 2003; Jenkins, 2000, 2002, 2006; Johnson, 2009; Modiano, 2001; Setter, 2008; Yano, 2001) that they are unlikely to shed. The goal of L2 English speakers today is not accent reduction, but intelligibility (Jenkins, 2000; 2002, 2006). However, the particular aspects of English L2 speech that render a speaker (un)intelligible to the listener are still a matter of research and some debate, as will be discussed in more detail in chapter 4.

It is often assumed that the level of accentedness is directly related to a NNS’s perceived intelligibility; however, studies have shown that this is not entirely true (Derwing & Munro, 1997, 2009; Munro & Derwing, 1995, 1999). For example, L2 English speakers’ tendency to substitute phonemes in the L2 with those in their L1 due to the speaker’s L1 phoneme inventory lacking a native counterpart for a given L2 sound (e.g., replacing the English interdental fricatives /θ/ and /ð/ with /t/ - /d/, /s/ - /z/, or /f/ - /v/), does not usually make L2 English speakers’ speech unintelligible (Derwing, 2010).

However, certain aspects of L2 accented speech can render it unintelligible. It has been shown that incorrect production of a language’s prosodic features contributes more to lack of intelligibility than does incorrect production of segmental features (Altmann, 2006; Anderson-Hsieh & Koehler, 1988; Anderson-Hsieh, Johnson, & Koehler, 1992; Bond, 2008; Bond & Small, 1983; Cutler and Clifton, 1984; Derwing & Munro, 2005; Field, 2005; Hahn, 2004; Kijak, 2009; Slowiaczek, 1990; Trofimovich & Baker, 2006; Zielinski, 2008). Prosody is a complex speech domain that is a "combination of tonal, temporal, and dynamic features associated with such suprasegmental aspects of phonology as stress, rhythm, and intonation" (Trofimovich & Baker, 2006: 2), as will be discussed in more detail in chapter 2.

In most languages, prosodic structure is realized by the variations in patterns of the acoustic features fundamental frequency (f0), duration and amplitude of the vowel. In some languages, such as English, segmental quality (including vowel reduction) can be used in concert with adjustments to fundamental frequency, duration, amplitude, etc. to signal stress, stress contrast, and the language’s rhythm (Beckman, 1986; Fry, 1958; Kim,

Broersma & Cho, 2012; Ladefoged, 1993; Lehiste, 1970; MacKay, 1987; Martin, 1996; Schwartz, 2010, 2015; Shattuck-Hufnagel & Turk, 1996; Tremblay, 2007, 2008ab, 2009; Tremblay & Owens, 2010; Ueyama, 2012; White & Mattys, 2007), as will be discussed in depth in chapter 2. On the production side, all languages have available to them the same phonetic properties (i.e., fundamental frequency, duration and amplitude) to give salience to a particular syllable in a word (Cutler, 1986, 2005; Dupoux, Sebastian-Gallés, Navarete & Peperkamp, 2008; Fry, 1958; Grosjean & Gee, 1987; Ladefoged, 1993; Lehiste 1970; Tremblay, 2007; Tyler & Cutler, 2009), however, the precise employment may not be the same. For instance, in English stress is accompanied by rises in pitch whereas in other languages it may be accompanied by a fall in pitch (Cutler, 2012; Fry, 1958). On the perception side, even when two or more cues are employed, one can be employed more reliably therefore listeners may attend to the reliable cue(s) and less so, or not at all, to other cues that may co-occur (Cutler, 2012; Cutler, Mehler, Norris & Segui, 1987; Kijak, 2009; Otake, Hatano, Cutler & Mehler, 1993; Peperkamp, Dupoux & Sebastian-Gallés, 1999; Schwartz, 2010, 2015; Tyler& Cutler, 2009; Van Donselaar, Koster & Cutler, 2005, just to name a few). For instance, English listeners rely more on pitch change, even though stressed syllables are generally longer in duration (Fry, 1958; MacKay, 1987). In short, listening is language-specific. The perception of listeners will be further discussed in Chapter 3.

Despite the recognition that correct production of prosody has an important impact on the intelligibility of L2 speech, little research has been devoted to the acquisition of prosody in L2 learning (Altmann, 2006; Busà, 2008; Lukyanchenko, Idsardi & Jiang, 2011; Rasier, Caspers & van Heuven, 2010; Schwartz, 2010, 2015; Tremblay, 2007; Tremblay & Owens, 2010; Ueyama, 2012; White & Matty, 2007). Even less attention has been paid to the L2 acquisition of word stress (also referred to as lexical stress), which did not become the topic of psycholinguistic research until quite recently (Altmann, 2006; Huart, 2002; Kijak, 2009; Lukyanchenko et al., 2011; Schwartz, 2010, 2015; Tremblay, 2007, 2008ab, 2009; Tremblay & Owens, 2010; White & Mattys, 2007). One problem with studying word stress in English is that the phonetic processes of stress and vowel reduction occur in concert (Beckman, 1986; Fry, 1958; Ladefoged, 1993; Lehiste, 1970; MacKay, 1987; Martin, 1996). In English, the rhythmic stress pattern is dependent on not only stressed syllables

but also on unstressed syllables (Schwartz, 2010) (see Chapter 2 for an in-depth discussion and comparison of the phonological and phonetic aspects of word stress in English and French). Both prosodic aspects have been argued to help L1 English listeners identify spoken words (Braun, Lemhöfer & Mani, 2011; Capliez, 2011; Cooper, Cutler & Wales, 2002; Fear, Cutler & Butterfield, 1995; Huart, 2002; Schwartz, 2010; Tremblay, 2009; Trofimovich & Baker, 2006), but which aspect is most responsible for L2 intelligibility, or whether it is the two in concert, is as yet unclear (see Chapter 4 for discussion of studies on word stress and vowel reduction). Nonetheless, research such as that by Altmann (2006) argues that the acquisition of word stress is an important component of L2 acquisition because incorrect production of word stress in L2 can "precipitate false recognition [of words], often in defiance of segmental evidence" (Cutler, 1984: 80) and may lead to miscommunication or even communication breakdown. As illustrated by the anecdotes below and as amply supported by research (Busà, 2008; Diana, 2010; Huart, 2002; McNerney & Mendelsohn, 1992; Mennen, 2006), incorrect prosody can render a L2 speaker’s speech misleading, if not totally unintelligible. Consider the following four exchanges, each of which took place between a native English speaker and an English as a second language (ESL) speaker.

(1) Examples (from personal experience and observation) of communication breakdown due to inaccurate stress and vowel reduction.

a. A Canadian French (CF) speaker, an onboard attendant on a train, informed his service manager that there was an inVAlid ([ɪnvǽlɪd]) passenger on board. The service manager, a native English speaker, understood the problem to be that the passenger had no valid ticket for travel. In fact, the problem was that the passenger needed a wheelchair, i.e., was an INvalid ([ɪ́nvəlɪd]).

b. A CF speaker in an English class, introducing himself, said that he drove a CEment ([símənt]) truck. After a moment of confusion the instructor laughed, having understood him to say that he drove a SEmen, rather than a ceMENT, truck ([səmɛ́nt]).

c. In an introductory linguistics class, the professor, a native English speaker was teaching morphology. The professor had just explained the notion of bound stems, using, astronaut as an example, and asked for other words that could justify treating astronaut as being made up of two morphemes, astro- and -naut. One CF student offered the word astroNOmy [æstɹonómi]. Only after several repetitions did the professor recognize the intended word.

d. A Japanese ESL visitor to Canada, looking for the street she called NiaGAra [na͜͜͜͜͜͜͜͜͜͜ijəgáɹa], stopped to ask an English speaking resident of the neighbourhood, a professor specializing in L2 phonetics and phonology, for directions. The native English speaker responded that she was sorry, but she did not know that street, only to realize later that the visitor was looking for NiAgara ([na͜͜͜͜͜͜͜ijǽgɹə]) Street, only two blocks from her own home.

In each of these cases, the speaker’s pronunciation involved a word stress error, which, for native English listeners seems to have a particularly deleterious effect on the intelligibility of words (see Chapter 2 for an in-depth discussion) even in the context of a grammatically correct sentence (Kennedy, 2013).

It is not just listeners who have negative experiences resulting from lack of intelligibility. This comment from a CF speaker of ESL gives voice to a common complaint.

"Whenever I spoke to an Anglophone, they kept saying to me "What?" or "Can you repeat that, please?" I would repeat my sentence or word again and again. Finally they would say "Oh!" and repeat my sentence or word, using my exact words. It was so maddening. I know my words and grammar are good, but they pretended as if not understand me, just because of my French accent."

Experiences such as the ones exemplified by our anecdotes are common for CF L2 speakers, due to the CF L2 speakers transferring the prosodic characteristics of French onto English. Incorrect word stress placement and vowel reduction are characteristic of naturally produced CF L2 English speech (Tremblay & Owens, 2010).

Although French speakers of L2 English are the ideal language group to study to settle the debate over whether word stress or vowel reduction, or both in concert, interfere with intelligibility they are certainly not the only L2 speaker group to make word stress errors when they speak English. Many L2 English speakers of other languages such as Polish, (Schwartz, 2010, 2015), Finnish, Czech, Arabic, Turkish, Hungarian (Kijak, 2009; Peperkamp, 2004; Peperkamp & Dupoux, 2002), just to name a few that have fixed-stress placement and/or do not reduce vowels in unstressed syllables, tend to make the same prosodic errors when speaking English.Hence, defining which prosodic error(s) contributes more to the intelligibly of English L2 speech would benefit ESL teachers, as it will inform them as to what areas to emphasize during their teaching.

With globalization and immigration, more and more people, especially in big cities, are in frequent contact with NNSs of English (Derwing, 2010; Jenkins, 2000, 2002, 2006). Because of immigration and students coming from abroad to study, classrooms in English speaking countries have seen an important rise in the number of students whose mother tongue is not English (Setter, 2008). For example, according to Statistics Canada (CANSIM: 447-0044), in 2007, 15% of the student population in the English speaking provinces of Canada, consisted of people whose mother tongue was not English; by 2013 that number had doubled (30%) and it is still growing. Most, if not all, of these people speak with an accent, which generally includes NN production of prosody, so intelligibility is an issue of increasing concern.

The fact that, globally, people are more exposed to accented English speech raises the issue of whether listeners will become more habituated to accented speech because it is more common. As previously mentioned, studies have shown that exposure to a target language does not necessarily improve a L2 speaker’s production, but does it improve a listener’s perception? Do we really get used to an accent, so that intelligibility is no longer an issue when listening to a particular accent? The existing research has produced mixed results (see Chapter four for a review of studies on accent tolerance). Hence, one of the goals of this thesis is to determine if the perceived intelligibility of a speaker is advantaged by a listener’s exposure to accented speech.

If pronunciation, especially prosody, is so important to the intelligibility of L2 speech, why are L2 speakers not specifically taught English prosody, notably word stress in L2 classrooms? To sum up the reasons presented so far in this chapter, first, due to the rise of generative linguistics and the recognition that post-pubescent learners cannot realistically hope to achieve nativelike production, pronunciation was pushed to the wayside (Derwing & Munro, 2005). In most L2 classrooms, pronunciation is not taught at all. Second, the recognition of the need for intelligibility is fairly recent (Derwing, 2010; Field, 2005; Jenkins, 2000, 2002; Tremblay, 2007, 2008ab, 2009; Zielinski, 2006, 2008; just to name a few) so the need to teach it has not yet had a chance to shape activities in the L2 classroom. The last factor that contributes to the lack of pronunciation teaching, and which is one of the driving forces of this study, is that research lacks a clear answer as to whether it is word

stress or vowel reduction, or the combination of both, that interferes most with the intelligibility of L2 English speakers (see Chapter 4 for review of the literature). The precise impact of incorrectly produced word stress on intelligibility needs considerably more study, both with respect to its extent and how it functions to impair intelligibility. Practical research will help instructors to determine which aspects are important to focus on in order to improve L2 intelligibility (Derwing, 2010). Hence, this thesis is intended as a contribution to the body of research that seeks to determine if it is word stress or vowel reduction, or both in concert, that interfere with L2 English speaker’s intelligibility.

This dissertation has adopted a mixed-method approach to investigate the impact that incorrect word stress and incorrect vowel reduction have on the intelligibility of CF L2 English speech. The literature suggests that CF L2 English speakers produce a range of prosodic errors that will allow us to test which particular errors, or error combinations, are most deleterious to intelligibility. Studying naturally occurring errors, and error combinations, provides a closer to real-life situation that listeners are confronted with. This study also seeks to establish whether exposure to the L2 contributes to the perception of L2 intelligibility. This research project aims to shed new light on the questions left unanswered by previous studies by employing both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. The specific research questions of the present study are given in (1).

(1) Research questions

RQ.1. Do both incorrect word stress and incorrect vowel reduction have an impact on intelligibility?

RQ.2. If so, do they interfere equally with intelligibility?

RQ.3. Does the omission of vowel reduction have a greater or lesser impact on intelligibility than its misplacement?

RQ.4. Does rightward misplacement of word stress have a greater impact on intelligibility than leftward misplacement of word stress?

RQ.5. Is L2 speech that typically misproduces word stress and vowel reduction more intelligible to listeners who are familiar with the particular accent?

This thesis contains seven chapters. The rest of this thesis is organized as follows: Chapter 2 introduces the theoretical framework that forms the basis for this study with respect to phonology and phonetics. This chapter is divided into two main sections. The first section deals with the phonological aspect of stress placement. Within this section, the first subsection outlines the architecture of the theory of Metrical Phonology (Halle & Vergnaud, 1987; Hayes, 1995; McCarthy & Prince, 1996ab); Nespor & Vogel, 2007; Selkirk, 1984). The second subsection discusses parametric constraints (Archibald, 1993; Dresher & Kaye, 1990; Hayes, 1980) that affect prosodic structure, more specifically stress placement, cross-linguistically. The last subsection presents the different parametric settings of English and French and how they affect stress placement in the two languages. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the phonetic aspects of stress as it pertains to English and French.

Chapter 3 presents the theoretical framework that forms the basis for this study with respect to speech processing. In the first part of the chapter we look at some aspects of continuous speech that an effective speech processing model has to account for. The first section of the chapter provides an overview of the complexity of processing speech, notably some misconceptions often associated with speech perception. This is followed by a brief summary of the importance that prosody has in speech processing. In the second part of Chapter 3 we present how the Merge model (McQueen, Cutler, & Norris, 2000), the speech processing model adapted for this study, avoids the misconceptions about speech processing, and how it deals with prosody, in contrast to four other popular models of speech perception. This is followed by a summary that provides a more detailed description of the architecture of the Merge model and the reasons for which we chose this model. The methodology for the study is presented in Chapter 5. The statistical results, our interpretation of those results and some of their implications for speech processing are presented in Chapter 6. Chapter 7 presents a brief summary and conclusion.

CHAPTER 2 PHONOLOGICAL AND PHONETIC

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Listening to connected speech is a task that humans perform effortlessly each day. The effortlessness is surprising given the short time that the brain’s processing system has to manage different types of information. To recognize words, the acoustic speech signal simultaneously carries information about segmental phonemes (i.e., consonants and vowels) and suprasegmental phonological information (i.e., pitch, amplitude, duration variations that may instantiate stress differences, voice quality, spectral slope, etc.), both types of which must be accessed and coordinated with syntactic, semantic, pragmatic and contextual information within milliseconds.

This chapter discusses the phonological and phonetic framework within which this study is couched. The first section deals with the phonological aspect of stress placement. Within this section, the first subsection outlines the architecture of metrical phonology theory, also known as metrical theory. The second subsection discusses parametric constraints that affect the prosodic structure, more specifically stress placement, in languages. The last subsection presents how the different parametric settings of English and French affect stress placement. The second section concludes the chapter with a discussion of the phonetic aspects of stress as it pertains to English and French.

2.1 Metrical Phonology

The theory of metrical phonology seeks to account for the assignment of stress and delimit the different types of stress systems that occur cross-linguistically. We follow Selkirk (1984), Nespor and Vogel (2007), McCarthy and Prince (1996), Halle and Vergnaud (1987), and Hayes (1995), as they are the main developers of this theory. Metrical theory does not treat stress as a segmental feature as Sound Pattern of English (Chomsky & Halle, 1968) did but as a property of higher-order units such as syllables and feet. This will be discussed in more detail below.

2.1.1 Metrical theory and the general properties of stress

One claim of metrical theory is that stress, or prominence, is a relational property. Accordingly, such prominence can only be established by comparing it to an equal opposing entity in the same domain (Fox, 2000; Hayes, 1995; Keating, 2006; Ladefoged, 1993; Lehiste, 1970). For example, a stressed syllable is recognizable as such only in relation to the co-occurrence of an unstressed syllable in the same word (to be refined below). Similarly, a higher tone is recognizable as such only in relation to the co-occurrence of a lower one in the same sequence. Word prominence in a sentence can only be established in relation to other words that are not as prominent in the same sentence. Linguistically speaking, the absolute values are seldom, if ever, important; however, the relative value or degree of prominence of an item is significant.

Variations in stress lend speech its recognizable melodic properties, also known as the prosodic structure of a language. Sound units are shortened or lengthened in speech in accordance with an underlying patterning that defines a language’s rhythmic properties. The information gleaned from melody, timing and stress in speech (prosody) is said to aid the intelligibility of spoken message by enabling the listener to easily segment continuous speech into phrases and words (Cutler & Norris, 1988; Cutler & Otake, 1994; Cutler, Mehler, Norris, & Segui, 1986; Mehler, Dommergues, Frauenfelder, & Segui, 1981; Otake, Hatano, Cutler, & Mehler, 1993). Prosody includes the elements shown in (1) (Keating, 2006:119).

(1) Elements of prosody

a) Phrasing: This refers to the various size groupings of smaller domains into larger ones, such as segments into syllables, syllables into words, or words into phrases. b) Word stress: This refers to the prominence of syllables at the word level.

c) Accent: This refers to prominence at the phrase level and the distribution of tones (pitch events) associated with any of these, such as lexical tones associated with syllables, or intonational tones associated with phrases or accents.

Each of these aspects of prosody is achieved using three phonetic features: fundamental frequency (f0) (perceived as pitch), amplitude (perceived as loudness) and duration (perceived as length) (Lehiste, 1970; Shattuck-Hufnagel & Turk, 1996). These phonetic correlates of prosody are referred to as suprasegmental cues, since they are usually associated with linguistic elements that are considered above the segment (i.e., syllables, words, phrases, or even entire utterances) (Fox, 2000; Keating, 2006; MacKay, 1987; Shattuck-Hufnagel & Turk, 1996).

2.1.2 The prosodic hierarchy

The suprasegmental organization of language is represented by a prosodic hierarchy (Halle & Vergnaud, 1987; Hayes, 1995; McCarthy & Prince, 1996; Nespor & Vogel, 2007; Selkirk, 1984). Each of the units represents a well-defined domain in which specific phonological processes apply. Below in (2) is the illustration of the prosodic hierarchy. (2) The Prosodic Hierarchy (Selkirk, 1980, 1984; Nespor & Vogel, 1986, 2007; Hayes,

1989, 1995)

Prosodic Domain Example

Utt John said he lived in Canada.

IP (Intonational Phrase) he lived in Canada

PP (Phonological Phrase) in Canada PW (Prosodic Word) Canada

Ft (Foot) Cana

σ (Syllable) Ca

μ (Mora) a

Represented in (2) is a prosodic hierarchy composed of seven levels (there are some models with eight) (Goldsmith, 1990; Hayes, 1995; Selkirk, 1996). This dissertation focuses on only three of these constituents: the syllable, the foot, and the prosodic word. The focus will be mainly on the metrical foot as it is the domain of timing or rhythm (Halle &

Vergnaud, 1987; Hayes, 1995; McCarthy & Prince, 1996; Nespor & Vogel, 2007; Selkirk, 1984).

The prosodic hierarchy is thought to reflect the organization, in the mind of speakers, of different levels of stress. Stress differs from other phonological properties, such as the featural properties of segments, both in its phonetics and in its phonological organization. Phonetically, phonemes can be physically identified via spectrograms for example, by measuring their formant values, such as for vowels, or by their manner and place of articulation. If formants are altered, notably if the relationship between the formants of a vowel is altered, a different vowel is heard; if place and/or manner of articulation is altered, a different consonant is produced.

Phonologically, phonemes have defined featural properties that help to identify and classify them and that are widely considered to be abstractions of phonetic properties of speech sounds. For example, the phoneme /i/ as in the word beat has the featural properties of [+high], [+front], [+tense]. If one feature is changed, say [+tense] goes to [-tense] then the quality of the vowel also changes – it becomes the phoneme /ɪ/ as in the word bit. Stress is unusual in that it has no invariant physical correlates; rather, it is an abstract property that is instantiated physically by a combination of phonetic cues, the selection and combination of which differ somewhat across languages. Phonologically speaking, stress is distinguished from other phonological elements by the properties of culminativity, rhythmic distribution, gradience and resistance to assimilation (Cutler, 2005; Gussenhoven, 2001; Halle & Vergnaud, 1987; Hayes, 1995; Kijak, 2009; Liberman & Prince, 1977). Each of these properties is discussed in turn.

Culminativity identifies one particular unit (i.e., syllable) in a domain (foot, prosodic word, phrase) from other units of the same type in the same domain and assigns it primary stress (Cutler, 2005; Gussenhoven, 2001; Halle & Vergnaud, 1987; Hayes, 1995; Kager, 2007; Kijak, 2009; Liberman & Prince, 1977; Nespor & Vogel, 2007). This is the stress peak within the unit. The stress peak, the most prominent syllable in its grammatical domain, typically serves as the anchoring point for intonational contours (cf. Kager, 2007). At the word level, in some languages, polysyllabic words may have numerous stressed syllables

but only one will carry main or primary stress. What this implies is that primary stress is not fixed in these languages as primary stress placement is dependent on the number of stressed syllables in a word. Many languages, including English, impose culminativity on content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, or adverbs) and exempt grammatical words (articles, pronouns, prepositions, etc.), which are prosodically dependent on content words (e.g., part of the prosodic word) (Hayes, 1995; Kager, 2007; McCarthy & Prince, 1996). Although culminativity appears to be cross-linguistic, the domain in which it applies may differ from language to language (Cutler, 2005; Dell, 2000; Halle & Vergnaud, 1987; Hayes, 1995; Nespor & Vogel, 2007). In English, for example, stress is culminative at the word level (every content word has a single strongest stressed syllable), at the level of the intonational phrase, and possibly at other levels as well, such as the phonological phrase (Cutler, 2005; Halle & Vergnaud, 1987; Hayes, 1995; Nespor & Vogel, 2007; Riad, 2012). In contrast, in French, stress is culminative at the phrase level only (Dell, 2000; Hayes, 1995).

At this point we find it important to distinguish between the culminative function of stress, which we have just discussed, and what is called the demarcative function of stress. Demarcative stress is fixed to a particular syllable within a word. It is not used to give a stressed syllable special status in relation to other syllables. Demarcative stress is used to signal the beginning and/or end of a word boundary directly (if located at a word edge) or its vicinity (e.g., if located on the penultimate syllable). Again, one syllable within a polysyllabic word is the location of this fixed stress. Fixed placement of stress implies that stress cannot be contrastive, i.e., is not used to distinguish one word from another (Cutler, 2005; Gussenhoven, 2001; Kijak, 2009).

As argued by Cutler (2005), the properties of culminative and demarcative stress are potentially important in perception. If stress can distinguish between words, listeners may use cues to stress in identifying spoken words, but if stress cannot help in this way then there is no reason for listeners to use it in word recognition. Similarly, if stress can signal word boundaries, listeners may use stress cues for segmenting continuous speech into

words, but if stress were to have no systematic relation to position within the word, it could not be of use in segmentation.

The property of rhythmic distribution reflects the fact that there is a recurrent temporal pattern to syllable durations and stresses (Hayes, 1995; Selkirk, 1984; Vaissière, 1991, 2005). In some languages, syllables are roughly of equal duration (i.e., isosyllabicity or syllable-timed), whereas in other languages stressed syllables occur at roughly equal intervals (i.e., isochrony or stress-timed). The rhythmic system of languages results from a set of parameter constraints. The particular rhythm system of a language is the result of the settings chosen by the language for each parameter constraint (a point that will be discussed in detail in section 2.1.3).

With respect to the gradience of stress, in stress timed languages there are often multiple degrees of stress: primary, secondary, tertiary, etc. (Hayes, 1995). In some stress timed languages, the degree of stress can have segmental consequences. For example, in English, primary stressed syllables exhibit various emphatic processes: tense vowels under primary stress are diphthongized, voiceless stops preceding primary stressed vowels are aspirated, etc. (MacKay, 1987).1 On the other hand, unstressed syllables are back-grounded: the

duration is reduced and a vowel in an unstressed syllable is usually, if not always, reduced to schwa (Hayes, 1995).

Stress, or lack of it, never assimilates or spreads. A stressed syllable cannot induce stress on the immediately preceding or following syllable. In contrast, many featural properties that are used to identify segments, such as lip rounding [±round], frontness [±front], or nasality [±nasal], can spread onto surrounding syllables. Metrical theory posits that the phonetic and phonological differences between stress and ordinary features can be best accounted for if one abandons the assumption that stress is a feature. In the identification of segments, such as vowels, for example, stress should not be treated as a segmental feature that pertains specifically to them but more of a phonological process the vowel undergoes (Flemming,

1 Voiceless stops are aspirated at the beginning of a stressed syllable, except after syllable-initial /s/ as in the

1993; Hayes, 1995; Huart, 2002). Hence, "the role of prominence with respect to segmental material is in conditioning the distribution of contrasts" (Flemming, 1993: 15).

As summarized in (3), the organization of prosodic constituents in the Prosodic Hierarchy is subject to four specific constraints on prosodic domination (Selkirk, 1996: 190).

(3) Constraints on Prosodic Domination2

a) Layeredness b) Headedness c) Exhaustivity d) Nonrecursivity

These constraints refer directly to the prosodic hierarchy which is repeated here in (4) for the reader’s convenience.

(4) The Prosodic Hierarchy (Selkirk, 1980, 1984; Nespor & Vogel, 2007; Hayes, 1989)

Prosodic Domain Example

Utt John said he lived in Canada.

IP (Intonational Phrase) he lived in Canada

PP (Phonological Phrase) in Canada PW (Prosodic Word) Canada

Ft (Foot) Cana

σ (Syllable) Ca

μ (Mora) a

The Layeredness constraint (formalized as No Cⁱ dominates a Cʲ, j >) posits that no lower prosodic category in the hierarchy can dominate a higher prosodic category. For example, no syllable can dominate a foot, or a foot cannot dominate a prosodic word. The Headedness constraint (formalized as Any Cⁱ must dominate a Cʲ¯¹) states that any prosodic

2 As will be discussed, some of these constraints are not absolute but are violable under certain conditions.

category must dominate at least one instance of the category immediately below it in the hierarchy. For instance, a prosodic word must dominate a foot and a foot must dominate a syllable.

Exhaustivity (formalized as No Cⁱ immediately dominates a constituent Cʲ, j < i-1) militates against skipping levels; for example no prosodic word can directly dominate a syllable. Lastly, Nonrecursivity (formalized as No Cⁱ immediately dominates Cʲ, j = 1) militates against constituents dominating other constituents on the same level, for instance, no foot can dominate another foot, no prosodic word can dominate another prosodic word.

According to Selkirk (1996), the first two constraints, Layeredness and Headedness, are universal inviolable properties but the third and fourth constraints, Exhaustivity and Nonrecursivity, are violable (see Kager, 1995; McCarthy & Prince, 1993a, 1993b; Prince & Smolensky, 2008 for discussion on Exhaustivity and McCarthy & Prince, 1993a, 1993b for Nonrecursivity). For example, Exhaustivity is violated by extraprosodic syllables, i.e., a syllable is not footed, a structure seen in (5a) and (5b), in which an unstressed syllable in the word is not part of any foot, but is directly dominated by the PW-node (example (5a) from Pierrehumbert & Beckman, 1988: 100, example (5b) from McCarthy & Prince, 1993a: 5); hence, skipping a level in the hierarchy.

(5) Domination of category not immediately below

a. Tomato b. Tatamagouchi

PW PW

FT FT FT

σ σ σ σ σ σ σ σ

µ µ µ µ µ µ µ µ

[to (mato)] [(tata)ma(gouchi)]

The examples in (6a, b) illustrate how Nonrecursivity is also violable with compounding, as in English (ibid).

(6) Recursion of PrWd a. Lighthouse b. Helplessness PW PW PW PW PW PW FT FT FT σ σ σ σ σ µ µ µ µ µ µ µ µ [[light] [house]] [[help] less] ness]

A stress system that allows violations of these widespread, if not universal, constraints is more complex. A stress system that completely abides by the constraints is less complex, and more predictable than one that allows violations.

2.1.3 Parameters and parameter settings

The different rhythmic patterns that one perceives from one language to another stem from a language’s settings for various parameters (Archibald, 1993; Dresher & Kaye, 1990; Hayes, 1980). While many parameters have been proposed, this dissertation will deal exclusively with six basic parameters. These six parameters include Foot Headedness, Quantity-sensitivity, Extrametricality, Foot Directionality, Boundedness, and Word Headedness.3

The prosodic structure of a language plays a crucial role in determining which syllable in a word is stressed, in part because stress is represented at the level of the foot. This brings us to our first parameter, Foot Headedness. Once the metrical feet are formed, one syllable per metrical foot is stressed. Metrical theory is based on a binary unit (Hayes, 1995). The head of the foot is the foot’s most prominent syllable. The headedness parameter determines whether a language has or left-headed feet. Left-headed feet yield trochees and right-headed feet yield iambs. The second parameter, quantity-(in)sensitivity, reflects the role of syllable weight in assigning stress to feet. In phonology, a syllable has an internal structure

3 All definitions and explanations come from Hayes (1995) and Halle & Vergnaud (1987), unless otherwise

consisting of an onset and a rhyme, which is further divided into the nucleus and the coda. The anatomy of a syllable is diagrammed below in (7); C stands for consonant and V for vowel; parentheses indicate optionality.

(7) Internal syllable structure

Syllable (σ) Rhyme

Onset Nucleus (Coda) (C)* V* (C)*

Syllable patterns are most often represented as a string of C and V symbols. The CV syllable, that is, a syllable consisting of just one consonant preceding a vowel, is the universal core syllable; all languages have such a syllable (McCarthy, 1979). However, that is by no means the only syllable type. Natural languages display a wide variety of syllable types. Depending on the language, the onset, the nucleus and the coda may contain more than one element, this is represented in (7) by an asterisk (*). That is, an onset or a coda may contain a consonant cluster and the nucleus may contain a long vowel or a diphthong. Some languages also allow syllables without an onset (e.g., English words: ink [ɪŋk], edge [ɛʤ], eight [et], out [o͜͜͜wt]). Many languages allow syllables to have a coda (e.g., English words: lips [lɪps], asked [æskt], texts [tɛksts]). Any deviation from the CV syllable is added complexity. No matter the level of syllable complexity that a language allows, the one obligatory component is a nucleus (Ladefoged, 1993; McCarthy, 1979; MacKay, 1987). The internal structure of a syllable contributes to what is referred to as syllable weight. In the phonology of some languages, especially with regard to the assignment of stress, the distinction between heavy and light syllables plays an important role (Crystal, 2003; Hayes, 1995; Ladefoged, 1993; McCarthy, 1979). What counts as heavy can vary from language to language (Goldsmith, 1990; Hayes, 1995), though the onset of a syllable does not count towards syllable weight in any language. Syllable weight is measured in morae (Hyman, 1985; McCarthy & Prince, 1996; Hayes, 1989; 1995). A light syllable has one mora and a

heavy syllable has two. A CV syllable is usually counted as a light syllable unless it contains a long vowel or diphthong. In these cases, the CV syllable is considered heavy. In some languages, having a single coda consonant is sufficient to make a syllable heavy, in others it is not (such as in Irish). In those languages that consider CVC syllables heavy, the coda consonant is moraic (Hayes, 1995). In other languages, the coda has to be composed of a cluster of consonants for a syllable to be heavy.

Languages that distinguish between heavy and light syllables for purposes of stress assignment are termed quantity-sensitive. In these languages stress is assigned to a heavy syllable (if present) (i.e., heavy syllables occur in head position of feet). Languages that do not make the distinction between heavy and light syllables are termed quantity-insensitive. In a quantity-insensitive language, feet are built ignoring differences in syllable structure (i.e., any type of syllable can occur in the head position of a foot).

With regards to the third parameter, Extrametricality, Universal Grammar allows languages to have prosodic constituents that are invisible to stress assignment. That is to say, some languages, including English, allow a violation of exhaustivity. Any legitimate prosodic unit (e.g., a syllable, a foot, etc.) can be designated as extrametrical (Hayes, 1995; Kijak, 2009). Extrametricality can apply only at the edges of domains (e.g., end of prosodic word or phrase) so that the extrametrical element is not included in the accentual domain. A consequence that arises from applying extrametricality in creating metrical feet is that it creates an option of placing the primary stress syllable on the second or third syllable from the edge of the word (depending on the headedness of the foot).4 We will see examples of

extrametricality in our upcoming discussion of English.

Once the syllables to be included in metrical feet are known, metrical feet can be constructed. This leads us to our fourth parameter, Foot Directionality. Depending on the language, the construction of metrical feet can begin from the left edge of the word (FT Dir Left) or from the right edge of the word (FT Dir Right). In the case of words that have an even number of syllables, the different directions converge on the same result:

4 Kager (1995) maintains that there are three motivations for positing extrametricality: (i) at word edges, it

avoids foot types that are otherwise rare or unattested; (ii) it seeks to account for the stresslessness of some peripheral syllables, and (iii) it seeks to explain apparent exceptions to the stress rules.

(σσ)(σσ)(σσ). However, in the case of words that have an odd number of syllables, directionality of footing would yield different results as to which syllable remains unfooted – extrametrical (assuming binarity of footing). The result of left-to-right footing is shown in (8a) and right-to-left footing in (8b).

(8) Directionality of footing

a) Left-to-right: the right edge of word has an unfooted syllable (σσ)(σσ)(σσ)σ

b) Right-to-left: the left edge of word has an unfooted syllable σ (σσ)(σσ)(σσ)

The next parameter, Boundedness, determines foot size. Stress systems of the world’s languages can be roughly divided into two categories: bounded (or alternating) and unbounded (or non-alternating) (Halle & Vergnaud, 1987; Hayes, 1995; Selkirk, 1984). Bounded feet contain at most two syllables. After that limit is reached, a new metrical foot is started. In contrast, unbounded feet may contain an indefinite number of syllables (Halle & Vergnaud, 1987; Selkirk, 1984). The only reason a new metrical foot is started is if a heavy syllable is encountered when grouping syllables into metrical feet. Some unbounded languages have one stress per word and no alternating rhythm, allowing long strings of unstressed syllables (Kager, 2007).

The final parameter, Word Headedness, is one of two alignment constraints, the first being foot headedness, which determines whether the head of a foot is a syllable on the left (trochaic pattern) or the syllable on the right (iambic pattern). Word headedness, the second alignment constraint, is concerned with directionality. It determines whether the head of the prosodic word, which is the foot that receives primary stress (cf. the discussion of culminativity), is aligned to the left edge or to the right edge of the prosodic word (Halle & Vergnaud, 1987; Hayes, 1995; Kijak, 2009; Pierrehumbert, 1994, 2012).

A summary of the six basic parameters is given below in (9). (9) Parametric constraints on prosodic constituents

P1: Foot Headedness P2: Quantity Sensitivity P3: Extrametricality P4: Feet Directionality P5: Boundedness P6: Word Headedness

As indicated above, a language chooses a setting for each of these parameters. Some parameters are conceived of as YES/NO options. For example a language can accept (YES) or reject (NO) extrametrical syllables, or quantity sensitivity. Accepting these features makes a system more complex. For example, a language that allows extrametricality is more complex than one that does not. A language that is quantity sensitive is more complex than one that is insensitive. A language can also be more complex because it allows violations, for example, extrametricality occurs under certain conditions. Languages that allow a greater number of active parameters (parameter settings set to ON) are more complex systems; in contrast, languages that allow fewer activated parameters (parameter settings set to OFF) result in simpler systems.

2.1.4 English and French parameter settings

In this subsection the parameter settings for Canadian French and English will be presented.5 In (10) we present a summary of the parameter settings for each of these

languages, followed by a brief discussion of the consequences that these settings have in relation to word stress placement and the role it plays in each language.

5The parameters of stress are the same for British English and North American English (NAE) (Liberman &

Prince, 1977; Zwicky, 1978). Some words are differently stressed in different varieties of English due mainly to the nativization versus retention of foreign stress patterns in one dialect but not the other. For example,

ballet is pronounced [bǽle], with nativized stress, in British English, but [bælé] in NAE. However for our

(10) Parameter settings for English and French (adapted from Pater, 1997: 237, who credits Archibald, 1993; Hayes, 1980; Dresher & Kaye, 1990)6

Parameter English setting French setting

P1: Foot Headedness LEFT RIGHT

P2: Extrametricality ON OFF

P3: Quantity-Sensitivity ON OFF

P4: Directionality R>L N/A

P5: Boundedness ON OFF

P6: Word Headedness RIGHT RIGHT

As previously indicated in the discussion of extrametricality, an ON setting results in increased complexity. The summary above immediately shows that the stress system of English is more complex overall than the stress system for French. For instance, for English the parameter settings for Extrametricality, Quantity- Sensitivity and Boundedness is set to ON, whereas for French they are not. Moreover, the directionality parameter is not applicable to French.

The first parameter in our summary is Foot Headedness. As mentioned, the headedness parameter determines whether a language has right or left-headed feet. The parameter setting for English and French differ insofar as English is set to LEFT and for French it is set to RIGHT. The result of this is that English has a trochaic foot (e.g., Hammond, 1999; Hayes, 1995; Halle & Vergnaud, 1987) and French has an iambic (right-headed) foot, if indeed it has one (Goad & Buckley, 2006; Montreuil, 2002; Selkirk, 1978; Tremblay, 2007, 2008a; Tremblay & Owen, 2010).7 Foot headedness for each of these languages is

illustrated in (11).

6 Hereafter, all definitions come from Pater (1997) and Halle & Vergnaud (1987), unless otherwise indicated. 7 Some researchers argue that French does not have a foot (see Jun & Fougeron, 2000; Mertens, 1993;