HAL Id: tel-01561540

https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01561540

Submitted on 13 Jul 2017

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Performance’ pour les Hôpitaux Français - Design, Mise

en oeuvre, et Evaluation

Shu Jiang

To cite this version:

Shu Jiang. Les Analyses du Premier Programme ’Paiement à la Performance’ pour les Hôpitaux Français - Design, Mise en oeuvre, et Evaluation. Santé publique et épidémiologie. Université Paris-Saclay, 2016. Français. �NNT : 2016SACLS185�. �tel-01561540�

NNT : 2016SACLS185

T

HESE DE

D

OCTORAT

DE

L

’U

NIVERSITE

P

ARIS

-S

ACLAY

ÉCOLE DOCTORALE EDSP

Spécialité de doctorat : Economie de la Santé, Santé Publique

The Analysis of the First Hospital Pay-for-Performance Program in

the French Health Care Context - Design, Implementation and

Evaluation

ParMlle. Shu JIANG

Thèse présentée et soutenue à Paris, le 12 juillet 2016 : Composition du Jury :

Mme Lise Rochaix, PU, HDR, Université Paris I, Rapporteur M. Claude Sicotte, PU, HDR, Université Montréal, Rapporteur Mme. Sabine Ferrand-Nagel, MCF, Université Paris XI, Examinatrice

M. Philippe Aegerter, PU-PH, HDR, Université Paris XII, Examinateur, Président du Jury M. Béatrice Fermon, MCF, Université Paris Dauphine, Examinateur

Titre : Les Analyses du Premier Programme ‘Paiement à la Performance’ pour les Hôpitaux Français - Design, Mise en œuvre, et Evaluation

Mots clés : Paiement à la performance, Hôpital, France, Evaluation de l’impact

Résumé Le programme ‘rémunération à la performance’ (P4P) est, au cours des dernières années, devenu populaire pour les fournisseurs de soins de santé. Contrairement aux régimes de paiement traditionnels de soins de santé mesurés par le volume, il récompense les fournisseurs (individus ou institutions) qui répondent à certaines attentes en matière de la performance en ce qui a trait aux soins de santé de qualité ou de l'efficacité. Son développement à l’étranger a bien connu des avancées, au cours de la dernière décennie, même si les preuves empiriques sont mitigées. En septembre 2012, le gouvernement français a lancé son premier programme national de P4P pour les hôpitaux - Incitations Financières à l'Amélioration de la Qualité (IFAQ). Compaqh-MOS-EHESP a élaboré les principes de cette expérimentation.

L’objectif de cette thèse est d’examiner et d'analyser les controverses autour du P4P, par l’analyse de la conception, de la mise en œuvre et de l'évaluation de l’impact d’IFAQ. Inspirés de programmes étrangers, IFAQ est conçu dans le contexte des soins de santé en France. Le processus de mise en œuvre d’IFAQ inclut la sélection de critères de jugement, la construction de score composite, et la décision des modes de valorisation financiers. L'évaluation de l'impact d’IFAQ est effectuée en comparant un groupe intervention et un groupe de contrôle, tout en tenant compte de l'évolution de la tendance des indicateurs de qualité et de l'effet d'une série de caractéristiques des hôpitaux.

Un cadre d'analyse d’évaluation médico-économique des programmes P4P a également été construit. Enfin, la capacité de transfert du modèle IFAQ a été appréhendée par l’étude de son application potentielle dans un autre contexte, à savoir la Chine.

Title: The Analysis of the First Hospital Pay-for-Performance Program in the French Health Care Context - Design, Implementation and Evaluation

Keywords: Pay-for-performance, Hospital, France, Impact evaluation

Abstract: Pay-for-Performance (P4P) has, in recent years, become a popular remuneration method for health care providers. Unlike traditional health care payment schemes that focus on volume, It rewards providers (individuals or institutions) who meet certain performance expectations with respect to health care quality or efficiency. Internationally, P4P has experienced wide development over the last decade, though empirical evidences are mixed. In September 2012, the French government launched its first national P4P program for hospitals, named Financial Incentives for Quality Improvement (IFAQ). COMPAQH-MOS has developed the principles of this experiment.

The aim of this thesis is to test and to analyse the existing P4P controversies, through the design, implementation and evaluation of IFAQ. Based on previous international programs, a new P4P initiative is designed under the actual French health care context. The implementation process of IFAQ involves selection of quality judgement criteria, construction of scoring method, and decision of financial incentive structures. The impact evaluation of IFAQ is conducted by comparing the treatment and control hospitals’ quality results, while taking into account time trend evolution of quality indicators and the effect from a group of hospital characteristics.

A framework of cost-effectiveness analysis on P4P programs has also been constructed, and the feasibility of transferring P4P into another context, namely China, has been studied by conducting a case study of P4P in the Chinese health care market.

The Analysis of the First Hospital Pay-for-Performance Program

in the French Health Care Context - Design, Implementation and

Evaluation

Doctorate: Shu Jiang

Thesis Director: Prof. Etienne Minvielle ED420, Paris Sud University

Acknowledgement

Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Prof. Etienne Minvielle for the continuous support of my Ph.D. study and research, for his patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. His guidance helped me in all the time of research and writing of this thesis.

Besides my advisor, I would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Prof. Lise Rochaix, Prof. Claude Sicotte, Prof. Sabine Ferrand-Nagel, Prof. Philippe Aegerter, and Prof. Béatrice Fermon, for their helpful and insightful comments, critical and inspirational questions, and all the stimulating advices.

I would like to express my gratitude to colleagues in Compaqh, Romain Rabeux, Aude Fourcade, Stanislas Esposito, Marie Ferrua, Benoit Lalloué, Fatima Yatim, Anne Girault, Guillaume Hebert, Jingyuan Lin, for the stimulating discussions, for the time we were working together, and for all the fun we have had in the last three years and a half. I am grateful to our external expert Carine Milcent and Marc Le Vaillant for their help on the econometrics part of this thesis. Special thanks to Prof. Philippe Loirat, who provided me particularly helpful guidance and support over these years.

Last but not the least, I would like to thank my family: my parents for giving birth to me at the first place and supporting me spiritually throughout my life.

Context Page

Introduction 7

1. Context for the Launch of a French Hospital P4P Initiative 13

1.1 Lack of incentives on quality in the existing remuneration methods 14

1.2 The introduction of P4P in different countries 20

1.3 Empirical controversies of P4P from existing programs 39

1.4 Theoretical aspects of P4P programs 40

1.5 The need for remunerating quality in the current French health care context 47

2. Research Methodology 50

2.1 Literature review on international P4P initiatives 50

2.2 The French program (IFAQ) as a case study 51

3. IFAQ Design and Lessons from International Programs 54

3.1 Design elements of various P4P programs 54

3.2 Empirical pitfalls in P4P implementation 60

3.3 The French experiment: design of IFAQ 62

4. IFAQ Implementation - Principles and Quality Score Calculation 66 4.1 Composite quality score and financial bonus calculation: references from

Value-Based Purchasing program 66

4.2 Guiding principles of the French IFAQ approach 68

4.3 Hospital accreditation and quality indicators development in France 68

4.4 Selection of judgement criteria for IFAQ 71

4.5 Calculation method of IFAQ score 72

5. Impact Evaluation of IFAQ - Methodology, Data and Results 76

5.1 Data description 76

5.2 Methodology of IFAQ evaluation 86

5.3 Policy impact analysis 93

5.4 The association between quality score and hospital characteristics 98

6. Other Impact Analysis of IFAQ 106

6.1 Concept of cost-effectiveness analysis 106

6.2 Measurement of P4P costs 107

6.3 Measurement of P4P outcomes 108

7. The Transplant of P4P into a New Context: Healthcare P4P in China 113

7.1 Background 113

7.2 Structure of Chinese physician payment 114

7.3 Current implementation of P4P in Chinese hospitals and its problems 115

7.4 Some references to China, from international experiences 117

List of Tables, Figures & Appendix

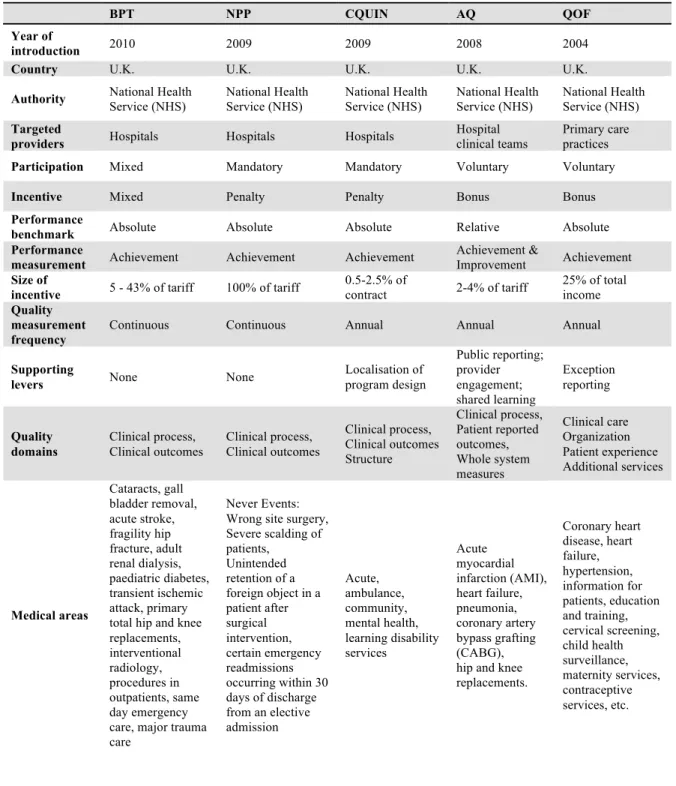

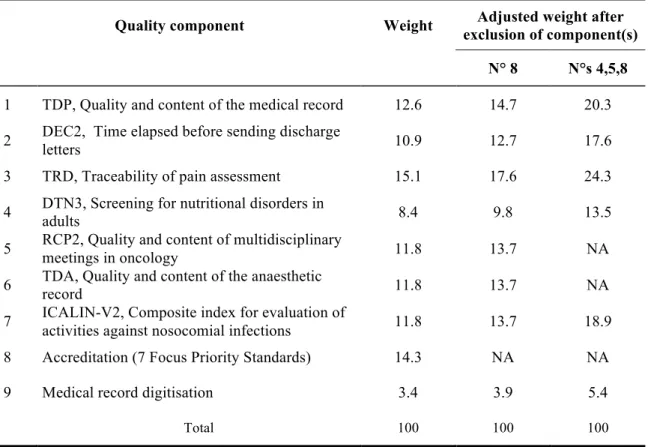

Table 1-1. Pay-for-Performance Programs over the World Table 1-2. Pay-for-Performance Definitions

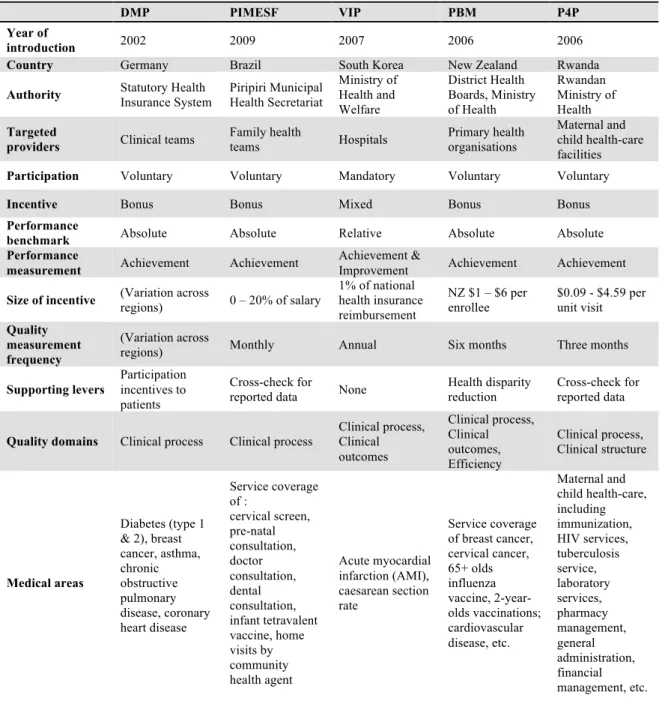

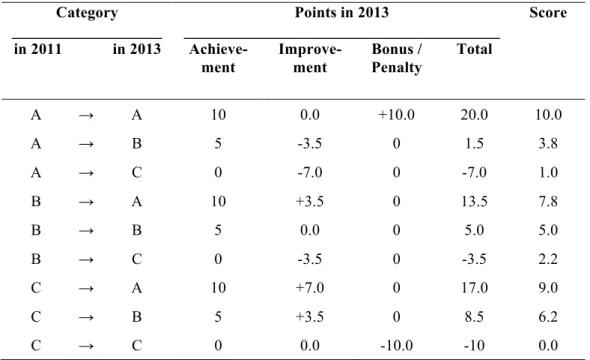

Table 1-3. Quality Domains and Measures in the Value-based Purchasing Program, FY2014 Table 1-4. Weighted Value of Each Domain

Table 1-5. Selected P4P Programs in the World. Key-features Table 3-1. Quality Components of the IFAQ Initiative

Table 4-1. Accreditation Decision Levels

Table 4-2. Method of Calculation of Achievement/Improvement Score Table 4-3. Weights Allocated to Quality Components by Working Group

Table 5-1. Distribution of IFAQ scores and component scores for participants in 2013 (n=426), Overall and by Quartiles

Table 5-2. Normality tests for IFAQ score (426 hospitals)

Table 5-3. Descriptive Characteristics of the participating hospitals (n=426), overall and by four quartiles of the IFAQ score distribution

Table 5-4. Baseline Characteristics of Treatment/Control Group Hospitals Table 5-5. Assignment and Treatment

Table 5-6. Impact Evaluation of IFAQ

Table 5-7. Impact Evaluation of IFAQ (No. of treatment hospitals= 221, No. of control hospitals=1123)

Table 5-8. Regression Estimates (Ordinary least squares and quantile regression estimates of estimated IFAQ score on hospital characteristics)

Table 6-1. Cost-effectiveness Framework for P4P Programs Figure 4-1. Transfer of Numerical Scores to Letters A/B/C Figure 5-1. Selection of Hospitals

Figure 5-2. Histogram of IFAQ score Figure 5-3. Quantiles of IFAQ score

Figure 5-4. Evolution of Quality Indicators and IFAQ Score Appendix 1. References

Appendix 2. A list of all the selected articles in the Literature Review. Appendix 3. Publication 1

Appendix 4. Publication 2 (Submission) Appendix 5. Publication 3

Thesis Summary

Pay-for-Performance (P4P) has, in recent years, become a popular remuneration method for health care providers. It distinguishes itself from the traditional health care payment schemes, namely fee-for-service (FFS), capitation, and diagnosis-related groups, by focusing on the quality, not volume, of health services delivered. It rewards providers (individuals or institutions) who meet certain performance expectations with respect to health care quality or efficiency. Internationally, P4P has experienced wide development over the last decade, such as the Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program for U.S. hospitals and the Quality and Outcome Framework (QOF) for British general practitioners. However, empirical evidences for different existing programs are mixed. Positive effects are limited, especially in the long term.

In September 2012, the French government launched its first national P4P program for hospitals, named Financial Incentives for Quality Improvement (IFAQ). A working group formed by representatives of French Ministry of Health (DGOS), High Authority for Health (HAS), hospitals federations and a research team COMPAQH-MOS has developed the principles of this experiment.

The aim of this thesis is to test and to analyse the above-mentioned P4P controversies, through the design, implementation and evaluation of IFAQ. Based on previous international programs -their common design factors and empirical pitfalls, a new P4P initiative is designed under the actual French health care context. The implementation process of IFAQ involves selection of quality judgement criteria, construction of scoring method, and decision of financial incentive structures. The impact evaluation of IFAQ is conducted by comparing the treatment and control hospitals’ quality results, while taking into account time trend evolution of quality indicators and the effect from a group of hospital characteristics. Throughout these steps, new empirical evidences are collected to confirm or to contradict previous ones, in the process of which contributions are expected to be made also for theoretical aspects.

A framework of cost-effectiveness analysis on P4P programs has also been constructed, synthesized on previous unsystematic studies and for the future analysis of IFAQ. Before the end of this thesis, we study the feasibility of transferring P4P into another context, namely China, by conducting a case study of P4P in the Chinese health care market.

Introduction

Pay-for-Performance (P4P) has, in recent years, become a popular remuneration method for health care providers. It distinguishes itself from the traditional health care payment schemes by focusing on the quality, not volume, of health services delivered. Quality has become an important ingredient in the evaluation of health care systems, alongside cost and access [1]. According to the definition by Research & Development Corporation (RAND), pay-for-performance is the general strategy of promoting quality improvement by rewarding providers (physicians, clinics or hospitals) who meet certain performance expectations with respect to health care quality or efficiency [2].

Some predominant payment systems include fee-for-service (FFS), capitation, and diagnosis-related groups. FFS reimburses providers according to the volume of defined health care items provided. The major drawback of FFS is over-provision of services, which raises health care expenditure. Capitation, on the other hand, limits provider payment to a fixed amount of money on a per capita basis. In contrast to FFS, capitation may cause under-provision of medical services and selection of patients. Neither FFS nor capitation provides incentives for health care quality improvement. Other payment schemes, such as global budget and diagnosis-related groups (DRG) present in a number of countries, bear no target on quality either, as they stimulate hospitals to optimize the volume of care under cost constraints, and payment can stay the same regardless of the quality of services [3]. P4P is thus introduced to emphasize quality of services delivered under this context.

Internationally, P4P has experienced wide development over the last decade. It concerns both individual practitioners and health care organizations. Some major ones include the Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program for U.S. hospitals, the Quality and Outcome Framework (QOF) for British general practitioners, the Contracts to Improve Individual Practice (CAPI) for French general practitioners. However, up until recently, most publicised P4P programs are for individuals, either primary care physicians or specialists; only a minor number are for hospitals, the main example being VBP. Thus it is considered that there is still large room of development for P4P in health care organisations.

Meanwhile, empirical evidences for the existing programs are mixed. Positive effects are limited, especially in the long term. Short term improvements in health care quality are

susceptible to gaming behaviours such as improving documents instead of services delivered, avoiding patients who tend to lower the P4P score, less time and effort dedicated to activities and domains not covered by P4P.

In September 2012, the French government launched its first national P4P program for hospitals, named Financial Incentives for Quality Improvement (IFAQ). The Q standing for ‘Quality’ expresses the will to exclusively focus on the promotion of quality. A working group formed by representatives of French Ministry of Health (DGOS) and High Authority for Health (HAS) hospitals federations and a research team COMPAQH-MOS has developed the principles of this experiment [4]. The COMPAQH project team (Coordination for Measuring Performance and Assuring Quality in Hospitals) is a French national initiative for the development and use of quality indicators, coordinated by the French School of Public Health (EHESP), and more specifically its research laboratory MOS (Management of Health Care Organizations –EA7348).

Under the French health care context, P4P is the last step in the health care quality regulation system. Recent years have been marked by the development and validation of quality indicators (QIs) in France, which makes possible performance measurements in hospitals. The launch of the website ‘Scope’ (http://www.scopesante.fr/) by DGOS and High Authority for Health HAS facilitates the public disclosure of quality indicator scores. Given the two general approaches concerning quality regulation in French hospitals –national accreditation and QI reporting, the need for additional improvement stimulations was recognized by different French authorities, after several years’ public disclosure of hospital performance quality.

The aim of this thesis is to test and to analyse the above-mentioned P4P controversies, through the design, implementation and evaluation of IFAQ. Its design is based on a comprehensive literature review of initiatives previously launched in different countries over the world. Some major programs in the United States, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Brazil and New Zealand are compared and contrasted; their common design factors are retrieved for analysis, as well as empirical pitfalls. Based on these international experiences, in combination with the actual French health care context, a new P4P initiative is designed for quality improvement in French hospitals. The implementation process of this initiative involves different practical issues, including selection of quality judgement criteria, construction of scoring method, and decision of financial incentive structures. This process is conducted in close collaboration with

members from DGOS and HAS, as well as representatives from different hospitals’ federations. The impact evaluation of IFAQ is conducted by comparing the treatment and control hospitals’ quality results, while taking into account time trend evolution of quality indicators and the effect from a group of hospital characteristics. Throughout these steps, new empirical evidences are collected to confirm or to contradict previous ones, in the process of which contributions are expected to be made also for theoretical aspects.

This thesis is structured as the following. After this part of introduction, the first chapter presents the context of our analysis on P4P, the situation that necessitates the introduction of P4P in different countries, as well as in France. Firstly, the existing health care remuneration schemes, namely salary, fee-for-service, global budget, capitation and diagnosis-related groups, though different in their mechanisms, don’t involve any incentives on quality. Secondly, there are various definitions of P4P, provided by different health care organisations, each emphasizing different elements. However, all of them focus on financial incentives on quality. On the other hand, in practice, a variety of P4P initiatives have also been implemented in different countries. Though different in their design elements, all of them aim at health care quality promotion. An overview of these concepts and practices is presented, which is the product of our comprehensive literature review. Thirdly, it is discussed and concluded how, from different theoretical perspectives, economics, sociology, and organizational theory, P4P plays a role in health care quality promotion. However, empirical experiences bring quite a few controversies, which is briefly summarised in the forth part. Fifthly, the need, as well as the feasibility, of remunerating quality in the current French health care context is discussed. The second chapter is devoted to the research methodology issues, which is composed of a comprehensive literature review and the French IFAQ initiative developed as a case study in terms of its design, implementation and evaluation. The statistical and econometrical methods used to the policy impact evaluation are depicted in the fifth chapter. We also precise our specific roles at each step of the IFAQ development.

The next chapter focuses on the design of P4P, the mechanisms of different design elements and empirical pitfalls. P4P programs may differ in their targets (individuals, institutions, physician groups), financial remuneration methods (bonus, penalty, mixed), performance benchmarks (absolute level, relative ranking), performance measurement (achievement, improvement, both), performance aspect (process, outcome), level of incentives, and supporting

levers such as public reporting. Each design element has its pros and cons, which have to be taken into account when designing a new P4P program. Meanwhile, certain empirical pitfalls are difficult to avoid, no matter how delicate the program is designed. Four of them are discussed in this chapter, namely gaming, two-tier market of health service supply and demand, eviction effect. Next, the design of French IFAQ experimentation is discussed, by taking into account the above international lessons.

The fourth chapter is devoted to the implementation issues of IFAQ, such as the selection of quality judgement criteria, the composite score construction and the financial bonus calculation. The U.S. Value-based Purchasing initiative serves as a feasible reference here, due to similarity in program structure, and its implementation maturity. After an analysis of the reference case, some guiding principles of IFAQ approach are derived. The selection of judgement criteria for IFAQ is conducted, based on the French existing quality measurement methods, which are hospital accreditation and quality indicators. The calculation method of IFAQ score and the bonus level is then presented in detail, how categorical scores are obtained from raw data, how achievements and improvements are scored, how IFAQ final composite score is derived, and how the financial bonus level is determined.

The fifth chapter presents the statistical and econometrical assessment of IFAQ program. Firstly, methodology literature review of impact evaluation on different P4P programs is presented, which serve as references for the French case. Secondly, IFAQ evaluation method is discussed, such as test for heterogeneity as a pre-requisite, intention-to-treatment effect analysis, local average treatment effect analysis, simple difference-in-difference, difference-in-difference with propensity-score matching for the initial period, regression discontinuity for the middle-term, and panel data regression for the long term. Thirdly, empirical data are reviewed, and descriptive statistics are presented on IFAQ, for both quality indicators and a list of hospital characteristics. Fourthly, policy impact evaluation of the short term is conducted through the above methodologies.

The sixth chapter builds a research framework for possible future analysis on cost-effectiveness of P4P initiatives. This conceptual framework is based on previous studies on costs and benefits associated with P4P policy. It summarises the existing different categories of costs, such as set up/development costs, running costs, participation costs, and incentive payments. Benefit of P4P can be measured either by quality-adjusted life years, or cost savings (reduction in health

complication, in length of hospital stay, in readmission rates) resulted from P4P intervention. The cost-effectiveness of a P4P initiative is measured by the relationship between such costs and benefits, compared with existing international standards.

The seventh chapter focuses on the feasibility of transferring P4P into another context, namely China. It is a case study of P4P in the Chinese health care market. Although P4P has been a widely implemented remuneration method over the world, whether it could fit into another specific country, namely China, still remains a question. The French IFAQ case, its experiences in design, implementation and evaluation, could be served as a reference. In this way, we try to understand the reliability of some findings from IFAQ. The previous chapters have shown how international knowledge of P4P has been absorbed, digested and adapted to the French context, what kind of lessons could be learnt and what kind of pitfalls should be avoided. This experience and process could, to some extent, be standardised and be applied to other new countries willing to adopt P4P. This chapter represents such an attempt and trial. Firstly we analyse the current health care system in China and its structure of physician payment, which reveal the necessity and feasibility of introducing P4P in the health care system of China. Then the existing performance-based payment system for Chinese physicians is studied, as well as its problems in practice. Lastly, some international references are summarised, with the hope to provide useful references for fixing these problems.

The last part is a conclusion of this thesis, on the three main issues addressed by this study, namely design, implementation and evaluation of IFAQ program. It explains the French IFAQ experimentation, how the U.S. VBP program is served as a reference, and how IFAQ program differs from it. Some major differences include the choice of quality components, as IFAQ involves hospital accreditation results not only as its eligibility criteria, but also as part of its quality measurement, while VBP only uses it as the former. Secondly, IFAQ adopts categorical rather than crude numerical data, to score achievements and improvements, due to statistical uncertainty; while VBP uses numerical data. Thirdly, the simple composite score is given by the scaled sum of achievement and improvement scores, whereas the VBP program uses the higher of the two. Apart from this, we also discuss some possible reasons why P4P programs have great variety in their effects around the world. One general reason is that the particularity of medical practices distinguishes it from other fields such as corporate management, where P4P concept originates. Secondly, the specific design elements also affect the effectiveness of each P4P initiative, such as level of incentives, which directly affects the motivation for

behavior change. The conclusion part also includes perspectives for the future, as to what we can learn as these programs unfold, and how the programs can be improved. Recommendations are made as to how to build and improve a standardized design-implementation-evaluation model, and these can be explored in future researches of health care P4P, not only in developed country markets, but also in developing countries such as Chinese health sector.

1. Context for the Launch of a French Hospital P4P Initiative

This part reviews the context in which the French hospital P4P initiative, i.e. IFAQ, is launched. The necessity of such a new remuneration scheme is emphasized by both practical issues and theoretical judgements, and by both international experiences and national situations. These are synthesised in this context part, as a prelude to the development of IFAQ.

In practice, the existing medical remuneration schemes, such as salary, fee-for-service, global budget, capitation and diagnosis-related groups, don’t include reward on health service quality. Thus it is an innovation to take into account quality for remuneration. This innovative concept is also validated from different theoretical frameworks, such as agency theory from an economics perspective, medical professionalism from a sociology perspective, and quality improvement from an organisational perspective. Under the agency theory framework, P4P fixes the information-asymmetry problem between providers and payers/patients, by implementing incentives on quality for providers. From a sociology perspective, P4P contributes to the medical deprofessionalism by building a bridge between physicians’ association and the external group. It helps the latter to better understand the quality of health services they receive, and provides objective judgement and information. From an organisational perspective, P4P helps the organisation to better measure and improve health service quality; it also promotes a culture of quality among physicians and other staff within a health organisation.

Internationally, P4P has been widely introduced across a number of countries (Table 1-1). Some major initiatives have been reviewed within this context part, such as the Value-Based Purchasing program and its predecessor Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration program in the U.S. These two programs are among the most widely launched and standardised ones, which are also deeply analysed through academic researches. Five different P4P programs in the UK are discussed next, each with a specific emphasis and a different design. After that, other major programs from Germany, France, New Zealand, South Korea and Brazil are discussed. However, empirical evidences have shown that the majority of these programs lack a significantly positive effect, especially in the long run. This can be attributed to certain design elements and empirical pitfalls, which should be taken into account during the introduction of P4P in French hospitals and will be discussed in the next chapter.

Table 1-1. Pay-for-Performance Programs over the World

Country primary care Bonus for physicians If so, targets related to: Bonus for specialists If so, targets related to: Bonus for hospitals If so, targets related to:

Pr e ve n tiv e ca re Ch ro n ic di seas e Pr e ve n tiv e ca re Ch ro n ic di seas e Cl in ic a l out com e Pr o ce ss Pa tie n t sa tisf a ct io n Argentina X Australia X X X Austria Belgium X X X X X Brazil X X X Czech Republic X X X Denmark Finland France X X X Greece Hungary X Iceland Ireland Israeli X Italy X X X Japan X X X X X X X X Korea X X X Luxembourg X Mexico Netherlands New Zealands X X X Norway Pakistan X X Poland X X X X X X Portugal X X X Rwanda X X X Slovak Republic X X X X X Spain X X X X Switzerland Taiwan, China X X X X X Turkey X X X X X X United Kingdom X X X X X X X X X X United States X X X X X X X X X X

Source: Adapted from ‘Summary of OECD experience of pay for performance’, Borowitz M, Cashin C, Bisiaux R, Chi Y-L. Paying for Performance in Health in OECD Countries: lessons for development; 2011

1.1 Lack of incentives on quality in the existing remuneration methods

The existing provider payment methods include salary, fee-for-service (FFS), global budget, capitation and diagnosis-related groups (DRG). Generally speaking, salary, budget, and capitation are expected to have a strong effect on cost-containment but cause concerns on low productivity and quality. In contrast, DRG, FFS, and per diem encourage providers to deliver more and better services but give no incentives to restraining costs. Recent reforms in a group

of developed countries have demonstrated a movement towards the simultaneous use of different provider payment methods. For example, in Finland, physicians’ remuneration consists of a basic salary (60%), a capitation amount (20%), FFS (15%) and a local allowance (5%) [5]. Below is a discussion of different payment methods, their advantages and disadvantages [6]. Nevertheless, no matter which method, or mixed methods, there lack an emphasis on health care quality, which necessitates the introduction of P4P.

Salary

It is a payment to the physician or other health care provider regardless of number of patients seen or the volume or cost of services provided. Under this payment system physicians bear little financial risk and may alter their decision-making to minimize the time and effort spent at work. Therefore, salaried doctors in the public sector are often associated with low motivation, low productivity and low quality of services. Salaries tend to be determined by seniority and length of services; they are generally negotiated centrally between physicians’ associations and the government. The advantage of salaries is its equity and stableness, which restrains for-profit risk-taking (eg. gaming behaviour). It also makes administrative process simple and easy. Empirical evidence suggests that in addition to low productivity and quality, another disadvantage of salaries could be the informal payment of out-of-pocket money by patients. In Hungary, most medical specialists are public employees and salaried. They receive the bulk of informal payments. Since 2002, the government has raised the salary by an average of 50% to tackle this problem [5]. However, though augmentation of salary levels can deter informal payments, such higher remuneration is not conditional, and bears no incentive on quality. In other words, the ‘low motivation, low productivity’ problem is still not solved.

Fee-for-Service (FFS)

This method pays providers according to number of services delivered. The advantages of FFS are the associated high accessibility of health care services and high quality of treatment in the presence of competition. It is still one of the most widely used methods for private sector providers, in both developed and developing counties, especially in priority services such as vaccinations and ambulatory care. This payment method tends to promote excessive use of services and can increase costs. One major problem in practice is induced demand, which leads to oversupply of services above the level that would be clinically justified [7]. Financial risks

under FFS are borne by the purchaser. Thus there is no incentive for physicians to focus on technological progress that could lead to less costly treatments. On the contrary, they can gain from more costly treatments and equipment.

In the 1990s, with the adoption of social health insurance systems, a group of countries such as Czech Republic, Croatia, Slovakia, and Ukraine, moved from input-based payment to reimbursement by FFS. This quickly increased activity levels, and put financial pressures on the purchasers, causing them to negotiate volume contracts within a capped budget, or prospective global budgets with activity caps [8]. FFS has also been an important payment method in Belgium, Germany, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Switzerland and the U.S. In those countries patients enjoy the freedom to directly choose their physician and generally benefit from an adequate access to health care services. Doctors working under this FFS framework also undertake efforts to improve the quality of health care services in order to attract more patients [5]. However, in 1990s, Belgium also reformed its health care system in order to eliminate abuse, inefficiency, over supply and over consumption, resulted from the nature of FFS system. A rather extreme example, however, concerns Chinese health providers: the volume of services increases exponentially when FFS becomes almost the exclusive payment methods. As hospitals are paid by the number of admissions, there has been an explosion in hospital admissions. Unfortunately, since health insurance, though rapidly increasing, is very limited in China, these increases in services are largely paid for by out-of-pocket money from patients [7, 9].

All in all, the above evidences confirm that FFS is generally associated with over-consumption of health care services. Although FFS stimulates doctors to improve quality in order to attract more patients, this mechanism works only under a competitive environment and cannot avoid the problem of induced demand. In other words, FFS itself doesn’t provide a method both to control health care costs and to increase quality.

Capitation

Under this scheme providers are paid a fixed amount of money on the basis of number of patients for delivering a range of services, during a fixed period of time –usually a month or a year. Capitation is more often applied to outpatient providers such as general practitioners (GPs), and less often to specialists. The advantages of capitation are effective cost containment

and incentives for preventive care provision. Its disadvantages include risk selection and under-provision of services. As capitation shifts the financial risks to providers, who are responsible for any costs above the capitation rate and are able to keep any unused funds, GPs under this payment scheme tend to enrol only healthy patients and refer sick patients on to specialists. They also tend to under-provide services and tests, or to limit drugs prescription, if they fall under the capitation. One remedy is case-mix adjustment. Adjusted capitation payment according to patients’ profile such as age and sex can help guarantee quality of service and equitable access to care, by stimulating GPs to accept and treat patients with various characteristics [5, 6].

In Czech, Denmark, Finland, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Slovakia, UK, a combination payment of capitation and FFS has been implemented. In Estonia, the capitation payment system is mixed with an age-adjusted per capita rate, an FFS factor for some specified services, and a fixed allowance for infrastructure and equipment. This hybrid payment results in diluted efficiency incentives and stronger incentives to increase services paid separately through FFS [8].

In a word, while, unlike FFS, capitation easily controls health care costs, it bears totally no incentive on quality promotion. In addition, it gives rise to two undesirable effects of health service under-provision and patient-selection. It is thus not an ideal payment method, neither is its combination with FFS, which still provides no incentive on health care quality.

Budget

This payment scheme sets incentives for hospitals to employ more of the input factors based on which the budget is defined and operate within the allocated budget. There are global budgets and sectoral/line-item budgets. Rigid budget formulation and inflexibility of the latter limits the reallocation of funds across line-items or sectors to better respond to changes in utilization or patient needs. Global budgets at the hospital level, on the other hand, is a payment fixed in advance to cover the aggregate expenditures of that hospital over a given period to provide a set of services that have been broadly agreed upon. A global budget may be based on either inputs or outputs, or a combination of the two [8]. Under such a scheme, incentives are created for managers to control hospital expenses, to set volume limits, and often to exert caps on subsectors, including ambulatory care and pharmaceuticals. So the advantages of budget are

efficiency in cost containment and simplicity in administration, while its disadvantages include low investment in technologies or other infrastructures due to a rigid budget. In addition, selection of patients is also possible, under the same logic as FFS. With sectoral budget, patient shifting and other cost substitution across different service sectors is a problem difficult to tackle with in practice [5, 6].

Since 1970s budgets have been introduced as health care cost-containment instruments in a substantial number of OECD countries. In several countries such as Czech, Hungary, the Netherlands and Poland, budgets are used in combination with FFS, to limit the health care overprovision tendency. In the mid-1980s prior to hospital payment reform in Western Europe, most public hospitals were paid a fixed line-item budget based on inputs such as the number of staff and hospital beds. Since 2000, in the Netherlands, hospital financing efforts have been undertaken to integrate the FFS system for specialists and the hospital budget system into a single integrated budget [10].

In a nutshell, while the budget scheme is efficient in cost-containment, it creates quite a few problems such as inflexibility of resource allocation in response to patients’ needs, low investment in infrastructure, and patient selection or shifting. Still, health service performance is not accounted for by this remuneration method, potentially leaving physicians and managers more concerned by the health care expenses instead of quality.

DRG

The Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRG) system is a patient classification system developed to classify patients into groups economically and medically similar, expected to have comparable hospital resource use and costs. Under DRG scheme, providers are reimbursed at a fixed rate per discharge based on diagnosis, treatment and type of discharge. Advantages of this payment method are effective cost containment, most cost-effective treatment adopted, and reduction in unnecessary care, which is rather prevalent under FFS scheme. However, DRG also sets incentives for providers to select patients by focusing on more profitable ones with less severe conditions under the same case-mix, to increase number of admissions, to shorten patients’ average length of stay by premature discharge, and to monitor costs by providing less care. [5, 6, 8]

DRG was first introduced in the U.S. Medicare system in 1983. Based on this U.S. DRG categorisation, a group of countries developed their own DRG, such as Australia, Germany, and Switzerland. Alternative classification systems such as the ‘Nosology-based’ system were adopted in several Former Soviet Republics, while some middle-income countries such as China and Estonia experimented with simpler classification than the DRG, due to a lack of data or to reduce administrative costs [5].

In a group of countries such as Australia, Czech, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Italy, New Zealand, and Norway, DRG system has been combined with budget payment scheme to remunerate specific hospital departments, while respecting a pre-determined budget for the hospital as a whole. The case-mix adjusted budget improves service accessibility to patients with severe conditions. In Portugal, with the implementation of such a model, the DRG case-mix adjusted component of each hospital’s budget rose from 10% in 1997 to 50% in fiscal year 2002. In Australia, DRG payment is considered to be efficient but criticized for ‘quicker but sicker discharge’ [5]. In a word, the disadvantages associated with capitation or budgeting, such as under-provision of services and patient-selection, still exist with DRG system. Attention is now being paid to developing comparable measures of quality and health outcomes.

The introduction of these above cost containment instruments could date back to the 1970s during the global economic recession. Decades before that, social security system and universal health care coverage have been widely introduced across industrialised countries. The landmark passage of Medicare and Medicaid legislation in 1965 increased access to health care for millions of elderly, low-income, and other Americans who did not have health insurance through employer-based or commercial plans. In France, universal health care was implemented step by step during the second half of the twenties century [11]. Meanwhile, given the rapidly aging population and more advanced technology in health care devices, the increase of health expenditures has also accelerated. However, such an increase is systemically inconsistent with the increase in GDP for OECD countries, as the total expenditure on health care accounted for 8.8% of GDP in 2003 and 8.9% in 2013, compared to 7.8% in 1997 [5, 12]. Following the 1970s’ global economic recession, there is pressing need of health care expenditure cutting. The above capitation and DRG payment system were developed under this situation, to control health care costs.

However, evidences showed that there existed large and unexplained variations in rates of health care utilization and clinical outcomes [13], which put into question the effectiveness of existing remuneration methods and the traditional reliance on the medical profession to ensure the quality of health care services. This raises the consensus that, in the long term health care cost control requires not only cuts in service volume, but more importantly, increase in service quality. Furthermore, such quality promotion should be directed by a third-party other than the medical profession itself. If high costs are to some extent inevitable in the high-technology environment of health care, then the health outcomes should be better, or the cost-efficiency should be higher. The current facts that high-cost is not necessarily associated with high quality of care [14, 15], can be due to the fact that none of the above existing payment methods concern the quality of health service delivered. Thus it is necessary to introduce another incentive based on quality, to balance the above quantity-based payment schemes, and to achieve the double targets of cost containment and quality improvement.

1.2 The Introduction of P4P in Different Countries

P4P is, from time to time, referred to by different terms, such as paying for results, results-based financing (RBF), pay-for-quality, etc. Table 1-2 presents a list of different definitions by different health organizations in the world, which are involved with P4P analysis and implementation.

The first three definitions take a perspective of the U.S., where P4P originated. They are defined by: 1) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), 2) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and 3) Research and Development Corporation (RAND). The CMS one emphasizes patient-focused services, whereas the RAND definition includes efficiency measure as an extra compared to others. The latter three definitions are more concerned with developing countries, and in fact include both incentives to providers and to patients for achieving certain performance targets. They are developed by: 4) the World Bank, 5) USAID, and 6) Center for Global Development. The last one rewards actions, as well as performance results, of health care services.

Whereas these definitions are rather general, there are plenty of concrete examples of P4P initiatives over the world. A close analysis of these practical examples is a pre-requisite for developing the French P4P program. In this part, some major P4P initiatives implemented in different countries, namely the United States, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Germany, France, South Korea and Brazil, are presented and discussed. Some initiatives are targeted at general practitioners, while others at hospitals or physician groups. A group of other design factors are retrieved and listed in the following section for analysis, based on a review of these different programs over the world.

Table 1-2. Pay-for-Performance Definitions

Organization P4P definition

AHRQ Paying more for good performance on quality metrics.

CMS The use of payment methods and other incentives to encourage quality improvement and patient-focused high value care.

RAND

The general strategy of promoting quality improvement by rewarding providers (physicians, clinics or hospitals) who meet certain

performance expectations with respect to health care quality or efficiency.

World Bank A range of mechanisms designed to enhance the performance of the health system through incentive-based payments.

USAID P4P introduces incentives (generally financial) to reward attainment of positive health results.

Center for Global Development

Transfer of money or material goods conditional on taking a measurable action or achieving a pre-determined performance target.

Source: Value for Money in Health Spending, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD

1.2.1 The United States

The Premier Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration (HQID) initiative, the predecessor to the current Value-Based Purchasing program, is a nation-wide pay-for-performance program for healthcare providers in the United States, launched by Medicare and Premier Inc. as a demonstration program in 2003.

Hospitals that participate in HQID program were required to collect and submit data on 34 indicators covering both process and patient outcomes. These indicators measure performance in 5 acute clinical conditions: health failure, community acquired pneumonia, hip and knee replacement, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), coronary artery bypass graft. The results are combined into a composite indicator for each of the clinical condition. Hospitals were required to participate in all five of the clinical areas, but if there were fewer than 30 cases in a clinical area the hospital was excluded from that area.

During the first two years of this program (FY2004, FY2005), hospitals were ranked on their performance in all areas of care. For each of the clinical conditions, hospitals performing in the top decile on a composite measure of quality for a given year received a 2% bonus payment in addition to the usual Medicare reimbursement rate. Hospitals in the second decile received a 1% bonus. From the third year (FY 2006) on, financial penalties were added to the program, whereas bonuses continued. Hospitals failing to exceed the lowest decile performance had to pay a penalty of 2% of Medicare payments; and 1% for those in the next-to-lowest decile hospitals. Beginning with year 4 results, an additional attainment award and an improvement award were implemented, which is meant to provide incentives for both high- and low-baseline performers.

On March 31, 2003, enrollment in the project opened to 414 Premier hospitals, of which 267 (64%) initially agreed to participate. During the first five years, Medicare has awarded $48 million in total. Quality scores increased by an average of 18.3 percent over five years, though long term effect of the program was questionable [16, 17].

Value-Based Purchasing (VBP)

The Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program is a P4P initiative established by the Affordable Care Act of 2010, which applies to payments beginning in Fiscal Year (FY) 2013, i.e. from 1st October 2012, and affects inpatient stays in 2985 hospitals across the country [18].

It rewards acute-care hospitals with financial incentives for the quality of care they provide to patients with Medicare and Medicaid.

Hospital performance is evaluated by an approved list of dimensions and quality indicators (measures), grouped into specific domains. In FY2013, two domains are applied: clinical process of care and patient experience of care. In FY2014, an outcome domain is added; while in FY2015, an additional efficiency domain is added. The list of indicators for FY2014 can be found in Table 1-3. For each quality indicator (or ‘measure’), an achievement score (ranging from 0 to 10) and an improvement score (ranging from 0 to 9) is calculated, and the measure score is obtained by taking the higher one of achievement and improvement score. Domain score is the average of measure scores within that domain [19]. For patient experience domain, there is an additional consistency score, which is based on the lowest score across the eight different measures under patient experience domain. A hospital is awarded the maximum 20 points when its performance on each dimension equals or exceeds the 50th percentile across all

participants. This consistency score is added into the patient experience domain score [20]. The total performance score is calculated as weighted average of domain scores. These weights adjust over the years as shown in Table 1-4.

The reward payments are financed by retaining a certain percentage of Medicare reimbursement from participating hospitals. This retained percentage changes over the years (ranging from 1% to 2%). CMS finalized a linear exchange function to translate total performance score into value-based incentive payments. In other words, each participating hospital receives the VBP payment, the amount of which depends on its total performance score compared to all the other hospitals.

Others P4P programs in the U.S.

Apart from VBP or HQID, there are also other P4P programs in the U.S., such as Care Management for High-Cost Beneficiaries Demonstration, Integrated Healthcare Association, Bridges to Excellence, etc. They are launched by different private and public organizations in addition to Centres for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and are targeted at different providers, in different regions.

Even within the scheme of Medicare, from fiscal year 2015 to 2017, three separate P4P programs are expected to coexist, namely Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, the VBP program, and the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program, affecting the amount of Medicare payment for inpatient services to about 3400 US hospitals. There are overlap in quality measures and differences in scoring hospital performance. However, VBP is the only one of the three programs to explicitly recognise improvement in hospital performance as well as achievement of specific targets in determining a hospital’s total performance score and payment adjustment. A larger proportion of Medicare hospital payments, 6 percent by 2017, are dependent upon how hospitals perform under the combination of all three programs. One concern is that such cross-contraction produces complex incentive focuses, which may not be perfectly aligned to each other. Then the impact of each P4P program may be blunted [11, 21]. In the future, new payment models are conceived for specialty care, starting with oncology treatment, and care coordination for patients with chronic conditions. In addition, greater integration within practice sites and greater attention to population health are to be encouraged. Furthermore, through the adoption of health information technology, i.e. electronic health records (EHRs) and their meaningful use, ongoing efforts will advance informed clinical decisions for physicians and information transparency for consumers [22].

Table 1-3. Quality Domains and Measures in the Value-based Purchasing Program, FY2014

Sources: National Provider Call: Hospital Value-Based Purchasing. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2012 [updated 2012; cited]; Available from:

http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality- Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/index.html?redirect=/hospital-value-based-purchasing.

Table 1-4. Weighted Value of Each Domain

Domain FY 2013 Weight FY 2014 Weight FY2015 Weight

Clinical process

of care 70% 45% 20%

Patient experience

of care 30% 30% 30%

Outcome N.A. 25% 30%

Efficiency N.A. N.A. 20%

Information sources: Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2013.

1.2.2 The United Kingdom Best Practice Tariff (BPTs)

In April 2010, Best Practice Tariffs was launched by the Department of Health in England, as a hospital P4P program, aiming to reduce unexplained variation in clinical quality and ensure that best practice is widespread. The scheme was initially designed to provide financial incentives on four high-volume clinical areas: cataract surgery, gall bladder removal, stroke, and fragility hip fracture. A group of other areas such as paediatric diabetes, transient ischemic attack, major trauma and outpatient procedures were added over the years. A specific approach is developed for each BPT area, tailored to the clinical characteristics of best practice and the availability and quality of data [23].

Whatever the specific approach, three principals are followed: to change the setting of care, often from inpatient to day case1 (eg. gall bladder removal); to streamline care pathways (eg.

reducing the amount of outpatient appointments for each patient for which hospitals are reimbursed); to incentivise the provision of high quality and cost-effective care based on the best available evidences [24].

First year results show that, under the incentive of promoting day case and reducing inpatient care, day-case rate increased by 7 percentages, with no evidence of gaming in the sense of reducing quality or selecting patients more amenable to day-case treatment. However, the waiting time for treatment increased by 14 days on average, which was likely due to the increased demand on day-case facilities. During the first year, there appeared no impact on stroke measures, while substantial effects on the hip fracture measures. This may be attributable to the different structures of the tariffs, as the BPT for hip fracture is only paid if all criteria are met whereas providers are rewarded separately for each indicator in the stroke BPT [23]. Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) framework

1

A surgical day case is defined by the Royal College of Surgeons of England as “a patient who is admitted for investigation or operation on a planned non-resident basis and who nonetheless requires facilities for recovery”. Day case surgery must be distinguished from ‘out-patient cases’. These are minor procedures performed under a local anaesthetic which do not generally require postoperative recovery time.

The Commissioning for Quality and Innovation framework was introduced across England in April 2009 [25, 26]. It covers medical services concerning acute, ambulance, community, mental health and learning disability treatments. Four quality dimensions are incentivised: safety, effectiveness, patient experience, and innovation. Under a guideline outlining these four dimensions, local commissioners and providers decide on the CQUIN indicators themselves. They are also encouraged to select outcome measures over process and structure indicators, and to use existing national indicators where available. This local aspect distinguishes CQUIN framework from other P4P programs, and is intended to generate more enthusiasm from providers, and to facilitate program implementation. However, results show that generally there is no impact from CQUIN on quality improvement [27]. Whilst the programme had managed to identify local priorities, the desired enthusiasm did not manifest, and the resulting local CQUIN indicators did not meet the design requirements of the Department of Health [28].

Never Events policy

The English Never Events policy, which took effect from March 2009, follows the trend concerning non-payment for performance [29], which is to withhold payment when certain undesired behaviours occur. There is non-payment for never events (eg. wrong site surgery, severe scalding of patients, and unintended retention of a foreign object in a patient after surgical intervention), and for certain readmissions occurring within 30 days of discharge from an elective admission. The implementation of these programs have, however, been met with resistance from the medical community [30-32]. In addition, there is no clear evidence on the impact of this policy.

Advancing Quality (AQ) scheme

Advancing Quality was the first hospital-based pay-for-performance scheme in the UK, covering all 24 NHS hospitals in the North West region of England. It is modelled on the U.S. HQID program, including three rewards: attainment award, for hospitals exceeding the median score across all hospitals in the first year; improvement award, for those whose improvement score in the top quartile; and an achievement award, for those score in the top two quartiles of absolute performance (4% of the national tariff revenue for the top quartile, and 2% for the second quartile). AQ program includes 28 quality indicators, covering patients admitted in an emergency for three health conditions (acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure,

pneumonia) and for two types of planned surgery (coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and hip and knee replacements). Evidence shows that this P4P program is effective, and reduces significantly the risk-adjusted mortality rate [33]. What is worth mentioning for AQ scheme is its ‘shared learning’ activities, where top performers would share their tips for success, thus a collaborative atmosphere is promoted in addition to competition [23].

Quality and Outcome Framework (QOF)

Quality and Outcomes Framework, starting in 2004, is a P4P program in UK for general practitioners. It measures 134 indicators in four domains (the 2010-2011 QOF): clinical care, organization, patient experience and additional services. The composition of indicators evolve over the years. Although it is a program with voluntary participation of general practitioners, nearly all of them have participated; leading to the fact that this program covers almost 100% of registered patients in UK (NHS, 2009; NHS, 2011). The average additional income from the QOF was on average £74,300 per GP practice in 2004-05 and £126,000 in 2005-06, which makes up on average 20% of the annual GP practice income. This proportion of reward tied to quality of care is large compared to its international counterparts [34].

English family practices attained high levels of achievement in the first year of the new pay for performance contract, though a small number of practices appear to have achieved high scores by excluding large numbers of patients by ‘exception reporting’. This is a rule in QOF that gives physicians the right, based on a range of criteria, to exclude individual patients from the quality calculations that determine their pay. This process is intended to safeguard patients against inappropriate treatment by physicians seeking to maximize their income. More research is needed to determine whether these practices are excluding patients for sound clinical reasons or in order to increase income [35].

Campbell S., et al. (2007) found that the introduction of QOF in 2004 was associated with a modest acceleration in improvement for diabetes and asthma, despite some statistical limitations in their evaluation, which will be discussed later. Concerns are that more money has been paid than necessary to achieve high performance against the targets.

Pay-for-performance program was introduced in the health care sector of New Zealand in 2006, titled the Performance-Based Management (PBM) program. The aim of this program was both to improve population health outcomes and to reduce health disparities, through financial incentives in Primary Health Organisations (PHOs). PHOs are not-for-profit, non-governmental groups of individual general practitioners (GP) practices that serve patients who enroll within a geographic area. PBM is one piece of an overall quality framework, designed by primary health care representatives, New Zealand District Health Boards and the Ministry of Health, to achieve the above two goals.

The performance domains and indicators covered by PBM are: 1) coverage domain: breast cancer screening coverage, cervical cancer screening coverage, 65+ years influenza vaccine coverage, age appropriate vaccinations for 2-year-olds; 2) clinical quality domain: ischaemic cardiovascular disease detection, cardiovascular disease risk assessment, diabetes detection, diabetes follow-up after detection; 3) efficiency domain: GP referred laboratory expenditure, GP referred pharmaceutical expenditure. As the program has an aim to reduce health care inequality, some indicators are measured separately for ‘high-need populations’, which are rewarded at a higher rate. The PHO’s high needs population is defined by the sum of individual enrolled patients who are Maori (the indigenous population of New Zealand), Pacific Islanders or living in geographic areas with high relative socioeconomic deprivation. P4P payments, as well as health care expenditure targets, are also weighted towards progress in these indicators on high needs population. [36]

Each performance measurement period lasts six months, with performance targets re-negotiated based on level completion of previous phase, or their baseline performance for the first phase. Participation to PBM is voluntary. It covers nearly 100 percent of GPs and primary care nurses, though the network of PHOs, and about 98 percent of the population. The setup payment is NZD 20 000 per PHO plus 60c per enrolled member. The guaranteed minimum payment is NZD 1.00-1.50 per enrollee and the maximum payment is NZD 6 per enrollee if all targets are obtained. This initial level is finely adjusted over later years [2]. The total amount of performance payment is small, which makes up less than one percent of the government primary care budget.

Indicator results are made to the public, with only modest improvements detected for performance indicators. Evidences concerning the overall impact on equity and reducing health

disparities are mixed. However, no clear and reliable conclusion can be drawn, given the absence of a rigorous evaluation of the program, or at least more systematic monitoring and analytical assessments. An important positive impact concerns the spill-over effect on data-collection infrastructure development. Automatic data reporting has been introduced, to replace the previous manual work. However, the implementation of PBM was perceived as being imposed from the top and bureaucratic. There was a disconnect between program management, payment of the incentive, and clinical providers, and the role of PHOs had never been fully clarified. [36]

1.2.4 Germany

Care of chronic conditions has long been detected as one major source of deficiencies in German health care system. In spite of the clear clinical guidelines and protocols in this area, defined by the Ministry of Health, there were in reality no effective incentives for physicians to implement and follow these guidelines, which results in inefficient care for chronic conditions (especially multiple chronic ones) and also large variations in health care quality.

In 2002, Disease Management Program (DMP) was introduced in Germany as part of a 2002 reform by the German Statutory Health Insurance System (SHI), which covers 88% of the population (2004). It is aimed to improve quality and continuity of care for chronically ill patients, by creating a network of physicians for treatment coordination. Five large areas of chronic illness and breast caner are covered by the program: diabetes (type 1 and 2), breast cancer, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and coronary heart disease.

This DMP program is financially implemented through sickness funds, the law-enforced health insurance in Germany. For each patient enrolled, sick funds receive 180 euros to cover administrative and management costs of coordinated care in 2010 (168 euros in 2007). Additional payments are made to physicians for provision of coordinated care, as agreed in the contract. To take an example of Thüringen, an additional payment of up to 35 euro (10 euros for documentation and 25 euros for administrative costs) per patient enrolled in coronary heart disease is made to individual general practitioners. In some complex co-morbidities, which require additional management, sickness funds can also provide incentives to cardiologists for coordination. Incentives to patients are also provided by sickness funds, in order to enroll as