HAL Id: dumas-01689952

https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01689952

Submitted on 22 Jan 2018

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License

What is the internal validation and dimensionality in

the translation of HSCL-25 in French, in the diagnosis of

depression in primary care?

Anne-Laure Pellen

To cite this version:

Anne-Laure Pellen. What is the internal validation and dimensionality in the translation of HSCL-25 in French, in the diagnosis of depression in primary care?. Life Sciences [q-bio]. 2017. �dumas-01689952�

UNIVERSITÉ DE BREST - BRETAGNE OCCIDENTALE

Faculté de Médecine et des Sciences de la Santé

*****

Année 2017

THÈSE DE

DOCTORAT en MÉDECINE

-

DIPLOME D’ÉTAT

-

SPÉCIALITÉ : Médecine Générale

Quelle est la validation interne et la dimensionnalité de la

version française de la « Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25 »,

dans le diagnostic de la dépression en soins primaires ?

What is the internal validation and dimensionality in the

translation of HSCL-25 in French, in the diagnosis of

depression in primary care?

Par Mlle PELLEN Anne-Laure

Née le 09 Mai 1990 à Brest (Finistère)

Présentée et soutenue publiquement le 15/06/2017

PRÉSIDENT DU JURY Pr. Jean Yves LE RESTE MEMBRES DU JURY Dr. Patrice NABBE

Pr. Bernard LE FLOC’H Florence GATINEAU

UNIVERSITE DE BRETAGNE OCCIDENTALE

FACULTE DE MÉDECINE ET

DES SCIENCES DE LA SANTÉ DE BREST

PROFESSEURS EMÉRITES

Professeur BARRA Jean-Aubert Chirurgie Thoracique & Cardiovasculaire Professeur LAZARTIGUES Alain Pédopsychiatrie

PROFESSEURSDES UNIVERSITÉSEN SURNOMBRE

Professeur BLANC Jean-Jacques Cardiologie Professeur CENAC Arnaud Médecine Interne

PROFESSEURSDES UNIVERSITÉS - PRATICIENS HOSPITALIERSDE CLASSE EXCEPTIONNELLE

BOLES Jean-Michel Réanimation Médicale FEREC Claude Génétique

GARRE Michel Maladies Infectieuses - Maladies tropicales MOTTIER Dominique Thérapeutique

PROFESSEURSDES UNIVERSITÉS - PRATICIENS HOSPITALIERSDE 1ère CLASSE

ABGRALL Jean-François Hématologie - Transfusion

DOYENS HONORAIRES: Professeur H. H. FLOCH Professeur G. LE MENN ( )

Professeur B. SENECAIL

Professeur J. M. BOLES Professeur Y. BIZAIS ( )

Professeur M. DE BRAEKELEER DOYEN : Professeur C. BERTHOU

BOSCHAT Jacques Cardiologie & Maladies Vasculaires BRESSOLLETTE Luc Médecine Vasculaire

COCHENER - LAMARD Béatrice Ophtalmologie

COLLET Michel Gynécologie - Obstétrique DE PARSCAU DU PLESSIX Loïc Pédiatrie

DE BRAEKELEER Marc Génétique

DEWITTE Jean-Dominique Médecine & Santé au Travail FENOLL Bertrand Chirurgie Infantile

GOUNY Pierre Chirurgie Vasculaire JOUQUAN Jean Médecine Interne

KERLAN Véronique Endocrinologie, Diabète & maladies métaboliques LEFEVRE Christian Anatomie

LEJEUNE Benoist Epidémiologie, Economie de la santé & de la prévention LEHN Pierre Biologie Cellulaire

LEROYER Christophe Pneumologie LE MEUR Yannick Néphrologie

LE NEN Dominique Chirurgie Orthopédique et Traumatologique LOZAC’H Patrick Chirurgie Digestive

MANSOURATI Jacques Cardiologie

OZIER Yves Anesthésiologie et Réanimation Chirurgicale REMY-NERIS Olivier Médecine Physique et Réadaptation

ROBASZKIEWICZ Michel Gastroentérologie - Hépatologie SENECAIL Bernard Anatomie

SIZUN Jacques Pédiatrie

TILLY - GENTRIC Armelle Gériatrie & biologie du vieillissement

PROFESSEURSDES UNIVERSITÉS - PRATICIENS HOSPITALIERSDE 2ème CLASSE

BAIL Jean-Pierre Chirurgie Digestive

BERTHOU Christian Hématologie – Transfusion

BLONDEL Marc Biologie cellulaire BOTBOL Michel Psychiatrie Infantile

CARRE Jean-Luc Biochimie et Biologie moléculaire COUTURAUD Francis Pneumologie

DAM HIEU Phung Neurochirurgie DEHNI Nida Chirurgie Générale DELARUE Jacques Nutrition

DEVAUCHELLE-PENSEC Valérie Rhumatologie

DUBRANA Frédéric Chirurgie Orthopédique et Traumatologique FOURNIER Georges Urologie

GILARD Martine Cardiologie GIROUX-METGES Marie-Agnès Physiologie

HU Wei go Chirurgie plastique, reconstructrice et esthétique, rudologie

LACUT Karine Thérapeutique LE GAL Grégoire Médecine interne LE MARECHAL Cédric Génétique

L’HER Erwan Réanimation Médicale MARIANOWSKI Rémi Otto. Rhino. Laryngologie MISERY Laurent Dermatologie - Vénérologie NEVEZ Gilles Parasitologie et Mycologie NONENT Michel Radiologie & Imagerie médicale NOUSBAUM Jean-Baptiste Gastroentérologie - Hépatologie PAYAN Christopher Bactériologie – Virologie ; Hygiène PRADIER Olivier Cancérologie - Radiothérapie RENAUDINEAU Yves Immunologie

RICHE Christian Pharmacologie fondamentale SALAUN Pierre-Yves Biophysique et Médecine Nucléaire SARAUX Alain Rhumatologie

STINDEL Éric Bio-statistiques, Informatique Médicale et technologies de communication

VALERI Antoine Urologie

WALTER Michel Psychiatrie d'Adultes

PROFESSEURS des Universités – Praticien Libéral

LE RESTE Jean Yves Médecine Générale

PROFESSEURS ASSOCIÉS

LE FLOC’H Bernard Médecine Générale

MAITRES DE CONFERENCESDES UNIVERSITÉS - PRATICIENS HOSPITALIERS HORSCLASSE

ABALAIN-COLLOC Marie Louise Bactériologie – Virologie ; Hygiène AMET Yolande Biochimie et Biologie moléculaire LE MEVEL Jean Claude Physiologie

LUCAS Danièle Biochimie et Biologie moléculaire RATANASAVANH Darmon Pharmacologie fondamentale SEBERT Philippe Physiologie

MAITRES DE CONFERENCESDES UNIVERSITÉS - PRATICIENS HOSPITALIERSDE 1ère CLASSE

ABALAIN Jean-Hervé Biochimie et Biologie moléculaire AMICE Jean Cytologie et Histologie

CHEZE-LE REST Catherine Biophysique et Médecine nucléaire DOUET-GUILBERT Nathalie Génétique

JAMIN Christophe Immunologie MIALON Philippe Physiologie

MOREL Frédéric Médecine & biologie du développement et de la reproduction

PERSON Hervé Anatomie

PLEE-GAUTIER Emmanuelle Biochimie et Biologie Moléculaire UGO Valérie Hématologie, transfusion

VALLET Sophie Bactériologie – Virologie ; Hygiène VOLANT Alain Anatomie et Cytologie Pathologiques

MAITRES DE CONFERENCESDES UNIVERSITÉS - PRATICIENS HOSPITALIERSDE 2ère CLASSE

DELLUC Aurélien Médecine interne DE VRIES Philipe Chirurgie infantile HILLION Sophie Immunologie

LE BERRE Rozenn Maladies infectieuses-Maladies tropicales LE GAC Gérald Génétique

LODDE Brice Médecine et santé au travail

QUERELLOU Solène Biophysique et Médecine nucléaire SEIZEUR Romuald Anatomie-Neurochirurgie

MAITRESDECONFERENCES-CHAIREINSERM

MIGNEN Olivier Physiologie

MAITRES DE CONFERENCES

AMOUROUX Rémy Psychologie

HAXAIRE Claudie Sociologie - Démographie LANCIEN Frédéric Physiologie

LE CORRE Rozenn Biologie cellulaire

MONTIER Tristan Biochimie et biologie moléculaire MORIN Vincent Electronique et Informatique

MAITRESDECONFERENCESASSOCIESMI-TEMPS

BARRAINE Pierre Médecine Générale NABBE Patrice Médecine Générale CHIRON Benoît Médecine Générale

AGREGES DU SECOND DEGRE

MONOT Alain Français RIOU Morgan Anglais

Remerciements

Je remercie le jury :Au Professeur Jean-Yves Le Reste, je vous remercie de me faire l’honneur de présider ce jury de thèse.

Au Professeur Bernard Le Floc ‘h, je vous remercie de participer à ce jury de thèse.

Au Docteur Patrice Nable, je vous remercie d’avoir dirigé cette thèse, de m’avoir proposé de participer à ce travail de recherche. Soyez assuré de ma reconnaissance et de tout mon respect.

La statisticienne, Gatineau Florence, pour son aide et son travail.

Je tiens à remercier :

Mon groupe d’apprentissage à la recherche, pour votre aide dans l’élaboration, la rédaction et la recherche bibliographique ainsi que pour vos avis et conseils.

Je remercie les médecins qui m’ont permis de me construire et de faire des choix :

Au Docteur Stéphane Abguillerm, médecin à SOS Brest, pour m’avoir fait découvrir pendant mon externat la médecine générale.

Au Docteur Lydie Abaléa, au Docteur Nadège Delaperrière, au Docteur Severine Croly, médecins aux services des Urgences Pédiatriques pour m’avoir permis de prendre confiance en moi.

Je remercie avec plaisir le Docteur Viala Jeanlin de m’avoir accueillie dans son cabinet de médecine générale à Plogoff. J’ai énormément appris sur le plan personnel et professionnel. Je le remercie de m’avoir fait découvrir et aimer la médecine rurale.

Je remercie ma tutrice :

Le Docteur Catherine Bourillet, de m’avoir accompagné dans mon 3e cycle avec sérieux et sympathie.

Je remercie mes proches :

Tout d’abord, à ma mère, pour ton affection, le soutien que tu m’as apporté. A mon frère, Mathieu, pour son soutien et pour sa relecture avisée.

A mes grands-parents, Louis et Annik, pour votre générosité, d’avoir toujours cru en moi et m’avoir soutenu pendant toutes ses années.

A ma famille, mes cousins, mes cousines, mes oncles et tantes. Au « bon docteur Marcel » pour m’avoir encouragé à choisir la médecine générale après l’ECN. Pour le plaisir de passer des moments en famille.

A mes amies, à Elodie, Emma et en particulier à Marion et Marine pour m’avoir supportée durant toutes ses années, soutenu et écoutée. Merci pour votre joie de vivre.

A mes co-internes

Et je remercie :

Les médecins, infirmiers, aides-soignants et personnels paramédicaux rencontrés pendant mes études.

A tous ceux qui ont fait de moi, le médecin que je suis aujourd’hui. Merci

Serment d'Hippocrate

Au moment d’être admis à exercer la médecine, je promets et je jure d’être fidèle aux lois de l’honneur et de la probité.

Mon premier souci sera de rétablir, de préserver ou de promouvoir la santé dans tous ses éléments, physiques et mentaux, individuels et sociaux.

Je respecterai toutes les personnes, leur autonomie et leur volonté, sans aucune discrimination selon leur état ou leurs convictions. J’interviendrai pour les protéger si elles sont affaiblies, vulnérables ou menacées dans leur intégrité ou leur dignité. Même sous la contrainte, je ne ferai pas usage de mes connaissances contre les lois de l’humanité.

J’informerai les patients des décisions envisagées, de leurs raisons et de leurs conséquences.

Je ne tromperai jamais leur confiance et n’exploiterai pas le pouvoir hérité des circonstances pour forcer les consciences.

Je donnerai mes soins à l’indigent et à quiconque me les demandera. Je ne me laisserai pas influencer par la soif du gain ou la recherche de la gloire.

Admis dans l’intimité des personnes, je tairai les secrets qui me seront confiés.

Reçu à l’intérieur des maisons, je respecterai les secrets des foyers et ma conduite ne servira pas à corrompre les mœurs.

Je ferai tout pour soulager les souffrances. Je ne prolongerai pas abusivement les agonies. Je ne provoquerai jamais la mort délibérément.

Je préserverai l’indépendance nécessaire à l’accomplissement de ma mission. Je n’entreprendrai rien qui dépasse mes compétences. Je les entretiendrai et les perfectionnerai pour assurer au mieux les services qui me seront demandés.

J’apporterai mon aide à mes confrères ainsi qu’à leurs familles dans l’adversité.

Que les hommes et mes confrères m’accordent leur estime si je suis fidèle à mes promesses ; que je sois déshonoré et méprisé si j’y manque.

Quelle est la validation interne et la dimensionnalité de la version

française de la « Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25 », dans le

diagnostic de la dépression en soins primaires ?

Résumé

Introduction

Le diagnostic de dépression est difficile en ambulatoire. Les outils diagnostiques sont rarement utilisés par les médecins généralistes. La Hopkins Checklist Symptom en 25 questions (HSCL-25) est un outil clinique validé contre l’examen psychiatrique basé (selon les critères du DSM). Après une RAND/UCLA, la HSCL-25 a été sélectionnés comme le meilleur choix pour ses qualités combinées d’efficacité, de fiabilité et d’ergonomie. Elle a été traduite selon une procédure aller/retour basé sur méthode Delphi. La dernière phase de l’étude avait pour objectif de comparer les versions françaises de la HSCL-25 au « Patient State Examination version 9 »(PSE-9). Cette étude a pour objectif la validation interne et l’étude de la dimensionnalité de la HSCL-25 dans sa version française en pratique courante. Méthode

Etude quantitative de comparaison entre HSCL-25 et PSE-9, sur plusieurs centres médicaux, pour des patients adultes, après consentement, considérés ou non dépressifs par les 2 outils. Un patient est considéré comme « dépressif » si le score moyen HSCL-25 est supérieur ou égal à 1,75. Dans le groupe HSCL+, 1 patient sur 2 a réalisé le PSE-9 dans la semaine qui suivait le test HSCL-25. Dans le groupe HSCL-, 1 patient sur 16 a réalisé le PSE-9 dans un délai de 1 mois.

Résultats

Les patients inclus répondaient aux critères d’inclusion. L’étude de la consistance interne selon une analyse factorielle montre une dimension « anxiété » et une dimension « dépression ». Ces dimensions sont combinées pour donner un outil unidimensionnel. L’alpha de Cronbach est élevé à 0,93.

Conclusion

La HSCL-25 a été traduite selon une procédure garantissant sa stabilité. Son étude de validation en pratique courante trouve une haute valeur propre et une grande stabilité. Fiable et ergonomique, elle peut être utilisé aussi bien en recherche qu’en pratique courante dans les cabinets de Médecine Générale.

What is the internal validation and dimensionality in the

translation of HSCL-25 in French, in the diagnosis of depression

in primary care?

Abstract

Introduction

Diagnosis of depression is difficult and diagnostic tools are rarely used by GPs. The Hopkins Checklist Symptom in 25 items (HSCL-25) was retained to fill this gap. It is a clinical tool, validated against a psychiatric examination according to DSM major depression criteria. Following a RAND / UCLA, the HSCL-25 has been selected as the most efficient, reliable and ergonomic tool combined. The HSCL-25 has been translated into French using a forward/backward translation according a Delphi procedure. The last phase consisted in comparing HSCL-25 scale against Patient State Examination-9 version (PSE-9), it has confirmed the internal validation and dimensionality of the French HSCL-25 version in primary care.

Method

Adults’ patients who completed ethical consent were selected. Patients lived in Finistère (France), in 2015.

A patient is considered "depressive" if her/his mean HSCL-25 score is greater than or equal to 1.75. In the HSCL- group one in 16 patients have performed PSE-9 while in the HSCL + group, the ratio of 1 in 2.

Results

Patients included met the inclusion criteria. After removed duplicates and wrongly inclusion, 1126 patients were included among 1134. The factor analysis showed that HSCL-25 tool is a one-dimensional tool - which combined an anxiety and a depression dimensions - with a Cronbach alpha of 0.93.

Conclusion

The HSCL-25 scale has a high eigenvalue. It was a one-dimensional tool which combined items according anxiety and depression. This reliable tool will provide survey in primary care daily practice.

Table of content

BACKGROUND ... 14 METHOD ... 16 Inclusion criteria ... 17 Exclusion criteria ... 17 Location of study ... 17 Number of patients ... 19 Method of analysis ... 20 RESULTS ... 20Duration of the study ... 21

Flow chart ... 21

Population included and sample randomized ... 22

Dimensional structure and internal consistency ... 23

A factor analysis to determine the number of dimensions and the distribution of items on these dimensions ... 23

Study of the internal consistency of each dimension obtained ... 25

DISCUSSION ... 26 CONCLUSION ... 31 BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 33

BACKGROUND

Depression is one of the most common mental illness in France (1,2) and Europe (3,4). This syndromic disease combine multiple symptoms as sadness, loss of interest, loss of pleasure, feelings of guilt or low self-esteem, sleep or appetite disorders, fatigue, lack of concentration… and somatic disorders(5–7). In France and many other countries, depression is defined according to the diagnostic criteria of ICD-10 and DSM-V.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) depression affects 350 million people in the world (6). The prevalence varies between the different countries in Europe (8–10). The prevalence of depression is twice as high for women as for men.

Depression affects more than 3 million people in France. According to a survey published in 2012 of National Institute of Prevention and Education for Health (INPES), the prevalence is estimated to be between 5 and 12% of the whole population (7). Currently, nearly 8 million French people have experienced or will experience depression during their lifetime (11,12). And 7.5% of French people aged between 15 and 85 years old suffered from depression in the past 12 months (13).

Depression take a significant impact on emotional, social and occupational life (1). It is a major risk factor for suicide (14,15). France is one of the European countries with the highest rate of suicide mortality (16). Each year, more than 10,400 people die from suicide, e.g. one in fifty deaths in France (17).

Its management is multimodal, combining or not drugs treatments and psychotherapeutics activities.

In most European countries, General practitioners (GPs) are the port of call to diagnose and manage depressed patients(18–20). General practitioners are the first consulted, before psychiatrists and psychologists (21,22). GPs are present in 67% of the care paths and in half of the cases, they are the only one to take care (23–27).

Diagnosing major depression has a high specificity but low sensitivity in general practice (23). For the past 25 years, it is known to academic psychiatry and primary care that only

10-50% of depressed patients receive adequate treatment because of the difficulty and the inability to recognize depression. Less than one person in four suffering from depression consults a doctor, and is therefore diagnosed and treated appropriately (25,28,29). This may be related to the patient's reluctance to express symptoms and the variability in the symptomatology of depression (30). But another obstacle in depression recognition is that traditional psychiatric interviewing is not appropriate in primary care settings because it takes too long (31–35).

The European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN), member of the World Organization of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners / Family Physicians (WONCA), was established to promote and develop research in general medicine and primary care and to initiate and coordinate international research. In 2014, a systematic review of the literature validated 7 diagnostic tools for depression in primary care, comparing them to a psychiatric clinical examination according to DSM major depressive criteria (36,37). After a consensus method (RAND / UCLA), the “Hopkins Symptom Checklist in 25 items” (HSCL-25) taking the most combined efficiency, reliability and ease to use (36–41). The third phase, in December 2014, was the round translation of the HSCL-25 scale in French, according to a forward/backward Delphi procedure translation followed by a cultural check, in order to keep linguistic and meaning homogeneity from the original version.

The HSCL-25 is a self-rating scale on the existence and severity of both anxiety and depression symptoms during the preceding week, used to identify psychiatric illness in primary care. It includes 25 items: 10 about anxiety, 15 about depression. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The points are totalled and divided by 25. A 1-to-4 score is obtained. The patient is considered as a “probable psychiatric case” if the mean rating on the HSCL-25 is ≥ 1.55. A cut-off value of ≥ 1.75 is generally used for the diagnosis of major depression, defined as “a case, in need of treatment” (42).

The Present State Examination in its 9th version (PSE-9), or standardized psychiatric examination, is a comprehensive, systematized, semi-directed clinical interview. The PSE was developed in England by Wing et al. It explores, in 140 items, a large part of the psychiatric semiology (43). It is a standardized questionnaire realised by a psychiatrist or a professional specially trained to the psychiatric examination, which evaluates the mental state.

In Sweden, in 1993 a study of Nettlebladt & al aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the HSCL-25 scale in primary care daily practice. A survey of patients consulting GPs has been conducted in order to compare HSCL-25 against PSE-9. It reported a concordance of 86.7% (44).

This scale is not used by French GPs. A French survey based on the study of Nettlebladt & al has been decided.to determinate the external and internal validity of the French HSCL-25 version.

This part of the study was focused on the internal validation and the dimensionality of the French HSCL-25 version.

METHOD

The EA SPURBO (primary care, public health, Brest Cancer Registry in Western Brittany) research network team carried out a quantitative cross-validation study of HSCL-25 against PSE-9, in an adult population, in daily practice, in medical surgery. It was a multi-centered, rural and urban, comparative and non-inferiority study, with 2 groups.

The objective was the validation and characterisation of the French HSCL-25 scale version according to external and internal features.

In order to compare the HSCL-25 and the PSE-9 scoring, a specials investigators GPs team were training by a combined Gps and psychiatrist researchers team, to use HSCL-25 and PSE-9.

The study focused the result of HSCL-25 on the score greater than or equal to 1.75. According to the accuracy features of the HSCL-25, a patient is recognized depressed if his score is greater than or equal to 1.75. Conversely, if his score is strictly below the threshold of 1.75, the patient will not be recognized as depressed.

This part of the study focused the results on the internal validation and dimensionality of the French HSCL-25 scale in primary care daily practice.

Inclusion criteria

Adult patients older or equal than 18 years old (Legal age of majority in France), without age limit. Patients had to give their written ethical consent for participation in the study. Patient had to complete the HSCL-25 self-questionnaire and submit it to the investigating.

Exclusion criteria

In order to avoid puerperal depression in which the management is different, women with a reported pregnancy were not included in the study (45). As a puerperal depression needs a specific management. Adults consulting for a medical certificate were excluded as the research was focused on adults consulting for at least a medical condition in primary care. Psychotic patients were excluded. Patients requiring immediate acute care were excluded

Location of study

The recruitment was carried out in primary care, in the surgeries of the investigating practitioners belonging to the network of internship masters (MSU) of the University Department of General Medicine (DUMG) of Brest, included in the EA SPURBO Network. The population was according to the centres: urban, semi-rural and rural. The study was carried out in the North Brittany

In the waiting room patients had a leaflet explaining the study, an HSCL-25 scale and a consent form. The recruitment was made either spontaneously by the participants after reading the explanatory notice, or on proposal and after information by the GP investigator after information in the waiting room.

Table 1: HSCL-25 ITEMS

HSCL-2 ORIGINAL VERSION FRANCE N°

Choose the best answer for how you felt over the past week

Veuillez choisir la réponse qui décrit le mieux comment globalement vous vous sentiez toute la semaine dernière

1 Being scared for no reason Vous avez peur sans raison 2 Feeling fearful Vous vous sentez effrayé

3 Faintness Vous avez une sensation d’étourdisse- ment

4 Nervousness Vous vous sentez nerveux

5 Heart racing Vous avez l'impression que votre cœur bat anormalement vite 6 Trembling Vous avez la sensation de trembler

7 Feeling tense Vous vous sentez tendu 8 Headache Vous avez des maux de tête 9 Feeling panic Vous vous sentez paniqué 10 Feeling restless Vous vous sentez agité 11 Feeling low in energy Vous manquez d’énergie

12 Blaming oneself Vous ressentez une sensation de culpabilité 13 Crying easily Vous pleurez facilement

14 Losing sexual interest Vous ressentez un désintérêt pour la vie sexuelle 15 Feeling lonely Vous avez une sensation de solitude

16 Feeling hopeless Vous vous sentez désespéré 17 Feeling blue Vous avez le cafard

18 Thinking of ending one’s life Vous avez pensé à mettre fin à votre vie 19 Feeling trapped Vous vous sentez pris au piège

20 Worrying too much Vous vous inquiétez trop 21 Feeling no interest Plus rien ne vous intéresse 22 Feeling that everything is an effort Tout est un effort pour vous

23 Worthless feeling Vous avez le sentiment d’être bon à rien 24 Poor appetite Vous avez perdu l’appétit

25 Sleep disturbance Votre sommeil est perturbé

Number of patients

Two types of patient were possible:

§ Patient HSCL-25 score ≥1.75 or HSCL+ or positive, § Patient HSCL-25 score <1.75 or HSCL- or negative. Two groups have been defined:

§ a HSCL+ group § a HSCL- group.

A stratified randomization was performed in each group, with: § with a step on one out of two (1/2) in the HSCL+ group § with a step on one out of sixteen (1/16) in the HSCL- group. The selected randomized patients were offered an interview for PSE-9.

§ If the patient had a HSCL+, the PSE-9 was performed within one week of inclusion. § If the patient had a HSCL-, the PSE-9 was performed within one month after

inclusion.

For patients not randomly selected, the study was terminated. But all patients with a score of ≥ 1.75 were informed by the investigating physician, usually as potentially depressed, to initiate the necessary care with them GPs, according to the ethical principle and the ethical consent form.

According to Nettelbladt et al., the expected difference is of the order of 60% against 15%, in all cases at least 50% against 20%. With these assumptions and for a power of 90%, it was necessary to have measured at least 88 PSE-9 in HSCL+ group and 44 PSE-9 in HSCL-.group for randomised patients (44).

This required the recruitment of 880 patients without counting the follow-up patients, the frequency of which should not exceed 20%. 1100 patients had to be included in order to take account of follow-up patients. They were divided between the three semi-rural, urban and rural centres.

Method of analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out by statisticians

All patients were included in the analysis, except incorrectly included and duplicates (only the first consultation was taken into account).

The final analysis of the data was to be carried out after the database freeze at the end of the data review meeting.

The data had to be analyzed by the Data Management Unit (UGD) of the Brest CHRU.

The statistical analyzes had to be carried out with SAS software version 9.4 and R version 3.2.0.

The tests had to be carried out at the risk of first species alpha 5%.

The number of subjects was re-evaluated during the study due to the unexpected distribution of patients in both groups. The analyzes concerning the validation of the questionnaire were added: dimensionality and internal consistency.

A factor analysis was carried out to determine the number of dimensions of the HSCL-25 scale and the distribution of the items in each of these dimensions (main component analysis, factor analysis with varimax rotation) and a study of the internal consistency of Each dimension obtained (calculation of the alpha coefficient of Cronbach).

RESULTS

The study team consisted of 2 physician researchers, 3 Gps trained in the psychiatric examination using the PSE-9, 1 psychiatrist, 1 statistician, 20 general practitioners (divided into 3 geographical areas: urban, semi-rural and Rurales), 1 Data Manager and 1 Research Coordinator.

Duration of the study

The inclusion period was 20 weeks. The duration of participation for each patient was 1 week. The total duration of the study was 12 months. The study was conducted between 2015 and 2016.

Flow chart

The number of patients included, having passed HSCL-25, who were randomized to the PSE-9 group or not, and having passed the PSE-PSE-9, are shown in the flow chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow Chart

n=1 134

1126 patients included

HSCL25 < 1,75 n=886

Not PSE9 after randominsation n=831 PSE9 after randominsation n=55 PSE9 executed n=46 HSCL25 ≥1,75 n=240 PSE9 after randominsation n=118 PSE9 executed n=96

Not PSE9 after randominsation

n=122 Wrongly included:

n=2 Duplicates : n=6

1134 patients were selected: 2 patients were wrongly included and 6 were duplicates.

Among 1126 patients, a group of 886 patients HSCL- and a group of 240 patients HSCL+ were included.

Stratified randomisation:

According a pitch of 1/16, 55 patients were randomised in the HSCL- group. According a pitch of 1/2, 118 patients were randomised in the HSCL+ group.

Population included and sample randomized

The age and sex of included population is described in table 2 Table 2: Age and sex of included population

Variable Class Overall Population Group HSCL- Group HSCL+ P * Age N 1126 886 240 <0.001 Mean +/- SD 55,62 +/- 18,4 56,60 +/- 18,6 51,98 +/- 17,0 Median (q1-q3) 59 (42 – 70) 61 (42-72) 53 (38 - 66) Min-max 18-94 18-94 19-91 Sex Male 452 (40%) 390 (44%) 62 (26%) <0.001 Female 674 (60%) 496 (56%) 178 (74%) SD: Standard deviation

*obtained by Student t test for quantitative variables and Chi² test for qualitative variables The median age was 59 years old (42-70). The patients were aged between 18 and 94 years (table 2).

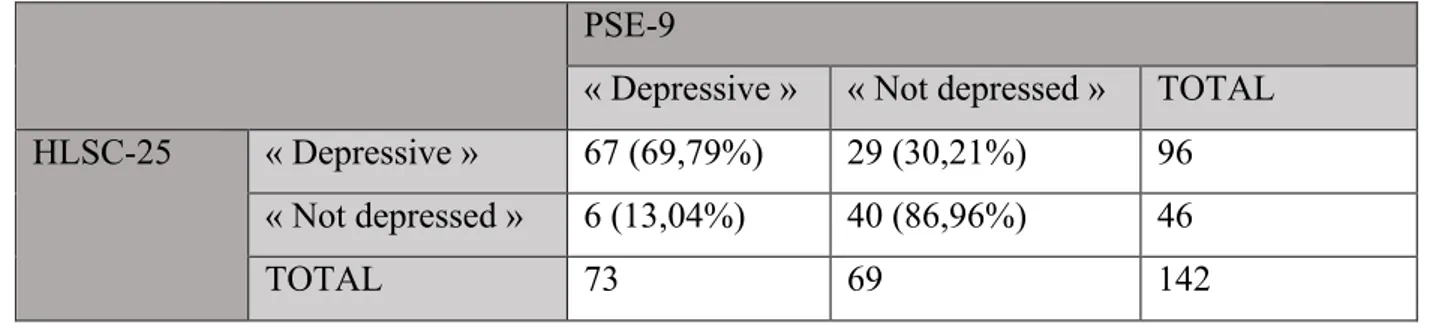

After randomization:

55 patients in the HSCL-25- group had to pass the PSE-9. • 46 patients performed the PSE-9, and 9 were follow-up. • 6 were positive to PSE-9 and 40 negative.

118 patients in the HSCL+ group had to pass the PSE-9.

• 96 patients performed the PSE-9, and 22 were follow-up. • 67 were positive to PSE-9 and 29 were negative.

Results are presented in the contingency table in Table 4. Table 4: Contingency table for HSCl-25 and PSE-9

PSE-9

« Depressive » « Not depressed » TOTAL HLSC-25 « Depressive » 67 (69,79%) 29 (30,21%) 96 « Not depressed » 6 (13,04%) 40 (86,96%) 46 TOTAL 73 69 142

Dimensional structure and internal consistency

A factor analysis to determine the number of dimensions and the distribution of items on these dimensions have been carried out.

Figure 2: Diagram of eigenvalues

The eigenvalue diagram shows the dimensional structure of the HSCL-25 scale questionnaire. Since the questionnaire contains 25 elements, it can have up to 25 dimensions. The first point of the graph indicates the amount of information provided by the first dimension. This point has a high eigenvalue. This first dimension brings a lot of information. The second point provides information on the second dimension. This point has a lower eigenvalue than the previous one. The difference between the first and second dimensions is very important. It therefore contains less information than the first dimension. There is a significant break in the curve after the first dimension. The diagram shows that there is only one dimension studied. It is confirmed that the french HSCL-25 is a one-dimensional tool.

5 10 15 20 25 02468 1 0 Factors Ei g e n v a lu e s

Study of the internal consistency of each dimension obtained

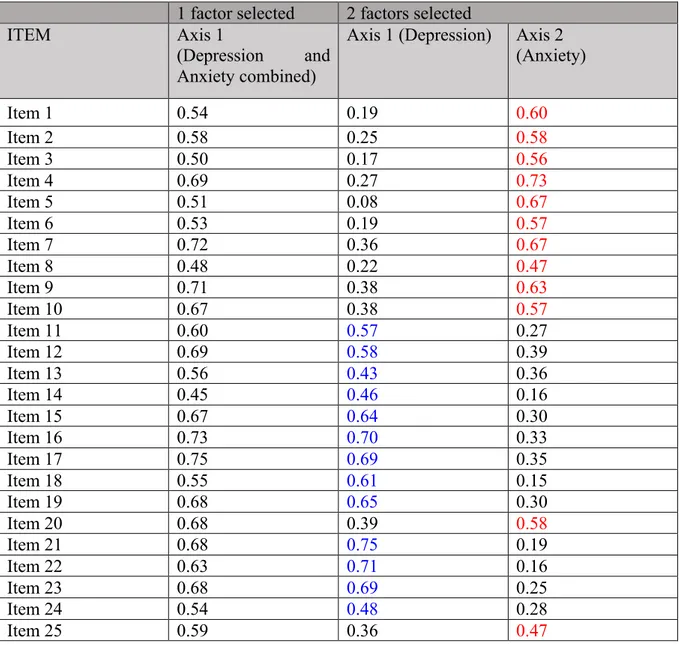

Table 5 presents the distribution that could be obtained if two dimensions were retained (as described in the literature: depression and anxiety). Note a different distribution of items between our study and the literature.

According to the factor analysis, a group 1 (corresponding to a "depression" dimension) is retained with items 11-19 and 21-24. And a group 2 (corresponding to an "anxiety" dimension) with items 1-10, 20 and 25.

In the literature, items related to anxiety are items of 1-10 and items of depression of 11-25. Table 5: Weight of items on each dimension according to factor analysis

1 factor selected 2 factors selected ITEM Axis 1

(Depression and Anxiety combined)

Axis 1 (Depression) Axis 2 (Anxiety) Item 1 0.54 0.19 0.60 Item 2 0.58 0.25 0.58 Item 3 0.50 0.17 0.56 Item 4 0.69 0.27 0.73 Item 5 0.51 0.08 0.67 Item 6 0.53 0.19 0.57 Item 7 0.72 0.36 0.67 Item 8 0.48 0.22 0.47 Item 9 0.71 0.38 0.63 Item 10 0.67 0.38 0.57 Item 11 0.60 0.57 0.27 Item 12 0.69 0.58 0.39 Item 13 0.56 0.43 0.36 Item 14 0.45 0.46 0.16 Item 15 0.67 0.64 0.30 Item 16 0.73 0.70 0.33 Item 17 0.75 0.69 0.35 Item 18 0.55 0.61 0.15 Item 19 0.68 0.65 0.30 Item 20 0.68 0.39 0.58 Item 21 0.68 0.75 0.19 Item 22 0.63 0.71 0.16 Item 23 0.68 0.69 0.25 Item 24 0.54 0.48 0.28 Item 25 0.59 0.36 0.47

Calculation of the Cronbach alpha coefficient

Table 6: The Cronbach Alpha Coefficient French HSCL-25 version

Dimension Cronbach’s alpha

1 dimension only

Item axis 1 0,93

2 dimensions selected according to factor analysis

Group 1 (items 11-19 et 21-24) 0,89 Group 2 (items 1-10, 20 et 25) 0,87

Table 6 shows the analysis that contains the value of the Cronbach alpha index.

The value is 0.93 in a one-dimensional analysis. This result was upper the minimum threshold of 0.7 (Nunnaly, 1978). This 0.7 tag is arbitrary, but widely accepted by the scientific community. Consequently, we can say that for this HSCL-25 scale composed of 25 items, we obtain a satisfactory internal coherence.

DISCUSSION

The HSCL-25 is a scale on the existence of both anxiety and depression symptoms. This survey studied the dimensionality and internal validity of the French version.

This depression diagnostic tool is confirmed as a one-dimensional scale. The reproducibility of the entire scale, according to Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93. This high result showed her high reproducibility in daily practice for outpatients; especially if the two subscales depression and anxiety are combined to converge towards the same objective.

The HSCL 25 is now the second validated self administered questionnaire in French to diagnose depression in primary care. The 4 DSQ was the first one but with two pitfalls: no

Cronbach’s alpha calculation for its reliability in French and no link with the gold standard diagnosis in psychiatry (DSM V). (46)

In primary care research, in daily practice, the multiplicity of users requires the use of tools with high stability.

Dimension Cronbach’s alpha

1 dimension only

Item axis 1 0,93

2 dimensions selected according to factor analysis

Group 1 (items 11-19 et 21-24) 0,89 Group 2 (items 1-10, 20 et 25) 0,87

2 dimensions retained according to the literature

Items « anxiété » (1-10) 0,85 Items « dépression » (11-25) 0,90 Table 7: The Cronbach Alpha Coefficient French HSCL-25 version

In the literature, there are other one-dimensional scales adapted for primary care. In the two-dimensional analysis, the Cronbach alpha index obtained in group 1 "depression" (items 11-19 and 21-24) is 0.89 (compared to 0.9 in the literature). The results in group 2 "anxiety" (items 1-10, 20 and 25) have a Cronbach coefficient at 0.87 (compared to 0.85 in the literature).

According to the psychometric properties, elements strongly correlated with each other probably indicate the measure of the same construct and this is exactly what we mean when we say of a scale that it is internally consistent. Moreover, this also refers to the idea that this scale measures a construct that is one-dimensional. Having a one-dimensional measurement increases the Cronbach’s alpha.

This scale is coherent (or homogeneous) because the elements (depression and anxiety) converge towards the same result, which increases Cronbach's alpha.

The Patient Satisfaction with Psychotropic (PASAP) scale has been shown to have good psychometric properties in a large bipolar population and therefore appears adequate to assess

the satisfaction of the treatment. The main component analysis was in favor of unidimensionality and a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.85. Its short length and good acceptability make it suitable for clinical research (47).

A study on pathological gambling among young people aged 15 to 19 was carried out in Italy using the SOGS-RA (Sychometric Evaluation of the South Oaks Gambling Screen: Revised for Adolescents) tool (48). The one-dimensional principal component of SOGS-RA was accepted, and with an acceptable internal consistency with a Cronbach alpha of 0.78.

The CLDSES (cholesterol-lowering diet self-efficacy scale) study of initial self-efficacy of cholesterol-lowering diets shows good psychometric properties with an internal coherence of 0.95 and factor analysis in favor of unidimensionality of the subscales (49).

When creating a scale, there are two possibilities: either it will be created to deal with a single theme e.g. one-dimensional or multidimensional.

The results depend therefore on how the scale is constructed and the goal sought. There seems to be no consensus on the unidimensional or multidimensional character of the scales, this depends on the character sought in the scale. In our case, we could have distinguished a "depression" dimension and an "anxiety" dimension, but the two themes are close enough to form a single dimension.

The literature finds the opposite of the bi-dimensional scales used in primary care.

The WHOQOL-Brief study showed a 5-domains model (psychological, physical, social relations, environment and level of independence) with adequate internal coherence. This study confirmed the multidimensional nature of the study (50).

The OPAS (Ocular Pain Assessment Survey) study was a survey on the assessment of eye pain, specifically designed to measure eye pain and quality of life. The intensity of eye pain was the primary outcome measure, and the secondary outcome measures were interference with quality of life, aggravating factors, associated factors, intensity of associated non-ocular pain and self-reported symptomatic relief. The factor analysis retained 6 subscales confirming multidimensionality. The coefficient Cronbach’s α was 0.83. OPAS is a reliable and responsive tool with strong psychometric and diagnostic properties in multidimensional quantification of the intensity of corneal and ocular surface pain and quality of life (51). The Hopkins questionnaire was originally developed for non-traumatized populations but was later adapted and widely used for the assessment of traumatized populations (52). HSCL-25

has been used to identify psychiatric disorders in primary care, family planning services, refugee populations and migrant populations (53).

Currently, the Hopkins symptoms checklist is widely used in primary care in various situations, such as psychological trauma after natural disasters, terrorist acts or among refugees for example (54).

One can cite the study "Mental health and psychosocial problems in the aftermath of the Nepal earthquakes: findings from a representative cluster sample survey" (55) carried out after the two major earthquakes in 2015 in Nepal. The purpose of this study was to examine the frequency of common mental health and psychosocial problems and their correlates as a result of earthquakes. The results were selected from several qualitative tools including only the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 for depression and anxiety. Tools also include the search for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD-Civilian Checklist), The consumption of dangerous alcohol (AUDIT-C), Symptoms of severe psychological distress (WHO / UNHCR Symptom Assessment Program), Suicidal Idea (Composite International Diagnostic Interview), Perceived needs (scale of perceived humanitarian needs (HESPER)), and functional impairment (scale developed locally). The overall results suggest that there were significant levels of psychological distress. The results highlight the importance of appropriate prevention strategies to reduce the risk of distressing disorder in post-disaster mental health care systems.

The study "Validity of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 amongst HIV-positive pregnant women in Tanzania" (56) was designed to validate the detection of depression in pregnant women with HIV in Tanzania by the Hopkins-25 (HSCL-25). The internal consistency of HSCL-25 (alpha 0.93) was adequate. HSCL-25 has demonstrated utility as a diagnostic tool for depression in primary care in Dar es Salaam, but the results are discussed because it has shown an inability to measure the severity of symptoms in this African cultural context and in developing countries where HIV is widespread. The French translation procedure was careful to use a method that preserved linguistic and meaning homogeneity, combining a forward-backward translation by Delphi procedure and a cultural control by consensus group.

With this method, avoiding discrepancies related to the biases of language and culture and context has preserved the homogeneity from the original. The HSCL-25 was adapted in the same way for French or English outpatients.

HSCL-25 was used in a longitudinal study "A Longitudinal Study of Psychological Distress and Exposure to Trauma Reminders After Terrorism" (57) on psychological distress 2.5 years after the terrorist attack on Utoya Island, (Norway), among survivors.

The tool is regularly used on the refugee population (52,54,58–60). The study "Mental disorder among refugees and the impact of persecution and exile: some findings from an out-patient population" (60) showed in particular the use of HSCL-25 refugees constitute a population at risk of mental disorders. Past traumatic stresses and current existence in exile are independent risk factors.

limitations of the study

The study population was multicentric, coming from rural, semi-rural and urban areas.

Concerning the sampling data, there was a double validation by the data manager and the research coordinator. Initially, all calculations were made on a theoretical prevalence of depression of 7% in the French adult population, but the prevalence obtained in the study was 21% in general practice. This observed difference in prevalence can be explained by over-recruitment, which can be explained by the White’s diagram. Based on a population of 1000 adults exposed to a health problem in the month, there were 750 people who could experience a health problem. Referring to the classical definition of primary care, only when a person consults with a health care practitioner begins primary care, about 250 of the 750 people with a health condition, or a quarter Population of departure (61). This phenomena can explains the focusing of health problems in daily practice surgeries

The difference is all the more important, as depressive syndrome is complex to diagnose. Britain has the highest rate of suicide in France (62), it is very likely that this is correlated with a depression rate greater than in the general French population.

The data manager to verify that all HSCL-25 questionnaires were complete limited selection bias. The psychiatrist checked that all the PSE-9 questionnaires were complete.

For Information bias, all data were collected (sampling data, HSCL-25 and PSE-9) were compiled into a computer database. At the end of the study, all information was checked one last time and the database was frozen for statistical work.

Confusion bias was limited as the self-administered questionnaire was completed by every patient without external influence. All responses collected during the PSE-9 interview were retrospectively monitored by the psychiatrist in a group meeting with the 3 reviewers.

General practitioners are faced with a difficulty in diagnosing depression by the multitude of symptoms. Screening is difficult because the depressive syndrome is masked by somatic complaints and emotional difficulties patients are poorly expressed. The Hamilton scale was little used because it was not adapted to a common practice in general practice. The HSCL-25 scale, divided into 2 sub-sections related to the presence and intensity of anxiety and depressive symptoms, will allow a self-completed questionnaire in 5-10 minutes by patients to screen for Patients suffering from psychiatry, in primary care. The efficacy, reliability and ergonomic qualities of HSCL-25 retained in phase 2 of the study will enable daily use in general practice. The use of HSCL-25 will allow a more important diagnosis in general medicine, which is one of the most common diseases (under diagnosed) in France. The main risk of depression is suicide. Aided by an adapted tool will allow the appropriate diagnosis and management of depressive patients. The applications of the HSCL-25 are multiple with an application for research in general practice, because her high reproducibility and one-dimensionality is focused on anxious and depressed outpatients. Her ease to use is an advantage, it increases the feasibility of survey but also It can be use in a perspective of teaching way.

CONCLUSION

The dimensional structure was studied, the eigenvalue diagram showed that the HSCL-25 is a one-dimensional tool.

A factorial analysis was carried out to test the internal coherence of each dimension. According to the factor analysis, a group 1 (corresponding to a "depression" dimension) is retained with elements 11-19 and 21-24. And a group 2 (corresponding to an "anxiety" dimension) with elements 1-10, 20 and 25. The literature defines 2 different groups: an "anxiety" group from 1 to 10 and a "depression" group from 11 to 25 In the analysis of the

Cronbach alpha index, the value retained was 0.93 in a one-dimensional analysis. The internal consistency of the scale is satisfactory. This scale is coherent, it has a high level of homogeneity.

These results validate the HSCL-25 scale compared to PSE-9 in its French version, in primary care for its reliability. As the HSCL-25 was selected for its efficiency, reliability and ergonomics this result will be useful in everyday practice in general practice in France. The HSCL 25 is the second validated French self administered questionnaire to diagnose depression in general practice (according to its reliability). It is the only one that has achieved a full reliability study. It could be widely used in primary care. The great usability of this tool will allow research in daily practice, for outpatients.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. M. Coldefy, C. Nestrigue. DREES. La prise en charge de la dépression dans les établissements de santé. Etude et Résultat. 2013; 860. Paris. 2. Ustün TB, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S, Mathers C, Murray CJL. Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. Br J Psychiatry. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2004; 184:386–92. 3. Ayuso-Mateos JL, Vázquez-Barquero JL, Dowrick C, Lehtinen V, Dalgard OS, Casey P, et al. Depressive disorders in Europe: prevalence figures from the ODIN study. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2001;179:308–16. 4. Prevalence, Severity, and Unmet Need for Treatment of Mental Disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Jama. 2004; 291(21),2581-90. 5. Organisation Mondiale de la Santé Europe. Définition de la dépression. 2017. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/fr/health-topics/noncommunicable- diseases/mental-health/news/news/2012/10/depression-in-europe/depression-definition. Cited 2017 Jan 5. 6. OMS. La dépression. Février 2017. N°369. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/fr/. Cited 2017 Feb 19. 7. Sapinho, D., Chan-Chee, C., Briffault, X., Guignard, R., & Beck, F. 2008. Mesure de l’épisode dépressif majeur en population générale: apports et limites des outils. Bulletin épidémiologique hebdomadaire, 35, 313-7. 8. INPES. La dépression en France (2005-2010): prévalence, recours au soin et sentiments d’information de la population. La Santé de l’Homme. 2012. n°421 201AD. 9. World Health Organization Europe. Data and statistics. 2017. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases/mental-health/data-and-statistics. Cited 2017 Feb 19. 10. King M, Nazareth I, Levy G, Walker C, Morris R, Weich S, et al. Prevalence of common mental disorders in general practice attendees across Europe. Br J Psychiatry. 2008 May 1;192(5):362–7. 11. World Health Organization Europe. La dépression en Europe. 2012. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/fr/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases/mental- health/news/news/2012/10/depression-in-europe/depression-in-europe-facts-and-figures. Cited 2017 Jan 5.12. Beck F, Guilbert P, Gautier A. Baromètre santé 2005. Edition INPES. 459-519. 13. Chan Chee C, Gourier-Fréry C, Guignard R, Beck F. The current state of mental health surveillance in France. Sante Publique (Vandoeuvre les Nancy, France). 2011;23 Suppl 6:S13-29. 14. Lejoyeux M, leon E RF. Prevalence and risk factors of suicide and attempted suicide. Encephale. 1994;20(5):495–503 15. Aouba, Péquignot, Camelin, Laurent, Jougla. DREES. La mortalité par suicide en France en 2006. Etudes et résultats. 2009;702. 16. Institut de Veille Sanitaire (InVS). Tentatives de suicide et suicides / Données de surveillance par pathologie / Santé mentale / Maladies chroniques et traumatismes / Dossiers thématiques / Accueil Tentatives de suicide et suicides / Données de surveillance par pathologie / Santé mentale / Maladies chroniques et traumatismes / Dossiers thématiques. Available from: http://invs.santepubliquefrance.fr/Dossiers- thematiques/Maladies-chroniques-et-traumatismes/Sante-mentale/Donnees-de-surveillance-par-pathologie/Tentatives-de-suicide-et-suicides. Cited 2017 Jan 5. 17. Beck, F., Guignard, R., Du Roscoät, E., & Saïas, T. Tentatives de suicide et pensées suicidaires en France en 2010. Bull Epidémiol Hebd. 2011;47, 488-492. 18. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H, et al. Psychotropic drug utilization in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scandinavica. 2004; 109-s420.55-64. 19. Dezetter A, Briffault X, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, et al. Factors Associated With Use of Psychiatrists and Nonpsychiatrist Providers by ESEMeD Respondents in Six European Countries. Psychiatr Services. 2011; 62.2.143-151. 20. Ani C, Bazargan M, Hindman D, Bell D, Farooq MA, Akhanjee L, et al. Depression symptomatology and diagnosis: discordance between patients and physicians in primary care settings. BMC Fam Pract. 2008; 3;9(1):1. 21. Starfield B. Global health, equity, and primary care. JABFM J Am Board Fam Med 2007;20(6):511–3. 22. Ho FY-Y, Yeung W-F, Ng TH-Y, Chan CS, Greenberg PE, Simon GE, et al. The Efficacy and Cost-Effectiveness of Stepped Care Prevention and Treatment for Depressive and/or Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep. 2016; 5;6:29281. 23. Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009; 374(9690):609–19. 24. Norton J, de Roquefeuil G, David M, Boulenger J-P, Ritchie K, Mann A. Prévalence des troubles psychiatriques en médecine générale selon le patient health questionnaire :

adéquation avec la détection par le médecin et le traitement prescrit. Encephale. 2009 ;35(6):560–9. 25. Ferrari AJ, Norman RE, Freedman G, Baxter AJ, Pirkis JE, Harris MG, et al. The burden attributable to mental and substance use disorders as risk factors for suicide: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e91936. 26. Favre Bonté J, Cecchin M LS. Episode dépressif caractérisé de l’adulte : prise en charge en premier recours. Recommandation de bonne pratique. Haute Autorité de Santé. 2014. 27. Lépine JP, Gastpar M, Mendlewicz J, Tylee A. Depression in the community: the first pan-European study DEPRES (Depression Research in European Society). Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;12(1):19–29. 28. Bagby RM, Ryder AG, Schuller DR, Marshall MB. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: Has the Gold Standard Become a Lead Weight? Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161(12):2163–77. 29. Haute Autorité de Santé. Conférence de consensus : la crise suicidaire : reconnaître et prendre en charge. 2000. Available from: https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/suicicourt.pdf 30. Jorm AF. Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000; 177:396–401. 31. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of Global Mortality and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030. Samet J, editor. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. 32. Sharp LK, Lipsky MS. Screening for depression across the lifespan: a review of measures for use in primary care settings. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(6):1001-8 33. Sartorius N, Ustün TB, Costa e Silva JA, Goldberg D, Lecrubier Y, Ormel J, et al. An international study of psychological problems in primary care. Preliminary report from the World Health Organization Collaborative Project on “Psychological Problems in General Health Care”. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(10):819–24. 34. Reynolds CF, Kupfer DJ. Depression and Aging: A Look to the Future. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(9):1167–72. 35. Eisinger P. Syndrome dépressif. EMC - Trait médecine AKOS. 2008;3(3):1–9. 36. Nabbe P, Le rest JY, Le Prielec A RE. Systematic literrature review : what validated tools are used to screen or diagnose depression in general practice ? European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN). 2012; 37. Nabbe P, Le Reste JY, Guillou-Landreat M, Munoz Perez MA, Argyriadou S, Claveria A, et al. Which DSM validated tools for diagnosing depression are usable in primary care

research? A systematic literature review. Eur Psychiatry. 2017 ;39:99–105. 38. E beck-R. Quel est l’outil de diagnostic de la dépression le plus approprié chez le patient adulte, en médecine générale en Europe, selon ses critère d’efficacité, de reproductivité et d’ergonomie ? Thèse de médecine. Faculté de Médecine. 2013. 39. P L. Consensis d’expets sur la traduction en Français d’une échelle d’auto-évaluation de la dépression, la “Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25” via une procédure Delphi et une traduction retour en Anglais. Thèse de médecine. Faculté de Médecine. Brest. 2015. 40. Hoeymans N, Garssen AA, Westert GP, Verhaak PFM. Measuring mental health of the Dutch population: a comparison of the GHQ-12 and the MHI-5. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004 7;2:23. 41. Patrice Nabbe, Le Reste JY, Le Prielec A, robertE, Czachowski S D. Depression and multimorbidity in family Medicine: systematic literature review : what valided tools are used to screen or diagnose depression in general practice ? Study FPDM 42. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A Self Report Symptom Inventory. Behavioral Science. 1974. Vol. 19,p. 1–15. 43. Muy A, Kang S, Chen L, Domanski M. Reliability of the Geriatric Depression Scale for use among elderly Asian Imigrants in the USA. Int psychogeriatrics IPA. 2003;15(3):253–71. 44. Nettelbladt P, Hansson L, Stefansson CG, Borgquist L, Nordström G. Test characteristics of the Hopkins Symptom Check List-25 (HSCL-25) in Sweden, using the Present State Examination (PSE-9) as a caseness criterion. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1993;28(3):130–3. 45. Institut National de Prévention et d'Education pour la Santé. Troubles émotionnels et psychiques des mères. Le vécu des femmes et des couples, leurs besoins. Fiche action 16. 2010. Available from: http://inpes.santepubliquefrance.fr/CFESBases/catalogue/pdf/1310-3p.pdf 46. Chambe J, Le Reste J-Y, Maisonneuve H, et al. Evaluating the validity of the French version of the Four-Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire with differential item functioning analysis. Fam Pract 2015; published online May 7. DOI:10.1093/fampra/cmv025. 47. Nordon C, Falissard B, Gerard S, Angst J, Azorin JM, Luquiens A, et al. Patient satisfaction with psychotropic drugs: Validation of the PAtient SAtisfaction with Psychotropic (PASAP) scale in patients with bipolar disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(3):183–90. 48. Colasante E, Gori M, Bastiani L, Scalese M, Siciliano V, Molinaro S. Italian Adolescent Gambling Behaviour: Psychometric Evaluation of the South Oaks Gambling Screen: Revised for Adolescents (SOGS-RA) Among a Sample of Italian Students. J Gambl Stud.

2014; 6;30(4):789–801. 49. Burke, L. E., Kim, Y., Senuzun, F., Choo, J., Sereika, S., Music, E., & Dunbar-Jacob, J. (2006). Evaluation of the shortened cholesterol-lowering diet self-efficacy scale. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2006; 5(4), 264-274. 50. Oliveira SEH, Carvalho H, Esteves F. Toward an understanding of the quality of life construct: Validity and reliability of the WHOQOL-Bref in a psychiatric sample. Psychiatry Res. 2016; 30;244:37–44. 51. Qazi Y, Hurwitz S, Khan S, Jurkunas U V., Dana R, Hamrah P. Validity and Reliability of a Novel Ocular Pain Assessment Survey (OPAS) in Quantifying and Monitoring Corneal and Ocular Surface Pain. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(7):1458–68. 52. De Fouchier C, Blanchet A, Hopkins W, Bui E, Ait-Aoudia M, Jehel L. Validation of a French adaptation of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire among torture survivors from sub-Saharan African countries. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2012;3. 53. Syed HR, Zachrisson HD, Dalgard OS, Dalen I, Ahlberg N. Concordance between Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-10) and Pakistan Anxiety and Depression Questionnaire (PADQ), in a rural self-motivated population in Pakistan. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:59. 54. Schock K, Böttche M, Rosner R, Wenk-Ansohn M, Knaevelsrud C. Impact of new traumatic or stressful life events on pre-existing PTSD in traumatized refugees: results of a longitudinal study. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016;7:32106. 55. Kane JC, Luitel NP, Jordans MJD, Kohrt BA, Weissbecker I, Tol WA. Mental health and psychosocial problems in the aftermath of the Nepal earthquakes: findings from a representative cluster sample survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;1–10. 56. Kaaya SF, Fawzi MCS, Mbwambo JK, Lee B, Msamanga GI, Fawzi W. Validity of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 amongst HIV-positive pregnant women in Tanzania. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(1):9–19. 57. Glad KA, Hafstad GS, Jensen TK, Dyb G. A Longitudinal Study of Psychological Distress and Exposure to Trauma Reminders After Terrorism. Psychol Trauma Theory, Res Pract Policy. 2016. 58. Sonne C, Carlsson J, Bech P, Vindbjerg E, Mortensen EL, Elklit A. Psychosocial predictors of treatment outcome for trauma-affected refugees. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016;7:30907. 59. Sonne C, Carlsson J, Bech P, Elklit A, Mortensen EL. Treatment of trauma-affected refugees with venlafaxine versus sertraline combined with psychotherapy - a randomised study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):383. 60. Lavik NJ, Hauff E, Skrondal A, Solberg O. Mental disorder among refugees and the

impact of persecution and exile: some findings from an out-patient population. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169(6):726–32. 61. Budowski M, Gay B. Comment former les futurs généralistes ? De la difficulté pour les généralistes de nombreux pays à enseigner dans les écoles ou les facultés de médecine. La Revue Exercer. 2005;75 142-44 62. Kopp-Bigault C, Walter M, Thevenot A. The social representations of suicide in France: An inter-regional study in Alsace and Brittany. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;62(8):737–48.

PELLEN Anne-Laure

What is the internal validation and dimensionality in the translation of HSCL-25 in French, in the diagnosis of depression in primary care?

Thèse Médecine Brest 2017

RESUME :

Diagnosis of depression is difficult and diagnostic tools are rarely used by GPs. The Hopkins Checklist Symptom in 25 items (HSCL-25) was retained to fill this gap. It is a clinical tool, validated against a psychiatric examination according to DSM major depression criteria. Following a RAND / UCLA, the HSCL-25 has been selected as the most efficient, reliable and ergonomic tool combined. The HSCL-25 has been translated into French using a forward/backward translation according a Delphi procedure. The last phase consisted in comparing HSCL-25 scale against Patient State Examination-9 version (PSE-9), it has confirmed the internal validation and dimensionality of the French HSCL-25 version in primary care.

Adults’ patients who completed ethical consent were selected. Patients lived in Finistère (France), in 2015.

A patient is considered "depressive" if her/his mean HSCL-25 score is greater than or equal to 1.75. In the HSCL- group one in 16 patients have performed PSE-9 while in the HSCL + group, the ratio of 1 in 2.

Patients included met the inclusion criteria. After removed duplicates and wrongly inclusion, 1126 patients were included among 1134. The factor analysis showed that HSCL-25 tool is a one-dimensional tool - which combined an anxiety and a depression dimensions - with a Cronbach alpha of 0.93.

The HSCL-25 scale has a high eigenvalue. It was a one-dimensional tool which combined items according anxiety and depression. This reliable tool will provide survey in primary care daily practice.

MOTS CLES :

Hopkins Checklist Symptom in 25 items (HSCL-25) Patient State Examination-9 version (PSE-9) One dimensional tool

Depression Anxiety

Cronbach alpha 0,93

JURY :

PRÉSIDENT DU JURY Pr. Jean Yves LE RESTE MEMBRES DU JURY Dr. Patrice NABBE

Pr. Bernard LE FLOC’H Florence GATINEAU

DATE DE SOUTENANCE :

ADRESSE DE L’AUTEUR :