HAL Id: tel-01835434

https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01835434

Submitted on 11 Jul 2018HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-entific research documents, whether they are pub-lished or not. The documents may come from teaching and research institutions in France or abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires publics ou privés.

Contribution to the surveillance and measurement of

physical activity and sedentary behaviors

Fabien Rivière

To cite this version:

Fabien Rivière. Contribution to the surveillance and measurement of physical activity and seden-tary behaviors. Santé publique et épidémiologie. Université de Lorraine, 2017. English. �NNT : 2017LORR0354�. �tel-01835434�

AVERTISSEMENT

Ce document est le fruit d'un long travail approuvé par le jury de

soutenance et mis à disposition de l'ensemble de la

communauté universitaire élargie.

Il est soumis à la propriété intellectuelle de l'auteur. Ceci

implique une obligation de citation et de référencement lors de

l’utilisation de ce document.

D'autre part, toute contrefaçon, plagiat, reproduction illicite

encourt une poursuite pénale.

Contact : ddoc-theses-contact@univ-lorraine.fr

LIENS

Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 122. 4

Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 335.2- L 335.10

http://www.cfcopies.com/V2/leg/leg_droi.php

École Doctorale BioSE (Biologie-Santé-Environnement) Thèse

Présentée et soutenue publiquement pour l’obtention du titre de DOCTEUR DE l’UNIVERSITÉ DE LORRAINE

Mention : « Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé » Par Fabien Rivière

Titre :

Contribution à la surveillance et à la mesure de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires

Date : 13 décembre 2017 Membres du jury

Rapporteurs :

Monsieur Georges Baquet MCU, EA 7369 UrePSSS, Faculté des Sciences du Sport et de l'Education Physique, Université de Lille 2, Lille, France.

Mme Caroline Terwee Associate professor in Measurement at the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics and the EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Examinateurs :

Mme Barbara Ainsworth, Regents Professor, School of Nutrition and Health Promotion, College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA. Co-directrice de thèse

Mr Sébastien Chastin, Senior Research Fellow, Physiotherapy, School of Health and Life Sciences, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, Scotlands, UK.

Mr Serge Hercberg, PU-PH, INSERM UMR1153, Centre de Recherche en Épidémiologie et Statistique Sorbonne Paris Cité (CRESS), Equipe de Recherche en Epidémiologie Nutritionnelle (EREN), Université Paris Descartes, Paris, France.

Mme Aurélie Van Hoye MCU, EA 4360 APEMAC, Université de Lorraine, Nancy, France. Mme Anne Vuillemin, PR, LAMHESS, Université Côte d’Azur, Nice, chercheur associée EA 4360 APEMAC, Université de Lorraine, Nancy, France. Directrice de thèse

EA 4360 APEMAC « Maladies chroniques, santé perçue et processus d'adaptation. Approches épidémiologiques et psychologiques », Faculté de Médecine, Université de Lorraine, 9 avenue de la Forêt de Haye, CS 50184, 54505 Vandœuvre-Lès-Nancy Cedex.

Acknowledgements

I am truly thankful to my supervisors, Anne Vuillemin and Barbara Ainsworth for their valuable support and guidance throughout the thesis, and just as important -if not more- their proximity and kindness. My PhD experience had ups and downs, and to say that this thesis wouldn’t had been possible without you is an overstatement. Thank you for pushing me till the end. I own this thesis to you.

I would also like to thank the jury members for offering me their expertise and time.

Résumé français

Revue de la littérature

La surveillance est un élément central pour la prise de décision en matière de santé publique. La surveillance de la santé publique est généralement considérée comme étant le recueil systématique et continu de données pertinentes, ainsi que leur consolidation et leur évaluation efficaces, s'accompagnant de la diffusion rapide des résultats aux personnes concernées, en particulier celles en mesure d'agir. La surveillance de la santé et de ses déterminants permet ainsi d’identifier les besoins et de définir les actions de santé prioritaires (Macera et Pratt, 2000, Lee, 2010).

L’activité physique et la sédentarité sont des déterminants majeurs de la santé et de la qualité de vie et, au regard de la prévalence des maladies non transmissibles, associées avec un trop faible niveau d’activité physique et une trop grande sédentarité, la surveillance de ces comportements et des maladies auxquelles ils sont associés paraît indispensable. L’activité physique est un comportement qui implique le mouvement humain et qui résulte en des caractéristiques physiologiques incluant une dépense énergétique (Pettee Gabriel et al., 2012). Un individu est caractérisé comme physiquement actif lorsque celui-ci respecte les recommandations sur l’activité physique. A l’inverse, lorsqu’un individu ne respecte pas ces recommandations, on parle d’individu inactif ou d’insuffisamment actif. Parfois confondu avec

l’inactivité physique, le comportement sédentaire se définit « comme une situation d’éveil caractérisée par une dépense énergétique ≤ 1,5 METs en position assise, inclinée ou allongée » (Tremblay et al., 2017).

Récemment, l’Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail (Anses), saisie par la Direction générale de la santé, a proposé de nouvelles recommandations (intégrant de nouveaux repères de pratique), synthétisées dans le tableau ci-dessous (Anses, 2016).

Catégories

d’âge Activité physique (AP) Recommandations Comportements sédentaires (CS)

Enfants

0-5 ans 1 Au moins 3 heures d’AP (180 min) dans la journée ou 15 minutes par heure (pour 12 heures d'éveil) ;

2 L’AP doit se composer d’activités motrices variées et de préférence ludiques.

3 Limiter la durée des CS et passer moins d’1h en continu dans des activités sédentaires ;

4 Eviter l’exposition aux écrans avant 2 ans et limiter l'exposition à moins d’1h/jr entre 2 et 5 ans.

Enfants

6-11 ans 5 6 Au moins 60 min/jr d’APME ;Dont au moins 3 séances d’au moins 20 minutes d'une AP d’intensité élevée (jours non consécutifs), et au moins 3 séances d’au moins 20 minutes d'une AP basée sur le travail musculo-squelettique (jours non consécutifs).

7 Limiter la durée des CS ;

8 Passer moins de 2h consécutives dans des CS ;

9 Limiter le temps de loisir passé devant un écran à 60 min/jr jusqu’à 6 ans et 120 min/jr jusqu’à 11 ans.

Adolescents

12-17 ans 10 11 Au moins 60 min/jr d'APME ;Dont au moins 3 séances de 20 min/semaine d'AP à intensité élevée (jours non consécutifs) ; et 3 séances de 20 min/semaine d'AP basée sur le travail musculo-squelettique (jours non consécutifs).

12 Limiter les périodes de sédentarité et d'inactivité à moins de 2h consécutives en position assise ou semi-allongée

Adultes

18-65 ans 13 Au moins 30 min/jr d’APME cardio-vasculaire. Des bénéfices supplémentaires sur la santé peuvent être obtenus avec une pratique de 45 à 60 min. Les AP peuvent être fractionné en périodes de 10 min minimales. Ces AP devraient être répétées au moins 5 jr/semaine, et si possible tous les jours ;

14 1 à 2 fois par semaine des AP de renforcement musculaire contre résistance ;

15 Les étirements doivent être réalisés régulièrement, au minimum 2 à 3 fois par semaine

16 Réduire le temps total quotidien passé en position assise, autant que faire se peut ;

17 Interrompre les périodes prolongées passées en position assise ou allongée, toutes les 90 à 120 min, par une AP de type marche de quelques minutes (3 à 5), accompagnée de mouvements de mobilisation musculaire.

Séniors

+65 ans

1

Au moins 30 min/jr d’AP cardio-vasculaires d’intensité modérée, au moins 5 fois par semaine ; ou 15 min par jour d’AP cardio-respiratoires d’intensité élevée, au moins 5 fois par semaine ; ou une combinaison d’APME sachant que 1 min d’AP d’intensité élevée équivaut à 2 min d’AP d’intensité modérée ;2

APME de renforcement musculaire 2 jr/semaine ou plus, de préférence non consécutifs.3

Limiter le temps total quotidien passé assis ou allongé ;‐ Fractionner le temps passé à des activités

sédentaires

La surveillance des comportements sédentaires et de l’activité physique en population générale est primordiale, notamment pour en évaluer la prévalence, la comparer aux repères de pratique conseillés, et la confronter aux données de santé. Les études de surveillance sont par ailleurs essentielles à l’élaboration des politiques nationales, ainsi qu’à l’évaluation des stratégies de promotion de l’activité physique et de prévention des comportements sédentaires. Toutefois, la mise en place d’études de surveillance fait face à certaines difficultés. Une difficulté majeure réside dans la capacité à obtenir une mesure précise de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires. Différents outils existent pour mesurer ces comportements, présentant différents avantages et inconvénients, et dont la qualité est essentielle pour obtenir des données pertinentes.

La fiabilité, la validité et la sensibilité des instruments sont des éléments à prendre en considération lors du choix de l’outil (Terwee et al., 2012). La fiabilité correspond à la reproductibilité d’une méthode c’est à dire à sa capacité à fourni un résultats identiques lorsque la méthode est utilisée à plusieurs reprises dans un même contexte, par la même personne ou par des personnes différentes. La validité réfère à la capacité de l’instrument à mesure ce qu’il est sensé mesurer. La sensibilité représente la capacité de l’instrument à détecter un changement au cours du temps. Parce que l’activité physique et les comportements sédentaires sont des comportements complexes et ubiquitaires, aucun instrument ne peut mesurer toutes leurs dimensions.

De ce fait, l’objectif de cette thèse était d’étudier l’état de la surveillance de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires, en particulier dans le contexte Français, et de contribuer à enrichir les connaissances concernant la mesure de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires.

Contributions personnelles

Pour contribuer à la surveillance et la mesure de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires cette thèse repose sur 4 articles, répartis dans l’un des deux axes de recherche ci-dessous. A ce jour, 2 articles ont été publiés dans des revues internationales à comité de lecture, et 2 ont été soumis à des revues pour publication.

Axis 1. Surveillance de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires

Etude 1. Rivière F., Escalon H., Duché P., Drouillet-Pinard P., Vuillemin A. National surveillance of physical and sedentary behaviors in France. (Submitted)

Etude 2. Aucouturier J., Ganière C., Aubert S., Riviere F., Praznoczy, C., Vuillemin A.,

Tremblay M.S., Duclos M., Thivel D. Results from the first French Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Adolescents (2016). Journal of Physical Activity

and Health. In press.

Axis 2. Mesure de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires

Etude 3. Rivière F., Aubert S., Yacoubou Omorou A., Ainsworth B.E., Vuillemin A. Content comparison of sedentary behavior questionnaires: a systematic review.

(Submitted).

Etude 4. Rivière, F., Widad, F. Z., Speyer, E., Erpelding, M. L., Escalon, H., Vuillemin, A.

(2016). Reliability and validity of the French version of the global physical activity questionnaire. Journal of Sport and Health Science. In Press.

Axe 1. Surveillance de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires.

Etude 1. Surveillance française de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires.

Position du problème : Les études de surveillance sont essentielles à l’élaboration des politiques

nationales et à l’évaluation des stratégies de promotion de l’activité physique et de prévention des comportements sédentaires. Ce travail a pour objectif de présenter les études nationales françaises disposant de données sur l’activité physique et la sédentarité ainsi que les principaux résultats.

Méthode : Les enquêtes nationales sur l’activité physique et la sédentarité ont été identifiées à

partir des revues existantes sur le sujet et des sites informatiques des organismes de santé publique français. Les rapports des études ont été analysés et complétés par les informations recueillies auprès des porteurs des études. Les caractéristiques suivantes ont été discutées : la méthode d’échantillonnage, le déroulement de l’étude, les outils de mesure, les niveaux d’activité physique, et les comportements sédentaires.

Résultats : 6 enquêtes réalisées entre 2005 et 2016 ont permis de comparer les comportements

de la population au regard des recommandations, parmi lesquelles 4 incluaient des enfants et adolescents âgés de 3 à 17 ans, et toutes des adultes âgés de 18 à 79 ans. Selon les études, entre 63 et 79% des adultes, et entre 30 et 43% des adolescents âgés de 15 à 17 ans atteignaient les recommandations françaises en matière d’activité physique. Les adultes ont reporté une durée moyenne du temps passé assis de l’ordre de 4h40 par jour. Les plus jeunes ont reporté un temps moyen passé devant un écran (télévision, ordinateur, et jeux vidéo) allant de 2h12 (3-10 ans) à 3h50 par jour (15-17 ans). De nombreuses différences ont été observées quant au nombre d’items, la période de rappel, et les caractéristiques mesurées avec les différents questionnaires. Les questionnaires utilisés auprès des enfants ne permettent pas de comparer les résultats obtenus avec les niveaux recommandés. Les enquêtes n’étant pas reproduites dans le temps ou les questionnaires utilisés étant différents, la comparaison des résultats au cours du temps est difficile.

Conclusion : Un système de surveillance constitué de mesures répétées identiques doit être mis

en place pour permettre d’observer l’évolution de l’activité physique et la sédentarité et d'évaluer l’efficacité des stratégies de santé publique.

Etude 2. Résultats de la première Report Card française sur l’activité physique des enfants et des adolescents.

Position du problème: De nombreux pays publient périodiquement une Report Card sur

l’activité physique des enfants et adolescents. Ce papier présente les résultats de la 1ère Report Card Française et permet d’évaluer les politiques et les actions mises en œuvre pour faciliter la pratique d’activité physique chez les jeunes.

Méthode: Une recherche à été effectuée pour identifier les bases de données nationales

permettant de renseigner sur les 8 indicateurs de la Report Card. Chacun des indicateurs s’est ensuite vu attribuer une note après concertation du collectif d’experts. Cette évaluation repose sur l’examen des statistiques et données disponibles, et permet d’attribuer un score au regard du système utilisé par l’ensemble des pays, allant de A (81-100 % des enfants et adolescents) à F (0-20 % des enfants et adolescents), ainsi que NC (pour désigner le manque de données).

Resultats: Le groupe d’expert a attribué les scores suivants: Niveau d’activité physique: INC;

Rôle des fédérations sportives: D; Transports actifs: D; Comportements sédentaires: D; L’environnement familial et social: INC; Place de l’école et de l’éducation physique: B; Les espaces de jeu et l’urbanisation: INC; Implcation gouvernementale et institutionnelle : INC. Conclusions: Les résultats de ce travail révèlent que peut d’enfants et adolescents atteignent le niveau d’activité physique recommandé, et que les efforts doivent être poursuivis pour augmenter l’activité physique des jeunes. Différents indicateurs n’ont pu être évaluer par manque de données, davantage de source de données sont donc nécessaires et peuvent nécessiter la mise en place de nouvelles études.

Axe 2. Mesure de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires

Etude 3. Comparaison du contenu des questionnaires portant sur les comportements sédentaires : une revue systématique.

Position du problème: Les comportements sédentaires ont des effets sur la santé pouvant varier

en fonction de leurs caractéristiques (ex: le type de comportement, leur durée, le contexte). Au cours des 10 dernières années, un nombre croissant de questionnaires mesurant les comportements sédentaires a été développé; entrainant de la confusion et un manque de clareté quant aux caractéristiques des comportements sédentaires qu’ils mesurent. De ce fait, l’objectif de ce travail était d’examiner le contenu des questionnaires portant sur les comportements sédentaires.

Méthode: Quatre bases de données ont été interrogées pour identifier les questionnaires publiés

avant le 1er janvier 2016. En respectant les critères d’inclusion, 82 articles (sur 1369 identifiés) ont été inclus, pour un total de 60 questionnaires. Pour chaque questionnaire, les caractéristiques des comportements sédentaires étaient identifiés et analysés.

Résultats: La plupart des questionnaires mesuraient Quand le comportement a lieu (n=55), la

Posture associée (n=54), Pourquoi il a lieu (n=46), and le Type (n=45); 20 questionnaires s’intéressaient à l’Environnement, 11 au context Social, et seulement 2 questionnaires prenaient en compte l’Etat de santé physique et mental et les Comportements associés (ex: fumer, manger). Tous les questionnaires, sauf 2, mesuraient le temps passé dans des comportements sédentaires, 17 mesuraient la fréquence de ces comportements, et 6 le nombre d’interruptions. Les caractéristiques qui sont le plus souvent mesurées sont ‘être assis’, ‘TV’, et ‘ordinateur’, identifiés dans 90, 65 et 55% des questionnaires, respectivement. A l’inverse, de nombreuses caractéristiques ne sont souvent pas mesurées.

Conclusions: En apportant un éclairage nouveau sur le contenu des questionnaires mesurant les

comportements sédentaires, cette revue aide à sélectionner le questionnaire approprié et permet de guider le développement de nouveaux questionnaires afin de mesurer les caractéristiques qui sont pour l’instant très peu mesurer par les questionnaires.

Etude 4. Fiabilité et validité du questionnaire mondial sur la pratique d’activités physiques.

Position du problème: Le questionnaire mondiale de l’activité physique (GPAQ) a été utilisé

pour mesurer l’activité physique et le temps assis en France, mais aucune étude n’a testé ses propriétés psychométriques. L’objectif de cette étude était d’examiner la fiabilité et la validité du GPAQ, en comparaison avec la version française du questionnaire international de l’activité physique (IPAQ) et des accéléromètres, en population générale.

Methode: La population d’étude (n=92) regroupe des étudiants et personnels de l’Université de

Lorraine, à Nancy, France. Les participants ont complété le GPAQ et l’IPAQ, à deux reprises, avec 7 jours d’intervalles, et ont porté pendant 7 jours un accéléromètre (Actigraph GT3X). La fiabilité et la validité du GPAQ ont été testés en utilisant les coefficients de corrélations intra-classe (ICC) et de Spearman pour les variables quantitatives, et les coefficients Kappa et Phi pour les variables qualitatives. La validité a également été examinée à l’aide de graphiques de Bland-Altman.

Résultats: Les résultats ont montré une fiabilité (ICC=0.37-0.94; Kappa=0.50-0.62), et validité

en comparaison de l’IPAQ (Spearman r=0.41-0.86) faibles à bonnes, mais une faible validité en comparaison des accéléromètres (Spearman r=-0.22-0.42). Les limites de concordance entre le GPAQ et les accéléromètres étaient importantes, avec des différences allant de 286.5 minutes par jour, à 601.3 minutes par jour.

Conclusions: La version française du GPAQ fait preuve de fiabilité et validité limitées, mais

acceptables au regard des autres questionnaires actuellement utilisés. Le GPAQ peut être utilisé pour mesurer l’activité physique et le temps assis en population française.

Discussion

Axe 1. Surveillance de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires

Cette thèse identifie un certain nombre de besoins et d’opportunités pour améliorer le système de surveillance de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires en France. Les études 1 et 2 ont ainsi identifié certaines limites impactant la qualité des données récoltées. Les études de surveillance reposent sur l’utilisation de questionnaire pour mesurer l’activité physique et les comportements sédentaires en population générale. Cependant, différents questionnaires ont été utilisés, et des modifications ont été effectuées pour certains d’entre eux, ce qui limite la comparaison des résultats entre les études et le suivi de l’évolution de ces données. Par ailleurs, les recommandations internationales et françaises préconisent différents types d’activité physique, dont les activités aérobics, de renforcement musculaire, et de souplesse; mais les études françaises ne mesuraient que les activités d’endurance, ne permettant pas d’estimer le pourcentage de la population respectant les valeurs seuils pour les activités de renforcement musculaire et de souplesse. D’autre part, le choix des outils de mesure rendait difficile l’estimation du pourcentage des enfants et adolescents qui respectent les recommandations concernant les activités physiques aérobics, comme le montre le Report Card. Parmi les limites, ces travaux soulignent également que la manière dont les données ont été analysées ne permet pas d’estimer le pourcentage de jeunes ayant un temps assis en deçà des valeurs recommandées. Les différentes méthodes d’analyse utilisées par chaque étude limitent également les comparaisons entre ces études.

Axe 2. Mesure de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires

L’étude 3 portant sur l’évaluation des propriétés psychométriques du GPAQ met en évidence une bonne reproductibilité du questionnaire, mais une validité limitée, bien que similaire aux résultats de validité des questionnaires de l’activité physique généralement observées dans la littérature. L’étude 4, évaluant le contenu des questionnaires des comportements sédentaires permet d’observer une grande diversité quant à ce que les questionnaires mesures, avec un nombre négligeable de caractéristiques des comportements sédentaires qui ne sont pas mesurés par les quesitonnaires existant. En conséquence, de nouveaux questionnaires doivent être développés, ou d’autre méthode de mesure doivent être utilisées pour mesurer ces caractéristiques, telles que EMA.

Conclusions

En conclusion, les travaux réalisés durant cette thèse permettent de formuler des recommandations visant à améliorer la surveillance de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires en France :

La surveillance de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires doit reposer sur des mesures standardisées et répétées ;

Les éléments clés des protocoles de collecte données, incluant les questionnaires d’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires, le mode d’administration des enquêtes, la période d’enquête, et les indicateurs utilisés doivent être standardisés ;

Les propriétés psychométriques des instruments utilisés doivent être testés dans les populations d’intérêts ;

Le choix de l’instrument de mesure doit être fait en adéquation avec les indicateurs désirés ;

Le système de surveillance doit non seulement fournir des informations sur l’évolution de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires, mais également fournir des informations sur les facteurs influençant l’activité physique et les comportements sédentaires, tels que l’environnement social et physique, et les politiques publiques.

Cette thèse concorde avec la stratégie sur l’activité physique pour la Région européenne de l’OMS 2016-2025 , et avec le plan global d’action sur l’activité physique de l’OMS pour la période 2018-2030. La stratégie et le plan d’action de l’OMS encouragent les états membres à renforcer la surveillance de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires à tous âges et dans tous les milieux, pour suivre les évolutions, et évaluer les politiques publiques. Dans le cadre de son plan d’action, l’OMS va soutenir les états membres dans leurs actions, ce qui peut représenter une opportunité pour les institutions de santé publique française d’améliorer le système de surveillance de l’activité physique et des comportements sédentaires en tenant compte des recommandations exprimées au cours de cette thèse.

Table of content

List of tables ... 4 List of figures ... 5 Publications ... 6 Communications ... 7 Abbreviations ... 8 Chapter 1. Introduction ... 9 Context ... 9

Research aims and questions ... 11

Research studies ... 12

Thesis outline ... 13

Chapter 2. Literature review ... 14

1 Physical activity and sedentary behaviors: concepts and definitions ... 14

1.1 Definitions of physical activity ... 14

1.2 Terms used in the measurement of physical activity ... 14

1.2.1 Intensity ... 15

1.2.2 Duration ... 17

1.2.3 Frequency ... 18

1.2.4 Mode ... 19

1.3 Definition of sedentary behaviors ... 19

1.4 Terms used in the measurement of sedentary behaviors ... 20

1.4.1 Sedentary time ... 20

1.4.2 Interruptions in sedentary time ... 21

1.4.3 Frequency of sedentary bouts ... 22

1.4.4 Mode of sedentary behaviors ... 22

1.5 Conceptual models of physical activity and sedentary behaviors ... 22

1.5.1 Measurement model for physical activity and energy expenditure (LaMonte and Ainsworth, 2001) ... 23

1.5.3 Taxonomy of sedentary behaviors ... 26

1.5.4 ALPHABET project ... 27

1.6 Summary ... 27

2 Measurement of physical activity and sedentary behaviors with questionnaires in surveillance systems ... 28

2.1 Classification of self-report tools of sedentary behaviors ... 28

2.2 Type of questionnaires ... 30

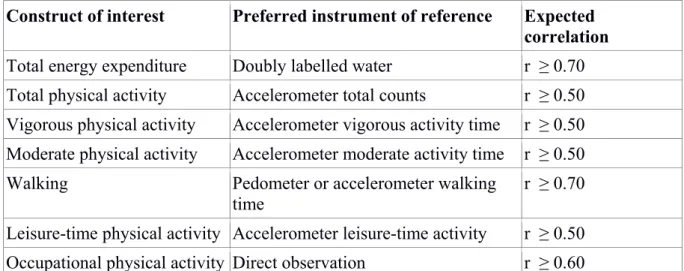

2.3 Measurement properties of questionnaires ... 32

2.3.1 Validity ... 32

2.3.2 Reliability ... 34

2.3.3 Responsiveness ... 35

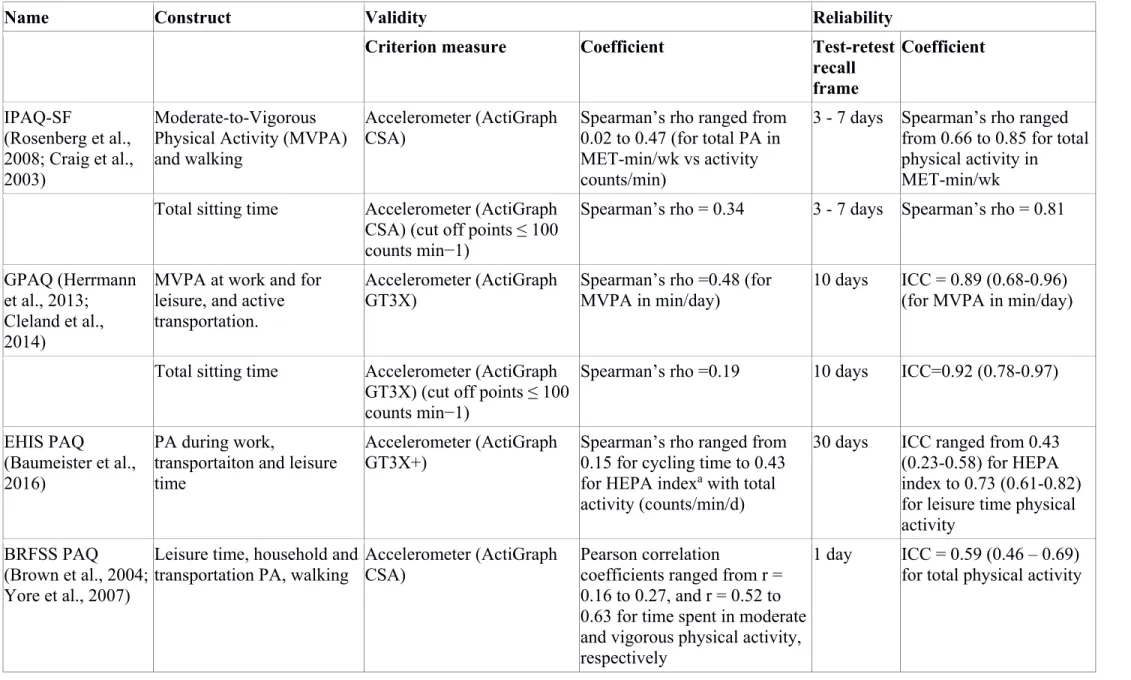

2.4 Validity and reliability studies of the GPAQ ... 38

2.5 Summary ... 39

3 Public health surveillance ... 40

3.1 Definition and concepts ... 40

3.2 Objectives of public health surveillance ... 41

3.3 Types of surveillance systems ... 42

3.4 Historical overview of WHO non-communicable diseases surveillance ... 43

3.5 Surveillance of physical activity and sedentary behaviors ... 46

3.5.1 Worldwide surveillance ... 46

3.5.2 National surveillance ... 50

3.6 Summary ... Chapter 3. Personal contribution ... 57

Study 1. Surveillance of physical activity and sedentary behaviors: case-study using French surveillance data ... 58

Study 2. Results from the first French Report Card on physical activity for children and adolescents (2016) ... 86

Study 3. Reliability and validity of the French version of the global physical activity questionnaire ... 100

Study 4. Content comparison of sedentary behaviors questionnaires: a systematic review 108 Chapter 4. General discussion ... 157

1 Study 1. Surveillance of physical activity and sedentary behaviors: case-study using

French surveillance data ... 157

1.1 Main results ... 157

1.2 Discussion ... 158

1.3 Strengths and limitations ... 160

2 Study 2. Results from the first French Report Card on physical activity for children and adolescents (2016) ... 160

2.1 Main results ... 160

2.2 Discussion ... 161

2.3 Strengths and limitations ... 161

3 Study 3. Reliability and validity of the French version of the global physical activity questionnaire ... 162

3.1 Main results ... 162

3.2 Discussion ... 163

3.3 Strengths and limitations ... 164

4 Study 4. Content comparison of sedentary behaviors questionnaires: a systematic review ... 165

4.1 Main results ... 165

4.2 Discussion ... 166

4.3 Strengths and limitations ... 167

5 Perspectives ... 168

5.1 Public health perspectives ... 168

5.2 Research perspectives ... 171

6 Conclusion ... 173

References ... 175

List of tables

Table 1. Physical activity quantitative components………..………15 Table 2. Classification of aerobic exercise intensity……….17 Table 3. Quality assessment of questionnaire………...34 Table 4. Overview of the measurement qualities of a sample of questionnaire used in physical activity and sedentary behaviors surveillance systems……….36 Table 5. Illustration of the conceptual framework underlying the WHO STEPwise approach (from WHO, 2005)………45

List of figures

Figure 1. ActiGraph representation of physical activity………...19

Figure 2. ActiGraph representation of physical activity………...20

Figure 3. Illustration of different patterns of breaks in sedentary time, based on accelerometer data from 2 adults with identical total time spent being sedentary………...23

Figure 4. Conceptual model for defining and assessing physical activity and energy expenditure ……….. 24

Figure 5. Conceptual framework for physical activity and sedentary behaviors ……….26

Figure 6. Taxonomy level one facets and coding labels ………..27

Figure 7. Taxonomy of Self-reported Sedentary Behavior Tools……….30

Figure 8. Approaches to measuring physical and sedentary behaviors by report and devices……….172

Publications

Peer-review publications

Published articles

Rivière, F., Widad, F. Z., Speyer, E., Erpelding, M. L., Escalon, H., & Vuillemin, A. (2016).

Reliability and validity of the French version of the global physical activity questionnaire. Journal of Sport and Health Science.

Aucouturier, J., Ganière, C., Aubert, S., Riviere, F., Praznoczy, C., Vuillemin, A., Tremblay, M. S., Duclos, M., & Thivel, D. (2017). Results From the First French Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Adolescents (2016). Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 1-14.

Submitted articles

Rivière, F., Aubert, S., Yacoubou Omorou, A., Ainsworth, B.E., & Vuillemin, A. Content

comparison of sedentary behavior questionnaires: a systematic review.

Rivière, F., Escalon, H., Duché, P., Drouillet-Pinard, P., & Vuillemin, A. Surveillance of

physical activity and sedentary behaviors: case-study using French surveillance data.

Non peer-review publications

Book chapters

Ainsworth, B. E., Pregonero, A. F., & Rivière, F. (2017). Assessing sedentary behavior using

questionnaires. In W. Zhu & N. Owen (Eds.), Sedentary behavior and health concepts, assessments, and interventions (pp.165-174, 386-388). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Ainsworth, B. E., Rivière, F., & Florez Pregonero, A. Measurement of sedentary behavior in

population studies. In Sedentary Behavior Epidemiology. Upcoming in: Springer.

Report

ONAPS (2017). 2016 – Activité physique et sédentarité de l’enfant et adolescent – Premier état des lieux en France. Available at : http://www.onaps.fr/data/documents/RC2016.pdf

Communications

Oral communications

Rivière, F., & Vuillemin, A. (2016). Analysis of the surveillance system of physical activity

and sedentary behavior in France. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Physical Activity and Public Health. Bangkok, Thailand.

Ainsworth, B. E., & Rivière F. (2015). Assessing sedentary behavior using questionnaires. In:

Proceedings of the Sedentary Behavior and Health Conference. Urbana Champaign, Illinois, USA.

Rivière, F., Aubert, S., Yacoubou Omorou, A, Ainsworth, B. E., & Vuillemin, A. (2015).

Content comparison of sedentary behavior questionnaires: a systematic review. In: Proceedings of the HEPA Europe Conference. Instanbul, Turkey.

Written communications

Rivière, F., & Vuillemin, A. (2016). Analysis of the surveillance system of physical activity

and sedentary behavior in France. In: Proceedings of the HEPA Europe Conference. Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Rivière, F., Aubert, S., Omorou, A., Ainsworth, B. E., Vuillemin, A. (2015). Content

comparison of sedentary behavior questionnaires: a systematic review. In: Proceedings of the Sedentary Behavior and Health Conference. Urbana Champaign, Illinois, USA.

Abbreviations

ACSM: American College of Sports Medicine AHS: Australian Health Survey

Anses: French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety BRFSS: United States Behavioral Risk Factor Survey System

CCHS: Canadian Community Health Survey CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CHMS: Canadian Health Measures Survey EMA: Ecological Momentary Assessment

ENNS: French National and Health Nutrition Study

Eprus: French Preparedness and Sanitary Emergency Response Establishment GoPA!: Global Observatory for Physical Activity

GPAQ: Global Physical Activity Questionnaire HCSP: French High Committee on Public Health HIS: Belgium Health Interview Survey

HRmax: Maximal Heart Rate

Inpes: French National Institue for Prevention and Health Education InVS: French Institute for Public Health Surveillance

IPAQ: International Physical Activity Questionnaire

ISPAH: International Society for Physical Activity and Health LOLF: French Organic Law on the Finances Laws

METs: Metabolic Equivalent of Task – multiples of resting energy expenditure NHANES: United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey NCDs: Non-Communicable Diseases

PAM: Canadian Physical Activity Monitoring

PNNS: French National Nutrition and Health Program RPAQ: Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire RPE: Ratings of Perceived Exertion

SAMSS: South Australian Monitoring and Surveillance System SBRN: Sedentary Behavior Research Network

SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals VO2max: Maximal Oxygen Consumption WHO: World Health Organization

Chapter 1

Introduction

Context

Health impacts of physical activity have been increasingly studied since the 1950s and are now well-established (Morris et al., 1953a; Erlichman et al., 2002; Powell et al., 2011; Garber et al., 2011; Ekelund et al., 2016; Lear et al., 2017). Physical activity is associated with a number of health outcomes, including reduced risks of breast cancer, colon cancer, coronary heart disease, depression, fractures, osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes, and improvement in cognitive function, physical function and weight management (Powell et al., 2011; Garber et al., 2011). Despite these health benefits, nearly one third of the world population does not engage in physical activity at recommended levels (Hallal et al., 2012). The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified the lack of physical activity as the fourth global risk factor for mortality (WHO, 2009), and it is estimated to be responsible for 6 to 9 percent of worldwide premature deaths (WHO, 2009; Lee et al., 2012). As a consequence, the economic burden attributable to the lack of physical activity is estimated to be at least 67.5 billion international dollars worldwide, and 15.5 billion international dollars in Europe (Ding et al., 2016).

In 2010, WHO published global recommendations for physical activity for health (WHO, 2010). According to these recommendations, adults aged 18-64 years should engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week, or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity physical activity, or an equivalent combination. This activity should occur in bouts of at least 10 minutes or longer. In addition, muscle-strengthening activities should be done at least 2 times per week. In France, the French Ministry of Health, as part of the National Nutrition and Health Program (PNNS), recommended that adults engage in at least 30 minutes of brisk walking daily, or an equivalent amount of physical activity (PNNS 2011-2016, PNNS 2006-2010, PNNS 2001-2005), and for youth should engage in at least 60 minutes of brisk walking daily, or an equivalent amount of PA (PNNS 2011-2016). Recently, the French Agency

for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (Anses), at the request of the Directorate General for Health (French Ministry of Health), has published updated recommendations for physical activity in toddlers (0-5 years), children (6-11 years), adolescents (12-17 years), adults (18-65 years) and elderly (65 and above) (Anses, 2016).

The term sedentary behaviors covers a whole range of different activities spent sitting, including watching TV, using a computer, driving a car, working at a desk and eating breakfast. Based on international data, worldwide siting time was estimated to be five hours per day (Bauman et al., 2011). Sedentary behaviors are recognized as a health risk associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Jeffery and French, 1998; Van Der Ploeg et al., 2012; Biswas et al., 2015). A systematic literature review and meta-analysis published by Biswas and colleagues reported positive associations between time spent in sedentary behaviors and type 2 diabetes incidence, cancer incidence and mortality, cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality, and all-cause mortality (Biswas et al., 2015). Individuals who accumulate low levels of physical activity and high sedentary time are at highest risk for the associated health risks of these behaviors (Chau et al., 2013; Biswas et al., 2015; Ekelund et al., 2016).

WHO has not made recommendations for the minimal time spent in sedentary behaviors. This is attributable to the fact that epidemiology of sedentary behaviors is a new field of research, thus at the time when WHO published its recommendations for physical activity, little was known on the relationship between sedentary behaviors and health-related outcomes. Since then many countries have published recommendations for sedentary behaviors (Tremblay et al., 2011a; Parrish et al., 2013; Kahlmeier et al., 2015), including France (Anses, 2016).

Being a major determinant of health and well-being, and in regard to the burden of mortality and morbidity associated with insufficient physical activity levels and too much sedentary behaviors, public health systems have integrated surveillance of physical activity and sedentary behaviors (WHO, 2005; Fulton et al., 2016; Craig et al., 2017). Public health surveillance is the foundation of public health systems. Surveillance activities are used to estimate the health status and health determinants of populations, evaluate existing interventions, and plan for future interventions (Macera and Pratt, 2000; German et al., 2001). Public health surveillance is an indispensable process for decision-makers in planning strategies and actions by providing timely, useful evidence. However, the implementation of reliable surveillance systems is complicated. To measure physical activity and sedentary behaviors, one of the main challenges is to rely on accurate measurement of physical activity and sedentary behaviors. Accurate and reliable measures of these behaviors are important for surveillance systems to assess the

prevalence of physical activity levels and sedentary lifestyles, to study the relationships between physical and sedentary behaviors and health outcomes, to characterize the patterns of the population and to plan and evaluate health promotion interventions.

Two main methods of measurement are used to survey these behaviors: self-report questionnaires and objective methods, including pedometers and accelerometers. Questionnaires are cost-effective, readily accessible to the majority of the population, have a relatively low participant burden, and can be used to identify types of behaviors in the context in which the behaviors occur. Therefore, population-based studies have mostly relied on self-report questionnaires (Sjöström et al., 2006; Beck et al., 2008; Fulton et al., 2016; Craig et al., 2017). Questionnaires are prone to both over and underestimating physical activity and sedentary time (Prince et al., 2008). Alternatively, objective methods might improve quantification of these behaviors. Accelerometers provide a measurement of the frequency and time spent in body movement by intensity used to discriminate between physical activity and sedentary behaviors (Hills et al., 2014). Accelerometers have been used in national (Troiano et al., 2008; Hagströmer et al., 2010; Colley et al., 2011), European (Konstabel et al., 2014; Loyen et al., 2016) and international surveys (Van Dyck et al., 2005) to measure physical

activity and sedentary behaviors. Accelerometers also have their limitations. In particular, they

do not provide information on the type or context of the behaviors and they measure sedentary behaviors poorly. Ideally national surveys should rely on both self-report and objective methods to provide a complete picture of the population physical activity and sedentary behaviors (Troiano et al., 2012).

Research aims and questions

Physical activity and sedentary behaviors are major health determinants and are being surveyed worldwide (WHO, 2005; Fulton et al., 2016; Bel-Serrat et al., 2017; Craig et al., 2017). In some countries, such as the United States and Canada (Fulton et al., 2016; Craig et al., 2017), the implementation of surveillance studies measuring physical activity and sedentary behaviors is well defined. In France, physical activity and sedentary behaviors surveillance is still in an early stage, and needs improvement. There is no consensus about what is the optimal survey and how best to measure physical activity and sedentary behaviors in surveillance setting. In France, questionnaires are used primarily, but there is a lack of consistency in the choice of the

questionnaire. Therefore, this thesis aimed to add to the current knowledge by answering three research questions:

What is the current state of physical activity and sedentary behaviors surveillance in

France?

What are the psychometric properties of the French version of the Global Physical

Activity Questionnaire?

What do sedentary behaviors questionnaires measure?

Research studies

To answer these questions, this thesis includes four studies. Two studies have been published in international reviewed journals, and two have been submitted to international peer-reviewed journals. The four studies focus on one of the two research axes as presented below.

Axis 1. Surveillance of physical activity and sedentary behaviors

Study 1. Rivière, F., Escalon, H., Duché, P., Drouillet-Pinard, P., & Vuillemin, A.

Surveillance of physical activity and sedentary behaviors: case-study using French surveillance data.

Study 2. Aucouturier, J., Ganière, C., Aubert, S., Riviere, F., Praznoczy, C., Vuillemin, A.,

Tremblay, M. S., Duclos, M., & Thivel, D. (2017). Results From the First French Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Adolescents (2016). Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 1-14.

Axis 2. Measurement of physical activity and sedentary behaviors

Study 3. Rivière, F., Widad, F. Z., Speyer, E., Erpelding, M. L., Escalon, H., & Vuillemin,

A. (2016). Reliability and validity of the French version of the global physical activity questionnaire. Journal of Sport and Health Science.

Study 4. Rivière, F., Aubert, S., Yacoubou Omorou, A., Ainsworth, B.E., & Vuillemin, A.

Chapter one provides an introduction to the thesis.

Chapter two provides an overview of the complex and multidimensional nature of physical activity and sedentary behaviors, as well as the complexity of measuring and surveying these behaviors. Chapter two has three sections. The first section provides information regarding definitions and frameworks of physical activity and sedentary behaviors. It also describes the multidimensional nature of physical activity and sedentary behaviors. The second section provides an overview of measurement methods used in large-scale physical activity and sedentary behaviors studies. The last section discusses worldwide and French surveillance of physical activity and sedentary behaviors.

Chapter three presents the research manuscripts included in this thesis. The first study analyzes and discusses the present situation of French national surveillance studies, including measurement of physical activity and sedentary behaviors. The second study presents the results from the first French report card on physical activity for children and adolescents. The third study discusses the validity and reliability properties of the French version of the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire. The fourth study examines the content of questionnaires measuring sedentary behaviors.

Chapter four presents a general discussion of the four studies completed for the thesis. In this context, the studies are summarized and discussed in a broader perspective. In addition, the strengths and limitations of the research included in this thesis are discussed with recommendations made for future research and practice.

Chapter 2

Literature Review

1 Physical activity and sedentary behaviors: concepts and

definitions

1.1 Definitions of physical activity

Prior to 1985, a consensual definition of physical activity did not exist (Laporte et al., 1984; Stephens, 1987). In 1985, Caspersen and colleagues defined physical activity as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure” (Caspersen et al., 1985). This definition has received wide acceptance among the scientific community, as evidenced by the number of times it has been cited (more than 6,000 citations). In 2012, Pettee-Gabriel et al. introduced a framework for physical activity and proposed to define physical activity as “the behavior that involves human movement, resulting in physiological attributes including increased energy expenditure and improved physical fitness” (Pettee-Gabriel et al., 2012). According to Pettee-Gabriel, physical activity includes all kinds of activity that could occur in different contexts including occupational, transport, domestic and leisure time, which consists of exercise, sport and unstructured recreation (Pettee-Gabriel et al., 2012; Khan et al., 2012). These two definitions appear to be used most frequently by researchers who study physical activity.

1.2 Terms used in the measurement of physical activity

Physical activity characteristics in terms of mode, frequency, intensity, and duration are usually used to quantify physical activity. These terms are defined in Table 1 and are discussed in the following section 1.2.1, to 1.2.4.

Table 1. Physical activity quantitative components (definitions from Strath et al., 2013).

Mode Specific activity performed (e.g. walking, gardening, cycling). Mode can also be defined in the context of physiological and biomechanical demands/types (e.g. aerobic versus anaerobic activity, resistance or strength training).

Frequency Number of sessions per day or per week. In the context of health-promoting

physical activity, frequency is often qualified as number of sessions (bouts) ≥10 min in duration/length.

Duration Time (minutes or hours) of the activity bout during a specified time frame (e.g. day, week, year, past month).

Intensity Rate of energy expenditure. Intensity is an indicator of the metabolic demand of an activity. It can be objectively quantified with physiological measures (e.g. oxygen consumption, heart rate), subjectively assessed by perceptual characteristics (e.g. rating of perceived exertion, walk-and-talk test), or quantified by bodily movement (e.g. stepping rate, 3-dimensional body accelerations).

1.2.1 Intensity

Intensity is an important determinant of the physiological responses to physical activity. Time spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity may be one of the most common measure of physical activity. Either moderate- or vigorous- intensity physical activity, or a combination of both, can be undertaken to meet the WHO physical activity guidelines (WHO, 2010). Intensity can be expressed in absolute or relative values (see Table 3). Physical activity intensities are categorized into five levels that include cut-points for relative and absolute intensity levels. Absolute intensity refers to the amount of work required to perform a specific activity regardless of an individual’s physical attributes. Absolute intensity is often expressed in multiples of resting energy expenditure (METs), with 1 MET=3.5 ml/kg/min. Physical activity intensity varies along a continuum from sedentary (≤1.5 METs) to high intensity activity (≥ 8.8 METs). As an example, absolute intensity can be as low as 0.95 METs for sleeping and as high as 23.0 METs for running at 22.5 kilometers per hour (Ainsworth et al., 2011). For aerobic activities, intensity may be expressed in physiological values as heart rate (pulses/minutes) and oxygen

consumption (VO2 in l/min), or as a rate (running speed per hour). As an example, running at

22.5 kilometers per hour corresponds to an intensity of 23.0 METs and requires an oxygen consumption of 80 ml/kg/min (23.0 METs * 3.5 ml/min/kg = 80) to be performed. For strength

exercises, intensity can be expressed as the amount of weight lifted (for example a maximal weight of 100 kilograms lifted during squat).

Relative intensity refers to the amount of work required to perform a specific activity adjusted for an individual physiological capacity. Therefore, it can be expressed using the same indicators as for absolute intensity, but adjusted for the percent of maximal capacity of the individual. In this way relative intensity may be expressed as percentages of maximal heart rate, maximal oxygen consumption, maximum rate of energy expenditure, maximum aerobic speed or maximum weight lifted. In addition, relative intensity can be expressed as perceived exertion. Various perceived exertion scales have been developed, but the most popular is the Borg RPE scale (Borg, 1998). The Borg RPE scale is a scale for ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) based

on the physical sensations a person experiences during physical activity, including

breathlessness, increased heart rate and fatigue. The Borg RPE scale ranges from 6 to 20, where 6 means “No exertion at all” and 20 means “Maximal exertion”. Perceived exertion as measured using Borg RPE scale has been shown to be associated with physiological measures such as percent maximal oxygen uptake and percent maximal heart rate (Chen et al., 2002). While doing physical activity, RPE can be used to determine perceived physical activity intensity by choosing the number that best describes the level of exertion during the physical activity. For example, 13 is defined as a level of exertion somewhat hard, and corresponds to a moderate-intensity physical activity.

Table 2. Classification of aerobic exercise intensity (adapted from ACSM, 2011 and Norton et al., 2010).

Intensity category Relative intensity Absolute intensity

Sedentary < 40% HRmax <20% VO2max RPE < 8 ≤1.5 METs Light 40 – 63% HRmax 20 – 45% VO2max RPE 9 - 11 1.6 – 2.9 METs Moderate 64 – 76% HRmax 46 – 63% VO2max RPE 12-13 3.0 – 5.9 METs Vigorous 77 – 95% HRmax 64 – 90% VO2max RPE 14 - 17 6.0 – 8.7 METs High ≥ 96% HRmax ≥ 91% VO2ma RPE ≥18 ≥ 8.8 METs

HRmax: maximal heart rate ; VO2max: maximal oxygen consumption; METs: multiples of

resting energy expenditure; RPE: rating of perceived exertion.

1.2.2 Duration

An aspect of duration is to describe the length of time an individual engages in physical activity over a specified period. For example, WHO recommends children and adolescents aged 5-17 years engage in 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity every day of the week. Adults aged 18 and older should perform 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity throughout the week, or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous intensity physical activity (WHO, 2010). A second aspect of duration is to describe the time spent in continuous physical activity at a certain intensity, or engaged in a given activity. For example, an individual could engage in a continuous 30-minute brisk walk, or accumulate the same duration of exercise in bouts (e.g. 2 brisk walks of 15 minutes). WHO recommends to accumulate physical activity in bouts lasting at least 10 minutes (WHO, 2010).

1.2.3 Frequency

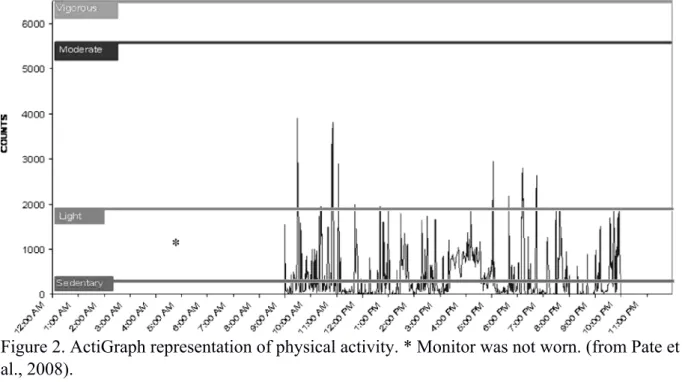

Frequency refers to how often an individual engages in physical activity in terms of the number of times a week, month, or year. For example, WHO’s physical activity guidelines advise for adults aged 18 years and older to perform muscle-strengthening activities 2 or more days a week (WHO, 2010). The 1995 CDC-ACSM (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – American College of Sports Medicine) physical activity guidelines recommended adults engage in moderate-intensity physical activity 5 days per week (Pate et al., 1995). The 1978 ACSM guidelines recommended adults engage in vigorous exercise 3-5 days per week (ACSM, 1978). Another important aspect of frequency is the number of times an individual engages in bouts of physical activity. Individuals can perform short bouts of activity throughout the day or engage in continuous physical activity. For example, in Figure 1, the participant engaged in one continuous bout of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity, while in Figure 2 the participant engaged in many short bouts of moderate-intensity physical activity.

Figure 1. ActiGraph representation of physical activity. * Monitor was not worn. (from Pate et al., 2008).

Figure 2. ActiGraph representation of physical activity. * Monitor was not worn. (from Pate et al., 2008).

1.2.4 Mode

The mode refers to the specific activity performed (e.g. walking, running) or to the type of physical activity (e.g. aerobic activity, muscle-strengthening activity). Recommendations for physical activity include different types of physical activity, such as aerobic physical activity, muscle-strengthening activities, flexibility and balance exercises (Haskell et al., 2007; WHO, 2010; Anses, 2016). For example, Anses recommends adults engage in 30 minutes of physical activity of moderate-to-vigorous intensity at least 5 days a week to develop cardiorespiratory capacity. Specific activities that increase cardiorespiratory capacity include running, swimming and cycling. In addition, Anses recommends adults perform muscle strengthening activities once or twice a week and flexibility exercises 2 or 3 times a week (Anses, 2016). Strengthening activities refer to weight lifting activities, such as pressing a weight upwards from a supine position and carrying shopping. Stretching activities include yoga and tai chi type activities.

1.3 Definition of sedentary behaviors

As the term sedentary behaviors has gained in popularity over the last two decades, different definitions have emerged. Historically, the term sedentary was used to describe a person with low physical activity levels (Paffenbarger et al., 1986, Lowry et al., 2002) and it was used interchangeably with physical inactivity (Dietz, 1996). In 2007, the term sedentary behaviors was used to describe a distinct and specific behavior, primarily sitting, including activities such as watching TV or using a computer (Hamilton et al., 2007). In 2008, Pate et al. more clearly defined sedentary behaviors based on the activity energy expenditure, and made the

differentiation between sedentary behaviors (1.0-1.5 METs), and light physical activities (1.6-2.9 METs) (Pate et al., 2008). According to Pate et al. “sedentary behavior refers to activities that do not increase energy expenditure substantially above the resting level and includes activities such as sleeping, sitting, lying down, and watching television, and other forms of screen-based entertainment” (Pate et al., 2008, p. 174). In 2010, Owen et al. made explicit that sedentary behaviors involve a specific posture (sitting) combined with a low level of energy expenditure (1.0-1.5 METs) (Owen et al., 2010). Furthermore, Owen et al. highlighted the fact that sedentary behaviors could occur in different contexts, including during commuting, in the workplace and the domestic environments, and during leisure time (Owen et al., 2010). In 2012, the Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) defined sedentary behaviors as “as any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 METs while in a sitting, or reclining posture” (SBRN, 2012), thus excluding sleeping as a sedentary behavior (Pate et al., 2008). The SBRN definition has been largely used since, and seems to have received broad acceptance among the academic community. In 2017, the SBRN complemented their definition by including the posture of lying down. The SBRN now defines sedentary behaviors as “any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 METs while in a sitting, reclining, or lying posture” (Tremblay et al., 2017).

1.4 Terms used in the measurement of sedentary behaviors

Sedentary behaviors can be described using the SITT formula (Tremblay et al., 2010), corresponding to: Sedentary behaviors frequency (operationalized as number of bouts of a certain duration), Interruptions or breaks in sedentary time (such as standing up or walking), Time (operationalized as the duration of sedentary behaviors), and Type (mode of sedentary behaviors, such as watching TV or driving a car).

1.4.1 Sedentary time

Sedentary time, expressed in seconds, minutes or hours, can refer to the total time spent in sedentary behaviors, or to the time spent in each sedentary activity. For example, in France it is recommended for adults to reduce the total time daily spent in a sitting position, as much as possible, and to limit each sedentary activity, to not exceed 90 to 120 minutes continuously (Anses, 2016). Total time spent in sedentary behaviors can be measured directly or calculated by summing time spent in specific sedentary activities.

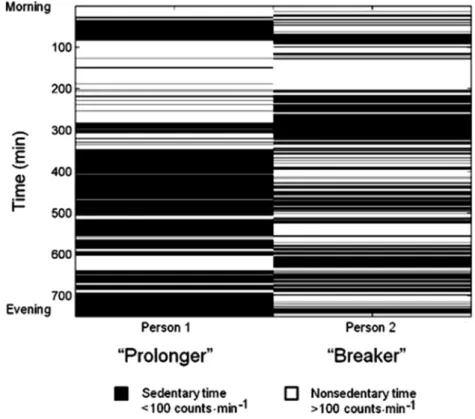

Interruption in sedentary time is defined as a non-sedentary period in between two sedentary bouts and is often referred to as break in sedentary time (Altenburg and Chinapaw, 2015). Figure 3 illustrates how two individuals can accumulate the same volume of total sedentary time with two different patterns of breaks in sedentary time. Sedentary time can be accumulated in extended continuous bouts, or with frequent interruptions and in short bouts (Dunstan et al., 2010). One difficulty in measuring breaks in sedentary time is the lack of an operational definition. In their study, Healy et al. (2008) defined a break as a 1-minute interruption in sedentary time with accelerometer counts higher than 100 counts per minute (Healy et al., 2008). This definition seems to have received acceptance among the academic community as it has been widely used (Cooper et al., 2012; Saunders et al., 2013; Colley et al., 2013). However, others have made different choices. Carson et al. have operationalized breaks as interruptions of more than 5 seconds and Verloigne et al. have defined breaks as interruptions of 15 seconds (Carson et al., 2014; Verloigne et al., 2017).

Figure 3. Illustration of different patterns of breaks in sedentary time, based on accelerometer data from 2 adults with identical total time spent being sedentary (from Dunstan et al., 2010).

Frequency of sedentary bouts refers to the number of sedentary bouts of a certain duration. To date, there is no consensus on the minimum period a sedentary bout should last. In a discussion of sedentary time, Altenburg and Chinapaw observed that many different operational definitions of sedentary bouts were used in research (Altenburg and Chinapaw, 2015) including at least 30 min with ≥80% of time below the sedentary cut-point of 100 counts/minute (Carson et Janssen, 2011) and at least 20 min with ≥80% of time below the sedentary cut-point of 100 counts/minute (Colley et al., 2013). Others have defined a sedentary bout as a continuous period of sedentary time below the sedentary cut-point of 100 counts/minutes (Saunders et al., 2013; Carson et al., 2014) or 25 counts per 15 seconds (Verloigne et al., 2017). Because it is unknown how long a sedentary bout is related to negative health effects, Altenburg and Chinapaw recommended a sedentary bout be defined as a minimum period of uninterrupted sedentary time not allowing any “tolerance time” (defined as non-sedentary time) (Altenburg and Chinapaw, 2015).

1.4.4 Mode of sedentary behaviors

Type of sedentary behaviors refers to the mode of sedentary behaviors, such as watching TV, using a computer or driving a car. Often, time spent in TV viewing is used as a proxy measure of sedentary behaviors duration (Dunstan et al., 2005). Time-use surveys have reported that, aside from sleeping, watching TV was the behavior that occupies the most time in the domestic setting (Office for National Statistics, 2005; Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006; United States Departement Labor, 2007). However, it has been suggested that TV viewing may not always be a robust marker of a sedentary lifestyle (Sugiyama et al., 2008, Owen et al., 2010). Therefore, all types of sedentary behaviors need to be measured.

1.5 Conceptual models of physical activity and sedentary behaviors

This section will present three conceptual models used in the field of physical and sedentary behaviors epidemiology that can be used to guide research. The work of LaMonte and Ainsworth (2001), Pettee-Gabriel and Morrow. (2012), and Chastin et al. (2013) will be presented following a chronological order. In addition, an ongoing project (ALPHABET project) will be presented.

1.5.1 Measurement model for physical activity and energy expenditure (LaMonte and Ainsworth, 2001)

In 2001, LaMonte and Ainsworth proposed a framework for measuring physical activity and energy expenditure, collectively referred to as human movement (Figure 4) (LaMonte and Ainsworth, 2001). This framework made the distinction between physical activity, as a behavior, and energy expenditure, as the energy cost of the behavior. The framework provides examples of measurement methods using direct and indirect measures of physical activity and energy expenditure. For physical activity, direct measures include motion sensors, direct observation and global positioning system. Indirect measures include physical activity records, 24-hour recalls and questionnaires. For energy expenditure, direct measures include calorimetry and doubly labeled water. Indirect measures include oxygen uptake, heart rate, body temperature and ventilation. For each measurement method, it is possible to extrapolate each metric to energy expenditure for use in analysis of energy expenditure and health outcomes.

Figure 4. Conceptual model for defining and assessing physical activity and energy expendituree (from LaMonte and Ainsworth, 2001).

1.5.2 Model for the physical activity domains (Pettee-Gabriel and Morrow, 2010)

In 2010, Pettee-Gabriel and Morrow, proposed a framework for human movement, representing physical activity and sedentary behaviors as two components of human movement (see Figure 5) (Pettee-Gabriel and Morrow, 2010). The framework makes the distinction between the behaviors (physical activity and sedentary behaviors) and the physiological results or consequences of movement (energy expenditure and physical fitness). The framework identifies four domains where physical activity can take place (leisure, occupation, household, and transport), and classifies sedentary behaviors as non-discretionary or discretionary. Examples of discretionary and non-discretionary sedentary behaviors are presented. Discretionary sedentary behaviors include sitting, media use, non-occupational, school and computer use. Non-discretionary sedentary behaviors include sleeping, occupation, school, sitting while driving and sitting while riding.

1.5.3 Taxonomy of sedentary behaviors

In 2013, Chastin and colleagues developed a taxonomy (naming and cataloging system) of sedentary behaviors (Chastin et al., 2013). The taxonomy of sedentary behaviors is the result of the first round of an open science project (collaborative work opened to everyone) called “SIT” (Sedentary behaviors International Taxonomy project). Led by Chastin et al. this formal consensus process offered a comprehensive frame of reference for sedentary behaviors developed through a Delphi method involving international experts. The Delphi method is a collaborative forecasting technique that relies on a panel of experts. Delphi method combines independent analysis with maximum use of feedback, for building consensus among experts who interact anonymously during 2 or more rounds. At each round, experts answer questions and provide input on the subject of interest, until some degree of mutual agreement is reached among the experts. The taxonomy includes 9 complementary facets (categories) (see Figure 6) characterizing the purpose (why), the environment (where), the social context (with whom), the type or modality (what), associated behaviours (what else), when the behaviour take place (when), the mental and functional states of sedentary individual (state), the posture, and the measurement and quantification issues (Chastin et al., 2013). The taxonomy provides a standardized classification of sedentary behaviors, and should help in harmonizing the collection, organization and retrieval of relevant data and information on sedentary behaviors.

1.5.4 ALPHABET project

ALPHABET is described as an open science project aiming to develop a common taxonomy for classification, harmonization and storage of objective tracking sensor data of human physical behavior in daily life, through an international consensus process using the Delphi Method. It aims to reach international consensus on an overarching definition for the study of how activities, physical actions and movements as part of human daily behavior impacts health and well-being; and on an integrated classification system, data model and nomenclature. A brief description is available online (AlPHABET: Development of A Physical Behaviour Taxonomy with an international open consensus. Retrieved October 14, 2017 from https://osf.io/2wuv9/).

1.6 Summary

Physical activity and sedentary behaviors are human movement behaviors, and are commonly defined based on their energy expenditure attribute. To avoid confusion, definitions and conceptual models have been developed. Sedentary behavior is defined as “as any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 METs while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture” (Tremblay et al., 2017). Physical activity has been defined as “the behavior that involves human movement, resulting in physiological attributes including increased energy expenditure and improved physical fitness” (Pettee-Gabriel and Morrow 2012). In addition, conceptual models emphasize the importance to make the distinction between the behaviors, that could occur in different settings, and the physiological consequences of the behaviors (LaMonte and Ainsworth, 2001; Pettee-Gabriel and Morrow, 2010). Depending on the construct of interest, different measuring tools must be used (LaMonte and Ainsworth, 2001).