Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Echahid Hamma Lakhdar University, Eloued

Faculty of Arts and Languages Department of Arts and English Language

Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Master Degree in Literature and Civilization

Submitted by: Supervised by: Touraya KINA Mr. Kouider YOUCEF Siham GHEMIMA

Rima DJERRAYA

Board of Examiners

Chairman/President: Miss. KHELEF Embarka

University of El-Oued

Supervisor: Mr. YOUCEF Kouider

University of El-Oued

Examiner: Dr. ANAD Ahmed

University of El-Oued

Academic Year: 2019/2020

Women's Status in Britain

during the First World War꞉

I

Dedication

We dedicate this work to our beloved parents, brothers and sisters for their

patience with us and valuable encouragement because without their support, the

work wouldn’t be done.

To our relatives and all people who know us.

To our dear friends.

II

Acknowledgements

All our thanks are firstly given to Allah the almighty for his blessings. Our special gratitude and appreciation is owed to our supervisor Mr. KOUIDER Youcef for his help, guidance, advice, suggestions and his patience with us to achieve our aim from this work.

We would like also to thank Mr. Zelouma Ahmed for his help and support.

Thanks to all our teachers in English department in Haman Lakhdar University of El-Oued.

III

Abstract

The First World War (1914-1918) had great effect on men as well as on women; and this was manifest in many different aspects such as human life and property, political, social and economic fields. The present dissertation is concerned with the study of the impact of the First World War on British women. When the war began, women’s lives had socially, politically and economically changed because of the new circumstances as the British women filled the empty jobs left behind by males and they participated in the war effort. Given the fact that the Great War had affected women's lives in all aspects, our research is aimed at showing the main changes which had a considerable impact on women’s status. Some people saw that the war was a sign of liberation for many women because it brought to them some new rights they missed before 1914. However, others thought that this status did not serve women and did not represent their freedom because it was only for the war duration as the British women were needed to fill the gaps of men in many different fields during the war. Thus, to conduct our research, we opted for a qualitative approach through the collection of relevant data. Furthermore, we adopted the descriptive analytical method in order to trace some events during that period and to verify the hypothesis. The conclusion we came to in our research shows that World War One was not an opportunity for women in Britain to achieve liberation; on the contrary they felt compelled to meet more obligations, i.e. World War One was mostly obligation rather than liberation. This study might pave the way to further researches and researchers interested in studying the status of women during World War One.

IV

List of Abbreviations

FA꞉ Football Association

FANY: First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

FDT: Field Device Tool

LSWS: London Society for Women’s Suffrage

MP : Member of Parliament

NU: National Union

NUWSS: National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies

PSF: People’s Suffrage Federation

RAF: Royal Air Force

UK: United Kingdom

VAD: Voluntary Aid Detachment

WAAC: Women’s Auxiliary Army Corp

WCG: Women's Co-operative Guild

WFL: Women’s Freedom League

WLA: Women’s Land Army

V WRNS: Women’s Royal Naval Service

WSPU: Women’s Social and Political Union

VI

List of Tables

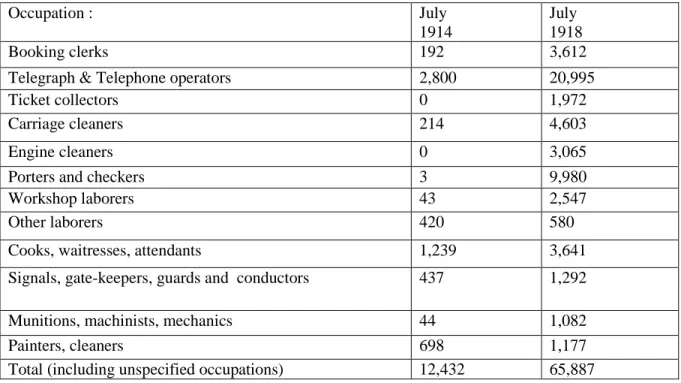

Table 1: Employed females in the UK during the First World War………...54

Table 2: Changes in female employment within industry during the war………..55

Table 3: Changes in female employment within transport during the war………...56

VII

List of Figures

Figure 1: The war of munitions. A woman checking shell primers in1917……….30 Figure 2: Members of the Women’s Land Army feeding pigs and calves………..34

VIII

Table of Contents

Dedication ... I Acknowledgements ... II Abstract ... III List of Abbreviations ... IV List of Tables ... VIList of Figures ... VII

Table of Contents ... VIII

General Introduction ... 1

1. Background of the Study ... 1

2. Statement of the Problem ... 1

3. Aim of the Study ... 2

4. The Significance of the Research ... 2

5. Research Questions ... 2

6. Research Hypotheses... 2

7. Research Methodology ... 3

8. Structureof the Dissertation ... 3

IX

Introduction ... 5

1.The Social Status of Women in Britain before the First World War ... 6

1.1. Women's Lives during the Celtic Period ... 6

1.2.Women's Marriage without Respecting the Family's Relation for Keeping the Family's Property (The Anglo -Saxon) ... 7

1.3. In the Middle Ages: Women under the Authority of Men ... 7

1.3.1. Women and Marriage꞉ Women's Marriage as a means for the Family's Wealth ... 7

1.3.2. The Life of Married Women ... 8

1.4. Women's Lives during the Tudor Period (1485-1603) ... 9

1.5. Women between the Authority of Husbands and Parents in the Stuart Age(1603 -1714) ... 9

1.6. Women's Lives during the Eighteenth Century ... 10

1.7. Women and the Idea of Close Family in the Nineteenth Century ... 11

1.7.1. The Rights of Women and the Law ... 11

1.8. Women's Lives in the Early of Twentieth Century ... 13

1.9. Women and Education before 1914 ... 13

2. The Political Status of Women before WW1 ... 15

2.1. Women and Party Politics ... 16

2.2. The Right to Vote ... 16

2.3. Women’s Suffrage Movements and Organizations ... 17

X

2.3.2. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS, NU) ... 18

2.3.3. London Society for Women’s Suffrage (LSWS) ... 19

2.3.4. People’s Suffrage Federation ( PSF ) ... 19

2.3.5. Women’s Freedom League ( WFL ) ... 19

Conclusion ... 20

Chapter Two꞉ The Impact of World War One on British Women Introduction ... 23

1. The Social Impacts of the First World War on British Women ... 24

1.1. The First World War and the Escaping of Women from the Style of Daily Domesticity ... 24

1.2. Women and the Freedom ... 25

1.3. Women during the War ꞉ Misery and Gender Difference ... 25

1.4. Women and Sexual Freedom during World War One ... 26

2. Women’s Economic Role during the War ... 27

2.1. Women Workers in the Factories ... 29

2.2. Women Workers in Tank Production... 31

2.3. The Resistance of Women to Pass the Rent Restrictions Act ... 31

2.4. Women in the Land Army ... 33

2. 5. Women Workers in the Hospital ... 35

2.6. Women Workers as Voluntary Aid Detachment(VADs) ... 35

XI

2.8. Urging Women to Study Home Economics ... 37

3. The Political Impact of the First World War on Women of Britain ... 37

3.1. Women's Electoral Rights During and After the War ... 38

3. 2. Women in Parliament ... 38

3. 3. Attitudes of the Suffrage Movements During the war ... 39

3. 4. Different Views on the Impact of the Great War on Female Suffrage ... 41

4. The Military Contribution of British Women to the War Effort ... 42

Conclusion ... 45

Chapter Three : The British Women between the Dream of Liberation and the War Obligation Introduction ... 47

1. The Acts of Government꞉ Improvement or Limitation ... 48

1.1. The Munitions Act of June 1915 ... 48

1.2. The Rent Restriction Act of 1915 ... 49

1.3. The Restoration of Pre-War Practices Act in 1916 ... 50

1.4. The Maternity and Child Welfare Act In 1918 ... 50

2. Women and Discrimination꞉ Class Division, Paid Employment and Lower Pay ... 52

2.1. The Impact of the War on Women’s Employment ... 53

2.1.1. Industry... 55

XII

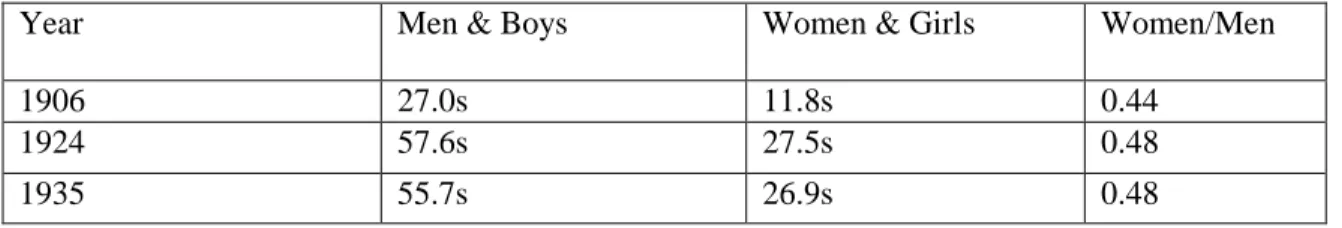

2.2. The Struggle for Wage's Equality and the Impact of the War on the Gender Wage Gap

... 57

2.3. Women Reaction against Wage Discrimination ... 58

3. Forcing Women to loss their Wartime Jobs and Return into Trades ... 60

4. The Myth of Women's Liberation after the War ꞉Reality or the War Obligation ... 61

Conclusion ... 62

General Conclusion ... 64

References ... 66

1

General Introduction

1. Background of the Study

The majority of writings about British women during the First World War tend to focus on their roles, and how their lives changed after the war. Before the World War One, most women were banned from voting or serving in military combat roles. During the war, many saw that women had more opportunities to not only serve their countries, but also to gain more rights and independence. With millions of men away from home, women filled manufacturing and agricultural positions on the home front. Others provided support on the front lines as nurses, doctors, ambulance drivers, translators and, in rare cases, on the battlefield. This research is meant to add another specific point vis-à-vis women's status in Britain during the First World War with attempt to consider the main factors involved in the change of the status of women.

2. Statement of the Problem

By the outbreak of the First World War, the lives of many women in Britain have changed due to new circumstances. Many women volunteered on the home front as꞉ nurses, teachers, and worked in traditionally male jobs and they suffered immensely in their work because they worked in dangerous places. However, all this disappeared when the war ended which means that what British women had done in the war faded from their immediate memory, and once more they started suffering from unemployment, humility, poverty and the rise of fascism. This led numerous historians to argue whether the impact of World War One on the British women was a sign of their liberation or it was just the war obligation.

2 3. Aim of the Study

The present dissertation simply aims to highlight both the most changes of women's lives in Britain during the First World War and the reality behind those changes.

4. The Significance of the Research

This study attempts to show that British women were used as a solution to serve the country and to replace the men in many aspects during the First World War which has bearing on the status of women in that felt free. But, they suffered a lot and their freedom disappeared by the end of the war.

5. Research Questions

The aim of this study is to provide satisfactory answers to the following research questions꞉

1.Did the First World War affect British women's lives? How?

2.Did women's status during the First World War represent their freedom? 3.Did the British women enjoy the same status by the end of this war?

4.Why did Britain provide the women with the opportunity to practice some rights during the WW1?

6. Research Hypotheses

This dissertation is built on the following idea꞉ there are hidden reasons behind the change in the status of the British women during the First World War.

In addition, all the changes took place during the war years were resulted from the obligation of the war since there was an urgent need for woman to help in that difficult situation. Therefore, women's liberation was temporary during the war because it did not continue after the war.

3 7. Research Methodology

In order to obtain relevant information concerning this topic and to get clear answer to the previous questions, the qualitative research is used to collect the accurate data through reading some various references such as books, articles and websites which serve the aim of the study, in addition to the descriptive analytical method to trace the important events during the war period given the fact that this method, through a process of data collection, enables the researcher to describe the situation more completely.

8. Structure of the Dissertation

In order to cover all the main points concerning this topic, this dissertation starts with general introduction which explains the main idea of this topic and provides the reader with an overview about the topic. Next, the research is organized into three chapters. The first chapter gives a general idea about women's lives in Britain before the First World War, chapter two presents the status of women during the war period. The third chapter which is the last one discusses and analyses the nature of this status. Finally, this work ends with general conclusion which summarises the main findings of the study.

Chapter One: The Status of British Women before

5

Chapter One: The Status of British Women before the First

World War

Introduction

For many years and from the overview of some people, the word women, girl, daughter, mother, sister, or any other word that is related to females, is just a word which has no value in their minds. But, in reality, this word is not just a word as they considered it. It is everything in the life, it is the light of everyone in the family, and without women life is difficult and may not continue.

Unfortunately, many women suffered a lot and they were victims in many societies in the world among the centuries. Some of them suffered from the authority of parents, others were victims under the power of husbands because some of them did not recognize the woman's value and according to them the woman is nothing. Also, the law sometimes was not with women and they did not obtain their rights socially, politically and economically.

The First World War in 1914 was a chance for many women in the world to give themselves an opportunity to fulfill prominent roles in their societies in order to change the difficult conditions they had been living in before this time. The British women were one of those women; their lives differed from century to another and from society to another.

This chapter sheds light on the life of women in Britain before the World War One. It provides a sound basis of comparison between the status of women in the early years of the twentieth century and the earlier centuries. Furthermore, it should be worth noting that this chapter lays emphasis on the political and social status of women since it is impossible to encompass all the series of events that took place during that difficult period.

6

1. The Social Status of Women in Britain before the First World War

1.1. Women's Lives during the Celtic Period

The British women during that period might have more independence than they had before because when the Romans invaded Britain two of the largest tribes were ruled by women who fought from their chariots (McDowall, 1989).

One of those famous women was Boadicea, or as she is known Boudicca, she was the widow of the king of the Iceni in eastern Britain who had been allied with Rome. Leaving two daughters and no son (Burns, 2010, p. 14). She had become queen of her tribe when her husband had died (McDowall, 1989, p. 8).

In AD 61,Boudicca led her tribe against the Romans. She nearly drove them from Britain, and she destroyed London, the Roman capital (McDowall, 1989, p. 8). Her subsequent rebellion was the greatest challenge to Roman rule in Britain. The rebellion at first seemed successful, particularly since the main Roman army at the time was battling the rebellious Silures on the island of Anglesey off the west coast of Britain. Boudicca’s forces attacked and burned the Roman provincial capital, Camulodunum, the old Catuvellaunian capital, massacring its inhabitants. The rebels also burned London, although the population was evacuated. However, they were not able to face a full Roman army the rebellion was crushed when 10,000 Roman troops slaughtered80,000 Britons in the Battle of Watling Street, and Boudicca committed suicide rather than become a prisoner of Rome. The rebellion resulted in the transfer of Roman provincial administration to London (Burns, 2010 , p. 14).

Boudicca's story reflects the difficult conditions which many women faced during that period in Britain. Moreover, it reflects how those women suffered a lot to get their rights

7

and to protect their country. But, the end of Boudicca's life was horrified because she is a woman.

1.2. Women's Marriage without Respecting the Family's Relation for Keeping the Family's Property (The Anglo -Saxon)

The Kinship practices of Anglo –Saxon differed from those of the Christian British because they did not respect some family's relationship, especially in some issues concerning the marriage. One of their horrified practices was that they allowed a man to marry his stepmother on his father’s death in order to protect property in the family. In addition, they were able to divorce, a practice forbidden by the church (Burns, 2010).

1.3. In the Middle Ages: Women under the Authority of Men

The life of women in the Middle Ages was hard because Church taught that women should obey their husbands. It also spread two very different ideas about women: that they should be pure and holy like the Virgin Mary and Eve, they could not be trusted and were a moral danger to men. Such religious teaching led men both to worship-and also to look down on women, and led women to give in to men's authority (McDowall, 1989).

1.3.1. Women and Marriage꞉ Women's Marriage as a means for the Family's Wealth Marriage was usually the single most important event in the lives of men and women. But the decision itself was made by the family, not the couple themselves. This was because by marriage a family could improve its wealth and social position. Everyone, both rich and poor, married for mainly financial reasons. Once married, a woman had to accept her husband as her master. A disobedient wife was usually beaten. It is unlikely that love played much of a part in most marriages (McDowall, 1989, p. 62).

8 1.3.2. The Life of Married Women

The responsibility of woman after she become wife is onerous and more complex because she was obliged to do many things and hold many responsibilities.

The first duty of every wife was to give her husband children, preferably sons (McDowall, 1989, p.62 ) because women were inferior as they menstruated and incomplete until they bore a child (Davis, 2014). Yet, this was the future for every wife from twenty or younger until she was forty (McDowall, 1989).

Most women, of course, were peasants, busy making food, making cloth and making clothes from the cloth. They worked in the fields, looked after the children, the geese, the pigs and the sheep, made the cheese and grew the vegetables. The animals probably shared the family shelter at night. The family home was dark and smelly. Woman’s position improved if her husband died. She could get control of the money her family had given the husband at the time of marriage, usually about one -third of his total land and wealth. But she might have to marry again: men wanted her land, and it was difficult to look after it without the help of a man (McDowall, 1989, p. 63).

However, the responsibilities of the wife of noble differ from ordinary women’s ones because the former had other responsibilities when her lord was away. Some of these responsibilities were ꞉

▪ When her lord was away, she was in charge of the manor and the village lands, all the servants and villagers, the harvest and the animals.

▪ She also had to defend the manor if it was attacked. She had to run the household, welcome visitors and store enough food, including salted meat, for winter.

▪ She was expected to have enough knowledge of herbs and plants to make suitable medicines for those in the village who were sick.

9

▪She probably visited the poor and the sick in the village, showing that the rulers cared for them. She had little time for her own children, who were often sent away at the age of eight to another manor, the boys to "be made into men" (McDowall, 1989).

1.4. Women's Lives during the Tudor Period (1485-1603)

The unmarried women suffered during that period. Before the reformation many of these women could become nuns, and be assured that in the religious life they would be safe and respected. After the dissolution of the monasteries, thousands became beggars on the roads of England. Also, Life of married women was not easy because most of them bore between eight and fifteen children. In addition, many of them died in childbirth, and because marriage was often for economic purposes and it had often no relation with emotions (McDowall, 1989).

Although this dark side to those women, Foreign visitors were surprised that women in England had greater freedom than anywhere else in Europe. Although they had to obey their husbands, they had self-confidence and were not kept hidden in their homes as women were in Spain and other countries. They were allowed free and easy ways with strangers (McDowall, 1989, p. 85).

1.5. Women between the Authority of Husbands and Parents in the Stuart Age (1603 -1714)

By the end of the sixteenth century there were already signs that the authority of the husband and the father was increasing. As a result, the loss of legal rights by women over whatever property they had brought into a marriage (McDowall, 1989). In addition, the protestant religion gave new importance to the individual, especially in Presbyterian Scotland. Many Scottish women were not afraid to stand up to both their husbands and the

11

government on matters of personal belief. In fact many of those who chose to die for their beliefs during Scotland 's "killing times" were women. This self-confidence was almost certainly a result of greater education and religious democracy in Scotland at this time (McDowall, 1989, p. 105).

1.6. Women's Lives during the Eighteenth Century

There were contradictions about women’s lives in British society. This paradox is illustrated by the 1864 painting by Rossetti entitled The Blessed Beatrix'. This beautiful image of his wife, Lizzy Siddal, contrasts harshly with Rossetti's treatment of her, a woman whom he had betrayed through numerous affairs and who had poisoned herself the year before( Malcolm & Geoffrey,1992).

The working female, in eighteenth-century in Britain, was ubiquitous, to be found laboring in most fields, workshops, town streets, and homes. However, women's employment in that period was invisible in the sense that it is 'hidden from history', and less likely than men's who have left a mark on the historical record (Barker, 2016).

From another hand, the richest women's lives were limited by the idea that they could not take a share in more serious matters. They were only allowed to amuse themselves. As Philip Stand hope wrote: "Women are only children of larger growth . . . A man of sense only plays with them. . . he neither tells them about, nor trusts them with serious matters"(McDowall, 1989, p. 116).

In the eighteenth century, girls were victims of the parents' desire to make them match the popular idea of feminine beauty of slim bodies, tight waists and a pale appearance in order to get a chance of good marriage. For this purpose, parents forced their daughters in to tightly wasted clothes, and gave them only little food to avoid an unfashionably healthy appearance (McDowall, 1989).

11

1.7. Women and the Idea of Close Family in the Nineteenth Century

It was remarkable that the truism that “a woman’s place is in the home” was repeated frequently in the century after 1850 (D’Cruze, 2006).

The eighteenth century saw a spread of the idea of the close family which was under the master of the household. As a result, this limited the possibility for a wife to find emotional support or practical advice outside her family. Also, many women found their sole economic and social usefulness ended and family life often ended when their children grow up. As one foreigner noted in 1828,"grownup children and their parents soon become almost strangers ". In addition, in that century women were discouraged from going out to work if not economically necessary, they encouraged to make use of the growing number of people available for domestic life that means a wife was legally a man's property(McDowall, 1989). As someone wrote in 1800, "the husband and wife are one. and the husband is that one" (McDowall, 1989, p. 137).

However, The social construction of medical knowledge is particularly fascinating when concerned with women’s health in the Victorian (1837-1901) and Edwardian (1901-1910) periods (Macnicol, 1988).

After1871, the census showed that there were slightly more women than men in the population (D’Cruze, 2006, p. 48).This resulted from the emigration of men. Most Britons, whatever their political persuasion, wealth or gender, believed woman’s place was the home, where indeed most nineteenth-century women spent a great deal of their time, thanks to frequent childbirth (Farmer, 2011).

1.7.1. The Rights of Women and the Law

Victorian women were battered, frequently denied property rights and denied the right to vote (Malcolm & Geoffrey,1992, p. 14) as well as managing their households, women

12

were responsible for carrying out or supervising the housework. In the nineteenth century, domestic work was arduous, physically demanding and time consuming. This was true whether it was done by servants in a middle-class or upper-class household, or by wives, mothers and daughters without cash payment in working-class or lower middle-class homes (D’Cruze, 2006, p. 56).

It was almost impossible for women to get a divorce, even for those rich enough to pay the legal costs. Until 1882, a woman had to give up all her property to her husband when she married him. And until1891, husbands were still allowed by law to beat their wives with a stick "no thicker than a man's thumb", and to lock them up in a room if they wished. By 1850, wife beating had become a serious social problem in Britain. Men of all classes were able to take sexual advantage of working women (McDowall, 1989, p. 162).

According toBurns ( 2010)꞉

Under the English common law, a married woman could not possess property in her own name; unless special arrangements were made, her property was considered that of her husband. If a woman was stuck in a bad marriage, divorce was very difficult. It was almost impossible for a woman to divorce and receive custody of her children if the husband wanted to keep them. ( p. 171)

Malcolm and Geoffrey (1992) stated that the government of Great Britain in the 1860s was not perfect, but it did not only consider the male interest. A Parliament of men still passed the Criminal Law Procedure Act in 1853 to try to end the evil practice of wife beating and in 1878 the Matrimonial Clauses Act facilitated divorce for ill-used wives. Successive Married Women's Property Acts were to be passed to give married women the right to own property themselves even if they still had no vote (p. 20).

13

A number of significant Acts of Parliament were passed. The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 allowed divorce without the need for a separate Act of Parliament, but on unequal grounds. The Married Women’s Property Acts in 1870 and 1882 eroded the legal doctrine of

covertures, which stated that a married woman’s property was owned by her husband. These

Acts gave married women the right to control their own earnings and property (D’Cruze, 2006, p. 65).

1.8. Women's Lives in the Early of Twentieth Century

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century there was a loss of women from the countryside. This was a result of the undervaluation of women in the farming industry and the belief that women could find better employment opportunities in the towns and cities. This does not mean that women ceased to play an integral part in farm life. In the early twentieth century family farms were labour intensive, and with a shrinking domestic market and agricultural labour force, hiring outsiders was unprofitable for both men and women, the farmer’s female relatives were called upon to fill the labour gap. Their work were limited including feeding animals, caring for the household and children, and operating some machinery that had traditionally been operated by men. While their work expanded in the early of the same century, Women did not wear trousers, they did not climb trees, and few ventured alone to the market to sell the family’s wares. Wives assisted their husbands and while the gender division of labour on farms was lessening, it remained securely in place at the outset of the First World War (White, 2014).

1.9. Women and Education before 1914

At least until the First World War, the majority of girls in Britain received a crucial part of their education in the home. Carol Dyhouse argues that there was a strongly held

11

notion of schooling as encouraging academic aspirations in girls, undermining their attachment to home and to the domestic duties. All women were expected to conform to the ideology of domesticity, which disapproved of working women and which located feminine virtue in a domestic and familial setting. Domesticity, however, differed according to class, which had implications for female education. Middle-class women were ladies, for whom waged work was demeaning, indeed a slur on middle-class manhood. Middle-class girls’ education, therefore, had to correspond to their status: it should inculcate the domestic ideal; and it should also polish the young lady through training in the social graces, which would render her competitive on the marriage market. There was no need for a grammar school or university education, whose function was to prepare middle-class boys for service to Church or state (McDermid, 2006,).

Middle- and upper-class women in the 19th century could not be educated past the equivalent of high school, and they were educated to that level at a much lower rate than men. They could not participate in the recognized professions in law, medicine, or the church. In addition,in middle class familly would sacrifice and go without an education in order to support the sons properly. But, after the mid-19th century The situation began to improve because the expansion of the educational sector offered more women the opportunity to be teachers, a relatively more respected profession, but options were still very limited (Burns, 2010).

There were many education acts and movements concerning women's education in Britain which appeared before 1914 in order to improve, facilitate and pave the way into women and girls education. England led the way in reforms of middle-class girls’ education. Two major parliamentary investigations, the Taunton Commission of the 1860s and the Endowed Schools 'Commission of the 1870s, led to improvements for middle-class girls’

15

schooling in both England and Wales. The Taunton Commission noted evidence which showed that the mental capacity of the sexes was virtually the same, though the education of middleclass girls before the mid-nineteenth century was, at best, frivolous, with an emphasis on the social graces (McDermid, 2006).

By the last third of the 19th century, and as a resulted of this movement women began receiving medical degrees. Among those women who obtained a medical degrees were꞉ Dr. James Barry, Elizabeth Blackwell, Elizabeth Garrett (1836–1917) the first British woman to be qualified and to practice medicine in Britain. But the Entrance into higher education involved choices. At first, some advocated a separate curriculum for women in higher education with less study of classical languages, math, and science and more domestic skills, such as needlework. In addition, the idea of female students which was that the entry of women into their institutions would lower their status . but this began to change during and after World War (Burns, 2010 ).

It was virtually impossible to refute the medical and religious arguments against higher education for women in the late-nineteenth century. There were in addition economic arguments against it, including the fear of introducing competition between the sexes for the professions, and the claim that higher education for women was an unsound investment, since they would stop work on marriage women’s supreme profession (McDermid, 2006, p. 95).

2. The Political Status of Women before WW1

Before the Great War, a woman’s role was considered to be within the home. Public life, including politics was widely seen as for men only. It was believed that women involved in politics would neglect their responsibilities at home (“Domestic impact of World War One - society and cultureˮ, n. d).

16

However, there were women political thinkers, like Mary Wollstonecraft, who wrote in sophisticated and complex terms about the political thoughts issues that pervaded the early-modern era, such as the separation of church and state, toleration, different constitutional forms and the contract theory of government (Armitage, 2006).

2.1. Women and Party Politics

From the 1870s, although women were denied access to the parliamentary franchise, they did have the opportunity to take part in political life at a local level as candidates for school boards, boards of guardians, parish councils and later county councils. They stood as independent candidates and also as representatives of particular parties. However, the male-dominated political parties put forward contradictory messages in their attempts to attract women to their cause (Hannam, 2006).

Women also joined the socialist groups which were established in the late nineteenth century and worked for the Labour Party after 1900. This immediately raised the issue of what women’s role should be, and whether they should organize separately in order to create their own political identity (Hannam, 2006, p. 191).

2.2. The Right to Vote

According to Simkin (1997), in 1865 a group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Society. The women thought it was unfair that women were not allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. They therefore decided to draft a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote. They took their petition to Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill, two MPs who supported universal suffrage. Mill added an amendment to the 1967 Reform Act that would give women the same political rights as men. But the Mill’s amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73 in the house of commons (para.1-3).

17

In 1897 women started to demand the right to vote in national elections. Within ten years these women, the "suffragettes", had become famous for the extreme methods they were willing to use (McDowall, 1989).

However, “If women could not vote, it was because they were generally held to be emotionally and intellectually unsuited to the task. It was also held that their husbands and fathers could effectively exercise the vote for them” (Malcolm & Geoffrey, 2002, p. 19).

2.3. Women’s Suffrage Movements and Organizations Burns (2010) said that:

A women’s movement, dominated by middle-class women and their concerns, emerged in mid-19th- century Britain for several reasons. Literacy and education among women was increasing. The organization of women taking part in political and humanitarian campaigns and for charitable work that increased women’s and men’s awareness of problems caused by lack of education, access to the professions, and the vote. The key to suffragist and women’s rights activities generally was the organizing of large numbers of mostly middle-class women. (p. 172)

However, "parliamentarians spared little attention for the women’s cause” (Vellacott, 2007, p. 2).

From the late of eighteenth century many women’s movements and organizations had been founded, some of them are mentioned below:

2.3.1. Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU)

The WSPU was the largest radical suffrage organization, founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia (Burns, 2010). The founding of

18

the WSPU was followed by a wave of militant suffrage activism. The members of which became known as the suffragettes (Myers, 2013).

“The leading members of the WSPU, a militant suffrage group, severed their links with the Labour Party in 1907 and were actively hostile to Labour Party candidates during election” (Hannam, 2006, p. 196).

2.3.2. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS, NU)

The NUWSS had been formed in 1897, as the result of the coming together of two London-based groups, and the formation of a federation of local societies across the country. It was a development of the First Women’s Suffrage Society which was founded by John Stuart Mill, Mrs. P.A. Taylor, Emily Davies, and others (“John Stuart Mill - The later yearsˮ, n. d). Three years later their leader would be Millicent Garret Fawcett (Myers, 2013).

During its first ten years, the growth of the movement took place mainly at the periphery; in the North of England in particular. Outreach was to men as well as to women, on the logic that the support of those who had the vote was needed (Vellacott, 2007, p. 1).

From 1903, when the NU convened a National Convention in Defence of the Civil Rights of Women, the organization took a more active role in the parliamentary constituencies, with local committees pressing parliamentary candidates to pledge their support if elected. The NU continued until 1910 to be dominated mainly by London suffragists who are the members of the London Society for Women’s Suffrage (Vellacott, 2007).

19

2.3.3. London Society for Women’s Suffrage (LSWS)

It was formed by members of the Kensington Society after Mill amendment was defeated. John Stuart Mill became president and other members included Helen Taylor, Lydia Becker, Emily Davies, and others (Simkin, 1997).

Like the NU, the LSWS made efforts to place needy women in work, setting up a useful Employment Exchange (Vellacott, 2007, p. 34).

2.3.4. People’s Suffrage Federation ( PSF )

The PSF was created by a merger of the Co-operative Women's Guild and the Women's Labour League in 1909—and led by Margaret Llewelyn Davies. The group believed that the Women's Suffrage movement was being damaged by class divisions, such as those that split the Women's Social and Political Union and the Women's Freedom League. They also thought that universal suffrage would be more popular with the liberal Government, as it was likely that voting rights only for privileged women would likely increase the conservative vote (Smith, 1998).

2.3.5.Women’s Freedom League ( WFL )

It was founded by Charlotte Despard and Teresa Billington-Grieg in 1907 (“Suffragettes - Timelineˮ, n. d, p. 1). It attracted the support of many socialist suffragists and a significant number of the WSPU’s branch societies. The WFL, while formally non-party in its affiliations, remained close to the Independent Labour Party (Holton, 2006, p. 247).

The WFL kept its focus on suffrage and feminism, and was vocal on all questions of women’s rights. The WFL worked on the same issues taken up by the NU (Vellacott, 2007).

21

In 1851, the Sheffield Female Political Association was formed and brought a petition in

support of enfranchising women to the House of Lords

In 1865, the Kensington Society was founded as a discussion space for supporters of

enfranchising women

In 1867, the Manchester Suffrage Committee was founded (a precedent for Manchester’s

pivotal role in the suffrage movement)

Also in 1867, the Kensington Society became the London National Society for Women’s

Suffrage

In 1871/2 the Central Committee of the National Society for Women's Suffrage was

established

In 1883, the Primrose League (a Conservative group) were established

In 1886 the Women’s Liberal Federation was formed

In 1889, the Women’s Franchise League was formed

In 1906, the National Federation of Women Workers is established (Myers, 2013).

Conclusion

In the pre-war years, British woman was considered inferior and her role in society was to look after her house, kids, and husband. Although women missed many rights, they should keep their mouths shut. The men mistrusted women in doing serious works like political activities as they were seen not as clever as men. Working class women suffered greatly in their lives; however, women from middle class lived in better conditions than the other British women. Women wanted to be treated as equal as men; therefore they started to call for their rights.

21

In the eighteenth century, some women did work as doctors, lawyers, teachers, and writers. But, by the early nineteenth century, they were domestic servants in factories. To sum up, despite the harsh conditions women had been facing in Britain, they were seen more free when they were compared to women from other countries like France and Germany.

Chapter Two: The Impact of World War

32

Chapter Two꞉ The Impact of World War One on British Women

Introduction

Broadly speaking, all the wars in the world had great impact on everyone in society, and may create and require new condition for life. The First World War was one example of those wars which was in the period from 1914 to 1918, this war also had strong effect on every member of the family in the world. Especially, the women because this war was as a starting point to change lives of many women and it was a turning way for most of them. Women in Britain were one of those women who were influenced by this war.

Women's participation during the Great War changed the lives of women in Britain from housewives, mothers and girls into workers outside their home to replace the men because they had gone to fight in that period. Consequently, a large number of British women felt free with this new status which opened to them opportunities to do many things and help them to obtain their rights. Therefore, this new life made many women tasted the freedom as many historians described it.

This chapter sheds light on the status of women in Britain during The First World War in all the aspects. Furthermore, it traces the crucial role of those women during this war. In addition, this chapter explains how the women in Britain adapted to the situation and what their reaction was. This chapter includes also some examples of famous British women during this war will be mentioned.

32

1. The Social Impacts of the First World War on British Women

It was remarkable that the First World War had great impact on women's lives in Britain due to the fact that this war had changed their status socially, politically, and economically. During the war, women were compelled to undertake onerous responsibilities. Hence, women had crucial roles in protecting their families and country.

The war forced a new independence and enterprise on women. Many became accustomed to having more responsibility within the home. The challenge to the myth of male work skills, resulting from women's war work, may have generally served to undermine masculine assumptions of authority (Farmer, 2011, p. 228).

1.1. The First World War and the Escaping of Women from the Style of Daily Domesticity During the war, women undertook a variety of jobs previously done by men. Some historians claim that this increased women’s self-confidence. It certainly gave some women more economic independence and a legitimate excuse for escaping from the confines of domesticity. However, it is possible to claim that the war’s positive effects on women’s status have been exaggerated because women rarely did skilled work and were usually paid much less than men. This only ‘increased antagonism between the sexes’, says DeGroot, ‘and, needless to say, did nothing for gender equality’. The notion that the war revolutionized men’s minds about the sort of work of which women were capable may well be a deception. Traditional views of women’s role remained strong. Moreover, if most men continued to think women’s place was at home, many women agreed. Indeed, the war may have strengthened the ideology of domesticity. Motherhood was increasingly presented as an honorable state service, akin to soldiering. Several

32

women’s organizations developed this line of argument in support of family allowances and state subsidies for child-bearing mothers – money that would encourage women to stay at home. In addition, the horizons of many young women broadened after 1914 (Farmer, 2011).

1.2. Women and the Freedom

The liberation of women took other forms. They started to wear lighter clothing, shorter hair and skirts, began to smoke and drink openly, and to wear cosmetics. Married women wanted smaller families, and divorce became easier, rising from a yearly average of 800 in 1910 to 8000 in 1939. Undoubtedly, many men also moved away from Victorian values. Leading writers like D.H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf freely discussed sexual and other sensitive matters, which would have been impossible for earlier generations (McDowall, 1989, p. 163).

1.3. Women during the War꞉ Misery and Gender Difference

For many women, the war brought heartache and loneliness rather than a great release. Constant anxiety over the fate of loved ones often culminated in the agony of bereavement. In the longer term women had to endure another of the war’s legacies: a worsening of the gender imbalance. Among those aged 20–34, the female surplus rose from 463,000 in 1914 to 773,300 in 1921. Thanks to the war one woman in six could look forward to a lifelong spinsterhood (Farmer, 2011, p. 218).

32

1.4. Women and Sexual Freedom during World War One

The war may have led to free sexual relationships. Perhaps some young women were tempted to have a last fling with boyfriends before they went to the front. Some were convinced that this encouraged a rise in the illegitimacy rate (from 4.3 per cent in 1913 to 6.3 per cent in 1918). There were press outcries at the numbers of single women expecting ‘war babies’ in areas where large numbers of troops were stationed. But the rise in illegitimacy may have been simply a reflection of the obstacles presented by the war to the common practice whereby men agreed to marry women if they became pregnant. More worrying than the rise in illegitimacy was the increase in venereal disease, which affected something like one soldier in five. French co-operation in organizing brothels, with some rudimentary medical control, was not enlisted until 1916. Protective sheaths were not issued to the troops until 1917. Through wider distribution of sheaths more married couples probably became familiar with contraception during and immediately after the war. But Marie Stopes’s book Married Love (1918), which popularized birth-control techniques, suggested in its title that it was concerned with marriage enrichment, not sexual pleasure for its own sake. Women perhaps came to benefit from the growing use of contraception: it rescued some wives from a non-stop succession of pregnancies. But otherwise the war did not much advance the cause of sexual liberation (Farmer, 2011).

According to Robert Roberts [he was an English teacher and writer],whose parents at the time ran a corner-shop in a working-class area, women at the end of that war 'were more alert, more worldly-wise'. They then discovered that their husbands, returned from the war, 'were far less the lords and masters of old, but more comrades to be lived with on something like level

32

terms'. According to the novelist Evadne Price, in her fictional autobiography based on the genuine reminiscences of a nurse who served on the battle front, the war destroyed old-style sexual reticence (Marwick, 1991, pp. 11-12).

Sport, especially football, was encouraged among the new female workforce, and many munitions factories established their own ladies’ football teams. In 1918, knock-out competition the Munitionettes’ Cup attracted30 teams; matches drew crowds of tens of thousands of spectators and raised large sums of money for the war effort. Despite their popularity, in 1921 the FA banned women’s football matches at their grounds, and this ban was only lifted in 1971.Teams such as the Cumbria Munitionettes from Lonsdale in Cambrian used the matches to raise money for the war effort and for wounded soldiers contribution (World War

One at home, n. d, chapter 3).

Sport during the war in Britain helped the country economically and encouraged the woman socially in order to escaping from the daily routine of domesticity.

2. Women’s Economic Role during the War

In 1914, Suffragette groups suspended their campaign for women's right to vote, demanding instead that they would be allowed to serve the country by undertaking work that would release men for military duty. Trade union opposition initially made this difficult because they feared that female labour would reduce wages for men. But as the labour shortage intensified and the principle of dilution was accepted, women began to find work. The number of females employed in munitions production rose from 82,859 in July 1914 to 947,000 by November 1918. Some 200,000 women entered government departments and 500,000 took over

32

clerical work in private offices while the number of females in the transport sector rose from 18,200 to 117,200. As a result, Munitions work offered more freedom and better remuneration. Work in munitions industries would also end when the war ended. In 1918, five-sixths of women were still doing what was considered to be ‘women’s work’. While the number of domestic servants declined by 400,000, most women were still employed as domestic servants. But, Women still earned substantially less than men doing the same work (Farmer, 2011).

The moralizing campaigns were designed to induce guilt in mothers who did paid work, many of whom, as we have seen, had little choice if they were to maintain themselves and their children above the poverty line. But, in this atmosphere, the reformists’ concerns also led to policy changes. The Maternity and Child Welfare Act passed in 1918 enabled local authorities to find maternity homes, infant welfare centers and crèches, and to provide salaried midwives and health visitors as well as milk and food for mothers and children. These provisions must have been welcomed by many mothers. However, the WCG and other women’s organizations argued that what mothers needed above all, in order to improve their health, as contraception. In spite of evidence of the appalling effects of too many births too close together on both women and children, the postwar clinics were not allowed to offer a contraceptive service. The limitations of the wartime improvements in the conditions of motherhood are suggested by the fact that the rate of maternal mortality remained stubbornly high throughout the interwar years (Summerfield, 2006).

32 2.1. Women Workers in the Factories

After the introduction of conscription in March 1916, the government encouraged women to take the place of male employees who were serving at the front. By 1918 nearly one million women were employed in engineering and munitions industries. Known as Munitionettes - these women became the poster girls for the war effort and were frequently photographed and filmed to emphasize the importance of their contribution to the war effort (World War One at home, n. d, chapter 3). In addition, Women were required to make a significant contribution during the First World War. As more men left for combat, women undertook 'men's work'. The government used propaganda films to encourage women to get involved, for instance, women worked in farms and factories (Anitha & Pearson, 2013).

Mcdowal (1989) mentioned that the war in 1914 changed everything. Britain would have been unable to continue the war without the women who took men 's places in the factories. By 1918, 29 percent of the total workforce of Britain was female (p. 163).

Many of the female workers at the vast shell filling factory in Chilwell in the suburbs of Nottingham lived in an industrial complex that was like a small city, with its own power station, 125 miles of railway track, 34 railway engines, giant laundries, a ballroom, a cinema, two purpose-built townships, and kitchens producing 14,000 meals and 13,000 loaves of bread a day and Long shifts were commonplace in the factories and there are reports of women passing out after working 12 hours continuously, without eating. They formed a third of the 80,000 strong workforce at The Royal Arsenal in Woolwich in London. Although employment was generally regarded as well paid, female workers did not receive the same wages and benefits as their male

23

counterparts. They often found themselves doing jobs that had been simplified into a series of unskilled tasks (World War One at home, n. d, chapter 3).

Work in the factories was hazardous. Employees handled explosives and noxious substances known to cause a range of medical disorders, from skin complaints to bone disintegration. Manufacturing mustard and other gases was particularly perilous; sickness rates were so high at HM Factory [National Filling Factory which is known HM Factory was established by the Ministry of Munitions in 1917] in Chittening Road in Bristol that workers were entitled to one week of holiday for every 20 days worked. In Gretna in the Scottish borders, Women working at HM Factory produced nearly a thousand tones of the explosive, cordite, per week. They used their bare hands to mix concentrated acid with cotton and solvent to make what became known as ‘the devil’s porridge'. Life in the factories wasn’t just making ammunitions; these were communities of workers from all parts of the country. Many were young girls, away from home for the first time, and living together in hostels (World War One at home, n. d, chapter 3).

23

Figure 1 shows the work of women in the shell factories in Britain during the World War One. It reflects how women were able to replace the man in the work place during the war period.

Those women who worked in the munitions factories were Known as ‘canaries’ because they had to handle TNT (the chemical compound trinitrotoluene that is used as an explosive agent in munitions) which caused their skin to turn yellow, these women risked their lives working with poisonous substances without adequate protective clothing or the required safety measures. Around 400 women died from overexposure to TNT during WWI (Anitha & Pearson, 2013).

2.2. Women Workers in Tank Production

Tank production was hot, heavy, dangerous work that now included women, working in heavy industry for the first time. They worked 12-hour shifts, taking over from each other to ensure 24-hour cover, even eating their sandwiches at their machines in the factory. Among the Tank girls in the war years꞉ Florence Bonnet and William Foster(World War One at home, n. d, chapter 4).

2.3. The Resistance of Women to Pass the Rent Restrictions Act

The wartime state was prepared to concede under duress. In 1915 the Glasgow Women’s Housing Association took direct action to prevent the eviction of a soldier’s family unable to pay the rent. Armed with peas meal flour, women mounted angry pickets, with street after street joining the rent strike. As discontent spread beyond Glasgow, the government introduced the Rent Restriction Act (Rowbotham, 2018).

23

A working class woman from the district of Gavan in Glasgow called Mary Barbour led some of the most successful resistance to rent increases. Barbour established tenants 'committees and organized rent strikes in which her supporters,known as ‘Mrs. Barbour’s Army’, worked as a team Women were posted as sentries to watch out for the Sheriff's officers coming to evict families who had fallen into rent arrears. A bell or the sound of a football rattle would then summon a larger crowd who would form a scrum to prevent officers gaining entry to houses, often pelting them with flour or rotting food. By November there were twenty thousand tenants on strike and on 17 November 1915, a crowd of thousands of women, along with engineers and ship workers,gathered at Glasgow Sheriff Court and the City Chambers in protest.A month after the November 1915demonstration Parliament passed into law the Rent Restrictions Act, setting rents for the remainder of the war at pre-war levels (World War One at home, n. d, chapter10).

When women appeared doing “men’s jobs”, skilled men were inclined to view them as interlopers, likely to enable employers to damage craft differentials. And this was indeed what happened in some factories. But the new recruits would also assert themselves in the workplace. In July 1918, male and female munitions workers in Coventry took strike action together. In that last year of the war, when women bus and train workers went on strike, the slogan, “Same work, same money” appeared. When the strikes spread from Hastings to Bristol, to Birmingham and South Wales, the authorities intervened with a five-shilling bonus, though not equal pay (Rowbotham, 2018, para. 08).

22 2.4. Women in the Land Army

The war years brought with them sweeping changes to the production of food. There was an army to feed, and many of the skilled farm workers had joined the army. By 1915 German U-boats were blockading the British coastline, preventing the import of food and threatening to starve the country, which prior to the war, had relied heavily on food from abroad. These stories show how everyone – from the Women’s Land Army to scouts and schoolboys –as one group, utilizing every corner of the land to ‘grow for Britain’ (World War One at home, n. d, chapter 5).

Well over 100,000 volunteered for the Women’s Land Army, ruffling the gender norms of rural Britain. Others enlisted in the Women’s Royal Naval Service, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps or the Women’s Royal Air Force as mechanics and drivers, cleaning, working in canteens or doing clerical work (Rowbotham, 2018, para. 04).

Women were a vital part of the drive to increase productivity on the land. From the start of the war women from all social classes responded to the need for help and volunteered to work on farms. As the war progressed, recruitment was formalized, and in 1917 the Women’s Land Army was established. Women were given four weeks training and went to farms around the country. By 1918, up to 260,000 women are reported to have worked as farm labourers, with over 16,000 working directly for the Land Army. They wore a distinctive uniform consisting of a tunic, breeches, boots and a felt cloche hat. They were expected to go wherever they were needed and they were paid 18 shillings a week for milking, taking care of livestock and general farm duties. This rose to 20 shillings when they passed an efficiency test (World War One at

22

The WLA, however, marked the first time that group of women came together in a national organization for farm work. The creation of the WLA was part of a broader effort to mobilize a domestic force of women workers, but with the specific task of replacing the male agricultural labourers who had enlisted or who had been conscripted into Britain’s armed forces (White, 2014, p. 01).

Women also worked to harvest crops such as flax which was used for cloth coverings for aircraft construction. For ten weeks of the year, hundreds of pickers descended on farms in the area around Yeovil in Somerset for the flax season. Women workers camped in tents or slept in the open air, attracting the attention of local townsfolk who would walk or cycle past to catch a glimpse of them. Picking flax by hand was far from easy and often left the women with festering hand sores. In woodland areas including Flaxley Woods in the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire, women took on the role of felling trees and cutting logs, and became known as ‘Lumber Jills’. In figure 2, members of the Women’s Forestry Corps grind an axe (World War One at home, n. d, chapter 5).

22 2. 5. Women Workers in the Hospital

Women in Britain during the First World War played a significant role to protect their country. They participated in the medical work in the military hospitals.

The Endell Street Military Hospital in Covent Garden in London was the only all-female run military hospital. Opened in May 1915 by suffragists Dr Flora Murray and Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson, the hospital became a specialist centre for head injuries and broken limbs, and even published clinical research. When it closed in August 1919, staff had treated 24,000 patients and performed more than 7,000 operations. The all-female staff proved what many had before doubted – that women could manage the medical and administrative needs of a hospital just as well as men. In 1917 both Murray and Garrett Anderson were recognized for their accomplishments, but career prospects for women in medicine after the war changed little (World War One at home, n. d, chapter 7).

2.6. Women Workers as Voluntary Aid Detachment (VADs)

Many troops were treated by VADs, short for Voluntary Aid Detachment, or as the troops fondly called them, 'Very Adaptable Dames’ since they did almost every job. They needed to be adaptable, as the casualties were often complicated to nurse and it was very demanding work. An estimated 90,000 VADs attended to the wounded, with most coming from the middle and upper classes (World War One at home, n. d, chapter 7).

There were many famous women who worked as a VAD during the inter war period, Agatha Christie was one of those women. Crime novelist Agatha Christie worked as a VAD in the Red Cross Hospital in Torquay [sic ] Town Hall in Devon. Her role included preparing and

22

dispensing medicines - thus giving her valuable insight into which drugs could be dangerous in the wrong doses. Her first novel, written in 1916, featured a poisoning, and over the course of her writing career she went onto pen the murder of a further 81 victims in this way (World War

One at home, n. d, chapter 7).

2.7. Women's Recruitment in Different Jobs

During WWI (1914-1918), a large number of women were recruited into jobs vacated by men who had gone to fight in the war. This led to women working in areas of work that were formerly reserved for men, for example as railway guards and ticket collectors, buses and tram conductors, postal workers, police, firefighters and as bank ‘tellers’ and clerks. Some women also worked heavy or precision machinery in engineering, led cart horses on farms, and worked in the civil service and factories. However, they received lower wages for doing the same work, and thus began some of the earliest demands for equal pay (Anitha & Pearson, 2013).

The First World War saw a number of changes to rules and regulations of daily life, including the introduction of Britain’s first female police officers. Women campaigners had pushed for the creation of a patrol to tackle widespread fears of prostitution and ‘Khaki Fever’ - young girls succumbing to the lure of men in uniform (World War One at home, n. d, chapter 9).

Two competing organizations were established. The moderate Voluntary Women Patrols were middle class churchgoers who patrolled the capital and saw themselves as aides to the existing police force. The more radical Women’s Police Service was led by former suffragette, Margaret Damer Dawson. Volunteers trained at Little George Street in Westminster in London and by 1917 there were 2,000 women patrolling the country. The first female officer to be given

22

powers of arrest was Edith Smith who was sent to work in Grantham in Lincolnshire. Smith’s report card gives a flavor of her duties: "Forty foolish girls warned, 20 prostitutes sent to other places outside Grantham, two fallen girls helped, five bad women cautioned". But she was highly unusual - the majority of female officers were not granted the power of arrest until 1923. Evelyn Miles was the first woman constable to join Birmingham City Police in 1917, at the age of 50 (World War One at home, n. d, chapter 9).

Former domestic servants became window cleaners, gas fitters and crane drivers. They moved into the munitions factories, where their faces turned yellow and their hair green from the chemicals. They braved explosions and poisonous substances to serve their country – and to earn higher pay (Rowbotham, 2018).

2.8. Urging Women to Study Home Economics

In 1915, the newly formed Women’s Institutes were introduced to Britain from Canada. They urged women to study home economics and aimed to strengthen class harmony. A more radical approach to domestic dislocation was tried in east London. The socialist feminist, Sylvia Pankhurst, who denounced the First World War, put a cost-price restaurant and a mother-and-baby clinic in a former pub, which she renamed The Mother’s Arms. The dangers of being a baby were stressed on all political fronts, an awareness that would lead to the formation of local authority maternity and child welfare committees (Rowbotham, 2018, para. 6).

3. The Political Impact of the First World War on Women of Britain

“The years following World War I brought a big change in politics that made Britain a fully democratic country for the first timeˮ (Burns, 2010, p. 181). The contribution women made